Newt Gingrich turned partisan battles into a vicious blood sport, wrecked Congress, and paved the way for Donald Trump’s rise. As McKay Coppins reported in November, the former speaker of the House is now reveling in his achievements.

I couldn’t help noticing that the lessons Newt Gingrich takes from nature are only those that reinforce his particular worldview. Thus the usual nods are made to survival of the fittest, and women are expected to bow down before the obvious superior strength of dominant males, but no mention is made of the nurturing behaviors of countless animals or instinctual traits that help ensure the survival of groups. The ecology of our planet is so much more complicated than Gingrich’s filtered view, and while I don’t know whether we necessarily ought to be basing our political decisions on any examples from nature, what I see is just one more wealthy white man using any means to justify a position of power. What a pity that he was able to influence our country.

David Ohannesian

Seattle, Wash.

There’s no question that Newt Gingrich was an important figure, but he was an inevitable important figure. If Gingrich hadn’t ended Democratic dominance of the House, someone else would have. There were tensions in the Democratic coalition that could not be avoided. The Democratic hammerlock on the House was out of step with the composition of the American electorate. The tidal forces of cultural conflicts launched decades before were going to tear apart Congress in the same way they’d torn apart campuses and caused conflict at kitchen tables.

So, no, Gingrich didn’t break American politics. But he did help break a progressive monopoly on the House, which the GOP has controlled 20 of the 24 years since. And given the aggression and incivility they overlook on their own side, it’s clear that for many commentators on the left, ending Democratic dominance is Gingrich’s truly enduring sin.

David French

Excerpt from an article on nationalreview.com

People who think Newt Gingrich “turned politics into a vicious blood sport” clearly don’t know enough about Lyndon B. Johnson. He wantonly destroyed reputable people for the benefit of the oilmen who bankrolled him. Power-hungry politicians of both stripes have done plenty to destroy civility.

Paulette Arnold

Evanston, Ill.

What are we to make of the deathbed confession of the political operative Lee Atwater, newly revealed, that he staged the events that brought down the Democratic candidate in 1987? In November, James Fallows asked this question.

The saddest part of this story: Lee Atwater, confronted by his own looming death, realized that his brand of campaigning by lies, innuendo, and distraction was harmful to American democracy. But his repentance was too little, too late. In the years since, these techniques have become the stock-in-trade of political operatives.

The poisonous, dangerously fractured political landscape we now have to deal with has been manufactured by Atwater’s disciples.

Howard Schmitt

Green Tree, Pa.

It would also be interesting to ponder what would have happened without a Lee Atwater. Probably because of my age, I tend to think of Atwater as the original gremlin. I once naively thought that his deathbed show of conscience and regret would be impactful. But we’re now besieged with evil gremlins copying and amplifying his dirty deeds. One dies, and 10 more pop up.

Are we capable of hitting the reset button? Or are we stuck with this political savagery until the planet explodes?

Tanya Hilgendorf

Ann Arbor, Mich.

The Bible teacher Beth Moore gained her following by teaching scripture to women—and being deferential to men. Now her outspokenness on sexism could cost her everything, Emma Green wrote in October.

I heard Beth Moore speak in 2017 in Orlando, Florida. I was blown away by her sincerity and truthfulness. This article perfectly captures what I saw and heard that day, and much more.

I am one of those Christians who feels sort of stuck between the cracks of the current atmosphere—not at all in agreement with my fellow Christians who seem blind to the character flaws blatantly displayed in both the White House and the Church, but also understanding their cry for some feeling of control over the flow of secular liberalism, which now dominates American culture. I think their hope is sadly misplaced in the present administration.

This article has let me know that I am truly not alone in my feelings and thoughts. Sometimes a voice in the wilderness is all the Lord God needs to change the world. Go, Beth Moore, go!

Pastor Ron Barnes

Word Place of Northern California

Sacramento, Calif.

Until 2016, I considered my foundational belief system to be in line with the evangelical movement. I, too, voted for a third-party candidate and no longer identify with evangelicals because of the very same attitudes Beth Moore is describing. I now call myself a “Christ follower.” I am 58, a woman, working, white, with a master’s degree. I still have strong Christian core values but cannot tolerate the “good old boy” system apparently tolerated by evangelical Christians.

Terri Simpson

Little Rock, Ark.

This is a well-written identification of a significant shift that is largely going unnoticed. For so long, the conservative platform has taken its Christian voters for granted, much as the Church has often taken for granted the reticence of its women.

I’m so thankful for Beth Moore’s intelligent and humble fearlessness—a powerful voice for an often unheard and underled population.

Angela Hougas

Delavan, Wis.

Thank you for writing about Beth Moore. She spoke at my church’s women’s conference, and I had the pleasure of hosting her. You find out a lot about a person behind the scenes. She is the real deal: a kind, compassionate Jesus lover.

Emma Green writes, “Christians of color have expressed rage over what they see as abandonment by their brothers and sisters in the faith; many have even left their congregations.”

The problem is much larger than you state, and it’s not just people of color who are leaving the Church. People of all races who proudly call themselves “exvangelicals” have left the Church not only because of its tolerance for sexism but also because of its silence on matters related to racial discrimination.

As a person of color, I wouldn’t say the Church has newly abandoned me. Instead, I would say that the Church has persisted (since slavery) in its dismissal or denial of matters of importance to people of color. Throughout the years, people learned to grin and bear it and just “focus on Jesus,” which supports the concept of Christian business as usual. That is changing as we acknowledge that real unity and fellowship extend far beyond Bible study and into care for the lives of the people you say are your brothers and sisters in Christ.

Jocelyn Williams

Sacramento, Calif.

“Newt Gingrich Says You’re Welcome” (November) misstated Callista Gingrich’s age at the time she began her relationship with Newt Gingrich. She was not 23; she was 23 years younger than Newt.

To contribute to The Conversation, please email letters@theatlantic.com. Include your full name, city, and state.

Hanna Barczyk

Hanna BarczykThe Archer’s Paradox is a curiosity of physics according to which an arrow, if it flew straight, would miss its target. The path from bow to bull’s-eye twists and curves, imperceptibly but inevitably. Archery is the source of a great many metaphors in Hark, Sam Lipsyte’s new novel. (The word metaphor is the source of a self-conscious groaner of a pun—What’s a metaphor? It’s for cows to graze in—that is repeatedly invoked.) The title character, a self-help guru and putative messiah named Hark Morner, preaches a life-transforming practice called “mental archery,” whose vaguely described techniques, including thought exercises and physical poses, promise improved focus for distracted modern souls. “Focus on focus” is one of Hark’s mantras.

The Archer’s Paradox isn’t mentioned in the book, but a version of the rule surely applies. The novel’s tone and premise point toward satire, a mode that depends on accurate aim and swift, sharp impact. Lipsyte has a full quiver and a range of targets that include cosmopolitan culinary trends, urban-parenting dogmas, digital-workplace dynamics, and the arrogance of the technocratic ruling class. But satire is especially hard to pull off right now, its objects at once too obvious and too obtuse for effective puncturing. The dystopian imagination, looking for intimations of disaster that might be exaggerated for cautionary or corrective ends, finds itself beggared by reality on a daily basis.

Lipsyte, casting his eye toward a semi-plausible near future, has an astute ear for corporate and therapeutic idioms and how they echo each other. He knows the habits and attitudes of world-beaters and slackers alike. The universe of Hark looks pretty familiar, although politics, the bane and boon of most contemporary satirists, receives little more than a lazy, glancing shot:

He’s not an evil man, this president, nor a good one. He was elected to undo the catastrophic policies of his predecessor, who was herself elected to undo the apocalyptic agenda of the man before her, but it all seems too late for that these days, mostly because it’s always been too late, though now, pundits agree, this moment is steeped in a radical and irrevocable lateness, a tardy totality heretofore unseen.

An update flashes: president has not ruled out ground forces in bulgaria.

That’s enough of that, just so we’re clear on what and whom Hark is not about.

It’s only partly about Hark Morner himself. A guileless young man who survived an abusive childhood and dreamed of a career in stand-up comedy, he got his start in the business-seminar business as a ringer. “For a semi-ample fee,” the narrator explains, “Hark would attend a corporate gathering, a shareholders meeting or sales conference or tropical team retreat. The bosses would bill him as an expert in some esoteric practice—knife yoga, reverse hypnosis.” But in the midst of his presentation, “Hark would shepherd the sermon weirdward,” startling the captive audience. In would barge a top executive, staging an instant morale boost for the team. “You don’t need some loser to yammer on about stress and productivity,” the boss would declare as Hark was ushered off the premises with a discreetly proffered check. “You’re the most productive fucking stress cases in the country! You win!”

At a certain point, the impostor began to believe his own spiel. The grifter and the mark became one. “The joke drained away and Hark retired his jester’s bells, his craven prance, shed his fool’s skin, slithered out, translucent, sincere,” and became the evangelist of mental archery. After a while, other people started believing too, and it’s the inner circle of those believers—the apostles and disciples, the handlers and enablers—whose conflicts and ambitions supply the vectors of Lipsyte’s busy plot.

Principal among them is Fraz Penzig, Hark’s advance man, adviser, and occasional big-brother figure. Fraz is a familiar type of guy for anyone who has read Lipsyte’s three previous novels or lived in proximity to overeducated, underachieving North American heterosexual white men in the past 20 or 30 years. Lipsyte is a bard of male malaise, an anatomist (sometimes literally) of mostly non- or semi-toxic dudes who are disappointed in themselves and the cause of disappointment in others. His first novel, The Subject Steve (2001), was about a caption-writer in his 30s suffering from a mysterious, possibly metaphorical disease.

That book was followed by Home Land (2004), Lipsyte’s breakthrough, a scabrously funny indictment of both aspirational bourgeois mores and the resistance to them, composed in the form of updates to a high-school alumni bulletin from a loser named Lewis. Steve and Lewis were followed in the Lipsytean pantheon of almost-lovable nonwinners by Milo Burke in The Ask (2010), a Gen X man-child approaching middle age and struggling with monogamy, parenthood, and career discontent in the shadow of generational obsolescence.

As someone who has been there—who’s still there, thickening and graying as the Millennials and the Gen Z kids dethrone my idols and refuse to laugh at my jokes—I regard The Ask as one of the most unbearable and hilarious books I’ve ever read. Accordingly, I had great hopes for Hark, which might have been a mistake, given that the cumulative lesson of all of Lipsyte’s fiction (two books of stories, Venus Drive and The Fun Parts, in addition to the novels) is that low expectations are the only reasonable kind.

They can also lead to a dead end, to a state of auto-fatigue that Fraz acknowledges early and that he hopes might be cured by mental archery:

He’s lived too long in exile from himself, faking his freedom, refusing even to wear a tie, even to family funerals, even a clip-on, extolling the virtues of porn to his wife, hiding out in the gym, stuffing himself with fried pickles and an experimental mix of mint and mango ice cream. He’s weary of his contrarian pose, tired of his schemes, the funny T-shirts, the penny stocks, the fantasy bandy … But it’s different now. Fraz feels called. To mental archery, and what may lie beyond, and definitely to Hark, or the idea of Hark, or the radial heat of Hark.This can be read as the novel’s thesis statement, its artistic wager. Hark, while starting from the familiar place of self-numbing irony and self-pitying privilege, wants to strike out in a new direction and, like Hark himself, trade foolishness for sincerity, cynicism for authenticity, navel-gazing for heroic discipline.

Simon & Schuster

Simon & SchusterFor Fraz, at 47, the old habits are hard to break. And Lipsyte often seems trapped in a voice and sensibility that he no longer entirely believes in. Focus, the attribute Hark champions above all else, is what Hark lacks. Its attention splinters among half a dozen characters, none of whose dramas quite commands the reader’s full engagement. Fraz’s stalled marriage to Tovah (whose tech job supports the family) occupies a fair amount of space. The parents of precocious 8-year-old twins named David and Lisa, they have drifted into a state of low-level irritation, at least on Tovah’s part. Tougher and generally more competent than her husband, Tovah is a quintessential cool girl, outfitted with sufficient sass and brass to armor her creator against any implication of misogyny. But she’s hard to distinguish from the other women in the novel: Teal Baker-Cassini and Kate Rumpler, who work alongside Fraz in Hark’s world (though Teal dabbles in marriage counseling and Kate’s main thing is pro bono organ trafficking), and Meg Kenny, a late and decisive convert to the mental-archery cause.

The women aren’t the only characters who blur. Though Hark has a distinctive way of talking—in koans and riddles and great confessional gusts—everyone else sounds pretty much the same, including David and Lisa:

“Lisa, David, how’s school?”

“Daddy, I’m glad you asked,” Lisa says. “It’s a fucking shitshow.”

“Lisa, can you be more specific.”

“Okay, Daddy. School’s like a factory where they make these little cell phone accessories called people.”

“It’s more like a tool and die factory,” David says. “They turn us into tools and then we die.”

“I like that,” Tovah says. “You’re both very creative.”

That last maternal pat on the head is one of many instances of ventriloquized self-praise on Lipsyte’s part. Reading Hark can feel like being trapped in the writers’ room of a sitcom two seasons past its prime, except that the staff members desperately trying to top one another and laughing at their own jokes are all the same guy.

Lipsyte will often introduce a comic detail that registers just how zany his fictional world is—and also how knowing his inventions are—and then induce his characters to riff on it. For example, at one point Tovah and Fraz schedule a date at a restaurant described as “a new Thai-Irish fusion sensation,” the existence of which is not all that amusing to begin with. (What’s with all these crazy restaurants, amirite?) Lipsyte has fun with the dishes such a place might have, like Thai-basil corned beef and County Cork Curry Delight, before allowing the characters to deliver the punch line. “Maybe we should order some wine.” “Irish or Thai?” “See, you’re so witty. Total package.”

Once you notice this tic, it can drive you a little nuts, as can Lipsyte’s tendency to stack up verbs with commas (“Fraz orders a sexy new stout from Vermont, peers up at the TV. Ball game graphics zoom, burst.”) and his habit of treating a character’s consciousness as a basement comedy club:

Kate looks to the driver. He seems oblivious behind his bulletproof plastic. The hack license affixed to the separator says the driver’s name is Ali Islam. Is that like somebody named Marjorie Judaism or Larry Christianity? She wouldn’t know. She wouldn’t know how to know.But somebody might. Most of all, the gestures toward Major Novel status in Hark—Pynchony, Lethem-esque names like Hark Morner and Fraz Penzig, Dieter Delgado and Teal Baker-Cassini; Infinite Jesticles in the form of wacky brand names and inscrutable terrorist organizations; intimations of apocalypse that accelerate in the book’s final pages—have an air of desperation. The impulse to make big thematic statements is accompanied, and perhaps defeated, by a joke-making reflex, as if attempted seriousness has triggered a kind of autoimmune response:

To say it once more, history hides. It hides inside every new interpretation of an interpretation. It hides, in fact, like a gem stuck up the ass of the flabby young man called history at the outset of this tale. History is both the hidden gem and the man in whom the gem has been noiselessly, perhaps greasily, inserted. “Intelligence” may be defined as the ability to behold both of these word pictures at once, in the way you never could with a pair of nipples.In this and other ways, Lipsyte’s writing has a habit of disappearing up its own … never mind. And yet solipsism is the very tendency Hark tries hardest to fight. It’s also the hardest thing for contemporary novels, especially by men working in self-conscious relation to the traditions of postmodernism, to avoid. The imperial sweep of the old masters has become suspect, and the false modesty of auto-fiction (at least as practiced by some of Lipsyte’s peers) can be a drag. Surely some new route can be found, some stance that will allow the bowman to pierce the fog of the self and strike the hide of history.

Or maybe not. I have nothing but sympathy for the predicament out of which this book arises, and nothing but impatience with its way of addressing that predicament.

Capitalism isn’t going anywhere. Capitalism’s not natural, but at this point, neither is nature. You have to dance with the one you came with, Fraz has heard, even if it’s hard to picture escorting a global economic system to a line-dancing barn or a strobe-stabby club. Maybe it’s more like Fraz’s high school prom, where you pick up capitalism at its house, pin a corsage to its gown, and later have drunk sex in a Lysol-tangy motel room down the shore.

Or should Fraz, in fact, wear the corsage?

A metaphor may be a place for cows to graze, but this is bullshit.

This article appears in the January/February 2019 print edition with the headline “The Bard of Male Malaise.”

Earlier this month, Julianna Goldman described the many structural challenges facing mothers who work as TV-news correspondents. “Retaining moms in TV news matters not just for the moms, but for audiences, too,” she wrote. “The more women there are in TV news—from the top on down—the better and more diverse stories there are for the public to consume.”

While I’m certain Ms. Goldman’s story is accurate, the headline is not. It should be changed to “It’s Almost Impossible to Be a Mom in National Television News.” Without the enormous burden of world travel, many mothers have successful careers in local television news, which is still the No. 1 source for news in the United States, according to recent Knight Foundation research.

As a local-TV-news director for the past 30 years, my experience until I left the business this year was that the number of on-air women was growing, and in many newsrooms, they are the majority of anchors and reporters. Women were the majority of on-air journalists at my most recent station in Cleveland when I left, and on the assignment desk. The majority of these women were mothers. This is good for local TV news because mothers are a key part of the audience. They watch, in part, according to local-news research I’ve seen, to get information to keep themselves and their families safe.

The most recent Radio Television Digital News Association survey showed a new record high for women working in local TV newsrooms, 44.4 percent. This is still behind the national full-time U.S. workforce, of which women make up 47 percent. The survey also showed a new record for female news directors, the managers who do the hiring, at 34.3 percent. The highest percentage of these women were in the top-25 TV markets.

While all newsrooms—and workplaces—in our country still have a long way to go to support working mothers and fathers, local TV news certainly seems to be a better option right now than the national networks.

Fred D’Ambrosi

Cleveland Heights, Ohio

As a mom of three years and a local TV-news anchor and reporter of 15 years, I cannot express my gratitude to Julianna Goldman enough for shedding light on these truths so many TV moms have quietly experienced. For me, this article was an eloquent affirmation of all the ideas I’ve wanted to express in explaining my “choice” to stay home with my babies.

Name Withheld Upon Request

The article “It’s Almost Impossible to Be a Mom in Television News” resonated with me so much. Though I am not a mother, I quickly found the world of broadcast news to be particularly taxing for women. I started out as a reporter and evening anchor in northern Michigan, then landed a job as an evening reporter at a news station in South Bend, Indiana. One of the greatest challenges was balancing all of the responsibilities that came with reporting one-man-band style. It wasn’t enough to simply get the story. You had to manage the equipment, stay on track with your deadline, be actively posting to social media while reporting, and do all of this in flawless makeup, perfectly coiffed hair, a skintight dress, and heels. Even when I was promoted to morning anchor two months into my reporting role, there was still enormous pressure on my physical appearance, and the job consumed every aspect of my life.

By the time my contract was up, I was suffering from health issues related to sleep deprivation and had zero personal life. Although the career was exciting and I was proud of my work and my quick promotion, I knew it wasn’t sustainable, especially if I wanted to have a family in the future. I felt like I had to choose between having a seemingly glamorous but all-consuming career and having an ordinary career but fulfilling personal life. I decided the latter was for me.

Allison Preston

South Bend, Ind.

I could have written Ms. Goldman’s piece myself, as at the same 15-year mark I also hung up my microphone.

I’d worked in four TV markets as an anchor and as a news reporter, settling in Portland, Oregon. But everything changed when I had two daughters. Television news requires a nanny, family living nearby, or another parent at home. At any time, I would be called—“Can you get in here right away?”—and I’d scramble to go in. I’d give it my all, and would work until the wee hours of the night or until the crack of dawn when I had to. But of course, no matter what shift I worked, I still had two preschoolers who needed my full attention the next day. I dozed off more than once at the children’s museum.

I was very fortunate: I was allowed to work out a part-time schedule the last five years of my career. I figured I’d go back to work when the girls got to elementary school. As a result, I tried to go in whenever I was needed.

It didn’t matter in the end. When an anchor job came up that I really wanted, it was filled by a younger woman before I was given my token audition. My news director told me, “Stay here as long as you want, we love having you here ‘on the bench.’” I’d been mommy-tracked. I felt humiliated, and quit the next day.

I agree, having more women as news directors and station managers may be the answer for some women who can make it work. I’m not sure it will ever be a family-friendly career. Perhaps that is the better message. I’m glad to hear younger reporters have already planned their exit.

Teresa Luce Spangler

Lake Oswego, Ore.

Julianna Goldman’s story about her experience as a mother and television-news correspondent rang a familiar bell for me. My mother was the great journalist (and great mom) Marlene Sanders, who was a pioneering correspondent for ABC and CBS News starting in the 1960s. In one respect, she had it easier than her successors today because the technology did not allow for the current, incessant pressure for live shots. But in most respects, things were worse—because she was nearly alone as a working mother and correspondent in those days and because the world was an even more sexist place. (When Sam Donaldson, who was a colleague of my mother’s, and later mine, at ABC News, found out I was her son, the first thing he said to me was, “Boy, we really discriminated against women in those days!”) I don’t have a great answer for the dilemmas posed by Goldman’s piece; I’m “talent” in the industry, not management. I just wanted to offer a word of solidarity and support for Goldman and my colleagues who are struggling with the same issues.

Jeffrey Toobin

New York, N.Y.

At the outset, I want to thank everyone who responded to this piece by sharing stories of their own. I had my second child the day before the piece was published (talk about timing!) and I have been overwhelmed by the feedback from other industry moms. A number of you told me that you realized you were not alone and that you felt like your feelings were validated as I laid out the institutional and structural challenges of balancing motherhood and a career in TV news. I too felt validated hearing from all of you. I also really appreciated stories from moms who described how they’ve found ways to pursue their dream job in the industry and raise a family.

The feedback also highlighted challenges faced by others across the industry, including producers, fathers, same-sex couples, single parents, and mothers in local news. There are definitely follow-up pieces to be done! As Fred points out, my focus was based on my own experience working in national news, and I’m heartened to see that there is an upswing in female local-news directors, especially because, as he noted, local news is still the dominant source of news in the United States. At the same time, as Allison and Teresa point out, local news presents a unique set of challenges for working moms—unpredictability, odd hours, slim budgets, and reporting in one-man-band style.

I certainly never intended to say that being a mom in TV news is impossible. It certainly is not, and I am in awe of the mothers I know and heard from in the industry who are producing and reporting stories of critical importance. While I agree that TV news will always be uniquely challenging for moms, I also believe that management can do more to help make it easier. As Jeff shared, Sam Donaldson had the self-awareness to acknowledge the industry’s history of discrimination against women, and hopefully other powerful figures in TV news will continue working on making the environment better for women as well as mothers.

The average American farmer, according to the most recent United States Department of Agriculture data, is white, male, and 58 years old. Just 8 percent of America’s 2.1 million farmers identify as anything other than non-Hispanic white; only 14 percent are women. And as the average age of American farmers has risen over the past 30 years, the federal government has taken small steps to address a situation that if left unaddressed, would almost certainly prove to be a crisis for American agriculture and the American food supply.

The new farm bill, which passed through both houses of Congress last week and is waiting on Donald Trump’s signature, nearly triples funding for the only two programs specifically designed to support beginning and socially disadvantaged farmers; in other words, farmers outside the current dominant—and aging—demographic. The two grant programs—the Socially Disadvantaged Farmers and Ranchers Program, often known as the 2501 Program after its original section number, and the Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program—will exist within one new initiative, called the Farmer Opportunity Training and Outreach (FOTO) Program.

[Read: The art of the farm-bill deal]

While the two programs will remain distinct, putting them under the umbrella of the FOTO Program will allow them to better coordinate with each other. The programs have different target populations and slightly different goals. Both grants are designed for programs that help people who might feel isolated from the dominant American-farming demographic. They also endeavor to bring into farming people who might otherwise be left behind by the often complicated regulations and bureaucracy of the USDA. “Now more than ever we need to build the bench for the future of farming,” said Senator Debbie Stabenow, the ranking member on the Senate Agriculture Committee, who was one of the primary proponents of the FOTO Program.

The FOTO Program will receive $435 million in funding over the next 10 years, small peas relative to the total cost of the farm bill, which the Congressional Budget Office predicts will be $867 billion over the same period. But for organizations working with farmers of color, veteran farmers, and new farmers, it’s a big deal.

“You typically think of agriculture subsidies as price supports going to the large commodity producers,” said Nicole Milne, whose organization, the Kohala Center in Hawaii, receives funding from both the 2501 Program and the beginning-farmers program. The FOTO Program provides another form of subsidies: grants for programs offering outreach, training, and technical assistance that “are an important form of support that small-scale producers are able to access,” she said.

[Read: The farm bill’s threat to food security]

Both existing programs fund others within organizations such as nonprofits, universities, and community organizations that serve under-resourced farmers. Their grants help farmers in radically different climates and in areas with radically different histories, guiding them through the complex world of regulations, loans, training programs, and other assistance offered by the USDA.

“That was a huge lift, to get all of these programs permanent authority and permanent funding. That’s going to be a game changer for folks that are working with the next generation of farmers,” said Juli Obudzinski, the deputy policy director of the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. The bill gives permanent funding to the program, which means that going forward, both programs will be protected from a drastic loss of funding like that which the 2501 Program suffered in 2013, and they will be at least partially insulated from the whims of an ever polarized Congress. The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition expects that the beginning-farmers program will take a small cut in funding in the first few years of the FOTO Program in order to shore up 2501’s funding, which was slashed in half as part of the last farm bill, in 2014.

Though racial disparities in American farming have always existed, especially when it comes to who owns the biggest and most profitable farms, the gap wasn’t always this wide. In 1920, for example, there were 925,000 black farmers, about 14 percent of the nation’s total. Now that number is around 45,000, a little more than 2 percent of all American farmers.That’s not by chance: In a 1998 settlement, the USDA admitted to systemic discrimination against black farmers. In 2010, it acknowledged similar actions against Native Americans. In recent years, Hispanic farmers have also alleged discrimination by the federal agriculture agency.

[Read: A Republican plan could worsen rural America’s food crisis]

To help rebuild trust between the USDA and the farmers it’s supposed to serve, 2501 provides grants to community-based organizations, educational institutions, and nonprofits that do outreach and training for what the agency calls “socially disadvantaged” farmers and ranchers. That’s a group that has included black, indigenous, Latino, Asian, and Pacific Islander farmers since the program’s inception. In 2012, the grants were expanded to also target veteran farmers. Each demographic the grant program targets has a different history requiring a different solution—many black farmers in the South need assistance getting titles for their land so they can apply for USDA programs, for example, and Native American communities in Oklahoma typically benefit from guidance in navigating the complex legal landscape that comes with farming tribal land.

Henry English, who heads the Small Farm Program at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, an 1890s land-grant university in southern Arkansas, credits the 2501 grants with his program’s ability to connect the region’s black farmers to technical assistance for loan applications. “Before this grant, we wouldn’t say anything about the farm-loans program. We would only talk about production,” how farmers maximize their output, he told me. “With [2501], not only do we talk about the program, the money that’s available, we also help them put together the USDA loan applications.”

English and his staff help local black farmers get loans from the local USDA office, which they had viewed warily, given its history of discrimination in the region. English estimates that his staff works with about 200 farmers every grant cycle. “We have a long history of working with them, so they feel really comfortable coming” to the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, he said.

But the 2501 Program has struggled to maintain consistent levels of funding, and has been shifted around between a number of USDA offices. When Congress couldn’t agree on a farm bill the last time it expired, in 2012, 2501 lost funding for an entire year. When a new bill finally passed, in 2014, the program still lost half of its allocated funding, going from $20 million a year to $10 million a year. In the four years since, Obudzinski says, that’s had a major effect.

“Obviously, you expand the pool of applicants and the pool of communities that are trying to be served by a program, and you cut the funding in half—we’ve seen a number of impacts,” she told me this fall. “Some of them have had to cut their programming, some of them have had to lay off staff.” (Even with a set amount in “mandatory” annual funding, both the 2501 Program’s and the beginning-farmers program’s funding still fluctuates year to year, depending on what’s allocated in appropriations bills).

Many programs, such as the Kohala Center on the main island of Hawaii, receive funding from both 2501 and the beginning-farmers program. Milne, Kohala’s director of food and agriculture, told me that for nonprofits like Kohala, the funding allows their programs greater reach and more depth of service, especially given the relatively recent collapse of Hawaiis plantation-style agricultural economy.

“There is a lack of experienced agricultural producers and extremely limited access to capital necessary to reinvent those lands,” she said. By matching new farmers with retiring farmers, she told me, land can be kept in use and the financial burden on farmers just starting out can be greatly reduced. In addition to that, older farmers often serve as mentors for younger ones just starting out and can help close the knowledge gap between generations. Kohala has graduated nearly 200 people from its Beginning Farmer-Rancher Development Program, funded by a beginning-farmers grant, and 150 high-school students have completed its high-school AgriCULTURE program, which was funded in part by 2501.

The beginning-farmers grant program is a much more recent addition to the farm bill than 2501. It was created in 2008 and targets young farmers who are new to agriculture and need guidance in building and operating a successful farm or ranch. The program is a direct response to the upward-creeping age of America’s farmers, and works to train, educate, and mentor new farmers and connect them with other USDA programs that can help them get a farm operation off the ground.

Like 2501 grants, beginning-farmers grants are used for a variety of purposes: While one program in San Francisco trains young farmers in best practices for successful, profitable small farms in an urban market, another in northeast Georgia is focused on connecting current landowners with the resources they need to begin farming on their property. The flexibility of the grants allows for programs in different regions, with different needs, to run programs specific to their communities. And like 2501, most of the farmers served by beginning-farmers grants are small- and mid-size farmers—a rare benefit in a farm bill whose subsidies overwhelmingly go to massive producers.

But even with the farm bill’s permanent funding and a guarantee that the grants won’t be interrupted by congressional inability to pass a new bill, the FOTO program still isn’t perfect. The two grant programs will remain housed in separate branches of the USDA. In the past, that’s meant they’re administered differently, with varying levels of efficiency. A common complaint is 2501’s one-year grant cycle, set not by the farm bill but by an administrative rule-making process that happens after the legislation is passed. These short cycles can be prohibitively difficult for small nonprofits that don’t have the staffing capacity to apply for new grants every year.

“One year is very, very hard for a new program,” said English, of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Showing a measurable impact in the first year, especially if the grant cycle doesn’t align with the growing season, can be very hard for new, small organizations, he said. This is, in part, why universities make up a significant portion of the program’s grantees—many of them have dedicated grant-writing staff who can put together a polished application for 2501 or beginning-farmers funding from the USDA.

Still, despite the bureaucratic hiccups, the farmers who currently benefit from organizations funded by 2501 and the beginning-farmers program can now be sure that the training and technical assistance they rely on will continue, at least for the foreseeable future. And with mandatory funding for both programs expected to hit $25 million in the next few years, more organizations—serving more communities—will have a chance to build programs on the back of FOTO dollars.

A series of explosive Department of Justice filings—outside the special counsel’s probe—makes clear that Russia is a rogue state in cyberspace. Now the United States needs a credible system to take action, and to sanction Russia for its misdeeds.

Consider what we learned from last month’s criminal charges filed by the Department of Justice against the “chief accountant” for Russia’s so-called troll factory, the online-information influence operations conducted by the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg. The indictment showed how Russia, rather than being chastened by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s detailed February indictment laying out its criminal activities, continued to spread online propaganda about that very indictment, tweeting and posting about Mueller’s charges both positively and negatively—to spread and exacerbate America’s political discord. Defense Secretary James Mattis later told the Reagan National Defense Forum in Simi Valley, California, that Vladimir Putin “tried again to muck around in our elections this last month, and we are seeing a continued effort along those lines.”

In October, a 37-page criminal complaint filed against Elena Alekseevna Khusyaynova, who is alleged to have participated in “Project Lakhta,” a Russian-oligarch-funded effort to deploy online memes and postings to stoke political controversy, came along with a similar warning, from the director of national intelligence. Those charges came in the wake of coordinated charges filed this fall by U.K., Dutch, and U.S. officials against Russia and its intelligence officers for a criminal scheme to target anti-doping agencies, officials, and even clean athletes around the world in retaliation for Russia’s doping scandal and in an apparent effort to intimidate those charged with holding Russia to a level playing field. There’s also new evidence that Russia has been interfering in other foreign issues, such as a recent referendum in Macedonia aimed at easing that country’s acceptance into Europe.

[Read: How to run a Russian hacking ring]

At times, it’s seemed like every week this year has brought fresh news of Putin acting as the skunk at the global internet party. This fall also saw a new report from the security firm FireEye that concluded that the code used to attack a Saudi petrochemical plant came from a state-owned institute in Moscow.

Moreover, it’s also become more clear that the “global cybercrime problem” is actually primarily a “Russia problem,” as Putin’s corrupt government and intelligence services give cover and protection to the world’s largest transnational organized crimes, cybercriminals, schemes, and frauds that cost the West’s consumers millions of dollars. Earlier this year, the Justice Department broke up one cybercrime ring based in Russia whose literal motto was “In fraud we trust.” The Justice Department charged 36 individuals, many of whom live in Russia beyond the law’s reach, and outlined a scheme by which they stole more than a half-billion dollars. It’s hardly the only example from this year; last week, the FBI announced that it had dismantled two other cybercrime rings and charged eight people—seven of them Russian—with running a multimillion-dollar ad-fraud scheme. (Three of those charged were able to be caught overseas in friendly countries that respect the rule of law: Malaysia, Bulgaria, and Estonia.)

Ferreting out cybercriminal and intelligence operations and making them public are two prongs of a three-part strategy to change behavior. In recent years, we’ve gotten really good at the first two parts. In fact, while for years these cases were hidden away inside the government, we now release them routinely. This fall, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced that the Justice Department was changing its approach to election-meddling cases, with the default now to make such cases public as quickly as possible. The change coincided with the criminal complaint against Khusyaynova, detailing that the attacks on our elections are a problem of right now, not just a theoretical issue.

[Read: What Putin really wants]

As Rosenstein said earlier this year, “Exposing schemes to the public is an important way to neutralize them.” Making public such charges helps us be more resilient and more savvy consumers of online content—Russia’s attacks in 2016 succeeded in part because we weren’t expecting them and because people weren’t skeptical enough about consuming information online. Today, of course, we understand all too well that photos, images, and posts online could be the work of foreign trolls and bots.

While defaulting to public action is a good first step, it is not sufficient. The elusive third part of the strategy is what is most needed: making Russia pay a cost that deters the activity. The United States should move toward automatic retaliatory action, ensuring that in today’s fast-moving information environment a response doesn’t get bogged down in partisan politics or bureaucracy.

It was reported just before the November elections that U.S. Cyber Command was privately notifying Russian hackers that it’s on to them—warning them that the United States is watching and that if their actions continue, they’re likely to face personal retaliation, such as U.S. criminal charges or sanctions. While sanctions and criminal charges on operatives make it nearly impossible for targets to travel overseas and participate in global banking or commerce, and limit prospects, we can do more.

[Read: The coincidence at the heart of the Russian hacking scandal]

We should consider building more “dead man’s switches” into our counter-foreign-influence work—such as automatic triggers that, when foreign efforts are detected and charged, would put in place new sanctions authority and even boost our own government’s spending on democracy-building efforts that counter Russia’s influence campaigns. Russia might think twice about the value of investing the approximately $30 million allegedly spent on Project Lahkta if doing so would presumptively trigger tough new sanctions as well as a fivefold or tenfold American investment in democracy-building NGOs or institutions such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe that beam free and independent news in the Russian language.

Too often, the responses to these incidents get caught up in political debates and bureaucratic stalemates. The dead man’s switch would cut through the inertia by setting up our response in advance—putting Putin on notice that if our intelligence community concludes that a country has targeted our elections, either through online influence operations or direct attacks on the voting systems, that assessment would trigger automatic sanctions against the head of state personally as well as against senior government, intelligence, or foreign-business figures. One credible way to make Putin reassess the cost-benefit analysis of attacking our democracy would be to announce in advance that we’d target his personal wealth for sanctions or that his most powerful oligarch allies would have a harder time vacationing on their super-yachts in the Mediterranean.

After all, the greatest leverage we have is that as much as Putin seeks to undermine the West, his oligarchs, business associates, and even his country’s economy all rely on the West to live their life. If the world responds in concert, we can raise the costs and make it safer for everyone.

There are moments when it is wise to look back from whence we have come. Donald Trump’s recent tantrum in the Oval Office, his symphony of tweets, and his penchant for personal attacks and questionable alliances—all echoed in the media, on Capitol Hill, and across the nation—suggest that it is worth revisiting the first president’s “firm opinion” that those who follow him are bound by duty to behave at all times in a civilized and decent manner.

As a young man, George Washington copied down Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation, a list of 110 precepts compiled by Jesuits in the 16th century, for the training of young gentlemen. The intent of these rules was to shape the inner character of those who observed them by perfecting their outer behavior.

Washington was a slave owner, he sometimes broke his own rules, and much of what he prescribed and proscribed 275 years ago is as crucial to civilized behavior today as fish forks and butter knives. Nevertheless, some of the rules that Washington copied down as a youth seem more pertinent than ever:

1st: Every Action done in Company ought to be done with Some Sign of Respect, to those that are Present.

2nd: When in Company, put not your Hands to any part of the body, not usually Discovered.

6th: Sleep not when others Speak. Sit not when others stand. Speak not when you Should hold your Peace, walk not when others Stop.

22nd: Show not yourself glad at the Misfortune of another though he were your enemy.

35th: Let your Discourse with Men of Business be Short and Comprehensive.

40th: Strive not with your Superiors in argument, but always Submit your Judgment to others with Modesty.

41st: Undertake not to Teach your equal in the art himself Professes; it Savours of arrogance.

44th: When a man does all he can though it Succeeds not well, blame not him who did it.

50th: Be not hasty to believe flying Reports to the Disparagement of any.

56th: Associate yourself with Men of good Quality if you Esteem your own Reputation; for ‘is better to be alone than in bad Company.

58th: Let your Conversation be without Malice or Envy, for ‘is a sign of a Tractable and Commendable Nature; and that in all Causes of Passion admit Reason to Govern.

60th: Be not immodest in urging your Friends to Discover a Secret.

73rd: Think before you Speak pronounce not imperfectly nor bring out your Words too hastily but orderly and distinctly.

79th: Be not apt to relate News if you know not the truth thereof. In Discoursing of things you Have heard Name not your Author Always a Secret Discover not.

82nd: Undertake not what you cannot Perform but be Careful to keep your Promise.

89th: Speak not Evil of the absent for it is unjust.

110th: Labor to keep in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.

Brian Tyree Henry moves as if he’s been here before. His character on Atlanta, the Donald Glover–led FX dramedy, is a reservoir of slow-unfolding gestures, resigned shrugs, and hauntingly empty expressions. As Alfred, the despondent cousin of Earn, Glover’s ineffectual protagonist, Henry pays extraordinary attention to physicality. His maneuvers are deliberate: When Alfred finds a tenuous sort of fame as the rapper Paper Boi, you can see how celebrity wears him down. Henry’s investment in the character grants Alfred a gravity that serves as the show’s emotional core.

“I knew that Alfred was the Atlanta part. He is the one that’s born and raised there. Where people could come in and leave, he couldn’t,” Henry said when we spoke in New York City recently. “We all know this dude: We know what kinda Swisher he likes, we all know which grape drink he likes, we know which condiments he doesn’t like, we know what specials he likes, we know what fights he’s gonna watch, we know him. We think we know him, and it causes us to put a judgment on him.”

Henry’s Alfred—whom the 36-year-old actor never refers to as “Paper Boi”—straddles the conflicting worlds that many black men inhabit with fatigued equanimity. He balances career strife, familial expectations, systemic discrimination, and social ostracism. He does so knowing that neither the white music-industry gatekeepers he encounters—nor the majority of the black people around him—have much faith in his ability to succeed. Henry imbues Alfred with a kind of bone-deep weariness that belies the character’s years. The performance is at once unnerving and familiar.

Earlier this year, the actor’s work on the series earned him an Emmy nomination. It also caught the attention of Barry Jenkins, the director of the 2017 Best Picture winner, Moonlight. “It was clear that he was an actor who could basically traverse the entire spectrum of emotions—and that he could [do] it within scenes themselves, not necessarily over the course of a two-hour narrative,” Jenkins told me. “There was just something very deep and vulnerable about Brian’s performance.”

Jenkins’s latest film, an adaptation of James Baldwin’s 1974 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk, features Henry as the character Daniel Carty. As the formerly incarcerated friend of one of Beale Street’s protagonists, Henry is on-screen for less than 15 minutes, but his artful performance anchors the film. And if you pay attention, you’ll notice Henry nearly everywhere now: The Steve McQueen–directed heist film Widows sees him deploying an ominous determination in the role of Jamal Manning, a Chicagoan running for alderman against the legacy politician Jack Mulligan (Colin Farrell). Henry also voices the titular character’s detective father in Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse, lending a warmly authoritative figure to the animated superhero story. In these films, as in Atlanta, his performances tie scenes together: He can be agile and profound, menacing and open, composed and undone. Put more plainly, Brian Tyree Henry has the range.

Henry—and particularly his voice, a warm and solemn instrument—has bolstered several disparate choruses in recent years. He’s sung on Broadway as part of the original cast of The Book of Mormon and in the explosive new HBO series Room 104 (as Arnold, a character who wakes with no memory of the prior evening); invoked Southern colloquialisms on the animated Netflix series BoJack Horseman (he voices two characters in one of Season 5’s most poignant episodes); and debated difficult truths in his Tony-nominated performance as William, an embattled security guard in the Kenneth Lonergan play Lobby Hero.

It isn’t quite accurate to say that the actor is having a moment. No uncanny miracle is behind his rise, just slow, agonizing, all-consuming work. And so he is, in a word, tired—physically, yes, but emotionally as well. After all, his chosen roles don’t leave him when filming ends. Henry told me that he carries them everywhere. “I was just telling somebody, I need to let these characters go. I need to get a storage unit for these motherfuckers,” he said with a quiet laugh. “Because I take ’em home with me and I don’t know how to shake ’em … I don’t ever want them to be forgotten.”

As a young black boy in Fayetteville, North Carolina (and later in Washington, D.C.), Henry never envisioned that acting would be a viable career path. Early on, he noticed the entertainment industry’s lack of attention to the kinds of people whose interiority he knew best. “When I turned my television on, I didn’t see anybody like me. I definitely didn’t see anybody that was telling the stories that I was living in my own way,” he said of his childhood. “It didn’t make sense to me that [acting professionally] would be an option, but that didn’t mean that I couldn’t have fun.” And so he did.

The son of a veteran and an educator, Henry is the youngest of five children. By the time he was born, all his sisters were teenagers. Henry soon discovered his knack for capturing the contours of his family members’ personalities, and acting out stories became both a pastime and an escape. “I started imitating the people I saw around me, the environment I saw around me, because I didn’t know any better. It was a safety, it was fun to tell these stories and go out there and watch how it could change somebody’s day,” he said. “I remember being that kid—you know how at Thanksgiving it’s like, Go ’head, baby, tell that story the way you told it,” he added with a laugh, genially mimicking the tone many a black auntie has taken with her family’s most performance-inclined child.

Being the baby of the family also meant that Henry was often too young to consume the same cultural touchstones that the rest of his household did. The moments when he could catch up to the adults’ knowledge became some of his most formative experiences. “I remember seeing The Color Purple for the first time. I was born in ’82, so it had already been out, people had already received it, drank it, all that. I was just crying the entire time, and I couldn’t understand why it was hitting me that way,” he said.

The Color Purple, with Alice Walker’s intense emotional pulls and Oprah Winfrey’s iconic performance, left Henry feeling both devastated and newly aware of just how much he’d been missing. He recalled questioning his older family members incredulously about the film and realizing that everyone else already knew of its monumental power: “I was like, Oh, y’all already saw Color Purple? You knew that Celie and her gon’ do this, had this patty cakin’, and Mister was gonna do that?!” The effect that the film had—on him, but also on the people around him—resonated with Henry long after that initial viewing.

The actor counts that revelation among his Where were you when … ? moments, those inspirations that crackle in his brain long after the screen has faded to black. “I think that’s part of why I do what I do, because I like being at the front line of watching something unfold that could completely shift the way that people see things in the world,” he said. “And that’s kinda how I feel about Atlanta, that’s how I feel about me being a part of Book of Mormon, that’s how I feel about me working with Steve McQueen. I’ve been able to have that feeling of, I was there when this came together.”

As a student at Morehouse College and then the Yale School of Drama, Henry witnessed—and catalyzed—a number of auspicious pairings that brought black stories to life. During his undergraduate years, he played the lead role in a production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, the celebrated playwright August Wilson’s story about the lives of newly freed enslaved people. At Yale, Henry met the playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney, who would go on to write In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, the play on which Moonlight was based. “It was kinda just understood that he was the best person at the drama school at that time. Black or anything. Like, the best,” the Yale alumna and performer Melay Araya, a friend of mine, said of Henry recently. “But it was him and Tarell who were the standouts, one with acting and one with playwriting.”

More than a decade later, Henry’s work is once again concerned with both the threats that haunt black people and the bonds that hold them together. If Beale Street Could Talk, the Jenkins adaptation of Baldwin’s novel, is grounded in the story of Tish and Fonny’s love, and it traces the anguish the couple endures after Fonny is falsely accused of rape and imprisoned. As Daniel Carty, an old friend of Fonny’s, Henry appears only twice in the film. Still, Carty haunts the tale. “His story could easily be my story someday,” Henry said of his character, who warns Fonny about the horrors of the criminal-justice system after the two run into each other on the street. “Daniels are made every minute.”

In the film, Carty is at once joyful and anguished: He laughs with his whole body, he eats unreservedly, and he projects a vulnerability that impresses upon Fonny the burden of the injustice both men face. In the gutting final moments of the scene the two share, Henry’s performance pulses with the kind of rawness Baldwin’s work held so tenderly. “It takes a special kind of actor to have the impact that Brian had in this film,” Stephan James, who plays Fonny, said in an email. “He captured the feeling of an experience all too familiar for so many young black men in America.”

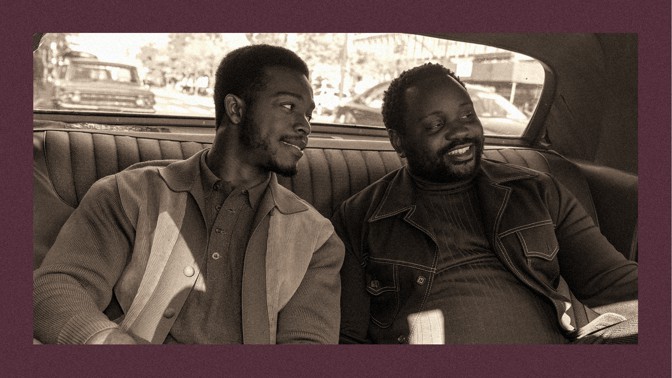

Stephan James, left, and Brian Tyree Henry, right, in If Beale Street Could Talk. (Annapurna Pictures / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)

Stephan James, left, and Brian Tyree Henry, right, in If Beale Street Could Talk. (Annapurna Pictures / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)It is a peculiar weight, the phantom menace of racism. It robs people of their rights while simultaneously insisting that their concerns are unfounded. “This shit is hard,” Henry said when we spoke, clapping on the table to punctuate. “Waking up every day as a black person in this country is hard. It is really hard to do. And sometimes you want to vent. And sometimes you need to know that someone is going to listen.”

Henry, who keeps a copy of Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time in his backpack, spoke with a pained appreciation about discovering the clarity and comfort in Baldwin’s work earlier in life. “I was so grateful,” he said, “but at the same time really saddened by the fact that here we are—I’m an ’80s baby, ’90s kid—and these same trials and tribulations that he was talking about then are still making me angry now. What’s his famous quote? ‘To be black and conscious in this country is to be angry all the time.’”

Daniel Carty is indeed angry, but beneath his righteous indignation lies fear and tremendous pain. For Jenkins, having an actor with Henry’s emotional range play the pivotal character was key to the film’s narrative success. “The scene with Daniel, with Brian Tyree Henry, falls almost exactly at the midpoint of the film,” the Beale Street director told me. “It’s one thing to intellectually describe what might be awaiting Fonny if his fate goes a certain way, but it’s another to have a character just completely embody what that fate could look like.”

Still, the scene Henry shares with James is remarkably warm. Even as the threat of incarceration hovers above them both, the men embrace each other—and Tish. It’s a gorgeous tableau, all the more wrenching for its vacillation between the friends’ affection for one another and a mutual, slow-building terror. “There’s a dichotomy, a duality that we all, especially people of color, have to walk within this world,” Henry said of what he’s learned from his Beale Street character. “And sometimes when you let your guard down for just that minute, it can be to your detriment, but at the same time we should all know what it’s like to let our guard down at least once.”

If Beale Street’s Daniel Carty and Atlanta’s Alfred Miles respond to the onslaught of white supremacy with tormented resignation, then Jamal Manning of Widows is intent on striking back. In the film, Henry channels the political hopeful’s existential fear about the conditions of his life and his community—what Henry sums up as a mentality of, How are we gonna get out of this alive?—with terrifying panache. The role is a rare one for the actor, whose prior characters often sublimated anger, collective or otherwise, into agitated silence.

In one of the film’s most electric scenes, the would-be alderman pays a visit to Veronica Rawlings (Viola Davis), the widow of a con man who disappeared with $2 million of Manning’s campaign money. The starkly lit moment, in which Manning threatens her while gripping her fluffy white dog, is deliciously evil. In his escalating intimidation, Henry matches Davis’s intensity without veering into cartoonish villainy. “It’s all or nothing with Brian,” the film’s director, Steve McQueen, told me. “When you’re up against Viola Davis, you gotta bring your A game, and it was beautiful to look at how these two artists made that scene.”

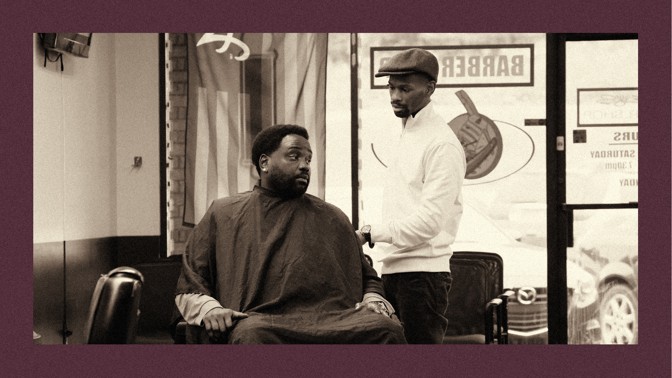

Daniel Kaluuya, left, and Brian Tyree Henry, right, in Widows. (Twentieth Century Fox / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)

Daniel Kaluuya, left, and Brian Tyree Henry, right, in Widows. (Twentieth Century Fox / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)Henry’s level of dedicated camaraderie on the set of Widows buoyed his fellow actors’ performances. His commitment to his collaborators is indicative of what could be described as Henry’s broader project: contributing to a landscape in which all actors have the freedom—and encouragement—to inhabit their characters as deeply as he does. “He was so prepared, I was as prepared as I could be, and I really felt like the two of us were just dancing,” Colin Farrell, who plays Manning’s political foe, Jack Mulligan, told me. “I don’t think Brian was just concerned with his own idea of how the scene should be.”

“I didn’t get one sniff of actorly self-interest off him,” he added. “For me, the most beautiful experiences to have are experiences where, yes, each actor is serving their character, but they’re serving their character as [part of] a greater whole. And I got that sense from Brian Tyree.”

This sentiment is shared by members of the Atlanta cast. The comedian Robert S. Powell III, who plays the hilariously erratic barber Bibby in the second season’s fifth episode, spoke of Henry’s patient partner work with near-reverence. “That was my first and only time ever acting!” Powell told me. “When I researched and found out that everybody on the set was classically trained and here I am, brand new, I didn’t know what to do. But [Henry] made me feel very comfortable.”

Brian Tyree Henry and Robert S. Powell III in an episode of Atlanta. (Guy D’Alema / FX / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)

Brian Tyree Henry and Robert S. Powell III in an episode of Atlanta. (Guy D’Alema / FX / Katie Martin / The Atlantic)“He knew every comma, every word. He was very, very on it … I didn’t know that the entire episode was going to be about me,” the comedian continued. “And then when I found out it was, I was kinda crammin’. So a lot of the ad libs that I did I had to do ’cause I had no idea what I was supposed to be saying at that time. My unpreparedness forced him to have to ad lib.”

For the actress Zazie Beetz, who plays Van, Earn’s sometime girlfriend and the mother of his child, Henry has been like a big brother throughout the show’s run. “He chooses to be on your team and on your side, sort of like a ride or die,” Beetz told me, recounting a time when the actor let her crash at his place for weeks after her Airbnb booking went horribly awry. “He was just like, We’re together in this.”

Henry’s capacity for empathy was evident during the shooting of the show’s second season, which follows Alfred as he grapples with numerous losses, including the death of his mother. Henry had recently lost his mother as well; while filming, he found himself wondering how to care not just for the people around him, but also for the character and for himself. “Alfred doesn’t have anybody to protect him. Everybody sees that he’s a bigger guy, that yeah, he’s got guns, yeah, he sells weed, so he must be inviting that stuff, right?” he said. “But there’s nobody there to really protect Alfred because everybody thinks he’s okay.”

“I really wanted this season [to] show my confrontation with my mental health and his confrontation [with his], which were one and the same. Because, life happens, right?” he continued. “For Alfred … I wanted him to know that somebody cared.”

The actor is still learning how to show himself that same compassion. It’s been a dizzying year of filming, publicity, and travel. There have been awards shows, premieres, and Broadway runs. The past several months have seen Henry filming five movies: Superintelligence, an action-comedy film with Melissa McCarthy; The Woman in the Window, a thriller also starring Amy Adams and Gary Oldman; The Outside Story, an indie feature about a workaholic editor; Godzilla vs. Kong, a monster film at the nexus of two massive franchises; and a reboot of the 1988 thriller Child’s Play alongside Aubrey Plaza. (Of his chaotic work life, he observed: “We like to torture ourselves as human beings, don’t we?”)

The punishing schedule has helped bring about the notable boost in his profile, but it’s also worn him down. “I haven’t had a chance to sit down and actually give myself praise for what I’ve accomplished and what I’ve done. I always feel like, Well, I still gotta do this, and I still have to get over here, and I still have to do that, which is something that we do all the time, especially people of color,” he noted. “Because you spend a lot of time being told what you can’t do, what you can’t have, how you should present yourself, and then when those moments of actual success come along, you’re already tryna figure out how to top that.”

For now, though, Henry is content to make himself at home in the work, to let the characters he inhabits burrow into him and offer guidance. “It’s given me a place to lay my heart out,” he said of the year’s challenging repertoire. “And not just to lay it out, but to receive things into it as well.”

“If I learned anything about doing If Beale Street Could Talk, it’s like—dammit, joy. Like, show the joy of us. Show the love of us. Show that it is obtainable. Show that we can thrive, show that we can feel something, dammit. Feel something.”

Desespero. Essa é a principal sensação de quem bate à porta de Débora Anhaia de Campos. Médica de família, ela ficou conhecida por ajudar mulheres que desejam interromper a gravidez. Primeiro, as pacientes querem tirar dúvidas básicas: “Estou mesmo grávida? De quanto tempo?”. Depois, muitas fazem logo a pergunta que as levou ao consultório: “Como posso abortar?”. Outras, com medo de uma denúncia, guardam o questionamento para si. Foi pensando nelas que Campos decidiu criar um vídeo-manual de redução de danos de abortos.

A médica ainda estava na faculdade quando sua irmã interrompeu uma gravidez e foi deixada sangrando por profissionais de saúde. A experiência em casa e a falta de informações sobre o assunto no curso de medicina, onde, diz ela, o aborto ainda é tabu, a levaram a mergulhar no tema. Quanto mais vulnerável a mulher, diz Campos, maior a chance de recorrer a “métodos inseguros”. Cabides, arames, agulhas de crochê e até soluções de água com soda cáustica ou sabão são usados por mulheres em tentativas de aborto, enumera. Em maio deste ano, Ingriane Barbosa tentou interromper uma gravidez colocando um talo de mamona no útero – a mamona é uma planta com propriedades tóxicas, comumente encontrada em jardins. A mulher de 30 anos morreu e deixou órfãos seus três filhos, ainda crianças.

São esses riscos desnecessários à saúde de quem já está decidida a interromper a gravidez que Campos quer ajudar a evitar. Seja num posto de saúde de Londrina, Paraná, ou em seu canal de YouTube, ela faz questão de deixar claro: aborto ainda é crime. Mas, ciente de que isso não impede que meio milhão de brasileiras recorram à prática, a médica fala abertamente sobre o assunto – que, feita de forma insegura pelas mais pobres, negras, adolescentes e periféricas, pode levar à morte.

Na Argentina, as leis restritivas sobre aborto são semelhantes às nossas, mas prestar informações sobre o tema é permitido. Lá, existe até uma rede de voluntárias que ajuda as mulheres a completar um aborto com segurança. Já a legislação brasileira não é clara quanto à divulgação dessas informações – o que levou Campos a sofrer perseguição. Em 2017, Filipe Barros, vereador de Londrina do PRB, denunciou a médica ao Ministério Público do Paraná, ao Ministério Público Federal, ao Conselho Regional de Medicina e à corregedoria do município de Londrina por “apologia ao crime de aborto”. O MPPR, o CRM e a corregedoria arquivaram os processos, mas o do MPF continua em andamento. Ela também sofre ataques pelas redes sociais e conta ser menosprezada por colegas de profissão pelo jeito como atua.

Em uma conversa por telefone, Campos falou sobre o manual, o tratamento que as mulheres que abortam recebem nos serviços de saúde e o que cada mulher pode fazer para evitar complicações.

Vale lembrar: Uma ação que pretende descriminalizar o aborto no Brasil até a 12ª semana de gestação está sendo discutida no Supremo Tribunal Federal. Mas, atualmente, só é permitido por lei o aborto em caso de estupro, risco de vida da mulher ou anencefalia do feto. Ou seja, no Brasil, interromper uma gravidez ainda é crime – que pode ser punido com prisão de um a três anos. Quem facilita um aborto também pode ser condenado à mesma pena.

Você é médica de família há mais de três anos. Já viu casos de mulheres que tiveram problemas de saúde ou morreram por abortos inseguros?

A minha irmã passou por uma situação assim e foi muito maltratada no hospital em que procurou atendimento. Foi feita uma curetagem e não deram a ela medicação para dor. Deixaram ela sangrando e depois mandaram para casa sem encaminhamento para exames, sem pedido de retorno. Eu já estava na graduação nessa época, no sexto ano. Ainda não tinha pensado em fazer Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, que agora quero fazer. Isso mexeu muito comigo. Aí passei a estudar isso. Vi muitas mulheres ao meu redor abortando. Só de você ser médica e feminista, as meninas já vêm pedir ajuda. Eu vi o quanto elas estavam abandonadas à própria sorte. Eu fui estudando e decidi fazer o manual porque já há manuais para sexo seguro e uso de substâncias, porque são assuntos que atingem homens. Na época em que minha irmã passou por isso, não havia acesso a nenhuma informação real e que fosse segura, mesmo buscando muito na internet. O que havia deixava ela ainda mais desorientada. Não havia acesso a documentos do Ministério da Saúde, por exemplo. Na época, minha irmã estava com cerca de 22 anos. Ela ficou bem, mas demorou bastante tempo. Logo depois da curetagem, ela teve hemorragia por 15 dias e não procurou um serviço de saúde por medo de ser maltratada de novo. Psicologicamente ela ficou muito abalada, não tanto pelo aborto, mas mais pela tortura que ela sofreu. Ela fazia psicologia e largou a faculdade. A vida dela acabou. Quando ela foi no serviço de saúde pela primeira vez ela falou que tinha usado remédio para abortar. Depois ela começou a ser xingada, maltratada, falaram que “se sua irmã soubesse ela não deixaria você fazer”. Nem chamaram o médico que estava de plantão. Não pediram exames de sangue, ultrassom. Você tem que encaminhar pelo menos para o posto de saúde para fazer acompanhamento, passar um método contraceptivo. Ela usava método contraceptivo e falhou. Ela engravidou, terminou o relacionamento, o cara comprou o remédio e deixou ela sozinha. Até hoje nunca falei com ela sobre isso. A gente nunca sentou para falar sobre isso. Ela foi muito humilhada.

Você percebe um recorte social dos casos que acompanhou?

As mulheres mais pobres não vão usar o misoprostol [medicação que induz o aborto, recomendada pela Organização Mundial de Saúde], que é o único método seguro. Então, é grande a chance que ocorram complicações, até morte. Nesses casos, são sempre mulheres pobres, negras, adolescentes, periféricas. Quanto mais vulnerável a mulher, maior a chance de usar um método inseguro, como introdução de objetos, substâncias tóxicas.

Você já viu profissionais tratando mal mulheres que chegam ao serviço de saúde com complicações de aborto? Como os profissionais deveriam agir diante desses casos?

Felizmente nunca vi na minha frente. Não conheço nenhuma que tenha procurado atendimento espontaneamente depois de abortar. Elas têm medo de serem presas. Isso só acontece quando o quadro fica muito grave, e aí outra pessoa leva. Os dois casos mais graves que já vi foram assim. Eram negras, pobres, muito jovens. Uma já tinha outro filho, não tinha parceiro, tinha sido abandonada. Fizeram aborto em gestação avançada, de quatro, cinco meses. Uma delas chegou com uma hemorragia muito grave, entrou em choque e quase morreu. A outra foi de Samu [ambulância da prefeitura] pro hospital e não sei o que aconteceu. Nesses casos, eu suspeitei que tinha sido aborto provocado por causa da gravidade do quadro delas. Mas não perguntei, porque pra gente [profissionais de saúde] não importa. Tem que ver o estado da paciente: se ela está com hemorragia, já é muito grave. Caso ela tenha introduzido um objeto ou substância tóxica, pode ter lesionado outros órgãos. Por isso é tão grave. O único jeito de abortar sem provocar infecção interna é com o misoprostol. Nos outros casos, o aborto sempre é causado por causa de uma infecção. Então, é uma roleta russa.

Há algum tipo de treinamento dos profissionais de saúde para lidarem com essas questões?

Não. Durante toda a graduação eu não tive nenhum treinamento sobre como atender mulheres em situação de aborto inseguro. Nos cursos de urgência e emergência nunca vi ninguém abordar essa questão. É um tabu tão grande que ninguém fala sobre isso. Quando acontece, as pessoas simplesmente não sabem o que fazer. Por isso tem gente que chama a polícia. No caso de uma tentativa de suicídio, ninguém pensa em chamar a polícia. Mas numa tentativa de aborto, sim.

No posto de saúde, as mulheres te perguntam sobre formas de abortar ou há medo? Como é essa aproximação?

Muitas perguntam. Já atendi mulheres que estavam com gestação indesejada, manifestando sofrimento. Uma delas disse que não ia prosseguir com a gestação, então tive uma conversa com ela explicando que era crime, mas que, caso realmente decidisse fazer, o único método seguro é o misoprostol. Indico o vídeo que fiz com o manual de redução de danos, digo: “pense bem, não coloque a sua vida em risco”. Tento saber se alguém está pressionando ela a abortar. De qualquer jeito, elas têm muito medo, muitas não perguntam. A maternidade não é incrível para todas as mulheres.

Você disse em entrevista à revista AzMina que, desde que se formou, tem procura diária de mulheres querendo saber sobre aborto. Algum caso te marcou mais?

São tantos casos. Todos me marcaram de alguma forma. Algumas desistiram do aborto. Outras disseram que só queriam falar com alguém sobre isso porque estavam com muito medo. Teve uma menina que o pai a obrigou a abortar. Eu evito ter informações sobre elas, apenas oriento para que elas não coloquem a vida em risco. Como médica, é o que posso fazer.

Conhece outras médicas que atuam assim?

Sim, muitas ativistas, feministas. Principalmente que fazem acompanhamento. Desde só ouvir a mulher que pensa em abortar até acompanhar o processo para ela não ficar sozinha, não correr o risco de passar mal. É um momento muito solitário, e, se a mulher passa mal, ela não consegue pedir ajuda.

Desde a publicação do vídeo, a procura aumentou? Quais as dúvidas mais comuns?

O principal ponto é o desespero. Elas chegam sem saber nada sobre [como abortar]. Digo para assistirem ao manual e respondo se a pessoa ainda tiver alguma dúvida. São dúvidas básicas, como a idade gestacional, se de fato está grávida ou não, ou, se ela já tem o remédio, qual a dose, como usar… Essas coisas. No manual, respondo tudo, não são informações proibidas. O protocolo do misoprostol, do Ministério da Saúde, é público.

Muitas mulheres têm medo de falar sobre o aborto com um profissional de saúde e serem denunciadas. Como é a questão do sigilo médico?

Nós, como médicos, só temos que ouvir e orientar para que não haja um novo abortamento. Para mulheres que já abortaram, há um grande risco de haver outro por falha de método contraceptivo, por exemplo. Mas, sim, tem profissionais que denunciam. Muitos acham que podem ser considerados omissos ou coniventes se não denunciarem, mas não é assim. A gente tem que respeitar a autonomia da mulher sobre o corpo.

Se o profissional denunciar a mulher que abortou, ela ainda tem alguma garantia legal com relação a quebra do sigilo médico?

Ela vai ter que denunciar o profissional no conselho da categoria e entrar com processo contra ele. Mas nunca vi isso acontecer.

Como é a ação do misoprostol no organismo?