Almost everything that is “positive” about the modern air-travel experience, is positive thanks to Southwest Airlines. Upbeat staff and crew attitude, straightforward rather than hyper-opaque pricing, even the more-or-less egalitarian boarding process—these are all associated with Southwest.

In the past few years, Southwest’s on-time performance has declined to just-average, and in 2018 it had its first-ever fatal accident (in which one person died). Still, when I have the choice—which is to say, when Southwest goes where I want to go—I have a bias toward Southwest.

Two Texans, in 2007. Herb Kelleher at left. (Kevin Lamarque / Reuters)

Two Texans, in 2007. Herb Kelleher at left. (Kevin Lamarque / Reuters)In 1971, when he had just turned 40, Herb Kelleher co-founded Southwest. (And what have you done recently?) In the summer of 1975, when the airline was still getting going — and when I was working, based in Austin, for the then-fledgling Texas Monthly magazine — I did a cover story about Kelleher, his vision for air travel, and the “Great Texas Airline Wars” of that era, which Kelleher’s Southwest ultimately won.

The story, again, is here. If there are things that seem out of date—hey, it was during the Gerald Ford administration, and when I reported and wrote it I was 25.

I really enjoyed knowing Herb Kelleher. He died today, at age 87. RIP—and travel well, in his honor.

One of the odd-but-positive political rumors at the start of this odd year is that Donald Trump is considering former Senator James Webb as a successor to James Mattis as secretary of defense.

Among the reasons why this would be odd:

Webb last held office as a Democrat, and even ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in the 2016 race. Webb is a famously independent-minded character with no ability to suffer fools. (Knowing them both, I can say that Webb is much less willing to go with the organizational flow than Mattis has been.) In his early 40s, he was Ronald Reagan’s secretary of the Navy, but he resigned from that position within less than a year (having worked elsewhere in the Pentagon for several years) because of disagreements with the defense secretary of that era, Frank Carlucci. Webb is a gifted novelist, essayist, and screenwriter, who has returned repeatedly to the self-directed literary life after his periods of public service.Reasons why it would be good news for the country, if it happened:

Webb is smart, tough, and principled. He would instantly become the Cabinet member with most substantive knowledge of his department. He would personify a response to the idea that the United States has become a “chickenhawk nation”—always at war, never willing to deal with the domestic or international consequences of war—and that the current administration itself represents the Chickenhawk Way.Will this happen? I’m betting: No way! Jim Webb is too smart and self-aware to climb into this barrel. But for reading background while the idea is in the air, as a possibility, I offer you:

From 2006, background on an Atlantic cover package that Jim Webb and I wrote together—back in 1980, on the occasion of his running for the Senate as a Democrat; From 2012, what Webb, then at the end of his one term in the Senate, was like on the campaign trail for Democrats; From early 2015, my reaction to news that this person I’d known for many years might run for the Democratic nomination, against Hillary Clinton (and others); From late 2015, after Webb had done poorly with the Democratic electorate, my reaction to news that he might run for president as an independent.As a friend of Webb’s I’d say to him: Are you crazy? Of course you shouldn’t take that kind of responsibility, in this kind of administration.

As a citizen, I’d feel more comfortable if somehow he ended up holding this responsibility in the chain of command. The items above offered as background while we wait to see what happens next

Still Down: New year, new U.S. Congress, new Speaker of the House, same government shutdown. In its first order of business, the House elected Nancy Pelosi as speaker, mostly along party lines (here’s a less often-cited milestone: she’s the first person in more than six decades to reclaim the position).

Now in the majority, House Democrats started the 116th Congress looking to pass a pair of bills aimed at re-opening the government, neither of which offer funding for President Trump’s border wall. The president isn’t conceding: “I’ve never had so much support” for his position on the wall, he said at an impromptu press conference Thursday afternoon. Is there a way to put an end to all government shutdowns, for once and for all? Annie Lowrey has a suggestion.

The Dark Far Side of the Moon: China landed a spacecraft on the far side of the moon—on its own a thrilling feat of engineering. But there’s geopolitical subtext to the achievement, given that national government-supported space exploration began as a patriotism-drenched quest for national power (with a side of scientific discovery).

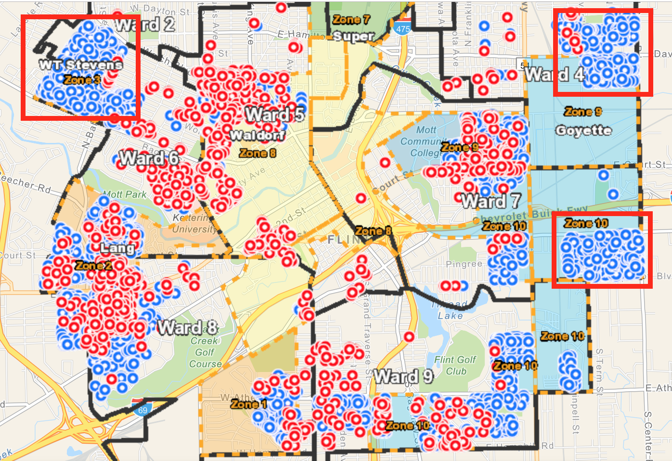

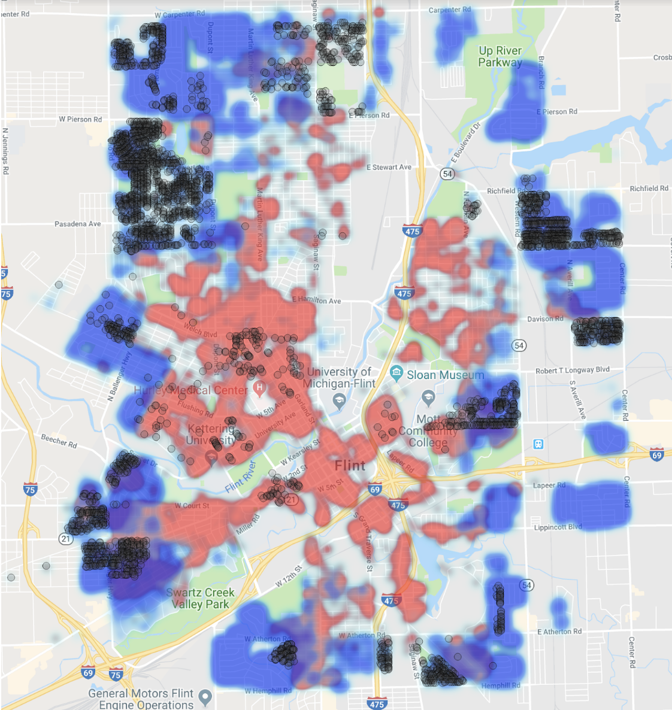

Snapshot A machine-learning model showed promising results in identifying problematic lead pipes in Flint, Michigan, but city officials and their engineering contractor abandoned it. Alexis Madrigal on what went wrong. (Photo: Bill Pugliano / Getty)Let’s Invent a New Holiday

A machine-learning model showed promising results in identifying problematic lead pipes in Flint, Michigan, but city officials and their engineering contractor abandoned it. Alexis Madrigal on what went wrong. (Photo: Bill Pugliano / Getty)Let’s Invent a New HolidayLast month, we asked readers to share some of the unique traditions their families engaged in during the year-end holiday season. The rituals you shared were often quirky and uniformly delightful. They made us think, Why concentrate all these fantastic festivities into one always-too-fleeting month?

With that: We’re in search of a brand new holiday, and we want your help inventing one! National Stress-Bake Day? Turn off the Internet Day? Let us know here by January 11, and come back at the end of the month, when we’ll have you vote for your favorite new holiday.

Evening ReadA “white-sounding” name can significantly impact how a person is treated, including in “hypothetical life-and-death situations,” recent research from two psychologists found:

In one experiment, Zhao and Biernat had participants—about 850 white American citizens recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, which researchers often use to pay subjects small sums in exchange for completing tasks—imagine the famous scenario of the “trolley problem,” in which an out-of-control train is about to run over five people on the tracks; pulling a lever to divert it would save them, but kill a helpless individual on another track. The identities of the five and the one were varied—for instance, the individual was referred to as either an Asian immigrant named Xian, an Asian immigrant named Mark, or a white male named Mark.

As is typical of trolley-problem studies, a majority of subjects said they’d pull the lever, but the names of the individual played a role in the decision. The shares of participants who decided to sacrifice the white Mark and the Asian Mark were about 68 percent and 70 percent, respectively; subjects were more likely to divert the train to hit Xian, which they chose to do 78 percent of the time.

What Do You Know … About Global Affairs?1. This former Boeing executive is now the acting secretary of defense, replacing his outgoing boss Jim Mattis.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. He was sworn in this week as the president of Brazil, making moves on day one to target the rights of minority groups in the country.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. In his first visit to American troops in an overseas combat zone, U.S. President Donald Trump arrived for an unannounced trip late last month to which country?

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: Patrick Shanahan / Jair Bolsonaro / Iraq

Urban DevelopmentsOur partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing city dwellers around the world. Gracie McKenzie shares today’s top stories:

Science has proven that having everyone stand still on the escalator is actually more efficient than allowing space for some people to walk around. Why can’t transit riders be convinced?

Since beginning its subsidized childcare program, Quebec has seen the rate of women in the workforce aged 26 to 44 reach 85 percent, the highest in the world.

Just how apocalyptic is the retail apocalypse? David Montgomery took a closer look at the data and found a more ambiguous picture than the headlines might suggest.

For more updates like these from the urban world, subscribe to CityLab’s Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

It's Thursday, January 3. More than 100 congressional freshmen were sworn in today. Here’s what we were keeping an eye on:

New Speaker: Members of the 116th Congress, the most diverse Congress in America’s history, were sworn in. Nancy Pelosi was elected as speaker—despite a few Democratic defections, many from freshmen representatives—of the now Democrat-controlled House. Most Republican representatives voted for the minority leader Kevin McCarthy.

Making Things Awkward: The partial government shutdown, now in its 13th day, is far from the environment that House Democrats wanted to enter when they regained power. More on the first day of the new Congress below.

Look Over Here: In a rare impromptu White House press briefing, President Donald Trump made a show of not budging on his demands for border-wall funding. He took no questions from reporters.

The Politics of Climate Change: Former Vice President Al Gore rarely wades into the political arena these days, though he does say he thinks the 2020 election will be a “political tipping point” for climate change.

— Madeleine Carlisle and Olivia Paschal

Welcome to the 116th Congress

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi is seated on the House floor. (Carolyn Kaster / AP)

Why the New Democratic Majority Could Work Better Than the Last (Ronald Brownstein)

“As Nancy Pelosi returns to the speakership after the party’s eight-year exile in the minority, she is unlikely to face anything comparable to the systematic resistance she confronted before, from the rural and small-town ‘blue dog’ Democrats trying vainly to hold back a rising Republican tide in their districts.” → Read on.

An Awkward Beginning to Democratic Control of the House (Russell Berman and Elaine Godfrey)

“The shutdown could sap much of the spotlight from the Democrats’ policy agenda, muddling their opportunity to drive the national debate, at least on their own terms, during their first weeks in power. It’s a reminder that this Democratic House majority will be fundamentally different from the one Pelosi led a decade ago.”→ Read on.

The Shutdown is only because of the 2020 Presidential Election. The Democrats know they can’t win based on all of the achievements of “Trump,” so they are going all out on the desperately needed Wall and Border Security - and Presidential Harassment. For them, strictly politics!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 3, 2019President Trump’s New Catchphrase Is an Attempt to Delegitimize Dissent (David Graham)

“It’s that simple phrase, ‘presidential harassment,’ that jumps out.” → Read on.

Trump’s Strange, Fleeting Briefing-Room Cameo (David Graham)

“Backed by several men with clean-shaven heads, Trump stepped to the dais and said ... well, not a great deal.” → Read on.

Al Gore Talks Climate Change and the 2020 Democrats (Edward-Isaac Dovere)

“‘Leaders who advocate solutions to the climate crisis should all run ... I think it’s good for the country and good for the world to have this issue elevated into the top tier during this upcoming campaign.’” → Read on.

How to End Government Shutdowns, Forever (Annie Lowrey)

“There are many paths to ending the shutdown—Trump could sign a funding bill without money for his border wall, say, or with paltry money for his border wall. Better yet, Congress could shut down the government shutdown option, forever.” → Read on.

Trump Just Endorsed the U.S.S.R.’s Invasion of Afghanistan (David Frum)

“It’s amazing enough that any U.S. president would retrospectively endorse the Soviet invasion. What’s even more amazing is that he would do so using the very same falsehoods originally invoked by the Soviets themselves: ‘terrorists’ and ‘bandit elements.’” → Read on.

▪️ How a Feel-Good AI Story Went Wrong in Flint (Alexis Madrigal, The Atlantic)

▪️ Powerless: What It Looks and Sounds Like When a Gas Driller Overruns Your Land (Ken Ward Jr., The Charleston Gazette-Mail; Al Shaw and Mayeta Clark, ProPublica)

▪️ How a Crackdown on MS-13 Caught Up Innocent High School Students (Hannah Dreier, The New York Times Magazine)

▪️ When Death Awaits Deported Asylum Seekers (Kevin Sieff, The Washington Post)

What Else We’re Reading▪️ How Predictable Is Donald Trump? (Isaac Chotiner, The New Yorker)

▪️ Congress’s Incoming Class Is Younger, Bluer, and More Diverse Than Ever (Beatrice Jin, Politico)

▪️ Why Trump’s Generals Have Abandoned Ship (James Stavridis, Time)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily, and will be testing some formats throughout the new year. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

With the government shutdown headed for the two-week mark with no end in sight, President Donald Trump had a succinct message for the press and the nation on Thursday: Please look at me.

All the attention in Washington had been concentrated down Pennsylvania Avenue for the swearing-in of the new Congress, and especially its new Democratic House majority. As my colleagues Russell Berman and Elaine Godfrey noted earlier Thursday, the new group “will share power with a president who does not cede center stage easily.” Like clockwork, Trump decided to show them just what that meant.

Well, like creaky, late clockwork. At 4:07 p.m. eastern time, Press Secretary Sarah Sanders tweeted that there would be a White House briefing at 4:10, three minutes later. The ranks of reporters at the executive mansion were thin—not only was there more action going on in Congress, but no briefing was scheduled, and White House briefings have practically become an endangered species—but those on the spot scrambled to get in place.

[Read: An awkward beginning to Democratic control of the House]

And then they waited, speculating about the reason for the abrupt announcement for the next 20 minutes or so, as 4:10 came and went. Finally, at nearly 4:30, Sanders came onstage, floridly introduced “our very great president, Donald J. Trump,” and got out of the way.

Thus began Trump’s first-ever visit to the briefing room, a milestone he acknowledged in his subsequent remarks. Other presidents have visited more frequently, hosting press conferences there and giving periodic updates to the nation. (Trump eschewed the customary exclamation of surprise at how much smaller the space looks in real life than on TV.) Backed by several men with clean-shaven heads, Trump stepped to the dais and said … well, not a great deal.

He congratulated the speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, on her election, then launched into a set of talking points about the need for a border wall. “I’ve never had so much support than I’ve had in the last week over my stance on border security, for border control, and for, frankly, the wall or the barrier,” he said.

Then he introduced three of the men, who turned out to be Brandon Judd, the president of the National Border Patrol Council and a frequent Trump advocate; Art Del Cueto, a vice president of the NBPC; and Hector Garza, another vice president. Their message: A wall is necessary and important. Del Cueto, a veteran peddler of bunkum, delivered the message most eloquently and most threateningly: “You all got to ask yourself this question: If I come to your home, do you want me to knock on the front door, or do you want me to climb through that window?”

Trump then returned to the lectern, claiming that the men had been at the White House for a long-planned meeting. “It just came at a very opportune time,” he said. “I said, ‘Let’s go out and see the press. You can tell them about the importance of the wall.’” The president whistled past some troubling economic indicators to say that the strong U.S. economy is attracting immigrants (true) and that high-tech tactics couldn’t replace a wall. “I think nobody knows much more about technology, this type of technology certainly, than I do,” he said falsely. “Having drones and various other forms of sensors, they’re all fine, but they are not going to stop the problems that this country has.”

[Read: The real shutdown fight might only be getting started]

Then they were all gone—Trump, Judd, Del Cueto, Garza, and Sanders, without taking a single query from the press. “The point of the briefing room is to take questions!” an anguished reporter shouted as Trump left.

But that’s begging the question, so to speak. If Trump chooses to use the briefing room to serve up reheated talking points to a hastily assembled crew of reporters, that’s the point of the briefing room. From this administration’s perspective, the media are just there to get the president’s attention. That can work: This was truly a remarkable stunt. It was also, however, an entirely superficial one. Trump can attract eyeballs, but that’s unlikely to convince the plurality of the American public who blame him for the shutdown, to grow the small portion who think the wall is an urgent priority, or to bring the shutdown any closer to resolution. Perhaps he’s saving all that for his second briefing-room visit.

Fifty years after humankind first laid eyes on the far side of the moon, a Chinese spacecraft called Chang’e 4 gently touched down and released a rover onto the unexplored terrain Thursday. The far side is incredibly difficult to reach; mission control can’t send radio signals to spacecraft if they’re out of sight. To communicate with Chang’e 4, China put a separate probe in orbit around the moon to relay messages back and forth. Then again, the entire moon is difficult to reach. Space agencies have launched dozens of ambitious missions to Earth’s companion, succeeding miraculously at some times and failing spectacularly at others. After Americans landed on the moon, investment in lunar exploration waned in the United States and Russia. But interest abounds elsewhere, in China, India, and Europe. Humanity has already achieved many lunar firsts, but others are still to come.

Humankind first laid eyes on the far side of the moon in 1968.

“The backside looks like a sand pile my kids have been playing in for a long time,” the astronaut Bill Anders told NASA mission control. For millennia, people had gazed up at the same view of the Earth’s companion—the same craters, cracks, and fissures. As the Apollo spacecraft floated over the unfamiliar lunar surface, Anders described the new territory, which promised to be a tough landing for anyone who tried. “It’s all beat up, no definition,” he said. “Just a lot of bumps and holes.”

Fifty years later, humankind landed in the sand pile.

China set down a spacecraft on the far side of the moon on Wednesday, Beijing time. On Thursday, the spacecraft, named Chang’e 4, after the Chinese goddess of the moon, unlocked a hatch and released a rover onto the lunar soil. The rover carries tools designed to explore the unchartered terrain, which, thanks to a lifetime of facing the cosmos, is covered in craters.

The landing, celebrated already as an achievement for humankind, is a reminder that people can accomplish some wonderfully wild things, given enough curiosity, skill, and rocket fuel. The first photos from the Chang’e 4 mission, captured inside a crater near the moon’s south pole, are chill-inducing. But the landing is also a distinctly geopolitical win for a nation that hadn’t even launched its first satellite when Bill Anders saw that sand pile 50 years ago.

The story of space exploration, the kind carried out by national governments, began as a quest for national achievement and power. In the 1950s, the Americans and the Russians shot rocket after rocket into the sky with patriotism, not discovery, at the forefront of their minds. Any science that came out of it was an added bonus.

[Read: ]China’s growing ambitions in space

Perhaps the clearest illustration of this geopolitical drive is a Soviet spacecraft called Luna 2. The Soviet Union launched Luna 2 in 1959, two years after sending the first satellite into orbit around Earth. Luna 2 was beachball-shaped, with spiky antennas, and weighed 390 pounds. The spacecraft carried multiple instruments designed to measure the radiation environment around the moon. It transmitted this data back to Earth as it flew through space. When Luna 2 approached the lunar surface, mission control held their breath.

The signals stopped. Luna 2 had slammed into the moon, breaking apart into pieces.

Mission control erupted in cheers. For the Soviet Union, it didn’t matter that Luna 2, which became the first spacecraft to reach the moon, had been smashed into smithereens. The point was to get there first—to mark territory. The Soviets had packed the spacecraft with metal pendants bearing the hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union. The impact scattered them across the lunar regolith, where they remain today, as if on display at a museum.

For the United States and the Soviet Union, every milestone in the space race was commemorated as an achievement for all humankind, yes, but also as a gain for the nation—for its government, its policies, its ideals—that reached it first. Two days after Luna 2 completed its mission, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev visited the United States. As the British historian Robert Cavendish wrote in the magazine History Today, Americans suspected that the space mission had been coordinated with the political visit: Khrushchev was “beaming with rumbustious pride” and gleefully “lectured Americans on the virtues of communism and the immorality of scantily clothed chorus girls.”

A decade later, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon, the Soviets were decidedly less rumbustious. Sergei Khrushchev, the son of the premier, told Scientific American in 2009 that Soviet propaganda let the news of “one giant leap for mankind” slide by without much fanfare. “It was not secret, but it was not shown to the public,” he said.

By then, China had already been trying to insert itself into the space race for more than a decade. After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, Mao Zedong instructed his country’s scientists and engineers to prepare a satellite of their own, to launch in 1959, in honor of the Great Leap Forward, the leader’s ultimately failed plan for rapid industrialization. The directive from the top to scientists was simple: “Get it up, follow it around, make it seen, make it heard.”

But the country didn’t have the necessary technology for such a fast turnaround, and space-exploration efforts would be repeatedly derailed by political turmoil in the coming decades. The satellite launched at last in 1970, equipped with a single purpose: playing the first few bars of “The East Is Red,” an instrumental song glorifying China’s Cultural Revolution.

In recent years, though, China’s space efforts have jumped to warp speed. When the country launched its first astronaut in 2003, it became one of only three countries to have done so. It sent an uncrewed orbiter around the moon in 2007, and a rover in 2013. In 2011, it launched a space station that astronauts visited twice before it was decommissioned and deliberately crashed into the Pacific Ocean. A second space station launched in 2016. In 2018, China launched more rockets into orbit than any other country.

[Read: ]Why it’s a bad idea to launch rockets over land

China has more bold plans for the future. The country is aiming to land a rover on Mars in early 2021 and, if successful, would become the second country after the United States to accomplish the feat. It also wants to land astronauts on the moon by 2030.

These and other milestones can be celebrated on a global scale as an achievement for the human species, just like the landing was. “It is human nature to explore the unknown world,” Wu Weiren, the chief designer of the Chang’e 4 mission, said in a television interview, according to The New York Times. “And it is what our generation and the next generation are supposed to do.”

But China’s space accomplishments are as symbolic and strategic as the Apollo and Vostok programs were in the 1960s, especially now, when space agencies in Europe, Russia, India, and, most recently, the United States have put a big focus on lunar exploration. “We are building China into a space giant,” Wu said.

For spacefaring nations, impressive feats, whether it’s landing on Mars or on the far side of the moon, will always be seen through the lens of the nation that managed to pull it off. “When you are the first country to land a probe on the far side of the moon, that says something about your science and technology, that says something about your industry,” the Heritage Foundation’s Dean Cheng, one of the few Chinese-speaking analysts in the United States that focus on China’s space program, told The Atlantic in 2017.

If it still seems silly to consider geopolitical history in the exuberant moments after a moon landing, consider this reaction from the Global Times, a newspaper run by the Communist Party, China’s ruling party, reported by The Washington Post:

Unlike mankind’s mania in the past, the Chinese people ultimately harbor the dream of shared human destiny and practices open cooperation. We choose to go to the back of the moon not because of the unique glory it brings, but because this difficult step of destiny is also a forward step for human civilization!

A “forward step for human civilization,” indeed. But the “unique glory” is certainly nice, too.

When the Trump administration released its school-safety report last month, it landed with a thud—and only partly because it’s a clunky 180 pages. Many of the recommendations in the report, authored by the Federal Commission on School Safety, are aimed at fostering a better school climate—how a school feels to the students who attend it—whether that’s through improved access to counseling and mental-health services or a greater emphasis on social-emotional learning. But other recommendations were met with derision, such as a proposal to rescind an Obama-era rule urging schools to be mindful of whether they might be punishing minority students at a higher rate than white students.

Study after study has shown that black students are unevenly suspended or expelled from schools nationwide. The 2014 school-discipline guideline was the Obama administration’s attempt to remedy that. The Trump commission, however, argued that deciding how students should be disciplined should not be the federal government’s job, but the teachers’. Both administrations, at least, agreed that discipline was also a matter of school climate—something educational leaders have been trying desperately to improve.

[Read: How school suspensions push black students behind]

A new study by the Rand Corporation, a nonpartisan think tank, shows just how crucial improving the climate at school can be to helping decrease suspensions. In 2013, Pittsburgh’s public schools were trying to figure out how to remedy racial disparities in discipline. At the time, they had mandatory diversity training for staff that sought to address implicit bias and discrimination in the classroom, but they wanted to do more. Restorative practices, which are nonpunitive ways of responding to conflicts, had been gaining momentum among school leaders as a way to help curb suspensions.

So the district got a grant to try out restorative practices in their schools, randomly selecting 22 of them to receive the restorative treatment, while 22 others went about business as usual. The basic goal of restorative practices is to build relationships between teachers and students, so that students will be less likely to act out. Teachers start off the school year by asking students innocuous questions such as what the students did that summer. As the year goes on, the questions grow more personal and introspective, and students build trust with the adults and classmates around them. Of course, formal times for such events can be time-consuming, so it is often recommended that the practices are woven into the day. As much as restorative practices aim to change how students are disciplined, they also seek to change the behavior that might require discipline, improving the overall climate of the school.

[Read: One Ohio school’s quest to rethink bad behavior]

The researchers examined the schools—elementary, middle, and high schools—over two years and found that restorative practices greatly reduced the number of school days lost to suspension, particularly among elementary schoolers. The dip was most acute among black, low-income, and female students, and nonviolent offenses drove the decline. “It seems to be the case that restorative practices were providing an alternative that the staff felt they could use to enforce discipline, [especially] for offenses that weren’t extremely serious in the sense of endangering people’s safety,” John Engberg, a researcher at Rand, told me.

On top of that, the report found no negative impact on the test scores of students in the schools that had restorative treatments. “That seems to indicate that keeping kids in school is not leading to a deteriorating learning environment,” Engberg said. And, for their part, teachers who worked at schools with the restorative treatments rated their climate as comparatively more positive.

There were some things that restorative practices couldn’t change, though. Sure, academic outcomes, such as test scores, didn’t drop, but they didn’t improve either. The decline in suspension rates was most stark for elementary-school students rather than middle- or high-school students, where the effects were more muted, suggesting that early intervention is important.

Changing a school’s climate is a long process, Catherine Augustine, a senior researcher at Rand, told me.“This isn’t Let’s go to a one-day workshop and we’ll all be restorative,” she said. It takes work from teachers, faculty, staff, and students. And the researchers themselves still have a lot of work to do in terms of understanding how restorative practices work and whether the gains made by the elementary schoolers will carry forward through middle and high school. Still, the bipartisan goal of improving school climate may not be as elusive as it seems.

Donald Trump is a devoted sloganeer, from “You’re fired” to “Make America great again.” But slogans grow tired and lose their oomph with time and repetition, which means it’s important to keep refreshing and replacing them.

Enter “presidential harassment.”

On Thursday, with the government shutdown in its 13th day, with no sign of abating, and the new Democratic majority taking over the House, the president tweeted this:

The Shutdown is only because of the 2020 Presidential Election. The Democrats know they can’t win based on all of the achievements of “Trump,” so they are going all out on the desperately needed Wall and Border Security - and Presidential Harassment. For them, strictly politics!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 3, 2019There is, as they say, a lot going on here. Trump is probably not wrong to suggest a 2020 connection. Democrats are staunchly opposed to the wall as a waste of money, but they also want to deprive him of a victory on a key campaign promise, undermining his reelection hopes. (There’s a lot of politics in this shutdown fight for Trump, too, of course—he was signaling a willingness to compromise until he was assailed by right-wing media figures.) And who knows what the scare quotes around Trump’s name are meant to be? (Maybe there’s a weird Dave-style switch just waiting to be discovered?)

[Read: Trump started 2019 on an angry, lonely note]

But it’s that simple phrase, “presidential harassment,” that jumps out. This is the eighth time he’s employed it, according to factba.se, with uses coming more frequently of late. The nascent rise of the phrase is an indication that Trump feels newly embattled, but it also underscores the way he tries to construe any criticism of himself as illegitimate.

Trump is a magpie, borrowing his most famous lines: “Make America great again” from Ronald Reagan; “America first” from Charles Lindbergh; “fake news” from Hillary Clinton. He nicked “presidential harassment” from Senator Mitch McConnell. The Senate majority leader seems to have coined the phrase in an October 10 Associated Press interview, and then reprised it the day after the midterm election, warning Democrats against prying too deeply into Trump’s affairs.

“The whole issue of presidential harassment is interesting,” McConnell said. “I remember when we tried it in the late ’90s. We impeached President Clinton. His numbers went up and ours went down and we underperformed in the next election.”

Leaving aside whether McConnell offered this advice in good faith, he meant it in a limited sense of oversight investigations. Trump, displaying his knack for branding, has quickly expanded the phrase to encompass any kind of criticism. First came this tweet, five days after McConnell’s post-election warning, and seeming to follow the same definition:

The prospect of Presidential Harassment by the Dems is causing the Stock Market big headaches!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 12, 2018Two days later, in an interview with The Daily Caller, Trump said:

I think we’ll do very well if they want to play the presidential harassment game. If they play the presidential harassment game I don’t think anything’s going to be done ’cause why would I do that, okay? If they want to get things done I think it will be fantastic, I think we can get a lot done.

Three days after that, he used it again during a gaggle, this time in a riff about the presumptive Democratic House leader, who was then fending off a leadership challenge:

I like Nancy Pelosi. I mean, she’s tough and she’s smart. But she deserves to be speaker. And now they’re playing games with her just like they’ll be playing with me with—it’s called “presidential harassment.” The president of your country is doing a great job, but he’s being harassed. It’s presidential harassment.

In addition to the odd dip into the third person, this represents an important step in Trump’s process for reifying his claims, with “it’s called” serving a purpose similar to “many people are saying,” when in fact only he is saying it, or the one calling it that. Already, the meaning is slipping—opposing Pelosi is harassment, just as opposing Trump constitutes harassment. See, for example, this December 6 invocation:

Without the phony Russia Witch Hunt, and with all that we have accomplished in the last almost two years (Tax & Regulation Cuts, Judge’s, Military, Vets, etc.) my approval rating would be at 75% rather than the 50% just reported by Rasmussen. It’s called Presidential Harassment!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 6, 2018On December 23, he complained on Twitter, “Presidential Harassment has been with me from the beginning!” Two days later, during a videoconference with members of the military, Trump couldn’t resist turning the occasion into a political rally. Asked about what to expect in the new Congress, he answered, “Well, then probably presidential harassment, and we know how to handle that. I think I handle that better than anybody. There’s been no collusion.”

On December 29, in the midst of a long string of self-pitying messages, he tweeted:

I am in the White House waiting for the Democrats to come on over and make a deal on Border Security. From what I hear, they are spending so much time on Presidential Harassment that they have little time left for things like stopping crime and our military!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 29, 2018Every president hates criticism, though few take it as personally or respond as prolifically as Trump does. More important, few if any have dedicated themselves so fiercely to portraying any criticism of themselves as illegitimate per se. By spinning House oversight (a constitutionally mandated function) and any other criticism as “harassment,” he labels it untoward, unseemly, even potentially illegal.

[Read: The most striking thing about Trump’s mockery of Christine Blasey Ford]

Labeling dissent as illegitimate is uncomfortable in a liberal democracy, a form of government about which Trump is ambivalent at best. And his victimhood is unearned. There’s more than enough evidence to warrant stricter congressional oversight of the executive branch. Could Democrats overreach? Of course. But it’s too soon to know. Trump is trying to preempt them.

The phrase is uncomfortable for another reason, too. It’s difficult, especially in this age, to decouple the word harassment from its frequent prefix of sexual. That’s perhaps especially true for Trump. In addition to the at least 19 women who have publicly accused the president of sexual misconduct, there is the Access Hollywood tape in which Trump boasts about sexually assaulting women because he’s a star. He also mocked Christine Blasey Ford, who accused Justice Brett Kavanaugh of attempting to rape her in high school.

By commandeering the term harassment to dismiss any criticism of himself, Trump is also belittling his own accusers. The White House has flatly rejected all the accusations against the president and refused to recognize them. With his woe-is-me claims of “presidential harassment,” Trump is challenging the public to do the same to him.

Late in 2018, The Atlantic’s Family section asked readers to share some of the unique traditions their families engaged in during the year-end holiday season. The rituals you all shared with us were often quirky (one of them involved a Speedo-clad George Michael made of marzipan) and uniformly delightful. And they made us think: Why concentrate all these fantastic festivities into one always-too-fleeting month? What about the rest of the year? Couldn’t those other periods stand to be a little more joyful, or a little more meaningful, or a little more fun?

With that in mind: We’re in search of a new holiday. And we’re hoping for your help in creating it. Maybe, for example, there should be, sometime in the dark days of winter, a National Stress-Bake Day. Or maybe February would be a little more festive were Galentine’s Day to be converted from a sitcomic treasure into a more broadly celebrated holiday. A beloved local tradition that deserves more widespread recognition? Weird Family Stories Day? Get Back in Touch Day? Resolution Revision Day? Turn Off the Internet Day? (All of the internet, that is, except for TheAtlantic.com and its subsidiaries?)

If you have an idea for a holiday that does not currently exist but should very definitely exist, please let us know by filling out this form by January 11. We’ll put together the ideas you send us and then, later in the month, ask you to vote on them—in a face-off we hope will end with a new holiday that, should you choose to celebrate it, will bring merriment, meaning, or, at the very least, another excuse to consume seasonally justified baked goods.

Here’s a sample, courtesy of the Atlantic staff writer and holiday enthusiast Megan Garber:

What’s the name of the holiday you’d like to bring into existence?

Nocrastination Week

How would you celebrate it? Please describe the festivities, in a paragraph:

If you are a human person currently living in this hectic world, there is a very good chance that you have a bunch of tasks, big and absurdly small, that you’ve been meaning to do for days (or weeks! or months! OR YEARS?) … and have been putting off. Well, this is the week to stop putting them off: spring cleaning, essentially, but with a broader mandate and a specific deadline. This, to be clear, is not at all a glamorous holiday—but what Nocrastination Week lacks in flair, it makes up for in practicality. It’s a holiday that allows its celebrants to give themselves the ultimate gift: the relief that comes with marking those haunting To-Dos as, finally, Done.

When do you imagine it would fall on the calendar? Will it be celebrated on a specific date—or a specific week, or specific day of the week?

Nocrastination Week should probably fall during the late winter, sometime in February or early March. It lasts the week to allow for maximum flexibility with participants’ schedules. Its final day—which is also its final deadline—will be a Sunday. If you don’t get your set task accomplished by sundown that Sunday, you will not, sadly, get any Nocrastination Cake (see below).

Are there any particular foods, costumes, decorations, songs, or anything else along those lines that are associated with the holiday? If so, please describe them:

Yes, there’s a food! Nocrastination Cake: consumed after the day’s task is complete, as a reward for getting the job done.

Why should this holiday exist?

Nocrastination Week is an antidote to the pressures and expectations of the December holidays. It’s not about acquiring things; it’s about doing away with things that are sources of stress. Like any good holiday, it’s a celebration of stuff that, ideally, people would be practicing throughout the year. But it also acknowledges the obvious: There’s nothing like a deadline.

Updated on January 3 at 10:20 p.m. ET

This was not how Democrats expected, much less hoped, to begin their new House majority.

After the blue wave crested, ever so slowly, in November, the start of the 116th Congress on Thursday loomed as a moment of potential drama, a constitutionally mandated deadline for the party to decide whether to make a generational change in leadership. In the weeks after the election, Nancy Pelosi scrambled to put down an intraparty rebellion that threatened to turn her elevation to a second stint as speaker into a nail-biting vote and a showcase of Democratic division. She succeeded in impressive fashion, securing support vote by vote and demonstrating the formidable skills that have kept her atop the Democratic caucus for 16 years.

Once that leadership challenge fizzled, a new, more triumphant vision for the opening of Congress emerged: Pelosi would become the first person in more than 60 years to reclaim the speaker’s gavel, and then Democrats would promptly set about passing bills to deliver on their campaign promises and place their first checks on President Donald Trump’s power. Their initial volleys would include legislation to enact so-called democracy reforms to address campaign-finance loopholes, and measures to expand voting rights and limit gerrymandering. Bills to beef up protections for people with preexisting conditions in the Affordable Care Act and tackle high prescription-drug prices would follow soon after. Yes, these proposals would be dead-on-arrival in the Republican-controlled Senate, but the goal was to send an immediate message to their constituents and reset a legislative debate that had swung far to the right for the past two years.

Instead, neither of those scenarios occurred.

Pelosi won the speakership in a floor vote early Thursday afternoon, having punctured a group of about two dozen Democratic opponents by cutting one-off deals with some members and agreeing to procedural reforms to secure the support of another bloc. She nabbed 220 votes, narrowly clearing the majority she needed after 15 House Democrats either stated the names of other candidates or voted present.

Democrats inside the Capitol were jubilant as they gathered on the House floor with their families for the formal swearing-in and speaker vote. But they won’t be able to fully celebrate their first House majority in eight years, nor will they be able to swiftly act on their agenda. They’re taking over in the midst of a partial government shutdown—the first time in the 42-year history of the modern budget process that a transfer of power in Congress has taken place while major parts of the federal bureaucracy are shuttered due to a lapse in funding.

Within hours of gaveling in the new Congress, House Democrats passed two bills aimed at reopening the government, including one that’s identical to legislation the Senate unanimously approved in December to extend funding for the Department of Homeland Security through February 8. The other measure included bipartisan, full-year appropriations bills for eight other federal departments. Both cleared the House with some bipartisan support, as a handful of Republicans broke with their leadership to vote yes.

The move to pass substantive votes so quickly after members took the oath of office was unusual. “It just drives home how important the work is that we have to do here,” said Representative Katie Porter of California, “and the fact that we’re starting it tonight, that we’re canceling celebrations and parties to do the work the American people have sent us here to do.”

Neither bill included additional funding for Trump’s border wall, as he’s demanded. The bills represented an opening salvo both at Trump and at the Republicans who run the Senate, a bid to showcase Democrats’ new leverage while pressuring the GOP to end a shutdown the president had said he’d be proud to own.

Indeed, as the new Congress begins, there is no end in sight to the shutdown. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said he would ignore the bills that House Democrats advanced—as well as any legislation that does not have the explicit support of the president. McConnell acknowledged after a White House meeting on Wednesday that parts of the government could remain closed for weeks longer.

The stalemate won’t stop Democrats from moving on the rest of their agenda. Pelosi’s office announced an event for Friday to unveil the party’s democracy-reform legislation, with votes next week. Nor did it interrupt the traditional pomp and circumstance that accompanies the biannual convening of Congress, which proceeded with only glancing references to the government shutdown.

Lawmakers new and old gathered in the House chamber shortly after noon, and the portrait of the 116th Congress was a study in contrasts: The larger Democratic side of the aisle comprised the most diverse House caucus in the nation’s history—spanning race, ethnicity, gender, even styles of clothing—while the Republicans were a sea of overwhelmingly white men in dark suits. The members’ first act is always the roll-call vote for speaker, wherein each lawmaker calls out the name of their preferred candidate.

Representative Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the chairman of the Democratic caucus, brought his party to its feet with an energetic nominating speech for Pelosi. “Let me be clear: House Democrats are down with NDP—Nancy D’Alesandro Pelosi!” he shouted to laughs and cheers. Representative Liz Cheney of Wyoming, the daughter of the former vice president who was recently elevated to the fourth-ranking GOP post, nominated Representative Kevin McCarthy of California with a speech that reiterated the party’s full support for Trump’s bid to “build the wall.”

The vote for Pelosi was without much drama but not without defections. Many of the 15 members who withheld their support were freshmen who had pledged to voters that they would not back Pelosi for speaker. Four of them voted instead for Representative Cheri Bustos of Illinois, a fourth-term Democrat who will head the party’s campaign committee for the next two years. Representative Anthony Brindisi of New York voted for former Vice President Joe Biden—the speaker technically does not have to be a member of the House—while two House Democrats voted for Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, despite the fact that she serves in the Senate.

McCarthy suffered losses on the Republican side as well. Four votes went to Representative Jim Jordan of Ohio, the Freedom Caucus leader who had challenged McCarthy for the top GOP post.

In her first speech to the House, Pelosi mixed paeans to bipartisan comity with a recommitment to Democratic policy priorities. “I pledge that this Congress will be transparent, bipartisan, and unifying; that we will seek to reach across the aisle in this chamber and across the divisions in this great nation,” she said.

Pelosi never mentioned Trump by name, but the only two presidents she cited were Republicans: Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. The new speaker quoted a Reagan tribute to America’s history as a nation of immigrants, and when Republican members of the House didn’t clap, she admonished them. “You won’t applaud for Ronald Reagan?” she asked, in a rare departure from her scripted remarks.

Turning to the Democratic agenda, the new speaker called for action to address income inequality and the climate crisis, to protect Dreamers and combat gun violence, and to reinvest in public education and workforce development. “Working together, we will redeem the promise of the American dream for every family, advancing progress for every community,” she said.

But the shutdown could sap much of the spotlight from the Democrats’ policy agenda, muddling their opportunity to drive the national debate, at least on their own terms, during their first weeks in power. The rancor associated with the funding impasse was also dispiriting to new lawmakers who had hoped that their arrival in Washington would mean a fresh start. “It’s obviously not ideal because there are many of us who came here to try to act in a bipartisan fashion, to try to form coalitions, to try to get things done,” said Representative Colin Allred, a freshman Democrat from Texas. “And this is a very bad start.”

It’s also a reminder that this Democratic House majority will be fundamentally different from the one Pelosi led a decade ago. This freshman class may be infused with the new energy of young, diverse progressives and a record number of women. But it will share power with a president who does not cede center stage easily.

Orchestrating this shutdown may not help Trump broaden his appeal at the midpoint of his term. But if nothing else, it will deny Pelosi, and the new House majority she leads, their full moment of triumph.

“As a foreigner in the U.S., since the first day I arrived,” says Xian Zhao, “I have been constantly asking myself this question: Should I adopt an Anglo name?”

Zhao, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto, says that his cousin and his aunt changed their name from Pengyuan and Guiqing to Jason and Susan, respectively, upon moving to the U.S. Some of his grad-school peers made similar decisions, but after some deliberation while completing his Ph.D. in the U.S., he resolved to continue using his given first name, which means “significant” and “outstanding.” “Hearing people calling me Alex or Daniel doesn’t mean anything to me,” he told me.

The dilemma, though, inspired Zhao to study first names in an academic capacity, which he’s done with Monica Biernat, a psychology professor at the University of Kansas who was his Ph.D. advisor. Most recently, they looked at the relationship between someone’s first name and whether people would offer them help in “hypothetical life-and-death situations.”

[Read: Why don’t parents name their daughters Mary anymore?]

In one experiment, Zhao and Biernat had participants—about 850 white American citizens recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, which researchers often use to pay subjects small sums in exchange for completing tasks—imagine the famous scenario of the “trolley problem,” in which an out-of-control train is about to run over five people on the tracks; pulling a lever to divert it would save them, but kill a helpless individual on another track. The identities of the five and the one were varied—for instance, the individual was referred to as either an Asian immigrant named Xian, an Asian immigrant named Mark, or a white male named Mark.

As is typical of trolley-problem studies, a majority of subjects said they’d pull the lever, but the name of the individual played a role in the decision. The shares of participants who decided to sacrifice the white Mark and the Asian Mark were about 68 percent and 70 percent, respectively; subjects were more likely to divert the train to hit Xian, which they chose to do 78 percent of the time.

Of course, there are limits to hypothetical ethical dilemmas (and to research conducted using Mechanical Turk), but these effects appear in the real world too. In previous research, Zhao and Biernat found that white professors were more likely to respond to an emailed request from a Chinese student when the student went by Alex, as opposed to Xian. And a separate paper found that Chinese job seekers received more favorable responses from employers when they went by anglicized names. (Other research has noted similar difficulties that arise for black job applicants.)

A lot of research on immigration and names examines the subject from an economic perspective. A 2016 paper in the American Sociological Review looked at the first names given to the generation that came after the wave of immigration to the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. “Native-born sons of Irish, Italian, German, and Polish immigrant fathers who were given very ethnic names ended up in occupations that earned, on average, $50 to $100 less per year than sons who were given very ‘American’ names,” the researchers wrote. “This represented 2 to 5 percent of annual earnings.” (They determined the “ethnic-ness” or “American-ness” of a name based on how frequently it was given in each immigrant and native-born population at the time.)

Some of this effect, the researchers estimated, was due to class differences among parents (which remain a strong determinant of a child’s future job prospects), but most of it had to do with the symbolism of the name itself. Interestingly, the economic advantage that came with having a “more American” name still applied to people with surnames that clearly indicated their parents’ foreign origins. The researchers surmised that American-sounding first names, then, functioned more as a signal of “an effort to assimilate” than a means of “hiding one’s origins.”

Immigrants in that era frequently felt pressured to change their own first name. A separate study, also from 2016, found that “at any given time between 1900 and 1930,” about 77 percent of immigrants had an American-sounding first name, and it was the norm for them to have dropped their original name within a year of entering the U.S. There were economic overtones here too: Male immigrants were more likely to change their name if they lived in counties where other immigrants had trouble getting jobs.

Researchers in other countries, such as Germany and Sweden, have also used first names as a proxy for assimilation, and picked up on similar economic consequences. Three researchers in Europe estimated that in France, between 2003 and 2007, there would have been more than 50 percent more babies born with an Arabic name if there weren’t an economic penalty associated with having one.

There seems to be a pattern when it comes to immigrants’ decision to give their children “American-sounding” (which in this context, as in many others, is a sort of code for “whiter-sounding”) names. In 2009, the New York University sociologist Guillermina Jasso told The New York Times that “in general, the names immigrants give their children go through three stages—from names in the original language, to universal names, and finally to names in the destination-country language.” The reporter observed that as the proportion of Hispanic Americans who were born in the U.S. increased, the name José seemed to be declining in popularity.

But perhaps when discrimination against a certain ethnic group diminishes, there is an opportunity for a naming reversal. Historically, many Jews have changed their surnames—Larry King’s last name was originally Zeiger, and Jon Stewart’s was Leibowitz—but today, some are changing theirs to something more Jewish. In a 2014 article on shifting naming conventions, the Israeli newspaper Haaretz mentioned two American Jews who had, in an effort to honor their roots, changed their last names from Bush to Silberbusch and Reed to Safran. So maybe there’s a fourth stage: Once immigrant groups establish themselves in new countries, they feel they have room to celebrate the people who helped bring them to where they are now.

It was only one moment in a 90-minute stream of madness.

President Donald Trump convened a Cabinet meeting, at which he invited all its members to praise him for his stance on the border wall and the government shutdown. There’s always a lively competition to see which member of the Cabinet can grovel most abjectly. The newcomer Matthew Whitaker may be only the acting attorney general, but despite—or perhaps because of—that tentative status, he delivered one of the strongest entries, saluting the president for sacrificing his Christmas and New Year’s holiday for the public good, and contrasting that to members of Congress who had left Washington during the Trump-created crisis.

But that was not the crazy part.

The crazy part came during the president’s monologue defending his decision to withdraw all 2,000 U.S. troops from Syria and 7,000 from Afghanistan, about half the force in that country.

[David Frum: The crisis facing America]

“Russia used to be the Soviet Union,” he said.

Afghanistan made it Russia, because they went bankrupt fighting in Afghanistan. Russia … the reason Russia was in Afghanistan was because terrorists were going into Russia. They were right to be there. The problem is, it was a tough fight. And literally they went bankrupt; they went into being called Russia again, as opposed to the Soviet Union. You know, a lot of these places you’re reading about now are no longer part of Russia, because of Afghanistan.

Let’s go to the replay:

The reason Russia was in Afghanistan was because terrorists were going into Russia. They were right to be there.

To appreciate the shock value of Trump’s words, it’s necessary to dust off some Cold War history. Those of us who grew up in the last phases of the Cold War used to know it all by heart, but I admit I had to do a little Googling to refresh my faded memories.

Through the 1970s, Afghanistan had been governed by a president who was friendly to the Soviet Union, but it was not reliably under Soviet control. That president, Mohammad Daoud Khan, became convinced that the local Communists were plotting against him. He struck first, assassinating one Communist leader in April 1978, and arresting others.

Instead of preventing the plot, this coup-from-above triggered it. In April 1978, the Communists—enabled by their strong presence in Afghanistan’s Soviet-trained military—seized power.

The new regime launched an ambitious modernizing agenda: women’s rights, land reform, secularization. That project went about as well as expected. While the Communists appealed to a small, educated elite in Kabul, they offended the ultraconservative countryside. Violent guerrilla resistance gathered. The guerrillas called themselves “mujahideen,” holy warriors. The Kabul government dismissed them as “bandit elements” and “terrorists.”

[Read: What Putin really wants]

By the end of 1979, the Kabul-based Communist government was teetering, nearing collapse. The Soviet authorities in Moscow blamed the incompetence, corruption, and internecine violence of their local allies. In December 1979, they overthrew and killed the then-Communist leader, installed somebody more compliant, and deployed 85,000 troops to enforce their rule over the countryside. The Soviets had expected a brief, decisive intervention like those in Prague in 1968 or Budapest in 1956. Instead, the war turned into a grinding Vietnam-in-reverse. The Soviets withdrew, defeated, in 1989.

Here’s why Trump’s lopsided view of this story is so telling. Inflicting that defeat on the U.S.S.R. was a major bipartisan foreign-policy priority of the 1980s. The policy was designed by Jimmy Carter’s national-security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and executed by the Reagan administration.

It’s amazing enough that any U.S. president would retrospectively endorse the Soviet invasion. What’s even more amazing is that he would do so using the very same falsehoods originally invoked by the Soviets themselves: “terrorists” and “bandit elements.”

It has been an important ideological project of the Putin regime to rehabilitate and justify the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. Putin does not care so much about Afghanistan, but he cares a lot about the image of the U.S.S.R. In 2005, Putin described the collapse of the Soviet Union as (depending on your preferred translation) “the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the 20th century” or “a major geopolitical disaster of the 20th century”—but clearly a thing very much to be regretted.

The war in Afghanistan helped bring about that collapse, not because it bankrupted the Soviet regime—that was an effect of the break in the price of oil after 1985—but because it forced a reckoning between the Soviet regime and Soviet society. As casualties mounted, as soldiers returned home addicted to heroin, Soviet citizens began demanding the right to speak the truth, not only about the war in Afghanistan, but about all Soviet reality.

It’s fitting that Putin’s campaign to reimpose official lying would culminate in a glorification of the catastrophic Afghanistan war. And clearly, that campaign has swayed the mind of the president of the United States.

As of mid-morning on January 3, the day after the president’s repetition of Soviet-Putinist propaganda in the Cabinet room, there has been no attempt by the White House to tidy things up: no presidential tweet, no corrective statement. The president’s usual defenders—Sean Hannity, Fox & Friends, the anti-anti-Trump Twitter chorus—have likewise ignored the whole matter. They’re back to denouncing the Steele dossier, fulminating against Mueller, and reprising the Clinton-email drama. There’s apparently nothing they can think of to say in exoneration or excuse.

Putin-style glorification of the Soviet regime is entering the mind of the president, inspiring his words and—who knows—perhaps shaping his actions. How that propaganda is reaching him—by which channels, via which persons—seems an important if not urgent question. But maybe what happened yesterday does not raise questions. Maybe it inadvertently reveals answers.

The new Democratic majority that takes command of the House on Thursday starts with 21 fewer seats than the party held the last time it elected Nancy Pelosi as speaker. But this new majority may prove easier for the party to both manage legislatively and defend electorally.

Though slightly smaller, the Democratic caucus that’s assuming power is far more ideologically and geographically cohesive than the party’s previous majority 10 years ago. While the 2009 class included a large number of Democrats from blue-collar, culturally conservative, rural seats that were politically trending away from the party, the new majority revolves around white-collar and racially diverse urban and suburban districts that are trending toward it.

That won’t eliminate all internal disagreements inside the caucus, particularly as an energized progressive block moves to flex its muscles. But it does mean that as Pelosi returns to the speakership after the party’s eight-year exile in the minority, she is unlikely to face anything comparable to the systematic resistance she confronted before, from the rural and small-town “blue dog” Democrats trying vainly to hold back a rising Republican tide in their districts.

That resistance shadowed every item on the Democratic agenda during former President Barack Obama’s first two years, from health care to climate change. “Nothing was easy,” says Henry Waxman, the veteran former legislator who served as chairman of the powerful House Energy and Commerce Committee over that period. “I remember complaining to Pelosi that she was putting too many blue dogs on the committee and she said, ‘You’ll have to do what we all have to do: compromise.’”

[Steve Israel: Nancy Pelosi is the speaker Democrats need]

Compromise was necessary back then because the party still relied on blue dogs to keep its control of the House, though their districts were increasingly attracted to Republicans in presidential elections. CityLab has developed an innovative system for ranking House districts on an urban-rural scale based on the density of their population and other factors. Its analysis found that, in 2009, fully 89 of all House Democrats, or 35 percent, held seats in the two most rural categories. My own previous analysis of the 2009 class found that 76 Democrats represented heavily blue-collar seats that had fewer minorities and fewer white college graduates than the national average.

The moderate-to-conservative blue dogs centered in those rural and blue-collar seats were a consistent source of unease about the aggressive agenda Democrats pursued with unified control of the White House, Senate, and House under Obama. In 2009, 44 Democrats voted against the cap-and-trade climate-change bill that Waxman and Pelosi steered through the House; the next year, 34 voted against final passage of the Affordable Care Act. (“I thought that [cap-and-trade] was difficult but health care would be easy,” recalls Waxman, who shepherded both bills through his committee. “But even health care wasn’t easy.”) After those two votes, the blue dogs’ reluctance to take more risky votes helped convince Pelosi and the White House to abandon consideration of comprehensive immigration reform, much less any new gun-control measures.

That caution couldn’t stem the tide. The rural and blue-dog Democrats were living on borrowed time as small-town, evangelical Christian, and blue-collar whites were becoming more reliably Republican. In the 2010 midterm election, the GOP hunted the blue dogs nearly to extinction: Fifty-one of the 89 rural Democrats CityLab identified were defeated as the GOP surged into the majority.

Critically, the Democrats rebuilt their majority in 2018 without relying on such inherently unstable turf. Instead, the new class has the party advancing into different terrain. Only 35 Democrats in the new caucus hold seats in CityLab’s two most rural categories, according to figures shared by David Montgomery, who developed the ranking system. That represents only about one-fifth of all of those seats—and just 15 percent of the total Democratic caucus. By contrast, 200 of the new Democrats (or 85 percent) hold seats in CityLab’s four most urban and suburban categories. Those districts include almost all of the Republican-held seats that Democrats captured last fall. In the three most urban categories of House seats, Democrats now crush Republicans, 149 to 16.

[Read: How Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez plans to wield her power]

Other measures also suggest that Democrats are now holding more defensible ground. In 2009, 49 House Democrats represented seats that had voted for John McCain in 2008. Even after November’s gains, only 31 Democrats now hold seats that voted for Donald Trump. Moreover, Republican DNA was more deeply engrained in those earlier split-ticket seats: Of the 49 Democratic-held seats that voted for McCain, 47 also voted for George W. Bush in 2004. This time, only 14 Democrats represent districts that voted for both Trump in 2016 and Mitt Romney in 2012, according to calculations by Tom Bonier, the chief executive officer of the Democratic voter-targeting firm TargetSmart. Just 13 House Democrats are in seats that Trump won by five points or more, Bonier calculates.

On social issues in particular, this heavy urban and suburban tilt should produce much greater unity than Democrats managed under Obama in 2009 or during their two years of unified government control under Bill Clinton in 1993 and 1994. In those Clinton years, the party faced widespread defections from rural and southern House members over gun-control measures. Now the party’s majority is rooted in suburban districts filled with white-collar and minority voters who lean left on most social issues, like gun control, gay rights, and immigration. “Certainly social issues are not going to divide the party, including guns,” says Gary C. Jacobson, a University of California, San Diego, political scientist who studies Congress.

To Jacobson’s point, Peter Ambler, the executive director of Giffords PAC, the gun-control organization founded by former Representative Gabby Giffords, said flatly in a post-election analysis that “Americans now have a gun safety majority in the House of Representatives.” According to the group’s count, 40 incoming House Democrats, almost all from urban and suburban seats, defeated Republicans with “A” rankings or better from the National Rifle Association. That’s a very different world than in 2009, when most of the rural House Democrats were determined to avoid crossing the NRA.

Similarly, it’s been revealing how few House Democrats have expressed concern about Trump’s attempts to portray the party as soft on border security during the government shutdown, which was triggered by his demands for $5 billion to fund a border wall. Democrats have even resisted efforts from Republican Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina to draw them into a more comprehensive negotiation that would link the wall to broader immigration reform. It’s difficult to imagine that the blue-dog Democrats could have been so confident or quiescent 10 years ago.

[Charles J. Sykes: A shutdown reveals the transformation of the GOP]

“In 2018, immigration did not hurt House Democrats in the places they won,” says Frank Sharry, the founder and executive director of America’s Voice, an immigration advocacy group. “Arguably, the issue hurt Republicans. As Trump closed by hammering on the caravan and immigrants as dangerous, the evidence is that a bunch of Republican and independent voters broke late for Democrats. Today’s Democrats just aren’t afraid of this issue the way many blue-dog Democrats were a decade ago.”

The League of Conservation Voters likewise sees a big shift from the last Democratic majority. Like gun-control groups, the organization had enormous success electing its endorsed candidates in suburban districts last fall; it’s running ads this week welcoming 18 members who expressed a strong commitment to action on climate change and transitioning away from fossil fuels. “There are far more members who campaigned on clean energy and climate issues, and who see it as both good policy and good politics,” said Gene Karpinski, the LCV’s president, in an email. “And the issue has much stronger support among the voters who brought them here.”

In this suburban-centered Democratic majority, the most important fissures will probably come over spending and the role of government. It’s likely that some of the new suburban members—several of whom have joined the centrist Blue Dog and New Democrat coalition groups—will resist expensive new initiatives to expand government’s reach (like single-payer health care) or new taxes. Those suburban members, holding districts that previously voted Republican, will inevitably be sensitive to the risk of alienating white-collar voters who dislike Trump and largely agree with Democrats on culture, but may still lean right on spending.

Those strains will take skill to manage. But they are unlikely to prove as daunting as the cracks in House Democrats’ foundation that the party experienced in previous majorities. In fact, compared with the fundamental fault line that defined Democrats through the 20th century—between conservative southern Democrats and more progressive non-southerners—and with the rural/urban divides that have strained them more recently, this new caucus has an opportunity to become the party’s most cohesive in modern times. “My guess is they will be highly cohesive and more liberal on the standard scales that we use to measure that,” Jacobson says.

In 2009, with its large rural contingent and the continued heavy presence of white men in its membership, the House Democratic caucus in key ways looked back to what the party had been. In 2019, with its urban/suburban geographic center; its huge advantages from states along the two coasts (including 46 seats from California alone); and the unprecedented gender, racial, and religious diversity of its members, the House caucus is looking forward to what Democrats are becoming.

That doesn’t guarantee them success at either passing an agenda or defending their majority in 2020. But on both fronts, it does mean that they are rowing with the current of change in the party—and not against it, as they were so often the last time Pelosi held the gavel.

Al Gore is mostly done with politics these days. Though he popped up at a campaign stop with Hillary Clinton in 2016, he’s otherwise safely in the very small group of nationally known Democrats not thinking of running for president in 2020.

But Gore remains engaged on his signature policy issue: climate change, for which the national political conversation is just starting to catch up to his warnings from decades ago. While he was a senator, through his eight years as vice president, and during his 2000 presidential campaign, Gore was tagged on the campaign trail as a global-warning alarmist obsessed with data and far-off predictions. Now, between the growing support for the Green New Deal in Congress and the presidential candidates railing against climate change, the Democratic Party has made aggressive action central to its developing identity.

The former vice president, who’s won an Oscar for his 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth and a Nobel Peace Prize for his environmental advocacy, speaks often at United Nations and other international meetings on climate change, events that some American officials and other prominent figures continue to attend despite President Donald Trump’s decision to stop sending official representatives on behalf of his administration.

What Gore hasn’t done much of, though, is talk directly about American politics and political candidates, including the dynamics within the party that nominated him for president 18 years ago.

Gore and I spoke recently for a story about Washington State Governor Jay Inslee, who is readying a presidential campaign that will make climate change and America’s response to it the central issue and cause. (Gore says he isn’t making an endorsement, or at least not yet.) We talked about why he thinks the national conversation on climate has changed and what he thinks hasn’t changed quickly enough. Here’s more of our interview, which has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Isaac Dovere: Where do you see the politics of climate change right now?

Al Gore: I think that we are extremely close to a political tipping point. We may actually be crossing it right about now. The much-vaunted tribalism in American politics has contributed to an odd anomaly, in that the core of one of our political parties is uniquely—in all of the world—still rejecting not just the science, but also the messages from Mother Nature that have pushed toward, and perhaps are pushing across, this political tipping point right now.

More and more people on the conservative side of the spectrum are really changing their positions now. This election, in 2020, is almost certainly going to be different from any previous presidential election in that a number of candidates will be placing climate at or near the top of their agenda. And I think that by the time the first primary and caucus votes are cast a year from now, you’re going to see a very different political dialogue in the U.S.

The climate-related extreme-weather events are causing millions of people who had successfully pushed this issue into the background and into the projected distant future to now be finding ways to talk about it and to express their deep concern.

Dovere: When you were in politics and talking about climate change, you were made fun of for it. Is that weird to think about now?

Gore: Forty years ago, it was not easy to get people’s sustained attention for this looming crisis. It’s much easier now.

Dovere: What do you make of the Democratic presidential contenders talking about climate change now?

Gore: Leaders who advocate solutions to the climate crisis should all run. There are several who have indicated they want to make this the No. 1 issue, who are in the midst of deciding whether to run or not. And I think it’s good for the country and good for the world to have this issue elevated into the top tier during this upcoming campaign.

Dovere: Every time there’s a new report on climate change, activists say, “We’ve got to get going before it’s too late.” And every time there’s a new report, climate-change deniers say, “Well, you said the world was ending the last time.” Do you think there’s actually a point when it will be too late?