Facing Facebook: For years, Facebook has been sharing user data, including private messages, with other large technology platforms including Netflix, Spotify, and Microsoft’s Bing search engine, according to a New York Times report. Few of these data-sharing partnerships have even proven useful for Facebook, writes Alexis Madrigal, and the revelations are, most of all, a testament to Facebook’s sloppy attitude toward user data and privacy over the years. Here’s a refresher on Facebook’s impact on the informational underpinnings of American democracy.

Military Retreat: The White House—including President Donald Trump, via Twitter—confirmed Wednesday that plans to withdraw the U.S. military presence in Syria are under way, though details about the timeline or actual process for the troops’ removal is unclear. Though troops were initially deployed to combat ISIS’s stronghold on the country, their removal could bring immeasurable chaos and unnerve other American allies.

Border Crisis: Hardline views over immigration and borders in France have come to the fore yet again in the recent trial of seven pro-immigration activists who’d assisted at a critical entry point in the French Alps, between Italy and France. The “Briançon Seven,” as the activists would come to be called, were charged with violating a ban on helping foreigners enter the country illegally. Karina Piser writes on what the case means for the tightening borders of Europe.

—Haley Weiss and Shan Wang

Snapshot Caribou, the undomesticated cousin species to reindeer, are going extinct. Hillary Rosner brings us the story of what’s leading to the disappearance of these herds, and the monumental effort First Nations communities in Canada are leading to save them. (Illustration by Cornelia Li)Evening Read

Caribou, the undomesticated cousin species to reindeer, are going extinct. Hillary Rosner brings us the story of what’s leading to the disappearance of these herds, and the monumental effort First Nations communities in Canada are leading to save them. (Illustration by Cornelia Li)Evening ReadWill Stancil explains what a scandal surrounding an elite private school’s college-application fraud implicitly reveals about our expectations of the elite higher-education system:

T. M. Landry shows how hungry our society is for what might be deemed “miracle students.” The Landrys are not the only ones to take advantage of this hunger, although their alleged fraud appears to have been especially egregious. Many other schools implicitly offer the same miracle: students who have endured great hardship and succeeded beyond all expectations. An entire genre of charter schools, often called “no excuses” schools, have adopted a similar rhetorical tack. These schools, explicitly targeted at poor students of color, claim to fuse rigid discipline and intense expectations to achieve an academic transformation. Their advocates often imply that only such a crucible can produce poor and nonwhite college-ready students. Like T. M. Landry, these schools have attracted disproportionate attention from colleges, not to mention media and politicians.

What Do You Know … About Science, Technology, and Health?1. President Trump announced on Saturday that this cabinet member will be the next to depart the White House, leaving the Interior Department in the hands of the former oil lobbyist David Bernhardt.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. This civil-rights group has called for a boycott of Facebook and Instagram after the release of two reports showing that Russian operatives specifically targeted African American voters on social media before the 2016 election.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. Efforts are under way in Canada to protect the last remaining North American groups of this four-legged animal.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: ryan zinke / The NAACP / Caribou

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Another year in American politics is coming to a close, and what a year it’s been! We saw congressional investigations, turmoil in the administration, debates over consequential policy issues such as immigration and health care, and midterm elections with record-high turnout. For the rest of the week, instead of our usual newsletter format, we’ll be sharing a selection of some of The Atlantic’s best politics stories from 2018.

We’re sharing pieces that touch on some of the key figures and themes that have animated American politics throughout the past 12 months—from an essay about the nuance lacking in the national debate over gun control to an examination of how our political discourse has spun out of control. As always, thanks for reading, and we’ll be back tomorrow and Friday with more to read from the past year.

-Elaine Godfrey and Maddie Carlisle

Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at the Kennedy School's Institute of Politics at Harvard University (Charles Krupa / AP)

Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at the Kennedy School's Institute of Politics at Harvard University (Charles Krupa / AP)How Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Plans to Wield Her Power

Russell Berman

“But, I don't want to be obnoxious either,” Ocasio-Cortez insisted. “Let's just get things done. I'll be really quiet if we get things done. If we pass Medicare for All, I'm going to be silent as a lamb.” → Read on.

How the House Intelligence Committee Broke

Natasha Bertrand

“The panel would be “nonpartisan,” he promised. “There will be nothing partisan about its deliberations.” Four decades later, that promise has proven illusory. The committee’s investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election so divided the panel’s Republicans and Democrats that the chairman considered building a physical wall between staffers.”→ Read on.

The Bullet in My Arm

Elaina Plott

“I stroked my mother’s hair as she cried and drove me to the hospital. The surgeon said the bullet was small, maybe a .22-caliber, and too deep in the muscle to take out, so it’s still in my arm. They never caught the shooter, or came up with a motive.”→ Read on.

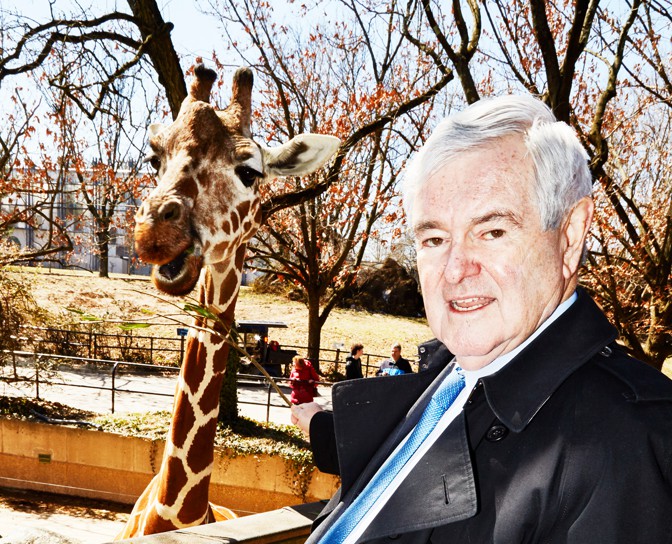

Newt Gingrich at the Philadelphia Zoo (Amy Lombard)

Newt Gingrich at the Philadelphia Zoo (Amy Lombard)How Newt Gingrich Destroyed American Politics

McKay Coppins

“Newt Gingrich is an important man, a man of refined tastes, accustomed to a certain lifestyle, and so when he visits the zoo, he does not merely stand with all the other patrons to look at the tortoises—he goes inside the tank.”→ Read on.

Stacey Abrams's Plan for Georgia's Health-Care Crisis

Vann R. Newkirk II

“Across the country, black women’s health—particularly the fate of mothers and their newborns—is in peril, and mortality rates have spiked. Nowhere is this truer than in Georgia.”→ Read on.

Trump's Gang of Crooks and Liars

David A. Graham

“Collusion with Russia may or may not turn out to be a real scandal, depending on what Mueller finds, but it is not the only scandal...The scale of dishonesty and criminality that is now apparent is an enormous scandal in its own right.”→ Read on.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

The New York Times has once again gotten its hands on a cache of documents from inside Facebook, this time detailing data-sharing arrangements between the company and other corporations, which had “more intrusive access to users’ personal data than [Facebook] has disclosed” for most of the past decade, the article revealed.

Microsoft’s search engine, Bing, got Facebook users’ friends, whether or not the users agreed to grant that access. Netflix and Spotify got access to users’ messages. Amazon got names and contact information. And, of course, Facebook got things in return. The Times states that Facebook used data from other companies, including Amazon, in its “People You May Know” feature, which has long attracted attention for its mysterious suggestions.

But while the story recalls the explosive Cambridge Analytica episode, it’s much more mundane. These were not bad actors, but merely actors playing exactly the role that Facebook wanted them to play. The goals of these integrations were not nefarious, at least from what we currently know, even if the idea that Spotify’s engineers would have access to your Facebook message data is probably not intuitive to most people.

[Read: Cambridge Analytica and the dangers of Facebook data harvesting]

Facebook responded to the story with a long blog post, where the company argued that the data sharing “work was about helping people” to do things on the internet “like seeing recommendations from their Facebook friends—on other popular apps and websites, like Netflix, The New York Times, Pandora, and Spotify.”

Which, sure: That was one thing that these data-sharing partnerships allowed. But it also allowed Facebook to grow, and grow, and grow. To entrench itself everywhere in the social-media ecosystem. Facebook was happy to trade user data to expand its business operations, and to pretend that this was all about users defies reality. Users got a small “improvement” that they didn’t ask for. Facebook got permits to build the pipes underlying its data empire.

Back when the data-sharing partnerships began in 2010, the vision Facebook had of itself could be called Everything-But-With-Facebook. The service would be the social spine for all other services on the web. You’d log in with it, share through it, integrate your Facebook friends into all online experiences. This vision had an arc that began with integrating Facebook with also-ran phone makers and ended in the failure of the concept, overall. But in between, as The Verge’s Casey Newton points out, it gave away more and more data until it overreached with what it called “instant personalization,” which customized results in Bing with Facebook data.

The company has been pulling back on this kind of arrangement for years now. It admits in the Times story, however, that the change was not primarily because of privacy concerns. Most of the deals that Facebook cut simply didn’t work for either party, despite the data transport going back and forth. As Android and iOS took over from the wider world of mobile phones and computers, Facebook’s vision of what it should be evolved. It would no longer be the social spine, but the suite of apps you cannot escape. For years, now, the model has been: everything inside Facebook. Apps that threatened that hegemony were purchased (WhatsApp, Instagram), or battled tooth and nail (Twitter, Snapchat).

[Read: Another day, another Facebook problem]

What’s fascinating is that, as with Cambridge Analytica, we’re mostly talking about the sins of Facebook past, remnants of a different idea of how the internet was going to work. Except that the Times reporting indicates that data access for many companies continued long after it should nominally have been cut off. Other companies purported to be surprised that they had the depth of access that they did. The sloppiness—basically up to the present day—remains the most incomprehensible part. For a company that is user data, Facebook sure has made a lot of mistakes spreading it around.

By the looks of it, other tech players have been been happy to let Facebook get beat up while their practices went unexamined. And then, in this one story, the radioactivity of Facebook’s data hoard spread basically across the industry. There is a data-industrial complex, and this is what it looked like.

When the nurse slipped the IV needle into his arm, Matt Sharp was calm. Yes, he knew the risks: As one of the first humans ever to receive the experimental treatment, he could end up with mutant cells running amok in his body. But he was too enamored of the experiment’s purpose to worry about that. For two decades, Sharp had been living with HIV. He’d watched the height of the AIDS crisis claim dozens of his friends’ and lovers’ lives. Now, he believed he was taking a step toward a cure.

A few months earlier, researchers had drawn white blood cells from Sharp’s body and manipulated his DNA with tiny molecules, deleting a single gene in each cell. He was about to receive an infusion that would reintroduce the tweaked cells back into his bloodstream. The procedure aimed to change the genetic makeup of these cells to make Sharp’s body resistant to HIV. Gene therapies like this had been tried before for other diseases, but experiments were put on hold when a young man died in 1999. Sharp’s body would allow researchers to test the safety of new molecular tools called “zinc fingers.”

The infusion took place in June 2010 at Quest Clinical Research, a nondescript gray building near The Fillmore in San Francisco. Sharp’s cells arrived frozen in a liquid-nitrogen-filled shipping container that looked like R2-D2 from Star Wars. After thawing them in a hot-water bath, his nurse plugged the bag into his IV line. Cloudy yellow fluid slowly drained into Sharp’s arm. Within 30 minutes, he headed back to work with billions of genetically modified cells reproducing in his arteries and veins.

[Read: Chinese scientists are outraged by reports of gene-edited babies]

Over the past decade, HIV patients like Sharp have played a major role in pushing forward the vanguard science of gene editing. The community’s close-knit advocacy networks, paired with the fact that there are clearly identifiable genes that make humans vulnerable to HIV, have made people living with the virus ready candidates for innovative—though sometimes risky—experiments. A gene-editing procedure related to HIV rocked the fields of science and medicine last month, when the Chinese researcher He Jiankui made the explosive claim that he had manipulated the genomes of twin babies who do not carry the virus in an attempt to make them resistant to it, a covert and reckless move that was widely condemned by the scientific establishment. But adult HIV patients have voluntarily participated in scientifically condoned experiments that have paved the way for further gene-editing work on, for instance, cancer and blindness.

Sharp’s journey since he signed up for his pioneering infusion illustrates the potential that DNA editing has in expanding the possibilities of being human—and also the limits of genetic medicine as a miracle cure.

Sharp, who’s now 62, has been campaigning for innovative experimental medicine since the 1980s. As a veteran of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, he says he was arrested at least eight or nine times—he can’t remember exactly—during protests against slow progress in AIDS treatment and research. He first encountered the founder of Quest Clinical Research, Jay Lalezari, in San Francisco back in the early 1990s, when the young doctor was making a name for himself with daring experiments with potentially toxic drugs. Lalezari’s research offered early hope for surviving HIV, but he initially had an uneasy relationship with activists: ACT UP staged a “die in” at one of his talks at an AIDS conference.

Over time, the activists began to trust Lalezari. Hundreds of people now credit him for saving their lives. In 2008, Lalezari was involved in an earlier gene-therapy study, funded by Johnson & Johnson, that reported unspectacular results. So when a small biotech company, Sangamo Therapeutics, approached him with a gene-editing experiment involving the new zinc-finger technology, he was skeptical that it would be a “cure.” But after careful consideration, he decided to launch an experiment and enroll 65 patients with HIV.

When Sharp learned about the gene-editing trial, he jumped at the chance to participate and agreed to be patient No. 2 in the safety study. To everyone’s relief, Sharp experienced only one side effect after the initial infusion: An intense smell lingered around his body. When he returned to Quest the next day for a checkup, his nurse could smell him coming down the hall. Paperwork from Sangamo had said to expect a garlic odor from a chemical agent that would fade after a few days, but the nurses agreed that Sharp and his fellow gene-editing patients smelled more like rancid creamed corn.

When the earliest results came back, Sharp saw dramatic improvements in his medical charts. For the first time since he was diagnosed with HIV, his T-cell count—a key marker of immune-system function—jumped up to normal, healthy levels. Sharp wanted to be in the audience when the full data were unveiled at a leading HIV conference, so he flew to Boston in February 2011. He didn’t know if his cell counts were an idiosyncratic fluke. When Lalezari presented a slide showing a significant increase in the other patients’ T-cell numbers as well, Sharp says the audience gasped.

Over the next couple of years, follow-up procedures were more uncomfortable for Sharp than the initial infusion. During rectal biopsies, he watched a video screen that showed where “the scope was going into my butt, where the clippers were going, and exactly where they were taking the snips,” he says. He was under local anesthesia and didn’t feel any pain, so he decided to narrate the procedure with an omniscient booming voice-over: “Journey to the Center of the Earth.”

No serious problems were identified among the patients in the study in rectal exams, blood samples, and general checkups. But Sharp’s lack of complications was unusual. Other patients did have notable side effects, including fever, chills, headaches, and muscle pain. According to one study, these symptoms were likely a reaction to billions of cells being reinfused into the body, rather than from the genetic modifications. Still, there are other concerns. The study’s three-year monitoring period might not have been enough to detect long-term health problems, such as cancer, caused by genetic damage from the experiment.

More pointedly, the experiment did not deliver the dream of a complete cure. Some patients experienced no lasting benefits. Sharp found long-term improvements to his immune-system health. He thinks participation in the study was worth it, but he still takes daily pills to keep the virus under control. Other patients claim that they were “cured” and stopped taking standard medicine when their bodies did, in fact, become able to control HIV.

Lalezari insists that it is irresponsible to bandy about the word cure when interpreting results from this initial research. The study was promising, but preliminary; the “primary outcome was safety,” researchers say. Current HIV medications have few risks, can reduce the virus to undetectable levels, and are becoming more affordable. Lalezari points to other HIV experimental treatments—involving antibodies, pharmaceutical drugs, and small molecules—that seem even more promising than gene editing.

The most important next step for Lalezari after his 2011 presentation in Boston was more research. If his studies could, in fact, produce a one-time treatment, as some of his patients claimed, gene-editing truly would be a game changer. But his work abruptly stalled out when it ran into a fickle reality of cutting-edge experimental work: funding troubles. Sangamo Therapeutics, the biotechnology firm that bankrolled the initial study, decided to sideline its HIV research, and instead develop treatments for other diseases with its proprietary gene-editing technology.

This enraged HIV-positive activists. “The company put it back on the shelf because they couldn’t figure out how they were going to make enough money,” says Mark Harrington, the executive director of the Treatment Action Group in New York City. Sharp, dismayed by the setback, signed an open letter to Sangamo, calling for new research initiatives. “They simply refused to follow up the initial experiment with funding for further studies,” he says.

[Read: China is genetically engineering monkeys with brain disorders]

The reasons the funding dried up are disputed. In 2013, Sangamo had become flush with cash when it signed a $320 million deal. But then its shares plummeted as an insider-trading scandal threw the company into disarray. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged Sangamo’s then–vice president of clinical research, Winson Tang, with allegedly participating in a scheme that netted more than $1.5 million in “illegal profits.”

“When Winson Tang was carted off to jail, Sangamo completely dropped the ball,” contends Lalezari, who says he maintains contact with the biotech firm to leave open the door to future experiments. “If you want to do research with industry, you can never forget that you are dancing with the devil.”

Sandy Macrae, the president and CEO of Sangamo, disputes such an inference, claiming that the decision to move away from HIV came before the Winson Tang insider-trading scandal. But the company acknowledges that it didn’t see HIV as the most valuable investment. Macrae took charge of Sangamo last year, shortly after the company’s stocks bottomed out at around $3 a share, and he has been working to turn things around. The company’s headquarters sits next to a boat-parts store in Richmond, California, a city at the edge of the Bay Area that is also home to a train yard, a Chevron oil refinery, a yacht club, and Rosie the Riveter National Park.

“I had to make a decision about where our portfolio was best applied,” he says, pointing out that existing HIV medicine is already effective. “My company has only so many things we can do. When I looked at HIV, they had done a lot of work trying to get a product. The current version … doesn’t feel like it is there.”

Sharp remains undaunted. After failing to get funds from Sangamo, he began lobbying U.S. government officials and HIV researchers. Thanks in part to his efforts, Rafick-Pierre Sékaly, a professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, was inspired to continue gene-editing research on HIV. The National Institutes of Health awarded Sékaly $11 million earlier this year for a new experiment called TRAILBLAZER that pays Sangamo for access to its gene-editing technology.

Sharp “has always been extremely passionate. He has always been very forceful, pushing us to do more,” Sékaly says. Now, a new cohort of HIV patients are joining Sékaly’s experiment. They are helping open up a future where gene editing could be a routine part of medical care.

Exactly what this future might look like remains to be seen. “If we could all be engineered to resist HIV,” Sharp says, “then the stigma associated with the disease might completely disappear.” If the technology becomes more effective, then a wide range of genetic diseases could be fixed. But gene editing carries other risks, besides technical problems. Existing gene therapies are very expensive, up to $475,000 per treatment. Gene editing could produce a new era of inequality in medicine, to say nothing of the fears some people have of “designer babies” or controversies about children engineered to resist HIV from birth.

There are subtler, more surprising possibilities, too. Tim Dean, a queer theorist known for flipping conventional scripts, speculates that gene editing could create a new class distinction among gay men in hook-up culture.* “In some techno-future, I can imagine cruising apps including a category, in addition to HIV status, that would differentiate the edited from the unedited,” he says.

Sharp, for his part, just wants to see research on a cure move forward. He doesn’t care if the cure is DNA editing, an antibody, or a new pharmaceutical drug. “I have already volunteered for 12 clinical trials,” he says, “and I am willing to try anything new if it looks like it might work.”

* This article previously misstated Tim Dean’s HIV status. We regret the error.

The Trump administration has unexpectedly decided to rapidly withdraw U.S. forces from Syria, where they have been fighting ISIS. This decision, which demonstrates that the president’s National Security Strategy does not govern his policies, will have deleterious effects across the strategic waterfront: throwing Syria policy into chaos; rewarding Iranian regional destabilization and Russian intervention; alarming Kurdish forces and American allies fighting in the region, as well as countries to which jihadists might return; and calling into question America’s commitment to stabilizing Iraq and Afghanistan.

All of these priorities have been capriciously sacrificed by President Trump for no apparent reason other than that he campaigned on withdrawal and wants it to happen now. There has been no precipitating event to drive a policy change. The president explained himself on Twitter as follows: “We have defeated ISIS in Syria, my only reason for being there during the Trump Presidency.” But that is at wide variance with National-Security Adviser John Bolton, who only three months ago publicly affirmed that the administration would remain indefinitely to prevent Iran from gaining further influence and posing greater threats.

While the announcement was unexpected, the president has been telegraphing his unhappiness with Syria policy for some time. Last spring, he said, “I want to get out. I want to bring our troops back home.” The Pentagon won a reprieve of “months, not years,” and evidently those months ran out yesterday.

[Read: Trump wanted out of Syria. It’s finally happening.]

Perhaps the president felt boxed in by establishment national-security figures early in his presidency, as previous presidents have felt boxed in, and those advisers have either been replaced or fallen from favor. But the lack of a process to evaluate the consequences of the policy change, and sync America’s actions with those of the 78 other countries contributing to the counter-ISIS campaign, will distress those who are risking their forces and security.

Kurdish forces in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey will be immediately and negatively affected by the decision. The contradiction inherent in the previous policy was that the United States armed and relied on Kurdish military forces that the Turkish government considers terrorists. But the U.S. has not been able to find common cause with Turkey in six years. By abandoning the Kurds—who do share American objectives—the U.S. leaves them to the mercies of Turkey even as it leaves Syria to Iran and Russia. Erdogan, Putin, Assad, Khamenei, and Soleimani must be drunk with their good fortune.

This decision will also unsettle every ally that relies on American security guarantees. The governments of Iraq and Afghanistan ought to be very, very worried. For if Syria can be so lightly written off, the fight arbitrarily declared won, what is the argument for continuing to assist Iraq—where ISIS is even more defeated? And if Trump has so little interest in stabilizing security and assisting governance in Syria, how can Afghanistan have confidence that he won’t make the same decision about them, when the fight there is costlier and progress less evident?

[Hassan Hassan: ISIS is poised to make a comeback in Syria]

White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders announced, “The United States and our partners remain committed to eliminating the small ISIS presence in Syria that our forces have not already eradicated.” Keeping allies in Syria will be a neat trick, given that the Trump administration had been twisting arms and promising an enduring American commitment. France and Britain are left exposed, as they may not be able to unwind their operations on America’s timeline. And they will fear that jihadist fighters will return to Europe if they are not tied down by operations on Syrian battlefields.

The president’s national-security strategy states, “The campaigns against ISIS and al-Qa’ida and their affiliates demonstrate that the United States will enable partners and sustain direct action campaigns to destroy terrorists and their sources of support, making it harder for them to plot against us.” President Trump’s decision yesterday proves that irrelevant.

It also makes irrelevant the Trump administration’s only persuasive claim to having improved on the Obama administration in the realm of foreign policy: It lifted the time constraint imposed on U.S. operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. The Trump administration had admirably insisted that achieving American objectives should drive the timeline of its wars, not vice versa. Now the only distinguishable difference between the retrenchment of American power practiced by President Barack Obama and the retrenchment practiced by President Trump is that Trump behaves so erratically that the cost to the U.S. and its allies is even higher.

About 75 million years ago, in what is now Alberta, Canada, a dinosaur called Euoplocephalus took its final breath. That exhalation, like every other, was fleeting and insubstantial, but eons later, scientists can still reconstruct the path it took out of the dinosaur’s head. And that path, it turns out, was extraordinarily convoluted.

Euoplocephalus was one of the ankylosaurs—a group of tank-like species covered in bony plates. Their skulls and backs were armored. Their eyelids were occasionally armored. Even the nasal passages inside their skulls were lined with bone, preserving these delicate structures, usually lost to time.

More than a century ago, paleontologists first noticed that those passages included a weirdly complicated series of chambers and tubes. They interpreted these as a set of sinuses that branched from a simple central channel—a slightly more elaborate version of the setup that exists inside your nose. But in 2008, Lawrence Witmer and Ryan Ridgely from Ohio University worked out what was really going on when they put the skulls of several ankylosaurs in a medical CT scanner.

The scans revealed the unusual structure of the creatures’ nasal passages—not sinuses forking off a central channel, but a single airway that repeatedly twists and turns, like roller-coaster tracks or a Krazy Straw. These passages are more complex than the airways of other backboned animals, and they’re remarkably long. The skull of Euoplocephalus “is the length of your arm from the wrist and elbow, but its nasal passage, if stretched out, would run from your shoulder to your fingertip,” says Witmer. “I remember standing up at a paleontology meeting, holding up my hands, and saying, ‘I don’t believe it, but this is what we got.’”

[Read:] A dinosaur so well preserved, it looks like a statue

Witmer and Ridgely thought that these convoluted airways acted as an elaborate air-conditioning system for the ankylosaurs’ brains. These were big, car-size animals whose bodies would have retained a lot of heat in the Mesozoic sun. “Hot blood would have come up from the core of their bodies to their brains,” says Witmer. “And while these dinosaurs’ brains were famously small, they were still brains.” Brains are especially sensitive to rises in temperature, which is why confusion and fainting are among the first signs of heatstroke. So how did ankylosaurs and other giant dinosaurs keep their noggins from cooking?

It was all in the nose, Witmer guessed. The vessels carrying blood from an ankylosaur’s body to its head ran alongside its long nasal canal. Every time the dinosaur inhaled, cool air would have meandered through that twisty airway, absorbing the heat from the adjacent blood and cooling it before it hit the brain.

WITMER lab / Ohio University

WITMER lab / Ohio UniversityWitmer’s colleagues Jason Bourke and Ruger Porter have now tested this idea. They used medical scanners to create digital replicas of the skulls of two ankylosaurs—Euoplocephalus and Panoplosaurus. Then they simulated the flow of air through these virtual noses, using techniques that are more commonly used by aerospace engineers.

These simulations revealed that, on an inhale, the dinosaurs’ long nasal passages gradually heated air by up to 36 degrees Fahrenheit, taking it from room temperature to body temperature and substantially cooling the adjacent blood. When the dinosaur exhaled, along the same twisty tubes, the air would return most of that heat back to the body. (Our own simple noses work on a similar principle, which is why your breath feels hotter coming from your mouth than from your nose.)

The team members also played around with their virtual skulls. In one experiment, they gave their ankylosaurs short and simple airways, much like ours. In another, they straightened the animals’ airways so they kept their normal length but lacked any twists. In both cases, the heating effect became far less efficient. Inhaled air picked up less heat, and it did so at the very end of the passages—too late to cool the adjacent blood vessels. It’s the passages’ length and their curviness that make them efficient air conditioners.

Read: [Meet Zuul, destroyer of shins—a dinosaur named after Ghostbusters]

“This is a fascinating deep dive into an aspect of dinosaur biology that’s been difficult to study—how a dinosaur’s breath traveled through its skull,” says Victoria Arbour, an ankylosaur expert at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. “It makes a lot of sense [especially since] many ankylosaurs lived in arid or tropical environments. It’s easy to see how this adaptation arose.”

Matthew Vickaryous from the University of Guelph notes that of the two species that the team studied, Euoplocephalus was bigger and had more complex nasal passages. Are those two things related? Do bigger species, which are more likely to suffer from overheating, need twistier noses? What kind of zany structures lurked inside the snout of the largest ankylosaur—the eponymous, eight-meter-long Ankylosaurus? Today it’s possible to answer these questions, because “CT data are now available for an increasing number of ankylosaurs,” Vickaryous says.

Tetsuto Miyashita from the University of Chicago agrees. He credits Witmer’s team for “pioneering a new genre in paleontology” in which they fuse the hard physics with messy biology. “What’s next?” Miyashita asks. “Well, no one has reconstructed resonation in those virtual nasal airway models to see whether [the passages] work like a trumpet. I hope they give that a try.”

After the Obamas shook hands with the Trumps at George H. W. Bush’s funeral earlier this month, Jemele Hill analyzed the implications of the phrase Michelle Obama coined in 2016: When they go low, we go high. “I sometimes wonder,” Hill wrote, “if the people who often cite that quote have a full understanding of the emotional toll it takes on people of color to have to constantly absolve the racism directed at them.”

Jemele Hill’s column on the Obama family’s class in dealing with Donald Trump at former President George H. W. Bush’s funeral is, and will remain, a classic. Citing the recent history of young Jeremiah Harvey, she beautifully described what most every African American I know experiences, in some form, on a daily basis.

For some of us, the experience she described has reached it limits. However, we, like President Barack Obama and the first lady Michelle Obama, must remain dignified and respectful in our responses. I’d like to share the advice of three icons: the late Dr. Arthur L. Johnson, one of my mentors; the late Zora Neale Hurston, a prominent African American author and anthropologist; and Bernard Lafayette, one of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s protégés.

When I was named public relations director at Eastern Connecticut State University in 1990, Johnson, knowing how whites have a difficult time accepting a person of color in charge, told me: “Dwight, you’re gonna have to eat some crow some time, and even take some stuff, but you don’t have to take it lying down.”

Hurston offers similar advice: “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”

Lafayette specifically counsels victims to know the law. When he spoke at Eastern Connecticut State University in 2013, he said: “If you don’t use your God-given rights, you will lose them.”

All three were and are right. Have a bone in your back. Be honest and firm, and if necessary, take people to court who commit their vicious and insidious acts and who behave disrespectfully toward you and expect you to “get over it.” Your beautiful prose shows that African Americans will always show class in facing and dealing with small-minded people.

Dwight Bachman

Willimantic, Conn.

I wonder if Ms. Hill considered the agency that both former President Obama and the first lady Michelle Obama exhibited rather than assuming that grace is weak. Of course grace, which means acting in love even when others don’t deserve the act, is formidable among the great exhibitors of social change. We wouldn’t expect less of these two. It is the strongest response and most revealing when standing next to those who have, in fact, been ungracious.

Rev. Jan Todd

Mulvane, Kan.

Thank you for your candid thoughts. I can identify with the article. As a father of a mid-20s, half-black man, no matter how hard I tried to raise him right and make sure he understood that heroes come in all colors and sizes by educating him through books and conversations, still at times I was frustrated that the reality of our society systematically enforces otherwise.

Combiz Khatiblou

Santa Clara, Calif.

As a woman of color, I am inclined to disagree that there was a problem with the Obamas’ “going high.” My perception of the Obamas is they are “high,” simply that. My take: The Obamas are not in the game. It is just not their style. And what do they have to prove by being obnoxious or belligerent?

Dr. Francine Adams

Lake Worth, Fla.

I disagree entirely with this. I’m partly African American myself, and I teach African American history. The behavior of the Obamas at the funeral was both appropriate and exemplary, in my view. As always, they conducted themselves with dignity and poise, despite Trump’s boorish conduct, and thereby illustrated precisely the sort of graceful bearing for which the late President Bush has been so highly praised.

Brian Alnutt, Ph.D.

New Tripoli, Pa.

I totally disagree with the author. The Obamas’ “going high” is for me one of the few things that can ameliorate the pain of watching the current president and his gang. Because “going high” is more than a chosen behavior; it’s an expression of character that elevates them, and by contrast, reveals the difference between them and the current president. I can’t imagine a worse response than to imitate the president in his emotionally stunted words or behavior. Their “going high” makes me proud and humbled at the same time—proud for their example and humbled at my own failures under less provocation.

R. B. Goetsch

Pioneer, Calif.

The essay by Ms. Hill encapsulated precisely what I was thinking, but could not articulate. I have felt conflicted by the Obamas for many years. To my mind, if a person looks out the window and says it’s raining and another says it’s sunny, it is the job of a leader to look at the evidence (in this case, look out the window) and speak the truth, not cite them both. Yet most blacks understand that, in a country where the lion’s share of resources is controlled by Caucasians, the inherent nature of white supremacy demands we be exemplary. The Obamas understood that racism is as American as apple pie. So much so, the most minor attack on it risked many Caucasians thinking it was an attack on America. This was a risk they were not prepared to take.

However, there is a significant degree of cognitive dissonance involved in taking the high road. Marginalized groups are told to be patient, polite, and civil in the face of the most grievous assaults and, when they hazard to make even the most minor of pleading, are invariably ignored. For marginalized people, the irony is not lost that they are told to do things the “proper way,” knowing America was founded on, oftentimes, very violent protest and conflict. Moreover, when affluent Caucasians are riled up over some perceived slight, they seem to have no problem doing whatever is necessary to preserve and sustain their position in society.

I’ve stopped thinking that if I am palatable enough, European Americans will open their arms to me, and that I will have fair access to opportunities if my personage is more pleasing to white sensibilities. It has not worked, and this is emotional labor I no longer have the strength, nor the inclination, to expend. It is not my responsibility to make European Americans feel more comfortable with me. For me, the old tenet of power conceding nothing without a demand is truth.

Connor Smithersmapp

Halifax, Nova Scotia

What immediately stands out in Peter Jackson’s documentary They Shall Not Grow Old is the faces of its subjects. A painstaking restoration of century-old video footage from the First World War, the film is a complex project with a simple goal: to try to convey what it was like to live and fight on the Western Front from 1914 to 1918. But the technology Jackson deploys is so advanced that the documentary, which has been colorized and enhanced, captures a surprising degree of character and realism. The British soldiers’ faces smile, wrinkle, and grimace—all without the artificial, sped-up look typical of archival cinema.

“You recognize the minutiae of being a human being; it suddenly comes into sharp focus,” Jackson said in an interview with The Atlantic about how his film—quite literally—offers a different way of seeing the men who fought in World War I. “You realize, for 100 years, we’ve seen these guys at a super-fast speed, full of grain, jerky, jumping up and down, which has completely disguised their humanity.” In creating They Shall Not Grow Old, a five-year process carried out in tandem with the British Imperial War Museums and the BBC, Jackson tried to emphasize that personal touch, crafting a documentary experience that’s far more immersive and tactile than most.

Though They Shall Not Grow Old has already aired on British television, it is best seen in a theater—it will play limited special engagements in North America on December 27. The film is being screened with eerily impressive 3-D projection that adds an extra layer of verisimilitude, but to Jackson these added presentation elements aren’t the main draw. More significant is the restoration itself, which was completed by his company WingNut Films, the main force behind his effects-driven Lord of the Rings and Hobbit movies. (An American company called Stereo D did the colorization and 3-D conversion for They Shall Not Grow Old.)

When the Imperial War Museums first contacted Jackson and handed him 100 hours of raw footage, it asked only that the video be presented to audiences in a “fresh and original way,” without any new material from the modern era. Unsure at first how to translate those instructions into a full-fledged documentary, Jackson began by tackling the restoration. During World War I, footage was shot on hand-cranked, black-and-white cameras, usually at 10 to 12 frames per second, which creates an “over-cranked” (or sped-up) visual when the film is played at the 24-frames-per-second standard of modern cinema.

“I set about doing four or five months of testing with a little piece of film that [the Imperial War Museums] sent, and I was amazed at the results,” Jackson said. “It was so sharp and so clear, it looked like it was shot now. It was way better than I ever dreamt it could be.” The director and his team carefully filled in the frame gaps, removed damage from the footage, and hired lip-readers to discern what people were saying so that dialogue could be dubbed in along with sound effects. “To me, the colorizing is the icing on the cake,” Jackson said. “But the transformation happens when you take away all that damage and get [the soldiers] moving at a normal human speed. They become real people again.”

[In photos: The fading battlefields of World War I]

Only after beginning the restoration did Jackson hit upon the idea for the documentary’s unique presentation: The film would focus exclusively on the trench warfare of the Western Front, and it would be narrated only by audio interviews conducted in the 1960s and ’70s with British soldiers who fought on those battlefields. “[Our goal] really became, at that point: We’ve got to show the war as the soldiers saw it,” Jackson said.

They Shall Not Grow Old doesn’t try to encompass every aspect of the massive conflict that was World War I, avoiding the potted-history approach of many documentaries. “I didn’t want to impose my own ideas on [the film]. I wanted to listen to everything on the audio interviews, to look at all the footage, and to let that find its own shape,” Jackson said. “To be quite honest,” he added, “the 100 hours of footage could make up seven or eight entirely different films.” So he ended up setting aside material about the air force, the naval battles, the women-led efforts in U.K. factories, and farther-flung engagements such as the Gallipoli campaign, knowing he wouldn’t be able to do them justice with one film.

Jackson was thus able to take a more slice-of-life approach to his subjects. “The mundane parts of being on the Western Front are the most interesting. These soldiers, they couldn’t talk about the history of the First World War, they couldn’t talk about the strategy and tactics,” he said. “There’s one guy who says [in an interview], ‘All we knew is what we could see in front of our eyes. Everything else, to the left, to the right, we had no clue.’ That myopic, super-detailed … view became the story that I should tell. It’s a story you don’t often see in the history books and the documentaries. It’s what they ate, how they slept, how they went to the loo, what the rats and lice were like. The comradeship, the friendship.”

The film begins with soldiers recalling what it was like signing up for the war (and acknowledging their limited understanding of the conflict), going through basic training, living in the trenches, and going “over the top” into the nightmare of no man’s land. As a sort of oral history with expressive visuals, They Shall Not Grow Old succeeds at putting the viewer into the middle of a distant period. I was personally taken aback by the profound sense of camaraderie on display, by the grins on people’s faces despite the bleak surroundings, and by the genuine compassion that many British soldiers expressed for their German counterparts.

“You listen to these guys, and you realize they don’t consider themselves to be the victims that we have turned them into,” Jackson said of the film’s subjects. “They don’t want our pity; they don’t feel self-pity. They were there, they chose to be there, they made the best of it, and for some of them it was a period of intense excitement … Some of them even thought it was fun. That surprised me.”

Still, the film doesn’t hold back in its depiction of the brutality of trench combat, and how most British soldiers started seeing the war as a pointless effort the longer it dragged on. “The strongest opinion they would have had was, ‘The German army’s in Belgium and France, and we’re coming over here to push them out because we’re friends [with Belgium and France],’” Jackson said. “I don’t think people could quite get their heads around why the British and the Germans were suddenly enemies.” As the conflict winds down and more prisoners of war are taken, testimonial after testimonial in They Shall Not Grow Old suggests that British soldiers saw little difference between themselves and their supposed adversaries.

“They were dealing with the same hardships, eating the same crappy food, in the same freezing conditions, and they felt a sort of empathy,” Jackson said. “They were there because their governments told them to be there.” That empathy, mixed with a sense of futility, is what makes They Shall Not Grow Old such a precise triumph. Jackson takes whatever amorphous ideas the average viewer might have about the First World War and uses real human experience to give them shape. As the film’s hundred-year-old footage springs to life, each face—whether muddied, wearied, relieved, or overjoyed—suddenly belongs to a recognizable person again. It’s both thrilling and humbling to witness.

Updated at 5:22 p.m. ET

President Donald Trump is finally getting his way in Syria. Vehemently opposed to the extended presence of American troops in the war-ravaged country, he had been forced to keep them there longer than he wanted. Not, it seems, anymore.

“We have defeated ISIS in Syria, my only reason for being there during the Trump Presidency,” Trump said Wednesday on Twitter.

The tweet appeared to confirm news reports that the United States would withdraw the roughly 2,000 American troops stationed in Syria who are fighting the Islamic State group. The U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition has made significant territorial gains against the militant group, but has struggled to completely eliminate ISIS from a few pockets in Syria.

But if it is carried out, a U.S. pullout leaves open a question of the militants’ resurgence, and would delight at least two of Syria’s neighbors: Iran and Turkey. American soldiers might have been in Syria to fight ISIS, but they also served as a deterrent to the Islamic Republic, which supports Syrian President Bashar al-Assad with troops and militia fighters.

White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders said, “We have started returning United States troops home as we transition to the next phase of this campaign.”

A senior administration official, speaking on condition of anonymity, would not be drawn on when the troops would return, saying the administration would not discuss timelines of troop movements. Asked about concerns of ISIS re-emerging and an increase in Iran’s influence, the official maintained U.S. forces would “continue the fight against ISIS” and, citing the administration’s sanctions against Tehran, said “Iran knows the U.S. stands ready to re-engage at all levels to defend American interests.”

The announcement Wednesday was in stark contrast to senior U.S. officials’ recent remarks on the presence of troops.

As recently as last week, the U.S. had other plans. Brett McGurk, the special envoy for anti-ISIS operations, was asked how long American forces would stay in Syria. “If we’ve learned one thing over the years, enduring defeat of a group like this means you can’t just defeat their physical space and then leave,” he said.

The American military operates in eastern Syria with the People’s Protection Unit, or YPG, a Kurdish militia group. Turkey says the YPG has links to the Kurdistan Workers Party, a Kurdish separatist group that operates in Turkey and is outlawed by the U.S. as a terrorist organization. Last week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said his troops would “start our operation in a few days” against the Kurdish group in Syria. The U.S. has a smaller presence in southern Syria.

The American withdrawal also bolsters Assad and his Iranian backers.

When the Syrian conflict began in 2011, for a while he was expected to meet the same fate as other leaders ousted in the Arab Spring. Backed by Moscow and Tehran, he remains secure more than seven years later. What’s more, the U.S. is no longer insisting on a Syria without Assad.

James Jeffrey, the American special representative in Syria, said Monday the U.S. would fund Syria’s reconstruction only if the regime is “fundamentally different.” But he immediately added, “It’s not regime change. We’re not trying to get rid of Assad.” He acknowledged that while the U.S. wants Iranian troops to leave Syria, Tehran would continue to exert influence with Damascus.

Jeffrey’s remarks at the Atlantic Council followed two regional developments that signal the beginning of Assad’s rehabilitation: On Sunday, Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir became the first member of the Arab League to visit Syria since the civil war began in 2011. Bashir, an international pariah because of his role in the Darfur conflict, is unlikely to have met with Assad without regional blessing. Subsequent news reports said Assad would likely be invited to the next Arab League summit meeting, a boost for the dictator, who was expelled from the organization over the conflict.

Perhaps more significant, Turkey, which armed and funded rebels fighting Assad, said it would consider working with the Syrian president if he won a democratic election. Jeffrey implied Monday that the standard wouldn’t even have to be that high: Assad, he said, mustn’t use chemical weapons or torture Syrian citizens.

“It doesn’t have to be a regime that we Americans would embrace as, say, qualifying to join the European Union if the European Union would take Middle Eastern countries,” he said.

As recently as October, the Trump administration’s stated goal in Syria was for Syrians to “establish a new government that is not led by Assad.” But there is now recognition that the conflict is no longer restricted to the regime fighting the rebels—or indeed the U.S. clashing with ISIS.

Russia has invested heavily in Assad and is unlikely to succumb to outside pressure that could weaken its interests. Iran, whose regional actions are the focus of the Trump administration’s Middle East policy, is a different case. Jeffrey said Iranian troops must leave Syria, even while acknowledging Tehran’s role. “Iran will have diplomatic influence in Syria,” he said. “It’s had it for many decades. It will have more now.” With a U.S. withdrawal, that influence will now almost certainly increase.

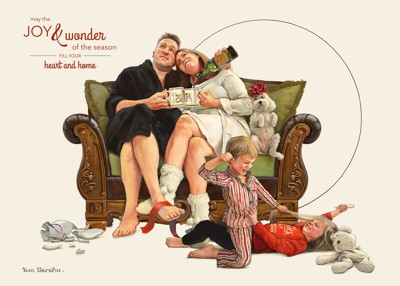

Six years ago, Ken Sarafin created his inaugural family Christmas card. Harnessing the aesthetic of Norman Rockwell—the 20th-century painter known for conveying the everyday life of Middle America—Sarafin illustrated a portrait of his sister, her husband, and their then-newborn daughter. The painting showed Sarafin’s niece crying on the floor, with her father nearby wearing a disheveled tie and drinking a martini, and her mother talking on the phone while mixing something in a bowl; in the background sat a small, scraggly, Charlie Brown–esque Christmas tree. “We were kind of going for 1950s Americana and its traditional gender roles on that one,” Sarafin recently told me.

Ken Sarafin’s sister’s 2017 card (Ken Sarafin)

Ken Sarafin’s sister’s 2017 card (Ken Sarafin)At the time, Sarafin—a 33-year-old graphic designer in Denver who doesn’t have children of his own—saw the card as a fun opportunity to put his painting hobby, and his newfound affinity for Rockwell’s style, to use. It was also a way to bond with his family—and to poke fun at the classic family holiday card, with its matching sweaters, forced smiles, and feigned peace. Sarafin and his sister had never been fans of “Christmas cards that are overly cheesy and cutesy and look how great our family is,” he says. He’s illustrated a similar portrait of his sister’s family in disarray every Christmas since.

Americans today are sending far less snail mail than they used to: The overall volume of physical mail in the United States has dropped 43 percent since 2001, according to the U.S. Postal Service. But one form of conventional mail that has somewhat bucked this trend is greeting cards—especially family holiday cards. While the rates of sending cards have declined slightly, today’s Americans buy 6.5 billion greeting cards annually, according to data from the Greeting Card Association. Of those, 1.6 billion are for Christmas, the largest card-sending holiday in the country. And greeting-card mail, it seems, has declined at a much lower rate than overall mail.

Industry data suggest that interest in family holiday cards is on the rise. For example, Google data procured by Shutterfly, a nearly 20-year-old online company whose products include customized photo cards, show a steady increase in the number of queries for family Christmas cards. Etsy, the online marketplace where artists can sell handmade products, has seen a similar uptick: From September to November of this year, the number of searches on the site for custom cards, like those featuring personalized family portraits, was 258 percent higher than it was last year during the same time range, a company executive told me.

These data, experts agree, hint that Millennials are a key component of holiday cards’ staying power. Millennials are the target demographic for sites such as Etsy, as well as newer custom-card companies such as Minted. And while people of all ages participate in the tradition, people tend to start sending holiday cards when they hit a milestone such as marriage or a first child—and Millennials are the generation currently hitting those landmark events. Although the USPS report found that the decline in snail mail is especially pronounced among these Millennials, it also identified this generation as the demographic that could save the post. Amanda Stafford, a co-author of the report, suggests that the Postal Service ought to leverage young Americans in part because the lower volume of the mail they receive makes each piece of correspondence more special. Stafford says this age group may be especially drawn to the personal touch—the handwriting, the tangible photos, the labor of addressing and placing postage on an envelope—that only conventional mail can provide.

According to data from Hallmark, Millennials represent nearly 20 percent of the dollars spent on greeting cards, and their spending is growing faster than that of any other generation. And according to focus groups convened by the company, 72 percent of Millennials enjoy giving cards, while 82 percent enjoy receiving them; a similar number of young adults today typically save the cards they receive, too. Consumer research conducted by other card companies echoed these results. “People use so much less paper these days that when they do use paper, they want it to be really nice and special,” says Mariam Naficy, the founder of Minted, an online marketplace that crowdsources designs for photo cards. The rarity of snail mail, Naficy suggests, makes personal correspondence such as family holiday cards more meaningful. One young adult I spoke with—Alison Cuevas, whose card this year features an image of her and her two rescue pets against a galactic backdrop—described such correspondence as a “novelty.”

Social-media fatigue was a common theme across my conversations—it’s just nice sometimes to get a message from a far-flung loved one that doesn’t entail looking at a phone. “You’re more connected than ever, but in the same way, it’s all transitory connection,” says Mickey Mericle, Shutterfly’s chief marketing executive. “People feel this ephemeral connection, and they want to make it meaningful and lasting at certain points of the year … Holidays are a perfect time for that.”

The photo for Yuliya Goloida’s 2018 card (Igor Tchoudinov)

The photo for Yuliya Goloida’s 2018 card (Igor Tchoudinov)Young adults such as Sarafin highlighted the value of the tactile experience of cards, of the way they allow a degree of personalization that can’t be replicated on social media. “Anything you post on a digital platform gets buried by all the other digital things around it,” says Yuliya Goloida, a 23-year-old graduate student in Toronto whose card this year features a picture of her, her boyfriend, and her black cat Tusya. A family holiday card, on the other hand, is a “tangible memory that is protected from the bombardment of other images—it brings back the privacy and personal aspect” of photos, Goloida told me.

It’s no wonder, then, that consumer researchers have noticed customers gravitating toward old-fashioned aesthetics—echoing the surging popularity, more generally, of gifts such as wooden toys, for example, and items made to look like cassette tapes. Of particular appeal these days are customized cards featuring plaid or white borders evocative of Polaroids, according to Minted’s Naficy.

But while some are keeping it traditional, others are embracing sillier aspects of the holiday card. As Naficy puts it, there’s been “a movement away from formality toward informality.” Christmas cards became popular in 20th-century America in part because they served as a means of signaling a family’s prestige—hence the (bygone) trend of sterile, overly stylized portraits of the clan in front of, say, the fireplace, or of a generic backdrop courtesy of Sears. But times have changed, and these days family holiday cards will typically feature just one such photo, if any, Shutterfly’s Mericle told me. “The rest are silly—they’re everyday moments, they’re spontaneous,” she says.

Read: How Millennial parents are reinventing the cherished family photo album

While children are still the most common characters on holiday cards—data from Minted suggest that kids appear in three-fourths of today’s family holiday cards, for example—the definition of family has steadily expanded. Goloida says that when she was growing up, she dreamed of partaking in the tradition by having a family of her own pose and dress up for photos. But in her early 20s, she didn’t want to wait anymore and decided that she, too, could send out Christmas cards—even if she didn’t have a husband and kids. (Last year’s Goloida-family Christmas card, the first of what she expects to be a lasting tradition, featured a photo of her and her now-deceased three pet rats.) Card-company representatives confirmed that a growing percentage of cards feature pets.

The photo for Alison Cuevas’s 2018 card (Alison Cuevas)

The photo for Alison Cuevas’s 2018 card (Alison Cuevas)Regardless, Christmas cards provide couples and families with a way to express their originality and remind their loved ones that they care with a fun, unique greeting. The irony is that this form of correspondence traces back to the mid-1800s, when a British civil servant—eager to clear a backlog of mail to which he felt obligated to respond in accordance with Victorian social norms—invented the idea as a crafty means of mass-distributing personalized correspondence.

Part of that original motivation lives on: Research has found that consumers want the creation of the cards to be as convenient as possible. So corporations such as Shutterfly and Hallmark are striving to make their services as seamless as possible—using AI to create photo collages, for example, or suggest ideas for customization so buyers don’t have to deal with the labor of sorting through their massive photo libraries.

Ryan and Mallory Wales, a couple in Indiana, made their inaugural holiday card this year, a few months after having their first children, twins. Ryan, 31, took the photo, deciding to go with dim Christmas-themed lighting because of the soft look; Mallory, also 31, used a smartphone to design the card, which featured the twins. But it wasn’t effortless, they stressed. “Even in our busy lives, we took the time out to do this—to actually put them together and mail them out,” says Mallory. “It’s just different from taking that picture and putting it on social media for the likes.”

The photo for the Waleses’ 2018 card (Ryan Wales)

The photo for the Waleses’ 2018 card (Ryan Wales)The convenience of the digital age married with the personal touch of snail mail may help the tradition last. “A Christmas card is just to show people that we know that we still have contact,” Ryan Wales says. “It’s always more personal than anything Facebook, Instagram, or even an email or text can deliver. And that’s the way I look at it: It’s kind of like we’re mirroring this old and new world.”

When I left Congress after four decades of service, my greatest regret was that we failed to address climate change. As the most pressing and critical challenge of our generation threatens species and civilization with unimaginable upheaval, our inability to legislate a federal solution is a national shame. We got as close as we ever have in 2009 when the American Clean Energy and Security Act was approved by the House of Representatives—in large part due to artful maneuvering by Speaker Nancy Pelosi. But the bill never cleared the Senate or reached President Barack Obama’s desk for signature.

A decade later, I’m encouraged that young progressives are joining with many of my longtime colleagues in Congress to renew the fight against climate change. Their call for a Green New Deal is smart, politically and substantively.

The frame is right—both economic and historic—and gets to the heart of what we were trying to do a decade ago: use the mechanisms of government to build a cleaner economy. A few small reforms won’t limit the rise of global temperatures; we need a massive movement on multiple fronts.

[Read: The Democratic party wants to make climate change exciting]

By definition, a Green New Deal must place green jobs and transformative innovation at its core. Policy makers will need to look at the industries that drove the 20th-century economy and reshape them for the 21st. They must show that sustainability is not just the right thing to do for the fate of our planet, but an unparalleled opportunity to ensure the prosperity of future generations. That is a hopeful message in a time when hope can sometimes feel out of reach.

But in the short term, the passage of even moderate climate legislation, much less something as bold as the Green New Deal, seems unlikely. So what can we do now?

Progressives can work in states where climate legislation is possible to showcase what a Green New Deal might look like. Already, California and Hawaii, among others, have invested heavily in renewable energy and committed to a carbon-free future. As the clean-energy economy in these states grows, a model for change on a national and global scale will emerge.

Progressives should also exert pressure on industries to help them recognize that sustainability is not only feasible but also smart business. As the price for wind and solar energy falls, and as international markets adapt to meet their obligations under the Paris accord, companies that source renewable energy will find themselves with a competitive advantage.

[Read: The new politics of climate change]

Even in traditionally “dirty” industries, like steel, it’s possible to see what the Green New Deal might look like. Most U.S. steel is produced by using enormous amounts of electricity to melt down scrap; a commitment by steel producers to power facilities with renewable energy would not only decrease their costs and make their products more attractive to international buyers—it would also boost markets for one of steel’s leading customers, wind-turbine manufacturers. It’s a virtuous circle.

Concurrently, investors and institutions must double down on funding the technologies that will make a green economy more viable—from renewable power to more sustainable agriculture to advances in capturing and storing carbon that’s in the atmosphere. Climate change is here, and we will need these tools to mitigate the damage already done.

Lastly, congressional Democrats can use the powers they do have—control of one chamber and the ability to conduct investigations—to show Americans what an alternative path might look like: one in which green jobs are created across the country, where we commit to cleaner, renewable power, and where we invest in the next generation of American industries, all while holding accountable those who seek to profit from practices that jeopardize the future of our species.

And perhaps it goes without saying, but we must assess what’s working and what’s not. We’ve made missteps in the past, perhaps most notably with federal mandates for food-based biofuels. Ethanol and biodiesel seemed cleaner than fossil fuel, but it is now clear that their production is driving the destruction of carbon-rich ecosystems in the United States and abroad.

While the American Clean Energy and Security Act never found its way into law, a decade later, I see its spirit alive and well in a new generation’s call for climate progress.

Here is the plot of the 2018 Lifetime film A Very Nutty Christmas, as summarized by the network that airs it:

Hard-working bakery owner Kate Holiday (Melissa Joan Hart), has more cookie orders than she has time to fill this holiday season, and when her boyfriend suddenly breaks up with her, any shred of Christmas joy she was hanging onto, immediately disappears. After Kate hangs the last ornament on the tree and goes to bed, she awakens the next morning to a little bit of Christmas magic. She gets the surprise of her life when Chip (Barry Watson), a handsome soldier who may or may not be the Nutcracker Prince from Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, appears in her living room.

This description, despite its zaniness—I would like to take this opportunity to reiterate that this enchanted nutcracker, ostensibly constructed of wood and also coming to life in the home of a bakery owner, is named Chip—doesn’t quite capture the particular kind of film that A Very Nutty Christmas is. The Hallmark holiday movie, whether it happens to be airing on Lifetime or on Freeform or on Netflix or, indeed, on Hallmark itself, is a genre that transcends its network. And, via a magical nutcracker, here it is on Lifetime, distilled down to its essence. There’s the small town and its quaint bakery. There are softly lit Christmas cookies. There’s a climactic Christmas pageant (in this case, a Christmas ball), and ice skating, and lots of snow, and liberal musical use of “The Nutcracker Suite.” And there’s a classic protagonist of the genre—a woman who is frazzled, but who does not need to be—who faces, as Lifetime’s summary suggests, the gravest threat these films can imagine on behalf of their heroines: Kate Holiday, yes, is in danger of losing her Christmas Spirit.

“There’s no Christmas for me this year, okay?” Kate tells her best friend and bakery assistant, Rosa (Marissa Jaret Winokur), after her cad of a boyfriend admits to cheating on her. “I’m just going to muddle through the holidays myself.”

This, when uttered in the context of a Hallmark holiday movie, is a beacon to the Christmas spirits, who know one thing, and pretty much one thing only: No one should simply muddle through the holidays. Whether you celebrate Christmas or not—however you find meaning in the time of year that these movies shorthand as “the season”—the ideal, these films insist, is unmitigated joy. Christmas, here, isn’t a religious observance or even a seasonal festival; it functions, often, simply as a deadline: the day by which, in the framework of the films, it is no longer tenable to keep putting off the thing that will bring that joy, whether it’s a declaration of love or an apology or a reunion or the rediscovery of one’s Christmas Spirit.

The Hallmark film, during a time when so much television is anxious and moody—when so much television, that is, is reflective of the world itself—takes residence in an alternate reality. It will not let you, dear viewer, merely muddle through. It wants so much more for you. It wants love. It wants fulfillment. It wants magic. The genre, the snow globe in video form, offers its own kind of reassurance: of order, of ease, of predictability itself. Within its contained universes, happy endings are not only possible, but also insistently inevitable.

For Melissa Joan Hart, who executive-produced A Very Nutty Christmas in addition to starring in it, that’s a big part of the point: The joy of these movies is their consistency. “They’re sort of predictably charming,” she told me. You could think of them, she added, as very seasonal soap operas, with their fusions of certainty and surprise. They’re aggressively comforting. They’re the kind of light fodder you can have on in the background at home as you’re wrapping presents or getting ready for guests or, say, baking cookies. The films can function “like a soundtrack to your life during the holidays,” Hart says.

That does a lot to explain why these plentiful and relatively low-budget movies are so popular. This is a year that finds Netflix dabbling once more in the genre, with princesses switching places and lifestyle bloggers becoming princesses. It is a year that finds Freeform (the renamed network ABC Family) getting in on the holiday action. The movies they air aren’t merely plays for the audiences of 2018, but also investments in the networks’ futures: One of the features of the made-for-TV holiday movie is that the genre is, compared with others, relatively timeless. New titles blend with old ones, creating, once you’ve been at it for a while, a back catalog that allows for endless recycling. (Hallmark, for example, is airing 22 original movies for the first time this year, but the network’s library of earlier films consists, according to one count, of 232 titles.)

And the casts of the movies, finally if extremely belatedly, are expanding beyond the Candace Cameron Bures and Alicia Witts and other white leads to become more representative of the world at large. Mariah Carey starred in a Hallmark movie, the aptly named A Christmas Melody. Tatyana Ali starred (with Patti LaBelle!) in Christmas Everlasting. Tia Mowry-Hardrict starred in A Gingerbread Romance. (As for rom-com plot lines that revolve around queer pairings? That will have to wait, it seems, for another time.)

Recent entries in the genre have also adopted a certain self-consciousness: There’s often a heavy dose of irony woven into their formulas—the comfort of the weighted blanket mixed with the winking absurdity of the ugly Christmas sweater. In A Very Nutty Christmas, Chip, adjusting to life in the America of 2018, brings some classic fish-out-of-water jokes: He wields a wooden sword (believing his mission to be protecting Kate from the Mouse King, he is ever ready to do battle). He jovially breaks out into renditions of “O Tannenbaum” at inopportune moments. He is also—à la Buddy in Elf, another fish who finds himself suddenly landlocked—excessively fond of sugar.

Chip soon proves himself, as well, to possess a superhuman ability to crack nuts (with his palms, his fist, his flexed bicep)—a development that, after Rosa takes a video of him at work and posts it, makes him, briefly, an Instagram star. And he gets Kate out of a professional jam: Her mechanical nutcracker breaks, and she needs to make nut flour in order to make her cookies. “At your service,” the anthropomorphized kitchen gadget tells her, before putting himself to use.

The absurdity, too, is the point. A movie that titles itself A Very Nutty Christmas is, after all, in on its own joke. It refuses to take itself too seriously, and invites you not to take yourself that way either. And that, during a time of year that can be Magical and Joyful but also pretty Stressful, is its own kind of relief. How, precisely, will Kate give herself over to the magic that has brought this hunk of wood into her life? Will Chip remind her of the joys of the season? Will he save her from the Mouse King? I won’t spoil any of it, but also I am incapable of spoiling any of it: The promise of a Hallmark-style holiday movie is that, effectively, it cannot be spoiled.

Until two weeks ago, T. M. Landry College Preparatory School was the most enigmatic school in America. Small and with minimal resources, this private school was known for one thing: placing an extraordinary number of black, low-income students in America’s most elite colleges and universities. Almost everything else about it was mysterious.

The school’s founders and namesakes, the married couple Tracey and Michael Landry, had promoted it via a series of viral videos. In each of the videos, a young student, usually black, waits in suspense, surrounded by classmates, to find out if he or she has been admitted to a top college—Princeton, Dartmouth, Yale, among others. Invariably, the student gets a happy answer, and the entire room erupts in raucous celebration.

T. M. Landry is in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, a high-poverty town of fewer than 10,000. The school’s graduates are overwhelmingly black, poor, or both—a socioeconomic segment that, due to pervasive discrimination, is notoriously underrepresented in higher ed. Statistically speaking, when a poor black student is admitted to a Harvard or a Yale, it’s a minor miracle. The odds of an institution sending graduate after graduate to the Ivy League and similar schools are infinitesimal. Watching T. M. Landry’s viral videos was akin to watching lightning strike the same spot not twice, but over and over again. Had the Landrys cracked the educational code?

[Read more: Why the myth of meritocracy hurts kids of color]

At the end of November, in a blockbuster story, The New York Times solved part of the puzzle. The Landrys’ school seems to have been a fraud all along—faking transcripts, forcing students to lie on college applications, and staging rehearsed lessons for curious media and other visitors. According to the Times, an atmosphere of abuse and submission helped maintain the deception, with Michael Landry lording over his flock of children like a tyrant. In the Times story, Landry admitted to helping children with college applications while denying any fraud. The school did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Still, a mystery remains. Even taking the alleged fakery into account, how did T. M. Landry seem to fool so many of America’s most prestigious universities for years? The work of admissions officers is notoriously secretive, but what little is known about the Landry affair threatens foundational assumptions about American higher education.

The key to the alleged T. M. Landry scam can’t be the quality of the deception, because it was far from airtight. If anything, the story the school told about itself should have sparked immediate skepticism.

This isn’t hindsight speaking; I know from experience. I first encountered the school's viral videos last spring, and as a researcher on race and education, I felt compelled to learn more. What I found immediately raised my suspicions. Outside the videos themselves, the school offered little coherent explanation of how its students managed to win the collegiate lottery so often.