Depois de chocar no Brasil o ovo da serpente, ou do fascismo, o ano de 2018 partiu para o esculacho antes de se despedir. Chocou os ovos de uma espécie que, em sua versão com violência além das palavras, a história supunha extinta: a dos galinhas-verdes. Na virada de novembro para dezembro, militantes autoproclamados integralistas afanaram e queimaram bandeiras antifascistas. Regozijaram-se com a aventura que propagandearam como “ação revolucionária”.

No dia 10, começou a circular um vídeo que mostra 11 homens, aparentemente brancos, encapuzados. Eles se apresentam com o nome fantasia “Comando de Insurgência Popular Nacionalista”, componente de uma certa “grande família integralista brasileira”. Contam que surrupiaram três bandeiras com mensagens contra o fascismo afixadas na fachada do casarão onde funciona o Centro de Ciências Jurídicas e Políticas da UniRio (Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro).

Pisam as bandeiras “Antifascismo”, do curso de administração pública, e “Não ao fascismo”, do direito. Um porta-voz lê o manifesto com a denúncia de que “nossa juventude é ensinada a se insurgir contra a pátria”. A consequência das alegadas lições seriam “drogados”, “homossexuais militantes”, “ateus materialistas”, “pedófilos”, “comunistas” e “escravos do banqueirismo internacional”. Na parede do local da gravação, coabitam uma bandeira do Brasil e uma com o sigma, letra do alfabeto grego que foi símbolo da Ação Integralista Brasileira (AIB). O vídeo se encerra com o “ritual de queima das bandeiras”, num simulacro tropical de encenações da Ku Klux Klan.

“Faixa com mensagem contra o fascismo afixada no Centro de Ciências Jurídicas e Políticas da UniRio, depois de três bandeiras serem furtadas e queimadas.

Foto: Foto: Mário Magalhães

Os direitistas fanáticos se inspiram na AIB, organização de massas que, na década de 1930, mobilizou 400 mil militantes em 1.123 núcleos. Seus simpatizantes somavam milhões. Fascinada com o nazifascismo europeu, mimetizava-o em ideias, alegorias e adereços. Em vez da suástica, desenhou o sigma. Os extremistas alemães gritavam “Heil, Hitler!”; os integralistas adotaram o tupi “Anauê!”

Os fascistas italianos trajavam camisas pretas, como um afamado magistrado-político brasileiro faria no século vindouro; os da AIB escolheram outra cor, por isso eram conhecidos como “camisas-verdes” – seus antagonistas os esculhambavam como “galinhas-verdes”.

Depois de uma batalha a pólvora e porrada entre sigmoides e uma frente antifascista, em outubro de 1934, o humorista Barão de Itararé tripudiou: “Um integralista não corre; voa”. Os ladrões das bandeiras repetiram no vídeo a velha saudação galinácea, com o braço estendido para o alto e para a frente. É cópia quase idêntica da saudação romana, horizontal, dos adeptos de Mussolini.

“Avessos ao liberalismo econômico, os integralistas desde sempre se alinham aos liberais no essencial.”Os grupúsculos integralistas em atividade no Brasil apoiaram Jair Bolsonaro contra Fernando Haddad. Na manifestação de 21 de outubro na avenida Paulista, o líder de uma tal Frente Integralista Brasileira ecoou a antiga divisa “Deus, Pátria e Família”. Em seu discurso, Victor Emanuel Vilela Barbuy disse que o integralismo “não se confunde com o fascismo italiano”. Deve ser por isso que seus correligionários ideológicos queimaram bandeiras anti… fascistas.

Ao elogiar a indicação do professor Ricardo Vélez Rodríguez para o Ministério da Educação do próximo governo, o escritor Olavo de Carvalho derreteu-se: “Se você falar de integralismo brasileiro, ele sabe tudo”.

Avessos ao liberalismo econômico, os integralistas desde sempre se alinham aos liberais no essencial: a defesa da propriedade privada dos meios de produção (nos anos 1930, o caráter da propriedade era questão cara à esquerda no Brasil e no mundo). A racista AIB cultivava o antissemitismo, sobretudo o chefe de suas milícias, o escritor Gustavo Barroso. Idem o dirigente número um, Plínio Salgado, também escritor.

Pouco depois da batalha da praça da Sé, que provocou ao menos seis mortes em 1934, Plínio demonizou, no jornal A Offensiva: “Declarei solenemente a guerra contra o judaísmo organizado. É o judeu o autor de tudo. (…) Fomos agora atacados, dentro de São Paulo, por uma horda de assassinos, manobrados por intelectuais covardes e judeus. Lituanos, polacos, russos, todos semitas, estão contra nós”.

Nova faixa antifascistaA crise do liberalismo estimulou a multiplicação dessa gente oito, nove décadas atrás. A AIB influenciou de modo decisivo a história ao fornecer a Getulio Vargas um pretexto, o falso “Plano Cohen”, para o presidente dar um golpe de Estado em 1937 e sacramentar sua condição de ditador.

Foram integralistas personagens de destaque da República que anos mais tarde romperiam com seus valores do passado e rumariam para o centro e a esquerda, como o bispo dom Hélder Câmara, o jurista Goffredo da Silva Telles Junior e o estadista San Tiago Dantas.

Em reedição histórica, os torvelinhos econômicos do final da primeira década do século 21 propulsionaram a ascensão de movimentos aparentados com o fascismo em vários recantos do mundo. A eleição de Bolsonaro se vincula a esse cenário.

As bandeiras foram levadas da UniRio, no bairro carioca de Botafogo, em 30 de novembro. Haviam sido desfraldadas em outubro, como protesto contra decisões judiciais que proibiram iniciativas semelhantes em outras instituições de ensino superior. Depois do vídeo com a incineração, a comunidade universitária abriu uma nova faixa antifascista.

A volta dos ditos integralistas comprometidos com “ações revolucionárias” é mais um episódio grotesco da temporada. O Brasil caminha, como de costume, entre a tragédia e a comédia. O ano foi impiedoso. Já deu para a bolinha dele. Vaza, 2018!

The post A volta dos integralistas: até os ovos dos galinhas-verdes este ano chocou. Vaza, 2018! appeared first on The Intercept.

Noivas costumam atrasar em casamentos. Mas a noiva do PRTB, o general Hamilton Mourão, não é assim. Ele chegou pontualmente às 20h, o horário marcado no convite, para o jantar em comemoração aos 25 anos do partido – ao qual se filiou em março deste ano e se tornou a principal aposta ao se eleger vice-presidente ao lado de Jair Bolsonaro.

Tal qual uma noiva, o vice-presidente eleito foi conduzido mesa a mesa para saudar os convidados ao lado de dois companheiros orgulhosos: Levy Fidélix, o presidente do PRTB, e Alvaro Dias, senador do Podemos derrotado na corrida presidencial deste ano.

No ápice da noite, o general foi levado ao palco montado no centro da Casa Petra, luxuoso salão de festas de Moema, bairro de classe média alta em São Paulo. Estava em frente a uma tela com sua foto, uma bandeira do Brasil e a frase “Meus heróis NÃO morreram de overdose”, referência à música que, sem a negativa, se tornou famosa na voz de Cazuza. Discursou por sete minutos. Neste tempo, foi fotografado, filmado e ovacionado por deputados e senadores eleitos, militares, empresários e ruralistas, todos ávidos para se aproximar e tirar uma selfie.

No discurso, ele agradeceu por ter sido acolhido na “família do PRTB” e falou sobre a necessidade de aprovar reformas da previdência e tributária, “senão em 2022 o governo fecha”. Encerrou com uma frase de efeito: “Vai ser difícil. Mas, aos melhores, as missões mais difíceis”. Aplausos. O casamento foi selado.

Nenhum dos cerca de 200 convidados do jantar tinha dúvidas de que estava perto do próximo presidente do Brasil. E esta pessoa era Mourão. Bolsonaro mal foi citado durante toda a festa.

Em uma mesa ao lado do palco estava sentado o general Paulo Assis, ex-comandante de Mourão no Exército em duas ocasiões e amigo de longa data. Bebericando latinhas de Heineken, o militar da reserva acenava com orgulho todas as vezes em que era mencionado nos discursos. Estava sendo celebrado por ser o responsável por duas façanhas: levar Mourão para a política, filiando-o ao PRTB; e fazer a ponte para que ele se tornasse vice de Bolsonaro.

Venerado pelos convidados da festa, Mourão prestou reverência apenas a Assis e Fidélix, em sinal de lealdade. Com Assis, comportou-se com o respeito e a intimidade de um filho para com o pai.

Fui levada até Assis, seu mentor, por Fidélix – ambos são amigos de longa data. Eu havia perguntado como foi a negociação para que Mourão, disputado por vários partidos, escolhesse a sua legenda, pequena e pouco expressiva – nas eleições deste ano não conseguiu eleger nenhum deputado, nem mesmo o criador do partido. “O culpado é aquele senhor ali”, me disse Fidélix, o característico bigode preto tremendo de orgulho.

General Assis demonstrou animação para contar a história. Ao longo da conversa, ia me mostrando fotos e mensagens no celular, de modo a provar o que dizia. Eram imagens dele e de Mourão servindo juntos. “Veja, que jovem”, me apontava o rosto de um Mourão aos 30 e poucos anos, de óculos de sol, em meio a um grupo de militares. Em outra, os dois estavam lado a lado na selva amazônica. As fotos haviam sido enviadas a ele pelo próprio vice-presidente por WhatsApp.

Quando perguntei o que esperava de Mourão no governo, a resposta veio firme: “o Mourão vai ser presidente da República”. Em 2022 ou antes – caso “algo” aconteça com Bolsonaro. “Tudo pode acontecer. Ele é o vice, é o único que foi eleito. Os ministros todos podem sair, ele não. Vai ficar até o último dia”, vaticinou.

Assis ocupa posição de destaque na equipe de transição do governo, que vem se reunindo em Brasília, para tomar pé da situação atual e planejar os próximos quatro anos. Foi indicado da cota pessoal de Mourão, assim como Fidélix. Ele se considera “conselheiro” do vice-presidente. “Quando ele me perguntar ‘qual será a sua posição [no novo governo]?’, eu vou falar que sou conselheiro”.

Aos gritos – pois estávamos ao lado da banda country que animava o jantar –, o ex-comandante me contou que Bolsonaro sondou Mourão para ser o seu vice há dois anos, na época em que o militar passou à reserva e se tornou conhecido por suas falas corrosivas contra o PT e semi-intervencionistas.

A frase que ficou mais famosa era sobre uma possível intervenção do Exército na política brasileira: “Ou as instituições solucionam o problema político pela ação do Judiciário, retirando da vida pública esses elementos envolvidos em todos os ilícitos, ou então nós teremos que impor isso”. Isso ocorreu em 2017, quando o presidente Michel Temer estava às voltas com denúncias no Congresso. Mourão foi chamado a se explicar e, cinco meses depois, passou à reserva.

Mourão se mostrou interessado, mas o convite acabou ficando em banho-maria. Em abril deste ano, Fidélix procurou Assis para que convencesse Mourão a se lançar presidente pelo PRTB. Disse que iria abrir mão da própria candidatura porque acreditava na força do general.

Em uma reunião a três, Mourão negou o convite porque já havia se comprometido com Bolsonaro. Foi convencido por Assis a seguir um caminho alternativo: se filiaria ao PRTB para ficar na chamada ‘regra três’. Estavam contando que a candidatura de Bolsonaro não iria decolar, ou ele seria impedido de concorrer, e então Mourão poderia assumir o espaço deixado por ele.

“Falei [pra Mourão]: ‘eu acho que o Bolsonaro não vai se eleger, por causa do caso da Maria do Rosário e tal’ [o presidente eleito responde a dois processos no Supremo Tribunal Federal por ter dito à deputada gaúcha que que não a estupraria porque ela “não merecia”]. Falei pra ele: ‘Mourão, dispute a presidência se o Bolsonaro não concorrer. Porque não é bom ter dois candidatos a presidente militares. Se o Bolsonaro cair, nós apoiamos você’”, disse Assis. No dia seguinte, ele e Mourão se filiaram juntos ao PRTB.

O 5º na filaPouco tempo depois, Assis encontrou Bolsonaro em um aeroporto. Ele também foi comandante do presidente eleito durante um curto período de tempo. Perguntou a ele se o convite a Mourão ainda estava de pé. “Ah, não, chefe, eu não posso abrir mão de 45 milhões de evangélicos, que é o Magno Malta”, Bolsonaro teria respondido a ele, citando o senador pelo Espírito Santo, íntimo de líderes evangélicos como Silas Malafaia. Informou que iria chamar Mourão para ser ministro da Defesa.

Malta, que chegou a ser chamado por Mourão de ‘elefante branco na sala’, acabou não aceitando o convite para ser vice. Também minguaram as tratativas com o general Augusto Heleno, com a advogada responsável pelo impeachment da presidente Dilma Rousseff, Janaína Paschoal, e com o “príncipe” Luiz Philippe de Orleans e Bragança, parte do que restou da família real no Brasil. O nome de Mourão foi tirado novamente da cartola na véspera da convenção do PSL, em que a chapa de Bolsonaro deveria ser oficializada. Mas ainda havia resistência dentro do PSL.

“O PSL não queria o Mourão”, disse Assis. “O Mourão é estrela.” Perguntei três vezes o que ele queria dizer com isso, mas ele se esquivou: “Ah, não importa”. Depois mudou de assunto.

Ainda de acordo com ele, Bolsonaro teve que ameaçar renunciar à candidatura caso seu partido não aceitasse o general como vice. Acabou dando certo no último momento para o registro da chapa.

“O Mourão me ligou 7h da manhã no dia da convenção. ‘Chefe, acabei de ser convidado para ser o vice do Bolsonaro. E não consigo falar com o Levy’. Eu falei: “se o Bolsonaro ou o [Gustavo] Bebianno não falarem com ele, não vai fechar’”, contou. Mesmo como civil, o dever de hierarquia militar mandava que a negociação fosse feita com o presidente do partido. Sem isso, Mourão estaria desrespeitando a autoridade.

Bolsonaro estava desde cedo tentando formalizar o acordo com Fidélix, mas o celular dele estava desligado. Conseguiu localizá-lo no telefone da esposa. Isso aconteceu pouco antes do início da convenção, às 9h do dia 5 de agosto. Na festa, Assis aparece no palco ao lado de Mourão, Bolsonaro, Bebianno e Fidélix.

Em seu discurso durante a festa de sexta passada, o vice-presidente eleito também falou sobre a costura do acordo com o PRTB. “Meu amigo Paulo Assis, meu comandante, me apresentou o Levy. E aí estabelecemos um pacto. Muito bem, Levy, eu entro no seu partido. Seu partido é de retidão, de honestidade. O Levy diz: ‘é limpo’. E a nossa única visão é que caso o Bolsonaro necessitasse do nosso apoio, nós estaríamos juntos”.

Durante todo o tempo em que conversamos, ficou claro que Assis não confia na capacidade de Bolsonaro de resistir até o último dia de governo. Quanto mais disputar a reeleição em 2022. Ele diz que o seu pensamento reproduz o da classe militar, que apoia Bolsonaro, mas com reservas, por causa de seu temperamento belicoso.

Punição em caso de corrupçãoAo chegar ao jantar, Mourão participou de uma reunião com lideranças por cerca de 20 minutos. Depois não teve mais sossego. Não conseguiu sentar-se à mesa e nem comer os aperitivos que estavam sendo servidos (ceviche de peixe branco, tapioca com mel e canudinho de carpaccio).

Consegui conversar com ele por alguns minutos, de pé, no meio do salão. Perguntei quais seriam seus primeiros atos como presidente, já que irá ocupar o lugar de Bolsonaro ainda em janeiro, quando o presidente deverá se ausentar para fazer uma cirurgia. “Vou manter as ordens em vigor. Nada mais do que isso. Não vou fazer nada de minha iniciativa. Vou manter aquilo que ele tiver determinado”, disse, em tom respeitoso.

Também lhe perguntei se ele defende punição caso algum integrante do governo esteja envolvido em escândalos de corrupção. “O presidente já disse isso, que defende a punição. E eu também já disse”, respondeu. Perguntei se isso valia mesmo se os envolvidos fossem o filho do presidente, ou o próprio, como vem se anunciando o caso do motorista Fabrício Queiroz – a convenção aconteceu oito dias depois de uma reportagem do jornal o Estado de S.Paulo ter revelado que o ex-funcionário de Flávio Bolsonaro fez movimentações suspeitas de R$ 1,2 milhão, em um ano, e depositou parte para a primeira-dama Michele Bolsonaro. “O presidente já disse isso”, repetiu.

Mourão disse ainda não saber quem do círculo pessoal do presidente deseja vê-lo morto, como foi dito por Carlos Bolsonaro. “Sinceramente, não sei. Tem que perguntar pro filho dele”, irritou-se. Logo foi puxado para tirar fotos com apoiadores. Foi embora da festa cedo, sem comer nem beber. Nem mesmo chope, que gosta de tomar em momentos festivos.

Dias de glória para o PRTBA ambição dos perretebistas se tornou palpável. Fidélix afirma que, pela primeira vez, ele e sua equipe estão sendo ouvidos pelos integrantes do novo governo. Acredita que desta vez suas ideias sairão do papel. Uma delas, a mais famosa, é a do aerotrem. O trem-bala que vai ligar várias capitais do país é o mote de campanha de Fidélix desde que formalizou o PRTB, em 1994. “Eu não vou te dar uma frase para você colocar na manchete, mas estamos discutindo mobilidade urbana, sim.”

Com a boa popularidade de Mourão, o presidente do partido estima que conseguirá a adesão de pelo menos mais 10 deputados eleitos. Com isso, acredita que irá superar as limitações da cláusula de barreira, norma que restringe a atuação de partidos que não atingiram um índice mínimo dos votos nacionais, e com isso voltar a ter acesso a recursos do fundo partidário e de tempo de propaganda na TV – até novembro o partido arrecadou R$ 4.192.229,20, segundo dados do Tribunal Superior Eleitoral.

No fundo, este era o real motivo do evento: paparicar Mourão para atrair possíveis pretendentes à legenda. Ao lado do vice-presidente eleito no palco do salão de festas, Fidélix mal continha as lágrimas de emoção.

No jantar dos 25 anos do partido, um vídeo mostrou a trajetória da sigla: do começo apoiando Jânio Quadros, ainda como Movimento Trabalhista Renovador, à participação na campanha de Fernando Collor, da qual Fidélix foi assessor. Jânio e Collor são os grandes ídolos do político.

Mesmo contente com o presente de sucessos inesperados, O PRTB olha para o futuro: seu novo trunfo é um recauchutado Alvaro Dias. O senador deve formalizar a adesão ao partido – o 9º de sua carreira – em breve. Ele foi apresentado no evento como “a voz do partido no Senado” e recebeu o boas-vindas de parte dos convidados.

No que depender de Dias, será um embarque silencioso. Durante a campanha, ele atacou Jair Bolsonaro duramente. Foi flagrado em um vídeo chamando o adversário de “bandido”. Quando me aproximei para falar sobre os novos ares, ele se negou a me receber. “Não estou falando com ninguém desde a eleição e não vou falar até fevereiro. O silêncio fala mais alto. O silêncio é retumbante.”

The post ‘O Mourão vai ser presidente da República’. Um drink com o mentor do vice de Bolsonaro appeared first on The Intercept.

If I told you that there are two major efforts on the left to reform the pharmaceutical industry, and one relies on market competition while the other establishes a publicly run office to manufacture prescription drugs — to control the means of production, so to speak — you might assume that the first comes from capitalist-to-her-toes Sen. Elizabeth Warren and the second from honeymooned-in-the-USSR Sen. Bernie Sanders.

It’s actually the opposite.

Warren introduced legislation on Tuesday with Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., that would create an Office of Drug Manufacturing within the Department of Health and Human Services. That office would have the authority to manufacture generic versions of any drug for which the U.S. government has licensed a patent, whenever there is little or no competition, critical shortages, or exorbitant prices that restrict patient access.

Last month, Sanders and Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., released their own bill to tackle high drug prices, which would require the government to identify any excessively priced drugs (relative to an international index of list prices) and grant a license to private companies to provide competition with a generic version.

The two bills from Warren and Sanders, who are both likely running for president, are actually complementary efforts that deal with different elements of a system that results in Americans paying more for medications than anywhere in the industrialized world. And they reflect a broader attack on the industry from multiple angles.

“Sanders-Khanna and Warren-Schakowsky are two absolutely complementary bills,” said Alex Lawson of Social Security Works, who has worked extensively on drug prices and was involved in both efforts. “It’s important that you’re seeing multiple, transformative big ideas.”

The Sanders-led legislation seeks to reform the monopoly patent system for prescription drugs, which virtually assures high prices and incentivizes the exclusive drugmaker to restrict competition. But the bill relies on a functioning generic drug market that can drive down prices by mass-producing alternatives that steal customers from brand-name treatments.

About 90 percent of all prescription drugs filled are for generic medications. But recent events have revealed that the generic market is also broken. A 2017 National Bureau of Economics Research paper found that generic competition has weakened over time, as fewer firms compete to make alternatives. By 2016, 40 percent of all generics were made by a single manufacturer.

A Government Accountability Office report identified price spikes of 100 percent or more in the generic drug market in one out of every five drugs studied between 2010 and 2015. There is even an active investigation into cartel behavior among 16 different generic drug manufacturers, which allegedly divvied up the market and fixed prices for more than 300 drugs.

This trend toward monopoly providers of generics creates fragile supply chains that can lead to widespread drug shortages in the event of a disruption, something that almost never happens in a well-functioning, wealthy market economy.

Even with multiple generic options, the effect on prices can be illusory. Last month, Teva Pharmaceuticals, a powerful generic drug company, released a generic version of the EpiPen, the price spirals of which have angered patients. But the Teva-made generic costs the exact same amount as a generic EpiPen released by Mylan, maker of the brand-name drug.

Warren’s bill, the Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act, attempts to address that market failure by having the government pick up the slack. The Office of Drug Manufacturing would acquire rights to manufacture generic drugs or contract them to be manufactured by an outside entity. The legislation explicitly states that those generic drugs must be offered at a “fair price” that covers manufacturing and administrative costs while ensuring patient access. The office could strip a contractor of its ability to make and sell the drug if the price point is too high. Proceeds for these sales would go back to covering agency costs, making it a self-sustaining entity.

The government would also be authorized to manufacture active ingredients for medications. This has become a problem, as major drug companies routinely deny rivals samples of their products, which are used in testing to determine whether the generic is an equivalent treatment.

One drug is listed specifically: Generic insulin treatments would have to be produced within the first year of the legislation’s passage. Prices for insulin have skyrocketed in recent years and shortages are common.

“In market after market, competition is dying as a handful of giant companies spend millions to rig the rules,” Warren said in a statement. “The solution here is not to replace markets, but to fix them.”

Except the means to fix those markets is a government-directed option that puts the Department of Health and Human Services into the pharmaceutical manufacturing business. That’s the primary action in the legislation that allows competition to take root and prices to fall. In this sense, competition policy can work hand in hand with targeted nationalizations or public options.

Another section of the bill highlights Warren’s preoccupation with the notion that personnel matters as much as policy. Former drug company lobbyists would be banned from holding the position of director of the Office of Drug Manufacturing under the proposed legislation, as would any senior executive of a drug company subject to regulatory enforcement for wrongdoing.

Advocates generally welcomed the concept of a public drug manufacturer. “Anyone who is serious about controlling costs and ensuring more patients have access to life-saving drugs should be supporting this legislation,” said Richard Master, chair of the Business Initiative for Health Policy, in a statement.

But some experts believe that more work must be done to reform the entire supply chain for prescription drugs. Phil Zweig, a former journalist who works with Physicians Against Drug Shortages, believes that group purchasing organizations, or GPOs — collections of hospitals that contract to provide medical supplies and medications — are at the heart of the exorbitant pricing and shortages. GPOs are a key gatekeeper for drugs administered at hospitals. “Generic drugmakers simply stop making the drugs if they don’t get a sole-source contract,” Zweig said. “It’s a winner-take-all game.”

GPOs have an exception to the anti-kickback statute that allows them to give exclusive contracts to drug companies in exchange for cash, some of which flows back to hospital executives and administrators. Zweig wants to remove the safe harbor. “All we’re trying to do is remove obstacles to competition,” he said.

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, which negotiate prices for drugs sold in pharmacies on behalf of health plans, have also been accused of skimming off the top and artificially creating higher drug prices. The Trump administration has proposed taking away the anti-kickback safe harbor for PBMs.

Warren spokesperson Ashley Woolheater agreed that “there is bad behavior up and down the supply chain,” adding that this bill specifically focuses on the generics and active pharmaceutical ingredients markets.

“It’s going to take a multi-pronged effort,” said Lawson. “This is not a silver bullet, it’s just one piece of it.”

The post Elizabeth Warren Plan Would Allow the Government to Manufacture Its Own Generic Drugs appeared first on The Intercept.

GAP, FRANCE—In a wood-paneled courtroom in this small town in the French Alps, a local judge dealt a hefty setback last week to the European Union’s treasured principle of open borders, one that has underpinned the bloc. And to do it, she fell back on a law that dates back to one of the darkest periods in European history.

In sentencing two immigrants’-rights activists to jail time and handing suspended sentences to five others, Isabelle Defarge, the judge, concluded a case that has pitted volunteers from a shelter for immigrants and asylum seekers against an anti-immigration group. To do so, she relied on a provision of French immigration law—based on a 1938 decree on “the policing of foreigners”—that makes it a crime to help a foreigner enter, circulate, or reside in France illegally. In the process, the case has come to symbolize a wider tension across the continent between advocates of open borders and far-right populists pushing countries to close in on themselves.

The story began in April, when the anti-immigrant group Génération Identitaire kicked off “Defend Europe,” a protracted effort to police France’s border with Italy and prevent immigrants from crossing the frontier. Wearing matching blue windbreakers with Defend Europe written on the back, around 100 activists patrolled mountain trails in trucks, surveilled the woods via helicopter, and placed a massive banner on the mountains that read, in English, Closed border. You will not make Europe your home. No way. Back to your homeland.

[Read: It’s the right wing’s Italy now]

Local residents said Génération Identitaire activists posed as police officers to intimidate and forcibly return immigrants to Italy—which could constitute a violation of the law criminalizing “interference with a state function.” Five asylum seekers interviewed by a researcher with La Cimade, an advocacy group, even claimed that police had collaborated with Génération Identitaire. An investigation into the allegations against the group is underway, but no charges have yet been filed. The police have denied all of the claims made against them.

When volunteers at a shelter for immigrants and refugees in Claviere, a small Italian city on the border with France, caught wind of Génération Identitaire’s plans, they decided to act. The day after Defend Europe began, at least 100 pro-immigrant activists, some of whom were shelter volunteers, marched across the border to Briançon, a critical entry point for the more than 7,000 immigrants and refugees who have arrived from Italy since July 2017, according to Refuge Solidaire, the only welcome center in Briançon. “We’re going to liberate the border!” they yelled as they headed past a police post in a peaceful rally.

Soon afterward, French police and the local prosecutor in Gap opened an investigation into the demonstration; the prosecutor charged seven of the volunteers, who would become known as the “Briançon Seven,” with violating the ban on helping foreigners enter the country illegally.

By upholding an antiquated law and pursuing legal action premised on the idea of a closed border between France and Italy, officials are sending a signal that “it’s legitimate to, in a situation on the border where fundamental rights are being violated, side against the people trying to defend those rights,” Vincent Brengarth, one of the defense attorneys for the Briançon Seven, told me. More broadly, he said, the case hints at the idea that Europe can “reestablish border [controls] in order to undermine solidarity with migrants.”

[Read: A stranded migrant rescue boat reveals the depths of the EU’s crisis]

The very fact that the trial took place at all is a victory for the popular far-right political movements that have used migration and, critics allege, systematic racial profiling to further their cause across the Europe Union. Far-right parties have been vaulted into governing coalitions in Austria, Hungary, and Italy, while centrist governments elsewhere have moved to the right. This has been the case in France, where many on the left fear that President Emmanuel Macron, despite his image as a guarantor of liberalism, is advancing a rightward agenda on migration.

In the courtroom in Gap, those anxieties—over the widening gap between French law and values and the mainstreaming of far-right views in Europe—were palpable.

In April, the prosecutor, working with the police, opened an investigation into whether the Briançon Seven had used the rally to help immigrants enter France illegally. Although during the trial he alleged that they had shepherded in approximately 20 people—a number based on media reports from the march and videos taken by locals—his own investigation did not corroborate that number. The police were only able to confirm that one of the participants had entered the country illegally under the shield of the protestors. The defense argued that the allegation and the inflated estimate were grounded in racially profiling the demonstrators.

The defendants argued that Defend Europe was part of an ongoing hardening of police practices around the border, notably in Briançon, where officers regularly conduct identity checks at the train station, on public transportation, and around town. They maintained that their goal was not to facilitate the illegal entry of undocumented immigrants, but to protest the growing militarization of the border. “We couldn’t just let Génération Identitaire parade like that in our mountains,” Benoît Ducos, one of the defendants, testified.

The Briançon Seven are not the first to face criminal charges for assisting immigrants under the provision based on the 1938 law. In February 2017, a court convicted a farmer, Cédric Herrou, for allegedly helping immigrants reside in France illegally. But in July, France’s highest constitutional court ruled that because Herrou had acted for humanitarian purposes, charging him—even for an illegal act—would violate the French constitutional principle of “fraternity.” On December 12, additional charges against him were dropped on this basis.

Although Herrou was originally prosecuted under the same law as the Briançon Seven, the dropped charges were limited to facilitating residency and circulation; the humanitarian exemption does not yet apply to helping someone enter the country. In the case of the Briançon Seven, the defense argued that the progressive softening of the law should influence their sentencing, and that even if the prosecutor could prove they used the rally to bring in immigrants, the situation on both sides of the French-Italian border would have given them humanitarian reasons to do so.

Much of the increased enforcement the Briançon Seven were protesting was spurred by the terrorist attacks on the Bataclan music hall, a soccer stadium, and bars around Paris in November 2015. Following those assaults, the government declared a state of emergency and reintroduced border controls. Although the state of emergency has since been lifted, border controls have remained in place, and were in place during Defend Europe. But those enhanced security measures, which were recently extended through April 2019, were a response to terrorism—not a measure to control migration. Absent a clear link between migration and terrorism, the defense argued, recent border controls should not justify a strict application of the law penalizing those who help immigrants enter illegally, particularly in light of the constitutional court’s decree on humanitarian exemptions earlier this year. (European citizens, not immigrants or refugees, were behind the majority of attacks committed on French soil since 2015, including the recent attack in Strasbourg.)

Much of this tightened border enforcement, however, has impacted immigrants and asylum seekers. The Briançon Seven’s attorneys referenced a report published by Amnesty International in October that documents routine violations of immigrants’ rights by French police at the border. This includes the theft of valuables from immigrants, high-speed chases on dangerous mountain roads that often lead to serious injuries or even death, and a practice known as “migrant dumping,” in which French police routinely return immigrants to Italy, including minors, without examining individual cases. This can undermine an individual’s right to seek asylum or access child-protection services.

[Read: A nonbinding migration pact is roiling politics in Europe]

Immigrant and refugee advocates fear that Macron is fostering a political environment conducive to these practices. A controversial new immigration law, which takes effect in January, will make it tougher to apply for asylum and curb rights to appeal rejected claims—provisions the far-right National Rally party (previously the National Front) supported. The law is among other moves on migration that have earned Macron, who defeated the far-right firebrand Marine Le Pen in last year’s election, few friends in the disillusioned left. This year, the center-left magazine L’Obs published a controversial cover showing the president behind barbed wire, with the caption “Welcome to the country of human rights.” The issue featured prominent writers and intellectuals denouncing the government’s asylum policy.

By upholding the charges against the activists, Génération Identitaire, for its part, considers Defend Europe a success. Romain Espino, the group’s spokesman, said it is considering a similar operation on the southern border with Spain—now the preferred route for immigrants into France, with Italy’s border all but walled off and winter compounding the risks of a journey through the Alps.

“When the state sees a group of young people who have the courage to block the border and prevent illegals from passing,” Espino told me proudly, “they see what’s possible.” By the end of Generation Identitaire’s two-month operation, he recalled, border police had received more robust reinforcements that they had been requesting for months, and “thanked” Génération Identitaire for its assistance. “We successfully pressured the government,” he beamed. “For us, that’s a victory.”

Former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn on Tuesday got an unpleasant lesson on the difference between politically effective arguments and legally astute ones. Backed by an array of well-wishers including President Trump, and buoyed by widespread conservative arguments that the FBI had violated his rights, Flynn walked into a federal courtroom in Washington hoping for the probationary sentence that Special Counsel Robert Mueller had recommended. Instead he was threatened with jail by a furious United States District Judge Emmet Sullivan, who accused him of selling America out and forced him to retreat from his evasions. Flynn’s lawyers hastily agreed to delay the sentencing until March 2019 so that he might strive to cooperate further with the Special Counsel and perhaps work off the custodial sentence that Sullivan was clearly contemplating.

This may have been a shock to Flynn, but it was predictable to everyone who understands that federal court is neither Twitter nor a cable news show.

Nobody wants to be charged with a federal crime, but if you must, you want the deal Flynn got. He was the first to cooperate in the Special Counsel investigation in December 2017, and got the first cooperator’s prize: a plea to a single count of lying to the FBI, an offense usually resulting in a sentence of probation. He worked hard to earn the trust and even respect of the Special Counsel’s Office, submitting to 19 interviews that were “particularly valuable” because he was the first in the door, and likely inducing others to plead guilty through his cooperation. Mueller’s team recommended that he get probation, a permissible sentence under the applicable United States Sentencing Guidelines. The prosecutor recommended the same. Every defendant’s ideal sentence was his to lose.

And he lost it. He now has until March to win it back.

Flynn and his lawyers faced the same problem that has bedeviled Trump and Michael Cohen and Michael Avenatti and Paul Manafort and several other figures in this circus we call life after 2016: a muscular public relations strategy is often a terrible litigation strategy. Time and again, these players have heard their public statements quoted back at them in court to undermine their legal positions. But Flynn’s error was even more grievous – he incorporated media spin into a sentencing brief.

Flynn’s lawyers argued in his brief that the FBI wronged him: wronged him by discouraging him from having an attorney present during his interview, by failing to warn him that false statements during the interview would be a crime, and by not telling him that his answers were inconsistent with their evidence so that he could correct himself. The Flynn-as-Deep-State-victim narrative was pleasing to Trump partisans and Mueller foes, but suicidally provocative to a federal judge at sentencing.

Federal judges demand sincere acceptance of responsibility from people pleading guilty, especially when they’re cooperating with the government, and especially when they’re asking for a lenient sentence. Flynn’s sentencing arguments effectively told Sullivan that Flynn saw himself as a victim, rather than a contrite wrongdoer. Sullivan seized ominously on that issue from the start of the hearing, interrogating Flynn’s attorneys about how their argument could be consistent with acceptance of responsibility. Eventually he forced Flynn and his attorneys to concede that they were not arguing that Flynn was entrapped or that his rights were violated, and made Flynn repeat several times that he had pled guilty because he was, in fact, guilty. Flynn was surprised, but criminal defense attorneys weren’t: That’s what happens when you deflect blame at your own sentencing.

Flynn’s tactical error was compounded by unfortunate timing. On Monday, federal prosecutors in Virginia indicted two Flynn associates for violating the Foreign Agents Registration Act; and the indictment clearly demonstrated Flynn’s central role in the crime. Sullivan pounced on this fact. He implied that Flynn, by being allowed to plead to the single false statement charge, has already escaped more punishment than he should.

Sullivan’s anger was palpable. He openly expressed what he termed “disgust” for Flynn’s actions and asserted “arguably, you sold your country out.” He noted that Flynn lied both to the FBI and to members of the Trump administration. In an intemperate moment for which he later apologized, he asked if Flynn had committed treason. Flynn had not — nobody thought he had — but it’s a bad sign when your judge used the T-word at your false statements sentencing hearing. If Flynn’s lawyers had not agreed to postpone the sentencing, it’s probable Sullivan would have given him time in jail.

For a year online conspiracy theorists and marginal publications have argued that Sullivan would dismiss the case because the government failed to turn over exculpatory material, or because his interview was conducted incorrectly. Since Flynn filed his sentencing brief, more mainstream outlets – including Fox News and the Wall Street Journal’s editorial page – have taken up the cause, proclaiming that the FBI broke the law in its interview. Those arguments are, and have always been, errant nonsense, as any legal professional should know. Could it be that Flynn and his lawyers included the disastrous Flynn-as-victim pitch in their brief because they came to accept the partisan din – because they forgot that federal judges don’t react like people on Twitter? That would be a very 2018 way to go to federal prison.

Huawei in the World: In a rare and critical moment since the arrest in Canada of Huawei’s chief financial officer, whom the U.S. is accusing of violating American sanctions on Iran, an official from the Chinese telecoms giant is publicly engaging with foreign reporters. Huawei is a key player in China’s quest to become a technology powerhouse, as well as in growing economic and industrial tensions between China and the U.S., given a lack of clarity about the relationship the company may have with the Chinese government. China, of course, is playing a global influence game, including outstripping other countries in financing critical infrastructure projects across the African continent.

Flynn, Interrupted: Michael Flynn, the former prominent campaign surrogate to Donald Trump, is cooperating with multiple investigations, from the Russia probe to a third investigation of unknown nature. The sentencing judge wasn’t moved by a request for leniency, postponing a status hearing on Flynn’s cooperation until March of next year. Did Flynn’s lawyers badly miscalculate the defense strategy? Or was a pardon on their minds? Natasha Bertrand and Madeleine Carlisle look at what we now know (and what we still don’t).

Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious: Disney’s remake machine ramps up once again tomorrow evening with the opening of Mary Poppins Returns, the ambitious follow-up to the 1964 classic, which recasts Emily Blunt as the titular aerodynamic nanny. Though the film is a cheerful sequel, writes Christopher Orr, it echoes the original in ways that read either clever or lazy, depending on how large a spoonful of sugar you’re willing to take it with.

— Haley Weiss and Shan Wang

Snapshot Instagram is a feeding ground for people with wildly varying followings jostling to get paid by a brand to promote its stuff. But sponsorship deals beget more sponsorship deals, and now influencer wannabes on the platform are posting fake ads, reports Taylor Lorenz. Confusion ensues. (Image: Shutterstock)Evening Read

Instagram is a feeding ground for people with wildly varying followings jostling to get paid by a brand to promote its stuff. But sponsorship deals beget more sponsorship deals, and now influencer wannabes on the platform are posting fake ads, reports Taylor Lorenz. Confusion ensues. (Image: Shutterstock)Evening ReadPresident Trump’s school-safety commission, established following the February Parkland school shooting, released a set of recommendations Tuesday, including one to do away with a federal policy urging schools not to punish minority students at a higher rate than white students:

The commission’s recommendation to roll back the Obama administration’s school-discipline guidance does not come as a surprise. Republicans have decried the policy as government overreach since it was released in 2014. The policy advocated “constructive approaches” to school discipline, such as victim-offender mediation, as opposed to harsher penalties such as suspensions or expulsions.

The Trump administration’s discipline recommendation comes alongside several bipartisan common-sense measures in the report, including encouraging teachers, administrators, and parents to be vigilant about reporting information to the FBI; improving access to school mental-health services and counseling; and implementing best practices to curb cyberbullying. The report also advocates that districts create a “media plan” to disseminate information in the event of a shooting, alongside a suggestion to follow “No Notoriety” guidelines to keep the focus in the aftermath of an incident on the victims rather than on the shooter.

What Do You Know … About Family?1. In a discomfiting scene, the rapper Offset recently interrupted the concert of this artist—his estranged wife—asking for her forgiveness.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. Now a popular holiday gift item, these types of blankets have been used as sleep or calming aids for people in the special-needs community since at least 1999.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: Cardi B / weighted blanket

Urban DevelopmentsOur partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing city dwellers around the world. Gracie McKenzie shares their top stories:

We asked readers to grade America’s cities on two critical, unrelated metrics: tacos and transit. Now we’re sharing the results. For good Mexican food and public transportation, move here.

The tech giant Apple recently revealed a plan for nationwide job expansion and announced that Austin, Texas, will host its new 133-acre campus. Here’s the problem with that decision.

Researchers from Northeastern University have made a visualization that depicts 200 years of granular immigration data as the colorful cross section of a tree that thickens over time. “I wanted to portray the United States like an organism that’s alive and that took a long time to grow,” one says.

For more updates like these from the urban world, subscribe to CityLab’s Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

In 1989, the aspiring filmmaker Rolfe Kanefsky, who was then 19 years old, cobbled together $100,000 to make his dream movie. Thus, the first self-aware, meta-textual horror film was born. Although There's Nothing Out There was groundbreaking and garnered the attention of high-ranking studio executives, due to a series of unfortunate events, it tanked at the box office. It was dead on arrival.

Charlie Lyne, a documentary filmmaker, first saw There's Nothing Out There as a horror-obsessed teenager. “It really stuck with me,” he told The Atlantic. “Here was this oddball forerunner to [Wes Craven’s] Scream.” And yet There’s Nothing Out There preceded it by at least five years. Why wasn’t this film internationally renowned?

When Lyne looked into it, he encountered a book published by Kanefsky, in which he describes showing his screenplay to Craven’s son, who had promised to show it to his father. That’s when Lyne realized he’d stumbled upon the largely untold story of what could be a major Hollywood rip-off.

In Lyne’s short documentary Copycat, Kanefsky tells the story of his disillusionment. His voice is heard while images from his own film, Craven’s, and other Hollywood horror classics play on-screen.

“I went to interview Rolfe at his apartment in North Hollywood, and the place was like a horror-movie museum, absolutely stuffed with DVDs, books, and memorabilia,” Lyne said. “Once Rolfe started talking, I realized his conversational style was exactly the same: wall-to-wall references to obscure horror films and exploitation movies.” When it came time to edit the film, it felt natural for Lyne to adopt this patchwork, reference-heavy style. “After all, that's the way Rolfe thinks,” he said.

It’s clear from the film that despite his misfortune, Kanefsky isn’t bitter; he’s just happy that his film is now remembered as being ahead of its time. Lyne said that the filmmaker never attempted to contact the Cravens about Scream, either. “I think that’s partly because he knows how complicated and messy these things are,” said Lyne. “Was There's Nothing Out There an influence on Scream? It's possible, maybe even probable. But at the same time, they were both responding to the same set of well-worn horror tropes, so it's entirely possible they just arrived at the same idea independently.”

Besides, Lyne said, everyone has a story about an idea they had first that later went on to become successful in a different form. “I remember, in the taxi over to Rolfe’s apartment, telling the driver what I was working on,” he said, “and he proceeded to tell me that he had originally come up with the idea for the film Tooth Fairy, years before they made it into a movie with The Rock.”

Written by Olivia Paschal (@oliviacpaschal) and Elaine Godfrey (@elainejgodfrey)

Today in 5 LinesA federal judge agreed to delay former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn’s sentencing for lying to the FBI. Flynn requested the delay, signaling his fear that he might serve prison time despite his cooperation with three separate investigations.

Democrats rejected an offer from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell that would have kept the federal government open in exchange for Congress reprogramming $1 billion in unspent funds to implement Trump’s immigration policies. Funding for roughly one-quarter of the federal government runs out on Friday at midnight.

Arizona Governor Doug Ducey appointed Republican Representative Martha McSally to fill the Senate seat being vacated by Senator Jon Kyl. McSally lost the November election for Arizona’s other Senate seat to Democrat Kyrsten Sinema.

The New York Attorney General’s office said that the Trump Foundation will dissolve amid allegations that Trump and his children engaged in “persistently illegal conduct” and used the foundation for personal and political gain.

The Trump administration’s school-safety commission released long-anticipated recommendations for improving school safety, including one that would scrap a federal policy urging schools not to punish minority students at a higher rate than white students.

Today on The AtlanticDeluded: Paul Ryan’s account of his tenure as Speaker of the House is drastically disconnected from reality, argues David Frum.

Bankrolled: Big donors are shunning Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s potential presidential campaign because she urged former Senator Al Franken to resign. But Gillibrand’s got millions in the bank. (Edward-Isaac Dovere)

On Whose Authority?: A Supreme Court decision could reclassify nearly half of Oklahoma as “Indian country”—and result in new trials for nearly 2,000 Native American inmates. (Garrett Epps)

A New Purity Test: Former Texas Senate candidate Beto O’Rourke was criticized by progressives for taking money from fossil-fuel corporations, demonstrating how significant portions of the Democratic Party are starting to view corporations as the enemy, argues Peter Beinart.

Snapshot Former national security adviser Michael Flynn arrives for his sentencing hearing at U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. Jonathan Ernst / ReutersWhat We’re Reading

Former national security adviser Michael Flynn arrives for his sentencing hearing at U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. Jonathan Ernst / ReutersWhat We’re ReadingAn Epidemic in the Nation’s Capital: The rate of fatal drug overdoses has increased among black Americans twice as fast as it has among white Americans—and nobody’s talking about it. (Peter Jamison, Whitney Shefte, and André Chung, The Washington Post)

Uncle Joe’s Platform: Former Vice President Joe Biden could very well be the Democratic nominee for president. But where does he actually stand on policy? (Matthew Yglesias, Vox)

What Regulators Missed: An investigation from NPR and Frontline found that thousands of coal miners are suffering from advanced-stage black lung disease, and federal regulators failed to respond to signs of danger.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Lawyers for retired General Michael Flynn had every reason to celebrate. They managed to get their client—who lobbied against U.S. interests while serving as a top Donald Trump–campaign surrogate; tried to undermine the Barack Obama administration’s Russia policy while still a private citizen; and, as a sitting national-security adviser, worked to conceal it all from the Justice Department—a recommendation of no jail time from the government. But they appeared to have made a last-minute miscalculation that put Flynn’s potential lenient sentence in doubt.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller, who is investigating a potential conspiracy between the Trump campaign and Russia, appeared to let Flynn off the hook for his crimes in exchange for his cooperation in the Russia probe and an investigation into illegal lobbying for the Turkish government that is being conducted out of the Eastern District of Virginia. Flynn is also cooperating in a third investigation, the nature of which remains unknown. Indeed, before Tuesday’s hearing, it had appeared all but certain that Flynn’s decision to assist the government early and fully would spare him jail time. But that leniency apparently wasn’t enough for Flynn’s lawyers.

[Read: A surge in foreign-influence prosecutions]

In a sentencing memo filed last week, Flynn’s lawyers, Robert Kelner and Stephen Anthony, indicated that the FBI agents who interviewed the former national-security adviser in January 2017 about his conversations with the former Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak had entrapped him, lulled him into a false sense of security, and failed to insist that he have a lawyer present for the interview.

Judge Emmet Sullivan, however, who was set to issue Flynn’s sentence on Monday, was not sympathetic. “How is raising these points consistent with accepting responsibility?” he asked Flynn and his lawyers as they stood before him at the lectern on Tuesday. He then lambasted Flynn for lying to federal agents on White House grounds while serving as the president’s top national-security adviser in January 2017, and for lying about his lobbying work for the Turkish government. “Arguably, you sold out your country,” Sullivan said. He added that while he would take Flynn’s 33-year public-service career and cooperation into account when sentencing him, he would not try to hide his “disdain” and “disgust” for Flynn’s crimes, and asked the government at one point whether Flynn’s conduct rose to the level of treason.

Flynn’s lies to the FBI were brazen, according to a summary of the agents’ interview with him last January that was released on Monday night. The summary, known as a 302, reveals that Flynn falsely stated that he did not recall discussing with Kislyak the Obama administration’s new sanctions, expulsion of diplomats, and shuttering of Russian compounds in response to Moscow’s election interference. Flynn also falsely claimed that he did not learn about the Obama administration’s actions against Russia until later, because he was vacationing in the Dominican Republic on December 28 when the executive order was signed.

What he did not tell the agents, however, was that when he and Kislyak spoke on December 29, it was after Flynn had already discussed how to respond to the new sanctions with his deputy, K. T. McFarland, who was at Mar-a-Lago with Trump at the time. The transition team determined that the sanctions could have a negative effect on the incoming Trump administration’s foreign-policy goals, so Flynn asked Kislyak to refrain from escalating the situation until Trump took office. Flynn also failed to tell the FBI that Kislyak called again on December 31 to inform him that Russia had decided not to retaliate at Flynn’s request.

Additionally, Flynn falsely stated that he had called Russia, along with other countries, on December 22, 2016, only as part of a drill “to see who the administration could reach in a crisis” and to “get a sense” of where they stood on an impending United Nations vote on Israeli settlements, rather than to swing those votes. He did not tell the FBI, moreover, that Kislyak called Flynn on December 23 and told him that Russia would indeed vote the way the U.S. wanted them to.

[Read: Michael Flynn is worse than a liar]

Sullivan’s disdain stood in stark contrast to the government’s characterization of Flynn in its sentencing memo as a star witness who had provided “substantial” assistance to at least three ongoing investigations. Prosecutor Brandon Van Grack said in court on Tuesday that the government believed Flynn had fully accepted responsibility for his conduct. But the implication by Flynn’s lawyers that Flynn had been entrapped by the bureau hung in Sullivan’s mind.

“I don’t know what his lawyers were thinking,” says Nick Akerman, a former assistant U.S. attorney, a former assistant special Watergate prosecutor, and a partner at Dorsey & Whitney. As a defense lawyer, “you really ought to be in the position of complete contrition and saying, ‘Look, my client did something that was wrong, he made up for it, he’s cooperated,’” he says. “To take the tack that somehow the government was at fault here is completely absurd.” There is “no question whatsoever” that Flynn’s lawyers miscalculated, says the former federal prosecutor Renato Mariotti. “The judge rightly saw that there was no misconduct by the government and appropriately criticized Flynn’s apparent failure to accept responsibility for his criminal activity,” he adds.

Mimi Rocah, a former federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York, agrees that Flynn’s lawyers had clearly made a “very misguided appeal” to Sullivan. But she notes that it may also have been a play for a pardon from President Trump. “Maybe on some level, this was an appeal to Trump and his base,” Rocah says. Mark Zaid, a national-security attorney in Washington, D.C., says that if the defense’s strategy was to send a message to the president, only “time will tell” whether that strategy was sound. “But that’s more a long-term political strategy, and I would imagine in the short term Flynn is far more interested in knowing whether or not he can avoid jail,” he says.

Kelner, Flynn’s lawyer, asked that the judge not hold the sentencing memo against their client. “General Flynn recognizes the obligations that came with higher office, and that this is a serious offense,” he said. “We don’t mean to dispute that.” The president has not tried to hide his continued support for Flynn, and has lamented that Flynn was treated unfairly by the FBI. “Good luck today in court to General Michael Flynn,” Trump tweeted on Tuesday. White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders said on Tuesday that Flynn had been “manipulated” by the bureau. Mueller’s office shot back at any claim of wrongdoing by the FBI in a response to Flynn’s lawyers released last week. “A sitting National Security Advisor, former head of an intelligence agency, retired Lieutenant General, and 33 year veteran of the armed forces knows he should not lie to federal agents,” they wrote.

Sullivan’s harsh words nearly an hour into his sentencing hearing seemed to unnerve Flynn, who had appeared confident up until that point in his decision to proceed with sentencing before all his cooperation with the government was over. “Yes,” he responded loudly, when the judge asked for the third time whether he would like to meet with his lawyers to reconsider moving forward. Ultimately, Sullivan postponed a status hearing on Flynn’s cooperation until March 13.

Flynn is still cooperating with prosecutors in the Eastern District of Virginia in an investigation into Turkish lobbying, according to Kelner, and will “likely” have to testify in that case. Flynn’s former associates Bijan Kian and Ekim Alptekin were indicted in the Eastern District on Monday as part of a conspiracy they allegedly concocted with Flynn in 2016 to “covertly and unlawfully” influence U.S. public opinion as it relates to the exiled Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen.

Sullivan said that while he can’t guarantee that Flynn will receive a lighter sentence after his cooperation is fully over, it would at least allow the court to take everything into consideration with regard to Flynn’s assistance to prosecutors. “I can’t consider the full extent of your cooperation in this case,” Sullivan said, noting that Flynn’s crime of lying about his conversations with the Kislyak was “very serious” and resulted in top White House officials—including the vice president and press secretary—lying to the public. “You can’t minimize that,” he said. “If you want to postpone this, that’s fine with me.”

Flynn’s downfall from revered three-star general to convicted felon was rapid, beginning after President Barack Obama fired him as head of the Defense Intelligence Agency in 2014 following a chaotic, “disruptive” tenure, and accelerating with Trump’s political rise. In his January 2017 interview with the FBI, a redacted summary of which was made available by the special counsel’s office on Monday night, Flynn acknowledged that he had been friendly with his Russian counterpart, former GRU Director Igor Sergun, when he was head of the DIA. But by the end of 2015, Flynn was sitting next to Russian President Vladimir Putin at an awards dinner for the state-sponsored Russian news agency RT. By December 2016, he was working with both Turkish officials for cash and Russian officials for political capital. And by February 2017, he was ousted from the White House and under FBI investigation.

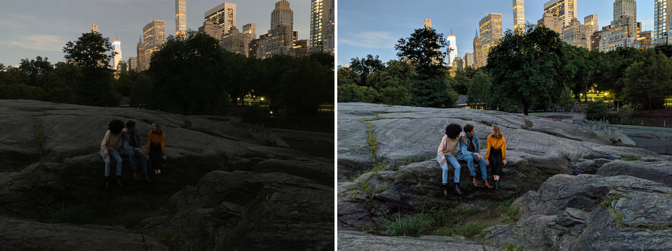

When a prominent YouTuber named Lewis Hilsenteger (aka “Unbox Therapy”) was testing out this fall’s new iPhone model, the XS, he noticed something: His skin was extra smooth in the device’s front-facing selfie cam, especially compared with older iPhone models. Hilsenteger compared it to a kind of digital makeup. “I do not look like that,” he said in a video demonstrating the phenomenon. “That’s weird … I look like I’m wearing foundation.”

He’s not the only one who has noticed the effect, either, though Apple has not acknowledged that it’s doing anything different than it has before. Speaking as a longtime iPhone user and amateur photographer, I find it undeniable that Portrait mode—a marquee technology in the latest edition of the most popular phones in the world—has gotten glowed up. Over weeks of taking photos with the device, I realized that the camera had crossed a threshold between photograph and fauxtograph. I wasn’t so much “taking pictures” as the phone was synthesizing them.

This isn’t a totally new phenomenon: Every digital camera uses algorithms to transform the different wavelengths of light that hit its sensor into an actual image. People have always sought out good light. In the smartphone era, apps from Snapchat to FaceApp to Beauty Plus have offered to upgrade your face. Other phones have a flaw-eliminating “beauty mode” you can turn on or off, too. What makes the iPhone XS’s skin-smoothing remarkable is that it is simply the default for the camera. Snap a selfie, and that’s what you get.

FaceApp adding substantially more George Clooney to my face than actually exists (Alexis Madrigal / FaceApp)

FaceApp adding substantially more George Clooney to my face than actually exists (Alexis Madrigal / FaceApp)These images are not fake, exactly. But they are also not pictures as they were understood in the days before you took photographs with a computer.

What’s changed is this: The cameras know too much. All cameras capture information about the world—in the past, it was recorded by chemicals interacting with photons, and by definition, a photograph was one exposure, short or long, of a sensor to light. Now, under the hood, phone cameras pull information from multiple image inputs into one picture output, along with drawing on neural networks trained to understand the scenes they’re being pointed at. Using this other information as well as an individual exposure, the computer synthesizes the final image, ever more automatically and invisibly.

The stakes can be high: Artificial intelligence makes it easy to synthesize videos into new, fictitious ones often called “deepfakes.” “We’ll shortly live in a world where our eyes routinely deceive us,” wrote my colleague Franklin Foer. “Put differently, we’re not so far from the collapse of reality.” Deepfakes are one way of melting reality; another is changing the simple phone photograph from a decent approximation of the reality we see with our eyes to something much different. It is ubiquitous and low temperature, but no less effective. And probably a lot more important to the future of technology companies.

In How to See the World, the media scholar Nicholas Mirzoeff calls photography “a way to see the world enabled by machines.” We’re talking about not only the use of machines, but the “network society” in which they produce images. And to Mirzoeff, there is no better example of the “new networked, urban global youth culture” than the selfie.

The phone manufacturers and app makers seem to agree that selfies drive their business ecosystems. They’ve dedicated enormous resources to taking pictures of faces. Apple has literally created new silicon chips to be able to, as the company promises, consider your face “even before you shoot.” First, there’s facial detection. Then, the phone fixes on the face’s “landmarks” to know where the eyes and mouth and other features are. Finally, the face and rest of the foreground are depth mapped, so that a face can pop out from the background. All these data are available to app developers, which is one reason for the proliferation of apps to manipulate the face, such as Mug Life, which takes single photos and turns them into quasi-realistic fake videos on command.

Nothing creepy about this Mug Life image at all (Alexis Madrigal / Mug Life)

Nothing creepy about this Mug Life image at all (Alexis Madrigal / Mug Life)All this work, which was incredibly difficult a decade ago, and possible only on cloud servers very recently, now runs right on the phone, as Apple has described. The company trained one machine-learning model to find faces in an enormous number of pieces of images. The model was too big, though, so they trained a smaller version on the outputs of the first. That trick made running it on a phone possible. Every photo every iPhone takes is thanks, in some small part, to these millions of images, filtered twice through an enormous machine-learning system.

But it’s not just that the camera knows there’s a face and where the eyes are. Cameras also now capture multiple images in the moment to synthesize new ones. Night Sight, a new feature for the Google Pixel, is the best-explained example of how this works. Google developed new techniques for combining multiple inferior (noisy, dark) images into one superior (cleaner, brighter) image. Any photo is really a blend of a bunch of photos captured around the central exposure. But then, as with Apple, Google deploys machine-learning algorithms over the top of these images. The one the company has described publicly helps with white balancing—which helps deliver realistic color in a picture—in low light. It also told the Verge that “its machine learning detects what objects are in the frame, and the camera is smart enough to know what color they are supposed to have.” Consider how different that is from a normal photograph. Google’s camera is not capturing what is, but what, statistically, is likely.

Google shows off its Night Sight performance (right), relative to the iPhone XS on the left (Google).

Google shows off its Night Sight performance (right), relative to the iPhone XS on the left (Google).Picture-taking has become ever more automatic. It’s like commercial pilots flying planes: They are in manual control for only a tiny percentage of a given trip. Our phone-computer-cameras seamlessly, invisibly blur the distinctions between things a camera can do and things a computer can do. There are continuities with pre-existing techniques, of course, but only if you plot the progress of digital photography on some kind of logarithmic scale.

High-dynamic range, or HDR, photography became popular in the 2000s, dominating the early photo-sharing site Flickr. Photographers captured multiple (usually three) images of the same scene at different exposures. Then, they stacked the images on top of one another and took the information about the shadows from the brightest photo and the information about the highlights from the darkest photo. Put them all together, and they could generate beautiful surreality. In the right hands, an HDR photo could create a scene that is much more like what our eyes see than what most cameras normally produce.

A good example of the intense surreality of some HDR photos (Jimmy McIntyre / Flickr)

A good example of the intense surreality of some HDR photos (Jimmy McIntyre / Flickr)Our eyes, especially under conditions of variable brightness, can compensate dynamically. Try taking a picture of the moon, for example. The moon itself is very bright, and if you try to take a photo of it, you have to expose it as if it were high noon. But the night is dark, obviously, and so to get a picture of the moon with detail, the rest of the scene is essentially black. Our eyes can see both the moon and the earthly landscape with no problem.

Google and Apple both want to make the HDR process as automatic as our eyes’ adjustments. They’ve incorporated HDR into their default cameras, drawing from a burst of images (Google uses up to 15). HDR has become simply how pictures are taken for most people. As with the skin-smoothing, it no longer really matters if that’s what our eyes would see. Some new products’ goal is to surpass our own bodies’ impressive visual abilities. “The goal of Night Sight is to make photographs of scenes so dark that you can’t see them clearly with your own eyes — almost like a super-power!” Google writes.

Since the 19th century, cameras have been able to capture images at different speeds, wavelengths, and magnifications, which reveal previously hidden worlds. What’s fascinating about the current changes in phone photography is that they are as much about revealing what we want to look like as they are investigations of the world. It’s as if we’ve discovered a probe for finding and sharing versions of our faces—or even ourselves—and it’s this process that now drives the behavior of the most innovative, most profitable companies in the world.

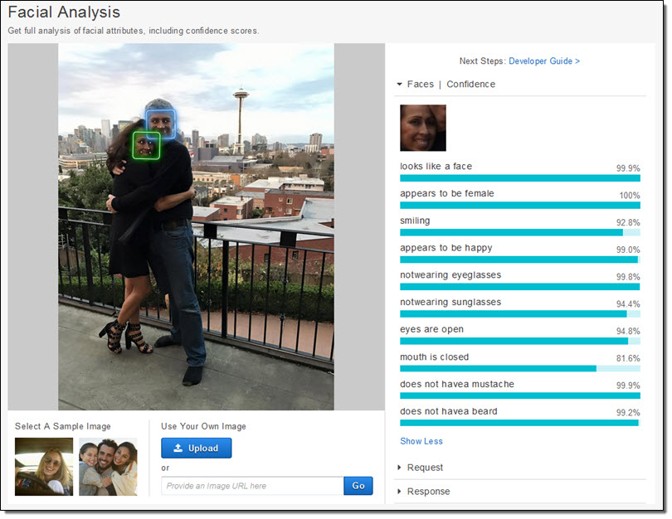

Amazon demonstrates the capabilities of its facial-recognition technology (Amazon).

Amazon demonstrates the capabilities of its facial-recognition technology (Amazon).Meanwhile, companies and governments can do something else with your face: create facial-recognition technologies that turn any camera into a surveillance machine. Google has pledged not to sell a “general-purpose facial recognition” product until the ethical issues with the technology have been resolved, but Amazon Rekognition is available now, as is Microsoft’s Face API, to say nothing of Chinese internet companies’ even more extensive efforts.

The global economy is wired up to your face. And it is willing to move heaven and Earth to let you see what you want to see.

Not necessarily the top photos of the year, nor the most heart-wrenching or emotional images, but a collection of photographs that are just so 2018. From Gritty the Philadelphia Flyers mascot to Fortnite tournaments, from the airplane taken for a tragic joyride at SeaTac Airport to a caravan of thousands journeying through Mexico to the United States, from Mandarin Duck to Knickers the steer, and much more. This is 2018.

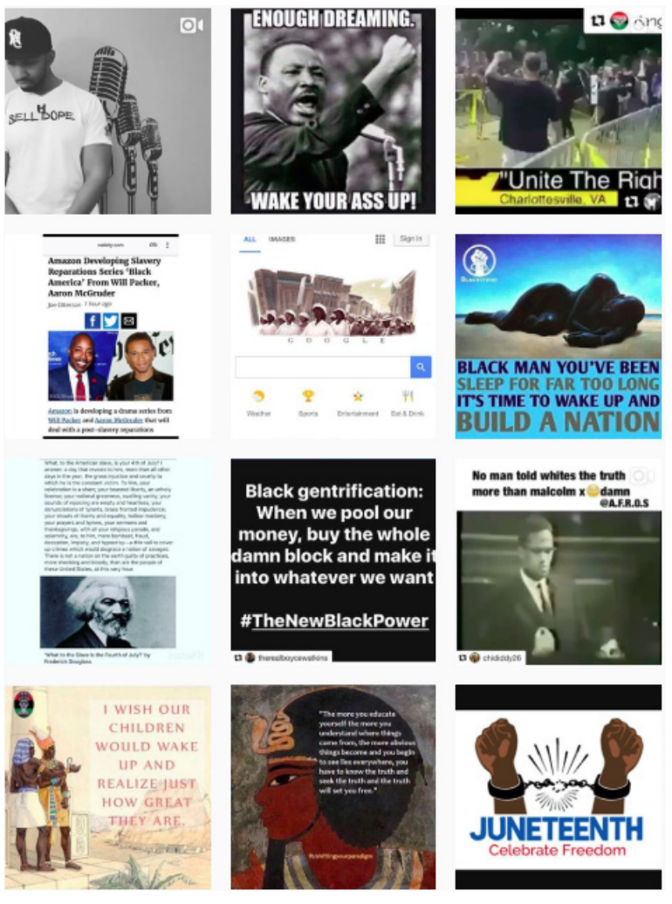

In their efforts to influence the 2016 election, Russian operatives targeted every major social platform, but one demographic group, black Americans, got special treatment, according to two reports made public by the Senate Intelligence Committee yesterday.

The reports—one published by New Knowledge, a new disinformation-monitoring group, and the other by the Computational Propaganda Project at the University of Oxford—both tally large numbers of posts across social media that generated millions of interactions with unsuspecting Americans. New Knowledge counted up 77 million engagements on Facebook, 187 million on Instagram, and 73 million on Twitter. The think tank divvied up the activity into three buckets: content that targeted the left, the right, and … African Americans.

[Read: What Facebook did to American democracy]

Partially in response to the reports, the NAACP has called for a one-day boycott of Facebook and Instagram. The NAACP president, Derrick Johnson, hit the company for allowing “the utilization of Facebook for propaganda promoting disingenuous portrayals of the African American community.”

The way politicians and journalists usually describe these Russian posts is to say that they sought to “heighten tensions between groups already wary of one another” or “exploit racial divides” by “exploiting existing political and racial divisions in American society.”

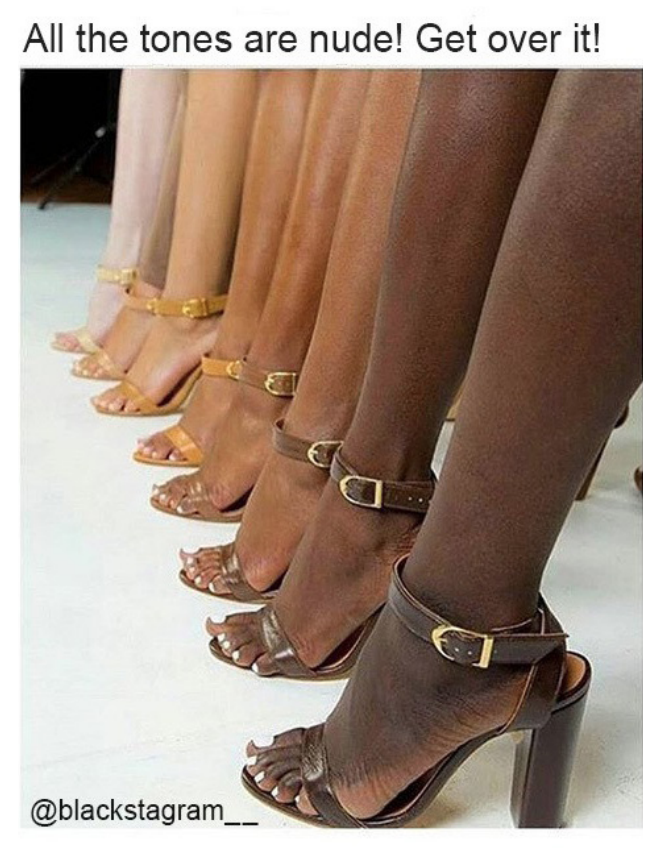

While right-leaning political posts were often explicitly racist, and both types of political posts surely tried to stoke polarization, the posts that targeted black people were different. They promoted a generally Afrocentric worldview, celebrated the freedom of black people, and called for equality. Take the following image post, which New Knowledge said generated the most likes of any Instagram post in its data set. While it was posted by a Russian-linked account, it was originally created by a black-owned leather-goods company, Kahmune.

(New Knowledge’s The Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency)

(New Knowledge’s The Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency)Is this really “exploiting” racial divides or “heightening tensions”? At most, this post points out something obvious about the nature of American popular culture (calling a certain shade of beige “nude” is dumb) that makes white people mildly uncomfortable.

In another case, an IRA-controlled Facebook page reposted video footage of police brutality, garnering more than half a million shares. If that heightens racial tensions in America, it seems hard to blame the Russians for that.

The IRA operatives were able to deeply interpenetrate real black media. They became part of the meme soup of online black life, sharing and being reshared by real people, as seen below. These posts, then, created the audience that they targeted with posts arguing “that Mrs. Clinton was hostile to African American interests, or that black voters should boycott the election,” as The New York Times put it.

(New Knowledge’s The Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency)

(New Knowledge’s The Tactics and Tropes of the Internet Research Agency)These posts targeting black people provide the most intense examples of the problem that Facebook faces from foreign actors. Facebook has taken down these posts, but explicitly not because of their content. Instead, the company backed into a way of targeting behavior by foreign actors. According to Facebook, these posts are bad only because they are inauthentic.

Facebook has long promoted the idea that users and posts on the service should be “authentic.” “Representing yourself with your authentic identity online encourages you to behave with the same norms that foster trust and respect in your daily life offline,” the company wrote in a letter to shareholders ahead of its IPO in February 2012. “Authentic identity is core to the Facebook experience, and we believe that it is central to the future of the web.”

[Read: The secretive organization quietly spending millions on Facebook political ads]

For several years, the company emphasized the need to maintain “authentic relationships,” but primarily in the context of people and companies buying “fake likes” for their pages. Authenticity was a business principle, not a political one. “Businesses won’t achieve results and could end up doing less business on Facebook if the people they’re connected to aren’t real,” the company explained in 2014. “It’s in our best interest to make sure that interactions are authentic.”

When the Russian influence operation began to be excavated in the wake of the 2016 election, Facebook began to use the phrase “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” Facebook cleverly adapted a policy that was designed to fight spam to fight the activities of foreign actors. It’s an understandable policy shift meant to connect the specific fight around electoral interference to this core Facebook value of “authenticity.”

At the same time, the entire enterprise of “influencer” marketing sure seems like coordinated inauthentic behavior. But financial motivations are automatically deemed authentic and legitimate. Teams of people are recruited from across the world to promote products and ideas that may be dubious.

Also, there are plenty of businesses that use racial-solidarity themes to sell products. Many others drive much more directly at polarizing issues—like gun control—to do the same. One large political-action group spawned a flock of disguised pages to promote candidates and issues, yet they were also seen by Facebook as playing by the rules.

If the Russians had simply been regular businesses with products to sell or a media empire to build, what they did, in the vast majority of cases, would have been fine. Even American political actors working on behalf of global oil companies to, say, thwart climate-change action would be deemed authentic.