Dentre os vários derrotados nas eleições brasileiras de 2018, um em especial já havia perdido a disputa bem antes do primeiro turno. A rara unanimidade de candidatos e programas à direita e à esquerda, conservadores e até autointitulados liberais garantiu a vitória contra o licenciamento ambiental.

Prevalece entre os setores políticos, em especial no legislativo, e em parte da sociedade, a percepção de que o licenciamento é culpado por não termos estradas suficientes, ferrovias, linhas de transmissão, portos, usinas, indústrias, importantes projetos minerários. Se a greve dos caminhoneiros parou o país, disseram os oportunistas, boa parte da culpa é das licenças para modais alternativos que nunca saem. A ferrovia ferrogrão, a BR-319, o linhão de Tucuruí e os novos blocos do pré-sal estariam aí para comprovar como o licenciamento é um entrave ao desenvolvimento do país.

As propostas de solução para o “problema” são um show de horrores: temos que escolher entre uma ampla flexibilização da legislação ou o estabelecimento de prazo máximo para a emissão de licenças. Se o órgão X não se manifestar no tempo Y, é como se não houvesse discordância e o licenciamento é feito por W.O.

Mais do que a avaliação de viabilidade, importa aqui o cronograma da obra, os prazos do empreendedor. Uma completa inversão de prioridades. Subentendida, ainda, a noção absurda de que as licenças devem ser obrigatoriamente emitidas.

Na quarta-feira, dia 12, o próprio presidente eleito Jair Bolsonaro disparou sobre como “fica difícil empreender num país como esse aqui”. A frase foi uma referência às dificuldades do governo do Paraná em construir uma rodovia em um dos últimos blocos bem preservados de Mata Atlântica do Brasil. A obra tem como objetivo principal facilitar o acesso a um porto privado no litoral paranaense e enfrenta forte resistência por causa dos impactos e das falhas nos estudos ambientais.

A barragem de Mariana não se rompeu por excesso de “burocracia”. Foi justamente o contrário.Como solução ao “problema do licenciamento”, a equipe de transição do novo governo já propõe revogar vários decretos que tratam do tema, assim como passar a atribuição do licenciamento do Ministério do Meio Ambiente para a Presidência da República, criando uma Secretaria de Licenciamento Estratégico.

Desmantelar o Ministério do Meio Ambiente, flexibilizar e afrouxar regulamentações para destravar licenças parecem ser o caminho que o governo escolheu. Para desatar esse nó discursivo sem passar pelo desmonte de uma das mais importantes barreiras a projetos ineficientes, caros e de grande impacto socioambiental, precisamos olhar o cenário com um pouco mais de cuidado. E talvez perceber que o “problema” a ser enfrentado é mais um problema cognitivo de quem fez o diagnóstico do que outro vício burocrático incorrigível deste país de vícios burocráticos incorrigíveis. Afinal, a barragem de fundão em Mariana, Minas Gerais, não se rompeu por excesso de “burocracia”. Foi justamente o contrário.

Sabe-se que a estrutura dos órgãos licenciadores é precária, que o orçamento desta área tão estratégica não para de sofrer cortes, que os servidores estão se aposentando às centenas sem reposição e que muitas regras que norteiam a condução dos estudos deveriam ser mais claras, que falta integração entre os agentes e órgãos governamentais envolvidos.

Também ajudaria muito ter alguma sinalização prévia em zoneamentos específicos pelo governo de quais são as regiões preferenciais para investimento e quais as regiões onde uma licença ambiental levaria a impactos tão grandes que o processo seria complexo, caro e com grandes chances de negativa. Afinal, estamos no Brasil, o país mais biodiverso do mundo, onde um simples inventário de biodiversidade, o ponto de partida para uma avaliação de impactos adequada, pode ter logística e complexidade técnica sem precedentes. Mas nada disso parece ser levado em conta nas grandes discussões sobre as melhorias do licenciamento.

Uma questão talvez ainda mais importante como fator indutor de atrasos e dificuldades no processo também é frequentemente ignorada, apesar de já ter sido identificada em todos os diagnósticos mais sérios feitos pelos próprios órgãos ambientais, pelo Ministério Público e pelo Tribunal de Contas da União: a responsabilidade das empresas ao apresentar péssimos estudos ambientais.

Lembro bem da primeira vez em que trabalhei com um estudo ambiental muito ruim, que me pareceu à época uma exceção extravagante, mas que eu viria a descobrir que é situação assustadoramente recorrente. Tratava-se da implementação de uma pequena usina hidrelétrica no interior de Rondônia, para a qual deveríamos refazer todos os estudos ambientais. O original, sumariamente recusado no órgão local, era um emaranhado de textos colados quase aleatoriamente, mapas sem resolução e listas de espécies com erros primários, inclusive contendo espécies de outros biomas. Tudo isso tornava impossível a tarefa de entender o básico: como era a área onde se pretendia instalar o empreendimento, o que havia ali, como a operação da usina impactaria a região, de que forma poderia ser mitigado ou compensado – em resumo, o bê-a-bá do licenciamento ambiental. Não havia nenhum item completo de modo correto.

Com maiores ou menores carências, a maioria esmagadora dos estudos ambientais precisa retornar aos empreendedores para complemento, em uma ordem de grandeza que pode chegar a nove de cada 10 processos. Um vai-e-vem que emperra a decisão sobre as licenças, atrasa os ritos, sobrecarrega os órgãos ambientais e abre caminho para judicialização, que atravanca tudo mais um pouco. Cada estudo tem milhares de páginas, modelagens complexas em temas diversos e imensos buracos de informação. Quando finalmente são analisados, entram e saem da fila para pedidos de complemento.

O Ibama tem hoje 2.800 estudos para analisar e apenas 300 servidores. Apesar disso, chegou a 1.300 pareceres em 2017 e caminha bem com o cronograma dos projetos prioritários do governo. Mas ainda é insuficiente para encerrar a fila interminável. Destaco aqui um trecho elucidador de uma carta aberta das entidades que representam os servidores a respeito de acusações de que o licenciamento é demasiado lento:

“Destaque-se, portanto, que o licenciamento seria mais rápido caso os empreendedores de fato dessem a importância necessária para os estudos e programas ambientais, assegurando qualidade ao menos satisfatória dos trabalhos a serem entregues ao Ibama – a crítica à qualidade desses trabalhos não é feita apenas pelo corpo técnico do Ibama, mas por diversos atores envolvidos no licenciamento, como o Ministério Público da União e a sociedade civil organizada.”

Em agosto de 2017, o órgão precisou dar um ultimato à petroleira francesa Total, que pretende explorar petróleo na foz do Amazonas: “Caso o empreendedor não atenda aos pontos demandados pela equipe técnica mais uma vez, o processo de licenciamento será arquivado”. Era a terceira vez que os estudos, que foram definitivamente rejeitados na última semana, eram submetidos com os mesmos problemas.

No começo de novembro, foi a vez da petroleira britânica BP ter estudos devolvidos para complementação. Detalhe: eram projetos semelhantes ao da Total, na mesma região e com as mesmas lacunas de informação. Como os processos são públicos e contêm informações estratégicas para a obtenção das licenças, é de se estranhar que o diagnóstico da primeira não haja sido aproveitado pela segunda empresa em seu diagnóstico.

No licenciamento ambiental da Ferrogrão, uma ferrovia de 1.000 km que conectará a soja produzida na região Centro-Oeste aos portos para escoamento na bacia do Amazonas, outra obra consagrada por seus problemas com o licenciamento, o Ministério Público interveio e pediu a suspensão do processo:

“O diagnóstico apresentado tem falhas consideradas graves pela Justiça, como omissão das comunidades quilombolas afetadas e cópia de trechos de estudos feitos para as hidrelétricas da bacia do Tapajós. O relatório (…) utilizou imagens do Google Earth como ferramenta de diagnóstico, deixou de realizar estudos técnicos prévios essenciais, não trouxe entrevistas com moradores, não levantou vestígios culturais e arqueológicos no traçado da ferrovia.”

Mas, afinal de contas, por que muitas empresas parecem incapazes de apresentar estudos que contemplem as solicitações ou parecem deliberadamente insubordinadas aos ritos definidos pela Constituição no Brasil?

Em muitos casos, o empreendedor é o próprio governo, que também financia e licencia os projetos, expondo um óbvio conflito de interesse.Essa resposta tem dois aspectos importantes. O primeiro é econômico, na medida em que estudos completos são mais caros e demorados, encontram mais “problemas” e encarecem também o financiamento dos programas de mitigação de impactos ao longo da obra. Essas ações incluem, por exemplo, resgate de fauna em área desmatada, construção de sistemas de esgoto e planos de reassentamento para as pessoas afetadas. Parece mais fácil deixar que o órgão ambiental indique as lacunas que consegue encontrar, preenchê-las de qualquer jeito e obter a licença. A ironia é que o rigor técnico das avaliações muitas vezes faz o esforço original do estudo se perder, com solicitação de mais estudos de campo, mais análises, mais tempo, tornando as licenças mais custosas em tempo e dinheiro.

O segundo aspecto é de governança, que torna o ato de emissão de licenças permeável a decisões políticas. Um estudo ruim pode ser aprovado, e as exigências podem ser empurradas com a barriga se você tem a seu favor a imprensa, o governo, a opinião pública ou qualquer tipo de constrangimento. Em muitos casos, o empreendedor é o próprio governo, que também financia e licencia os projetos, expondo um óbvio conflito de interesse.

Como o empreendedor é quem tem a obrigação de apresentar os estudos ambientais, sua ação poderá estar influenciada por um ou ambos os aspectos, variando na intensidade. Assim, muitas empresas de consultoria ambiental vêm se aprimorando como especialistas na aprovação de licenças em vez de prestar serviços de assessoria técnica. Esta situação fragiliza muito o processo e gera riscos às pessoas e aos ambientes diretamente afetados.

A operação Lava Jato iluminou esta questão recentemente com a exposição de um cartel de empresas que se revezavam para assumir os projetos mais “complicados” por conta da expertise em construir a aprovação de grandes obras (e também por sua disposição em participar de esquemas de desvio de dinheiro público). Entre as diversas práticas descritas, estavam a ocultação de espécies ameaçadas das áreas afetadas, a subestimação de impactos e a adulteração de relatórios de consultores. Uma destas empresas era a Leme Engenharia, responsável pelo Estudo de Impacto Ambiental de Belo Monte, uma obra apresentada em 2009 que trazia 15 mil páginas de informações, mas que assustava mais pelas páginas que deixava de trazer.

Belo Monte veio cercada de tanta polêmica que imediatamente a sociedade civil se organizou para uma análise “independente” dos estudos, sendo o Painel de Especialistas o documento mais relevante produzido, embora não o único. Eram mais de 200 páginas demonstrando a insuficiência dos estudos, a ocultação de impactos e vários problemas metodológicos.

Apesar disso, e mesmo contra a opinião dos próprios servidores, o Ibama concedeu em 2010 a licença prévia, a primeira de três que compõem o rito do licenciamento de grandes obras. Ela elencou 40 requisitos que deveriam ser trabalhados antes da segunda licença.

Mas com o sinal dado e a disposição demonstrada pelo governo em fazer a obra a qualquer custo, as condições não seriam cumpridas. Dilma Rousseff já garantia, desde quando era ministra de Minas e Energia, entre berros e entrevistas, que Belo Monte iria sair “no horizonte mais rápido possível”.

Uma reunião fechada na primeira semana do seu governo selou o destino da segunda licença da usina e o então presidente do Ibama pediu exoneração por não concordar com a pressão pela liberação da licença de instalação. Na sequência, um sujeito chamado Américo Ribeiro Tunes assumiu interinamente o órgão, emitiu uma licença parcial e deixou o cargo no mês seguinte. Na falta de requisitos para emitir a licença prevista em lei, emitiu uma licença que não existe e entrou para a gloriosa história da burocracia brasileira. E, assim, fez a obra andar, consolidando a ideia de que Belo Monte estava imune à legislação do licenciamento.

Aliás, imune no sentido literal: ao fim de 2012 já eram mais de 50 questionamentos na justiça, que não tinham efeito sobre a construção por conta de um instrumento da ditadura, a suspensão de segurança, que permite suspender unilateralmente decisões de instâncias inferiores por um suposto risco de “ocorrência de grave lesão à ordem, à saúde, à segurança e à economia públicas”.

Nove anos depois, a ausência de licenciamento ambiental foi o principal fator que levou Altamira ao caos completo, à destruição de aldeias indígenas, a uma interminável lista de exigências não cumpridas (a despeito de já ter licença para operar), a uma conta de R$ 39 bilhões – grande parte dinheiro público. Sem mencionar a imensa desconfiança sobre sua utilidade para o país nos termos em que a obra foi imposta. Todos estes indícios, somados às evidências produzidas na operação Lava Jato, reforçam a hipótese de que Belo Monte talvez não tivesse propósito primeiro de produzir energia, como se denunciou desde o início.

Belo Monte é mais um dos vários maus exemplos do que acontece quando se faz um licenciamento de fachadaÉ claro que é descabido generalizar o modelo Belo Monte – de ocultar, depois contestar e, por fim, ignorar os impactos dos empreendimentos, confiando na interferência política e na imunidade ao judiciário – para todos os estudos ruins que atravancam o dia a dia dos órgãos ambientais. Mas tampouco se pode imaginar que se trata de um caso isolado. Não é. Uma olhada mais próxima no licenciamento das usinas de Jirau e Santo Antônio, na década passada, ou no interminável processo de asfaltamento da BR-319, no trecho que liga Porto Velho a Manaus, revela os sinais do que se configura um modus operandi já bem estabelecido em grandes projetos, em especial quando o governo é quem empreende.

Belo Monte é mais um dos vários maus exemplos do que acontece quando se faz um licenciamento de fachada, apenas para formalizar burocracias. O procedimento é e deve ser complexo e abrangente – como são os desafios de se empreender em um país com tão estupenda diversidade biológica e cultural. Respeitar esses ritos é proteger nosso patrimônio socioambiental e favorecer alternativas mais amigáveis à sua conservação. Esse patrimônio é, em última instância, o nosso futuro.

O grave contexto de crise fiscal no governo com a estagnação econômica do país levou ao sucateamento dos órgãos licenciadores e acirrou os ânimos bem no momento em que é necessário encaminhar discussões complexas, essencialmente técnicas. O licenciamento se encontra fragilizado e sob risco iminente de que se tomem medidas prejudiciais ao país em longo prazo.

Vai ser desastroso para o país se o licenciamento deixar de ser a principal trincheira de defesa ambiental para se tornar, de fato, uma mera burocracia, a papelada inútil que o futuro presidente já o acusa de ser. Uma espécie de profecia autorrealizável cada vez mais próxima de se concretizar.

The post Não são os ativistas ou o Ibama que emperram grandes obras. São estudos ambientais mal feitos. appeared first on The Intercept.

Há duas histórias para a trajetória de sucesso da grife feminina Amissima. A versão glamour é a da marca de roupas presente em dois templos paulistanos do luxo (os shoppings Cidade Jardim e JK Iguatemi), liderada pela diretora de estilo da marca, a sul-coreana Suzana Cha. Não é só isso. A Amissima também emplaca vestidos em capas de revistas, viaja com jornalistas a Paris – as fotos estão nas redes sociais da marca – e conta com influenciadoras como @luizabsobral, @lelesaddi e @thassianaves para exibir os modelos da grife para milhares de seguidores no Instagram.

A outra história, desumana e sem sofisticação, é a da empresa que lucrou à base de trabalho análogo ao de escravo.

O Intercept teve acesso exclusivo a uma investigação de auditores fiscais do trabalho em São Paulo que descobriu que, em pelo menos duas das 25 oficinas de costura que produzem exclusivamente para a marca, os trabalhadores são submetidos à condições análogas à de escravo. Ainda segundo os agentes, as demais 23 oficinas apresentam indícios de condições semelhantes, o que será verificado em desdobramentos da operação.

No dia 6 de novembro, visitei duas delas junto com os auditores da Superintendência Regional do Trabalho e Emprego de São Paulo, que investigam as irregularidades.

As oficinas terceirizadas que produzem com exclusividade para a marca funcionam em imóveis degradados em bairros periféricos de São Paulo. São contratadas diretamente pela Amissima, sem intermediários. O ambiente é abafado e inseguro. De frente para a rua, em uma sala retangular espaçosa, sete máquinas de costura trabalhavam sob uma lona e um teto de isopor. Nem a nossa presença interrompeu a produção.

A oficina também funciona como casa para muitas famílias que costuram para a marca e dividem o mesmo imóvel. A prática é ilegal. Ali, os trabalhadores aceitam um esquema de divisão de pagamento chamado “um terço”: um terço do valor da peça fica com o trabalhador, outro terço vai para as despesas da casa, divididas igualmente entre todos, e o último terço para o dono da oficina (a pessoa que assume a negociação com a empresa).

Assim, dos R$ 9 que a Amissima paga para a oficina por peça, R$ 3 vão para o costureiro. O resto vai para a casa e para o dono da oficina – em geral, outro migrante nas mesmas condições.

Entre lenços e sem documentosNas oficinas, a rotina é sufocante. Os funcionários costumam trabalhar das 8h às 22h, com rápidos intervalos para as refeições – todas feitas no mesmo ambiente. Os pagamentos são feitos de acordo com a produtividade e a qualidade nas entregas.

Nas duas oficinas, 14 costureiros bolivianos foram encontrados entre amontoadas de tecidos e máquinas de costura. Nenhum tinha carteira de trabalho assinada, e dois não tinham sequer documentos brasileiros. Alguns desempenhavam a função há anos – o caso mais antigo é de 2012. Os auditores fotografaram tudo, recolheram documentos e peças piloto: quatro vestidos, um top cropped e uma blusa de cetim.

O Ministério Público do Trabalho autuou a Amissima por 23 irregularidades depois da operação. A marca terá de pagar R$ 553 mil em indenização aos trabalhadores. Com o fundo de garantia, os trabalhadores receberão perto de 600 mil.

Tecidos, linhas e remédios para dor“Você não arrematou a roupa? Você viu a foto, ela falou que vai descontar seu prêmio, tá bom?”, diz uma das funcionárias da Amissima em mensagem de WhatsApp enviada para um dos costureiros e interceptada pelo Ministério Público do Trabalho.

Na marca, “prêmio” não é bônus ou gratificação. Os trabalhadores esclareceram que o “prêmio” é o valor do pagamento integral pela costura da peça e serve para pressionar os oficinistas a entregarem no prazo correto e sem defeitos. Ficar sem “prêmio” significa, portanto, ter descontado cerca de 15% por peça, mesmo depois de refazer o serviço e entregar o produto como o cliente pediu. “Para mim, não tem prêmio. Só desconto”, disse um dos trabalhadores resgatados.

Quem avança nas horas trabalhadas e, assim, costura mais peças, ganha mais. “[Os costureiros] estavam submetidos a uma jornada não menor do que 13 horas de trabalho diárias, mas habitualmente de 14 horas”, diz o relatório dos auditores sobre as jornadas exaustivas, um dos elementos que caracterizam o crime, segundo o Código Penal. Para costurar para a marca, eles eram submetidos a 70 horas de trabalho por semana – no mínimo.

Esse sistema de produção os pressiona a trabalhar até a exaustão, de segunda a sábado – incluindo feriados –, o ano todo, “sem condições de repor as forças, de curtir os filhos, de ter lazer, um vazio completo de humanidade”, afirmou o auditor fiscal do trabalho Luis Alexandre de Faria.

Por isso, analgésicos, antiinflamatórios e cintas ortopédicas para aliviar a dor lombar dividem espaço na oficina com linhas e tecidos e cadeiras sem encosto, regulagem e, em muitos casos, quebradas.

Segundo os depoimentos e registros encontrados, cada trabalhador recebia cerca de R$ 900 por mês – o piso da categoria para oito horas de trabalho diárias é de R$ 1.450,02. O salário, além de baixo, era pago sem regularidade – em geral, depois do pagamento da Amissima pelo lote. Os funcionários também não recebiam FGTS, férias com adicional, 13º salários ou adicional por horas extras.

Vida sem escolhasNa blitz promovida na oficina que presta serviços para a Amissima, um dos casais resgatados vivia em um cubículo onde cabe uma cama, uma máquina de costura e um armário pequeno, sem privacidade ou ventilação, separado da cozinha de uso coletivo por uma cortina de chuveiro. Lâmpadas pendiam do teto, aumentando riscos de incêndio, segundo os fiscais.

Em uma das oficinas, um sobrado com uma espécie de subsolo, os fiscais encontraram cinco extintores de incêndio vencidos – alguns há 15 anos. Em um longo corredor empoeirado e mal iluminado, ficavam o banheiro, a casa-oficina de um casal que paga aluguel, a cozinha e um estoque de botijões de gás. Ao lado, uma sala onde cinco crianças, todas menores de dez anos, brincavam enquanto os adultos costuravam.Dois rapazes solteiros dividiam espaço com as famílias. Na parte de cima, outros quartos improvisados e um banheiro de uso comum. “Você tem um risco adicional pelas crianças, expostas a desconhecidos”, disse a auditora Lívia dos Santos Ferreira.

“Moramos apertados. Se a gente recebesse direito, poderíamos ter uma oficina, uma casa grande. Se pagassem pelo menos 10% do valor (vendido ao público) de peça, viveríamos em uma condição melhor”, disse um dos costureiros. Em média, a Amissima paga pouco mais de 1% do valor da peça na loja ou no e-commerce da marca. Ele, como os demais, pediu anonimato por segurança e por medo de perder o contrato. Como outros na mesma situação, migrou da Bolívia para fugir da pobreza. No Brasil, já trabalhou com outras marcas, que pagavam pior ainda, segundo ele.

Isso é trabalho escravoTanto a gestão de Michel Temer quanto a de Bolsonaro caminham para afrouxar as regras de combate ao trabalho degradante. O primeiro tentou tornar mais difícil enquadrar um trabalhador como escravo. Também empregou um ministro que tinha um histórico de violações trabalhistas. Mas Bolsonaro vai mais longe: o presidente eleito já anunciou a extinção do Ministério do Trabalho, que é o órgão responsável por coordenar o tipo de fiscalização que flagrou os escravizados da Amissima.

Na semana passada, a Comissão Nacional para a Erradicação do Trabalho Escravo relatou “profunda preocupação com a política de descontinuidade da política de enfrentamento ao trabalho escravo, especialmente quanto às ações de fiscalização coordenadas pelo Ministério do Trabalho.”

Durante a campanha, Bolsonaro foi um dos candidatos que não se comprometeram com o combate a regimes de trabalho análogos à escravidão. Na verdade, o presidente eleito já demonstrou que não sabe o que é trabalho escravo, assim como seu antecessor, Michel Temer, que comparou situações degradantes à mera ausência de “uma saboneteira” no banheiro da empresa.

Tecnicamente, para que uma situação seja enquadrada como análoga à escravidão, é preciso que existam graves violações a direitos fundamentais. Jornada exaustiva, condições degradantes e submeter os funcionários a riscos de saúde ou de vida, por exemplo. Além disso, essa prática também dá uma vantagem ilegal à empresa frente à concorrência, explica Giuliana Cassiano, auditora fiscal do trabalho. “O consumidor é quem tem mais poder para coibir esses crimes, porque é ele quem diz sim ou não para um produto que é produzido com trabalho escravo.”

Por telefone, o CEO da Amissima, Jaco Yoo, afirmou que errou ao não fiscalizar as condições de trabalho nas oficinas contratadas pela marca e lamentou pelos migrantes sem documentação. “Meus pais vieram da mesma situação (eram migrantes). Sei das dificuldades, jamais faria isso.”

Disse, ainda, que pagava semanalmente as oficinas, o que os trabalhadores negam, e que eles não “produziam muito”. Também prometeu contratar metade dos costureiros para trabalhar na empresa.

The post Exclusivo: com vestidos a R$ 800, grife Amissima faz roupas com trabalho escravo appeared first on The Intercept.

Sen. James Inhofe, an Oklahoma Republican recently elevated to chair the Senate Armed Services Committee after the death of John McCain, was implicated recently in what looked to be an insider trading scandal. A few days after meeting with President Donald Trump and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis to successfully advocate for a military budget increase, Inhofe purchased between $50,000 and $100,000 of stock in defense contractor Raytheon, which stands to profit from additional defense spending.

Inhofe tried to manage the controversy by claiming that a third-party financial adviser handles his stocks and made the purchase without his knowledge. Minutes after being questioned about the trades, he wrote a letter to his adviser, asking him to no longer trade defense or aerospace stocks. Inhofe has even taken to carrying around a card with a stock reply to journalists about the matter.

But the Raytheon trades represent only a fraction of his trading activity. The same day that Inhofe revealed the Raytheon purchase, he also disclosed the sale of between $15,000 and $50,000 worth of stock from Celgene, a biotech firm, along with a similarly sized sale of stock in Aptiv, the auto parts maker formerly known as Delphi. A month earlier, Inhofe revealed trades in General Electric, Salesforce.com, American International Group, XPO Logistics, Albemarle, Intuitive Surgical, and Intellia Therapeutics.

There’s no way to test Inhofe’s claim that a third party manages his stock portfolio, absent a monitor tracking Inhofe 24/7: He could make a phone call or send a message to direct a trade at anytime. But it’s clear that Inhofe is trading millions of dollars worth of stock a year, while voting on legislation that affects public companies.

It’s clear that Inhofe is trading millions of dollars worth of stock a year, while voting on legislation that affects public companies.In fact, over the course of 2018, Inhofe has made 57 individual stock trades, according to Senate disclosure forms. The value of these trades totaled somewhere between $1.72 million and $4.11 million. In 2017, according to Inhofe’s annual report, he made another 52 trades.

Congress attempted to prevent legislators from insider trading with the 2012 STOCK Act, which prohibits members and their staffs from exploiting insider information discovered in the course of policy deliberations. But unlike corporate “insiders,” members of Congress are not required to establish arms-length trading plans — nor has the House fully cooperated with efforts by the Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate potential wrongdoing.

When compared to corporate insiders, members of Congress are exposed to a much broader array of insider information which implicates a wide range of companies. Given that members of Congress hold a unique position of public trust, Sens. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., and Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, both potential Democratic presidential candidates, want to put a stop to all the trading. Last week, they introduced legislation that would permanently ban members of Congress and senior staff from trading individual stocks.

“We should not be in the position of thinking about legislation in the context of personal investment,” Merkley told The Intercept in an interview. “As long as you own stocks, it’s hard to rule out of your mind. And the public sees it as a conflict of interest.”

“We should not be in the position of thinking about legislation in the context of personal investment.”Under the Ban Conflicted Trading Act, all members would have six months after enactment to divest their shares. New members would get six months from their entry into Congress to divest. Members and senior staff could also opt to transfer stocks to an independent blind trust, or hold them for as long as they served in government, as long as they do not sell or buy more stocks. Diversified mutual funds or exchange-traded funds would still be allowed.

Merkley questioned whether the Inhofe situation represented a true blind trust. Without assurance that a lawmaker has no role in stock-picking, public cynicism over their trading will remain. “You would have to be legitimately, 100 percent blind,” he said.

Another section of the bill prohibits members from serving as officers on corporate boards, which amazingly is not already disallowed. Rep. Chris Collins, R-N.Y., was indicted earlier this year for advising friends and family to dump shares of the biopharmaceutical company Innate Immunotherapeutic after learning that a clinical trial for the company’s key multiple sclerosis drug failed. Collins knew about the failure before it was public, because he sat on the company’s board.

Currently, Senate ethics rules ban members and staff from serving as board members of publicly traded companies, but House rules do not. Even the Senate rules permit board membership of tax-exempt organizations. Merkley believes codifying into law a full prohibition on members of the House or Senate serving on corporate boards would be beneficial.

The Collins indictment, incidentally, was the one and only instance of a prosecution under the 2012 STOCK Act. While a 2017 Public Citizen report did show that the STOCK Act has reduced market trading activity among members of Congress, it still found between $104 million and $337 million in trades by U.S. senators in 2015, which was the last year studied.

Individual incidents continue to dog the reputation of Congress. In 2017, former Congressperson Tom Price’s confirmation hearing for secretary of health and human services was dominated by questions about his numerous stock holdings in health-related companies. Price made several pharmaceutical stock trades on the same day that he pressured regulators to repeal a rule that would harm drug company profits.

In addition, there are numerous instances of senators trading stocks of companies they nominally oversee through committee work, as the Public Citizen report indicates: Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., has recently traded hundreds of thousands worth of stock in energy infrastructure businesses while sitting on the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee. Sen. Thad Cochran, R-Miss., is also a busy player in energy stocks while sitting on the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development. Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and Pat Toomey, R-Pa., actively trade in health care stocks while serving on health care subcommittees. Sen. Tom Udall, D-N.M., trades in natural resources and precious metals stock while on subcommittees that oversee these industries.

(Cochran is no longer in the Senate, having resigned due to health concerns in April.)

“We really have to establish a public trust of behavior.”“We really have to establish a public trust of behavior,” Merkley said. “As public officials, there are a lot of impositions on our lives. This is not one of them. Having a diversified portfolio is an easy thing.”

Banning congressional stock trading could also make it easier to pass a 0.1 percent tax on stock trades, which the Congressional Budget Office this week estimated would raise $777 billion over 10 years.

Under the bill, if members or senior staff are found to have traded stocks while in office, the congressional Ethics Committees would be empowered to fine them no less than 10 percent of the value of the investment. Of course, congressional Ethics Committees are made up of members of Congress, and they have historically been rather lax in enforcing rules against fellow members. It will also be a challenge for the Merkley bill to pass the Republican-controlled Senate in the first place.

Separate from Merkley’s proposed legislation, Federal Trade Commissioner Rohit Chopra has called for an independent Public Integrity Protection Agency, which would consolidate enforcement capability that is currently spread around the government and would have the ability to investigate and penalize government officials and those seeking influence. Asked about the idea, Merkley responded, “My first impression is that an office dedicated to the mission of transparency and accountability sounds great.”

Democrats in the House have prepared a broad anti-corruption bill for their first act when they take over Congress next year, but while it beefs up some restrictions on members and provides new enforcement powers to the Office of Government Ethics, it does not include anything on congressional stock trading.

Merkley’s choice to spearhead anti-corruption efforts might be read as part of his efforts to distinguish himself in a crowded 2020 primary field. When asked about his presidential ambitions, Merkley told The Intercept, “I’m exploring it and will decide within the first quarter [of next year].”

The post Sen. Jeff Merkley Wants to Stop Congress Members From Insider Trading By Banning Them From Owning Stocks appeared first on The Intercept.

Google has been forced to shut down a data analysis system it was using to develop a censored search engine for China after members of the company’s privacy team raised internal complaints that it had been kept secret from them, The Intercept has learned.

The internal rift over the system has had massive ramifications, effectively ending work on the censored search engine, known as Dragonfly, according to two sources familiar with the plans. The incident represents a major blow to top Google executives, including CEO Sundar Pichai, who have over the last two years made the China project one of their main priorities.

The dispute began in mid-August, when the The Intercept revealed that Google employees working on Dragonfly had been using a Beijing-based website to help develop blacklists for the censored search engine, which was designed to block out broad categories of information related to democracy, human rights, and peaceful protest, in accordance with strict rules on censorship in China that are enforced by the country’s authoritarian Communist Party government.

The Beijing-based website, 265.com, is a Chinese-language web directory service that claims to be “China’s most used homepage.” Google purchased the site in 2008 from Cai Wensheng, a billionaire Chinese entrepreneur. 265.com provides its Chinese visitors with news updates, information about financial markets, horoscopes, and advertisements for cheap flights and hotels. It also has a function that allows people to search for websites, images, and videos. However, search queries entered on 265.com are redirected to Baidu, the most popular search engine in China and Google’s main competitor in the country. As The Intercept reported in August, it appears that Google has used 265.com as a honeypot for market research, storing information about Chinese users’ searches before sending them along to Baidu.

According to two Google sources, engineers working on Dragonfly obtained large datasets showing queries that Chinese people were entering into the 265.com search engine. At least one of the engineers obtained a key needed to access an “application programming interface,” or API, associated with 265.com, and used it to harvest search data from the site. Members of Google’s privacy team, however, were kept in the dark about the use of 265.com.

Several groups of engineers have now been moved off of Dragonfly completely and told to shift their attention away from China.

The engineers used the data they pulled from 265.com to learn about the kinds of things that people located in mainland China routinely search for in Mandarin. This helped them to build a prototype of Dragonfly. The engineers used the sample queries from 265.com, for instance, to review lists of websites Chinese people would see if they typed the same word or phrase into Google. They then used a tool they called “BeaconTower” to check whether any websites in the Google search results would be blocked by China’s internet censorship system, known as the Great Firewall. Through this process, the engineers compiled a list of thousands of banned websites, which they integrated into the Dragonfly search platform so that it would purge links to websites prohibited in China, such as those of the online encyclopedia Wikipedia and British news broadcaster BBC.

Under normal company protocol, analysis of people’s search queries is subject to tight constraints and should be reviewed by the company’s privacy staff, whose job is to safeguard user rights. But the privacy team only found out about the 265.com data access after The Intercept revealed it, and were “really pissed,” according to one Google source. Members of the privacy team confronted the executives responsible for managing Dragonfly. Following a series of discussions, two sources said, Google engineers were told that they were no longer permitted to continue using the 265.com data to help develop Dragonfly, which has since had severe consequences for the project.

“The 265 data was integral to Dragonfly,” said one source. “Access to the data has been suspended now, which has stopped progress.”

In recent weeks, teams working on Dragonfly have been told to use different datasets for their work. They are no longer gathering search queries from mainland China and are instead now studying “global Chinese” queries that are entered into Google from people living in countries such as the United States and Malaysia; those queries are qualitatively different from searches originating from within China itself, making it virtually impossible for the Dragonfly team to hone the accuracy of results. Significantly, several groups of engineers have now been moved off of Dragonfly completely, and told to shift their attention away from China to instead work on projects related to India, Indonesia, Russia, the Middle East and Brazil.

Records show that 265.com is still hosted on Google servers, but its physical address is listed under the name of the “Beijing Guxiang Information and Technology Co.,” which has an office space on the third floor of a tower building in northwest Beijing’s Haidian district. 265.com is operated as a Google subsidiary, but unlike most Google-owned websites — such as YouTube and Google.com — it is not blocked in China and can be freely accessed by people in the country using any standard internet browser.

The internal dispute at Google over the 265.com data access is not the first time important information related to Dragonfly has been withheld from the company’s privacy team. The Intercept reported in November that privacy and security employees working on the project had been shut out of key meetings and felt that senior executives had sidelined them. Yonatan Zunger, formerly a 14-year veteran of Google and one of the leading engineers at the company, worked on Dragonfly for several months last year and said the project was shrouded in extreme secrecy and handled in a “highly unusual” way from the outset. Scott Beaumont, Google’s leader in China and a key architect of the Dragonfly project, “did not feel that the security, privacy, and legal teams should be able to question his product decisions,” according to Zunger, “and maintained an openly adversarial relationship with them — quite outside the Google norm.”

Last week, Pichai, Google’s CEO, appeared before Congress, where he faced questions on Dragonfly. Pichai stated that “right now” there were no plans to launch the search engine, though refused to rule it out in the future. Google had originally aimed to launch Dragonfly between January and April 2019. Leaks about the plan and the extraordinary backlash that ensued both internally and externally appear to have forced company executives to shelve it at least in the short term, two sources familiar with the project said.

Google did not respond to requests for comment.

The post Google’s Secret China Project “Effectively Ended” After Internal Confrontation appeared first on The Intercept.

Former Vice President Joe Biden believes that “anybody can beat” President Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

While speaking at a recent event promoting his new book, “American Promise,” Biden said, “I think I’m the most qualified person in the country to be president.”

After delivering an address at the Lantos Foundation’s 10th anniversary gala, where he was recognized with a legacy award, Biden was asked specifically by The Intercept why he thinks he’s the most qualified person to take on Trump.

“You don’t run for president unless you think you are qualified,” Biden replied.

“Why do you think you could beat President Trump? Why is this your time?” the former Delaware senator was asked.

“I think anybody can beat him,” Biden responded.

Biden has said that he expects to make a decision on entering the 2020 race within the next two months. Polls have been consistently showing Biden as a frontrunner should he jump in, but that strong showing may be due to universal name identification and lingering good feelings from some Democratic voters toward the Obama administration. Biden ran twice for president previously, in 1988 and 2008, faring terribly both times.

The Lantos Foundation honored Biden as Inaugural Recipient of the Decennial Lantos Legacy Award. According to its official website, the foundation “was established to continue Tom Lantos’ proud legacy as an ardent champion for human rights by carrying, in his words, ‘the noble banner of human rights to every corner of the world.’”

The post Joe Biden on Donald Trump: “I Think Anybody Can Beat Him” appeared first on The Intercept.

A children’s speech pathologist who has worked for the last nine years with developmentally disabled, autistic, and speech-impaired elementary school students in Austin, Texas, has been told that she can no longer work with the public school district, after she refused to sign an oath vowing that she “does not” and “will not” engage in a boycott of Israel or “otherwise tak[e] any action that is intended to inflict economic harm” on that foreign nation. A lawsuit on her behalf was filed early Monday morning in a federal court in the Western District of Texas, alleging a violation of her First Amendment right of free speech.

The child language specialist, Bahia Amawi, is a U.S. citizen who received a master’s degree in speech pathology in 1999 and, since then, has specialized in evaluations for young children with language difficulties (see video below). Amawi was born in Austria and has lived in the U.S. for the last 30 years, fluently speaks three languages (English, German, and Arabic), and has four U.S.-born American children of her own.

Amawi began working in 2009 on a contract basis with the Pflugerville Independent School District, which includes Austin, to provide assessments and support for school children from the county’s growing Arabic-speaking immigrant community. The children with whom she has worked span the ages of 3 to 11. Ever since her work for the school district began in 2009, her contract was renewed each year with no controversy or problem.

But this year, all of that changed. On August 13, the school district once again offered to extend her contract for another year by sending her essentially the same contract and set of certifications she has received and signed at the end of each year since 2009.

She was prepared to sign her contract renewal until she noticed one new, and extremely significant, addition: a certification she was required to sign pledging that she “does not currently boycott Israel,” that she “will not boycott Israel during the term of the contract,” and that she shall refrain from any action “that is intended to penalize, inflict economic harm on, or limit commercial relations with Israel, or with a person or entity doing business in Israeli or in an Israel-controlled territory.”

The language of the affirmation Amawi was told she must sign reads like Orwellian — or McCarthyite — self-parody, the classic political loyalty oath that every American should instinctively shudder upon reading:

That language would bar Amawi not only from refraining from buying goods from companies located within Israel, but also from any Israeli companies operating in the occupied West Bank (“an Israeli-controlled territory”). The oath given to Amawi would also likely prohibit her even from advocating such a boycott given that such speech could be seen as “intended to penalize, inflict economic harm on, or limit commercial relations with Israel.”

Whatever one’s own views are, boycotting Israel to stop its occupation is a global political movement modeled on the 1980s boycott aimed at South Africa that helped end that country’s system of racial apartheid. It has become so mainstream that two newly elected members of the U.S. Congress explicitly support it, while boycotting Israeli companies in the occupied territories has long been advocated in mainstream venues by Jewish Zionist groups such as Peace Now and the Jewish-American Zionist writer Peter Beinart.

This required certification about Israel was the only one in the contract sent to Amawi that pertained to political opinions and activism. There were no similar clauses relating to children (such as a vow not to advocate for pedophiles or child abusers), nor were there any required political oaths that pertained to the country of which she is a citizen and where she lives and works: the United States.

In order to obtain contracts in Texas, then, a citizen is free to denounce and work against the United States, to advocate for causes that directly harm American children, and even to support a boycott of particular U.S. states, such as was done in 2017 to North Carolina in protest of its anti-LGBT law. In order to continue to work, Amawi would be perfectly free to engage in any political activism against her own country, participate in an economic boycott of any state or city within the U.S., or work against the policies of any other government in the world — except Israel.

That’s one extraordinary aspect of this story: The sole political affirmation Texans like Amawi are required to sign in order to work with the school district’s children is one designed to protect not the United States or the children of Texas, but the economic interests of Israel. As Amawi put it to The Intercept: “It’s baffling that they can throw this down our throats and decide to protect another country’s economy versus protecting our constitutional rights.”

Amawi concluded that she could not truthfully or in good faith sign the oath because, in conjunction with her family, she has made the household decision to refrain from purchasing goods from Israeli companies in support of the global boycott to end Israel’s decadeslong occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

Amawi, as the mother of four young children and a professional speech pathologist, is not a leader of any political movements: She has simply made the consumer choice to support the boycott by avoiding the purchase of products from Israeli companies in Israel or the occupied West Bank. She also occasionally participates in peaceful activism in defense of Palestinian self-determination that includes advocacy of the global boycott to end the Israeli occupation.

Watch The Intercept’s three-minute video of Amawi, as she tells her story, here:

Video by Kelly West

When asked if she considered signing the pledge to preserve her ability to work, Amawi told The Intercept: “Absolutely not. I couldn’t in good conscience do that. If I did, I would not only be betraying Palestinians suffering under an occupation that I believe is unjust and thus, become complicit in their repression, but I’d also be betraying my fellow Americans by enabling violations of our constitutional rights to free speech and to protest peacefully.”

As a result, Amawi informed her school district supervisor that she could not sign the oath. As her complaint against the school district explains, she “ask[ed] why her personal political stances [about Israel and Palestine] impacted her work as a speech language pathologist.”

In response, Amawi’s supervisor promised that she would investigate whether there were any ways around this barrier. But the supervisor ultimately told Amawi that there were no alternatives: Either she would have to sign the oath, or the district would be legally barred from paying her under any type of contract.

Because Amawi, to her knowledge, is the only certified Arabic-speaking child’s speech pathologist in the district, it is quite possible that the refusal to renew her contract will leave dozens of young children with speech pathologies without any competent expert to evaluate their conditions and treatment needs.

“I got my master’s in this field and devoted myself to this work because I always wanted to do service for children,” Amawi said. “It’s vital that early-age assessments of possible speech impairments or psychological conditions be administered by those who understand the child’s first language.”

In other words, Texas’s Israel loyalty oath requirement victimizes not just Amawi, an American who is barred from working in the professional field to which she has devoted her adult life, but also the young children in need of her expertise and experience that she has spent years developing.

The anti-BDS Israel oath was included in Amawi’s contract papers due to an Israel-specific state law enacted on May 2, 2017, by the Texas State Legislature and signed into law two days later by GOP Gov. Greg Abbott. The bill unanimously passed the lower House by a vote of 131-0, and then the Senate by a vote of 25-4.

When Abbott signed the bill in a ceremony held at the Austin Jewish Community Center, he proclaimed: “Any anti-Israel policy is an anti-Texas policy.”

The bill’s language is so sweeping that some victims of Hurricane Harvey, which devastated Southwest Texas in late 2017, were told that they could only receive state disaster relief if they first signed a pledge never to boycott Israel. That demand was deeply confusing to those hurricane victims in desperate need of help but who could not understand what their views of Israel and Palestine had to do with their ability to receive assistance from their state government.

The evangelical author of the Israel bill, Republican Texas state Rep. Phil King, said at the time that its application to hurricane relief was a “misunderstanding,” but nonetheless emphasized that the bill’s purpose was indeed to ensure that no public funds ever go to anyone who supports a boycott of Israel.

At the time that Texas enacted the law barring contractors from supporting a boycott of Israel, it was the 17th state in the country to do so. As of now, 26 states have enacted such laws — including blue states run by Democrats such as New York, California, and New Jersey — while similar bills are pending in another 13 states.

This map compiled by Palestine Legal shows how pervasive various forms of Israel loyalty oath requirements have become in the U.S.; the states in red are ones where such laws are already enacted, while the states in the darker shade are ones where such bills are pending:

Map: Palestine Legal

The vast majority of American citizens are therefore now officially barred from supporting a boycott of Israel without incurring some form of sanction or limitation imposed by their state. And the relatively few Americans who are still free to form views on this hotly contested political debate without being officially punished are in danger of losing that freedom, as more and more states are poised to enact similar censorship schemes.

One of the first states to impose such repressive restrictions on free expression was New York. In 2016, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order directing all agencies under his control to terminate any and all business with companies or organizations that support a boycott of Israel. “If you boycott Israel, New York State will boycott you,” Cuomo proudly tweeted, referring to a Washington Post op-ed he wrote that touted that threat in its headline.

As The Intercept reported at the time, Cuomo’s order “requires that one of his commissioners compile ‘a list of institutions and companies’ that — ‘either directly or through a parent or subsidiary’ — support a boycott. That government list is then posted publicly, and the burden falls on [the accused boycotters] to prove to the state that they do not, in fact, support such a boycott.”

Like the Texas law, Cuomo’s Israel order reads like a parody of the McCarthy era:

What made Cuomo’s censorship directive particularly stunning was that, just two months prior to issuing this decree, he ordered New York state agencies to boycott North Carolina in protest of that state’s anti-LGBT law. Two years earlier, Cuomo banned New York state employees from all nonessential travel to Indiana to boycott that state’s enactment of an anti-LGBT law.

So Cuomo mandated that his own state employees boycott two other states within his own country, a boycott that by design would harm U.S. businesses, while prohibiting New York’s private citizens from supporting a similar boycott of a foreign nation upon pain of being barred from receiving contracts from the state of New York. That such a priority scheme is so pervasive — whereby boycotts aimed at U.S. businesses are permitted or even encouraged, but boycotts aimed at Israeli businesses are outlawed — speaks volumes about the state of U.S. politics and free expression, none of it good.

Following Cuomo, Texas’s GOP-dominated state legislature, and numerous other state governments controlled by both parties, the U.S. Congress, prodded by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, began planning its own national bills to use the force of law to punish Americans for the crime of supporting a boycott of Israel. In July of last year, a group of 43 senators — 29 Republicans and 14 Democrats — supported a law, called the Israel Anti-Boycott Act (S. 720), introduced by Democratic Sen. Benjamin Cardin of Maryland, that would criminalize participation in any international boycott of Israel.

After the American Civil Liberties Union issued a statement vehemently condemning Cardin’s bill as an attack on core free speech rights, one which “would punish individuals for no reason other than their political beliefs,” numerous senators announced that they were re-considering their support.

But now, as The Intercept reported last week, a modified version of the bill is back and pending in the lame-duck session: “Cardin is making a behind-the-scenes push to slip an anti-boycott law into a last-minute spending bill being finalized during the lame-duck session.”

The ACLU has also condemned this latest bill because “its intent and the intent of the underlying state laws it purports to uphold are contrary to the spirit and letter of the First Amendment guarantee of freedoms of speech and association.” As the ACLU warned in a recent action advisory:

While that “new version clarifies that people cannot face jail time for participating in a boycott,” the ACLU insists that “it still leaves the door open for criminal financial penalties” for anyone found to be participating in or even advocating for a boycott of Israel.More dangerous attacks on free expression are difficult to imagine. Nobody who claims to be a defender of free speech or free expression — on the right, the left, or anything in between — can possibly justify silence in the face of such a coordinated and pure assault on these most basic rights of free speech and association.

One common misconception is that the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech only bars the state from imprisoning or otherwise punishing people for speaking, but does not bar the state from conditioning the receipt of discretionary benefits (such as state benefits or jobs) on refraining from expressing particular opinions. Aside from the fact that, with some rare and narrow exceptions, courts have repeatedly held that the government is constitutionally barred under the First Amendment from conditioning government benefits on speech requirements — such as, say, enacting a bill that states that only liberals, or only conservatives, shall be eligible for unemployment benefits — the unconstitutional nature of Texas’s actions toward Bahia Amawi should be self-evident.

Imagine if, instead of being forced by the state to vow never to boycott Israel as a condition for continuing to work as a speech pathologist, Amawi was instead forced to pledge that she would never advocate for LGBT equality or engage in activism in support of or opposition to gun rights or abortion restrictions (by joining the National Rifle Association or Planned Parenthood), or never subscribe to Vox or the Daily Caller, or never participate in a boycott of Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, Cuba, or Russia due to vehement disagreement with those governments’ policies.

The tyrannical free speech denial would be self-evident and, in many of those comparable cases, the trans-ideological uproar would be instantaneous. As Lara Friedman, president of the Foundation for Middle East Peace, warned: “[T]his template could be re-purposed to bar contracts with individuals or groups affiliated with or supportive of any political cause or organization — from the political Left or Right — that the majority in a legislature or the occupant of a governor’s office deemed undesirable.”

Recall that in 2012, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel tried to block zoning permits allowing Chick-fil-A to expand, due to his personal disagreement with the anti-LGBT activism of that company’s top executive. As I wrote at the time in condemning the unconstitutional nature of the mayor’s actions: “If you support what Emanuel is doing here, then you should be equally supportive of a Mayor in Texas or a Governor in Idaho who blocks businesses from opening if they are run by those who support same-sex marriage — or who oppose American wars, or who support reproductive rights, or who favor single-payer health care, or which donates to LGBT groups and Planned Parenthood, on the ground that such views are offensive to Christian or conservative residents.”

Those official efforts in Chicago (followed by mayors of other liberal cities) to punish Chick-fil-A due to its executive’s negative views on LGBT equality were widely condemned even by liberal commentators, who were horrified that mayors would abuse their power to condition zoning rights based on a private citizen’s political viewpoints on a controversial issue. Obviously, if a company discriminated against LGBT employees in violation of the law, it would be legitimate to act against them, but as Mother Jones’s Kevin Drum correctly noted, this was a case of pure censorship: “There’s really no excuse for Emanuel’s and [Boston Mayor Thomas] Menino’s actions. … You don’t hand out business licenses based on whether you agree with the political views of the executives. Not in America, anyway.”

The ACLU of Illinois also denounced the effort by Chicago against Chick-fil-A as “wrong and dangerous,” adding: “We oppose using the power and authority of government to retaliate against those who express messages that are controversial or averse to the views of current office holders.” That, by definition, is the only position that a genuine free speech defender can hold — regardless of agreement or disagreement with the specific political viewpoint being punished.

Last week, the ACLU’s Senior Legislative Counsel Kate Ruane explained why even the modified, watered-down, fully bipartisan version of the Israel oath bill pending in the U.S. Congress, and especially the already enacted bills in 26 states of the kind that just resulted in Amawi’s termination, are a direct violation of the most fundamental free speech rights:

This is a full-scale attack on Americans’ First Amendment freedoms. Political boycotts, including boycotts of foreign countries, have played a pivotal role in this nation’s history — from the boycotts of British goods during the American Revolution to the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the campaign to divest from apartheid South Africa. And in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, the Supreme Court made clear that the First Amendment protects the right to participate in political boycotts.

The lawsuit which Amawi filed similarly explains that “economic boycotts for the purposes of bringing about political change are entrenched in American history, beginning with colonial boycotts on British tea. Later, the Civil Rights Movement relied heavily on boycotts to combat racism and spur societal change. The Supreme Court has recognized [in Claiborne] that non-violent boycotts intended to advance civil rights constitute ‘form[s] of speech or conduct that [are] ordinarily entitled to protection under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.'”

Who can justify that — as a condition for working with speech-impaired and developmentally disabled children — Amawi is forced by the state to violate her conscience and renounce her political beliefs by buying products from a country that she believes (in accordance with the U.N.) is illegally and brutally occupying land that does not belong to it? Whether or not you agree with her political view about Israel and Palestine, every American with an even minimal belief in the value of free speech should be vocally denouncing the attack on Amawi’s free speech rights and other Americans who are being similarly oppressed by these Israel-protecting censorship laws in the U.S.

As these Israel oath laws have proliferated, some commentators from across the ideological spectrum have noted what a profound threat to free speech they pose. The Foundation for Middle East Peace’s Friedman, for instance, explained that “it requires little imagination to see how criminalizing Americans’ participation in political boycotts of Israel could pave the way for further infringements to Americans’ right to support or join internationally-backed protests on other issues.” She correctly described such laws as “a free speech exception for Israel.”

The libertarian lawyer Walter Olson, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute’s Center for Constitutional Studies, similarly warned: “It is not a proper function of law to force Americans into carrying on foreign commerce they personally find politically objectionable, whether their reasons for reluctance be good, bad, or arbitrary.”

National Review’s Noah Daponte-Smith last year denounced the Cardin bill seeking to criminalize advocacy of the Israel boycott as “so mind-bogglingly stupid that it’s hard to know exactly what to say about it,” adding that the bill “penalizes political beliefs and so is both unconstitutional and unconscionable.” The conservative writer continued: “The senators who currently support it should be, quite frankly, ashamed of themselves; they have lost sight of one of the founding principles of American government, allowing it to be overshadowed by the spectral world of the Israeli–Palestinian dispute.”

Meanwhile, though, there is an entire pundit class that has made very lucrative careers from posing as defenders and crusaders for free speech — from Jonathan Chait, Bill Maher, and Bari Weiss to the glittering renegades of the intellectual dark web — who fall notoriously silent whenever censorship is aimed at critics of Israel (there are some rare exceptions, such as when Chait tweeted about Cardin’s bill: “BDS is awful, but this bill criminalizing it sounds insane and unconstitutional,” and when Weiss criticized Israel for barring a Jewish-American boycott advocate from entering).

CNN’s recent firing of Marc Lamont Hill due to his pro-Palestine speech, and the threats from the chair of Temple University’s Board of Trustees to fire Hill from his tenured position over his contempt for the views expressed in that speech, produced not a word of protest from this crowd. The same was true of the University of Illinois’s costly decision to rescind a teaching offer to Palestinian-American professor Steven Salaita for the thought crime of condemning Israel’s bombing of Gaza.

But as The Intercept has repeatedly documented, the most frequent victims of official campus censorship are not conservative polemicists but pro-Palestinian activists, and the greatest and most severe threat posed to free speech throughout the west is aimed at Israel critics — from the arresting of French citizens for the “crime” of wearing “Boycott Israel” T-shirts to Canadian boycott activists being overtly threatened with prosecution to the partial British criminalization of the boycott of Israel.

Put simply, it is impossible to be a credible, effective, genuine advocate of free speech and free discourse without objecting to the organized, orchestrated, sustained onslaught of attacks on the free speech and free association rights undertaken specifically to protect the Israeli government from criticism and activism. Self-professed free speech defenders who only invoke that principle when their political allies are targeted are, by definition, charlatans and frauds. Genuine free speech advocates object to censorship even when, arguably especially when, the free speech rights of their political adversaries are assaulted.

Anyone who stands by silently while Bahia Amawi is forced out of the profession she has worked so hard to construct all because of her refusal to renounce her political views and activism — while the young children she helps are denied the professional support they need and deserve — can legitimately and accurately call themselves many things. “Free speech supporter” is most definitely not one of them.

The post A Texas Elementary School Speech Pathologist Refused to Sign a Pro-Israel Oath, Now Mandatory in Many States — so She Lost Her Job appeared first on The Intercept.

Threat Report: The Senate Intelligence Committee released two new commissioned reports that illustrate just how heavily Russian disinformation efforts targeted African-American voters in the 2016 presidential election—using strategies similar to the Trump campaign’s, writes David A. Graham. An unrelated report released Monday by foreign-policy experts says that though the current administration is lucky that it hasn’t yet faced a large-scale international crisis, a cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure and networks by a state actor ranks as one of its highest risks for 2019.

Legal Lurch: A federal judge in Texas ruled last Friday that the Affordable Care Act is unconstitutional. The case faces another trip through the courts, and even if higher courts don’t sustain the Texas ruling, uncertainty around the future of the health law will still cause turmoil for many people. But “for now, if only through inertia, Obamacare persists,” Vann R. Newkirk II writes. In other legal matters, Garrett Epps explains the issues around President Donald Trump’s confidence in a presidential self-pardon.

A Heavy Truth: Looking forward to unwrapping a weighted blanket this holiday season, but unfamiliar with the origins of the fad? Weighted blankets were first designed to help children with autism-spectrum disorders cope with sensory processing challenges, writes Ashley Fetters, and the wildly popular comfort item remains a necessary clinical tool for many.

—Haley Weiss and Shan Wang

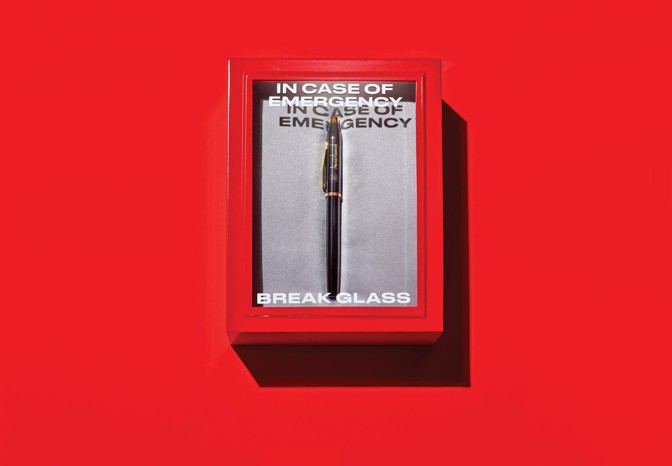

Snapshot What happens after a U.S. president declares a “national emergency,” and what new powers are uncovered for the president after such a declaration? Elizabeth Goitein examines the possibilities, from martial law to the control of all American internet traffic. (Illustration by The Voorhes)Evening Read

What happens after a U.S. president declares a “national emergency,” and what new powers are uncovered for the president after such a declaration? Elizabeth Goitein examines the possibilities, from martial law to the control of all American internet traffic. (Illustration by The Voorhes)Evening ReadFranklin Foer sat down with the New Jersey Senator Cory Booker (and likely 2020 presidential hopeful), a conversation that got at the root of Booker’s political philosophy: it’s all about love, including love for President Donald Trump.

Foer: To pose the obvious and vexing question, can you find love for Donald Trump?

Booker: When I gave a speech at the convention, Trump tweeted something really mean about me, veiledly dark. You know, almost a weird kind of attack on me.

Foer: Who would expect that from a Trump tweet?

Booker: Then next morning, I’m out with Chris Cuomo on CNN and he puts up the tweet. I think he was trying to get a rise out of me. He goes, “What do you have to say to Donald Trump?” I said, “I love you Donald Trump. I don’t want you to be my president; I’m going to work very hard against you. But I’m never going to let you twist me and drag me down so low as to hate you.”

Foer: But not hating Donald Trump is different than actually finding love for Donald Trump.

Booker: My faith tradition is love your enemies. It’s not complicated for me, if I aspire to be who I say I am. I am a Christian American. Literally written in the ideals of my faith is to love those who hate you. I don’t see why that’s so shocking. But that doesn’t mean that I will be complicit in oppression. That doesn’t mean I will be tolerant of hatred.

Something I talked about in my New Hampshire speeches and New Hampshire house parties is the example of Lindsey Graham and what he said during the [Brett] Kavanaugh hearings. One side might call it a rant, one side might call it a noble exposition. But I have to say, I was not happy about it. Obviously he made me angry; obviously I disagreed with what he was saying. But just a few weeks later, he and I are on the phone to the White House. He is defending one of the provisions I want in the criminal-justice-reform bill that’s heading to the floor now, effectively ending juvenile solitary confinement. He was a partner with me.

What Do You Know … About Education?1. Last month, the Stevens Point branch of this U.S. university announced plans to stop offering six liberal-arts majors: geography, geology, French, German, two- and three-dimensional art, and history.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. In a worrying higher-education phenomenon known as this, high-achieving high-school students do not attend the most selective colleges their qualifications suggest they could.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. Now 20 years old, the book The Care and Keeping of You, published by American Girl, is a beloved head-to-toe guide for girls about what topic?

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: University of Wisconsin / Undermatching / Puberty

Dear TherapistEvery week, the psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb answers readers’ questions in the Dear Therapist column. This week, an anonymous reader from New Jersey writes in:

A few years ago, my sister stopped giving my children and me birthday gifts. I continued to send her and her children gifts. For their 14th and 16th birthdays, however, I stopped in response. The gifts themselves are not the issue—it’s totally fine to stop sending gifts (and none of us really needs anything anyway), but I'm wondering what prompted this change since she still sends gifts to my other sister’s kids. She’s never said anything about it.

We did have an argument four years ago, but that was resolved and everything has seemingly been fine for years. But I wonder if she has some issue with me that I’m not aware of. Should I ask her about it? I don’t want her to think she needs to send my kids gifts. That's beside the point. I'm just wondering if there was some message I missed that I should address. Or should I just let it go?

Read Lori’s response, and write to her at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Written by Olivia Paschal (@oliviacpaschal) and Madeleine Carlisle (@maddiecarlisle2)

Today in 5 LinesRepublican Senator Lamar Alexander announced that he would not seek reelection in 2020, setting up Tennessee for its second Senate election in two years after Republican Marsha Blackburn won her seat in November.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo explicitly said for the first time that he supports legalizing recreational marijuana in New York and announced that it would be one of his legislative priorities in early 2019.

Two new reports released by the Senate Intelligence Committee detail how Russian trolls attempted to depress voter turnout among African Americans in the 2016 campaign.

Former FBI Director James Comey testified in a closed-door hearing in front of the House Judiciary and Oversight committees, after already testifying for six hours earlier this month.

A former business partner of Michael Flynn, President Donald Trump’s former national-security adviser, was charged with conspiracy and acting as an agent of a foreign country after lobbying to have a Turkish cleric extradited from the U.S.

Today on The AtlanticThe World in 2019: According to foreign-policy experts, this is what lies in wait for the United States—and the world—in the year to come. (Uri Friedman)

The Future of Obamacare: The landmark health-care legislation was struck down in a Texas court this weekend. Here’s what comes next. (Vann R. Newkirk II)

Love Language: In an interview with Franklin Foer, New Jersey Senator Cory Booker talks about his faith, his potential run for president, and why he’s “leaning even more into” love—even for Trump.

Pardon Me, Sir: What would happen if Trump tried to pardon himself? Garrett Epps breaks down the possible scenarios.

The Future of Farming: A small-dollar provision in the new farm bill strengthens programs for farmers outside the current dominant, aging, white demographic. (Olivia Paschal)

Snapshot Furniture to be moved sits in the hall outside congressional offices weeks before the end of the term, as dozens of outgoing and incoming members of Congress move into and out of Washington. (Reuters / Jonathan Ernst)What We’re Reading

Furniture to be moved sits in the hall outside congressional offices weeks before the end of the term, as dozens of outgoing and incoming members of Congress move into and out of Washington. (Reuters / Jonathan Ernst)What We’re ReadingHow to Win in 2020: The Democrats’ best chance to take the White House is to put forward an economic populist, argues David Leonhardt. (The New York Times)

‘A Trump Personality Cult’: The death of The Weekly Standard marks a turning point in not only conservative media, but also conservative ideology. (Seth Masket, Pacific Standard)

Testing the Waters: Julian Castro, the former secretary of housing and urban development, is thinking about running for president. Could he have a shot at turning Texas blue? (Ryan C. Brooks, BuzzFeed News)

Who’s to Blame?: Paul Ryan is on the conservative speaking circuit blaming everybody but himself for the current state of American politics, writes Tara Golshan. (Vox)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

As the border between the United States and Mexico began to figure more and more prominently in the news cycle, the filmmaker David Freid noticed a consistent blind spot: No one, it seemed, was talking to the people who actually lived there.

He decided to pay a visit to Big Bend National Park, which composes 13 percent of the U.S.-Mexico border. There, he encountered Mike Davidson, the captain of the Rio Grande’s only international ferry.

“But we discovered that the international ferry was a rowboat,” Freid told The Atlantic.

Though no hulking vessel, the modest boat transports 11,000 annual visitors—a feat for which Davidson, whom Freid describes as “a good ambassador between Mexico and the United States,” has been responsible for more than 40 years.

Freid’s short documentary Ferryman at the Wall is the story of two countries that, for the most part, peacefully coexist where it matters most: at the dividing line. “When there’s a fire in Big Bend National Park, residents from Boquillas, Mexico, come up to help fight it,” Freid said. Davidson, an American, has homes in both Texas and Mexico; he speaks Spanish and English fluently. Freid found that this cultural melding was commonplace in the towns adjacent to Big Bend.

“There isn’t just a straight line where one country ends and the other begins,” Freid said. “People’s family and friends extend in both directions. The land on either side of the Rio Grande is identical, and the people are close to identical as well. The two countries bleed into each other.”

Davidson echoes that sentiment in the film. “These countries are entwined more than people could ever imagine,” he says. “Politicians get a lot of mileage talking hard about the border when they absolutely don’t have a clue.”

A man rejected by a woman pops up unannounced at her workplace with roses, asking her to reconsider. Adorable or creepy? The case for creepy would seem easy to make, what with the guy’s violation of space, forcing of a private matter into a communal spectacle, and implication that love can be bought with gifts. In some cases, such a stunt can even be a tell for something more dangerous: “Showing up unannounced” is one of four things listed in an article titled “It’s Not Cute, It’s Stalking: The Warning Signs” on the website of One Love, a nonprofit “working to ensure everyone understands the difference between a healthy and unhealthy relationship.”

Popular culture has other ideas about such gestures, though. Romantic comedies regularly broadcast the desperate-love gambit—Love Actually’s sign at the door, Say Anything...’s boom box over the head—as a rite of passage on the way to a happy ending. Usually, it is men who make the supposedly noble overture; the idea that the story might be flipped led to the subversive TV show Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.