Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the freshman New York representative, joins Intercept reporters Ryan Grim and Briahna Joy Gray for an in-depth conversation about her approach to politics and social media, her thoughts on the 2020 presidential election, and her out-of-nowhere congressional campaign. As a new member of the House Financial Services Committee, she’s already shaping the conversation with her call to raise the top marginal tax rate to 70 percent. Former North Carolina Rep. Brad Miller, a progressive Democrat who served for years on the Financial Services Committee, joins the conversation to talk about the challenges Ocasio-Cortez will face there.

Transcript coming soon.

The post Podcast Special: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on Her First Weeks in Washington appeared first on The Intercept.

The shutdown might be over for now, but President Donald Trump’s threat to declare a national emergency still looms. The continuing resolution passed Friday afternoon does not contain funding for a border wall, and the president has suggested that if Congress doesn’t compromise on a funding plan within three weeks, he may still proclaim a national emergency at the border.

When Trump first threatened to use emergency powers to unlock $5.7 billion for his $20 billion border wall project, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla. came out strongly against it — but not for humanitarian reasons or because he is concerned about an unmistakable creep toward authoritarianism. Rather, Rubio worried that normalizing the call for a state of emergency might make it easier for politicians to act on a genuine existential threat: “If today, the national emergency is border security,” said Rubio, “tomorrow, the national emergency might be climate change.”

Rubio is right to worry. Climate change is a legitimate emergency, unlike Trump’s border “crisis,” which is a fabrication sewn of foam-mouthed racism and vain partisan panic. Security and militarization at the border has increased steadily over the last decades; border crossings have been in decline for years; and most heroin smuggled over the border comes through legal border crossings, not the areas that are targeted for a wall.

Meanwhile, overwhelming scientific evidence says that climate change could take hundreds of millions of lives and trigger a global economic collapse in the next several decades, making anything we might recognize as human civilization physically impossible.

It’s not as if migration and climate are unrelated, either: Climate change is poised to cause the largest mass migration in human history, as millions are forced to leave homes rendered uninhabitable by rising sea levels, unbearable heat, and declining crop yields. Trump’s border and immigration policies, in other words, are climate policies, and efforts to restrict access to temperate parts of the world will be a defining political issue of the next century.

In addition to being justified, declaring a national emergency on climate change wouldn’t be all that novel. As Jeffrey Toobin pointed out in the New Yorker, the National Emergencies Act has been invoked 41 times since it was passed in 1976, and there are 31 emergencies currently in effect. What constitutes an emergency has never been clearly defined, and most of those currently in place allow the White House to place sanctions and restrictions on countries whose policies it disagrees with, such as regulating vessels that might enter Cuban waters or mobilizing the military as George W. Bush did in the days after 9/11.

Concerns about the expansion of executive authority are well-placed, but meeting the climate change goals recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change requires a level of mobilization that our balkanized, partisan government may be ill-equipped to handle. After all, decarbonization isn’t just about building a symbolic infrastructure project. It would involve transitioning every sector of the economy off fossil fuels at lightning speed. The sheer amount of administrative collaboration involved — across government agencies, industry, and civil society — is staggering, and would require massive levels of government investment and going toe-to-toe with one of the world’s most powerful industries.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., recently called the threat of climate change “our World War II.”Because of the effort and exigency involved, climate scientists are urging a “wartime footing” to decarbonize the economy over the next 16 years. They’re increasingly joined by politicians like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., who recently called the threat of climate change “our World War II” at a recent Martin Luther King Jr. Day event.

If climate change is our World War II, why shouldn’t our politicians should act like it?

As it became increasingly likely that the U.S. would enter World War II, Franklin Roosevelt and his advisers were eager to build up the country’s manufacturing capacity. But after years of feeling threatened by New Deal reforms, executives weren’t keen to have the state tell them what to do. Congress was also hesitant to appropriate more money to defense and have the state play a stronger role in directing industrial activity, mindful of public pushback to similar measures that were enacted during World War I.

But the cause of winning the war — an “unlimited” national emergency, as Roosevelt called it right before U.S. entry — was considered too important to be derailed by corporate executives or political squabbling. Declaring a limited national emergency in 1939 allowed the White House to begin its Protective Mobilization Plan, shifting resources to Britain’s Royal Navy, expanding military ranks, and building out industrial capacity to produce things like military aircrafts. Once Roosevelt declared a full national emergency after Pearl Harbor, federal agencies’ role in the economy was able to greatly expand. The government could now control prices and wages while directing industry leaders to meet manufacturing needs. Firms that refused to go along with government orders faced a federal takeover. By 1945, around a quarter of all U.S. manufacturing had been nationalized.

No doubt, this is the kind of outcome that terrifies Rubio. But without it, it’s not clear that the war effort would have been successful. And the pending battle against climate change is one that none of us can afford to lose.

There are serious risks to expanding executive authority. While Roosevelt’s war mobilization was ultimately critical to defeating Axis powers and ending the Depression, it also gave him the authority to intern over 100,000 Japanese-Americans, and wars abroad have reliably been an excuse to suppress civil liberties at home.

Because of these risks, and because leveraging the National Emergency Act sidesteps our democratic processes, it should be treated as a nuclear option. Such tools exist to intervene where our democratic processes fail. That said, there’s reason to suspect they already have.

Eighty-one percent of registered voters, an overwhelming majority, support a Green New Deal, and a record number of Americans are “very worried” about climate change. If the will of voters were democratically weighted, climate action would be a bipartisan priority. But we live in an oligarchy, where extreme wealth depresses the popular will. Energy executives are willing to throw tens of millions of dollars into blocking comparatively small-bore climate policies, blanketing airwaves with as much disinformation as is needed to get the job done. BP alone spent $13 million to defeat a modest carbon fee in Washington state last cycle. The resistance to an economy-wide mobilization like the Green New Deal will be orders of magnitude greater.

The climate crisis advances at the behest of a small handful of of executives and the politicians bought by them. Left unchecked, it will make any kind of organized global community impossible — let alone democracy. In such a context, it’s hard to argue that the status quo is more democratic than the alternative. The question for the next Democratic president, then, is whether they are prepared to put up at least as much of a fight to save the world as Trump has to build his wall.

The post Climate Change, Not Border Security, Is the Real National Emergency appeared first on The Intercept.

A Vale foi alertada sobre falhas nos procedimentos de controle e manutenção da barragem que se rompeu em Brumadinho, mas omitiu as informações para a população. Em seu Relatório de Impacto Ambiental, apresentado em 2017, a empresa cortou uma tabela importante que alertava para os riscos, produzida para um relatório de 2015. O documento de 2015 é o mesmo que serviu de base para a versão mais recente, de 2017, apresentado sem as informações sobre os riscos da barragem.

Os problemas na barragem foram identificados por uma consultoria contratada pela mineradora, a empresa Nicho Engenheiros Consultores Ltda, uma firma de Belo Horizonte com atuação nesse mercado desde 1990. O Intercept conversou com o dono da Nicho, o engenheiro Sérgio Augusto da Silva Roman, que assinou o estudo de impacto de Brumadinho como responsável técnico. A Vale precisava dos laudos para expandir a mineração em Brumadinho.

Questionado sobre a ausência das informações na versão divulgada ao público geral em 2017, Sérgio Roman diz que “não foi por omissão, mas porque não cabia mesmo”. Perguntado por que não cabia esse tipo de informação mesmo depois da tragédia ocorrida em Mariana, em 2015, o engenheiro justificou assim: “A população não ia entender porcaria nenhuma”.

Medidores danificados, drenos secosO documento é o Estudo de Impacto Ambiental (EIA), exigido de qualquer empreendimento que afete o meio ambiente. A papelada é a base dos processos de licenciamento. É a partir do documento e de vistorias próprias e eventuais pedidos de esclarecimentos que os órgãos de controle ambiental autorizam obras ou, se for o caso, determinam o cumprimento de “condicionantes” – medidas práticas que devem ser tomadas para que, aí sim, as licenças necessárias sejam dadas pelo governo. É um processo lento, geralmente proporcional ao tamanho do empreendimento.

Entre as mais de duas mil páginas redigidas a partir do trabalho de uma equipe de 27 profissionais, a Nicho listou falhas de segurança nas barragens da Vale em Brumadinho. Os problemas afetavam diretamente a Barragem I, a maior do complexo do Córrego do Feijão, justamente a que estourou no dia 25 despejando uma quantidade equivalente a 4.800 piscinas olímpicas lotadas de lama tóxica sobre funcionários da própria Vale e residências espalhadas na zona de mineração da empresa.

O estudo de impacto descreve, a partir da página 1.041, os métodos geralmente usados na indústria para controlar a segurança de barragens. Um monte de termos técnicos para basicamente dizer que alguns elementos são simples de observar (como fissuras superficiais e erosões), enquanto outros, praticamente invisíveis, demandam uma atenção muito maior e o apoio de instrumentos. O problema é que, segundo a consultoria contratada pela Vale, os instrumentos da gigante mundial da mineração não estavam em perfeitas condições.

Uma geringonça chamada piezômetro é essencial para a medição do nível da pressão exercida pelos rejeitos e pela água sobre a estrutura das barragens. O relatório diz que a Vale tinha 78 deles para medir diferentes pontos das barragens, mas quatro deles eram antigos (instalados oito anos antes) e “alguns foram danificados ou suspeita-se não estarem funcionando corretamente”. A pressão dos rejeitos sobre a parede de contenção é justamente o motivo mais evidente do rompimento. Pelo relatório, portanto, a Vale não poderia ter certeza, à época, de que a pressão estava sob controle, já que vários medidores eram antigos, estavam danificados ou sequer funcionavam. Perguntada, a empresa não respondeu se trocou os equipamentos.

Outro instrumento importante são os drenos, que conseguem medir a vazão da água. Nesse caso, indica a Nicho nas suas observações, “vários drenos encontram-se secos” – ou seja, não estavam medindo vazão nenhuma.

Numa espécie de puxão de orelha na mineradora, os especialistas da Nicho registraram que, “como princípio, a manutenção deve ser executada imediatamente após a identificação do problema evitando-se sua progressão, conjugação com outros e ameaça à segurança das Barragens I e VI”. Como os problemas foram encontrados naquele momento, era sinal, portanto, de que não havia reação imediata da Vale aos problemas (ou ao menos sobre parte deles).

Para apresentar às autoridades ambientais o impacto que determinado empreendimento terá no meio ambiente (árvores, rios, animais e também seres humanos), as mineradoras contratam empresas de consultoria independentes, com equipe formada por especialistas de diferentes áreas (de biólogos a geólogos, passando por engenheiros), para detalhar os possíveis impactos ambientais gerados pelas suas atividades. É uma exigência legal. Mas também uma relação de conflito de interesses intrínseca já que, no fim das contas, o objetivo do estudo é convencer o poder público a liberar as obras.

No caso da Vale, que desde 2003 explode montanhas na região do Córrego do Feijão em busca de minério de ferro, a contratada para produzir os laudos é a Nicho. Em agosto de 2015, portanto meses antes do rompimento da barragem da Samarco (controlada pela Vale) em Mariana, a Vale apresentou às autoridades ambientais de Minas Gerais mais de 2 mil páginas redigidas pela Nicho detalhando todo o projeto de expansão da operação de Brumadinho.

O Copam (Conselho Estadual de Política Ambiental, órgão de Minas Gerais responsável pela concessão da licença) nunca pediu esclarecimentos sobre os problemas apontados em relação à Barragem I.

Calhas entupidas e até formigasO engenheiro Sérgio Augusto da Silva Roman, da Nicho, que assinou o estudo de impacto de Brumadinho como responsável técnico, explica que a observação dos problemas se deu em vistoria presencial, mas que não caberia à sua empresa fazer uma análise mais pormenorizada da estrutura. “Nós que fazemos licenciamento só recebemos o projeto pronto. Pressupõe-se que todos os critérios técnicos e de segurança tenham sido obedecidos”, disse.

“A gente faz observação, [aponta que] tem tal problema. Mas dificilmente numa mina que já está operando o órgão ambiental vai dizer que não pode operar mais”, afirma. A barragem que estourou estava em operação desde a década de 1950. Segundo Roman, caberia ao órgão técnico pedir à Vale mais esclarecimentos, complementação de informações, para fazer uma análise mais profunda antes de conceder a licença. “Se o órgão ambiental diz que não tem problema, não sou eu que vou dizer que tem”.

Entre outros problemas encontrados, estavam também o acúmulo de sedimentos em calhas onde deveria escorrer água pela encosta da barragem e a presença de formigueiros na estrutura inclinada que liga o topo dela ao chão (se há formigueiros, sinal de que as formigas estavam penetrando no solo).

E, por fim, um outro problema de falta de prevenção: a Vale não produzia relatórios mensais de segurança das barragens. A empresa responsável pelo Estudo de Impacto Ambiental recomendou, então, que a Vale ou empresa contratada por ela passasse a emitir “mensalmente um parecer escrito sobre a condição das barragens, à luz dos resultados do monitoramento”.

Sobre o controle das barragens, a Vale afirmou em comunicado divulgado na última sexta-feira que vinha fazendo inspeções quinzenais na barragem e registrando suas observações em sistema controlado pela Agência Nacional de Mineração, órgão federal criado recentemente para regular o setor. A última inspeção foi realizada três dias antes do rompimento e, segundo a mineradora, “não detectou nenhuma alteração no estado de conservação da estrutura”.

Apesar dos problemas apontados, a empresa contratada pela Vale concluiu em 2015 que, “de acordo com inspeções realizadas pela Pimenta de Ávila Consultoria (2010), análises de documentos e monitoramento disponibilizados pela Vale, constata-se que a estrutura [da Barragem I], na situação atual, se encontra em condições adequadas de segurança”.

‘A população não vai entender porcaria nenhuma’Dois anos depois do primeiro estudo, em maio de 2017, a Vale e a Nicho apresentaram aos órgãos ambientais uma nova versão do documento, agora já batizado como Relatório de Impacto Ambiental (RIMA). Não era de fato um novo relatório. Era apenas uma versão resumida do estudo feito anteriormente, com as mesmas conclusões e uma capa mais bonita. Em vez de 2.114 páginas, eram 238.

Como a Vale explica, esse novo relatório “trata das principais conclusões sobre a região e o empreendimento, sendo apresentadas de forma resumida e clara para que a população entenda o projeto, bem como as consequências ambientais de sua implementação”. E sugere que as pessoas interessadas leiam o Estudo de Impacto Ambiental, com suas mais de duas mil páginas cheias de jargões do mundo da mineração – mas que só ficaria disponível para consulta pública, segundo a própria Vale, depois da aprovação do empreendimento pelos órgãos competentes. A divulgação de estudos de impacto ambiental antes da aprovação do empreendimento é vetada por uma resolução do Conselho Nacional de Meio Ambiente, de 1986.

Faria falta a leitura completa, porque, no resumo, a Vale e a Nicho esqueceram de informar à população sobre as observações críticas feitas pela equipe de especialistas aos procedimentos de controle e manutenção das barragens. Na verdade, as barragens, embora sejam parte importante do projeto de expansão, são comentadas apenas em uma página do relatório (pág. 36). E sem referências críticas.

Dinheiro extraído da barragemAs barragens mereciam um maior destaque no relatório. A Vale pretendia aumentar seus lucros explorando os rejeitos depositados na Barragem I. Explicando de maneira simplificada: geralmente os restos não aproveitados do processo de transformação do ferro bruto extraído das montanhas em produto comercializável vai para a lata de lixo – ou seja, para as chamadas barragem de rejeitos, uma espécie de fossa sanitária gigante a céu aberto.

Acontece que, desde antes da tragédia ambiental de Mariana, a Vale tenta obter a aprovação do governo de Minas Gerais para poder mexer nessa barragem já lotada (e, portanto, inativa) para drenar rejeitos para uma nova etapa de processamento.

Nesse novo processo, os rejeitos seriam transferidos a partir de um duto de cerca de 1,5 km de extensão, a ser construído, para que fossem transformados em “pellet feed” (um minério super fino, com menos de 0,15 mm de espessura). Trata-se de um minério menos valorizado, mas, ainda assim, é dinheiro. Como a equipe da Nicho Engenheiros citou no Estudo de Impacto Ambiental, um pesquisador da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais analisou a importância econômica desse reaproveitamento de rejeitos pelas mineradoras e apontou que essas intervenções são feitas de forma “que seja traduzida em maior margem de lucro”.

Antes que essa transferência pelo chamado rejeitoduto começasse, a Vale pretendia colocar retroescavadeiras em cima da barragem (que é resistente no topo) até quando fosse possível (ou seja, antes que as escavadeiras começassem a afundar na lama movediça). Para que as escavadeiras pudessem fazer o trabalho em segurança, o nível da água no fundo da barragem de rejeitos deveria ser diminuído gradativamente.

Como se viu, a Vale pretendia mexer num gigante adormecido. No início de dezembro passado, a companhia finalmente conseguiu autorização para fazer isso. Pouco mais de um mês depois, a barragem inativa que a Vale teve autorização para colocar retroescavadeiras em cima se rompeu e sua lama tóxica matou dezenas de pessoas.

Tudo certo, segundo a ValeAs investigações oficiais sobre o desastre ainda estão apenas começando, então não se tem informação definitiva sobre os procedimentos de controle e prevenção que vinham sendo efetivamente realizados pela Vale em Brumadinho. A mineradora tem dito que fez tudo certo e que as barragens eram seguras.

Em comunicado divulgado horas após o rompimento da barragem, a Vale informou que a estrutura “possuía Declarações de Condição de Estabilidade emitidas pela empresa TUV SUD do Brasil, empresa internacional especializada em Geotecnia”. A última declaração tinha sido emitida em setembro passado, segundo a mineradora, referente “aos processos de Revisão Periódica de Segurança de Barragens e Inspeção Regular de Segurança de Barragens”. Ainda segundo o comunicado da Vale, “a barragem possuía Fator de Segurança de acordo com as boas práticas mundiais e acima da referência da Norma Brasileira”.

O Intercept enviou alguns questionamentos para a Vale na noite de domingo, mas, até o fim da manhã de hoje, a empresa ainda não respondido três de nossas perguntas:

A Vale produzia o parecer mensal de segurança das barragens I e VI, conforme recomendado pela equipe responsável pela produção do Estudo de Impacto Ambiental do projeto de expansão da Córrego do Feijão/Jangada? Em caso positivo, a companhia pode fornecer uma cópia dos três últimos pareceres? Caso esses pareceres não tenham sido produzidos, qual a justificativa da companhia para o não cumprimento da recomendação presente no EIA?

A Mina Córrego do Feijão foi objeto de alguma fiscalização ambiental nos últimos três anos? Em caso positivo, a empresa apresentou às autoridades ambientais o relatório previsto no Parágrafo 5º do Artigo 7º da Deliberação Normativa COPAM nº 87, de 17 de junho de 2005?

Por que a Vale apresentou, em 10 de maio de 2017, uma versão resumida do Relatório de Impacto Ambiental originalmente apresentado em 4 de agosto de 2015, sem referências às observações críticas sobre a Barragem I?

Vamos atualizar a reportagem com as respostas, se elas vierem.

Bombeiros se esforçam para encontrar sobreviventes após o rompimento da barragem.

Foto: Mauro Pimentel/Getty Images

The post Vale sabia de problemas na barragem e omitiu os riscos em documento público appeared first on The Intercept.

More than two years after Donald Trump’s inauguration ushered in sweeping changes to the nation’s immigration enforcement system, accounts of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arresting undocumented immigrants in and around New York courts have increased by 1,700 percent, according to a new report.

The expanded courthouse operations have been coupled with increased reports of New York-based immigration agents using physical force to take undocumented immigrants into custody, the Immigrant Defense Project said Monday.

“ICE operations increased not only in absolute number but grew in brutality and geographic scope” from 2017 to 2018, the IDP report found, with plainclothes agents in New York relying on “intrusive surveillance and violent force to execute arrests.”

Included in the new report are accounts of New York-based agents grabbing people off the street as they attempt to go to or leave court, shuffling them into unmarked cars, and refusing to identify themselves as bewildered family members look on.

“This report shows that ICE is expanding surveillance and arrests in courthouses across the state, creating a crisis for immigrants who need access to the courts,” Alisa Wellek, IDP’s executive director, said in a statement. “We cannot allow ICE to turn New York’s courts into traps for immigrants.”

ICE did not respond to a request for comment Monday.

Relying on a network of attorneys, legal organizations, and a publicly accessible hotline, IDP has tracked ICE enforcement tactics for years. According to the organization, Trump’s ascent to the White House was followed by a surge in courthouse arrests unlike anything advocates in New York had ever seen, with the total number of arrests reported in 2017 and 2018 numbering 374, compared to 11 in 2016.

IDP has also tracked ICE tactics outside courts and in New York communities, releasing an interactive map in 2018 documenting the agency’s increased use of predawn raids and ruses — often involving ICE agents pretending to be New York City police officers — in order to arrest undocumented immigrants.

Last year not only saw an increase in reported courthouse arrests in New York City, IDP’s latest report found. The organization also documented courthouse arrests in new locations, including several upstate New York counties, and what the advocacy group described as the targeting of “particularly vulnerable immigrants including survivors of human trafficking, survivors of domestic violence, and youth” at court.

“In the vast majority of operations, ICE agents refused to identify themselves, explain why an individual is being arrested, or offer proof that they have reason to believe that the individual they’re arresting is deportable,” the report said. “This occurred despite the fact that internal agency regulations require them to provide this information.”

The increase in courthouse arrests in New York followed the issuance of a new directive on such operations, signed by former ICE Acting Director Thomas Homan, who once told lawmakers that undocumented people should live in fear of his agency.

Echoing the administration’s anti-“sanctuary city” rhetoric, the January 10 directive argued that “courthouse arrests are often necessitated by the unwillingness of jurisdictions to cooperate with ICE in the transfer of custody of aliens from their prisons and jails.”

The directive went on to say that family members and friends encountered during a courthouse arrest “will not be subject to civil immigration enforcement action, absent special circumstances,” and “ICE officers and agents should generally avoid enforcement actions in courthouses, or areas within courthouses that are dedicated to non-criminal (e.g., family court, small claims court) proceedings.”

According to the IDP report, ICE has not only expanded courthouse arrests since the directive was issued — its New York agents have also arrested family members present during operations and carried out arrests in noncriminal courts.

Physical Assaults by ICE AgentsIn November, The Intercept published video, originally obtained by IDP, of ICE agents and New York state court officers arresting an undocumented man outside the Queens County Criminal Court. Included in Monday’s report, the man’s arrest is part of a broader pattern described by IDP as “one of the most striking changes in ICE operations” in 2018.

“Over the past year, IDP has received reports of ICE agents tackling individuals to the ground, slamming family members against walls, and dragging individuals from cars in front of their children,” the report said. “They have also pulled guns on individuals leaving court. In one incident, ICE officers physically assaulted an attorney who was 8 months pregnant.”

In one case documented in the report, a mother and son were leaving Brooklyn’s criminal court when two men in plainclothes grabbed the son and began dragging him toward an unmarked car. Fearing that she was witnessing her son’s kidnapping, the woman asked the men who they were but received no answer. A third officer, according to the report, showed up and shoved the woman against the wall, repeatedly telling her to “shut up.”

“The officers then drove away, leaving his mother sobbing on the street, panicked that her son had been kidnapped,” the report said. “She did not know it was ICE agents who arrested him until she received a call from her son in an ICE processing facility later that day.”

A second incident documented in the report also invoked the sense of kidnapping in progress.

“A man was leaving the Brooklyn Supreme Court with his attorney and family when he was suddenly surrounded by plainclothes ICE agents,” the report said. After throwing him against a wall and refusing to identify themselves to his attorney, the agents bundled the young man into an unmarked car with no license plates.

According to the report, “several bystanders witnessed the commotion and one woman, believing that the man was being kidnapped, called 911.”

The IDP is now pushing for legislation — the Protect Our Courts Act — to put an end to ICE’s use of courthouse arrests in New York. According to Wellek, the IDP executive director, “The New York state legislature must act now to pass the Protect Our Courts Act to prevent ICE from continuing these harmful practices.”

The post ICE Courthouse Arrests in New York Increased 1,700 Percent Under Trump appeared first on The Intercept.

Most of the data collected by urban planners is messy, complex, and difficult to represent. It looks nothing like the smooth graphs and clean charts of city life in urban simulator games like “SimCity.” A new initiative from Sidewalk Labs, the city-building subsidiary of Google’s parent company Alphabet, has set out to change that.

The program, known as Replica, offers planning agencies the ability to model an entire city’s patterns of movement. Like “SimCity,” Replica’s “user-friendly” tool deploys statistical simulations to give a comprehensive view of how, when, and where people travel in urban areas. It’s an appealing prospect for planners making critical decisions about transportation and land use. In recent months, transportation authorities in Kansas City, Portland, and the Chicago area have signed up to glean its insights. The only catch: They’re not completely sure where the data is coming from.

Typical urban planners rely on processes like surveys and trip counters that are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and outdated. Replica, instead, uses real-time mobile location data. As Nick Bowden of Sidewalk Labs has explained, “Replica provides a full set of baseline travel measures that are very difficult to gather and maintain today, including the total number of people on a highway or local street network, what mode they’re using (car, transit, bike, or foot), and their trip purpose (commuting to work, going shopping, heading to school).”

To make these measurements, the program gathers and de-identifies the location of cellphone users, which it obtains from unspecified third-party vendors. It then models this anonymized data in simulations — creating a synthetic population that faithfully replicates a city’s real-world patterns but that “obscures the real-world travel habits of individual people,” as Bowden told The Intercept.

The program comes at a time of growing unease with how tech companies use and share our personal data — and raises new questions about Google’s encroachment on the physical world.

If Sidewalk Labs has access to people’s unique paths of movement prior to making its synthetic models, wouldn’t it be possible to figure out who they are, based on where they go to sleep or work?Last month, the New York Times revealed how sensitive location data is harvested by third parties from our smartphones — often with weak or nonexistent consent provisions. A Motherboard investigation in early January further demonstrated how cell companies sell our locations to stalkers and bounty hunters willing to pay the price.

For some, the Google sibling’s plans to gather and commodify real-time location data from millions of cellphones adds to these concerns. “The privacy concerns are pretty extreme,” Ben Green, an urban technology expert and author of “The Smart Enough City,” wrote in an email to The Intercept. “Mobile phone location data is extremely sensitive.” These privacy concerns have been far from theoretical. An Associated Press investigation showed that Google’s apps and website track people even after they have disabled the location history on their phones. Quartz found that Google was tracking Android users by collecting the addresses of nearby cellphone towers even if all location services were turned off. The company has also been caught using its Street View vehicles to collect the Wi-Fi location data from phones and computers.

This is why Sidewalk Labs has instituted significant protections to safeguard privacy, before it even begins creating a synthetic population. Any location data that Sidewalk Labs receives is already de-identified (using methods such as aggregation, differential privacy techniques, or outright removal of unique behaviors). Bowden explained that the data obtained by Replica does not include a device’s unique identifiers, which can be used to uncover someone’s unique identity.

However, some urban planners and technologists, while emphasizing the elegance and novelty of the program’s concept, remain skeptical about these privacy protections, asking how Sidewalk Labs defines personally identifiable information. Tamir Israel, a staff lawyer at the Canadian Internet Policy & Public Interest Clinic, warns that re-identification is a rapidly moving target. If Sidewalk Labs has access to people’s unique paths of movement prior to making its synthetic models, wouldn’t it be possible to figure out who they are, based on where they go to sleep or work? “We see a lot of companies erring on the side of collecting it and doing coarse de-identifications, even though, more than any other type of data, location data has been shown to be highly re-identifiable,” he added. “It’s obvious what home people leave and return to every night and what office they stop at every day from 9 to 5 p.m.” A landmark study uncovered the extent to which people could be re-identified from seemingly-anonymous data using just four time-stamped data points of where they’ve previously been.

There are also lingering questions about how Sidewalk Labs sets limits about the type and quality of consent obtained. As the past year’s tsunami of privacy breaches has shown, many users do not understand how closely they are being tracked and how often their data is being resold to advertisers or third parties or programs like Replica. “We need to do a better job in ensuring the type of express consent commensurate with sensitivity of data is actually being enforced when data is collected,” Israel noted. Consent has historically been defined by broad and vague terms of service, leveraging companies’ knowledge of intricate technical details at the expense of users too pressed for time to read — let alone understand — their jargon-laden privacy policies. The Times investigation found, for instance, that “the explanations people see when prompted to give permission are often incomplete or misleading.” Even while they may retain a broad right to sell or share location data in an opaque privacy policy, many apps do not explicitly tell their users that they are doing so.

It’s difficult to evaluate who might be consenting when it’s not clear where the data comes from. Sidewalk Labs explains that Replica’s data is purchased from telecommunications companies and companies that aggregate mobile location data from different apps. “We audit their practices to ensure they are complying with industry codes of conduct,” said Bowden. “No Google data is used. This extensive audit process includes regular reporting, interviews, and evaluation to ensure vendors meet specified requirements around consent, opt-out, and privacy protections.”

Yet because the exact sources of data have not been revealed, it is unclear whether Replica draws from the ranks of unregulated apps that profit from indefinite privacy policies to continuously collect users’ precise whereabouts. Publicly available documents from cities piloting or purchasing Replica offer conflicting information about Replica’s exact sources of data. A document from the Illinois Department of Transportation describes Replica’s data sources as “mobile carrier data, location data from third-party aggregators and Google location data, to generate travel data for a region.” This data sample, it adds, “is not limited to Android devices” and “is collected from individuals for months at a time, allowing for a complete picture of individual travel patterns.” In Portland, documents filed with its city council state that the data is sourced from “Android Phones and Google apps.” Officials at the Portland Bureau of Transportation told Oregon Public Broadcasting that some of the sources of Sidewalk Lab’s mobile location data may also come from other sources, not yet known to them. Minutes from a regional transit planning meeting for Kansas City suggest that it’s possible for Replica “to get data on things like Uber & Lyft,” while a city PowerPoint states that the tool is “based off of Google data.”

At stake with Replica is the value that can be produced by aggregating data about our movements and then selling it back to governments. The program was originally pitched by Sidewalk Labs “to support the development” of Quayside, the controversial “smart” city planned for Toronto’s eastern waterfront. (A Sidewalk Labs spokesperson told The Intercept that there are no plans to bring Replica to Toronto.) Yet Torontonians have been watching Replica’s plans closely. Some see the project as an example of the way the proprietary tools and techniques developed by Sidewalk Labs at Quayside might be exported — or imported — to other cities, without creating any additional economic benefits for the residents who have produced this data.

“Replica is a perfect example of surveillance capitalism, profiting from information collected from and about us as we use the products that have become a part of our lives,” said Brenda McPhail, director of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association’s Privacy, Technology, and Surveillance Project. “We need to start asking, as a society, if we are going to continue to allow business models that are built around exploiting our information without meaningful consent.”

The post Google’s Sidewalk Labs Plans to Package and Sell Location Data on Millions of Cellphones appeared first on The Intercept.

Two previous posts—“When the Top U.S. Tax Rate was 70 Percent—or Higher” and “Who Is Paying Their ‘Fair Share’?”—went into the endlessly complex and newly politically relevant question of the “fairness” of the American tax system.

The question is complex for obvious reasons. It’s politically relevant as evidence comes in about the effects of the Trump-Republican tax cut of 2017, and as Democratic proposals come forth to raise top-bracket tax rates again—for instance, as high as 70 percent (which was their minimum level between 1932 and 1982).

A huge torrent of mail has arrived, of which I expect this will be the next-to-last sampling. Not the very last, because there’s a technical issue I want to understand better before posting information about it. But next-to-last, because there’s a limit on fresh perspectives.

Here we go, with numbered entries and a brief blurb on the perspective each one represents.

1) “Stop saying that high marginal tax rates ‘Made America Great’ in the first place.” Several previous reader-messages have stressed the high tax rates during America’s post-World War II growth decades, as a sign that higher top-bracket rates could be valuable once again. Here is a long, detailed response to that argument, from a reader on the West Coast:

The argument, if you can call it that, over the top marginal tax rate vs national economic well-being is—in my opinion—a correlation vs causation pissing match that takes as its subject an issue of secondary or tertiary importance at best.

It’s fun to bash the tennis ball back and forth across our contemporary social and political divides about the rich and rates, but the absolute, fundamental fact about the United States after the Second World War (which seems to be the consensus Lost Golden Age) was that it had been dealt not only all the aces in the global economic poker hand, but most of the face cards as well. To recap:

The physical industrial capacity of the most advanced industrial economies of Europe and Asia ranged between meaningfully damaged and nearly destroyed. The United States by contrast had just invested tremendous amounts of human energy in the construction of productive infrastructure that no one ever attacked. The United States suffered less than 3 percent of the war’s combatant deaths and less than 1 percent of the total global death toll. Considering combatant deaths only, the US suffered in absolute terms about one fifth of the deaths of Japanese soldiers, less than one tenth the deaths of German soldiers, and less than one twentieth the deaths of Soviet soldiers. US military deaths were fewer than those of Yugoslavia. These numbers of course skew even further in the U.S.’s favor when considering total deaths including civilians, and then again when considering total deaths as a percentage of prewar populations. The United States was the refuge of choice for scientists and other intellectuals who fled Europe, i.e. there was a tremendous brain drain in the U.S.’s favor The U.S. had the advantage of significant natural resources in energy and materials (oil, coal, metals). Ethnic tensions were controlled e.g. via the violent subjugation of black Americans, to take only the most obvious and terrible example. The U.S. had as ready markets all the degraded and destroyed industrial economies of the world to export its goods to, with unprecedented demand for capital goods to rebuild those economies.In sum, for a good twenty and arguably thirty to forty years after the war, the U.S. had by far the largest and most advanced industrial infrastructure in the world, the least damaged and probably best-educated workforce, social cohesion built not incidentally on the repression of ethnic minorities, nearly free energy from oil & coal, and buyers around the world in urgent need of America’s manufactures.

That is the primary set of facts about America the Great that we should keep always front of mind. It seems of little relevance, in light of that combination of facts, whether the top marginal rate in 1955 was 50 percent or 70 percent or 90 percent. The U.S. would have had to shoot its golden goose in the head at point blank range, possibly more than once, in order to kill it.

I am not far-seeing enough to predict all the consequences, intended and otherwise, of changes made now to the tax code or even of changes to the distribution of the tax burden. What I know is that the global competitive landscape has changed permanently, and bears little resemblance to that of 1955.

I would submit that asking “what is the relationship between top tax rates and economic growth in the U.S.” ignores more or less every factor of primary economic importance. A better place to start might be by asking “are there periods in economic history, in the last twenty years or prior to WWI (say), in which we can cleanly (?) observe the impact of dramatic changes to the tax burden paid by the capital-holding and capital-allocating class upon the economic performance of one or more industrial economies participating in high-level import-export competition with other like economies."

2) “Yes, the economy has changed since the 1950s. It’s changed by becoming more unfair.” A reader makes a contrary argument, about the shifts in the economic landscape since the post-war growth decades:

I think one of the main reasons for having a 70-90 percent tax on the highest income people is to reinstate a feeling of fair play in this country. This has been lacking in the last 40 years ever since wages have stagnated for most of us, taxes on the wealthy have gone down, and the wealthy have taken control of the government via lobbying, Citizens United, etc.

Every game needs equal opportunities and fair rules equally applied to everyone. If it doesn't people get tired of playing and tip over the board. That's what's happening to this country and around the world.

The rich people's claim that "upskilling" (a Davos term) workers will reduce the wealth gap and income inequality is a fallacy.

I'm an M.S. level biochemist with an MBA and some okay computer skills working as a knowledge worker, and making a solid middle class income, and my fellow employees and I are lucky to get a 2.5 percent yearly raise, while we see the top managers make hundreds of thousands a year and up to over a million/year and get big bonuses.

You can't get too much more upskilled than me or my colleagues, and we're still falling further and further behind the wealthy.

3) Yes, it really is more unfair. Continuing the argument in #2, from another reader:

In discussing the changes in average tax rates for the (as reference

points) the bottom 50 percent and the top 1 percent of incomes, it is also useful to keep in mind the changes in incomes for those groups. Since 1980, median household income (half make more, half make less) has been essentially flat. Labor productivity (and resulting GDP growth) has continued at near the historic (since 1800) rate, but virtually all the additional income has gone to the top 10 percent, and most of that to the top 1 percent.

The share of all income going to each of the four lower quintiles (the bottom 20 percent of households, the next 20 percent, etc.) has decreased since 1980. The portion going to the top 20 percent has, of course, increased (and, to repeat, most of that has gone to the top 1 percent).

The point of all this is that the situation is even more serious than

would be suggested by the data sent by other readers. The bottom 50 percent are paying a higher percentage of an essentially unchanged income, while the top 1 percent are paying a lower percentage of vastly higher incomes.

Higher (marginal) tax rates for the very well off would be part of a program to address income inequality, but only part. The discussion,

though, should also explicitly include the dramatic (and apparently growing) increase in income inequality since 1980.

4) Rebuild America, through more public spending. An extension of arguments #2 and #3, from another reader:

If I were a Democratic strategist, I would point to our nation's once great and groundbreaking infrastructure, started / built / rebuilt largely under FDR and in the few decades immediately post-WWII and which is so desperately in need of upgrades or even basic maintenance these days and I'd brand today's conservatives as freeloaders sponging off the hard work of Americans from the past—including conservatives from Eisenhower's time, who realized patriotism meant a certain level of sacrifice by all for the good and safety of all.

5) “The things I remember were roads, tall buildings, universities and research.” Finally for today, from a reader who is a small-business owner in North Carolina.

In the 1950s the marginal income tax rate was high. But we were in the height of the cold war. So, in those days was the money taken in taxes turned back into our “military/industrial” economy in a way that grew the overall economy?

[JF note: through some of the early Cold War years, military spending neared 10 percent of the GDP. In recent decades, it’s been closer to 5 percent—of a much larger GDP. But whether those big defense budgets helped the long-term U.S. economy, rather than distorting it, has been a long-term source of serious contention. In the mid-1970s, Seymour Melman, of Columbia, wrote his influential book The Permanent War Economy, arguing that large military budgets would be a significant long-term drag on American economy. I see that I wrote a review of this book for the New York Times, when it first came out nearly 45 years ago.]

And is the difference that today that a high percentage of taxes are used for income transfer between rich and poor and younger and older? And therefore with much less GDP impact?…

And what about local property taxes? In the postwar as the South industrialized what was the contribution of industrial property to the tax base vs. the individual property tax on a home? As far as I know companies weren’t bribing, and whining for all sorts of tax concessions because they were so special. Could it be that when corporate ownership was still local they may have even had a bit pride in paying the taxes and seeing the civic improvements they paid for?

I was born in North Carolina in 1959. But as I started work in the early 1980s I got the impression people in other parts of the country were surprised that I had shoes. The things I remember were roads, tall buildings, universities and research. A state proud to show progress from subsistence to the modern age. Today there seem to be people that want to take us back to 1950, or maybe more realistically, 1850.

How did we get to where we can’t even maintain what our ancestors built, much less build for our own time?

U.S.-China tensions are boiling, as trade talks resume. The Justice Department stoked the flames with China by levying charges of bank fraud and obstruction of justice against an executive at the Chinese telecom firm Huawei. The crisis could pose a major impasse for Beijing’s goal of transforming the country into a technology powerhouse.

In the U.K., Prime Minster Theresa May’s Brexit headaches are never-ending, as she looks to the Brussels again for concessions on her country’s formal plan to leave the EU. This week looks to be yet one more crucial test of her leadership, which has weathered a string of high-profile cabinet resignations and no-confidence votes.

One thing is clear about 2020: Everyone’s already testing the waters. Kamala Harris sent an early signal to her Democratic primary opponents that she’ll be tough to outmaneuver, drawing a crowd of 22,000 for her inaugural campaign rally. Another, very different type of candidate is also floating his name for the presidency—Howard Schultz, the man who built Starbucks into a global behemoth, who is mulling a run as an independent. That has raised the hackles of Democrats who think he would instead help Trump win reelection, but David Frum argues that Schultz’s exploration may just be “the help America needs.”

The best films after week one at Sundance: The festival has long been a launching pad for flicks to find mainstream success—and Oscar accolades. Of the 17 movies our critic David Sims viewed during the festival’s first week, The Farewell stuck with him the most. It’s a humor-filled drama that tells the story of the director Lulu Wang’s family, who try to prevent a grandmother from finding out about her terminal illness during a family reunion. Late Night has ginned up the most buzz, in part because it stars and is written by Mindy Kaling, but also because Amazon forked up an eye-popping $13 million for the rights to the film.

Evening Reads

(Jun Cen)

Thousands of years ago, 50,000 acres of glacial ice crusted Venezuela’s peaks. By 1910, maps showed that these glaciers had shrunk to 2,500 acres. By 2008, fewer than 80 acres remained.

Now, amid political and economic chaos in Venezuela, scientists are racing to study the one small remaining glacier.

“This past fall, the only trained microbiologist left in the laboratory was Johnma Rondón, the second-youngest researcher on the entire Vida Glacial project team. Rondón, who helped identify the microbial strains from the glaciers as part of his doctoral dissertation, was responsible for maintaining the strains stored in the freezers in Yarzábal’s lab—no easy task in a country where power failures are frequent.”

→ Read the rest.

(Natural History Museum Rotterdam)

A Dutch man’s drug- and alcohol-induced decision in 2016 to swallow a live catfish led to a frantic visit to the emergency room, but the grisly practice of gulping down a fish has a surprisingly long backstory as a party game. The tradition stretches back to 1939, and it took off from there:

“A Harvard sophomore won local notoriety—and job offers from multiple circuses—that same year after swallowing 23 goldfish in just 10 minutes. Soon students at other schools were vying to break the record, and the Intercollegiate Goldfish Gulping Association (IGGA) was established to determine and enforce competition standards. There were only two rules: first, that each fish measured three inches long, and second, that the fish be kept down for at least 12 hours after consumption.”

→ Read the rest.

(Louisa Gouliamaki / AFP / Getty)

The above photograph depicts demonstrators in this city on January 20, 2019, protesting an agreement to rename which neighboring country?

(For answers, scroll down to No. 9 in this gallery of striking images from around the world.)

Dear Therapist

(Bianca Bagnarelli)

Every Monday, Lori Gottlieb answers questions from readers about their problems, big and small. This week, Ginger from Rochester, New York, writes:

“I’ve been dating Adam for two and a half years. I’m 33 and childless, and he’s 48, divorced, and the father of three kids. We seem to keep having the same fights about his needy ex-wife and the negative impact she has on our relationship.”

→ Read the rest, and Lori’s response. Have a question? Email Lori anytime at at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult throughout the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

It’s Monday, January 28. Federal employees are back to work today after the 35-day partial government shutdown, but the economy took an $11 billion hit, according to a report from the Congressional Budget Office. Speaker Nancy Pelosi has now invited President Donald Trump to deliver the State of the Union address on February 5, after the planned January 29 address was postponed following the government shutdown standoff.

The Latest: National-Security Adviser John Bolton announced that the U.S. is imposing sanctions on a Venezuelan state-owned oil firm as part of an effort to oppose President Nicolás Maduro. Last week, in a decidedly un-Trumpian move—off Twitter, amid concerted diplomatic efforts—the administration recognized the country’s opposition leader, Juan Guaidó, as its legitimate president.

A Show of Strength: California Senator Kamala Harris officially launched her presidential bid on Sunday at a massive rally in Oakland—part of her team’s broader plan to start the campaign season off strong. But presidential races are all about timing, one Democratic adviser told Edward-Isaac Dovere, “and traditionally being the first to peak is not the right time.” Meanwhile, the former Starbucks CEO, Howard Schultz, is taking a different approach as he ponders running in 2020—as an independent.

Behind the Scenes: “I would be happy if not a single refugee foot ever again touched America’s soil,” the senior adviser Stephen Miller reportedly once told Cliff Sims, an obscure former administration staffer who’s now written a new tell-all book about the chaos of working in the Trump White House. The Atlantic obtained an early copy of the book, which is filled with such jaw-dropping details.

Democratic Senator Kamala Harris speaks as she formally launches her presidential campaign at a rally in her hometown of Oakland, California, on Sunday. (Tony Avelar / AP)

Ideas From The AtlanticTrump’s Lawyers Need to Worry About More Than Winning (Bob Bauer)

“Trump’s lawyers have the professional independence and ethical responsibility to do what they can to divert him from this path, or any other, that leads to serious harm to the nation’s democratic processes and institutions.” → Read on.

Trump Is Destroying His Own Case for a National Emergency (Elizabeth Goitein)

“A president using emergency powers to thwart Congress’s will, in a situation where Congress has had ample time to express it, is like a doctor relying on an advance directive to deny life-saving treatment to a patient who is conscious and clearly asking to be saved.” → Read on.

The Terrorism That Doesn’t Spark a Panic (Adam Serwer)

“But there’s one spike in violence that the president rarely acknowledges or even mentions, and it’s the rise in far-right terror that has accompanied his ascension to the White House.” → Read on.

The Ex-Starbucks CEO May Save the Democratic Party From Itself (David Frum)

“If you seriously believe that the Trump presidency presents a unique threat to American democracy, you want the safer choice, not the risky one. You want the candidate with the broadest possible appeal, not the most sectarian.” → Read on.

◆ How Every Member Got to Congress (Sahil Chinoy and Jessica Ma, The New York Times)

◆ Poor Southerners Are Joining the Globe’s Climate Migrants (Lewis Raven Wallace, Environmental Health News)

◆ Why We Need to Be Wary of Narratives of Economic Catastrophe (Jeremy Adelman, Aeon)

◆ The Foolish Quest to Be the Next Barack Obama (Bill Scher, Politico Magazine)

◆ Iowa Nice: Hawkeyed Experts Say Elizabeth Warren Hit Ground Running (Ben Jacobs, The Guardian)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily, and will be testing some formats throughout the new year. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

Every year since the Sundance Film Festival began, in 1985, the founder and figurehead, Robert Redford, has kicked off the event with a discussion of the featured movies and the state of independent cinema. Named after one of Redford’s most iconic characters, the annual Utah gathering was designed to foster filmmaking talent outside of the studio system. But this year, Redford made something clear: He no longer needs to be in the spotlight. After a brief introduction, he stepped aside at the opening press conference. “I think we’re at a point where I can move on to a different place,” he said, ceding the stage to the executive director, Keri Putnam.

Sundance has debuted films from some of indie cinema’s most prominent voices over the past 30-plus years, including Steven Soderbergh, the Coen brothers, Todd Haynes, and recent Grand Jury Prize winners such as Damien Chazelle and Ryan Coogler. But in stepping back, Redford is acknowledging the welcome ways in which the festival continues to evolve: Some 40 percent of this year’s movies were directed by a woman, and 36 percent were made by people of color. Meanwhile, 63 percent of the accredited press come from “underrepresented groups,” Putnam said.

[Read: What to expect at this year’s Sundance Film Festival]

Since arriving at Park City last week, I’ve seen 17 movies, cramming in screenings in search of breakout hits, exciting new voices, and less heralded gems that could easily get lost in the mix. Sundance is a place for movies to make a splash and get picked up for large sums of money by big studios, but it’s also where unproven directors can debut work alongside veteran filmmakers. In fact, some of the strongest projects I’ve seen so far come from names I’d never heard before.

The Farewell (A24)

The Farewell (A24)The most outstanding movie I saw during the festival’s first, packed weekend of programming was Lulu Wang’s The Farewell, the second film from the Chinese-born writer and director, who moved to the United States at a young age. The Farewell dramatizes an incredible personal story, one that Wang told on an episode of This American Life: Her grandmother is diagnosed with a terminal illness, and her extended family decides to keep the news secret from the matriarch during a big reunion. Awkwafina plays an American-raised granddaughter Billi, whose desire to tell her grandmother what’s really happening is tied to her larger unresolved sorrow over leaving her homeland as a child.

The script is packed with mundanely funny observations, its family dynamics are keenly observed, and Wang is a confident presence behind the camera, playing her intergenerational ensemble off each other and rarely resorting to impassioned speeches to make her points. This is no My Big Fat Greek Wedding–type broad comedy. There’s humor in every scene, but a kind rooted in the unspoken bond between Billi and her grandma (played by Zhou Shuzhen), and the very different connection Billi has with her parents (Tzi Ma and Diana Lin). The indie-studio heavyweight A24 acquired The Farewell for a reported $6 million, possibly setting the stage for the movie to get the sort of wide audience and Oscar success that prior projects like Room, Moonlight, and Lady Bird enjoyed.

The splashiest buy at the festival thus far came from Amazon, which ponied up $13 million for the rights to Nisha Ganatra’s Late Night, a buzzy satire of life in the world of comedy written by and starring Mindy Kaling. She plays Molly Patel, an untested writer who’s hired by the sharp but disaffected talk-show host Katherine Newbury (Emma Thompson) after the program is criticized for not employing female writers. The film is way too stuffed with plot—Newbury is trying to rescue a show in decline, Molly is trying to establish herself, and there are a few unnecessary story twists. But as a Devil Wears Prada–like tale of an intense boss-employee relationship, it works. The movie’s actual joke-writing could be sharper, and at times it feels like Kaling is shying away from really tackling the structural sexism of her industry, inexplicably giving her character an absurd fairy-tale origin story (she’s hired from a job at a chemical plant, rather than from the comedy world). But Thompson’s performance is imperious and cutting enough to keep the whole project afloat.

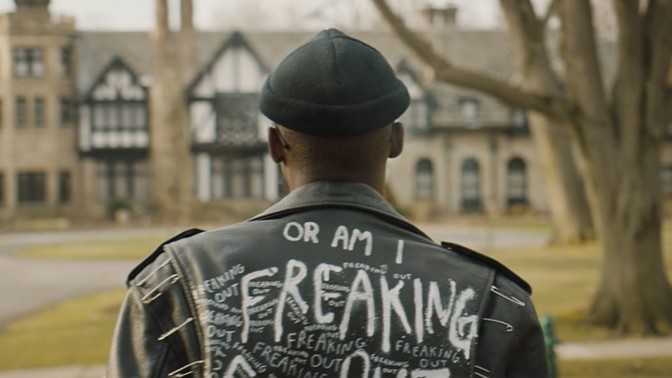

Jonathan Majors and Jimmie Fails in The Last Black Man in San Francisco (A24)

Jonathan Majors and Jimmie Fails in The Last Black Man in San Francisco (A24)For the last few festivals, Netflix and Amazon have scooped up multiple projects at Sundance. But this year, the companies seem to have throttled back, relying more on their own productions. As a result, A24 has been the biggest powerhouse here, screening several movies worth recommending. Chief among them is Joe Talbot’s debut feature The Last Black Man in San Francisco, co-written by and starring his friend Jimmie Fails. The film is a whimsical, sometimes heartbreaking story of how gentrification has swallowed up the duo’s beloved hometown. Fails plays a character based on himself who surreptitiously moves back into his old family home while it stands empty on the market—his way of trying to reclaim a place in a neighborhood he can no longer afford. Talbot supplies painterly visuals and a somewhat abstract storytelling style, while Fails and Jonathan Majors (who plays the protagonist’s best friend) give deftly funny, melancholic performances.

Tom Burke and Honor Swinton-Byrne in The Souvenir (A24)

Tom Burke and Honor Swinton-Byrne in The Souvenir (A24)Another splendid A24 title is The Souvenir, a coming-of-age drama directed by Joanna Hogg, a British filmmaker who has drawn acclaim but little attention overseas for her previous movies Unrelated, Archipelago, and Exhibition (all of which star a young Tom Hiddleston). The Souvenir is based on Hogg’s life in her early 20s—the experience of trying to be a director in 1980s London and falling in love with an older, arrogant, but undeniably compelling man.

Honor Swinton-Byrne (the daughter of Tilda Swinton) is a revelation as Julie, Hogg’s surrogate, while Tom Burke plays her on-again, off-again lover Anthony; Swinton herself contributes a lovely, restrained performance as Julie’s mother. Hogg lets crucial plot information trickle out slowly, and the quieter moments of the couple’s relationship are as important to depict as the big, emotionally harrowing fights. When The Souvenir’s two-hour running time draws to a close, you’ll likely feel as though you’ve lived Julie’s life, painfully and powerfully. A24 will release the film this year, and a sequel, amazingly enough, is set to start shooting this summer.

Ashton Sanders as Bigger Thomas in Native Son (HBO)

Ashton Sanders as Bigger Thomas in Native Son (HBO)HBO snapped up the rights to Rashid Johnson’s Native Son, which was scripted by the acclaimed playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and adapted from Richard Wright’s 1940 novel. Parks has updated the searing tale of Bigger Thomas (Ashton Sanders) for the present, and what’s most compelling about her screenplay is what she’s excised. Though the book’s chief horrifying act of violence remains, other major plot points have been moved around or taken out entirely, in an attempt to account for the way things have changed in the last 79 years.

Certain elements of Wright’s story, which follows a young African American man living in Chicago who accepts a job as a rich businessman’s driver, feel just as relevant now as they did decades ago. In retaining those details, Parks is underlining the enduring, racist inevitabilities of life in Chicago that originally angered Wright. Sanders (who did terrific work in the middle section of Moonlight) is mesmerizing, but the film struggles to keep hold of his character in the final act, as things swerve into irrevocable darkness and what initially felt insightful becomes a bit of a slog.

Annette Bening as Senator Dianne Feinstein in The Report (VICE Studios)

Annette Bening as Senator Dianne Feinstein in The Report (VICE Studios)If Native Son is polemical, then Scott Z. Burns’s The Report is entirely clinical, a thoroughly researched, hard-hitting recounting of the Senate investigation into the Bush administration’s legacy of torture. Burns is a writer who has crafted several candid (but excellent) screenplays for Soderbergh, including The Informant, Contagion, and Side Effects. In his feature-film debut behind the camera, Burns aims to be sober and workmanlike. Adam Driver plays the movie’s deeply effective moral center: Daniel Jones, the real-life researcher who compiled the report for Senator Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening). In doing so, Jones runs into CIA intransigence and hemming and hawing from the Obama administration, the latter of which is represented in the film mostly by Chief of Staff Denis McDonough (Jon Hamm). Nobody gets away clean in this movie, but Burns lets everyone have their say rather than reducing them to cartoon villains (à la Adam McKay’s Vice).

Perhaps the strangest project I’ve seen so far at the festival is Alma Har’el’s Honey Boy, a wrenching drama about a child actor living with his alcoholic father. This actor, Otis (played by Noah Jupe), is an obvious avatar for Shia LaBeouf, who got his start as a Disney Channel star before becoming a blockbuster icon and then spiraling into substance abuse and depression. The personal connection is clear because LaBeouf wrote the screenplay, and because he plays the character based on his own father, a former rodeo clown with a stringy, receding mane. In flash-forwards to the present, Lucas Hedges plays an older Otis, reckoning with his father’s abuse. The whole experience is akin to being in therapy with LaBeouf as he works through major revelations. Har’el (an obvious talent) translates close-to-the-bone emotional content into a stark vision of life balanced on a knife-edge, with just enough humor and heart to keep things from feeling too miserable.

As for the rest of the festival, there will be premieres for Netflix’s gonzo art thriller Velvet Buzzsaw, Chinonye Chukwu’s much hyped prison drama Clemency with Alfre Woodard, the Lupita Nyong’o–starring dark comedy Little Monsters, and the oddball comedy Brittany Runs a Marathon. Studios will also start to settle on their major acquisitions, and the competition prizes will be awarded, firing the starting pistol on 2019’s movie season many months before next year’s Oscars are on anyone’s mind.

Efforts to find remaining survivors have ramped up in towns devastated by the collapse of a huge dam, which released a torrent of muddy iron-ore waste in Southeast Brazil. On Friday, the dam, owned by the Brazilian mining company Vale, collapsed near the town of Brumadinho, sending tons of sludge down into the valley below, damaging or destroying houses, farms, and vehicles. Authorities have reported at least 60 deaths, with another 290 people still listed as missing—and warnings have been issued about another dam nearby that is also at risk of failure.

The Starbucks founder Howard Schultz is the Twitter villain of the hour. If hot takes actually generated heat, Schultz would already have been vaporized under the onrush of magma. His offense: contemplating a run for president as a self-funded independent centrist.

Many people could raise a legitimate complaint against this expensive plan, starting with Schultz’s heirs. But the Twitter complaints arise from concern not that Schultz is about to waste his money, but that he might spend it effectively. He might weaken the Democratic candidate in 2020, and thereby help reelect President Donald Trump.

Actually, this complaint reveals why Schultz’s exploration is just the help America needs. Schultz seems to intend to run as a compassionate businessman concerned that the Democratic Party is veering too far to the left. In an interview on CBS’s 60 Minutes, he complained of promises of free health care and free college tuition.

[Read: Ex–Starbucks CEO could get Trump elected]

These complaints have been mocked as the selfish preoccupations of the superrich. If that were true, however, Democratic activists would have no reason to fear Schultz’s candidacy. America’s new progressive majority could roll right over Schultz’s plutocratic message.

The trouble is that, while there is clearly a strong anti-Trump majority in America, that majority is not so progressive. The crucial final piece of the anti-Trump coalition—the difference between 2016 and 2018—is that Trump has alienated a lot of people, especially women, who normally vote Republican.

College-educated, comparatively affluent, fiscally concerned: These are the voters who delivered George H. W. Bush’s former congressional seat in Houston to a business-minded Democratic candidate, Lizzie Fletcher. These are also the voters who balked the hopes of Andrew Gillum in Florida and Stacey Abrams in Georgia. They are not a majority either, nothing like it, but they are indispensable to defeating Trump. And whether or not they would ever actually vote for Howard Schultz, they are nodding along to his words.

The early Democratic presidential contest has been an exercise of lefter-than-thou politics, culminating in the earnest consideration of 70 percent tax rates and wealth confiscation for émigrés.

[Read: 10 new factors that will shape the 2020 Democratic primary]

You can understand the temptation: Trump seems weak, perhaps already doomed. Why compromise with the faint of heart? Give the American people a choice, not an echo!

This is the logic of factional politics. You want the smallest possible majority, most easily dominated by its most mobilized minority. That’s how the Tea Party thought during the Obama years, that’s how the Trump campaign evolved in 2016. Sometimes it can work, at least if you catch a lucky bounce.

But if you seriously believe that the Trump presidency presents a unique threat to American democracy, you want the safer choice, not the risky one. You want the candidate with the broadest possible appeal, not the most sectarian. Trump will be beaten not by his fiercest enemies, but by his softest supporters. You want to appeal to them, detach them—not chatter on social media about how you’d like to punch their kids in the face.

I have no idea whether Schultz can accomplish that mission. Probably not. But if Schultz at least delivers a timely reminder that somebody must accomplish that mission—and that Democratic self-indulgence will be Trump’s most indispensable resource in 2020—then he will have served his country well.

Several years ago, a couple from Twitter contacted Star Ritchey with a request: They wanted permission to put her name in their will. Ritchey had never met the couple before, but they wanted her to inherit their dogs.

“They don’t have kids, but they have bulldogs, and they reached out and said, ‘If something happens to us, we don’t know what would happen to them,’” Ritchey told me. “They said they knew that even if I couldn’t keep them, I’d get them to a good rescue.” The couple had decided Ritchey was right for the job because of her favorite hobby, which is posting about her own beloved bulldogs—the Frenchies Emmy and Luna—on Twitter.

After Ritchey started her Twitter account in 2013 as a fun way to occasionally tell the world how much she loved her previous dog, the English bulldog Georgia, she quickly got pulled into a realm of social media she didn’t know existed: bulldog Twitter. There people bond over their shared devotion to their dogs, share pictures and stories, and often meet in real life. Posting from her dog’s account quickly became a normal part of Ritchey’s day.

Then, in 2016, her relationship to that social-media circle evolved from simple fun to something deeper: Georgia was diagnosed with cancer. Ritchey had to navigate new emotional terrain with people who normally wouldn’t be involved.

[Read: How dogs make friends for their humans]

Posting enough about your pet that strangers become emotionally invested in them might seem a bit absurd, but as the barrier between online and offline life vanishes, it’s only natural that more elements of people’s emotional lives begin to migrate to digital spaces. Even for those who don’t maintain accounts specifically dedicated to their pets, a world in which our lives are more public and interconnected than ever presents a challenge. What should you share as your pet’s health inevitably starts to deteriorate, and what happens when you tell thousands of people that something you love is dying?

The best-known version of digital pet cosplay happens on Instagram, where the visual nature of the platform helps some particularly cute and well-photographed pups rise to fame beyond their roles as adored family pets. Dorie Herman is the steward of one such clan of pups, the Kardoggians. She started out with Chloe, who passed away last year, and now she has Cupid and Kimchi—three senior rescue Chihuahuas with a following of 161,000 people.

When you have an older dog, medical problems come with the territory, but that doesn’t make them any easier to share. “When something’s wrong with [your pet], it forces you to say it out loud, which makes it a little too real sometimes,” says Herman. In addition to the well-being of her pets, she worries about how their health affects the strangers who are emotionally invested in them. “If I don’t know what’s going on, I don’t want to worry them, or for people to feel like I’m manipulating their emotions,” Herman says. She’s careful to wait until she has concrete information from her veterinarian before saying anything publicly.

Once Herman began to post about Chloe’s medical problems, people on Instagram who loved her dogs gave her an incredible amount of comfort. “I’ve never felt more surrounded by love and care,” she says. Although it’s been months since Chloe’s death, fans are still grieving with Herman. “People reach out and ask me how I am, and tell me they were looking at pictures of her and missing her,” she says, which makes her own grief less isolating. “I can talk about my dog to so many people who actually know who she was and loved her the way I loved her.”

Hilary Sloan, the dog mom to the Bean family of Instagram-famous rescue pups (and a former co-worker of mine), sees her dogs’ health problems as a way to educate her six-figure following about their own pets’ health. “I have a lot of access, and that’s the privilege of my platform,” she says. “I wouldn’t hoard that knowledge—that’s not who I am as a person. I love dogs.”

She and her husband recently lost Louis, an elderly Cavalier King Charles spaniel who rarely appeared on her account (he didn’t like dressing up, Sloan says). The couple experienced the same outpouring of support Herman did when Chloe died. Now the family is treating 11-year-old Ella Bean for thyroid problems and adding frequent posts about pet health, including videos from vet checkups and live Q&As about things such as doggie CBD and acupuncture. “I chose to share Ella’s condition because maybe someone else will notice their dog changed,” Sloan says. “Maybe they’ll do what I did and get blood work right away instead of waiting.” (Ella is doing great, if you’re worried.)

But you don’t have to own a bona fide furry influencer for the internet to rush to your aid in pet tragedy. When Georgia was sick, Ritchey, the bulldog owner, decided to share what her family was going through with her friends on Bulldog Twitter—her dogs have a few thousand followers—and she was overwhelmed by the depth of support she received. “Even my husband, who doesn’t do their social-media stuff, would sit for hours and read through these messages,” she says. The outpouring wasn’t limited to tweets. “We had more flowers sent to our house than you could imagine. People were going to Mass, doing things for her at their church,” says Ritchey.

[Read: The movement to bury pets alongside people]

Lisa Lippman, the lead veterinarian for Fuzzy Pet Health in New York City, thinks sharing an aging pet’s health struggles online is a good impulse that can help viewers be vigilant about their own pets’ health. Seeing someone, whether a friend or influencer, guide a pet through medical treatment on social media can make it easier for people to identify problems in their own animals. “A lot of people start to say, ‘Oh, they’re slowing down,’ or ‘[They] aren’t their old selves,’” she says. “Often we can attribute those things: It’s not old age; it’s arthritis or some other ailment that we can treat, if we know about it and if people visit their vets.”

No one wants to contend with a loved one’s mortality or give people bad news, but in a community built around short life spans, the promise of eventual grief is the price of entry for loving an animal, even if it’s not your own. “We have cried over so many dogs we’ve never met in the past five or six years,” says Ritchey. Maybe in that shared experience of decline and loss, people find it a little easier to lean on one another. Georgia may have passed away, says Ritchey, but she lives on in the friends Ritchey made because of her, such as the couple who included her in their will: “She was just a little bulldog who was our world, but somehow she meant a lot to everyone else, too.”

As trade talks between the United States and China resume this week, there is optimism that the world’s two largest economies can reach a deal to end their destabilizing dispute: With the Chinese economy slowing and President Donald Trump in need of some good political news, both sides face pressure to compromise. A settlement, if it happens, would probably calm jittery investors and remove some economic uncertainty.