Many historians agree that the North American figure of Santa Claus can be traced back to a monk named Saint Nicholas of Myra, a bearded fourth-century Greek Christian with a penchant for charitable giving. St. Nicholas was presumably the basis for the Dutch Sinterklaas, patron saint of children, who donned a big, red cape and rode around on a white horse to visit children on the name day of Saint Nicholas, the sixth of December. According to folklore, Sinterklaas carried a red book in which he recorded a child’s behavior over the past year as having been good or naughty. Sinterklaas is said to have been slowly transformed into modern-day Santa by 1700s Dutch immigrants in the New World.

“But maybe there’s another story worth telling this season—one about a psychedelic mushroom-eating shaman from the Arctic.” That’s Matthew Salton, whose animated short film, Santa Is a Psychedelic Mushroom, presents a different origin story entirely. It’s a compelling narrative, backed by Harvard professors, anthropologists, and esteemed mycologists alike, and it bears an uncanny semblance to the modern tradition of Santa Claus.

Until just a few hundred years ago, the story goes, the indigenous Sami people of Lapland, a wintry region in northern Finland dense with conifer forests, would wait in their houses on the Winter Solstice to be visited by shamans. These shamans would perform healing rituals using the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria, a red-and-white toadstool fungus that they considered holy. So holy, in fact, that the shamans dressed up like the mushrooms for their visit. Wearing large red-and-white suits, the shamans would arrive at the front doors of houses and attempt to enter; however, many families were snowed in, and the healers were forced to drop down the chimney. They would act as conduits between the spirit and human world, bringing gifts of introspection that could solve the family’s problems. Upon arrival, the healers were regaled with food. They would leave as they came: on reindeer-drawn sleds.

In Salton’s film, the animation is hand drawn; each illustration is traced over at least three times, “depending on how the image moves or morphs from one thing to the next,” Salton told The Atlantic.

Although Salton himself harbors a healthy skepticism about the shamanistic origins of Santa, he believes the inquiry has its own merit. “In my opinion, the connections can’t all be 100 percent true, but they’re surprising and fun to think about,” he said. “My understanding is that most academics who approach the subject do so as a fun exercise and not something to be taken too seriously. That said, I think many would agree it’s important to question and take a deeper look into our shared folklore. Santa consists of an amalgamation of many ideas, traditions, and imagery. My film focuses on just one aspect.”

The animation features interviews with experts on the subject, such as Lawrence Millman, a writer and mycologist who is admittedly not one for holiday cheer. “I hate Christmas,” Millman says in the film. “The shaman comes as a healer or to give advice … we should think in terms of regarding Christmas not as a capitalistic holiday, but a time to think more spiritually about life.”

Over the next week, The Atlantic’s “And, Scene” series will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy cinematic moment from 2018. Next up is Alex Garland’s Annihilation. (Read our previous entries here.)

The denouement of Jeff VanderMeer’s novel Annihilation is Lovecraftian in its sci-fi inscrutability. The main character, an unnamed biologist, descends the staircase of a mysterious underground structure she calls the “tower” and encounters a creature called the “Crawler,” a being that is all but indescribable. H. P. Lovecraft enjoyed writing about monsters that were too terrible to behold, that would reduce anyone who looked at them to a gibbering mess. The Crawler is perhaps slightly less malevolent, but nonetheless difficult to explain: a fungal hodgepodge of people, animal, plants, and things at the center of Annihilation’s surreal “Area X.”

Garland, in his telling, read a galley of VanderMeer’s novel, absorbed it, and said to the author, “I don’t know how to do a faithful adaptation of your book.” The director wasn’t lying—his take on Annihilation is similar in plot setup (a biologist investigates a mysterious zone with an all-female team of scientists), but quite different in many other ways. The movie’s conclusion sees the protagonist, Lena (played by Natalie Portman), encountering some very curious things, including a copy of herself and a glowing, undulating Mandelbulb that was once her fellow explorer Ventress (Jennifer Jason Leigh).

It’s weird. It’s different. But most importantly, the ending doesn’t lend itself to easy interpretations, which was exactly the experience that I sought from Garland’s film (as a big fan of VanderMeer’s writing). Though it was released in February and for the most part wasn’t even seen in theaters outside of America, Annihilation is the kind of studio oddity that seems destined to stand the test of time, partly because of how bold and unusual its ending is. It’s rare for a film this aggressively challenging to make it through the studio net these days, but Annihilation did, and Garland (who had final-cut rights and withstood studio efforts to change the ending) made the most of it.

[Read: A longer deconstruction of the ending of ‘Annihilation’]

The film’s final scene can be broken into two sections: one taking place above ground and the other below, both beautifully scored by Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow’s thrumming score. After Lena treks through the “Shimmer,” an alien environment that was generated on Earth by a meteor strike, she comes upon a lighthouse surrounded by human bones. Inside lies the burned-up corpse of her husband (Oscar Isaac), who journeyed into the Shimmer before her. Down beneath the surface is a chamber that resembles a colossal carapace; there, Ventress suddenly appears and vomits glowing energy into the air before transforming into a giant, phosphorescent object.

Eventually the object morphs, and Lena is challenged by a shiny metallic humanoid that imitates her every move. If she fights it, it fights back. When she lies down, so does it. The sequence is like a plaintive sort of waltz, one that was choreographed by Bobbi Jene Smith and performed by Garland’s frequent collaborator Sonoya Mizuno. It’s frightening, but it’s also sort of funny, a little sad, and, of course, highly metaphorical.

Every member of Lena’s team entered the Shimmer shouldering some sort of trauma. Ventress was dying from cancer, and her demise—a brilliant but terrifyingly rapid deterioration—reflects that. Lena, meanwhile, is wrestling with the loss of her husband (who disappeared on his own mission) and with crippling depression. Portman plays her like a walking ghost, echoing back questions in a monotone; when Lena sleeps with a colleague after her husband vanishes, she seems surprised at herself in the aftermath. In doing battle with her duplicate (the shiny alien eventually adopts a Portman-esque outer layer), her internal conflicts are made literal. The unknowable world of the Shimmer is certainly extraterrestrial, but Garland knows that the most interesting thing about the place is what it reflects about trespassers like Lena. Weaponizing her fears against her is the smartest, and scariest, adaptation decision Garland made.

Eventually, Lena finds a way around the alien: She coaxes it into taking a grenade, destroying her own mimic in order to survive. But the end of the film suggests that she’s been fundamentally altered by the experience (her eyes glow as she returns to the real world). How? Garland doesn’t care much for simple explanations. The final trial of Annihilation is a spiritual and emotional one, beautifully rendered as a dark battle for one’s soul. As the alien double burns to death, it staggers over to the skeleton of Lena’s husband and touches it gently, consuming him in the flames. In letting go of that painful loss, Lena participates in a moment of destruction that is both necessary and strangely moving.

Previously: Black Panther

Next Up: Hereditary

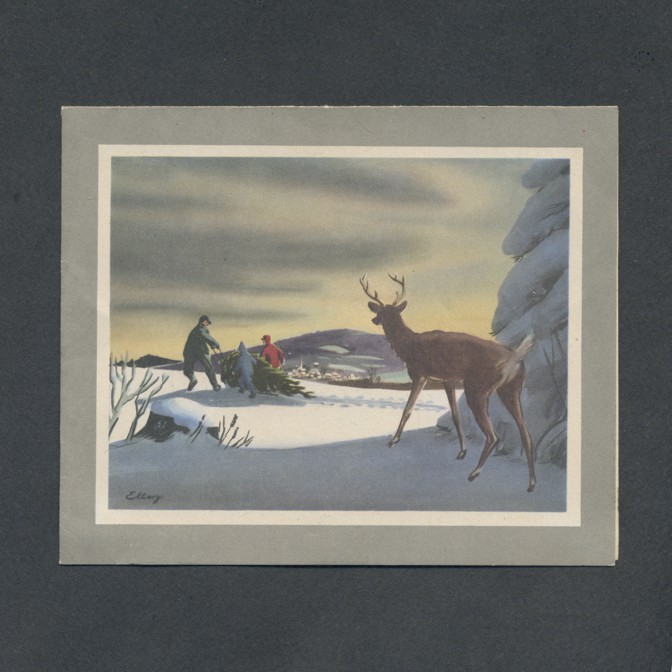

Since publishing its first issue in 1857, The Atlantic has marked 160 Christmases. Contributors, by dint of the magazine’s New England and Christian roots, made a point each year to memorialize the birth of Jesus and the many traditions celebrating it in every section and medium of the publication. For more than 16 decades, there have been myriad articles, stories, poems, book reviews, recipes, art, and even, in the mid-20th century, dozens of annual subscription gift cards.

“Whoever has passed the month of December in Rome will remember to have been awakened from his morning-dreams by the gay notes of the pifferari playing in the streets below,” wrote an unnamed contributor in April 1859, evoking the music of the season. The pifferari, as the article described, were shepherds who came to Rome at Christmastime to play music before shrines of the Madonna and child; these performers, and their songs, were a staple of Decembers in the city.

Eighteen years later, Luigi Monti recalled another Italian Christmas—this one passed in an abbey in Sicily. He detailed how the religious traditions of the holiday bled into the social: how the Christmas Eve service “from time immemorial … has been followed by a reunion at home, with play and dancing till a late hour” and how, on Christmas, after a mid-day sermon, “if the weather was good, the whole population would go wandering through the streets, to cafés and restaurants, which were kept open all night.”

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1948

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1948Other writers traveled still farther than Italy, sharing accounts of winters spent in Africa. Two such accounts, brought back from Ghana’s Dix Cove in 1870 and Egypt’s Assuan in 1895, were distorted by the prejudices of their Western writers; the unnamed visitor to Dix Cove noted the prevalence of “African barbarism” and remarked on the strangeness of “black Christmas” celebrations, while the American essayist Agnes Repplier described some of the wares at an Assuan market as “barbaric” and “absurd.” But both also found aspects of the holiday familiar, and beautiful: dinner parties, drinking, music, gifts.

In an 1885 article, the Scottish author Edmund Noble described a similar experience of familiarity for Western Europeans spending their winter holidays abroad—in Russia. “Perhaps it is at Christmas that the foreign resident usually finds himself most at home in St. Petersburg,” he wrote; and later, in more detail: “Christmas time turns Russian markets into veritable forests, while Christmas Eve fills the streets of St. Petersburg with crowds that, in the purchases they are making for the morrow, bear a striking resemblance to the pedestrians and shoppers one may meet in any German city at the same time of year.”

And, as recalled in a 1910 article, the holiday season in Germany did fit that description. “Here was a whole country where nobody was too big for trees,” wrote Mary D. Hopkins of her first Christmas there: “Everywhere, as far as you could see, those green trees stretched … Green lanes ran to and fro, and in those lanes twinkling lights marked little booths full of wonderful shining things of gold and silver and crystal.”

Thirty years later, Josiah P. Marvel described Germans spending a much more fraught holiday in a Gestapo prison in France during World War II. As a member of the American Service Committee, he helped deliver gifts, a tree, and fruit to the prisoners without family connections, attempting to bring some of the “friendship and love that signify Christmas” to the enemy.

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1964

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1964The American hostages in Iran were offered similar respite in 1979, as Mark Bowden wrote in 2005. Liberal ministers were permitted to visit and hold ceremonies throughout the day for the young prisoners. One, Kathryn Koob, “was profoundly sad to be cut off from her world, isolated from her family and any community of Christians; from familiar Christmas music, the swirl of shopping, cards, parties, and gift-giving,” Bowden wrote. “And yet somehow the holiday became, if anything, more meaningful for her as a prisoner.”

That spirit of camaraderie and mercy was absent from the Hanoi Christmas bombing of 1972, remembered for the American veteran William Broyles upon his return to Vietnam after the war by a local doctor. “I was teaching a class about mitral stenosis when we heard the anti-aircraft guns begin to fire and then the terrible noise of the B-52 bombs coming toward us,” the doctor recounted. He detailed the devastating aftereffects: a collapsed hospital; crushed, rotting bodies; dead students. “But war is war,” he said. “We must go on.”

Back in America, writers described more peaceful and familiar holiday seasons. In her 1864 series on her experience teaching freed slaves on South Carolina’s Sea Islands, Charlotte Forten recalled a Christmas with her young students spent singing, attending church, opening presents, and listening to stories. “It was a wonderful Christmas-Day, — such as they had never dreamed of before,” she wrote. “The long, dark night of the Past, with all its sorrows and its fears, was forgotten; and for the Future, — the eyes of these freed children see no clouds in it.”

An unnamed contributor described another bright-spirited Christmas passed at a Presbyterian minister’s house in 1920. “The approach to Christmas was the usual crescendo, something like a rocket that bursts into multicolored lights as they climax and then falls into darkness,” the writer reflected. “The darkness in our case was the cold and sullen stream of school which surrounded us. Christmas was a luxuriant island, in which magical things were done in the glow of candles and odor of fir trees.”

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1960

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1960“Christmas at the Ranch” in 1933 brought similar joy to the writer Hilda Rose. The isolated locale provided her and her family refuge during the Great Depression; “we are marooned, — shut away in the wilderness,” she wrote, “yet I would rather be here than out where I should have to see the misery and the hopeless eyes of the aged who had been living on carefully invested savings and have lost all.” A young man arrived on her doorstep on Christmas Day, looking for work after leaving behind his own large family and their farm in Canada; to Rose, he seemed “too good to be true—a treasure Santa Claus has brought.”

Katharine O. Wright passed another remote “Mountain Christmas” seven years later in Kentucky where, she wrote, “in row upon row of miners’ shacks, Christmas is reminiscent of many an old country.”

The British journalist Edmund Yates stated in a lecture “that all that the ‘Americans’ knew of Christmas they had learned from, or since the publication of Dickens’s Christmas stories,” wrote the literary critic Richard Grant White in his review of “Some Alleged Americanisms” in 1883. White dismissed this remembered claim as absurd: “The Maryland descendants and representatives of the old Roman Catholic colony of Lord Baltimore, and the New Orleans natives of the same faith, will learn with some surprise that they owed to the Protestant heretic Charles Dickens the birth of the feeling which made Christmas to them a great and solemn festival.” Americans, he argued, had been celebrating Christmas since long before Dickens reached their shore—and, as Wright witnessed decades later, would continue to do so in those old traditions for years to come.

Even so, another Atlantic contributor did laud Dickens’s portrayal of the holiday in A Christmas Carol. “There is not, in all literature,” asserted an 1868 review of the novel, “a book more thoroughly saturated with the spirit of its subject … and there is no book about Christmas that can be counted as its peer.”

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1967

Atlantic holiday gift subscription card from 1967The magazine was less kind to another Christmas classic: “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” the song. Cullen Murphy described it in 1990 as “an unwelcome piece of work not least because its tune, after one or two hearings, takes on the quality of an advertising jingle.” And, he asserted, “Worst still is the way it tells a story … with jaunty moral vacuity.” Murphy preferred the original book, which was “full and rich” and presented the reindeer’s heartwarming story with more character and depth.

Works such as A Christmas Carol and Rudolph that captured that positive holiday spirit, Samuel McChord Crothers wrote in 1906, were important as a counterbalance to the grim literature of evil and disillusion. “At Christmas time those of us who in our journey through the world have found some things which seem to us to be good, and which encourage us to hope for more good farther on, need not be greatly troubled by what is continually being written against our creed,” he contended. “Good-will is not a bit of weak sentimentalism; it is a force actively engaged in righting the wrongs it sees.” In literature, as elsewhere, he argued that good spirit was worth fighting for.

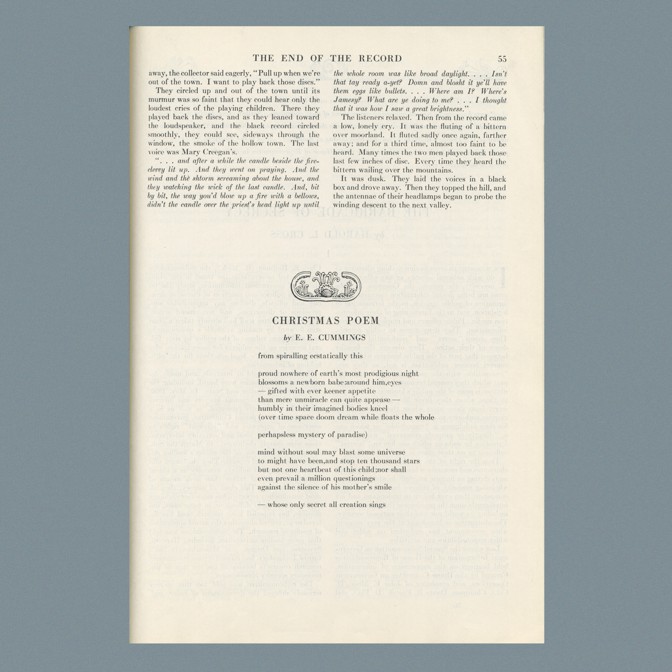

Some of that hope and optimism can be found in e. e. cummings’s December 1956 “Christmas Poem,” in which he offered a mystical portrait of holy birth interspersed with characteristically artful punctuation:

mind without soul may blast some universe

to might have been, and stop ten thousand stars

but not one heartbeat of this child; nor shall even prevail a million questionings

against the silence of his mother’s smile

— whose only secret all creation sings

Annie Dillard provided another magic-tinged, though more natural, take on the holiday in her 1973 poem “Feast Days: Christmas,” which opened, “Let me mention / one or two things about Christmas. / Of course you’ve all heard / that the animals talk / at midnight,” and went on to describe a spiritual exchange of animals, environment, and God.

But the magazine’s Christmas literature was also occasionally shadowed with its own darkness and disillusion. Published posthumously in 1965, Ernest Hemingway’s 1944 “Second Poem to Mary” incorporates an almost prayerlike “Hail to Father Christmas” into a strange, somber reflection on mortality. He concluded:

It is no longer Christmas

And from this hill, bare-topped,

Its flanks covered with Christmas trees,

Many further hills are seen.

More of both sides of Christmas can be found in the archives—dark and bright, melancholy and uplifting. Various lighthearted tidbits can be unearthed, too. In 1949 and 1950, contributors offered elaborate recipes for Christmas cookies and dinner dishes. In 1954, writers turned a satiric eye to holiday cards and catalogs. And today, The Atlantic continues to collect Christmas takes and traditions—including some from its readers.

Last month, The Atlantic asked readers to share their strangest, silliest holiday traditions. The Family section commissioned illustrations for a handful of the responses; we’ve rounded up some of the other weird and wonderful submissions here.

When our children were young, they helped my wife make an “angel” to go on top of the tree. It ended up resembling a chicken more than an angel. So every year, once we’ve completed decorating the tree, we have a Christmas-chicken-placing ceremony where we play a song from the Muppets chickens while placing the chicken on top of the tree. Our kids are now in their early 20s and we still look forward to this tradition.

Dave Carlile

Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Every holiday season my family gathers together to make hundreds of pierogi—traditional Polish dumplings. My great-grandmother used to make them without any kind of recipe, but before she passed away my grandma (whom I call Mimi) spent time with her in the kitchen and was able to get a recipe down. Now it’s become a Pisarczyk-family tradition and everyone from my dad’s side of the family comes together on this one day. There aren’t many times when we are all able to be in the same house together, but the hours we’ve spent rolling out dough, making balls of potato and cheese filling, and eating “noodles” made from the leftover dough strips are some of my favorite memories. We don’t all celebrate Christmas together, but everyone eats the pierogi on Christmas Eve, which gives us a sense of full-family celebration even if we aren’t all sitting around the same table.

Megan Pisarczyk

Midland, Mich.

Beginning last year, my family decided to set certain standards for our get-together at Christmas. We exchanged socks. It was great fun looking at ads and stores to find socks that were unusual or just brightly colored. A few of us cheated and bought slippers.

We also started the tradition of having a theme for each Christmas and dressing accordingly. Last year it was Gilligan’s Island. So me, the mother and oldest, went as Gilligan, an easy costume. This year the theme is The Princess Bride, and I’ll be going as the wife of Miracle Max. My daughter will go as the albino, my granddaughter will go as Buttercup, and the others will be choosing other characters from the movie to represent. The possibilities for future choices are endless.

Doris Bezio

De Pere, Wis.

Our family Christmas traditions have been uniquely different and various from the time our daughter was 4 years old until she was 18. We have done everything from working in soup kitchens in San Francisco feeding the homeless and poor to working in Mexico and Central American countries for charitable causes. We wanted our daughter to grow up knowing real-world conditions outside her comfort zone in the U.S. We never exchanged material Christmas gifts and preferred real-life experiences, which we felt were more valuable and rewarding.

Elina Halstrum

Bainbridge Island, Wash.

Several years ago, my wife and I felt we needed a better way to celebrate or mark the winter season of change. We had become so tired of the materialistic push that feels like such a part of that time. We now celebrate “Turning” during the 12 days from the solstice until the new year. Each year, we decide on a theme and 12 elements of that theme. Then each day we draw from the 12 and discuss ideas related to that element of the theme. The year Barack Obama was elected we chose 12 things we hoped for his presidency. One year we drew angel cards. One year we drew from the list of “Advice From … ” for our focus for the day. This is our 25th year together, and we are talking about using our relationship as the focus, and more specifically identifying things we can do for 10 minutes a day that will enrich our relationship. Each day, we come together and light a candle for that day’s focus and remind ourselves of the days that have come before. Then we both talk about what that day’s issue means to each of us. Then we each write a poem following the simplest form of a cinquain, a five-line stanza. And we read those poems to each other. Those 12 poems are the gifts we give each other each year.

Ruth Langstraat and Roxanne WhiteLight

Kihei, Hawaii

New Year’s Eve is a holiday I closely associate with my dad. My mom would typically be asleep before 10:30 p.m., so the evening was spent eating snacks and watching movies with Dad. Every year, whoever was the oldest and had the darkest hair was to go outside at 11:57 and enter at midnight with a lump of coal in hand to bring prosperity to the household. As my dad went gray at the age of 25, this duty fell to me and my dark-brown curls.

Growing up, I knew the drill; once it was 11:55 I was to put on my coat, mittens, and boots to face the dark northern–British Columbia winter. Once outside, I would find the “coal” in the mailbox (a small rock wrapped in black hockey tape). I knew it was time to knock on the door when I heard the far-off fireworks signifying the arrival of the new year. Dad would then open the door and accept my offering of coal before it was time for bed.

Katherine Benny

Prince George, British Columbia, Canada

My husband is British, so we’ve adopted the custom of eating “snap dragons” on New Year’s Eve at midnight. You need fresh almonds, some cheap brandy, and a wooden bowl (which we line with foil. Why? It will become obvious soon). You put the almonds in the bowl, warm the brandy, and at midnight, turn out the lights, set the brandy on fire with a match, and pour it over the almonds. This creates a gorgeous blue flame. Take turns grasping the flaming almonds in your fingers and tossing them into your mouth. We live in Maine and, if weather permits, we walk the nearby causeway to an island and do this in the snow by the sea, in pitch black, using Sterno to heat the brandy. Magical.

Amy MacDonald

Falmouth, Maine

When I was growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, there was one holiday card that featured an illustration of an apple with a metal spring “worm” that popped out when you opened the card. The card was sent anonymously from one family member to another (it was a very large extended family, too), with no return address, so the sender always knew who would get the card next, but no one ever knew from whom it came! We’d wait for the mail delivery each December to see if this year we were “it.”

Wendl Kornfeld

New York, N.Y.

My family hosts hay rides for our neighbors in the middle of the city. Yep. At the beginning of December, we borrow our family member’s trailer, buy some hale bales (I guess? My stepdad does this part. He might steal them honestly), stuff them in the trailer, and then schedule at least four hay rides before Christmas. People come over to my parents’ house, eat soup, and heat up apple cider with Tuaca (it’s the greatest booze you’ve never heard of). Then we stuff everyone into the trailer with blankets and Santa hats, and our designated driver drives us around the neighborhood to look at Christmas lights. We all have songbooks that are waterlogged packets of printer paper no one thinks to replace, and we sing sloppy carols to lots of victims, er, passersby. People got to expecting our caravan of crazy every year; we singlehandedly started a tradition in our city. Now other people tow trailers, rent brew bikes, and even reserve horse and carriages to roam our neighborhood—which has led to more amazing Christmas lights than ever. It’s a snowball effect (pun intended).

Stephanie Buck

Sacramento, Calif.

It’s a very simple tradition, but we’ve been doing it for more than 30 years now. Every New Year’s Day, we head to the bookstore—Amazon doesn’t count—to buy a new book to start off the new year. That’s it. I used to drive my mother crazy by picking Calvin and Hobbes or Garfield books or books about baseball. She would have preferred me to choose Twain or Dickens or some other great literature. In the end, she was happy that I was reading anything, and eventually I came around to more sophisticated tomes. Our tradition gives you something both tangible (turning the pages) and intangible (the excitement of a new story) to look forward to in the new year. Now that I’m grown and married, I’ve kept up the tradition with my own family, even as it gets harder to find local bookstores open on New Year’s Day.

James Lynch

Baltimore, Md.

Every year, my very-German grandmother from the upstate New York town of Remsen brings a small Peppermint Pig to Christmas dinner. As a family, we place the pig in a small velvet bag and take turns, youngest to oldest, hitting the pig with a small metal hammer until the pieces are broken up enough to eat.

I had always assumed it was at least a somewhat well-known German tradition until my girlfriend and I were talking about it, which ultimately led us to googling the tradition and stumbling onto this New York Times article, which I sent to my grandmother, asking why she never told us more about the history of the pig. Since then, we’ve had a number of conversations via phone and FaceTime about how difficult it has become through generations to separate American and German identities, and what the value is of maintaining one over the other.

Rob Arcand

Durham, N.C.

My mixed-Asian family of nine (an Indian grandfather, a Filipina grandmother, their two daughters, one of the daughters’ white husband, and four grandchildren) was never able to decide on a cuisine for Christmas. So one year we admitted defeat and ordered a truly ridiculous feast of Chinese takeout, lit a fire in the fireplace, and burned the takeout boxes while we opened presents. It’s been a tradition ever since.

Madeline McCue

Minneapolis, Minn.

At first glance, a tamal might seem simple enough: masa dough stuffed with filling, wrapped in a husk or a leaf and steamed. But as those who have made tamales know, their simplicity is a ruse. It’s a process that takes hours and often days to complete, requiring nimble fingers to wrap the palm-sized packages of dough and watchful eyes on them while they steam—an ordeal best left for the holidays.

For many Latinos in the United States, the holiday season is synonymous with tamales. Families gather together to make and eat these beloved packages, often well into the new year. These aren’t the kind that can be picked up in the grocery store’s freezer aisle, though. They’re labors of love for the cooks who make them. Those cooks are often women who grew up learning how to make them, says Zilkia Janer, a global-studies professor at Hofstra University. Tamales haven’t been sold en masse in the way that other holiday foods like turkey and honey-baked ham have, she says, because their value comes from the fact that they’re handmade, and from the memories that they evoke.

“During the holidays, you want to reconnect [to] where you came from or where your ancestors came from,” she says, “meaning that tamales are different not just from country to country, but also from region to region and even from abuela to abuela. So people might not have the skills to make them, but they have the memory of having tasted them. And they know what they should taste like.”

[Read: A briefing on eating tamales]

Those differences are reflected in the variety of tamales available in the United States, thanks to the history of Latinos’ migration to the states. In a way, Janer says, it’s difficult to define what a tamal even is since they can vary so wildly—much like Latinos themselves, tamales are not a monolith. While Mexican Americans in the Southwest often opt for corn-husk-wrapped tamales, those from Central America typically wrap theirs in banana leaves. And while most Mexican and Central American tamales contain corn-based masa, Puerto Rican pasteles don’t use any whatsoever, instead using a combination of ground yautía and green bananas. Tamales’ unifying factor, then, comes from their basic structure and the fact that they’re not an everyday meal, Janer says.

Those game for the herculean task of making them often require an entire team to help assemble them, says Erika Stanley, a chef from Dallas who grew up in Costa Rica making tamales with her family. Each person was assigned a different role: preparing the masa, cooking a variety of meat fillings, softening up the banana leaves, carefully wrapping each tamal, and monitoring them as they cooked. And if you make tamales, you make a lot of them, Stanley says, remembering that her family often ate them from December to January. In this way, it’s inherently a family activity, she says, and a tradition she cherished when she came to the United States. “They are hard to make and they are labor-intensive,” she says. “But it is a part of you that you want to share with others. It’s your love and tradition and your culture, so it is the most wonderful present someone can give you.”

For those who don’t have the time or experience to make tamales, the art of acquiring enough holiday tamales for a family can feel almost like getting black-market goods. In the weeks leading up to Christmas, the phrase “tamale plug” (or dealer) populates the Facebook and Twitter feeds of Latinos across the country, with people begging their friends to give them the name of someone’s mom or grandmother who can set aside a few tamales for them. And you need to find your tamal dealer well in advance—many people start taking orders around Thanksgiving, and those who are late to the game are left behind.

In San Antonio, Juan Rodriguez is one of those “plugs.” He grew up in the area, delivering tamales door-to-door for his mom as a kid, earning him the nickname “Tamale Boy.” When his mom passed away, he continued her tradition and is now a sought-after vendor. Thanksgiving tamales have to be ordered by November 1 and Christmas ones by December 1, he says, and any extras are available on a first-come, first-served basis. He made about 6,000 tamales for the Thanksgiving-season orders, he says, and he expects he’ll make even more for Christmas.

One of the best parts of the job for him, he says, is how many different people he gets to meet on a day-to-day basis. He loves being able to adapt his recipe to different customers’ memories of the tamales of their childhood. “Some people are from the [Rio Grande] Valley, some are from New Mexico and El Paso, and everyone has a different way of how they grew up eating tamales,” he says. His favorite part, then, is figuring out how to make them all happy, practicing until he gets it right: “That’s when I present it to the customers and they bite it and they go, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s what it was like when I was a kid in the Valley or in El Paso.’”

Of course, Latinos don’t have a monopoly on Christmas tamales—like other foods introduced by immigrants, they’ve become staples in other Americans’ holiday-food lineups. While Stanley mostly cooks tamales for her network of Latino friends and family, Rodriguez says that his clientele—white, black, Latino, Asian—reflects the diversity of San Antonio. It’s a kind of reverse integration, Janer says; while people often think of immigrants as being shaped by their new country, the opposite is often happening with their own food. “Latino culture has an impact on the food cultures where they are,” she says. “It’s part of the ongoing history of tamales. They are becoming a part of the food culture and the lives and communities.”

Gabriela Fernandez contributed reporting.

Gilberto Flores had to leave.

A teacher at his school in Jocoro, El Salvador, had just been dismembered by his own students after he was outed as a gay man. Gangs were dumping bodies in the streets around his home. Not long before, Flores had come out to his school as openly gay. His mother, who is still in El Salvador, didn’t think it was safe for him to stay.

He was 14 years old when he left his home in 2012 to make the long trek up to the United States. He spent two weeks on the road going through Guatemala and Mexico, smuggled on buses along with a group of about 10 others who wanted to come to America, all fleeing desperate conditions in Central America. His family had paid smugglers to transport him through those countries up to the U.S. border. That was the “pretty comfortable” part of the trip, he told me.

[Read: Trump’s deal with Mexico could make asylum next to impossible]

But then he came to the Mexican border town of Reynosa, where smugglers had established a station for migrants to congregate before crossing the Rio Grande near McAllen, Texas.

“There were so many people in those houses that you had to sleep on top of each other—literally,” he said. “You got fed twice a day, you were not allowed to leave the premises.” Migrants who attempted to flee were caught and beaten.

Their day to cross the border eventually came. They intended to surrender to American border-patrol authorities on the other side and to seek asylum. The smugglers gave Flores and the others a set of small, flimsy rafts. They didn’t even have paddles—one person was supposed to swim in the water and pull the raft along with him. Things didn’t go as planned.

[Read: Purgatory at the border]

Partway through the crossing, Border Patrol agents showed up to intercept them. “Hide!” someone shouted. The migrants panicked. One immediately dove off the raft, flipping it over and tipping everyone into the water.

Flores had a sweatshirt tied around his neck, and it quickly soaked up water, dragging him down. “I couldn’t actually breathe,” he said, remembering the sensation of drowning.

Before he drowned, a Border Patrol officer pulled him out of the water and asked him how old he was. When Flores replied “14,” the officer turned pale and brought him onshore with the rest of the group of migrants.

[Read: Today’s migrant flow is different]

Flores was now in Border Patrol’s custody. But he was alive—and, most importantly, on American soil.

Flores is one of the thousands of children who came to the United States alone fleeing violence in Central America—a population that the federal government officially classifies as “unaccompanied alien children.” Over 200,000 children—mostly from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—have arrived since 2012, according to the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Almost 41,000 children arrived in 2017 alone.

The great majority, including Flores, go on to seek asylum once they arrive in the United States. Flores was one of the lucky ones. His asylum claim was processed and granted in a matter of weeks after his interview with the Arlington asylum office in 2015.

But now, the Trump administration is actively unraveling ways for asylum-seeking migrant children to stay in the United States. Asylum approvals have plummeted, and the administration wants to deny all asylum claims for all who cross the border illegally—something that advocates are calling an “asylum ban.” A federal judge blocked the policy on November 20, and litigation continues. The federal government announced on December 21 that asylum seekers will remain in Mexico while their decisions are pending, and it is likely that advocates will challenge that policy change as well.

Although asylum has always been difficult for children to win, this outright hostility toward asylum seekers has not always been the case. In 2008, recognizing that unaccompanied migrant children faced specific humanitarian concerns compared with adults, Congress established a channel through the Trafficking Victims Protection Act for unaccompanied migrant children to seek asylum. But the burden is still on the children to argue their case in a way that fits the law’s protections.

It is up to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officer in the asylum interview to assess that claim of persecution, as well as to make the determinations of a protected social group, something that leaves a lot of leeway for the individual asylum officer to determine—and something very hard for a child to understand and properly articulate in an asylum interview without a lawyer.

“What frustrates me the most about how I see the asylum officers doing their job is that they expect applicants to be able to identify themselves as a member of a particular social group,” said Elissa Steglich, who teaches the Immigration Clinic at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

Many children might not even have been told why exactly they were being sent to the United States, especially when an adult made the decision to send them on their journey.

“If a child isn’t given all the information, he or she may think, for example, that the trip was mainly to reunite with family members in the U.S., while the more important and underlying motive may be to escape extortion by a gang,” wrote Matthew Lorenzen, a researcher on unaccompanied Central American migrant children, in an email.

Because immigration law is civil, not criminal, children are not entitled to legal counsel when they go through their asylum interviews or immigration-court proceedings. The Obama administration had allocated $4.5 million annually for the legal representation of migrant children through the Justice AmeriCorps program, but in 2017, the Department of Justice under the Trump administration declined to renew the contracts with immigrant-legal-services nonprofits. Now, fewer and fewer children are getting the legal representation they need.

“Right now, less than half of the kids are getting representation,” explained Jennifer Podkul, the policy director at the nonprofit Kids in Need of Defense, or KIND. “It’s almost impossible for a child to win asylum cases if they’re not represented.”

“Unfortunately, regardless of what the country conditions are, regardless of what the danger is, how much danger the child feels, a child isn’t going to know what’s relevant to an asylum officer,” said Michelle Mendez, the managing attorney of the Defending Vulnerable Populations Project at the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc. “He or she is not going to know how to verbalize even why they might be scared. They might be too traumatized.”

Under the 1951 Refugee Convention, migrants who fear persecution in their home country on specific grounds can petition for asylum or refugee status. Most unaccompanied children argue that they face persecution in their home country due to membership in a particular social group—a family targeted by a gang, for instance. It’s a relatively high legal standard to meet.

“What’s lost in a lot of the debate is how narrow the asylee and refugee definition is,” explained Ruth Wasem, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

The Trump administration has sought to tighten the definition even further. In June 2018, then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued guidance that restricted asylum claims by domestic-violence survivors and victims of gang-based violence.

Relatively few cases have been heard under the new guidance, but advocates like Alexandra Rizio, the senior staff attorney at the Safe Passage Project, a nonprofit in New York City that represents migrant children, expect the decision to restrict asylum. “It’ll be harder to win asylum cases, especially when there is domestic violence,” she said, though she thinks that there is still a path to win asylum cases.

Child-asylum approvals had fallen even before the Trump administration issued its “asylum ban.” An analysis of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services asylum data shows that across USCIS asylum districts, approvals have fallen from a high of 85.1 percent, during the third quarter of 2014, to 28.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018. Only 10.9 percent of all juvenile asylum cases were approved in the Houston, Texas, asylum division this past quarter. As fewer and fewer children have access to proper legal representation, it is possible that the asylum-approval rate could fall further.

The Trump administration’s increasing hostility toward asylum applicants threatens the cases of asylum petitioners like Javier (whose name has been changed because of the sensitivity of his asylum case). Javier’s case has been pending since he came to the United States in 2015, when he was 17 years old.

He was forced to leave El Salvador when a member of Mara Salvatrucha (the gang more commonly known as MS-13) approached him after school one day and started beating him. The gang had already tried to recruit him, which Javier had refused. His mother had previously fled to America to get away from her abusive husband and had been working there for some time. To the gang members, the few American dollars she remitted meant that Javier’s family had money. As a result, his family was singled out for extortion, and potentially worse.

To get her children away from the gangs, Javier’s mother paid smugglers an exorbitant amount—$5,000, almost one and a quarter the average salary in El Salvador—to take him and his sister to America. He spent three months shifting between different buses and walking the entire route from El Salvador, through Honduras and Mexico, to the Texan border. To the smugglers, the children were just cargo.

“Sometimes [the smugglers] don’t even give you any food or water or anything,” he told me through a translator.

He crossed the border at Hidalgo, Texas, in May 2015, and then surrendered to border-patrol authorities. His sister was placed into expedited removal and deported three days later. Javier stayed, though, and was placed in youth detention in San Antonio for two months, until he was released at the end of June 2015 to reunite with his mother in Seattle.

His case has been pending since then, despite multiple, grueling interviews over Skype with the asylum office in San Francisco. Javier at least has a lawyer, Shara Svendsen, to help navigate all of the asylum proceedings. She told me that some interviews went for as long as four hours at a time.

Yet Javier can’t go back to El Salvador because he fears that the gangs would kill him. “I’m afraid they’ll kill me or that they’ll do something bad to my life … I can’t go back to El Salvador or Honduras,” he said. “News travels fast. When they find out you’re back, at any moment, others might want to come find you and do something bad to you.”

In a May interview with NPR, Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen acknowledged low asylum-approval rates, saying that “at the end of the day, only 20 percent are actually given asylum by judges, meaning 80 percent of the people coming here are either fraudulently claiming it, which is breaking the law, or they do not have a case that fits within our statutory framework.”

Advocates disagreed, saying that the situation on the ground differed entirely from the secretary’s assessment. Gui Stampur, the deputy executive director of the Safe Passage Project, responded that “the secretary of homeland security should meet and interview asylum seekers and hear their stories, and then she will learn that that’s not the case.”

Other advocates attributed the administration’s hostility to asylum to political posturing. Omar Jadwat, the director of the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, argued that “very little of what [the administration] has said even begins to grapple with the reality that these are people coming to the United States to seek protection from persecution.”

Officials at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

A denial of asylum status is not the end of the line for most children. They’ll get what immigration lawyers call “another bite at the apple,” a curious culinary analogy for a deadly serious issue, in which they can have their case heard before an immigration judge, and perhaps might have access to other forms of legal relief like protection under the convention against torture, or a special legal status for children abandoned by their family.

Still, their chances are not that much better in immigration court, where judges face increasing political pressure from the Trump administration to clear cases, despite an increasingly large case backlog. Over the past year, 56,498 immigration-court cases, and about 23 percent of all juvenile immigration-court cases, ended in a removal order. These orders typically end in a deportation if immigrants lose their appeals.

According to Jennifer Podkul, the policy director at KIND, there is no government program for the safe repatriation of children to their home country. Instead, the federal government has some partnerships with NGOs in an attempt to safely repatriate children, all in line with what they call the “best interests” of the child.

Not all children have access to those repatriation programs, though, and for those unlucky enough to fall through the cracks, the “government drops them off in a return shelter in the country,” Podkul explained.

As a result, they might still end up like Javier’s sister, who remains back in the family’s hometown in El Salvador, at the mercy of gangs like MS-13.

The Trump administration rails against the “loopholes” in the system that allow migrants to stay, arguing that the migrants will be a drain on American taxpayers. But actual cases tell a different story. Take Gilberto Flores, the gay youth who left El Salvador and came to the U.S. after the openly gay teacher at his school was murdered. Three years after he was granted asylum, he is now attending college in Washington, D.C., with the aspiration of becoming a nutritionist.

In the meantime, the children will keep on coming, left at the mercy of an administration intent on shutting the door on them.

If Beale Street Could Talk, the 1974 James Baldwin novel, begins with a bittersweet announcement of new life. “Alonzo, we’re going to have a baby,” Clementine “Tish” Rivers tells her fiancé from across the cold glass of a New York City jail’s visitation room. Tish narrates the story, so the reflection that follows is in her voice. “I looked at him. I know I smiled,” she says. “His face looked as though it were plunging into water. I couldn’t touch him. I wanted so to touch him.” For much of the novel, their hands can’t cross the glacial barrier. But Tish and her beloved nonetheless find a way to remain entwined.

The new Barry Jenkins–directed film adaptation gently renders Baldwin’s expansive, embattled vision of black love. As in the novel, the story follows the 19-year-old Tish (KiKi Layne) as she navigates life following the 22-year-old Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt’s (Stephan James) incarceration on false rape charges. Even as they face entrenched discrimination and mounting legal hurdles, the love between the two never wavers. It is singular in its expression, but it doesn’t stand alone. A constellation of love surrounds them.

[Read: How Barry Jenkins turned his James Baldwin obsession into his next movie]

Jenkins’s If Beale Street Could Talk is a gorgeous, enveloping film—and one of its most poignant triumphs is how vividly it captures the depth and complication of intimacy among its black characters. Tish and Fonny are its nucleus, but the film pays rare, urgent attention to the contours of familial love, too. Tish’s struggle to free Fonny from the clutches of the racist criminal-justice system is not one the young woman endures on her own. Her mother, Sharon (Regina King), reassures her in their shared domestic space, and fights for Tish outside the bounds of their home. Her father, Joseph (Colman Domingo), takes on the duty of securing alternative revenue streams to fund Fonny’s legal assistance and support the pair’s unborn child. Her sister, Ernestine (Teyonah Parris), offers Tish solace and—when necessary—riposte.

Depictions of black love are not impossible to find, but the Jenkins adaptation translates Baldwin’s text with a tenderness often shunned by major studio films. The movie doesn’t revel in the spectacle of its characters’ pain, and indeed scrubs some of Baldwin’s grit from its visuals. Where other stories might have pitted the fantasy of Tish and Fonny’s love, Beale Street paints a luminous portrait of a delicate balance: Their love undergoes duress, but this is a story, above all, of joy.

The film foregrounds the people who grant Tish and Fonny’s youthful romance the buttressing it needs to weather the kinds of difficulties that black people must endure. They do so with grace, humor, and style. They do so the only way they know how. In its attention to the galvanized chorus around its central characters, Beale Street offers a sweeping affirmation of the love Baldwin felt for his own people—even and especially in times of hardship.

Tatum Mangus / Annapurna Pictures

Tatum Mangus / Annapurna PicturesCapturing the intricacy and intimacy of black families, biological or chosen, is not a new pursuit for Jenkins. Moonlight, the film that was clumsily awarded Best Picture at the 2017 Oscars, traced the experiences of a gay black boy in desperate need of kinship. Based on the story by the playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney, Moonlight follows the protagonist Chiron across three stages of his life. Played with remarkable grace by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevante Rhodes, Chiron spends much of his early years searching for belonging. After his mother (Naomie Harris) mocks her son for his feminine expressions and effectively abandons him amid her struggles with addiction, Chiron is wholeheartedly embraced by Juan (Mahershala Ali), a local drug dealer, and his girlfriend, Teresa (Janelle Monáe). Juan and Teresa’s love for Chiron doesn’t just nourish him; it also keeps him alive.

[Read: ‘Moonlight’ is a film of uncommon grace]

As in Moonlight, the love that Beale Street’s characters have for one another is impossible to extricate from the larger societal forces acting on them. Their love is heavy. Because of how violently the criminal-justice system has interfered in the course of their lives, Fonny and Tish do not have the luxury of relying on their families for quotidian forms of support: They cannot enjoy newlywed bliss or ponder whose parents will provide the furnishings in their shared home. Tish and Fonny’s fears about their impending parenthood do not end with the question of what foods to feed their child. The child, whom Tish eventually names for his father, is the product of the couple’s deep bond, as well as a primary source of familial anxiety.

Fittingly, Beale Street explores the power—and limits—of parental love in situations of structural injustice. One of the film’s most gutting sequences is that in which Tish’s mother travels to Puerto Rico. Intent on finding the woman who’s cooperated with a racist police officer’s identification of Fonny as her rapist, Sharon knows her journey could be the catalyst for her future son-in-law’s freedom. Beyond the financial cost of the trip, she bears a staggering emotional burden. To confront a woman who’s levied so grievous a charge is no small psychological hurdle. In her layered (and Golden Globe–nominated) performance, King imbues Sharon with fear, righteous responsibility, and desperation. At the root of all these emotions is the love she feels for Fonny—and more important, for her daughter.

This same thread connects stellar performances from Domingo and Parris as Tish’s father and sister, respectively. Even as Joseph and Ernestine banter with warmth and humor, the stakes of Tish and Fonny’s jeopardized future are never far away. Ernestine is overprotective of Tish, not just because Tish is her baby sister, but also because she knows the dangers a pregnant young black woman faces. In an early scene that finds Tish nervously announcing her pregnancy to Fonny’s relatives, Ernestine springs into action when Fonny’s mother (Aunjanue Ellis) curses the unborn child. Jenkins’s visual hallmarks—soft-lit tension, tightly framed shots of actors’ faces—lend a revelatory sense of immediacy to the connections and conflicts between the two families.

The fissures between—and within—the families are as instructive as the necessary cohesion. In Baldwin’s novel, Fonny’s family resented Tish partly because she is darker than he is. The Hunt family’s colorism, like the criminal-justice system’s punitive bias, is a dangerous wedge. (Asked about the decision to cast James as Fonny, whom Baldwin wrote as a light-skinned man, Jenkins told the Los Angeles Times, “Stephan came in and his work was so strong and I thought, ‘If you’re going to flip this one way, it’s kind of OK to flip it this way, because we so rarely flip it this way.’”) Beale Street’s families are neither paragons of blissful coexistence nor pathology-driven unions. They struggle with vices both human and spiritual. Still, they need each other.

Baldwin didn’t champion a quixotic vision of love so much as he insisted that white supremacy’s far-reaching harm heightened its stakes. Racism seeps into the most intimate corners of his black characters’ lives. Amid its dire effects, the care these individuals show one another must be more than powerful enough to serve as a kind of sustenance. It becomes an exhortation and a privilege. Or, as the author’s niece, Aisha Karefa-Smart, said at the film’s New York City premiere in Harlem’s historic Apollo Theater,“The act of loving while black is a revolutionary act. It’s an act of resistance to love under the conditions with which we live, to raise children, to maintain family, and just continue the resistance and stay strong.”

If Beale Street Could Talk is unequivocal in its celebration of this pragmatic, buoyant phenomenon. The film, like the novel, doesn’t slip into hokey affirmations. But in the face of injustice, tenderness can be an essential lifeline. “If you trusted love this far, don’t panic now,” Sharon tells Tish at one point. “Trust it all the way.”

Holiday parties were right around the corner, and I needed a cover story. I didn’t feel like admitting to casual acquaintances, or even to some good friends, that I drive a van for Amazon. I decided to tell them, if asked, that I consult for Amazon, which is loosely true: I spend my days consulting a Rabbit, the handheld Android device loaded with the app that tells me where my next stop is, how many packages are coming off the van, and how hopelessly behind I’ve fallen.

Let’s face it, when you’re a college-educated 57-year-old slinging parcels for a living, something in your life has not gone according to plan. That said, my moments of chagrin are far outnumbered by the upsides of the job, which include windfall connections with grateful strangers. There’s a certain novelty, after decades at a legacy media company—Time Inc.—in playing for the team that’s winning big, that’s not considered a dinosaur, even if that team is paying me $17 an hour (plus OT!). It’s been healthy for me, a fair-haired Anglo-Saxon with a Roman numeral in my name (John Austin Murphy III), to be a minority in my workplace, and in some of the neighborhoods where I deliver. As Amazon reaches maximum ubiquity in our lives (“Alexa, play Led Zeppelin”), as online shopping turns malls into mausoleums, it’s been illuminating to see exactly how a package makes the final leg of its journey.

There’s also a bracing feeling of independence that attends piloting my own van, a tingle of anticipation before finding out my route for the day. Will I be in the hills above El Cerrito with astounding views of the bay, but narrow roads, difficult parking, and lots of steps? Or will my itinerary take me to gritty Richmond, which, despite its profusion of pit bulls, I’m starting to prefer to the oppressive traffic of Berkeley, where I deliver to the brightest young people in the state, some of whom may wonder, if they give me even a passing thought: What hard luck has befallen this man, who appears to be my father’s age but is performing this menial task?

Thanks for asking!

[Derek Thompson: Amazon’s HQ2 spectacle isn’t just shameful. It should be illegal.]

The hero’s journey, according to Joseph Campbell, features a descent into the belly of the beast: Think of Jonah in the whale, or me locked in the cargo bay of my Ram ProMaster on my second day on the job, until I figured out how to work the latch from the inside. During this phase of the journey, the hero becomes “annihilate to the self”—brought low, his ego shrunk, his horizons expanded. This has definitely been my experience working for Jeff Bezos.

During my 33 years at Sports Illustrated, I wrote six books, interviewed five U.S. presidents, and composed thousands of articles for SI and SI.com. Roughly 140 of those stories were for the cover of the magazine, with which I parted ways in May of 2017. Since then, as Jeff Lebowski explains to Maude between hits on a postcoital roach, “my career has slowed down a little bit.”

This proved problematic when my wife and I decided to refinance our home. Although Gina, an attorney, earns plenty, we needed a bit more income to persuade lenders to work with us. It quickly became clear that for us to qualify, I would need more than occasional gigs as a freelance writer; I would need a steady job with a W-2. Thus did I find myself, after replying to an indeed.com posting for Amazon delivery drivers, emerging from an office-park lavatory a few miles from my house, feigning nonchalance as I handed a cup of urine to the attendant and bid him good day.

Little did I know, while delivering that drug-test sample, that this most basic of human needs—relieving oneself—would emerge as one of the more pressing challenges faced by all “delivery associates,” especially those of us crowding 60. An honest recounting of this job must include my sometimes frantic searches for a place to answer nature’s call.

To cut its ballooning delivery costs—money it was shelling out to UPS and FedEx—Amazon recently began contracting out its deliveries to scores of smaller companies, including the one I work for. Amazon trains us, and provides us with uniform shirts and hats, but not with a ride. Before 7 a.m., we report to a parking lot near the warehouse where we select a vehicle from our company’s motley fleet of white and U-Haul vans.

I’m an Aries, so it stands to reason that I’m partial to Dodge Ram ProMasters. I like their profile and tight turning radius: That’s key, since we make about 100 U-turns and K-turns a day. Problem is, most of the drivers in our company—there are about 40 of us—share my preference. The best vans go to drivers with seniority, even if they show up after I do. Before it was taken out of service for repairs, I was often stuck with a ProMaster that had issues: Side-view mirrors spiderwebbed; the left mirror held fast to the body of the van by several layers of shrink-wrap. The headlights didn’t work unless flicked into “bright” mode, which means that when delivering after dark, I was blinding and infuriating oncoming motorists.

I drove that beast on my worst day so far. After a solid morning and early afternoon, I glanced at the Rabbit and sighed. It was taking me to that fresh hell that is 3400 Richmond Parkway, several hundred apartments set up in a mystifying series of concentric circles. The Rabbit’s GPS doesn’t work there, the apartment numbers are difficult to find, and the lady in the office informed me that I couldn’t leave packages with her. She did, however, hand me a map resembling the labyrinth of ancient Greece. I spent an hour wandering, ascending flights of stairs that took me, usually, to the incorrect apartment. By now deep in the hole, with no shot at completing my appointed rounds for the day, I set a forlorn course for my next stop at the nearby Auto Mall. That’s when I heard a thud-thud-thud from the area of my right front tire, which was so old and bald that it had begun to shed four- and five-inch strips of rubber, which were thumping against the wheel well.

[Read: Amazon is invading your home with micro-convenience]

Although it was only 4 p.m., I called it quits. Some days in the delivery biz, the bear eats you. But I got some perspective back at the lot, where a fellow driver named Shawn told me about the low point of his day. A woman had challenged him as he emerged from her side yard—where he’d been dropping a package, as instructed. “What are you stealing?”

“That sucks,” I said. “I’m sorry that happened to you.”

“It's cool,” he told me. “I called her a bitch.”

For both days of my safety training, I sat next to and befriended Will, who now shows up for work wearing every Amazon-themed article of clothing he can get his hands on: shirt, ball cap, Amazon beanie pulled over Amazon ball cap. I found that odd at first, but it makes good sense. If you’re a black man and your job is to walk up to a stranger’s front door—or, if the customer has provided such instructions, to the side or the back of the property—then yes, rocking Amazon gear is a way to protect yourself, to proclaim, “I’m just a delivery guy!”

That safety training, incidentally, is comprehensive and excellent. After two days in the classroom, all of us had to pass a “final exam.” It wasn’t a slam dunk. In my experience, however, some of the guidelines Amazon hammers home to us (seat belts must be worn at all times; the reverse gear is to be used as seldom as possible; driveways are not to be blocked while making deliveries) must be thrown overboard if we’re going to come close to finishing our routes.

And there’s the bathroom issue.

The Google search Amazon driver urinates summons a cavalcade of caught-in-the-act videos depicting poor saps, since fired, who simply couldn’t hold it any longer. While their decision to pee in the side yard—or on the front porch!—of a customer is not excusable, it is, to those of us in the Order of the Arrow (my made-up name for Amazon delivery associates), understandable.

Before sending me out alone, the company assigned me two “ride-alongs” with its top driver, the legendary Marco, who went out with 280 packages the second day I rode shotgun with him, took his full lunch break, did not roll through a single stop sign, and was finished by sundown. Marco taught me to keep a lookout not just for porch pirates—lowlifes who swoop in behind us to pilfer packages—but also for portable toilets. In neighborhoods miles from a service station or any public lavatory, a Port-a-John, or a Honey Pot, can be no less welcome than an oasis in the desert. (The afternoon I leapt from the van and beelined to a Honey Pot, only to find it padlocked, was the closest I’ve come to crying on the job.)

[Read: The authors who love Amazon]

Delivering in El Sobrante one day, I popped into a convenience store on San Pablo Avenue. I bought an energy bar, but that was a mere pretext. “I wonder if I might use your lavatory,” I asked the proprietor, a gentleman of Indian descent, judging by his accent, in a dapper beret.

A cloud passed over his face. “You make number one or two?”

“Just one!” I promised. He inclined his head toward the back of the store, in the direction of the “Employees only” bathroom.

After thanking him on my way out, I mentioned that I was new at Amazon, still figuring out restroom strategies.

“Amazon drivers, FedEx drivers, UPS, Uber, Lyft—everybody has to go.”

But where? When no john can be found, when the delivery associate is denied permission to use the gas-station bathroom, he is sometimes left with no other choice than to repair to the dark interior of the cargo bay—the belly of the beast—with an empty Gatorade bottle.

It was late afternoon on a Monday when I may or may not have been forced to such an extreme. I was dispensing packages on Primrose Lane in Pinole, and I remember thinking, afterward: Aside from the fact that my checking account is overdrawn and I’m 30 deliveries behind and the sun will be down in an hour and I’m about to take a furtive whiz in the back of a van, life really is a holiday on Primrose Lane!

Pinole, incidentally, is the hometown of the ex–Miami Hurricanes quarterback Gino Torretta, a great guy who won the Heisman Trophy in 1992. I covered him then, and a few years later when he was playing for the Rhein Fire in the NFL’s World League. Gino and I hoisted a stein or two at a beer hall in Düsseldorf. Some of the American players were having trouble enunciating the German farewell, auf Wiedersehen. To solve that problem, they would say these words as rapidly as possible: Our feet are the same!

Performing my new job, I’m frequently reminded of my old one, whether it’s driving past Memorial Stadium in Berkeley, where I covered countless Pac-12 games, or listening to NFL contests during Sunday deliveries. I’ve talked and laughed with many of the players and coaches and general managers and owners whose names I hear.

Sitting in traffic one damp December morning, I turned on the radio to hear George W. Bush eulogizing his father. His speech was funny, rollicking, loving, and poignant. It was pitch-perfect. In the summer of 2005, after returning from the Tour de France—cycling was my beat during the reign of Lance Armstrong—I was invited, along with five other journalists, to ride mountain bikes with W. on his ranch in Crawford, Texas. The Iraq War was going sideways; 43 needed some positive press. I jumped at the chance, even though I loathed many of his policies. In person, Bush was disarming, charming, funny. (These days, compared with the current POTUS, he seems downright Churchillian.) I wrote two accounts, one for the magazine, another for the website. Got a nice note from him a couple weeks later.

Lurching west in stop-and-go traffic on I-80 that morning, bound for Berkeley and a day of delivering in the rain, I had a low moment, dwelling on how far I’d come down in the world. Then I snapped out of it. I haven’t come down in the world. What’s come down in the world is the business model that sustained Time Inc. for decades. I’m pretty much the same writer, the same guy. I haven’t gone anywhere. My feet are the same.

When I’m in a rhythm, and my system’s working, and I slide open the side door and the parcel I’m looking for practically jumps into my hand, and the delivery takes 35 seconds and I’m on to the next one, I enjoy this gig. I like that it’s challenging, mentally and physically. As with the athletic contests I covered for my old employer, there’s a resolution, every day. I get to the end of my route, or I don’t. I deliver all the packages, or I don’t.

That’s what I ended up sharing with people at the first Christmas party of the season. It felt better, when they asked how I was doing, to just tell the truth.

This is also true: Gina and I got approved for that loan last week, meaning that our monthly outlay, while not so minuscule that it can be drowned in Grover Norquist’s figurative bathtub, is now far more manageable, thanks in part to these daily journeys which I consider, in their minor way, heroic.

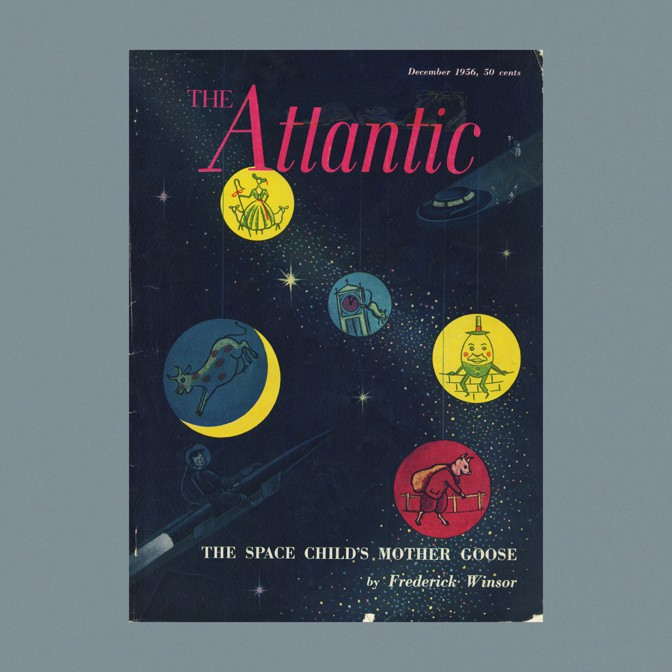

Over the past 160 years, The Atlantic has published the work of some of the world’s most notable poets, from Walt Whitman to Emily Dickinson to Pablo Neruda. In the last years of his prolific career, e. e. cummings joined their ranks, contributing three poems to the magazine in the 1950s. His “Christmas Poem,” printed in December 1956, was the last to appear. The poem presents a modernist take on the familiar story of Jesus’s birth, showcasing cummings’s characteristic free verse and artful syntax while evoking the mystical wonder of the holiday. The issue’s cover, featuring “The Space Child’s Mother Goose,” captured the same sense of unconventional nostalgia. — Annika Neklason

If Becky Sharp were alive in contemporary America, she would almost certainly be working in Donald Trump’s White House. It’s too easy to imagine William Makepeace Thackeray’s grifter antiheroine slapping on an Ann Taylor shift dress and pearls to lavishly praise the president on CNN, only to spin her way to a seven-figure tell-all and a prominent perch on the speaking circuit. As Thackeray wrote in his 1848 novel, “Vanity Fair is a very vain, wicked, foolish place, full of all sorts of humbugs and falsenesses and pretensions,” even though—impossibly!—he’d never even heard of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner.

So there’s something almost comforting about Amazon’s new seven-part adaptation of Vanity Fair, whose opening credits position Becky (played by Olivia Cooke) on a carousel, spinning round and round and going nowhere. Such is the nature of human frailty, the series suggests; things were ever thus, and ever will be. Thackeray subtitled his most enduring book as “A Novel Without a Hero,” and there’s some misanthropic pleasure to be drawn from his parade of imperfect characters, especially during the season of goodwill to all men.

In part, that’s because their self-serving subterfuges are totally transparent. The center of gravity in Vanity Fair has always been Becky, a brilliant and beautiful orphan who scams her way to the upper echelons of society, only to fall all the way down again. In the opening scene of the series, Becky is being dismissed as a French teacher at a girls’ boarding school for her habitual insouciance. (“You forget your station, Miss Sharp.” “I do, yes, daily, and most sincerely.”) While packing her things, she appeals to the tender heart of Amelia Sedley (Claudia Jessie), kicking off a cycle that persists throughout the rest of the story: Becky finds new marks and manipulates them until she either outstays her welcome or dreams up an even better con.

[Read: The Atlantic’s review of Thackeray’s ‘Vanity Fair’—from 1865]

In Cooke, this Vanity Fair has an actor who revels in Becky’s scheming and her ambition (the last major adaptation, starring Reese Witherspoon, felt the need to make Becky more sympathetic, neutering one of literature’s great female characters in the process). Cooke, instead, plays up Becky’s nastier instincts to the hilt, faux-weeping and flirting and breaking the fourth wall with wry faces whenever she’s in the middle of a particularly shameless charade. In contrast to the saintly and insipid Amelia, Becky is both cheerfully callous and much more fun to spend time with.

The show’s writer, Gwyneth Hughes (whose film The Girl, an examination of Alfred Hitchcock’s treatment of Tippi Hedren, preceded the #MeToo movement by five years), also underlines to what extent Becky’s character is a product of her circumstances. A woman in the early 19th century without money or family had limited options with which to improve her lot. Cooke’s Becky, meanwhile, is both fiercely clever and determined that her trajectory will only go up. In another era, those kinds of qualities would present her with numerous options, but amid the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars, Becky’s only recourse for self-improvement involves manipulating others, mostly men.

This being a British period drama (Vanity Fair was co-produced with the British channel ITV), this means that there’s a murderer’s row of actors filing up to feature in Becky’s maneuvers. Martin Clunes plays Sir Pitt Crawley, the uncouth landowner who hires Becky as a governess and immediately wonders how to make her his third wife. Frances de la Tour plays Sir Pitt’s sister, Matilda, a grotesque harridan who—as one of Becky’s charges puts it—is “the richest lady in the whole wide world, and her will is not yet written.” Anthony Head finds levels of pantomime-like evil in Lord Steyne, an exceedingly wealthy and powerful marquis who prizes Becky as yet another possession to be paid for and owned.

What Thackeray made clear is that Becky is far from the only villain in the piece. In the series, Sir Pitt grins lavishly when his wife falls down the stairs; before even ascertaining her condition, he’s racing toward Becky. The women and men who occupy high society are boorish and despicable to a fault; even Amelia tends toward awfulness in her single-minded obsession with her husband, George (Charlie Rowe).

Vanity Fair, Sebastian Faulks has written, deconstructs the idea of novelistic heroism, forcing readers to sympathize with Becky by rendering everyone around her even more unlikable. With Becky, Faulks argues, “Thackeray makes explicit for the first time the rift between real-life and literary morals by showing that the highest virtue a fictional character can possess is interest.” Cooke’s radiantly grasping, delightfully devious Becky proves his thesis, and then some.

OS MILITARES NORTE-AMERICANOS insistem há muito tempo que mantêm uma “leve presença” na África. Também existem relatos de propostas de retirada de forças de operações especiais e encerramento de atividades de tropas no continente, devido a uma emboscada ocorrida em 2017 no Níger e a um crescente foco em rivais como a China e a Rússia. Mas, em meio a tudo isso, o Comando dos Estados Unidos na África (Africom) falhou em fornecer informações concretas sobre suas bases no continente, deixando em aberto a pergunta sobre quais seriam as reais dimensões da atuação americana.

No entanto, documentos da Africom obtidos pelo Intercept através da Lei de Liberdade de Informação oferecem uma brecha única para a extensa rede de destacamentos militares americanos na África, incluindo locais previamente secretos ou não confirmados em pontos cruciais como a Líbia, o Níger e a Somália. O Pentágono diz que as reduções de tropas na África serão modestas e realizadas ao longo de vários anos e que nenhum destacamento será fechado como resultado de cortes de pessoal.

De acordo com um briefing elaborado em 2018 por Peter E. Teil, conselheiro científico da Africom, a constelação de bases militares inclui 34 locais espalhados pelo continente, com grandes concentrações no norte e no oeste, assim como no Chifre da África. Essas regiões, não surpreendentemente, também foram alvos de diversos ataques de drones americanos e ataques de infantaria de menor impacto nos últimos anos. Por exemplo, a Líbia – alvo de missões de infantaria e ataques de drones, mas para a qual o presidente Trump disse não ver nenhum papel dentro das forças armadas americanas no ano passado – é local de três postos militares até então não revelados.

“O plano de posicionamento do Comando dos EUA na África é feito para garantir acesso estratégico a locais-chave em um continente caracterizado por grandes distâncias e infraestrutura limitada”, disse o general Thomas Waldhauser, comandante da Africom, ao Comitê das Forças Armadas do Congresso neste ano, embora sem fornecer dados precisos sobre o número de bases. “Nossa rede de posicionamento permite encaminhar testes de tropas para fornecer flexibilidade operacional e respostas adequadas a crises envolvendo cidadãos ou os interesses americanos sem passar a ideia de que o Africom está militarizando a África.”

Segundo Adam Moore, professor assistente de geografia na Universidade da Califórnia em Los Angeles (UCLA) e especialista na atuação militar americana na África, “está ficando mais difícil para os militares americanos afirmarem plausivelmente que têm uma ‘leve presença’ na África. Só nos últimos cinco anos, foi estabelecido o que talvez seja o maior complexo de drones do mundo no Djibuti – Chabelley – que está envolvido em guerras em dois continentes, no Iêmen e ainda na Somália.” Moore também apontou que os Estados Unidos estão construindo uma base de drones ainda maior em Agadez, no Níger. “Certamente, para pessoas vivendo na Somália, no Níger e no Djibuti, a noção de que os EUA não estão militarizando seus países soa muito falsa”, disse.