The partial U.S.-government shutdown continues, while the House Democrats push forward with the establishment of a Climate Crisis Committee—to the disappointment of some activists on the party’s left, who’d hoped for a more ambitious mandate. Still at loose ends is the fallout over the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi’s murder, the geopolitical impact—or lack thereof—of the withdrawal of troops from Syria, how the push for greater gun-control regulation, reignited in 2018 after another fatal year, will continue to unfold, and much more. And what will President Donald Trump confront in the new year, halfway through his first term?

The Daily will be on a break until January 2, 2019, so we leave you here with a few more stories from this past year to catch up on. Happy new year.

The New York City sky turns bright blue after an explosion in the borough of Queens on December 27, 2018. See the other most striking photos from around the world this week. (Photo by Melissa Coffey via Reuters)What to Read

The New York City sky turns bright blue after an explosion in the borough of Queens on December 27, 2018. See the other most striking photos from around the world this week. (Photo by Melissa Coffey via Reuters)What to ReadFinding a way through an unspeakable loss (Deborah Copaken)

“The other mothers from our playgroup were at the funeral as well, all of us with the same guilty thoughts: Why did we still have our children when Suzi did not? It felt wrong, obscene. ‘It’s incomprehensible,’ we kept saying to one another, for lack of better words. ” → Read on.

I know Brett Kavanaugh, but I wouldn’t confirm him (Benjamin Wittes)

“If I were a senator, I would not vote to confirm Brett Kavanaugh. These are words I write with no pleasure, but with deep sadness. Unlike many people who will read them with glee—as validating preexisting political, philosophical, or jurisprudential opposition to Kavanaugh’s nomination—I have no hostility to or particular fear of conservative jurisprudence.” → Read on.

The humiliation of Aziz Ansari (Caitlin Flanagan)

“I thought it would take a little longer for the hit squad of privileged young white women to open fire on brown-skinned men. ” → Read on.

Hippos poop so much that sometimes all the fish die (Ed Yong)

“Every day, the 4,000 or so hippos in the Mara deposit about 8,500 kilograms of waste into a stretch of river that’s just 100 kilometers long.” → Read on.

Illustration by Lisk Feng

Illustration by Lisk FengThe bullet in my arm (Elaina Plott)

“I stroked my mother’s hair as she cried and drove me to the hospital. The surgeon said the bullet was small, maybe a .22-caliber, and too deep in the muscle to take out, so it’s still in my arm. They never caught the shooter, or came up with a motive.” → Read on.

Why rich kids are so good at the infamous marshmallow test (Jessica McCrory Calarco)

“A child’s capacity to hold out for a second marshmallow is shaped in large part by a child’s social and economic background—and, in turn, that that background, not the ability to delay gratification, is what’s behind kids’ long-term success.” → Read on.

More and more Americans are reporting near-constant cannabis use, as legalization forges ahead (Annie Lowrey)

“‘Part of how legalization was sold was with this assumption that there was no harm, in reaction to the message that everyone has smoked marijuana was going to ruin their whole life.’” → Read on.

Amazon’s HQ2 spectacle isn’t just shameful—it should be illegal (Derek Thompson)

“Why the hell are U.S. cities spending tens of billions of dollars to steal jobs from one another in the first place?” → Read on.

Why do cartoon villains speak in foreign accents? (Isabel Fattal)

“The common denominator in all of these vague foreign accents is ‘the binary distinction of “like us” versus “not like us.”’ ‘Villainy is marked just by sounding different.’” → Read on.

This special edition of the Daily was compiled by Shan Wang. Concerns, comments, questions? Email swang@theatlantic.com

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for the daily email here.

With a flash, the sky over New York City turned a mystical blue.

The spectacle, which appeared without warning on Thursday night, stunned observers. They sensed something was wrong—because, obviously, would you look at the freaking sky?—and quickly formulated some possible explanations. The theories leaned heavily on science fiction. Maybe the glow signaled the end of a massive battle between superheroes. Maybe it was an alien invasion. Maybe the apocalypse was nigh, and this, these eerie turquoise clouds over Queens, were the first sign that the end was near.

What people witnessed was much less dire: a quirk of electricity. Just after 9 p.m. local time, some equipment at an electrical power plant in the Astoria neighborhood short-circuited. (There was no explosion or fire, contrary to early reports.) According to the station’s operator, Con Edison, the malfunction produced something called an arc flash. A powerful electric current shot into the air and sent atoms of gas in the air into a state of excitement. When atoms become excited, they emit light, and different gases produce different colors. In this case, the atmospheric recipe created for a ghostly blue.

“No injuries, no fire, no evidence of extraterrestrial activity,” the New York Police Department tweeted, extinguishing most of the theories that had flooded social media.

Sorry to disappoint, but the eerie blue glow last night wasn’t an alien invasion. 🤷♂️👽 Our live #EarthCam in midtown #NYC captured the electrical arc flash as it turned the night sky blue! pic.twitter.com/3fY56xu1ug

— EarthCam (@EarthCam) December 28, 2018It was a joy to watch the discussion of the blue light unfold online. This strange December night encapsulated so much of what makes the internet great: the dissemination of captivating photos and videos in real time, a shared sense of camaraderie that transcends state lines and borders, and some pretty funny jokes. But the evening also tapped into something much older and more primal. We human beings have long been intrigued by strange lights in the sky. Like the blue glow over New York, these sights have baffled, scared, and mesmerized us, even when we’ve known their source.

Perhaps the oldest example is the aurora borealis, the resplendent performance of dancing lights in the night sky. Today, we know the northern lights are the product of electrons from the sun interacting with different gases in Earth’s atmosphere. But centuries ago, observers, captivated by the wisps of colors, dreamed up their own explanations. In ancient China and Europe, the auroras were dragons and serpents, flitting around in the night. In Scandinavian folklore, they were the burning archway that allowed gods to move between heaven and Earth. During the American Civil War, soldiers thought the lights were a sign of disapproval from God to the Confederacy.

[Read: Canadian amateurs discovered a new kind of aurora]

During at least one time in history, the sight of weird lights in the sky became a business opportunity. Starting in the early 1950s, during the height of the Cold War, the United States government detonated thousands of atomic bombs in the Nevada desert, illuminating the sky with bright flashes. The city of Las Vegas, located just 65 miles away, saw lucrative potential in the morbid spectacle, and decided to monetize the mushroom clouds. As Laura Bliss wrote in a 2014 CityLab story:

The Chamber of Commerce printed up calendars advertising detonation times and the best spots for watching. Casinos like Binion’s Horseshoe and the Desert Inn flaunted their north-facing vistas, offering special “atomic cocktails” and “Dawn Bomb Parties,” where crowds danced and quaffed until a flash lit the sky. Women decked out as mushroom clouds vied for the “Miss Atomic Energy” crown at the Sands. “The best thing to happen to Vegas was the Atomic Bomb,” one gambling magnate declared.

Spectators knew what they were looking at, but they were still astonished—excited and frightened at the same time. “People were fascinated by the clouds, by this idea of unlocking secrets of atom,” Allen Palmer, then the executive director of the National Atomic Testing Museum, told CityLab. “But there was absolutely an underlying fear—we were so close by.”

[Read: How the world learned about the Pentagon’s sky-high nuclear testing]

In other cases, a shroud of mystery can heighten those feelings. Around the same time tourists in Las Vegas were watching nuclear explosions bloom, Americans on the other side of the country were enthralled by a different kind of light in the sky. On a summer day in 1952, multiple people in the Washington, D.C., area reported spotting several unearthly points of light traveling over the landscape. One commercial pilot described them as “falling stars without tails.” When they approached the White House, the military summoned a pair of jets to intercept the unknown flyers, but no mystery invaders were found.

The next day, the news of the moving objects was all over the news. Headlines suggested, in capital letters, that the objects were extraterrestrial. Government officials, stumped themselves, didn’t exactly try to quash the rumors. According to The Washington Post, an unnamed Air Force source told reporters: “We have no evidence they are flying saucers. Conversely we have no evidence they are not flying saucers. We don’t know what they are.”

Unidentified flying objects have maintained this allure for decades. As recently as 2012, the Pentagon was operating a program to investigate reports of UFOs. When The New York Times broke the story in late 2017, it proved to be full of the hallmarks of a timeless mystery—surprise, suspense, wonder.

The blue lights over New York were a good mystery, too. The unnatural glow eventually dimmed and the sky returned to its usual evening hue. Con Edison resumed normal operations. People went on with their lives. But for a brief time, they were engaged in a long-standing tradition: trying to make sense, together, of something strange in the sky.

Two writers took the time to remember loved ones who died this December. The Atlantic staff writer Franklin Foer wrote a tribute to his grandmother, Ethel, who as a teenager trekked 2,600 miles to flee Nazi persecution with nothing but a pair of scissors and a winter coat. He remembers her as a woman who loved life fiercely: “Survival, in the end, feels like an insufficient word to explain her existence. To survive is to keep on breathing … To be a survivor is to emphasize toughness. Her essence was sweetness.”

The Atlantic contributing writer Deborah Copaken wrote in memory of her close friend’s 23-year-old daughter, Maddy, who died suddenly in a car accident on December 14. She recounts her memories of seeing Maddy grow up, go to college, and fall in love, and the inconceivability of her passing. “We can’t go on. We must go on,” she writes. “We can’t process the death of a child. We must speak of it anyway.”

HighlightsThe practice of paying children an allowance has been around for about a century, often providing an incentive for children to complete household chores. But as the Atlantic staff writer Joe Pinsker notes, it can send kids counterproductive messages about their responsibility to their family, especially for middle- and upper-class children.

We asked Atlantic readers to write in with their family’s unusual winter holiday traditions, and commissioned illustrations of our favorite stories based on their family photos. Here’s a sample from our picks.

Dan Bransfield

Dan Bransfield“We follow an old-world, European tradition of giving our cows hay on Christmas Eve. The origin of the tradition is that because cows protected and kept Baby Jesus warm when he was born in a stable, we need to honor them by feeding them the best hay that we have.” — Steve Schwanebeck

Dan Bransfield

Dan Bransfield“In my family, we have a tradition of camping out and having a slumber party under the Christmas tree on Christmas Eve every year ... We’re not sure how this started, but it’s possible that we wanted to be closer to the tree and the presents on Christmas morning and probably didn’t want the festivities to end. Now my siblings and I are adults, but we share this sleepover tradition with our nieces and nephews.” — Amanda Hopkins

Dear TherapistEvery Monday, the psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb answers readers’ questions about life’s trials and tribulations, big or small, in The Atlantic’s “Dear Therapist” column.

This week, a reader asks how to talk about finances with her boyfriend—specifically, how his wealthy parents share their money. She feels jealous of his twin brother’s wife, whose living expenses are partially paid for by his parents, but she isn’t sure if she should bring it up with her boyfriend.

Lori’s advice: Have a conversation about money with your boyfriend, and try to figure out what’s lying beneath the envy.

Money can signify so many things: love, acceptance, commitment, safety. It may be that getting financial support from your boyfriend would make you feel loved and valued by him ... Or perhaps having his parents’ support would make you feel more accepted by them as a future member of the family, or give you a stronger sense of commitment from your boyfriend.

Send Lori your questions at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Strange blue lights in the night sky over New York, Christmas calls from the White House, a fox hunt in Ireland, icy weather in China, the Sahara Festival in Tunisia, Santa Claus on Copacabana Beach in Rio, recovery from a tsunami in Indonesia, an eruption of Mount Etna in Sicily, penguins in Italy and Antarctica, and much more.

On the morning of December 26, Alan Meloy stood on the front porch of his home in northern England and noticed that “murky” early clouds were clearing into a crisp and sunny winter’s day.

Meloy, a retired IT professional and a plane spotter of 45 years, decided to grab his best camera to see whether he could catch any interesting flyovers. Before long, he saw a “jumbo”—a Boeing VC-25A—and, knowing there were few such aircraft left, took about 20 photos of the plane. He could tell immediately that there was something unusual about it, though.

“It was just so shiny,” he told me. As it turned out, Meloy had unwittingly captured Air Force One.

Meloy’s photo, which he uploaded to the image-sharing service Flickr, provided the confirmation a group of hobbyists needed to outwit the security precautions of the world’s largest superpower transporting its leader on a secret trip to a conflict zone. In effect, President Donald Trump’s visit to a U.S. military base in Iraq the day after Christmas was publicly known among a band of enthusiasts even before he landed in the country.

[Read: The president is visiting troops in Iraq. To what end?]

The incident is just the latest in a long line in which hobbyists, hackers, or armchair internet detectives have outwitted or thwarted the best intentions of governments, secret services, and militaries, a reminder of how the connected world opens all of them to new, evolving threats—and how unprepared even the world’s most advanced governments are to deal with the simplest of these threats.

Trump is not the first world leader to run into such issues. Britain has faced its own set of headaches with the tracking of planes.

Last year, when Prime Minister Theresa May traveled to meet the newly inaugurated U.S. president, a journalist noticed that her plane was being tracked online. At the time, Jim Waterson, then the politics editor at BuzzFeed’s British operation, tweeted that the Royal Air Force refueling craft that doubles as May’s executive transport plane could be tracked on FlightRadar and similar flight-tracking websites. “No one on the trip raised a complaint when I tweeted this,” said Waterson, now at The Guardian. Weeks later, though, The Mail on Sunday, a British newspaper, claimed that the fact that the plane could be tracked left open the possibility of, as Waterson described it, “terrorists potentially—with the emphasis on potentially—being able to use this information to shoot the prime minister out of the sky.” May’s plane is now no longer trackable on most consumer websites.

Still more embarrassment for the British government came in the form of another Mail on Sunday story, this time noting that a U.K. spy plane, reportedly flying a U.S.-U.K. operation scouting Russia’s air defenses, was also trackable by plane-spotting apps.

Regardless of who is aboard a plane, stopping people from tracking its location is not entirely straightforward: Crossing crowded airspace over multiple countries requires a transponder to be sending information on the aircraft’s location, call sign, and similar details (Air Force One’s disguised call sign on Trump’s Iraq trip, for the record, was RCH358). That does mean that in the new, far more connected online world, there will always be a form of risk.

[Read: How Twitter is changing modern warfare]

Plane spotters such as Meloy have been watching out for aircraft for decades, but as David Cenciotti, a respected aviation blogger, notes, new technical tools at their disposal, along with the near-instantaneous communications afforded by the internet, have changed the dynamic. “You are crowdsourcing something that 20 years ago would require weeks of investigations and letters exchanged with other geeks,” Cenciotti told me.

In other words, whereas once Meloy’s photo might have been an item of curiosity in a plane-spotting magazine a month after the fact, it now allows the president’s plane to be tracked in real time.

In fact, Cenciotti noted, military aircraft are fitted with the same transponders as civilian ones, and on occasion the operators of the military aircraft have forgotten to turn off the transponders during operations—including in Syria. This has been flagged as a real “operations security risk” in a report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, increasing the risk of warning an adversary of an impending strike or even of allowing an attack to be intercepted. In the case of Air Force One this past week, Cenciotti said that because it was traveling through multiple countries’ airspace, it could not simply turn off its transponder (though he suggested it could have flown a different route or, to make sighting it harder for plane spotters, flown at night).

Planes are just the most obvious area in which the worlds of government and security services connect with civilians and hobbyists in potentially dangerous ways. Another is the world of cybersecurity, where nation-states, criminal hackers, and enthusiasts can interact.

Take the hack that became known as WannaCry: Exploits and hacking tools discovered by the National Security Agency were stolen and posted online. Several of these tools were modified into a devastating ransomware attack, which effectively held a computer hostage unless the victim paid a ransom. That particular attack began in Ukraine, but soon spread much farther, infecting, among others, Britain’s National Health Service, where it did more than $100 million worth of damage. And then, once in the wild, it was modified for commercial purposes by criminal hackers and used to extort still more victims.

These are hardly isolated examples, and it’s not only Western countries that have found themselves on the wrong end of such efforts: The open-source intelligence outlet Bellingcat has built its entire website on the basis of using openly available information to expose truths and counter misinformation, including using mapping information and satellite imagery to get to the bottom of attacks in both Ukraine and Syria.

The era of spy versus spy—if it ever truly existed—has certainly been ended by the internet. Today it is spy versus tweeter, plane spotter, criminal, activist, journalist, bored teenage hacker, and who knows who else. Many will intend no harm, and most breaches, such as the revelation of President Trump’s flight, will prove harmless.

But neither good intentions nor the fact that most breaches end up being inconsequential matters. The risks are real, and the signs don’t suggest that even the world’s largest superpower is ready to take the issue seriously, not least because it can’t seem to resolve even the simplest of problems: making the president’s plane hard to track.

I can’t write this story. I must write this story. My brain can’t process this story, though this story has been my brain’s main occupant since the morning of December 14th, when I heard the news.

Where to begin? With the accident itself? With the sludge of hours and days that followed? With the snow, the patch of ice, the oncoming headlights, none of which I saw in real life but all of which I now see at least once a day, in painful slow motion?

No, let’s back it up further. Way back, to the beginning, when my colleague Roberta walked into my office in Rockefeller Center and said, “I have a friend I think you should meet. She’s due right around the time you are. You guys can hang out on maternity leave!” This was 1995, when I was pregnant with my first child. We had no cellphones, no email. Just phone numbers stored in Filofaxes or in our head. “Here,” said Roberta, handing me a scrap of paper with the word Suzi on it followed by a phone number.

I feigned interest. Why would I want to hang out with a friend of a friend, just because our babies were due within weeks of each other? I smiled at Roberta and thanked her. The minute she walked out of my office, I threw the scrap away. I was busy, trying to tie up loose ends before my baby was born.

Jacob arrived two weeks early. Suzi’s baby, Madeline, hit her due date precisely. Or so I heard from Roberta, who would not be dissuaded by our lack of interest in meeting each other. A few weeks after Maddy was born, Roberta invited Suzi and me and our newborn infants to her apartment for brunch.

Suzi and I hit it off immediately, after she told me she’d tossed my number in the trash as well, and we spent not only most of our maternity leaves together, but the next 23 years. We started a music playgroup for our kids, because who wants to pay to have someone else sing “Baby Beluga” to a baby? If you know C, D, G, E minor, A, and D7, you can pretty much play any baby song ever written.

For five years, playgroup took place every Monday after work in the basement playroom of my building. After playgroup, Suzi, her husband, Franklin, Maddy, and eventually Maddy’s baby brother, Alex, would come upstairs to my apartment, where I would make us all dinner. Nothing fancy, just kid fare: mac and cheese, chicken, and one time linguine with shrimp, to the delight of Maddy, who liked to wander into the kitchen, compliment my bland cooking, and ask questions. Lots of them.

Why was the kitchen floor, in the summer, too hot for bare feet? (Because our first-floor kitchen was above a parking garage, which would overheat every July.) Could she take out the watercolors and paint? (Yes. Of course.) Could you use a toaster oven to cook chicken? (Theoretically, yes. Let’s try it and see.) Where was my husband? (At work.) But you work, and you’re here. Why? (It’s complicated, sweetheart. When you’re old enough, we’ll talk about patriarchal power structures and the plight of working mothers.)

[Read: The secret life of grief]

After my separation from my husband, when Maddy was starting her last year of boarding school, where she’d become a master at the pottery wheel, and Jacob was starting his first year of college—my son was born on May 28th, making him one of the youngest in his class; Maddy was born on July 14th, making her one of the oldest in hers—Suzi and I met for lunch at Whole Foods, and she held me as I disintegrated into pieces. “How do I even do this?” I sobbed.

“One step at a time,” she said.

I was reminded of the time Maddy and Jacob were both turning 3, or maybe it was their fourth birthday, who knows, but what I do recall is that we took the kids to the Central Park Zoo to celebrate. As we meandered our way there, the way Olmsted intended, Maddy insisted on climbing every rock along the way. Jacob stood a safe distance below, delighting in Maddy’s courage but firmly grounded by his lack of it.

“Come up! Climb with me, Jacob!” she said. When he did not budge, she climbed back down and said, “It’s not scary. I promise. Here, I’ll help you.” She grabbed his hand and led him up, one step at a time, to the top of a tall rock, showing him the beauty of life’s vista from her fearless vantage point. Maddy was that kid. The kid who drank up the world on her own terms. The kid with the unusually mature inner calm and a constant smile, as if she understood the absurdity of it all from toddlerhood on. The kid who was never on time, because why rush life when you can stop and not only smell the roses but feel the softness of their petals against your skin and then turn them into an ephemeral art project? The kid who refused to wear a coat in the winter not because she was stubborn but because she liked the feeling of cold air on her skin.

Suzi and Franklin, to their credit, never forced her to be anyone she wasn’t. They knew if she got cold enough, she’d put on a coat. That if they insisted she be on time, she would never have time to notice everything and then translate that into solid form.

Jacob recently ran into her at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) while visiting a friend. “We had such a nice time,” he said. “She’s so cool.” Maddy was studying painting, having turned her love of pottery into a mixed-medium form of two-dimensional representation. I guess you’d call it 2-D 3-D, since she used a 3-D printer to create tiny images on tiles of, say, Halloween scenes or faces, which she would then mix in with more abstract tiles and turn them into mosaics. In other words, Maddy was still being Maddy, unable to pin down with even the normal nomenclature of art.

This past September, she fell in love. She and her girlfriend insisted that both of their families have Thanksgiving dinner together, which they did, to the delight of all present. Maddy was finishing up her thesis, but the two had decided that she would stay at RISD for another year and a half so they could live together while her girlfriend, still a junior, finished up.

When I spoke to Suzi on the morning of December 14th, a few days after Maddy had finished her senior thesis, the organ harvesters had just arrived. The previous night, Maddy and her girlfriend had been driving from New York to Bennington to help Franklin pick up Alex from college. Franklin had been in the car ahead. At some point he realized that he no longer saw his daughter’s car behind him, and, growing concerned, he turned around. He found Maddy trapped in the driver’s seat. He held her in his arms, alive but unconscious, until the ambulance arrived. Her wheels had slipped on a patch of ice, sending her car into an oncoming truck. Her girlfriend walked away bruised but otherwise physically unscathed. Maddy died at the hospital on the operating table a few hours later.

[Read: The first holiday without a loved one]

“I’m going to need help getting through this,” Suzi said to me. I told her I’d be there as fast as I could. We’d take it one step at a time. Three hours later, I walked into their house in Hillsdale, New York. The first person I saw was Selma, Suzi’s mother, her head hung unusually low. “It’s unreal,” she said. “Unnatural.” I agreed. The fabric of the universe is irreversibly torn when a granddaughter leaves this earth before her grandmother. Franklin was slumped on a couch in the living room, staring out at the four empty chairs on the patio and to the mountains beyond. Everything in me wanted to run outside and remove one of the chairs from view, as if carting off a physical metaphor for their loss could ever ease the forever pain of it.

Our friend Helen walked in, crying, followed by Suzi and Alex, who’d been on a hike after arriving home from the hospital. I hugged Suzi, who, still in shock, spoke of the eerie calmness in the hospital room the night prior, as if Maddy were still there, sprinkling her never-in-a-rush essence over them. “I’ve always joked,” she said, “that the only time Maddy was ever on time was her due date. Now, for the first time, she’s early.” Alex hugged a family friend and wailed, a long, guttural moan of such pain and endurance that it will haunt all of us who heard it for years to come.

Selma, with all of her aged wisdom, kept looking for some meaning to make sense of it. “It must have been bashert,” she said, using the Yiddish word for destiny. As if it were God’s plan to take Maddy from us too soon. “I can’t believe that,” I said, having long ago decided that life is random chaos and pain, from which beauty must be sought out and appreciated every day to make it less so.

The last time I saw Maddy was this past July, when I was seated across from her at a large and lively dinner around her family’s table. Between the main course and dessert, my WeCroak app dinged, as it does every day, five times a day, with a friendly, “Don’t forget, you’re going to die.” The app was created out of a Bhutanese maxim, which asserts that contemplating death five times a day brings happiness. I downloaded it onto my phone after a near-death experience the previous summer. Maddy laughed when I explained all of this to her. “I don’t need an app to remind myself I’m going to die,” she said. “I’m aware of it every second.” She’d also made her peace with it, she said. She recently told her family that she had a premonition she would die young. She wanted them to understand that she was not scared of this, should it come to pass. “Tell Jacob I said hi,” she said, as she got in her car that night. “We had a really nice talk recently.”

“I heard,” I said. “I’ll tell him.”

Jacob and I stopped for lunch at a diner on the way to Maddy’s funeral, where a hawk would stream across the sky, in full view of the mourners, at the moment the rabbi read a prayer about flight. My son told me about Heidegger’s views on death and the importance of understanding nonexistence as an integral part of existence, and in that moment, taking a bite of my food and a sip of water, which is what living people must do to keep going, I had two radically conflicting, albeit Heideggerian, thoughts: I’m enjoying this moment of conversation and sustenance with my grown child so much, and I feel guilty for enjoying this moment of conversation and sustenance with my grown child so much.

The other mothers from our playgroup were at the funeral as well, all of us with the same guilty thoughts: Why did we still have our children when Suzi did not? It felt wrong, obscene. “It’s incomprehensible,” we kept saying to one another, for lack of better words. Roberta, of course, was there as well. I hadn’t seen her in years, as she moved away long ago, but we clung to each other and sobbed. “Thank you,” I belatedly said, “for introducing me to Suzi.” Had she never done so, I would have missed out on 23 years of having the privilege of knowing Maddy Parrasch.

Maddy’s ashes, true to her corporeal form, were late to arrive, so we didn’t get to scatter them at the funeral. I went back up to Hillsdale three days later, on Suzi’s birthday, to help her try to celebrate amidst her grief. While Franklin prepared his wife’s birthday feast—as great an act of love as I’ve ever witnessed—Suzi, Alex, a family friend, and I embarked on an hour-long hike up a Berkshire mountain, arriving at the top exactly a week after Maddy’s death. We hadn’t planned on this coincidence of timing. In fact, we were a few hours late getting started and worried about it growing dark during our descent, but we were determined to get Suzi out of the house and into nature. Knowing Maddy and her love of Central Park rock climbing and vista gazing, knowing her acceptance of her own mortality, even at 23, she would have loved (we decided for her in absentia, standing there at the summit) the synchronicity of celebrating her mother’s birth and her last breath at the top of a mountain named Monument.

“L’chaim,” Suzi said, blowing out her candles later that night—to life. Because what other choice do we humans, still with breath, have? We can’t go on. We must go on. We can’t process the death of a child. We must speak of it anyway.

There were the scissors that my grandmother somehow remembered to bring with her as she fled. She could hear the rumble of destruction in the distance. She could see the cloud of smoke that was the Nazi murder of her family and neighbors. Without forethought, she made the decision to run ahead, carrying with her the scissors and, despite the blossoms of spring, a winter coat.

In the seasons that followed, which piled into years, she kept on walking, from Poland to Uzbekistan, and then back again. Although she was a teenager, her body could barely sustain the 2,600-mile trek. Her legs would swell, and sores covered her trunk. She nourished herself with stolen potatoes, expertly hidden in the lining of her dress. When she came into the occasional possession of grains of rice, she saved them as if they were precious metals.

For decades, she said nothing about her escape. Then she gathered the courage to recite the story to her grandchildren, and she found that it fortified her against her nightmares. Narrating her life provided a sense of meaning to the improbability and pain of survival.

By the time I reached fifth grade, the scissors and the coat had become the foundational tale of my family’s existence. The small Jewish woman who turned her basement into a well-stocked bunker filled with enough bags of flour and boxes of Rice Krispies to withstand the next catastrophe emerged as our superhero. Her life was a testament to cunning, courage, and contingency. When I think about the scissors and the coat, it’s hard not to also think of the mountain of worn shoes at the Holocaust Memorial Museum, or the television clip that pauses to show the eyes of the child migrant. It’s hard not to think about the bare margin that separates survival from death, the decision made in a flicker that accounts for existence.

[Read: A son’s quest to find the man who saved his parents’ lives during World War II]

Her life connected ours to tragedy and history. I have piles of cassettes, compiled while sitting with her as she recounted her biography at her faux-marble kitchen table, sipping instant coffee from a red mug. She died 10 days ago. Now we no longer have her witness—in a time when Jews are slaughtered in Pittsburgh, when anti-Semites have regained power in the old blood-lands of Europe. My grandmother has become a memory, at a moment when the memory of the destruction of Jewry seems too faint to restrain the return of animal hatreds.

But right now, history feels small in comparison to the example she provided of how to suffer and to love. For some reason, I have in my head the story of what happened when, as an 8-year-old, I shattered a window with an errant throw of a rubber baseball. My expectations for punishment and sense of shame sent me into my bedroom closet, where I covered myself in clothes and cried. When she called my name, however, I came running. I couldn’t help myself. Hers was the voice of worry. Instead of chastisement, she showered me with the joy of reunion.

Whenever I entered her home or she came to stay with me, I felt almost overwhelmed by the force of her love. Nobody has taken more joy from my mere existence, nobody has hugged me harder or kissed my cheeks with greater suction. It’s easy enough to describe life as a “blessing,” but with her I felt that highest sense of worth. I never asked her pointedly, How could a woman who survived such horrors remain such a bottomless font of warmheartedness?

Our superhero came from another planet. Her accented English wasn’t an immigrant’s incomplete understanding of an adopted language. Somehow her language was richer, because she possessed an easy mastery of slang. When a granddaughter showed spunk, she would delight, “Oh boy, she is pistol.” Remarking on her height, she would say, “I’m a shrimp”—the comparison of herself to trayfe, which she never touched, was just funny. Even her malapropisms felt better than the idiom she intended. When we would go to Roy Rogers, she would insist that we order a side of the “french friers.” (To experience true joy was to go with her to the buffet in the strip mall and to know that you were encouraged to abandon all sense of human limitation in the face of such a miracle.)

Her instinct to live was an expression of the instinct to survive. Her presence was so full of life, and not just the way she whirled around her house, accomplishing tasks, making to-do lists and finishing them, filling used coffee tins with spare change that had been separated by the year of issuance, organizing immense piles of coupons for shopping trips that became gratis.

As a teenager, she was a communist, an act of rebellion in a small conservative shtetl. I imagine the intensity of her yearning for a better world, the romanticism that would lead her to dream like that. It was this rebellion, her sense that the Nazis might seek her out for special punishment, that prodded her to flee. Her story of survival was bound together with her capacity for free thinking and her ability to feel deeply.

Survival, in the end, feels like an insufficient word to explain her existence. To survive is to keep on breathing. But her talent was to relish a bag of Hershey Kisses, to place phone calls to distant cousins (albeit in a very loud voice and truncated to save on long distance), to suck the emotional marrow from a grandchild’s graduation, to clap her hands as she played with a baby, to loudly sing a prayer in synagogue two words ahead of the congregation. To be a survivor is to emphasize toughness. Her essence was sweetness. While her body withered and broke down, she distilled into this true self. She lay in bed, without ever remarking on her condition. She expressed gratitude for every sip of water and every stroke of her hair. Even as she died, she provided a master class in how to live.

It’s official: When Democrats take control of the House of Representatives next month, they will form a special new committee to examine climate change, Nancy Pelosi said in a statement on Friday.

Pelosi, likely the next speaker of the House, also announced that the new committee will be named the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. It will be led by Kathy Castor, a seven-term representative from Tampa Bay.

“The American people have demanded action to combat the climate crisis, which threatens our public health, our economy, our national security and the whole of God’s creation,” Pelosi said in the statement. “Congresswoman Castor is a proven champion for public health and green infrastructure, who deeply understands the scope and seriousness of this threat.”

Castor, a longtime member of the Energy and Commerce Committee, has already promised to decline all campaign contributions from coal, oil, or gas companies. Pelosi has not yet described exactly what the committee will do, but House committees of this type can hold hearings, write reports, and bring public attention to political issues.

With its formation, Pelosi makes good on her 2018 campaign promise to revive a special climate-focused committee. (After Republicans took control of the House in 2010, they shuttered the last special climate committee, which Pelosi established in 2007.) But the new committee arrives to a delicate family situation in the Democratic Party. A number of activists on the party’s left have greeted the announcement with frustration. They had hoped (and protested) for a more ambitious Green New Deal committee. Such a panel, they imagined, might finally draft a unified Democratic climate policy, a plan to improve the lot of American workers while massively overhauling the economy to prepare for climate change.

[Read: The Democratic Party wants to make climate policy exciting]

“It’s a big disappointment,” says Stephen O’Hanlon, a spokesman for the Sunrise Movement, a Millennial-led organization that championed the Green New Deal plan. “The select committee on a Green New Deal was put together based on a hard look at what the science demands, and we were hopeful that Nancy Pelosi—who says she wants to take serious action on climate change—would be willing to come to the table for it.”

“We’ll have to see what the actual mandate of the committee is,” he adds.

The Climate Crisis Committee seems likely to get a much narrower mandate than activists envisioned for a Green New Deal committee. It will probably not be allowed to issue subpoenas, as a permanent standing House committee can, nor will it be able to draft legislation. Overall, it will be less powerful than the last House select climate committee, which had subpoena power but not legislative authority.

Castor had been rumored to be Pelosi’s pick to lead the committee since last week. She gets high marks from the League of Conservation Voters, indicating a solid environmental record.

But in the past week, she has sometimes seemed ignorant of major disputes among climate activists. For instance, the Sunrise Movement initially sought to ban Green New Deal committee members from receiving donations of any kind from the fossil-fuel industry. When Castor heard that demand, she balked, claiming that the First Amendment made it impossible. Though she later walked back that comment, calling it “inartful”—and promised to forswear fossil-fuel donations herself—the episode suggested that she is unfamiliar with a constituency she will now have to entertain.

The demand should not have come as a shock: Fossil-fuel money has been a touchy subject for Democrats for years. As recently as August, climate activists warred with party moderates over whether it was appropriate to ban fossil-fuel donations for all Democrats, not just those on a climate-focused panel.

[Read: Democrats are shockingly unprepared to fight climate change]

It’s not yet clear whether Castor will impose such a ban on all members of the Climate Crisis Committee. Her office did not respond to a request for comment.

The most interesting aspect of today’s news may be the new committee’s name. Al Gore used the phrase climate crisis often, and even Hillary Clinton sometimes deployed it during the 2016 election. It feels tedious to unfurl its message—Democrats believe climate change is an emergency, obviously—but perhaps the name is a reminder of how much energy politics have changed in the last decade. In 2007, when Democrats last established a select committee on climate change, they chose a name much more fitting for an era of high oil prices: The House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming. Now, the United States is just a few years off from exporting more energy than it imports. Thanks to fracking and renewable energy, we’ve solved the problem of American “energy independence.” Global warming, meanwhile, continues to get worse.

This piece contains spoilers for the Black Mirror special “Bandersnatch.”

For most of its existence, Netflix’s streaming television service has largely existed to pump out more and more content. Its never-ending feed is packed with new shows, revived classics, licensed hits from other countries, and big acquisitions such as Black Mirror, a cult hit from the U.K.’s Channel 4 that tells warped Twilight Zone tales for an internet age. Given the onslaught of “more,” it stands to reason that eventually one television episode would offer the viewer thousands of choices all by itself. That is Black Mirror’s “Bandersnatch,” a feature-length special that behaves like a choose-your-own-adventure book, proposing various branching story options that lead the audience down different paths, many of them grim.

It’s a piece of interactive television that feels like an obvious new direction both for Netflix and for Black Mirror. It allows Netflix to harness its online platform in ways that classic broadcast television never could, letting subscribers choose plot options using their remote control and load every permutation of the story onto their site. And it allows Black Mirror’s creator and writer, Charlie Brooker, to explore the blinkered sense of freedom that comes from gaming—video gaming, especially. In “Bandersnatch,” the viewer is in control, nudging the main character, Stefan (Fionn Whitehead), to make various life choices, though the reality of the programming means there are only so many options.

[Read: The universe of ‘Black Mirror’ coalesces]

Brooker started his career as a game critic and writer, working for PC Zone magazine in the 1990s. Some of Black Mirror’s best episodes, such as “Fifteen Million Merits” and “Playtest,” explored the horrifying limits of futuristic gaming. “Bandersnatch” is set in 1984, at the height of computerized text adventures such as The Hobbit and Zork, which first introduced gamers to worlds that didn’t entirely proceed on rails. You could make choices, solve problems in different ways, and even arrive at different endings, much like you can in “Bandersnatch.”

The story itself is a simple bit of meta-narrative: Stefan is an aspiring programmer, who is building a game called Bandersnatch based on a fictional choose-your-own-adventure novel by a psychotic, now-dead cult author. He visits a cool gaming company and meets his idol, Colin Ritman (Will Poulter), and the business-minded manager Mohan Thakur (Asim Chaudhry). The latter offers Stefan a chance to create the game in-house, while the former stresses independence; it’s the first significant choice of many the viewer will make, picking between options that flash on the screen (if you don’t choose within 10 seconds, the show randomly chooses for you).

But there are insignificant picks the viewer can make, too, such as which breakfast cereal Stefan eats, or what music he listens to, or how he talks with his father, Peter (Craig Parkinson), and his therapist (Alice Lowe). Or are these choices so meaningless? With every click of a button, the story begins to snowball in weird and confusing directions, and the panicked sense of making the wrong pick every time increases the stakes. That’s the magic of video gaming, of course—the sense that you’re in control, that every right (or wrong) move is attributable to your thinking.

Games like BioShock have poked at the fallacy of that concept. Everything is, after all, programmed; even with advanced technology at work, there’s always going to be a limit to how much you can mimic real life through scripting and algorithms. In “Bandersnatch,” Brooker sometimes lets the viewer go back if a decision ends in Stefan’s death or artistic failure, much as you could always flip backward in a choose-your-own-adventure book, or reload from a save point in a video game. I explored various permutations of Stefan’s story before finally hitting a brick wall and an end-credits sequence (the entire viewing experience ran about 90 to 100 minutes for me, but it can be shorter or much longer).

The episode also, unsurprisingly for Black Mirror, veers into self-awareness; at one point, I communicated with Stefan through his computer screen, sending him messages about how I was watching him on Netflix (from the vantage of 1984, he was mostly baffled). At another moment, I loaded a completely pointless action scene that seemed to exist mostly to mock any complaint that things were getting too boring. I’m sure there are many more rabbit holes for me to tumble down, but the overall darkness of the story (Stefan is frequently being pushed toward madness) might make it a slog to watch over and over again.

Still, that’s the magic of video games: The more you play, the more you’re emotionally invested. Through the various branches I found, I never got to an ending of “Bandersnatch” that felt truly happy or fulfilling, though I’m sure one exists; the best (and last) one I arrived at was, at least, somewhat peaceful and touching, if a little mournful. But the show’s cleverest stroke of all came when I finally exited out of the episode and returned to Netflix’s main page. Next to “Bandersnatch” was a typical red progress bar, which usually indicates how many minutes you’ve watched a TV episode or movie. In the case of “Bandersnatch,” the bar was barely full; I’d just completed the story, but there are plenty of other completions to find. It’s fiendish stuff, but an undeniably clever new entry in the boundlessly reflective Black Mirror canon: the episode that never ends.

What better way to celebrate the remaining days of 2018 than by revisiting our favorite literary parties? There’s Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s take on Mrs. Dalloway and the dinner soirée, reimagined under the Donald Trump presidency. And, of course, who can forget Jay Gatsby’s infamous West Egg parties, which have inspired numerous high-school proms and costumed New Year’s shindigs.

That being said, not all fêtes are actually that fun: The author Alexander Chee explains how one scene in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette made him consider just how useful parties are for exploring a character’s anxieties and insecurities. Such is the case for Mary Bennet, of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, the oft-ignored and criticized Bennet sister. While readers may remember the Netherfield ball for Elizabeth Bennet’s tense (yet titillating) encounter with Mr. Darcy or Jane Bennet’s budding romance with Mr. Bingley, Mary’s story line that night is one of searing, public humiliation. And in Sean Ferrell’s Man in the Empty Suit, a lonely time-traveler hosts rather unconventional birthday parties: one where he visits his past and future selves, in the same spot, every year.

Each week in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas, and ask you for recommendations of what our list left out.

Check out past issues here, see what other Atlantic newsletter readers said were their favorite books of this year, and browse Atlantic writers’ and editors’ picks for the best books of 2018.

Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email. It’s been great reading with you this year. We’ll see you in 2019.

What We’re Reading

Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway gets a political remake

“[Chimamanda Ngozi] Adichie blends blunt, harvested-from-media-profiles observations about Trump—‘Donald disliked dissent’—with subtler, more intimate observations that come from Melania’s point of view.”

📚 “THE ARRANGEMENTS,” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 📚MRS. DALLOWAY, by Virginia Woolf

The sublime cluelessness of throwing lavish Great Gatsby parties

“Jay Gatsby’s weekend-long parties are lavish indictments of the whole, hard-charging scene that propelled him to sudden, extraordinary, unscrupulous wealth—‘a new world, material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about,’ as Fitzgerald writes toward the end.”

📚 THE GREAT GATSBY, by F. Scott Fitzgerald

How to write a party scene

“The qualities that make parties such a nightmare for people—and also so pleasurable—make them incredibly important inside of fiction. There’s a chaos agent quality to them: You just don’t know who’s going to be there, or why. You could run into an old enemy, an old friend, an old friend who’s become an enemy. You could run into an ex-lover, or your next lover. The stakes are all there, and that’s why they’re so fascinating.”

📚 VILLETTE, by Charlotte Brontë 📚 THE QUEEN OF THE NIGHT, by Alexander Chee

There’s something about Pride and Prejudice’s unappealing middle sister

“Mary is mocked by her sisters; she is insulted by her father (‘You have delighted us long enough,’ he informs her at the Netherfield ball, abruptly ending her pianoforte performance and promptly humiliating her); she is by most other people—and this is the thing that really oooooofs—merely tolerated.”

📚PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, by Jane Austen 📚 THE INDEPENDENCE OF MISS MARY BENNET, by Colleen McCullough 📚 THE FORGOTTEN SISTER: MARY BENNET’S PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, by Jennifer Paynter 📚 THE PURSUIT OF MARY BENNET, by Pamela Mingle 📚 A MATCH FOR MARY BENNET, by Eucharista Ward

Celebrating a birthday with your past and future selves

“The time traveler’s birthday party is a curious mix of memory, anticipation, and anxiety. The narrator sees himself in various stages of alcoholism, weight gain, and hair loss. He knows full well that he was or will be everyone he meets, and will experience the party through each of their eyes.”

📚MAN IN THE EMPTY SUIT, by Sean Ferrell

You RecommendLast week, we asked you to recommend stories about or related to food. Lisa Bolin Hawkins from Provo, Utah, suggested Julia Child’s My Life in France. “This autobiography … has food as a basic theme but is so much more about a fascinating woman’s struggle with her life and times,” Lisa wrote.“Ms. Child was trying to find her purpose in life, in her marriage, in Paris.” In Fried Walleye and Cherry Pie, edited by Peggy Wolff, 30 writers share gastronomic stories specific to the Midwest. “Their essays and memoirs reveal that within the context of food-based stories, the U.S. Midwest is fertile ground for meditations on the sense of place and on solid midwestern values: kindness, [familial love], an embrace of hard work and opportunity, politeness, and tradition,” Sam Gutterman, from Glencoe, Illinois, said.

What’s your favorite or most memorable literary party scene? Tweet at us with the hashtag #TheAtlanticBooksBriefing, or fill out the form here.

This week’s newsletter is written by J. Clara Chan. The book on her bedside table right now is Suicide Club, by Rachel Heng.

Comments, questions, typos? Email jchan@theatlantic.com.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

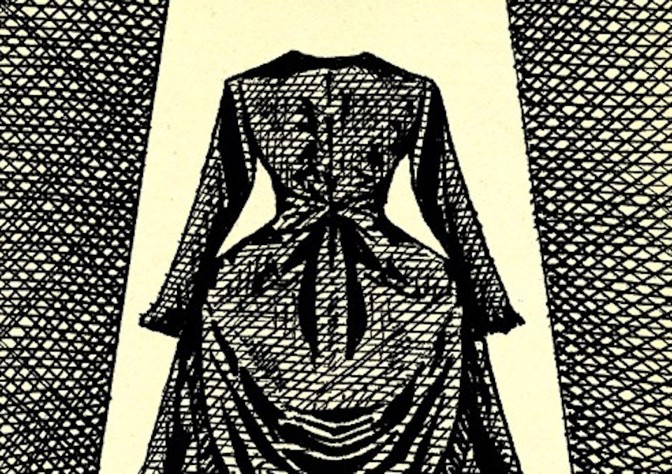

“Everyday life is very discomfiting,” the American writer and illustrator Edward Gorey told The National Observer in 1976. “I guess I’m trying to convey that discomfiting texture in my books.” But Gorey’s art did not merely aim to discompose audiences with its macabre Victorian-Edwardian overlays and casual depictions of darkly comic cruelty. It also sought to unsettle by resisting definitive explanations or solutions. In a later interview, Gorey clarified—in a manner of speaking—the dominant philosophical theme of his work: the power of the ineffable, the value of what is left unsaid. “Explaining something makes it go away ... Ideally, if anything were good, it would be indescribable,” grumbled Gorey, who died in 2000 at age 75. “Disdain explanation,” he similarly wrote in a meandering postcard to Andreas Brown, a fan and publisher of Gorey’s books.

The author is, of course, better known for his period Gothic aesthetic and funereal humor than for his skepticism of clarity. Gorey’s influence is evident throughout British and American pop culture, notably in works by Tim Burton—including the stop-motion films The Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride—and by Neil Gaiman, particularly the 2002 novella Coraline and its 2009 movie adaptation. Exhibitions of work by Gorey still routinely draw crowds today, much as his wildly popular and acclaimed 1977 stage adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula did decades ago.

At first glance, Gorey’s oeuvre might not appear to require much explication or invite readers to search meticulously for meaning. Most of Gorey’s books consist of brief blends of rhyme and lavish black-and-white drawings. Many seem to exist simply for the sake of existing. Such is the case with The Gashlycrumb Tinies—the first book of Gorey’s I read after stumbling across it in a London bookstore—a slim abecedarian that chronicles the ghastly demises of 26 children in a tone at once hilariously and eerily deadpan.

Because his books are slender and feature illustration, a medium long dismissed by establishment critics as less worthy of analysis than fine arts like painting, it is only relatively recently that Gorey has begun to receive scholarly attention. Many of his texts, under more scrutiny, are playfully and disturbingly irrational, resisting easy elucidation—a quality that reveals Gorey’s ideological views on both art and the universe. An impressively expansive new biography by Mark Dery, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, attempts, often with success, to demystify the illustrator’s wide-ranging elusiveness—a quality that was also explored in two recent art shows, Gorey’s Worlds and Murder He Wrote. To varying extents, the book and the exhibitions delve into both Gorey’s surrealism-influenced philosophy of art and into perhaps the ultimate puzzle of Gorey—the private life of the man himself.

The hallucinatory logic of surrealism, a 20th-century movement in the arts and philosophy that sought to capture the irrational air of dreams, pervades Gorey’s work. Surrealism “appeals to me,” Gorey said in 1978. “I mean that is my philosophy if I have one, certainly in the literary way … What appeals to me most is an idea by [the surrealist poet Paul] Éluard,” Gorey continued, referencing one of the movement’s founders. “He has a line about there being another world, but it’s in this one. And [the surrealist turned experimental novelist] Raymond Queneau said the world is not what it seems—but it isn’t anything else, either. Those two ideas are the bedrock of my approach.” Far from some purveyor of stock Gothic fare, Gorey embraced enigma and sought to relay, if indirectly, his surrealist philosophy through his art. “Gorey was a surrealist’s surrealist,” Dery aptly notes.

Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in The Doubtful Guest (1957): an illustrated poem in which a bizarre figure—part penguin, part reptile, wearing sneakers—shows up one night to a family’s house, uninvited, causing dismay and disarray. Gorey provides no sense of why it has come or when it might leave, a state of affairs resembling the existential absurdism of Franz Kafka or Albert Camus. The Doubtful Guest appeared the same year as Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat, another book in which an unexpected entrant brings anarchy into a home.

But whereas Seuss’s carnivalesque cat seeks to entertain, and cleans up before leaving so that the children don’t get in trouble when their mother returns, Gorey’s guest arrives with no clear agenda, does not remove its destructive messes, and shows no sign of departing. It is just comically, exasperatingly there, a discombobulation of domestic order far beyond the antics of Seuss’s feline. The Doubtful Guest distills Gorey’s surrealistic aesthetic into a stark message: that events resist human control, that the mysteries that lie in the mundane cannot be fully solved. It’s telling, too, that Murder He Wrote, an exhibition at the Edward Gorey House, explores how influential murder mysteries were for the writer—and yet his stories regularly subverted the genre’s promises of resolution, planting misleading clues and reveling in maddeningly ambiguous endings.

If Gorey’s work embraced the inexplicable, Gorey himself was as enigmatic and textured as his art. Bedecked, in his best-known look, in a Harvard scarf, half-moon spectacles, the thick beard of a wizard, a voluminous technicolor fur coat, and blue jeans with scuffed white Keds, Gorey was easily seen as a figure of delightful contradictions: ostentatious pomp on the one hand, a sort of suburban simplicity on the other. “Half bongo-drum beatnik, half fin-de-siècle dandy,” Stephen Schiff memorably described him in a New Yorker profile. As much a persona as a person, Gorey partly seemed like one of his own illustrations, a dapper Edwardian gentleman fresh from attending executions or exequies, while simultaneously bearing the aspect of some beach-combing uncle. Gorey enjoyed things ostensibly removed from the high elegance of his illustrations: watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Golden Girls with cats perched on his shoulder while he did crossword puzzles.

Gorey’s personal art collection, on display in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s 2018 exhibition Gorey’s Worlds, offers a rare window into some of the works that shaped his sensibility. Dozens of these pieces—by prominent European and American artists, as well as by lesser known folk artists—feature subjects that often surfaced in Gorey’s own creations: the ballet, cats, bats, shadowy landscapes. “These works give us as convincing a picture as we will probably ever have of Gorey’s elective affinities—of his own private tradition,” Jed Perl wrote for the New York Review of Books.

As Perl suggests, despite the overtness of Gorey’s outward eccentricities, the artist’s personal life was more shrouded. When pressed by interviewers about his sexuality, Gorey declined to give clear answers, except during a 1980 conversation with Lisa Solod, wherein he claimed to be asexual—making Gorey one of few openly asexual writers even today, a short list that includes the Kiwi novelist Keri Hulme. In his interview with Solod, Gorey said, “I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t identify with it much.” Yet this admission, Dery reveals, was deleted from the published version of their exchange, possibly by an editor who believed an openly gay author would be taken less seriously.

Gorey never expressly denied being homoromantic—attracted to men for the purpose of a relationship, not for sex—but, with the exception of that excised quote, he refused to pin down his desires, as most labels repulsed him. (One failing of Born to Be Posthumous is Dery’s repeated insistence on claiming Gorey was obviously gay by virtue of his “flamboyant dress” and “bitchy wit”; here, Dery falls into the trap of equating effeminacy with gay men, an archaic stereotype.) It seemed Gorey just wanted to be himself, whatever that might be, and often found the company of his pet felines as pleasurable, if not more, than that of his fellow humans. Indeed, when asked by Vanity Fair, “What or who is the greatest love of your life?” his reply was simply, “Cats.”

Perhaps fittingly, Gorey’s books also avoided depicting sex, even in the suggestively titled The Curious Sofa: A Pornographic Work by Ogdred Weary (an anagrammatic pseudonym for “Edward Gorey,” the first name of which also appeared as a vanity plate on Gorey’s yellow Volkswagen Beetle). The 1961 text consists of innuendo-laden sentences about the activities of a household of adults, a number of whom are described as “well-endowed,” but never, despite the subtitle, explicitly have intercourse. In the last scene, a man pulls the lever on a garish couch that seems to double as a machine. A woman screams, but Gorey never reveals what has happened; the reader must imaginatively fill in the blank.

In a relatively more straightforward—and, to me, more distressing—work, The Insect God (1963), the specter of sex also appears, but now as a possible punishment for a young girl who is kidnapped. At the start, the girl naively approached a vehicle filled with strangers, who offered her “a tin full of cinnamon balls” before they “lifted” her into the car; they brought her to be sacrificed before an insect deity, but “stunned” her and “stripped off her garments” first—an act laden with disquieting connotations of rape before murder.

Both of these stories contain subtle morals. The Insect God can be read as a demonstration of stranger danger. By never fully revealing the subtext of its lines, The Curious Sofa becomes a paean to intellectual curiosity, richer and curiouser if readers stop assuming the ending must involve pornography. But beyond that, the tales illustrate how the unexpected, and even horror, can enter at any time in Gorey’s world—and there is little, if anything, one can do to stop it.

Such is the case in Gorey’s heartbreaking tale The Hapless Child (1961), in which a young girl loses her parents and guardians one by one, until the family lawyer sends her to a school, where students torment her. She flees, then is abducted and sold into slavery to a dipsomaniacal “brute.” During one of her captor’s drunken stupors, the girl escapes but is run over by a car—that of her father, who, contrary to what she had been told, was not actually dead. To cap off the cruelty, the book ends with the revelation that the driver’s “dying child” is so emaciated that “he did not even recognize her.” Death, and suffering, is never far off in Gorey’s stories.

But nearer still is the profound sense of unfailing, even irrational cruelty in The Hapless Child’s narrative: the feeling that Gorey’s protagonist, who did not appear to do anything to deserve her fate, was just as helpless to do anything to soften it. After all, Gorey averred in a 1976 interview that “I stand by the idea that you can’t prevent things.” What does one do, when an ineffable universe sets its sights on you?

In 1984, Gorey declared that “my mission in life is to make everybody as uneasy as possible ... because that’s what the world is like.” Gorey’s longtime friend, the writer Alexander Theroux, recorded the artist remarking that “life is intrinsically ... boring and dangerous at the same time. At any given moment, the floor may open up. Of course, it almost never does.” Gorey’s books unquestionably achieve unease—even wordless tales like The West Wing, which unnerve solely by their sepulchral atmospherics. But Gorey’s tales are also ludic, winking at the reader with a combination of frightfulness and fun that is apparent throughout the pieces featured in Murder He Wrote and Gorey’s Worlds. Ultimately, Gorey’s work is an altar to the writer’s faith in art as a medium for attempting to translate the untranslatable language of living.

Amid the terror and tumult of the world today, the floor may already feel as if it has opened up, again and again. Gorey chose to reweave horror into odd but indelible imagery. At least, his work suggests, art can console in times of dismay, and, perhaps more important, unsettle when one grows too consoled.

Recently, Joe Pinsker talked to a handful of experts about why many ultrarich people are motivated to accumulate more and more wealth. There are two central questions people ask themselves when determining whether they’re satisfied, one researcher explained: Am I doing better than I was before? and Am I doing better than other people?

My grown sons and I have often discussed the puzzle of the wealthy who want more money and the powerful who want more power. It’s nice to know that this question has actually drawn some academic study. As a member of the middle class who’d appreciate a little more economic security, I still feel a little sorry for these folks. To never be satisfied, to be driven to nonstop competition is a sorry existence, even if said existence is spent upon a golden throne. Too bad this population doesn’t add some creativity to its desires and strive to make the world a better place.

Janet Audette

Arvada, Colo.

This article was just as depressing to read as I imagine the research was to conduct. In a time of so much overabundance, it strikes me that so many people still live without the basic needs for survival.

California, where I live and work, is the world’s fifth-largest economy, thanks in part to many of the kind of high-net-worth individuals who were studied here. Even though the state’s GDP is doing so well, millions of people who live here don’t feel any of the benefits.

Almost 20 percent of California’s population lives below the federal poverty line—2 million are kids. I know humans are notoriously bad at learning from history, but I still wonder at the fact that we’ve never fully grasped the notion that the more extreme the disparity between the haves and the have-nots, the higher the likelihood of a society becoming unstable for everyone (see: the French Revolution).

The super-wealthy in California and beyond remain largely untouched by the unsustainable tendencies of our economic system. But as drought and fire and displacement become more common, even the superrich will eventually come face-to-face with their place in humanity—as part of it.

As we move into a new decade of uncertainty around the quality of our shared infrastructure and the stability of world political and economic systems, it seems that the only way forward is for individuals and private interests to wake up to their responsibility to the collective. Deploying their accumulated wealth for the public good would not be solely altruistic—it would also be an investment in the ability to continue playing the game of acquiring wealth.

Courtney McKinney

Sacramento, Calif.

Certainly the rich can be greedy, self-centered, and overly focused on image, appearance, and their peer group. They can also be unhappy with their level of success. But I’d argue that you can find those elements at all economic levels. I’d be more interested in levels of happiness within groups (i.e., are successful hedge-fund traders more or less unhappy than those who build conventional businesses), and evaluating which groups at various socioeconomic levels are most happy and what characteristics contribute to that. That would be a much harder article to write, with difficult research. But the answers might actually benefit readers by giving them concrete directions to pursue happiness versus an article that’s really about why a non-rich person can have moral superiority over a really rich one—which, quite frankly, is what this article is about, in my view.

Joe Schmitz

Orange County, Calif.

I recall reading what I think was a Wall Street Journal article in the late ’80s summarizing research that examined incomes and happiness in a novel way. The researchers started with entry-level incomes and asked respondents, “How much more money would you need to be happy?” On average, as I remember it, they said 15 percent more. They then went to folks earning 15 percent more than the entry level and asked, “How much more money would you need to be happy?” You guessed it, the answer was about 15 percent more.

No matter the income level surveyed, the results were always the same. Folks think they need about 15 percent more than they currently make to be happy.

Thirty years later I still think I need about 15 percent more to be happy!

Vogel Da

Sellersville, Pa.

There used to be a simple solution to this: The 90 percent–plus marginal income-tax rates applied to the highest bracket during the 1950s. If 90 percent or more of the multimillion-dollar salary the CEO was demanding was going to go the government in taxes, he may have been less likely to ask for it. And if he demanded it anyway, for the sake of “status,” society became its prime beneficiary. Why do we so studiously ignore this effective countermeasure to the ever-growing income gap?

Carlos D. Luria

Salem, S.C.

Over the next week, The Atlantic’s “And, Scene” series will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy cinematic moment from 2018. Next up is Christopher McQuarrie’s Mission: Impossible—Fallout. (Read our previous entries here.)

The ludicrously dubbed “Impossible Mission Force,” the imaginary federal agency at the heart of the Mission: Impossible franchise, is difficult to define. Its members are international superspies with a gift for stagecraft; imagine MI6, but with an elaborate makeup department, a healthy CGI budget, and a flair for dramaturgy. Ethan Hunt (played by Tom Cruise) and his pals might combat villains by jumping off a building or executing a daring car chase, but they’re also fond of masks and voice-changers, and they always seem to have a wardrobe of disguises in tow. “The IMF is like Halloween, a bunch of grown men in rubber masks playing trick or treat,” sighs the CIA chief Erica Sloane (Angela Bassett).

But the beginning of Fallout, the sixth entry in the Mission: Impossible film franchise, suggests that the world has gotten too grim for fun and games. When the series launched in 1996, it was a hearty throwback, reviving a hit 1967 TV show for the decade’s biggest star. By 2018, Hunt is a man haunted by his years in the field, a marriage he had to abandon for work, and villains that are hell-bent not on financial gain or political power, but on apocalyptic destruction. Fallout is the third Mission: Impossible in a row in which the bad guy has decided that Earth is beyond saving and needs to be annihilated. And at its beginning, that’s exactly what seems to have happened.

[Read: ‘Mission: Impossible—Fallout’ doubles down on the ridiculousness of its hero]

In the film’s first scene, a sting operation to seize plutonium that’s floating around on the black market goes wrong, with Hunt saving his teammates and letting the fissile material get away. Fade to: a CNN broadcast, hosted by Wolf Blitzer, saying that three nuclear attacks have devastated Rome, Jerusalem, and Mecca. “We can assume the death toll is catastrophic,” Blitzer intones in the background of a hospital room, as Hunt enters to interrogate the captured scientist Nils Debruuk (Kristoffer Joner), who is suspected of building the bombs for the terrorist John Lark. It’s classic good cop/bad cop: Hunt threatens to kill Debruuk, is restrained by his fellow agent Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), and then reluctantly assents to Debruuk’s request that Lark’s nihilistic manifesto be read on-air by Blitzer. Satisfied with the political triumph, Debruuk confesses.

It speaks to just how grim big Hollywood franchises have gotten that I fell for it. After all, this was the year that saw the Avengers movie end with half the heroes getting zapped into dust and antiheroes such as Venom and Deadpool rule the box-office roost. Maybe the Mission: Impossible creative team decided it had to raise the stakes and kick things off with something truly unthinkable, rather than relying on the usual high-tech, gadget-fueled fun. Debruuk’s confession is followed by one of the most satisfying, and ridiculous, rug-pulls of the series. His hospital room is revealed to be a facsimile, constructed by the IMF. Wolf Blitzer is the agent Benji Dunn (Simon Pegg), wearing a rubber mask. “Told you we’d get it,” Blitzer crows, satisfied.

The hilarious twist—which helps the IMF track the location of the missing plutonium—serves as a mission statement for the movie, and the series at large, one that the film doubles down on for the rest of its running time. The IMF might be playing Halloween, reliant on absurd theatricality rather than brute strength, but that’s why people buy tickets: They’re here to see Hunt and company cleverly wriggle their way out of every situation, not do battle in a world that’s already aflame. Beginning a 2018 blockbuster with a literal “fake news” sequence might have felt like a cheap bit of topicality from another franchise, but Fallout’s version serves as a reminder that international spy thrillers don’t have to be all death and destruction to make an impact. The real world might seem on the brink of chaos, but at least in the theater, Ethan Hunt is always on hand to drag it back to safety through sheer force of will.

Previously: Leave No Trace

Next Up: A Star Is Born

One-third of Americans aren’t able to name all of their grandparents, according to the genealogy website Ancestry.com. That proportion seems very, very high—it represents more than 100 million people. Can that estimate really be right?

Ancestry filled in some details when I inquired. The figure comes from a survey the company recently commissioned that polled 2,000 American adults who were “statistically representative” of the country’s overall population. In the survey, respondents were asked whether they knew the first names of their grandparents, and were not given any indication that they were being asked exclusively about their biological grandparents.

When I asked Ancestry for possible explanations of its finding, the company noted that many family trees are passed down orally, which might make familial details prone to being misremembered or forgotten. It also pointed out that a lot of kids grow up calling their grandparents nicknames or just “Grandma” or “Grandpa”—which could make it more likely that they’d blank when asked to provide their grandparents’ actual first names.

In an attempt to better understand what else might be going on, I consulted some researchers who study family-related demographic patterns. Because these experts didn’t have access to the details of the survey’s methodology, their theories aren’t definitive explanations of Ancestry’s finding. But they are informed guesses, and together they capture the multifarious forms that American families take in the 21st century.

[Read: How do you grandparent a 20-year-old?]

“I wouldn’t have any way of assessing the 1/3 number, but it doesn’t surprise me,” says Philip Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland. Cohen and the two other researchers I emailed with brought up a variety of family structures that might complicate people’s awareness of their family line—single parenting, assisted reproductive technology, divorces, nonmarital child-rearing, adoption, and blended families.

Robert Crosnoe, a sociology professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said that many kids cycle through a variety of these family structures as they grow up, which means the regular introduction of new relatives. “There is more to keep track of, more to lose track of, and some family relationships may get lost in all of that churning,” Crosnoe told me. “You could see how a grandparent or two could lose visibility.” (He noted that while one-third seems high, he expects the actual proportion to be “not negligible.”)

Molly Fox, an anthropologist at UCLA, brought up several other demographic trends that could help explain the survey finding. First, she mentioned “immigration patterns to the U.S. over the past 50 years, as the geographic and linguistic separation of grandparents and grandchildren could fracture intergenerational family connections.” Another: “Diminishing family sizes in the U.S., such as having few siblings or few aunts and uncles compared to previous generations, could mean there are fewer sources for a person to call upon when trying to reconstruct the names of relatives in previous generations.”

Fox also wondered “how the ability to name your grandparents relates to them being alive during your lifetime, and perhaps events like WWII or the Vietnam War that resulted in a surge of early-adult deaths in the U.S. could have diminished the life span overlap of grandparents and grandchildren.”