“It’s harder than ever to hear music in a vacuum,” write Hannah Giorgis and Spencer Kornhaber. “In this info-swamped era, the sound coming out of the speakers will be processed in the context of broad stories (uh oh, is this song about Robert Mueller?) and personal ones (uh oh, is this song about my ex?).” The most indelible television shows, films, podcasts, and books of 2018 are colored with that same bleed of political and cultural significance.

What We Listened To (Illustration by Katie Martin)

(Illustration by Katie Martin)The 23 best albums of 2018

“Though Drake kept watch over the Hot 100 from the No. 1 spot for much of 2018, this year in music was not one of consensus.” → See the full list.

50 best podcasts

From a series about the history of conversion therapy in the United States to the jaw-dropping story of the neurosurgeon nicknamed Dr. Death, to a return to the events that led to then–U.S. President Bill Clinton’s impeachment in 1998, these most well-crafted shows of 2018 will keep your road-trip playlists spinning for a long time. → See the full list.

27 most memorable moments in music

The cultural effects of Nicki Minaj’s “Chun-Li,” Ariana Grande’s “No Tears Left to Cry,” Mitski’s “Nobody,” and more. → See the full list.

Illustration by Katie Martin

Illustration by Katie MartinThe 22 best television shows of 2018

Both new and returning series, from an adaptation of a fiction podcast thriller to a light but philosophical comedy. → See the full list.

25 best individual television episodes

Standouts from Atlanta, One Day at a Time, The Terror, Homecoming, The Great British Baking Show, and more. → See the full list.

17 best films

“While 2018 was not a big year for big films, it was a big year for smaller ones. Yes, A Star Is Born was a major hit, and deservedly so. But the bulk of the movies on our two critics’ lists were not Hollywood Oscar bait but intimate fables meticulously told.” → See the full list.

Illustration by Katie Martin

Illustration by Katie MartinThe 19 best books of 2018

“Highlights from a year of reading, including Ada Limón’s The Carrying, Tommy Orange’s There There, Madeline Miller’s Circe, and more.” → See the full list.

Our 7 favorite cookbooks

Pan-seared steak with za’atar chimichurri, curried lamb ribs, and a host of other inventive dishes from this year’s top food bibles. → See the full list.

This special edition of the Daily was compiled by Haley Weiss and Shan Wang. Concerns, comments, questions? Email swang@theatlantic.com

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for the daily email here.

As winter approaches in Finnish Lapland, daylight rapidly retreats. The Sami—the estimated 80,000 people who are indigenous to the region and live in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia—prepare for winter by bringing their reindeer down from the mountains. More than 7,000 reindeer herders, known as boazovazzi, or “reindeer walkers,” work together to herd 500,000 reindeer from their grazing pastures. Once the animals are down from the mountain, they are separated by their owners in large herding pens. Some reindeer go to the slaughterhouse, while others are kept for breeding. A select few males are neutered and trained to work, either pulling sleds or racing.

“I wanted to capture the eerie isolation of the Arctic landscape and the sheer adrenaline rush and excitement of the herding,” Eva Weber told The Atlantic. Weber’s short documentary depicts a three-minute slice of life as a Sami reindeer herder. The filmmaker fought the limitations of the project—only a few hours of light to film each day, a remote destination, cameras that constantly fogged due to the sub-zero temperatures, and sound equipment that failed in the cold—in order to capture the ancient tradition of reindeer herding in the North Pole. “It really was a very tough shoot.”

Encountering reindeer up close was a transformative experience for Weber. “The reindeer make the most incredible noises,” she said. “You can hear them from a long distance, and it is beautiful.” Once in the herding pen, Weber was struck by the energy of the animals. “I will never forget standing in the middle of the animals running around us in circles as they were being separated. We were standing in the path of the running reindeer and barely being brushed by them. Moving at that speed and with those antlers, it’s amazing how they manage to avoid obstacles in their path.”

According to Weber, Scandinavian folklore relishes in the mystery associated with Lapland. “It’s a land of magic and myths, ruled by the ancient animistic beliefs of the Sami,” she said. “According to Sami mythology, spirits are present in everything, from rocks and trees, foxes and reindeer, and the northern lights in the sky.”

“There is a dreamlike quality to the land, and for half a year, the landscape is transformed magically to resemble a wintry fairytale,” she continued. “During this time, you can’t tell whether you stand on land or lake, beneath the sky, or in it; you can see the color of the air and hear the hum of silence. There is something about isolation in an expansive space that blurs one’s boundaries.”

But if you are ever lucky enough to visit Lapland, remember to refrain from asking how many reindeer a Sami herder has. “It’s rude,” Weber said. “It is like asking a Westerner how much money he has in his bank account. The Sami say their money ‘roams around.’”

Yasuyoshi Chiba, a staff photographer with AFP, spent nearly the entire year of 2018 in Kenya, documenting an incredibly wide range of subjects, landscapes, and issues. Chiba has been on staff with AFP since 2011, winning multiple awards for his photojournalism, which is based mostly in Brazil and Kenya. This year, he captured the faces and stories of some of the 50 million people who live in Kenya, an East African nation of incredible diversity in culture, landscape, and wildlife. His photos cover subjects from a China-backed railway cutting across Nairobi National Park to the hundreds of thousands of refugees in the Dadaab refugee complex, from fashion shows and premieres in Nairobi to lions in open grassland and tribal festivals, and much much more. Below, in roughly chronological order, is a look at some of the stories brought to us through Yasuyoshi Chiba’s lens in the past year.

The surprise visit by President Donald Trump to military personnel in Iraq and Germany the day after Christmas was a particularly welcome development, given his previous departure from this time-honored tradition of his predecessors around the holiday season. The visits were marred, however, by the president’s overtly political rhetoric and by his encouragement of the small number of uniformed personnel who offered him their “Make America Great Again” hats to sign, or who displayed campaign banners. It’s the latest instance of the erosion of long-standing commitments to apolitical institutions—and the comparative indifference with which these acts were greeted ought to worry all of us.

Employees of the U.S. government, in general, face restrictions on the “political activity” in which they can engage in the workplace. Uniformed members of the U.S. military are arguably held to a high standard of nonpolitical behavior, even outside the workplace and particularly while in uniform. The presence of campaign paraphernalia at a presidential visit—and the president’s blithe disregard for protocol in choosing to sign some of that paraphernalia, to say nothing of his politically tinged speech to military personnel in a war zone—runs afoul of at least the spirit, if not the letter, of written rules such as Department of Defense Directive 1344.10 (Political Activities) and Uniform Code of Military Justice Article 88 (Contempt Toward Officials) and Article 134 (General Article).

These displays should never have been allowed, and the president certainly should not have encouraged them. But the real problem was not the boneheaded actions of a few men and women in uniform. They made a mistake in a moment of exuberance, excited to see their commander in chief. They may face a tongue lashing, or perhaps some minor discipline, but that is the most that should, and likely will, happen to them.

[Read: The president is visiting troops in Iraq. To what end?]

Nor is the real problem Trump himself. The president has made it clear that he has little interest in abiding by institutional customs and norms. Where the law does not explicitly and unequivocally prohibit behavior on his part, he construes that as an opportunity to engage in the behavior. He pays little regard to whether he should do so, or whether it would reflect poorly on the institution of the presidency itself. That is who the president has always been, and it is who he will remain.

No, the real problem is the political tribalism that continues to erode our apolitical institutions. Rules are rules, even when politically inconvenient. The military in particular is one of our most cherished apolitical institutions. We rely on the military to protect the country as a whole, regardless of which party controls the executive branch. The public needs to retain the assurance that military personnel are fighting for the United States of America, not merely for the current resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Maintaining that public confidence requires equal and just application of the rules, even on minor issues, such as what transpired in Iraq and Germany.

Democracy does not die in darkness—it dies with indifference. It was indifference that led some to excuse the president’s breaking decades of institutional custom in order to conceal his tax returns, or his refusal to divest from his businesses. It was indifference that led to the acceptance of the politically expedient erosion of anti-nepotism laws so that Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner could serve in the White House. And it was indifference that allowed the politicized micromanagement of the civil servants at the Justice Department conducting the Russia investigation.

[Eliot A. Cohen: Presidents need to visit the troops]

Now some of the president’s defenders are trying to persuade us to ignore erosion of the apolitical bubble we have so carefully constructed over the years around the civil service and the U.S. military. They suggest that only some rules really need to be worried about, and the rest are just for show—especially if we happen to like the political views being advanced by those who ignore them.

There is danger in indifference. Those who opposed the president’s agenda—and, even more so, those who support it—should see that danger clearly, and decline to take the bait.

The year was not a month old when a 16-year-old allegedly opened fire in a cafeteria in Italy, Texas, injuring one of his classmates on January 22nd. It was the first shooting on a K–12 campus this year. One day later, in Benton, Kentucky, a 15-year-old student allegedly killed two of his classmates and injured 17 others. Over the next three weeks, there were shootings at or near Lincoln High School in Philadelphia, Salvador Castro Middle School in Los Angeles, and Oxon Hill High School in Maryland. And on February 14, a former student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, allegedly killed 17 people and wounded more than a dozen others.

2018 has been indelibly marked by school shootings, and there was concern—at least at the outset—that it would be a year defined by a failure to address the problem, which several political figures, mostly Democrats, identified as access to guns. There had been hundreds of gun laws passed since a gunman killed 26 people, including elementary-school students, in Newtown, Connecticut, and most of them had expanded access to guns. But according to the Giffords Law Center, a gun-violence-prevention advocacy group, “the gun-safety movement experienced a tectonic shift in 2018.”

The law center tracked 1,628 firearm bills in 2018 and compiled a year-end review, which was released earlier this month. In total, 26 states and the District of Columbia enacted 67 new “gun safety” laws. “The growing number of mass shootings and domestic violence homicides, as well as the devastation wrought by guns in urban communities, has culminated in a surging pressure to address this epidemic,” the report reads.

The raft of legislation is significant not least because after so many years of school shootings, it had started to feel like every mass school shooting would be met with a familiar round of “thoughts and prayers” and calls for action, and then another school shooting would come, with little having changed. To be clear, school shootings remain rare, despite the devastating consistency with which they seem to occur. As of EdWeek’s latest tally, there were 24 school shootings with injuries or deaths this year—an average of two each month. But the very act of keeping count has its own complexities, and as my colleague Isabel Fattal wrote in February, “the messiness of counting school shootings often contributes to sensationalizing or oversimplifying a modern trend of mass violence in America.”

Parkland helped cut through the debate about numbers, putting a face and a voice to the violence. The students affected by the shooting took control of the conversation. “They have been through a trauma that would leave most adults curled in a prenatal pretzel under the bed,” Michelle Cottle wrote in The Atlantic. “But these teens have elbowed their way into one of this nation’s most vicious policy debates, demanding to have their say.” The students energized the efforts that had been laying the foundation to challenge gun laws since the Newtown shooting, and they helped plan a nationwide March for Our Lives, which included a massive rally in Washington, D.C. State legislators set to work rewriting laws. The Trump administration banned bump-stocks, an attachment that makes semi-automatic weapons fire faster. And according to an NPR analysis, gun-control groups outspent gun-rights advocacy groups during the 2018 campaign cycle; in previous cycles, spending by gun-rights groups far outpaced that of gun-control groups.

For activists, 2018 has offered reason for hope. “We are going to be the kids that you read about in textbooks,” Emma González, a Parkland student, said in a viral speech. “Just like Tinker v. Des Moines, we are going to change the law. That’s going to be Marjory Stoneman Douglas in that textbook, and it’s all going to be because of the tireless effort of the school board, the faculty members, and most importantly, the students.”

But as much as some things were changing, there were reminders of how firmly entrenched the shape of the gun debate is. For instance, Trump’s school-safety commission, formed in response to Parkland, said that it wouldn’t focus on guns. Earlier this month, it released its recommendations to “make schools safer.” The report downplayed the role of guns, emphasized mental-health services, focused on Obama-era school-discipline rules, and advocated “no notoriety” for school shooters. All told, the report signaled that even though the conversation has shifted somewhat, the changes are marginal, and for the most part the gun debate in America looks more or less the same.

The critical last layer of Donald Trump’s support in 2016 came from voters uncertain that he belonged in the White House. Now he appears determined to test how much chaos they will absorb before concluding they made the wrong decision.

For all the talk about the solidity of Trump’s base, it’s easy to forget how many voters expressed ambivalence even as they selected him over Hillary Clinton. Fully one-fourth of voters who backed Trump said they did not believe he had the temperament to succeed as president, according to an Election Day exit poll conducted by Edison Research. That number rose to about three in 10 among both the independents and the college-educated whites who backed Trump, according to previously unpublished data provided to me by Edison.

Yet even as they expressed hesitation about the future president, those voters were still willing to take a risk on him, either because they disliked Clinton or wanted change or preferred to disrupt the political system. Some may have thought Trump would moderate his behavior in office.

[Read: Republicans didn’t learn anything from the midterms]

It’s an understatement to say Trump has dashed those hopes. Instead, he has continued to shatter norms of presidential behavior in every possible direction. Allies and opponents alike usually attribute Trump’s volatility to personal factors: an impulsive and mercurial personality that lashes back at any perceived affront, seemingly without much thought about the long-term implications and with a reluctance to take advice or consider evidence.

But after two years, it’s also clear that Trump sees strategic value in violating presidential norms. He’s shown that he believes he benefits from immersing all of those around him in constant unpredictability. Probably even more important, he sees barreling through the informal guardrails that have constrained previous presidents as a way of signaling to his core supporters that he will go to any length to defend their interests. From that perspective, the more establishment voices condemn his behavior, the more he signals to his base that he’s fighting for them by any means necessary.

Until the midterm elections, it was common for Trump critics to lament that he paid little price for these excesses. But the November results showed, in a quantifiable way, that Trump’s belligerent and erratic behavior does carry a cost. Democrats won 40 seats in the House—and carried the national House popular vote by a larger margin than the GOP did in its 1994 or 2010 landslides—even though unemployment was below 4 percent and two-thirds of voters described the economy as either excellent or good. A performance that weak for the president’s party should not be possible with an economy that strong. But both independents and college-educated white voters, two groups that expressed widespread doubt about Trump’s temperament from the outset, broke solidly for Democrats last month after narrowly tilting toward him in 2016.

Rather than taking that shift as a sign to reconsider his course, Trump has doubled down on disorder since Election Day. He approaches the New Year engulfed in three distinct crises, all of which he ignited with his own actions.

Trump has precipitated a diplomatic crisis by abruptly announcing his intention to withdraw American forces from Syria. That triggered the resignation of Defense Secretary James Mattis, which reinforced the initial tremor over the sudden reversal with a powerful aftershock.

Trump has precipitated a governing crisis by forcing a partial federal shutdown through his demand for $5 billion in funding for his border wall—an ultimatum that the administration itself only a few days earlier acknowledged could not win 60 votes in the Senate.

And he’s instigated a financial-market crisis through the shutdown, his saber-rattling on trade with China, and his repeated Twitter attacks on Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell—with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin providing the aftershocks in this case through his amateurish efforts to calm the markets last weekend.

Trump defenders argue that, on the merits, he can win each of these fights politically (though that case seems very tenuous for the border wall, which has faced majority opposition in virtually every public poll conducted during his presidency). But the larger risk to Trump is that the virtues of each of his positions become indistinguishable amid such swelling levels of confrontation and instability; arguing for any individual policy in this environment may be like trying to identify a single wave in a flood tide.

[Read: The Trump administration’s lowest point yet]

Each of the current crises may recede in 2019, but the overall trajectory of Trump’s presidency points toward more, not less, disorder. Trump has systematically dismissed advisers such as Mattis who were considered, however imperfectly, the most powerful constraints on his behavior. And Trump will face new provocations that are likely to trigger his most belligerent impulses—especially from an incoming Democratic House majority that’s poised to investigate every aspect of his presidency (including his personal finances). Looming close behind are more potential indictments from Special Counsel Robert Mueller and the release of his final report on Trump, Russia, and the 2016 campaign. In 2019, combustion may be as great a risk to Trump as collusion.

As the stock market has nosedived in December, it’s become common for financial traders to tell business reporters that they now see concrete danger in Trump’s Twitter and press-conference tirades, which they once treated as only “background noise” behind policies that they generally supported.

But since their November losses, strikingly few congressional Republicans have echoed that verdict. Even amid the current maelstrom, very few have publicly broken with Trump over the shutdown or his attacks on the Fed. And while some have criticized his Syria decision and lamented Mattis’s departure, hardly any have acknowledged the broader concerns about Trump’s decision making and stability that both developments provoke.

The market meltdown in particular may be creating the most pressure Trump has yet felt to temper his behavior. But so long as congressional Republicans refuse to publicly demand change, the waves of chaos emanating from the Oval Office are likely to only grow higher. Through their deferential silence, Republicans are betting they can withstand those waves better in 2020 than they did in 2018.

The video Kevin Spacey posted on Christmas Eve has been repeatedly described as “bizarre,” with good reason: No one knows what it means. Wearing a Santa apron and occasionally sipping from a mug, Spacey seems to inhabit his House of Cards character, Frank Underwood, drawling things such as, “We’re not done, no matter what anyone says.” The monologue hints at a desire to return to Cards, despite his character having been killed off (“You never actually saw me die, did you?” he asks). It plays as commentary on the more than 30 allegations of sexual misconduct against Spacey: “You wouldn’t rush to judgment without facts, would you?” The confusion the video has sown may have distracted from the news that the actor was just charged with the sexual assault of an 18-year-old in 2016.

What’s clear, at the least, is that Spacey chose for his first significant reemergence to be a showcase—or “showcase,” heavy on the air quotes—of his acting. And for it to spotlight one of the roles that the public once feted him for. And for it to dispense thoughts about morality and truth. All of which makes a statement: Don’t separate this artist from his art.

As year two of the post–Harvey Weinstein reckoning unfolds, that old ethical question—can art be evaluated apart from its artist?—feels more and more academic. Whether or not they should, many people clearly are fine with being entertained by alleged abusers. The cheers outnumbered the walkouts at surprise comedy sets by the confessed creep Louis C.K. The rapper XXXtentacion faced well-publicized allegations of hateful violence, and yet since his death, his music has risen to mega-popularity. Art, it seems, can survive allegations. What’s more unnerving is the suspicion, now, that artists can weather them, too—by relying on the goodwill engendered by their work.

Spacey’s career long blended highbrow acclaim and mainstream appeal. A stage thespian before he was a film lead, he amassed glittering awards and a prestigious post as the artistic director of the Old Vic theater in London. These are not merely the spoils of a movie star; they are the signifiers of one who approaches his trade as capital-a Art. This particular artist’s muse? Evil. Spacey’s signature turns in The Usual Suspects, Seven, and House of Cards were all charismatic bad guys, and for 1999’s American Beauty, his suburban-dad character, Lester, lusted after a teenage girl. Accepting the Oscar for Best Actor, Spacey said he loved playing Lester “because we got to see all of his worst qualities and we still grew to love him. This movie to me is all about how any single act from any single person put out of context is damnable.”

The “Let Me Be Frank” video may be an attempt to reassert this professional history. Spacey the great actor is implied in his complaint that his scandals led to an “unsatisfying ending” that could have been “memorable”—a likely dig at the poorly reviewed final season of Cards that didn’t feature Frank Underwood. Spacey the philosopher of misdeeds is here, too: “I told you my deepest, darkest secrets,” he says, seeming to speak both as Frank and also as himself, the public figure. “I showed you exactly what people are capable of. I shocked you with my honesty, but mostly I challenged you and made you think. And you trusted me, even though you knew you shouldn’t.”

[Read: The Kevin Spacey allegations, through the lens of power]

Left unstated is the way that Spacey’s acting career was accompanied by allegations of misbehavior, sexual and otherwise. (He’s apologized to his first public accuser, Anthony Rapp, and denied or remained silent on other allegations.) The Usual Suspects shut down production for two days after Spacey made an advance on a younger actor on set, the actor Gabriel Byrne told The Sunday Times. Producers on House of Cards conducted an investigation and sent Spacey to retraining in 2012 after an inappropriate “remark and gesture.”

Also left unreckoned with in Spacey’s video is the difference between the thrill of fictional villainy and the effects of the real-life kind. One of Spacey’s accusers, the filmmaker Tony Montana, has talked about the PTSD and shame he suffered after Spacey allegedly grabbed him. Another, who says he was 15 when a 24-year-old Spacey tried to rape him, told Vulture, “What he left me with, more than what he took from me, was a sense that I deserved this. And that’s the knot I’m still untangling.”

All of this queasy context is surely part of why Spacey’s video accrued more than 7 million views in just a few days. People are rubbernecking at the disgraced star opting to play the villain. “Kevin Spacey is sending a very disturbing message as he chastises his audience,” the actress Ellen Barkin tweeted. “If you hypocrites loved me as a murderer, why won’t you love me as a sex offender? Maybe because Frank Underwood’s crimes are fiction and Kevin Spacey’s are not.” Wrote Patricia Arquette, “I’m sure none of the men who were kids at the time of their sexual assaults appreciate @KevinSpacey’s weird video.”

But another unsettling fact is that some portion of the video’s viewers really do miss Spacey on-screen—and would cheer his return to public life, regardless of whether he’s an abuser. The YouTube clip has more than 51,000 “dislikes” and 170,000 “likes”: an imprecise and manipulable metric of public sentiment, yes, but one that’s reflected in some of the comments. One example: “Kevin Spacey is brilliant at what he does and what he does makes millions of people happy. The truth is we all never heard his side of the story.” The Daily Mail’s Tom Leonard reports on rumors of a comeback plan for Spacey and points out that there’s a website of unknown provenance, supportkevinspacey.com, where fans can leave encouragement. It appears that some have written in to applaud “Let Me Be Frank.”

Netflix has not commented on the video, but it seems unfathomable that Spacey’s stunt actually teases a return on House of Cards, whose recent season was advertised as its last. (The company reportedly lost $39 million after ending its relationship with the actor.) With authorities in New England filing charges and other investigations of Spacey reportedly under way in Los Angeles and London, the likelihood of a career reboot seems even more ludicrous. The quality of this video itself—the home-software title font, the bad imitation-Cards dialogue, Spacey’s conspicuous failure to act as though there’s any coffee in his mug—adds to the sense of him as delusional. But at the core of this gambit may be the belief that a man like him can act his way out of anything. Given how many guys accused of #MeToo–related offenses seem to be doing okay, is that so farfetched?

Early every Sunday growing up in Australia, Anne Gu attended Chinese school, the weekend classes where many children of Chinese immigrants learn Mandarin. There, she bonded with her classmates over their shared sense of obligation. “We understood we had to be there because of our culture, our parents,” Gu told us, “while our other friends were sleeping in.”

They kept in touch via group chat, exchanging jokes about life as first-generation Asian Australians. “Someone was like, it would be fun if we made a Facebook group, and we all agreed,” Gu said. In September, she and her friends created a group and added “all the Asian friends” on their Facebook friend lists. They called it Subtle Asian Traits, after a then-popular Facebook group among Aussie teens called Subtle Private School Traits.

The high-school seniors had intended it to be a small community of friends from the Melbourne area, so when its member list ballooned to 1,000 people, “I was like, no way,” Gu said. Three months later, the group is among the most popular on Facebook, with more than a million members from around the world at the time of reporting, and more every day. “This group is the reason I go on Facebook like 10 times a day now,” one member wrote in it. The group skews young, and popular posts invoke the quotidian relatability of grabbing bubble tea with friends and enduring strict parents—or dealing with ignorance.

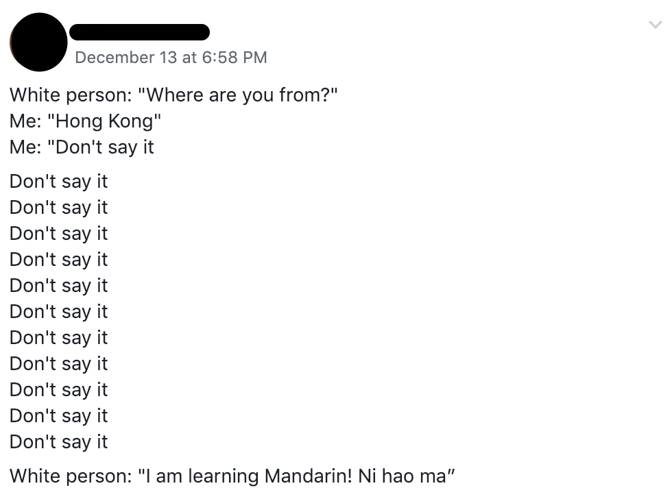

One popular meme in the group riffs on something dreaded by many diasporic Asians—the “Where are you really from?” line of questioning:

(The primary language in Hong Kong is Cantonese, not Mandarin.) For many in the group, it’s an all-too-familiar microaggression.

The group has become a place for diasporic Asians to talk about encounters like this, despite being scattered across the globe, many in neighborhoods without a lot of people who look like them. “Subtle Asian Traits demonstrates another example of the importance of specificity and universality. To reach the most people, you have to be incredibly specific,” says Takeo Rivera, a professor at Boston University who researches Asian American cultural production.

Subtle Asian Traits has now inspired at least 40 other groups, according to Subtle Asian Yellow Pages (itself another Facebook group): Subtle Asian Dating (for more than 275,000 Asian singles), Subtle Asian Dating: Wholesome Edition (newly created, for more than 100 Asian “wholesome” singles), Subtle Asian Christian Traits (for more than 63,000 Asian Christians), Subtle Asian Pets (for more than 22,000 fans of corgis and more), Decolonized Subtle Asian Traits (“for the AAPI who want less boba and more SJW with their memes”), and more.

The past year has shown a visible hunger among the Asian diaspora for cultural purchase: Look at the success of Crazy Rich Asians, the hype over the international rise of K-pop, and the clamor for literature by Asian authors. But media visibility for Asians remains lacking in many respects. In the United States, according to statistics compiled by scholars at six different California universities, only 4 percent of series regulars on TV last year were Asian American and Pacific Islanders—and more than half of those shows were canceled that year. “Asians haven’t had the opportunity to have their voice heard in media. We’re underrepresented,” Gu said to us. “Our Facebook group is giving so many Asians an opportunity to voice their thoughts.”

The Facebook group is a digital manifestation of a “third space,” or the in-between space in which “cultural hybrids,” such as the children of immigrants, adrift between two national communities, shape their unique identities. It’s fitting that the group’s founders met at Chinese school, another third space.

“We have to sort of bounce between both cultures in our lives,” Gu said. “I feel like the group has helped people come to terms with it, and know they’re not alone, and that there are so many people around the world who have the same struggles and same experiences.” Subtle Asian Traits has revealed the breadth of the diaspora. While most of the members in the group are Asian Australians and Asian Americans, reflecting the large proportions of Asians in both countries, other members hail from countries such as Sweden and Switzerland—“which I hadn’t even known had that many Asians,” Gu marveled. “And we can still laugh and agree on the same memes.”

One prolific poster in the group, Laura Ngo, grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts, and didn’t have many Asian friends at school, with the exception of those she met at the Vietnamese church. So she found them online. “I feel like it’s reconnecting a lot of Asian Americans with people from their communities, and it’s like one big group of understanding—all these jokes that you don’t have to explain,” Ngo says.

The surge of these groups speak to a “need and yearning for a safe space—where Asian Americans can express our authentic selves,” explains Jenn Fang, the founder of reappropriate.co, a blog on Asian American feminism and race. Subtle Asian Traits is the latest iteration in a long line of online Asian communities, like Yellow Board and Rice Bowl, popular message boards from the early 2000s, or Asian Avenue, an early social-networking site for Asian Americans. Fang, a message-board alum, joined Subtle Asian Traits after hearing about it from us.

The group, like many other Facebook groups centered on shared experiences, has a therapeutic function. Some of its content references cultural pressures that many immigrant children face. “Any other not-skinny/not-small Asian folks out there who struggle with body image shit? Especially as a Korean ... every time I go back to Seoul, I feel this crippling insecurity, like by not being thin I’m a disgrace to my culture,” one discussion post reads, with thousands of sympathetic responses. “My father almost flipped a shit and started yelling at my brother when he didn’t get into Columbia,” another popular post reads. “I know that immigrant parents go through so much to set themselves up in a new country. I really know that my parents struggled. But what do you guys think is fair for the kids or not?”

[ Read: Facebook groups as therapy ]

Other posts retain the cavalier tone of memes, but hint at trauma. A poll asking, “What did your parents beat you with? Lol” received thousands of responses as well. The choices: belt, back scratcher, sandals, fly swatter, and shoehorn. (Belt won.)

There is a tension inherent in Subtle Asian Traits’ attempt to place diverse experiences under one “Asian” umbrella. Some worry that its posts can perpetuate stereotypes about tiger parents and model minorities. Others have accused it of excluding content about South Asians, despite billing itself as a space for everyone. There are the usual problems with trolls that surface in any corner of the internet, too.

Alisha Vavilakolanu, a 21-year-old psychology student, notes that “people were using slurs against South Asian people [in the group],” but the moderators didn’t intervene until, she feels, it was too late. She looked up the group’s moderators and found no South Asian representation. “It’s important to have people on the other end who can recognize [abusive behavior] and immediately be like, ‘That’s not okay, we don’t accept that.’” The concern about its lack of representation of South Asians helped in part to spur the creation of yet another meme group: Subtle Curry Traits, which features more South Asian–focused content, though it has fewer members (about 223,000 at the time of reporting).

When we shared criticism of the group’s low South Asian visibility with Gu, she said, “It’s a very big group, so it’s very hard to control what gets posted and what’s not. We try to be as inclusive as possible. At the end of the day, there are more East Asians in the group than Indians.” Gu and the 14 other administrators and moderators spend hours reviewing the more than 4,000 daily submitted posts as if working “a full-time job,” as Gu put it. When they come across offensive posts, they screenshot them and discuss what to do over a group chat. The teenagers have become gatekeepers of cultural production, holding the power to shape norms—including the sticky question of what is “Asian” enough to be posted in the group.

They’re also getting many requests about monetizing the group. Indeed, the administrators have started posting sponsored content for an Australian mattress company promising a bed so firm “your bubble tea won’t spill no matter how many you’re drinking.” According to Gu, the money will go toward covering expenses to “protect our online [identities].”

But the teens, who are currently on break for the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, are still trying to focus on their original goals for Subtle Asian Traits. “We labeled the group [Facebook category] as ‘family,’ so that’s what the group’s purpose is, to allow people to feel like they all belong to something,” she said, alluding, like nearly everyone we spoke with, to the loneliness of being a diasporic Asian, fitting in neither here nor there. Perhaps the explosion of this Facebook community was inevitable: People want to find their people.

Some enterprising group members have taken it upon themselves to move its conversations offline. Hella Chen, the co-founder of Subtle Asian Dating, told us, “There was a need for this in the community that would allow for a better way for people to connect with others. Dating was the thing in the sense that people wanted to get to know someone personally.” And at least based on some posts in the group, members have been able to find love with fellow Asians.

[ Read: When internet memes infiltrate the physical world ]

Matt Law, a 27-year-old entrepreneur, organized a Subtle Asian Traits meet-up in New York City that attracted more than 400 people—and he plans to host more. “In the beginning it was like a joke, to see if people were interested or not, and in the end, people ended up being very receptive,” he says. “It’s a great way to bridge community and have people meet up in person and not just talk through the Facebook group.” Group members are organizing meet-ups in Vancouver; Toronto; Boston; Washington, D.C.; and other cities.

And Gu, for her part, bonded with her own family over the group. When she saw a post about a traditional Chinese dish made of scrambled eggs and tomatoes—a simple comfort food she’d forgotten about—she asked her parents to make it for dinner. “I was like, I haven’t had this in ages, and my parents were like, ‘Okay, we’ll make it for you.’” Her parents had forgotten about the dish, too. It was a moment of connection between generations, one made especially potent by the prevalence of the group’s themes of intergenerational alienation. “And then my dad made it again like the week after.”

Children should have equal access to a high-quality education. It’s a popular talking point among both the left and the right because it’s non-objectionable—yet it’s far from the reality of American primary and secondary education. As the landmark Reagan-administration report, A Nation at Risk, put it 35 years ago, “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.”

Advocates for so-called school choice, however, argue that they have a solution: If you provide students and families with a broad range of options—including charter schools, private schools, and traditional public schools—they can choose the one that best suits them. In theory, the schools would compete with one another, vying for students, and the competition itself would spur them all to improve, as Peter Bergman, a professor of economics and education at Columbia University, told me. Ideally, that competition is open to all students equally, as it is that sort of open free-for-all that ought to produce the best results.

[Read: Public opinion shifts in favor of school choice]

Of course, for this to work, parents need to know about the options available to them. Research has shown that there are significant barriers to choice, among them access to transportation, enrollment issues, and a lack of information about the schools. A new working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research adds another dimension to this problem: Schools themselves may play a role in encouraging more “desirable” students to enroll, meaning that often it’s more the schools choosing the students than the reverse.

The study, authored by Bergman and Isaac McFarlin, a professor of education at the University of Florida, examines the beginning of the school-choice process: inquiries about how to apply. In a randomized test, the researchers sent emails from fictitious parents to more than 6,000 charters and traditional public schools in areas with school choice. “Each email,” Bergman and McFarlin wrote, “signaled one of the following randomly-assigned attributes about the student: their disability status, poor behavior, high or low prior academic achievement, or no indication of these characteristics.” The pair wanted to see whether schools provided the same information to all parents, regardless of any difficulties alluded to in the emails.

Ultimately, Bergman told me, they found that the schools they emailed are less likely to respond to students who are perceived as “harder to educate.” The charter schools, he added, were “particularly less likely to respond to students with a particular [individualized educational plan]”—meaning students who have a special need that would require them to be taught in a separate classroom. This “cream-skimming,” or providing information only to high-value students, is a “key source of potential inequality,” Bergman said.

[Read: How to rile up education debates with one word]

An easy takeaway from the report, McFarlin told me, would be that “charter schools discriminate against special-needs kids,” but that would be an incomplete assessment, since the schools they emailed replied to the parents of any student with any disadvantage—behavioral issues, low grades, or special needs—at similar rates. Now that researchers know whether schools responded to the emails, the next step is digging into the responses to see if they are actively discouraging certain students from applying.

In the meantime, Bergman and McFarlin hope that this sparks a conversation about how the subtle discrimination of not responding to an email can create an information gap for families in the application process. School choice, with a goal of equitable access, could work, they say, but only if it truly allows the students to choose schools, rather than allowing the schools to choose students.

Over the next month, The Atlantic’s “And, Scene” series will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy moment. Next up is Debra Granik’s Leave No Trace. (Read our previous entries here.)

The most impressive thing about Leave No Trace is that the enemy of the film is not the government. Yes, Debra Granik’s story is about a father, Will (Ben Foster), and his daughter, Tom (Thomasin McKenzie), trying to live away from society, and the way that their dreams are shattered when they’re arrested for trespassing on public land. Will, a traumatized Iraq War veteran, craves isolation and peace above all else, and he chafes at almost any kind of institutional structure. So when he’s taken away from the forest, separated from his daughter, and hauled in front of social services, the whole process should feel monstrous. Somehow, it doesn’t.

Granik is a filmmaker with an incredible gift for conveying characterization cleanly and simply; her camera doesn’t judge, but rather empathizes. It’s likely obvious to the viewer, early on, that Will’s hope for a quiet life off the grid is bound to fail, especially as his daughter grows older and begins seeking a life of her own. It’s equally obvious that Will is going to ignore the orders of the state of Oregon the first chance he gets, even if he’s threatened with imprisonment. Still, soon after he and Tom are taken out of the forest, Granik digs into the specifics of the government’s intervention and the ways in which officials are trying to help. In fully considering the situation from multiple angles, she gives a careful portrait of its intractability.

[Read: ‘Leave No Trace’ is a shattering, essential drama]

Once Will is processed, he’s assessed by a social worker named James (Michael J. Prosser), who sits him in front of a computer and has Will take a personality test of sorts. “Respond true/false to each question … There’s 435 questions. If you can’t answer something, you’ve got three seconds, it’ll beep and move on to the next statement,” he explains soothingly, before turning the computer on and departing the room. The test is somewhat less soothing, featuring a halting, robotic voice that utters true-or-false statements like “I enjoy reading articles on crime” and “I have nightmares or troubling dreams.”

Will keeps up at first, but the statements grow more probing and accusatory, even as they’re delivered with the same flatness. “I think about things that are too bad to talk about.” “Things aren’t turning out like the prophets said they would.” “It seems like no one understands me.” Will’s grumpy demeanor quickly crumbles into anguished confusion; Foster, doing career-best work, expresses all of Will’s horror and despair at what he’s being asked with a single mournful stare. He’s someone trying to live a meaningfully detached life; the test’s assumption is, of course, that he’s crazy, angry, or both.

As Will ignores the questions, James comes back in to console him. “You wouldn’t be the first one to have a problem with this test,” the social worker confesses. James is as warm and sympathetic as he can be, but he’s still there to do a job, and the test is what it is—a fruitless, reductive attempt to glean why someone might not want to be part of society. The sequence plays out in an office decorated with forest wallpaper, a facsimile of the environment Will and Tom were just plucked from; it reads like yet another effort to offer comfort while reasserting control.

James and the other social-service workers do their best to find Will and Tom a placement with a rural family that might approximate their old life off the radar, while also keeping them on Oregon’s books. If this entire early section of the film played out malevolently, the rest of Leave No Trace (which sees an increasingly frayed Will taking Tom back into the woods to try and reclaim their former life) wouldn’t work; it’d feel too righteous and pure. Instead, all the tricky ideas Granik wants to explore are laid out from the start, so that the later acts can wrestle with them. The world that Will is trying to escape isn’t evil, but even at its most benevolent, it has no real understanding of how to handle people like him, and vice versa. Thanks to Granik’s sensitivity, Leave No Trace is a humane attempt to grapple with that alienation.

Previously: Hereditary

Next Up: Mission: Impossible – Fallout

What are the aliens thinking? That’s always been a problem for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). Until recently, SETI’s focus has been on alien “beacons,” signals that somebody somewhere intentionally beamed into space. But this traditional method involves making informed guesses about what the aliens were thinking when they built their beacons, and those guesses may turn out to be laughably wrong.

There’s an entirely new way to do SETI now, and understanding its promise begins with considering the properties of solar panels. Rather than just looking for beacons, SETI researchers now want to also search for unintentional “technosignatures” from alien industrial civilizations. An example of an unintentional technosignature could be pollutants in a distant planet’s atmosphere, or the shadow of a large artificial structure orbiting a planet.

[Read: Searching the skies for alien laser beams]

The best way to find a technosignature is to search for the observable byproducts of activities that are necessary for all civilizations. For instance, industrial civilizations, by their very nature, must extract energy from their surroundings to do work and keep themselves running. In a creative paper published last year, the astronomers Manasvi Lingam and Avi Loeb wondered what technosignatures would radiate out from a civilization that powered its world by harvesting solar energy on a planetary scale.

It’s easy to imagine a civilization covering a fraction of its world with solar panels. This is something we might try in, say, the Sahara desert. What Lingam and Loeb did was calculate how the large-scale deployment of solar technology would leave a mark in light that bounces off a planet’s surface.

Technosignatures are similar to biosignatures, which are the means for finding life of any kind on a planet. The chemical makeup of an exoplanet’s atmosphere can, for example, be extracted by catching light passing through the planet’s veil of gas. On Earth, atmospheric oxygen or methane would quickly react away without our planet’s abundant life. That means seeing oxygen and methane in an exoplanet atmosphere might serve as a good signature for a biosphere thriving on that distant world.

But the vegetation covering our planet creates many kinds of signatures that could be seen from a distance. In particular, Earth’s vast array of leaves alters the spectrum of sunlight that we reflect back into space. Chlorophyll, the chemical responsible for photosynthesis, strongly absorbs light in the green part of the sun’s spectrum while strongly reflecting its red light. That means that sunlight bouncing off Earth has a noticeable “red edge” from all the biosphere’s leaves, grass, etc. If you plotted how much sunlight gets reflected from Earth versus that light’s wavelength, you’d see the planet’s “reflectance” rise sharply as you cross from the green parts to the red parts of the spectrum. The rise is so sharp that astrobiologists have long floated proposals aimed at searching for a photosynthetic red edge from exoplanets. They’ve even calculated the reflecting properties of novel forms of photosynthesis that might evolve on worlds with stars very different from our sun.

[Read: Congress is quietly nudging NASA to look for aliens]

Lingam and Loeb saw that large-scale deployments of solar-energy collectors would also change the way sunlight reflects from an exoplanet. Focusing on the properties of silicon, they calculated the wavelengths of light that solar panels would absorb and the wavelengths that they’d bounce back into space. Instead of a red edge, their calculations showed that silicon-based solar panels would produce a sharp change in reflectance at the ultraviolet part of the electromagnetic spectrum. They called this the silicon edge.

A skeptic might argue that silicon is too human-centric a solar-panel construction material to produce a universal technosignature. Lingam and Loeb, however, gave convincing arguments that it’s the element of choice for solar-powered exocivilizations. There are only a few kinds of light-energy harvesting materials you’d find on any planet. Using the cosmic abundances of the elements, Lingam and Loeb showed that most planets are likely to have a lot of silicon lying around, making it an obvious component for building solar collectors.

For good measure, the two scientists also calculated the reflectance properties of gallium arsenide and the mineral perovskite, both of which might be used in solar panels. Each produced its own distinctive edge in the planet’s spectrum. Now, all astronomers have to do is go looking for these signatures. Fortunately, the telescopes they need to do so are starting to come online.

Gabe Kenworthy, a 22-year-old freelance content manager for some of Instagram’s most notorious meme pages, was up at 2 o’clock on Christmas morning. He was sitting on his parents’ couch searching for heartwarming holiday content to post when he realized something was wrong.

Just after he sent his partner some memes for approval, Kenworthy’s phone exploded with texts. Jonathan Foley, the owner of a network of meme pages with millions of followers, including @SocietyFeelings, @Deep, and @Positivity, told him that Instagram had shut down his accounts without warning, along with a slew of others.

Instagram regularly purges batches of accounts that the platform says violate its terms. And this is not the first time Instagram has cracked down on spam during the holidays. In December 2014, the company deleted hundreds of thousands of accounts in what became known as the “Instagram rapture.” But rarely does a strike affect so many notable pages at once. Some memers have estimated that more than 500 accounts were shut down over the past few days, including pages with millions of followers, such as @ComedySlam and @Pubity. Even @God was suspended on Christmas. “Instagram is the Grinch this year,” said Ryan, a 20-year-old who lost a network of pages with more than 1 million followers and asked to be referred to by his first name only because of concerns about hacking.

“We’ve seen behavior on Instagram whereby some usernames … are stolen or traded,” an Instagram spokesperson said in a statement on Tuesday. “We do not allow people to buy, sell, or trade aspects of their account, including usernames. We are consistently taking steps to disincentivize and stop this behavior, including removing accounts that violate our policies.”

[Read: How hackers are stealing high-profile Instagram accounts]

What frustrated many memers most about the mass ban was that they had no recourse and no way to learn more about their situation. Dylan White, a 21-year-old who ran @Jaw, a popular account that posted memes and pop-culture news along with photos of men who had strong jawlines, said he had been running his account for three years and had never had a problem with it previously. “This is my full-time income, so it’s very detrimental to my livelihood,” he said. Ryan was also worried about the money he lost in the crackdown. “I was trying to eat dinner and socialize with my family,” he said, “but knowing behind the scenes everything I’ve built, my entire net worth, was just gone before my eyes.”

Several memers who were also affected said that they hadn’t obtained their accounts improperly, though they could be taking the fall for bad action by previous owners. Some users, including Ryan, also had personal pages and accounts banned, ones that they knew they had founded from the get-go.

Theories circulated throughout the day on Kik, where owners of the largest meme pages on Instagram communicate. Some suspected that Instagram was cracking down on a rogue employee who had illegitimately claimed these usernames using an internal dashboard years ago and then sold them. In screenshots of Kik chats reviewed by The Atlantic, some people also wondered whether the purge was somehow tied to people’s devices, since Instagram has been known to punish spammers by deleting all the accounts associated with a specific device or IP address. Another theory was that Instagram accounts that switched too frequently between public and private were targeted, a tactic that large pages had been exploiting as a growth hack in recent months.

Second ban wave lads and that’s how you lose $300K worth of IG’s 😘🤦🏻♂️

— Ry (@Verdict) December 25, 2018Most meme account holders will likely never receive a detailed answer on what, exactly, they did wrong, but bans such as this serve as a powerful reminder of just how volatile and unregulated the Instagram meme industry is, and how little it’s tended to by the platform itself. Ben Cohen, the entrepreneur behind @BasicBitch, who has since sold off his large Instagram accounts, said that despite the vast amounts of money some meme accounts generate, they’re subject to almost no oversight.

Some popular memers, such as @TheFatJewish’s Josh Ostrowsky and @FuckJerry’s Elliot Tebele, have successfully tied their real-life personas to their Instagram handles, but most large meme accounts operate anonymously. In fact, it’s that very anonymity that allows these pages to transform themselves into a brand. Barak Shragai, the co-owner of @Daquan, told The Atlantic earlier this year that he considers Daquan’s anonymity a key advantage to the growth of his page, which has more than 11 million followers. Shragai says it allows followers to project their own personality onto the page and prevents followers from reading a meme through a particular lens based on who posted it.

[Read: Reddit’s case for anonymity on the internet]

But the disorganized, sometimes scammy way some meme pages do business, coupled with the fact that the main account holder is often obscured, makes dealing with them a unique challenge for Instagram. On the one hand, the platform relies on large pages and meme accounts for growth. On the other, it has a responsibility to protect its users from spam. Networks such as Twitter and Tumblr have previously taken an approach similar to Instagram’s Christmas campaign: mass-banning anyone remotely affiliated with terms-of-service violations.

Waking up on Christmas to half your instagram banned. Thanks Facebook Merry Christmas!!

—Mitchell Conran (@Narnoc) December 25, 2018The unfortunate consequence of this type of approach is not just that some innocent account holders unjustly lose their primary source of income, but also that an entire class of accounts that generate massive engagement are ignored and deprioritized. Since Vine’s public fall, platforms have begun to recognize how critical influencers are to their networks. YouTube has had a robust creator-relations team. Snapchat was forced to recognize the power of influencers after initially dismissing them. And Instagram has made a heavy push in the influencer space, courting big social-media stars at events such as VidCon and BeautyCon. Yet meme accounts, some of which have larger and more engaged followings than certain traditional social-media stars, remain largely ignored.

The Christmas meme purge has only exacerbated the relationship between Instagram and these types of accounts. One group of memers who are adamant that they never engaged in any type of banned behavior plans to press the company to establish a representative to field requests from the most successful creators. The move wouldn’t be unprecedented. Instagram and Facebook have a large internal team that deals with requests from publishers; if anything, pages such as @SocietyFeelings or @Jaw have more in common with some modern media companies and influencers than with average users. BuzzFeed, for instance, has scaled its main Instagram account to more than 4.4 million followers by posting memes and screenshots of tweets.

“We are our own BuzzFeed,” said Declan Mortimer, a 16-year-old who ran the @ComedySlam account, with more than 11 million followers. Kaamil Lakhani and Jonathan Foley, who work together on @SocietyFeelings, said they were even in the process of building a dedicated website, as accounts such as @Daquan have already done.

“It seems like Insta values celebrities more than anyone else,” said Mitchell Burke, a 17-year-old who lost several pages in the purge. “If you’re a content account, you’re treated as an average user. You could have 10 times the following as these celebs and still get treated like an average person.”

Damn IG really banned kiddo … the audacity

—Luca (@Lucainho) December 25, 2018Swish Goswami, a 21-year-old entrepreneur, lost @Swish, a basketball-themed news and meme account, and @JumpMan, a sneaker-themed account. He said that at the very least, Instagram should offer support for pages with more than 1 million followers and offer a dedicated person to “look at captions, tell us how to license content properly, how to credit it, how to manage copyright. Questions like these are not ones people should have with bigger pages.”

Despite the Christmas setback, most meme account holders mentioned in this article said that they weren’t planning to abandon the platform anytime soon. But the incident served as an acute reminder of how quickly they can lose it all and be forced to start from scratch. “We’re playing on rented property,” said Goswami, “and that’s just so apparent now more than ever before.”

When fans of My Brilliant Friend have finished the first season of HBO’s acclaimed television adaptation, they may find themselves looking to fill a void. The eight-episode series, which aired its finale earlier this month, followed the lives of Lenù and Lila, two girls growing up in a poor neighborhood in Naples in the mid-20th century. Their thorny, intense friendship—which Elena Ferrante’s wildly popular Neapolitan novels chronicle in intricate detail over the duo’s lifetime—has been fascinating to witness on the small screen. But until Season 2 arrives, viewers might consider passing the time with another acclaimed epic offering a simultaneously intimate and sweeping view of postwar Italy: the 2003 film The Best of Youth (or, La Meglio Gioventù).

When a recent Guardian article about HBO’s My Brilliant Friend noted that “this is a prestige Italian production, assembling the great and the good of the country’s cinema and TV,” the author could have easily been talking about The Best of Youth. Originally envisioned as a TV miniseries, the two-part, six-hour film directed by Marco Tullio Giordana follows two Italian brothers over the course of decades as they find their place within their country’s charged political landscape after World War II. Written by Sandro Petraglia and Stefano Rulli, the movie won the Un Certain Regard prize at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival and was even given a limited U.S. theater run. While some American viewers may have been put off by its length and subtitles, critics were nearly unanimous in their praise for The Best of Youth. A review in Slate said that the film, despite its length, “doesn’t have a boring millisecond.” Roger Ebert described the movie glowingly as a “novel” that made him feel as though he had “dropped outside of time.”

Both My Brilliant Friend and The Best of Youth succeed partly because they give viewers ample time to get to know and care for the characters, especially the central duos. My Brilliant Friend, with its stark, stage-set–like backdrops, drab colors, and characters who speak in dialect, feels like a window into an entirely different era and world. Meanwhile, the brightness of The Best of Youth, and the ease with which the actors—some already well known in Italy—inhabit their roles, holds the audience especially close over the considerable run time, making viewers feel as though they could be watching a home movie of their own family. Though the two works touch on similar political tensions and take expansive views of their protagonists’ lives during a certain period in Italian history, they diverge in tone and examine different slices of society. In many ways, The Best of Youth can be seen as both a cinematic complement and an antidote to the grimness and claustrophobia of My Brilliant Friend.

[Read: The gorgeous savagery of ‘My Brilliant Friend’]

That’s not to say the film shies away from tragedy: The Best of Youth introduces Nicola (Luigi Lo Cascio) and Matteo (Alessio Boni), two college-age brothers with very different personalities. The sociable Nicola boasts a lighthearted demeanor that masks a profound empathy, while the sullen, withdrawn Matteo struggles with anger issues—today, he might be diagnosed with clinical depression. In the mid-1960s, the movie makes clear, Italians with any kind of mental illness were often relegated to asylums or treated with electroshock therapy. Within the first 15 minutes of The Best of Youth, the brothers meet one such patient: a young woman named Giorgia (Jasmine Trinca), whom they decide to help. Their plan to smuggle her out of an institution and back to her family fails because, in their naïveté, they don’t stop to think that her family may have put her there in the first place.

This incident, which inspires Nicola to become a psychiatrist, is but one allusion to the larger societal changes that took place in postwar Italy. In addition to a reform of the psychiatric system, the film also tracks a rise in left-wing terrorism, and the Mafia killings and subsequent trials that would shake the southern part of the country in the 1980s. Both brothers become tangled up in these historical events, but their participation seems optional in a way that Lenù and Lila’s involvement in the ugliness of the era does not. In HBO’s My Brilliant Friend, which is also set in the latter half of the 20th century, the heroines are regularly threatened with violence, starting when they’re children, in their own neighborhood in southern Italy. Later, a teenage Lila realizes with horror just how much of their life is controlled by the Camorra, the Neapolitan Mafia.

Lenù and Lila can hardly be faulted for responding with a passive rage when faced with the limitations of their era, a time when women like them were expected to do little more than bear children to often abusive husbands. In its own way, this rage informs the girls’ fascinating, volatile relationship with each other. Their friendship is one that seems to fuel every manner of emotion—jealousy, fear, desperation, desire, and affection—as the girls work to envision a better future for themselves. The onscreen version of Lenù and Lila’s Naples feels closed off and Fellini-esque, with surreal backdrops and grotesque characters such as the lovelorn Melina and the predatory Donato. Just like the tunnel that separates the girls from the rest of the city, their poverty cuts them off from the outside world, also keeping their parents from imagining a different life for themselves or their children.

In contrast, Matteo and Nicola are both well educated and championed by their family from the start; the young men are aware of their relative privilege and of how society will define them by it. Their disappointment over the failed kidnapping of Giorgia sends them careening in different directions after they abandon plans to take a post-graduation trip together through Europe. Nicola gets as far as Norway’s Arctic Circle, while Matteo, praised as a brilliant literature student, leaves academics to enlist in the army. A few months later, the brothers reunite in Florence in November of 1966, during the flooding of the Arno River. They join the legions of volunteers who had come to rescue Florence’s priceless works of art, and who would come to be known as angeli del fango or “angels of the mud.” For many young people, this event would be their first taste of a lifetime of activism, and The Best of Youth is at its most relevant when it traces the brothers’ path toward that future.

As Matteo and Nicola grow older, the film depicts how the hopes of their generation—literally “the best of youth,” as in the title, taken from a Pier Paolo Pasolini poem—played out on both political and personal levels. The movie’s explicit examination of class privilege and responsibility will be familiar to many Italians who came of age in the postwar decades. Marco Cupolo, an associate professor at the University of Hartford, discusses this debate in his essay on The Best of Youth: “Would authenticity and unselfishness of emerging, well-educated classes lead the reforms of Italian institutions and society? What kind of moral values were young Italians looking for during the 1960s and 1970s?”

These questions call to mind a discussion that Lenù and Lila have with their peers in My Brilliant Friend’s fourth episode (“Dissolving Margins”) about whether to abandon their parents’ old rivalries in favor of neighborhood unity. “Our fathers did bad things,” says Lenù, as they discuss whether to accept a party invitation from the son of Don Achille, the feared neighborhood loan shark, “but we, their children, should be different.” Though the teenagers couldn’t have known it, their debate mirrored the social pressures that young people were confronting all across Italy.

Some young Italians concluded that their best chance at success was to leave the country altogether, an approach addressed in The Best of Youth as well as by Ferrante, who titled the third book in her Neapolitan series Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, as if to underscore how much geography defines her characters’ identities. But The Best of Youth shows how saving a generation can mean pointing it toward an exit: Early in the movie, a professor advises Nicola, “Do you have any ambition? Then leave Italy while you can. Italy is a country destroyed, a beautiful but useless place … with dinosaurs in charge.” Giancarlo Lombardi, a professor at the College of Staten Island CUNY Graduate Center, spoke about this powerful conflict—whether to leave or stay—among the youth of that period. “Some parties and leaders see us as not having had the guts to fight for our country,” Lombardi told me of his generation. “But this whole idea of the best of youth—what does it mean? At the heart of the show is the question of courage and the importance of rolling up your sleeves and making things better.”

In the end, this is really what draws the two brothers together, and what sustains their story— and viewers—over The Best of Youth’s six hours. As a soldier who will become a police detective and a left-wing student who will become a doctor, respectively, Matteo and Nicola continue to find themselves on different sides of an ideological divide. The two meet up again during a 1968 student riot in Turin, for example, where Nicola attends medical school. In a heated exchange about the violence taking place on their streets, Nicola’s radical girlfriend, Giulia, claims that they fight for the poor, while Matteo says, of a police colleague who was attacked by protesters and left disabled, “he is poor in a way you will never understand.” Yet somehow, in spite of arguments like this one, the brothers’ deep affection for each other and sincere desire to make their country better—even if they disagree about how—are the keys to their appeal. The audience comes to see each brother through the other’s eyes, to understand how great political disagreements can be reduced to mere squabbles in the face of filial love.

This kind of deep bond—one that manifests either as antagonism or affection—also anchors the Neapolitan novels, keeping readers engaged over four books and continuing to stoke “Ferrante fever” for long after the first installment was published in 2012. The girls’ connection is what made HBO’s My Brilliant Friend such a critical success, and it’s what will draw fans back when the show returns for its second season. Over decades of their life and amid the turmoil of their country, Lenù and Lila—much like Matteo and Nicola—are alternately family, friends, strangers, and enemies, each of their paths painfully incomplete without the other.

I was a 16-year-old student at the Bronx High School of Science, scribbling Concrete Blonde lyrics at my desk, when my English teacher abruptly called on me, without a heads-up or any preparation, to explain my thoughts on the word nigger in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Truth be told, I didn’t have an opinion, at least not a sophisticated, nuanced one, because I was a teenager reading Twain for the first time. I was there to learn like everyone else. But suddenly, as one of two black students in the class, I was expected to enhance the learning experiences of my mostly white counterparts. I’ll never forget the terrifying and confusing feeling of going from a part of the classroom to a classroom accessory.

Bronx Science is one of the three original specialized high schools run by the New York City Department of Education. These schools are required by state law to admit students based solely on the uniform Specialized High Schools Admissions Test. As I grew up and succeeded in this cut-throat, supposedly merit-based space, part of me feared any association with affirmative-action programs. I’d earned my way into Bronx Science, and I worried that anyone who didn’t understand how the system worked would assume I’d been given a leg up.

As an adult, I don’t oppose affirmative action—quite the contrary—but I support only certain justifications for it. Affirmative action should be implemented as part of a broader reparations program; the point should be justice, not “diversity.”

[Caitlin Flanagan: The dueling deities of Harvard]

I remember hearing a lot about the evils of affirmative action as a high-school student in the 1990s, and more than a few of my classmates figured I would all but automatically gain admission to every college I applied to. They were presumably reading stories about how the University of Michigan, in 1998, began using a 150-point scale to rank applicants, with 100 points needed to guarantee admission. The university gave underrepresented ethnic groups an automatic 20 points on this scale. Jennifer Gratz and Patrick Hamacher, both white residents of Michigan, claimed to have been harmed by this system in their applications to the university.

Their complaint eventually reached the Supreme Court in Gratz v. Bollinger in 2003. The majority opinion held that the University of Michigan’s use of racial preferences in undergraduate admissions violated both the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (President Lyndon Johnson’s legislation that originally advanced affirmative action). The Court did, however, rely on precedent to accept the argument that diversity can constitute a compelling state interest.

That precedent was the 1978 case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. Allan Bakke, a white male, had been rejected two years in a row by the University of California at Davis medical school, which had reserved 16 out of 100 places for qualified minorities.

Four justices defended the use of racial quotas to remedy the burdens placed on minorities by past racial injustice. As Justice Harry Blackmun wrote, “In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently.”

But in his majority opinion, Justice Lewis Powell ruled that while UC could use race as a factor in admissions, quotas were impermissible. He argued, moreover, that attaining a diverse student body was the only real interest asserted by the university that survived legal scrutiny. Powell, quoting an unrelated case, emphasized that the “‘nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure’ to the ideas and mores of students as diverse as this nation of many peoples.”

In its reasoning, the Court suggested that the point of affirmative action was to foster a more varied classroom environment for “leaders,” thus shifting the intended beneficiary of the program from the historically discriminated against to the nation that had discriminated against them. And who are these “leaders”? The future, Powell implied, perhaps without realizing it, depends on white students’ exposure to the supposedly unique ideas and mores that qualified minorities should offer.

While the push for diverse representation in society is important, it has no place in the legislation of affirmative action. Besides not addressing the actual issues—discrimination and inequality—this ideology creates “otherness.” It breeds the singling out of people who haven’t traditionally held positions of power, people who are often seen as either inferior or astonishingly exceptional, and therefore spectacle. This ideology demands wisdom from an ignorant 16-year-old that, rightly, the state should offer.

Affirmative action should be about reparations and leveling a playing field that was legally imbalanced for hundreds of years and not about the re-centering of whiteness while, yet again, demanding free (intellectual) labor from the historically disenfranchised.

[Read: The problem with how higher education treats diversity]

Affirmative action, whatever the rationale, has also never been the only, or even the most important, advantage in college admissions. Luke Harris, a Vassar professor, and Kimberlé Crenshaw, a professor at Columbia University and UCLA—both critical-race-theory pioneers—have noted that what got lost in the University of Michigan fight was that students were also awarded 10 points for attending elite high schools, eight points for taking a certain number of AP courses, and four points for being legacies. That’s 22 points that certain affluent and middle-class students had built in that poor, first-generation college students had little or no access to. This structure rewarded students who already benefited from living in upscale neighborhoods, who had successful parents or parents who, at the very least, knew how to succeed in “the system,” and who continued to benefit from the affirmative action of not descending from people who for generations were banned from reading, buying property, and living in safe neighborhoods with decent schools.

Somehow, advantages of this sort are often invisible to the general public. And if they’re made visible, the most coddled people in American society tend to get their feelings hurt—and insist on their self-worth. This dynamic explains the theater of defensiveness that played before the Senate Judiciary Committee in September 2018, as then–Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, who attended one of the most expensive prep schools in the nation and who is the son of a lobbyist and judge, sneered, “I got into Yale Law School. That’s the No. 1 law school in the country. I had no connections there. I got there by busting my tail in college.” Kavanaugh’s grandfather Everett Edward Kavanaugh went to Yale as an undergraduate. If Kavanaugh truly does believe that he is an island of his own merits, his lack of historical knowledge and his lack of awareness of his own privilege are terrifying for any judge, let alone a Supreme Court justice who could soon preside over affirmative-action cases.

[Read: The weakening definition of “diversity”]