The federal government on Friday evening stood on the verge of its second partial shutdown of the year, as congressional leaders and the White House scrambled to reopen negotiations hours before a midnight deadline. The talks represent the final act of unified Republican control in Washington—and a bookend to showdowns of years past over federal spending and immigration.

With President Donald Trump dug in on funding for a southern border wall, a shutdown of the nine federal departments Congress hasn’t already funded for 2019 appeared inevitable for most of the day. The Senate sat paralyzed for nearly five hours at one point, as Republicans were unable to muster the votes even to consider—let alone pass—a House spending package that included $5.7 billion in funding for the wall.

“We’re totally prepared for a very long shutdown,” Trump told reporters at the White House before the Senate had even finished voting. A prolonged lapse in funding could shutter national parks and museums over the holiday travel period and furlough hundreds of thousands of federal employees, forcing them to skip at least one paycheck over Christmas. (They will likely be paid retroactively whenever the government reopens.)

Read: [The Trump presidency’s lowest point yet]

By 6 p.m. eastern time, the best the Senate could do was to agree merely on the scope of 11th-hour negotiations, which would include leaders of both parties and the White House. The goal was a broad agreement that would fund most government agencies for all of 2019 while settling the dispute over border security that has driven the two parties apart.

“There is no path forward for the House bill,” Senator Jeff Flake of Arizona, the retiring Republican and Trump critic, declared on the Senate floor. “The only path forward is to a bill that has an agreement between the president and both houses of Congress. And the next time we vote will be on the agreement, not another test vote.”

Flake and another retiring Republican, Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee, had withheld their support from beginning debate on the bill the House passed, in a bid to jostle the leadership back to the bargaining table. The gambit worked—to a point.

It seemed clear by Friday evening that Congress would miss the midnight deadline, ensuring at least a brief lapse in federal funding. But with talks reopened, it was possible that any shutdown would be short and have a limited impact. The House planned to reconvene on Saturday, in a sign that a shutdown was likely.

If the negotiations break down again, however, it’s entirely possible that much of the government will remain closed for the rest of the year, until the new Congress convenes in January, with Democrats controlling the House majority.

This would be the second government shutdown of the year, after funding lapsed for four days in January as the two parties fought over immigration. But while Democratic demands for a deal that protected Dreamers precipitated that shutdown, the blame for this one will fall squarely on Trump and his demand for a taxpayer-funded border wall.

Earlier in the week, the Senate unanimously approved a measure to keep the government running through February 8; Republicans supported the bill in part because they’d been told Trump was likely to sign it. But the president reversed course, instead heeding calls from hard-liners in the House Freedom Caucus and conservative media to dig in on the wall.

After Trump informed Speaker Paul Ryan in a White House meeting that he would not sign the Senate-passed bill, the retiring GOP leader, in one of his final acts as a member of Congress, bowed to the president’s wishes and added $5.7 billion in wall funding, along with $7.8 billion in disaster relief. The bill passed Thursday evening largely along party lines, as Republicans defied a prediction by House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi that there were not enough votes for the wall in the House.

It was a pyrrhic victory for Republicans, however. The bill was doomed in the Senate from the moment it passed the House, as Democrats were united in providing enough votes to sustain a filibuster. On Friday, Trump made another futile bid to pressure Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Republicans to deploy the so-called nuclear option and eliminate the legislative filibuster. But McConnell, as he has repeatedly before, reiterated that he didn’t have enough votes to change the rules.

Read: [A shutdown would be a fitting end to the GOP majority]

When the measure came up in the Senate early Friday afternoon, not only did it not come close to the 60 votes it needed to advance, but it struggled to win the simple majority necessary to even begin debate. In a sign of how abruptly Trump changed course, McConnell had to hold the vote open for hours while he waited for senators to return to Washington; many had already gone home for the holidays on the belief that they had averted a shutdown.

By Friday night, both the House and Senate had returned, but lawmakers could only wait—and hope—for an agreement to vote on.

Programming note: The Daily will take a break on December 24 and December 25, and return each day with selections of the best Atlantic stories from this past year for the remainder of 2018. It’ll be back in full swing on January 2, 2019.

What We’re FollowingShutdown: Is it the most deadlocked time of the year? The U.S. government has been teetering on the edge of another shutdown, this time of the nine federal departments Congress hasn’t funded for 2019. The sticking point continues to be funding to build up the Southern border wall.

In 1995, then–Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich set the government on the path to a shutdown by sending President Bill Clinton a bill he knew Clinton wouldn’t sign. But the move had consequences for American politics that few could’ve foreseen; the same will be true of President Donald Trump’s standoff with Senate Democrats, however it resolves, writes Todd Purdum.

Any Given Friday: The White House foreign-policy team is in a bit of disarray—with Defense Secretary James Mattis’s resignation capping off the week—while the president pushes plans to withdraw several thousand troops from Syria and Afghanistan. (Though whether unending deployment should be framed as the only alternative to withdrawal is worthy of reconsideration, argues Conor Friedersdorf.) Stock markets are sinking in the U.S. and overseas. Are there staffers to replace the so-called adults in the room?

Cashless: As more and more stores go cashless and even cashier-less for the sake of efficient checkout experiences for customers, a clear group will be left out: the poor, and, in particular, unbanked people who may have low credit or work jobs that only pay in cash. Their options in the growing new digital economy are shrinking.

RBG: Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg underwent successful surgery Friday morning to remove two nodules found in her lungs during a CT scan last month. Though no other nodules remain, writes James Hamblin, that the two removed came in a pair could, alongside other factors, merit closer monitoring for metastatic disease in the future. For further reading, mull over Dahlia Lithwick’s piece on the irony of the modern feminist fandom around the justice.

—Haley Weiss and Shan Wang

Snapshot Since Tinder launched for all smartphones in 2013, dating apps have changed everything about how young people look for partners, introducing new problems and fixing some old ones. Ashley Fetters charts the complex evolution of today’s dating world. (Photo: Joe Readle / Getty)Evening Read

Since Tinder launched for all smartphones in 2013, dating apps have changed everything about how young people look for partners, introducing new problems and fixing some old ones. Ashley Fetters charts the complex evolution of today’s dating world. (Photo: Joe Readle / Getty)Evening ReadDNA tests have begun to reveal the genetic legacy of Jews who converted to Catholicism during the Spanish Inquisition. A recent study reveals the unexpectedly large extent of Sephardic Jewish ancestry that can be traced to Latin Americans today, writes Sarah Zhang.

In the case of conversos, DNA is helping elucidate a story with few historical records. Spain did not allow converts or their recent descendants to go to its colonies, so they traveled secretly under falsified documents. “For obvious reasons, conversos were not eager to identify as conversos,” says David Graizbord, a professor of Judaic studies at the University of Arizona. The designation applied not just to converts but also to their descendants who were always Catholic. It came with more than a whiff of a stigma. “It was to say you come from Jews and you may not be a genuine Christian,” says Graizbord. Conversos who aspired to high offices in the Church or military often tried to fake their ancestry.

The genetic record now suggests that conversos—or people who shared ancestry with them—came to the Americas in disproportionate numbers. For conversos persecuted at home, the fast-growing colonies of the New World may have seemed like an opportunity and an escape. But the Spanish Inquisition reached into the colonies, too. Those found guilty of observing Jewish practices in Mexico, for example, were burned at the stake.

What Do You Know … About Culture?1. DC Comics’ latest superhero flick stars the Game of Thrones actor Jason Momoa as this comic-book character.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. This network, one of the top purveyors of kitschy made-for-TV films, recently released their 2018 holiday feature, titled A Very Nutty Christmas.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. This musician, who has broadcast their struggle with bipolar disorder publicly for more than a year, announced last weekend that they are no longer taking medication in order to bolster creativity.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: Aquaman / Lifetime / Kanye west

Poem of the WeekHere is a portion of “Winter’s Tale” by Maxine Kumin, from our May 2009 issue:

Even from my study at the back

of the house I can hear an orange drop

upstairs, one of the last to grow

on the dwarf tree you bought me

thirty years ago. When it tried

to overtake the window frame

we cruelly lopped side branches and still

it blossomed

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

I’ve had it in my desk drawer for 23 years: a pink plastic pacifier, tucked into a piece of glossy card stock, with a cartoon of a diaper-clad Newt Gingrich brandishing a baby bottle and stomping his foot, and the caption, Now Boarding … Rows 30-35! It’s a treasured artifact of the 1995 government shutdown, when Gingrich confessed he’d forced the closing of the federal government partly because Bill Clinton had relegated him to a rear cabin aboard Air Force One on the way home from Yitzhak Rabin’s funeral in Jerusalem.

Gingrich, then speaker of the House, triggered the shutdown that November by sending Clinton a stopgap spending bill he knew the president wouldn’t sign, because it raised Medicare premiums and cut environmental regulations. Clinton’s veto forced the closure of most of the federal government for six days—ostensibly over a point of principle.

todd s. purdum

todd s. purdumBut Gingrich soon confessed, at a press breakfast sponsored by The Christian Science Monitor, that he had acted partly out of pique, because Clinton had seated him at the rear of the presidential plane and not talked to him on the long flight back from Israel. Moreover, Gingrich was forced to exit via the plane’s rear stairs—with the press and low-level aides.

“This is petty,” the speaker acknowledged. But, he added, “You’ve been on the plane for 25 hours and nobody has talked to you, and they ask you to get off the plane by the back ramp … You just wonder, Where is their sense of manners? Where is their sense of courtesy?” Gingrich acknowledged that his pique at the seeming slight had prompted him to send Clinton a tougher spending bill. “It’s petty,” he said, “but I think it’s human.”

The next day, the New York Daily News ran that cartoon of Gingrich on the front page, with a giant headline: “Cry Baby.” Some Democratic group or other—just which escapes me now—promptly circulated the pacifier card in a gleeful piling on.

[Read: Trump steals a page from Newt Gingrich]

Clinton won the political battle over that shutdown, and a subsequent one a few weeks later. In fact, his tough stance in the standoff helped pave his way to reelection in 1996. But Gingrich had his own sort of revenge: The same day that the speaker complained of his ill treatment, Clinton asked an unpaid intern who was filling in on the skeletal White House staff to join him in his private office. Her name was Monica Lewinsky, and the rest, as they say, is history.

However Donald Trump’s standoff with Senate Democrats ends this week, it seems safe enough to say that there will be consequences no one can now foresee. There almost always are.

We’re ending the year as it began: with the U.S. government headed toward another shutdown, this time chiefly over funding for President Donald Trump’s proposed border wall. Meanwhile, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said he will resign at the end of February, citing disagreements with the president over foreign policy. Mattis is just the latest in a long line of senior administration staff, from John Kelly to Nikki Haley, who announced this year that they are leaving the White House.

Mattis’s resignation comes after Trump’s decision to pull U.S. troops from Syria—a move that did not come as a shock to longtime Syria-policy experts. Mattis, who has always understood Trump’s deficiencies, agreed to serve him out of a sense of patriotism, writes Jeffrey Goldberg, and his departure signals a dangerous third phase of Trump’s foreign policy. But in coverage of Mattis’s resignation, Conor Friedersdorf writes that the news media has failed “to treat the withdrawal of troops [from Syria] as a legitimate, reasonable position.”

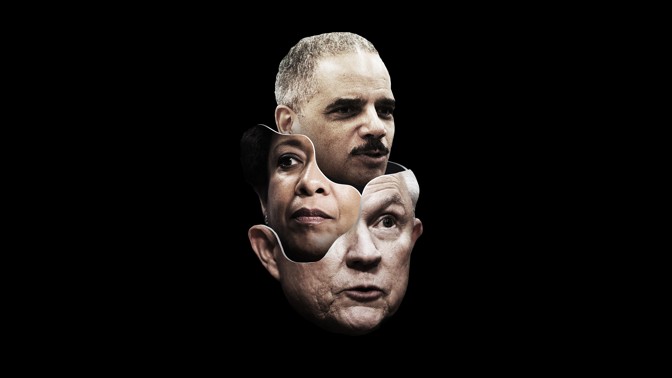

In the final Politics & Policy Daily of 2018, we’re featuring one last round of standout Atlantic politics stories from the past 12 months, including a complex portrait of Heidi Cruz, an assessment of the impact former Attorney General Jeff Sessions has had on the legal gains of the civil-rights era, and an intimate look at the unique weight of grief in the aftermath of the mass shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh.

— Elaine Godfrey, Madeleine Carlisle, and Olivia Paschal

(Matthieu Bourel)

(Matthieu Bourel)The End of Civil Rights

Vann R. Newkirk II

“...from the Black Belt in Alabama in the 1980s to the farthest reaches of the border fence today, the Sessions Doctrine is the endgame of a long legal tradition of undermining minority civil rights.”→ Read on.

The Perpetual Disaster of the Trump Administration

David A. Graham

“It is as though the United States is stumbling, never quite falling on its face but never fully righting itself, either, caught perpetually mid-stumble. The only certainty is more weeks like this one. There is no exit.” → Read on.

The Jews of Pittsburgh Bury Their Dead

Emma Green

“Jewish tradition teaches that the dead cannot be left alone. Some call it a sign of respect for people in death, as in life. Others say that the soul, or nefesh, is connected to the body until it is buried, or even for days afterward, and people must be present as it completes its transition into the next world.”→ Read on.

(Todd Spoth)

(Todd Spoth)Heidi Cruz Didn’t Plan for This

Elaina Plott

“As Heidi had discovered at the beginning of her marriage, signing on to a way of life is one thing; living it is another matter entirely. Despite her best efforts, Real Heidi and Campaign Heidi at times became one.”→ Read on.

The Democrat Who Could Lead Trump’s Impeachment Isn’t Sure It’s Warranted

Russell Berman

“It was Robin Bady, a 67-year-old neighborhood resident, who asked about impeachment: What were the chances, she wondered, that it could happen if Democrats won back the House majority this fall? It’s a question likely on the minds of millions of Americans at the moment, and more than just about anyone else in the country, [Jerry] Nadler is the person to ask.” → Read on.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

On Friday, surgeons in New York removed the lower lobe of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s left lung. According to a statement from the Supreme Court, two nodules—which had been discovered in a CT scan after Ginsburg broke three ribs last month—were determined to be malignant.

Images before the surgery showed no evidence of cancer elsewhere in her body, and doctors at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center reported that there was “no evidence of any remaining disease” after the procedure. According to the statement, no further treatment is planned.

What does this mean?

First, there’s a mandatory caveat in any such circumstance: A prognosis is impossible even for Ginsburg’s doctors to predict perfectly, and very limited information has been made public. Nevertheless, Ginsburg is a public figure whose health status is of particular consequence to American citizens, and readers of the Supreme Court’s statement are likely to draw conclusions. It is possible to add some context to the statement and to determine that this is neither a clean bill of health nor a clear sign of imminent peril.

After the news, I tweeted: “If you’re 85 and you break a rib and get a CT, the radiologist will very likely find pulmonary nodules. Most aren’t removed. Since hers are now out and there’s apparently no evidence of metastatic disease, the primary issue is recovery from the procedure.”

Most readers took this as good news. Though I didn’t mean to imply that she’s cleared. It’s true that nodules are very common—and a nodule is different from a mass, the distinction being the size. A nodule is, by definition, fewer than 3 centimeters (around an inch) in diameter. These two nodules are now gone, and there are apparently no others remaining.

But the word that makes the statement more complicated and concerning is two.

Pulmonary nodules are indeed extremely common, and most are benign. To find two malignant nodules in a person who smokes would not be especially surprising. However, if you have two separate malignant nodules in your lung and you do not smoke, doctors worry that this means they represent metastatic disease from a cancer somewhere else.

This is especially true if the patient has a history of cancer, as Ginsburg does. She had early-stage colon and pancreatic cancers removed in 1999 and 2009, respectively.

Lung nodules are generally removed when they are deemed suspicious for malignancy, meaning they either showed signs of growth or were not seen on prior oncologic screening. “Growing pulmonary nodules can be primary lung cancers, and synchronous ones do appear,” says Howard Forman, a radiologist and professor at Yale. “But in a patient with two primary known malignancies, we would need to know the pathology of the nodules before believing she is cured.”

The pathology report can tell us if the malignant cells are lung cancer—meaning a rare case of two simultaneous new lung cancers in a nonsmoker—or if they represent a recurrence of metastatic colon or pancreatic cancer, or if they are of some other origin. If this is the case, it would raise concern that although current scans showed no evidence of metastatic disease elsewhere, there could be yet-undetectable cancer cells already seeded in Ginsburg’s body.

The fact that the statement says the nodules are indeed malignant means that at least a preliminary pathology report has been done, but this crucial detail—what type of malignancy?—was either unclear or withheld from the statement. It reads only: “According to the thoracic surgeon, Valerie W. Rusch, MD, FACS, both nodules removed during surgery were found to be malignant on initial pathology evaluation.” (I emailed Rusch, who told me, “We have no additional information on the pathology at the present time.”)

“It all depends on the pathology report,” says the pathologist Anirban Maitra, the scientific director of the Ahmed Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research at MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Cancer in the lung is not the same as primary lung cancer, especially in a person with a history of colon and pancreatic cancer. Right now it’s best for the medical community to wait for more details.”

“They might need to run special stains to distinguish lung versus colon versus pancreatic,” Maitra adds. “That could take a couple days and may or may not be conclusive.”

In any case, expect that Ginsburg will be monitored closely in coming years for metastatic disease. In the immediate term, recovery from a lobectomy can be a significant undertaking for an 85-year-old, and that is indeed the relevant health issue for the foreseeable future.

Unlike H. R. McMaster, Rex Tillerson, and Nikki Haley, James Mattis was never going to go quietly. He has read too much history and is too cognizant of his duty for that. His letter of resignation was all the more devastating for its understatement. For more than a year, senior administration officials have constructed the fiction that the United States is following a foreign policy of competing with authoritarian powers. Anyone who has talked with one of these officials in private will be familiar with the mantra—look at the substance of the National Security Strategy, not the tweets. Never mind that the president never spoke of this strategy, even when he made remarks introducing it.

Mattis laid bare the reality. He wrote that his views “on treating allies with respect and also being clear eyed about malign actors and strategic competitors” make it impossible for him to continue to serve the president, because “you have a right to have a Secretary of Defense whose views are more aligned with your views on these and other subjects.”

In a post for Task & Purpose, Paul Szoldra, a former marine, pointed to a speech Mattis delivered in 2014, shortly after he retired from the Marine Corps. He was asked whether there was anything that would lead a four-star general to resign in protest. “You have to be very careful about doing that,” Mattis said. “The lance corporals can’t retire. And they’re going. That’s all there is to it.” He emphasized that he always expected to be heard by policy makers, but not to be obeyed. “My portfolio was narrower than the president’s. He was the commander in chief. He was voted in by the American people.” Be careful, he cautioned, because a leader’s first obligation is to that lance corporal. “You abandon him only under the most dire circumstances, where the message you have to send can be sent no other way. I never confronted that situation.”

That dire situation is now upon us. So what happens next?

[Read: James Mattis’s letter of resignation]

President Donald Trump’s views are well known to anyone who cares to look. In his speeches over the past two years, he has consistently identified four threats to America—immigrants, alliances, trade deficits, and terrorism. (He used to talk a lot about North Korean nuclear weapons, as well, but appears to have since struck a de facto bargain with Kim Jong Un. North Korea has ceased testing missiles and nuclear bombs, and relations between the two countries have warmed.) Over three decades, Trump has consistently expressed admiration for authoritarian leaders, especially in Russia. But above all, Trump wants the freedom to do as he wants, when he wants, free from constraints. He wants to be indulged. He wants to be a king.

The turning point of the Trump administration came on July 17, 2017. For the first six months of his presidency, Trump largely deferred to the so-called axis of adults of Tillerson, McMaster, and Mattis. When he diverged from their advice—when, for example, he refused to endorse Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty while speaking at NATO headquarters—he soon backtracked under pressure. But on July 17 he had had enough. He was sitting through yet another interagency meeting, this time on the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan Of Action. Not only did all of his advisers recommend staying in the deal—the three options in front of him required it. He agreed to effectively extend the deal one more time but demanded that the next time, he be given an option to withdraw.

After that meeting, Trump began to push back. He started giving orders unilaterally—to move the embassy to Jerusalem, to meet with Vladimir Putin, to meet with Kim Jong Un, and even to hold a military parade. But as long as the axis of adults remained in place, he was constrained. So he began to force them out. If there is a common theme behind the reshuffle, it is that Trump replaces independent thinkers with sycophantic loyalists or those too weak to stand up to him. If past practice is any guide, Trump will double down on loyalists when he replaces Mattis. Men such as John Bolton and Mike Pompeo do not agree with Trump on many issues, but they value their loyalty to him personally above their own views and they will never try to thwart his will.

[Read: The Trump administration’s lowest point yet]

Bolton learned this lesson early on. When he became national-security adviser, many observers commented on the irony that his first task would be to implement a policy of diplomatic outreach toward North Korea, something he opposed so vociferously in his previous time in government that President George W. Bush fell out with him over it. Three weeks into the job, Bolton tried to sabotage the talks by claiming that the administration was looking to the Libya model, whereby Muammar Qaddafi unilaterally disarmed. It was apparently intended as a dog whistle that would pass unheard by Trump but that would cause the North Koreans to sink the talks before they began. The North Koreans were furious, as intended. The South Koreans also noticed, though, and complained to Trump. Pompeo backed them up, and Trump was furious. Bolton was excluded from high-level meetings with North Korean officials and was only added to the Singapore summit at the last minute. He learned his lesson—he has not again explicitly worked against the president.

Bolton now focuses on the issues he is interested in and the issues Trump is interested in, but nothing else. Bolton is preoccupied by international law and made opposition to the International Criminal Court and other institutions one of his top priorities. One European diplomat told me that Bolton has spent exponentially more time on dealing with the Western Sahara territorial dispute between Morocco and the Algerian backed Polisario Front—a pet issue of his for decades, given United Nations involvement—than with post-conflict planning for Syria. Days before Trump’s announcement of a retreat from Syria, Bolton briefed European officials that the United States would be staying. Even more significant, Bolton has effectively abolished the interagency process by which major national-security decisions are made in formal consultations with the relevant departments, thus allowing Trump to freelance to his heart’s content.

When Pompeo became secretary of state, he faced a fateful choice: forge an alliance with Mattis, or indulge the president at every turn. He chose the latter course; Trump once remarked that Pompeo is the only person on his team with whom he never fights. This choice trapped Pompeo in a vise. He became secretary when morale was low. He has helped to rebuild the department, but he has dramatically shrunk the role of secretary of state. Foreign diplomats I’ve talked to describe him as the secretary for Iran and North Korea because he works on nothing else. Even on these issues, he will not stand up for himself.

[Jeffrey Goldberg: Mattis always understood Trump’s severe defects]

The president’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria is widely seen as benefiting Tehran. Pompeo, along with Bolton, tried to convince Trump to change his mind, but they folded once he made his decision. Pompeo is particularly wary of opposing. On North Korea, he persists in embracing the myth that a process of denuclearization is underway despite all evidence to the contrary. This puts him in the awkward position of looking foolish and naive. It’s a dangerous place for someone who is so ambitious, which is maybe why he has become so testy in his conversations with journalists when questioned about North Korea.

When Bolton and Pompeo began, they believed that they could persuade Trump to accept them bringing some of the Never Trumpers who opposed the president during the election on to their staff. Those hopes were dashed when Trump rebuked Mike Pence for trying to hire Jon Lerner as his national-security adviser; Lerner had worked for an anti-Trump political-action committee during the campaign. Pence, for his part, has been even quieter than Bolton and Pompeo, refusing to take any stance, even in private, that is at odds with the president. The talent pool has been almost drained dry; there is no untapped reserve of experienced, qualified, Trump-supporting national-security aides. While many people have resigned, other senior officials are remaining in place because they are worried about the real-world consequences of their positions remaining vacant indefinitely, or being filled by someone unqualified.

We are left with a Cabinet that is weak, terrified, and myopic. Meanwhile, the president is empowered and unbound—but also insecure and desperate. Nothing can be ruled out anymore. The president is free to indulge his visceral instincts unchecked. The unilateral declarations on Syria and Afghanistan are just the beginning. It is quite possible that he will try to withdraw U.S. forces from South Korea and Germany, renege on Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, or strike a comprehensive grand bargain with Xi Jinping over the objections of Japan.

It will surely get worse. As the revelations from Robert Mueller’s investigation inflict blow after blow and the subpoenas fly from House Democrats, Trump will become more erratic and dangerous in his decision making. Of all the resignations, the second most damaging after Mattis may be John Kelly. Few liberals shed a tear for him on his departure, but his flaws were largely counterbalanced by one vitally important redeeming feature—he was a stabilizing force on national security. He could check Bolton and channel Mattis. He could play interference. And now he is gone, replaced by Mick Mulvaney, who has no national-security experience.

America’s allies had hoped to ride out the next two years. Senior officials from multiple European and Asian allies told me that they had concluded by mid-2018 that they could engage with the administration but that things went off the rails whenever the president was directly engaged, which was usually on a foreign trip. They decided to deliberately reduce the opportunities for him to be involved. Thus, the 70th anniversary of the NATO summit would not be marked by a leaders’ summit, but would instead occur at the foreign-ministers level (it will be hosted by Pompeo in Washington, D.C.). The agendas for G20 and G7 summits are being pared back, frequently with the support of officials in Washington. But those plans count on an administration that checks Trump, not one that empowers him. It is very possible that America’s adversaries will try to take advantage of the disarray. If Putin or Xi makes a major move, such as trying to test America’s alliances, it will be soon.

With the hollowing out of the Trump administration, the onus now passes to Congress. In her book Troublesome Young Men, Lynne Olson tells the story of Conservative Party rebels in the 1930s who spoke up against their leader and brought Winston Churchill to power. One of the remarkable things about Trump’s first two years is that not a single up-and-coming Republican politician took a stand against the president. Other than John McCain, the only Republicans who did anything are either semi-retired (John Kasich) or retiring (Jeff Flake).

Even leaving morality to one side, that is surprising. Senators such as Tom Cotton see themselves as Trump’s successors, but some might have taken the other side of the bet, especially if they hope to be active in politics for the next two decades. If Trump fails and is discredited, those who paid a price for standing against him will be rewarded. Every defeat and every humiliation will be transformed into a badge of honor. There will be little reward for those who jump on the bandwagon after his fall has become inevitable. Republicans may have increased their majority in the Senate, but this dynamic could be a wild card. As Trump’s troubles deepen, the incentive for younger senators to become troublesome will grow. The confirmation hearings for Mattis’s successor will provide an early test of whether any have grown bold enough to break ranks.

There is a narrative arc to the Trump presidency—a radical, constrained by the system, who breaks out and follows his instincts. The next chapter is predictable. Possessing all the power he ever desired, he will be undone by his own character. All that remains to be seen is how, at what cost, and if his party will do anything to stop it.

On Election Day 2018, Malcolm Kenyatta, a third-generation activist from North Philadelphia, hoped to become a Pennsylvania state representative in the 181st District, which has a 26 percent deep-poverty rate. He made history by becoming the first openly LGBT candidate of color elected to state office in Pennsylvania.

Tim Harris, a friend of Kenyatta’s from college, had followed the activist’s trajectory since graduation. When he heard that Kenyatta was planning to run for Pennsylvania state legislature, Harris knew he had to be there with a camera. His short documentary, Going Forward, depicts Kenyatta’s experience of Election Day, from his 5 a.m. wake-up call to his historic victory as the results are announced late that evening. Along the way, Kenyatta drives around his neighborhood to talk to voters and addresses tough questions about the realities of what he will face in office.

Harris told The Atlantic that he intended to capture “what Election Day is like for a lower-level candidate campaigning in a district that’s desperate for a solution.” Kenyatta has long been an outspoken critic of policies that negatively affect his community. The film makes evident his personal investment in the issues his potential constituents face. “Malcolm actually knows the people in his district,” Harris said. “We could have made a feature out of him saying ‘Hi’ and hugging people.”

While filming, Harris and his team took a fly-on-the-wall approach. “We interviewed Malcolm during the quieter, more introspective moments,” he said.

At one point during the day, Kenyatta catches wind of an adversary who is attempting to discourage people from voting for him due to Kenyatta’s sexuality. Harris said he was pleasantly surprised by the candidate’s reaction. “He didn’t hesitate in wanting to speak with that person, and when he did speak with them, he did it in such a respectful way,” Harris said. “His ability to laugh it off was incredibly admirable.”

“Malcolm basically rejected all forms of negativity while he was campaigning,” Harris added. “Everything was about what he wants to do to improve his community.”

Keyboard art in the Ivory Coast, darts fans in London, a new Boring Company tunnel in California, a coast-guard rescue in Turkey, a terrible fire in Brazil, huge protests in Budapest, a giant Santa in Shanghai, a naturalization ceremony in Los Angeles, and much more

The Atlantic’s readers wrote eloquently and passionately about a wide range of news events, stories, and complicated ideas this year. Here’s a look back at some of what they had to say.

FebruaryAfter the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, Heather Sher, a radiologist who treated some of the victims, wrote about her experience in the emergency room.

“As a doctor,” she wrote, “I feel I have a duty to inform the public of what I have learned … It’s clear to me that AR-15 and other high-velocity weapons, especially when outfitted with a high-capacity magazine, have no place in a civilian’s gun cabinet.”

While not all readers agreed with Sher’s conclusion, many expressed gratitude for her decision to describe what she had seen. “Your thoughts and words were clear, rational, and provided a unique insight into what most of us will not (thankfully) ever see in our lifetime, but will spend days and weeks fearing,” wrote Cindy Pond of Harrodsburg, Kentucky.

MarchThe Munich Security Conference, Eliot Cohen argued in February, was a stark reminder that the global elite have nothing of substance to offer a world in turmoil. Benedikt Franke, the chief operating officer of the Munich Security Conference Foundation, took issue with Cohen’s claim that the conference had lost its way.

“While it may seem petty to get into a quarrel about something as trivial as a policy conference,” Franke wrote to The Atlantic in March, “I believe six of Eliot’s arguments in particular warrant a written response.”

AprilIn April, Sigal Samuel spoke with moral philosophers from around the world about the dilemma of American responsibility in Syria. “What if there is no ethical way to act in Syria now?” she asked. Many ethicists were at a loss.

Readers shared their own answers to that vexing question in their letters. Emily C. Susko of Santa Cruz, California, wrote a poem on the subject. It begins:

And now, now will we go to war?

Is that what we were supposed to have done before?

Overthrow the man who was misbehaving?

Insist we be the ones to do the saving?

Remake the demolished country in our image?

… Did we learn any lessons from the last world-war scrimmage?

Graeme Wood’s “The Refugee Detectives,” published in The Atlantic’s April issue, took readers inside Germany’s high-stakes operation to sort people fleeing death from opportunists and pretenders.

In May, a researcher on refugee flows, a program director at a German political foundation, and the policy director of the International Refugee Assistance Project wrote in to push back on Wood’s framing. “In search of an exciting story, Mr. Wood has left out important facts and nuances, an obfuscation that simplifies and exoticizes refugee narratives and stories in a damaging way,” wrote Ilil Benjamin, the researcher.

Wood responded directly to the critiques: “My article was written to infuriate exactly the class of letter-writer that has responded in tedious triplicate here,” he wrote.

June“Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un shook hands, strode along colonnades, dined on stuffed cucumber and beef short rib confit, and signed a joint statement,” Uri Friedman wrote in June of the two leaders’ meeting in Singapore. It might have been the beginning of something big, Friedman argued, but it started out small.

Nathan King of Madison, Alabama, disagreed. “It is unreasonable to expect anything more than what Mr. Trump got,” he wrote, “so I find it unfair to claim he got very little in return. President Trump (and the world) really want only one thing: the complete denuclearization of North Korea. That will likely take years.”

JulyThe Justice Department announced in July that it was reopening its investigation into the 1955 murder of Emmett Till. Vann R. Newkirk II saw the move as a cynical play. “It’s unclear just what could possibly come out of the case’s reopening,” he wrote.

Dave Tell, the author of the forthcoming book Remembering Emmett Till, replied to Newkirk’s piece with a counterargument. He agreed that it was unlikely that any potential outcomes of a reopened trial would be proportionate to Carolyn Donham’s “admitted role in inciting men to lynch a child in defense of her honor.” But, he wrote, “there are other reasons to welcome the continuing investigation. I’ve written extensively about the commemoration of the Till murder, and one of the many lessons I’ve learned is this: The long-delayed pursuit of justice can spark racial reconciliation in the most unlikely of ways.”

AugustWhen Kofi Annan died in August, Krishnadev Calamur reflected on how the world’s failure in Rwanda had changed the former United Nations secretary-general’s worldview. One reader, D. S. Battistoli of Abenasitonu, Suriname, made a historical argument to lay out what he saw as the UN’s proper role in Rwanda and other conflicts—which is not to prevent genocide.

“It doesn’t seem to me that it can properly be said that the UN failed in, say, Rwanda, any more than it can be said that my hammock failed once again this morning to make my coffee,” Battistoli wrote.

SeptemberIn September, Christine Blasey Ford came forward to allege that the then–Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her when the two were in high school. In the weeks leading up to the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing where both Ford and Kavanaugh testified, Americans once again faced a collective reckoning with the prevalence of sexual assault. The discussion, Megan Garber wrote, asked an insidious question: Is sexual assault simply the way of the world? Caitlin Flanagan wrote a forceful essay about her own high-school experience, titled “I Believe Her.”

In response, readers wrote in with their thoughts about Kavanaugh’s fitness for the Court and the significance of Ford’s story. Some even shared their own stories of assault.

OctoberOn October 5, a jury found the Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke guilty of second-degree murder in the 2014 shooting of Laquan McDonald, who was 17. Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve wrote about the context for Van Dyke’s actions and the guilty verdict. “The city convicted one cop,” she wrote, “but the cop culture that created Van Dyke and others like him is still very much extant. Unless Chicago gets serious about reform, there will be more Laquan McDonalds because there are still Jason Van Dykes.”

In response, Elyse Blennerhassett of Brooklyn, New York, sent in an illustration that she and a friend had made about the case and a letter describing its meaning.

See the drawing and read more here.

NovemberThe shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in November was clear evidence, Franklin Foer argued, that dormant hatreds have reawakened. In the wake of the massacre, he wrote, “any strategy for enhancing the security of American Jewry should involve shunning Trump’s Jewish enablers.”

As readers processed the killings, some reflected on their own Jewishness and their ties to Pittsburgh. “I am a former congregant of Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh,” wrote Stefanie Weiss of New York, New York. “I see many former Squirrel Hillers on Facebook mourning over the loss in our community, and realize that we grew up in such a special place that most of us, no matter how long ago we left, continue to feel like members of this community. We are collectively heartbroken at our loss of innocence.”

DecemberThe recent news that the young Chinese researcher He Jiankui had allegedly made the first CRISPR-edited babies caused an international uproar. Ed Yong outlined the 15 most damning details about the experiment and the circumstances surrounding it. “It is still unclear if He did what he claims to have done,” Yong noted. “Nonetheless, the reaction was swift and negative.”

Atlantic readers echoed that concern. “He overtly violated the Hippocratic oath,” wrote Martha Lynn Coon of Austin, Texas, “that is, first do no harm.”

LOS ANGELES—A cold coming they had of it, T. S. Eliot’s wise men did. I think of that line on crisp, clear December nights in Los Angeles, when the towering, century-old palm trees make our neighborhood seem as if it could pass for the Fertile Crescent, or at least the close-by Paramount Studios backlot where White Christmas was filmed.

Christmas in the Mediterranean climate of Southern California is a surprisingly festive and moving setting for a son of the frozen Midwest. There are no drifting white flakes (unless in the fuzzy form of ash from the devastating seasonal wildfires), but there is a bracing, almost horizontal winter sunlight streaming through the windows.

At the first light of dawn—at dog-walking and kids’ carpool time—the mercury has dipped to the low 40s, and natives are bundled up as if for Nome, while transplants like me parade around in khaki shorts. By noon, the clichés of outdoor living are simple realities, and by dark, a fire is in order in the living-room hearth—abetted by that great California tradition, not a gas log but a gas rod fireplace starter for lighting seasoned oak and pine.

In nearby Beverly Hills, the trunks of the palm trees are wrapped to their chins in miniature white lights, as if they were pearls on the necks in a Modigliani portrait or a debutante’s long white gloves. The Christmas trees for sale on the corner lots—fresh from the Sierras or Oregon—are as green and fragrant as any New England fir. In Marina del Rey, the glittering nighttime boat parade is as enchanting as a Vermont sleigh ride. And, really, where else on Earth could you surf at breakfast, ski at lunch, and still be chilled enough to feel like caroling after dark?

Southern California has all the usual commercial excesses common to modern consumer society, of course. Christmas decorations in retail stores and public spaces go up the morning after Halloween, as they do elsewhere, skipping cruelly over Thanksgiving. The first real rains of the season, lifting oil from long-dry pavement, produce the traffic snarls and accidents of Atlanta in an ice storm. Most poignantly, the homeless people clustered on the sidewalks of Hollywood and in makeshift tent cities under freeway overpasses are sobering reminders that in a place of such overwhelming plenty, there is still no room at the inn for too many Angelenos.

L.A. was the birthplace of the most popular Christmas songs of the 20th century, many of which were written in blistering summer heat (and by Jewish composers). The songwriter Sammy Cahn remembered getting a phone call from his partner Jule Styne during one particularly hot spell, announcing that their client Frank Sinatra wanted a new Christmas song. Cahn objected; how could anything top “White Christmas,” or for that matter, their own “Let It Snow”? Styne persisted: “Frank wants a Christmas song.” So “The Christmas Waltz” was born, “frosted windowpanes” and all.

For me, Los Angeles at Christmas especially evokes that honey-voiced bard of the holiday season, Nat King Cole, who integrated our then-lily-white neighborhood in 1948. His reward? An ugly racial slur burned into his front lawn, or staked on a sign in his yard (sources vary), and poisoned meat tossed into his garden, which killed his dog. In 1948, in California. When he died, in 1965, his funeral was held at St. James on Wilshire, the neighborhood Episcopal parish whose congregation is now a vibrant mix of Korean American, black, and Anglo worshippers—and his name adorns the local Post Office branch in what Eliot might call our “temperate valley.” Goodwill sometimes does win out.

Southern California’s bone-dry air and clear skies helped make it a center of modern American astronomy, and despite climate change and the inevitable air and light pollution of a sprawling megalopolis, it is still possible most nights to see the stars, or at least the lights of slow-moving planes headed for a landing at LAX. And in the age of Emmanuel or the era of Elon Musk, there is hope in the promise of the heavens.

A cold coming they had of it, 2,000 years ago, and a cold coming we so often seem to have of it today. But in the clean winter nights of this bustling, semiarid, overpopulated, hyperkinetic coastal plain, we can still hear the quiet, and see the light.

In 2015 and 2016, Americans faced an alarming statistic: After a couple of decades of overall decline, major data centers reported a sharp uptick of crime in big cities. Donald Trump spoke with dystopian foreboding in his 2016 inaugural address about the “American carnage” wreaking havoc in the country’s metropolises; earlier, at one campaign event, he asserted that “places like Afghanistan” were safer than American cities, where “you get shot walking down the street.”

In the years since, research has painted a much different picture—one that’s uplifting in some ways and dark in others. This week, a pair of crime and mortality reports circling in the news emphasizes that urban violence is decreasing but American cities still face “carnage” of an entirely different sort.

On December 7, the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence released an analysis of recent mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The results included a grim new record for gun violence: 39,773 Americans were killed by guns in 2017, a dramatic increase of more than 1,000 people from the year before. The responses to this report were fraught, with some people pointing to mass shootings as the major culprit, while others were quick to blame “inner-city” violence.

[Read: Americans are dying even younger]

But the murder rates in America’s cities appear to be falling. On Tuesday, the Brennan Center for Justice published an analysis of annual FBI crime data that concluded the murder rate in America’s 30 largest cities dropped 3.1 percent in 2017, and projected a decrease of about 6 percent in 2018. The Brennan Center looks only at data from major cities, but murders in more sparsely populated areas tend to match national trends, says Inimai Chettiar, the director of the Brennan Center’s justice program`

A few cities did see small murder-rate increases, including Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Las Vegas, which owed a 23.5 percent jump to the Mandalay Bay shooting in October 2017. But this broad downturn is more in line with the long-term decline in murder and crime than with the numbers from 2015 and 2016, signaling that those two years could have been blips in the data. “It’s very, very difficult to tell what caused those increases in 2015 and 2016, and what caused them to go back down, or even whether that was a real uptick or whether it was just fluctuation,” says Chettiar.

So now it’s 2018, and though more people are being shot, it seems fewer are being murdered. What gives?

A couple of factors are at play. The big one is suicide. As my colleague Olga Khazan reported in November, the suicide rate in America has gone up 3.7 percent in the past year. A 2017 CDC report found that with little exception, larger percentages of suicides each year are committed with firearms, while methods such as poisoning have increasingly fallen to the wayside. And the agency’s new report makes clear that the majority of people who kill with a gun shoot themselves, not others: Suicides account for 60 percent of the country’s gun deaths.

Suicide can easily be overlooked as a contributor to “gun deaths.” Gun-control measures that make headlines, such as the Trump administration’s move on Tuesday to ban bump stocks, are frequently intended to act as barriers to people seeking to harm others. A study released last year that looked at statewide changes in gun-purchasing laws from 1990 to 2013 found that purchase delays—the period of time between purchasing and receiving a firearm—cut down on the number of firearm suicides by 2 to 5 percent, with no corresponding increase in suicides by other methods. But since the study’s release in March, no states have implemented any major corresponding purchase delays.

Broadly, firearm-related suicide attempts are more common in states with looser gun laws. A person who attempts suicide with a gun is more than twice as likely to end up dead as someone who chooses any other method.

[Read: Why can’t the U.S. treat gun violence as a public-health problem?]

According to Chettiar, a methodological shift among murders, when they do occur, could also be contributing to gun-death data. “When we analyzed the 2016 FBI data, we found that gun violence accounted for almost all of the increase in murders that year—93 percent,” she says. FBI reports show that 73 percent of all homicides were committed with a firearm in 2017. That’s 2 percent more than in 2015, and 4 percent more than in 2013. (Knives are regularly in second place, at about 10 percent.)

What all of this data shows is that while crime may be receding in America’s cities, a different wave of tragedy continues to roll in. Cities have alarmingly high levels of opioid use, a blight that reaches out into suburban and rural areas as well. In 2017, overdose deaths (intentional and accidental) went up by 7 percent, to a record of 70,000—a number higher than deaths from HIV, car crashes, or gun violence at their peaks, as The New York Times points out. Addiction and suicide run hand in hand: Opioid-use disorder is associated with a 40 to 60 percent higher risk of suicidal thoughts. Misusers are 13 times as likely to die of suicide, including by intentional overdose, as nonusers.

Still, opioid-related suicides are only the latest addition to a stunning trend: Regardless of the method or cause, suicide has risen by nearly 30 percent in the United States since 1999. As Americans appear to have decreasingly taken one another’s lives, they’ve increasingly taken their own. There’s a tough road ahead to significant fixes, but without them, America’s death tolls will likely continue to break records.

On a worrisome day in Washington—with a government shutdown looming and the defense secretary resigning—a clip of Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen served as unexpected comic relief. Nielsen, speaking before the House Judiciary Committee on Thursday, responded to a question from Representative Tom Marino by saying, “From Congress I would ask for wall. We need wall.”

"I would ask for wall. We need wall." pic.twitter.com/mkgHZWFgyI

— Josh Marshall (@joshtpm) December 20, 2018Nielsen was, of course, referring to the wall along the southern border with Mexico that President Donald Trump has demanded that Congress fund, precipitating the shutdown threat. When asked by Marino to clarify what she meant by “wall,” she explained that what the administration envisions is really a “wall system,” combining walls, fencing, and various technology.

Nielsen’s plea for “wall”—as opposed to “a wall” or “the wall”—drew torrents of ridicule on Twitter. Oliver Willis of Shareblue Media posted the clip, confirming that it was “an actual quote” from the secretary of homeland security and not from the Incredible Hulk, despite Nielsen’s primitive-sounding “Hulk smash” locution. Besides the Hulk, “We need wall” reminded some of Steve Carell as the low-IQ weatherman Brick Tamland in Anchorman awkwardly declaring “I love lamp.” MSNBC’s Chris Hayes mused, “Did DHS make a style guide change that there’s no definite article before wall?” Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo agreed that this seems like an intentional shift in usage, “but it’s not clear what the point is beyond sounding like you have some kind of focused brain damage.”

[Read: Trump keeps invoking terrorism to get his border wall]

Just last week, DHS was roundly mocked for a press release that used wall in a similar manner. When it was originally published on the department’s website, the release began, “DHS is committed to building wall and building wall quickly.” But just a few days later—after widespread derision on social media—the wording was silently changed so that the opening sentence read, “DHS is committed to building a wall at our southern border and building a wall quickly.”

Despite this editorial tinkering, it’s clear from Nielsen’s testimony that using wall without a preceding article (either the definite the or the indefinite a) is now a standard part of the Trump administration’s language on border security. And it’s fair to wonder whether Trump himself, with the clipped rhetoric he has fashioned both on the stump and on Twitter, is responsible for the stylistic shift.

Consider the evidence. Trump first sounded the alarm about the Mexican border in an all-caps tweet back in August 2014: “SECURE THE BORDER! BUILD A WALL!” Then in April 2015, still two months before he declared his presidential candidacy, Trump said in an interview on Fox News with Bret Baier, “People don’t realize Mexico is not our friend. We have to build the wall.”

[Ieva Jusionyte: What I learned as an EMT at the border wall]

The boiled-down version of “Build the wall” would become an oft-heard chant at Trump rallies, with the same trisyllabic cadence as other crowd favorites including “Drain the swamp” and “Lock her up.” Using a definite article to specify “the wall” served to make Trump’s vague campaign promise sound more concrete, something that his supporters would recognize as shared, common knowledge, appropriate for bumper-sticker sloganeering.

But once “the wall” was established as a Trumpian touchstone, even the definite article could be jettisoned, especially in the limited space of a tweet. On the morning of the Super Tuesday primaries on March 15, 2016, Trump tweeted out his campaign’s core message: “I will bring our jobs back to America, fix our military and take care of our vets, end Common Core and ObamaCare, protect 2nd A, build WALL.” Granted, Trump was running up against what was then a limitation of 140 characters on Twitter, but that “build WALL” closer would become a new kind of signature phrase (even after he could luxuriate in 280 characters when Twitter expanded the limit in November 2017).

Removing definite or indefinite articles in English is associated with terse “headlinese,” which also omits conjunctions and forms of the verb to be. Thus, a news headline might elliptically read “Government facing shutdown” rather than the more fully expressed sentence, “The government is facing a shutdown.” Trump’s tweets sometimes mimic this abbreviated style, especially when he is compressing his rhetorical standbys like “wall”—or, depending on his capitalization whims, “Wall” or “WALL.” Last March, when Trump was wrangling with Congress over how much of an omnibus spending bill would be allocated for border security, his tweets included such lines as “Got $1.6 Billion to start Wall on Southern Border, rest will be forthcoming,” “I had to fight for Military and start of Wall,” and, most cryptically, “Build WALL through M!” (He hit the character limit again, so “M” had to suffice for “Mexico.”)

[Read: A shutdown would be a fitting end to the GOP majority]

In turning “the wall” into “wall,” Trump isn’t simply saving a few characters, though. Forgoing the definite article can also change the syntactic role of wall from a “count noun” to a “mass noun,” as linguists put it. A count noun is, as the name implies, something you can enumerate discretely and express in the singular or plural, while a mass noun is reserved for something that resists differentiation into units, whether it’s an abstraction like fun or luck, or a substance like flour or cement. There was a time in the history of English when wall could more easily be thought of as a mass noun. The Oxford English Dictionary documents usage of wall from around 1600 with a sense of “walling”—that is, the materials that make up a wall, or walls considered collectively. As Politico’s Timothy Noah recalled when he heard Nielsen’s “We need wall,” Shakespeare used wall without an article in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The character Nick Bottom suggests that in the play-within-the-play, an actor should portray a wall through which the lovers whisper: “Some man or other must present Wall.”

Shakespeare aside, for most of its history, wall has been a straightforward count noun. But in the same way that mass nouns can sometimes be converted into count nouns (for a recent example, think of email), count nouns can also get “massified” on occasion. For instance, we tend to think of vote as countable, but in election-night coverage you might hear pundits use it as a mass noun, as in, “We don’t have enough vote to make a call in this race.”

Just as the mass-noun version of vote finds its place in electoral jargon, the massification of wall serves a particular purpose in Nielsen’s bureaucratic discourse, beyond simply emulating her boss.

For Nielsen, using wall as a mass noun makes it easier to talk about proposed structures along the border without committing to a single discrete wall, since whatever they’re planning along the border couldn’t possibly work that way. It is, after all, more of a “wall system” (with “steel slats,” we’re now told). The mass-noun spin on wall should tip off supporters that the border may be more nebulous than they imagined.

Since the start of the Donald Trump administration, a morbid watch has been kept: Though the president is adept at creating his own crises, either intentionally or not, experts noted that he had not faced a full-scale crisis that was not of his own making. Those are the times that test presidents. How would Trump react when his moment came?

It’s fitting that during Advent, the season of waiting before Christmas, a crisis has arrived. But while it is, yet again, Trump’s own creation, it may be just as consequential as the calamity that the president’s critics have long feared. For the past two years, the nation and the administration have stumbled from crisis to crisis, yet the breadth and depth of the current peril might exceed even the period around James Comey’s firing in May 2017 and the aftermath of Trump’s meeting in Helsinki with Russian President Vladimir Putin in July 2018.

Friday dawned with the government heading inexorably toward a shutdown, driven by Trump’s intractable demands for a pricey and likely futile border wall. His administration is in chaos after Defense Secretary James Mattis, the most widely respected figure in the administration, announced his resignation Thursday in a stunning letter. His is only the latest of several high-level departures. Republican leaders are furious over the president’s plans to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria and Afghanistan. Stock markets in the United States and overseas are tumbling. Meanwhile, Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s probe continues to chip away at the foundations of the presidency, gradually compiling an astonishing chronicle of lawlessness and corruption in Trump’s inner circle—with much of Mueller’s work still either incomplete or not public.

[Read: James Mattis’s final protest against the president]

The Mattis resignation has sparked panic in Washington, but the shutdown is, for now, the more urgent crisis. Funding for large portions of the government runs out on Friday. Although Trump bragged last week that he’d be “proud” to shut down the government over Democrats’ refusal to fund his border wall, Congress and the White House on Thursday seemed headed for a quiet stopgap funding measure to keep the government running until February.

But then Trump was seemingly bullied into blowing up the compromise by harsh criticism from his allies in the right-wing media, including Rush Limbaugh, Laura Ingraham, and Breitbart News. The White House announced that he would not sign any bill without wall funding. Neither Trump nor anyone else has any viable plan for bridging the gap, other than hoping that nine Democrats in the Senate will flip and vote for a wall their party despises. Although Trump tweeted Friday morning that “if enough Dems don’t vote, it will be a Democrat Shutdown!” they have little incentive to go along with him, because he has already publicly boasted that he would take the blame.

As the government braced for a closure that could drag into the Christmas holiday, Mattis’s exit arrived unexpectedly. Though the defense secretary, a retired four-star general, had disagreed with Trump repeatedly in the past, his resignation was an astonishing rebuke of the president. Cabinet members seldom resign in protest, and his letter avoided praise for Trump while delivering harsh implicit criticism of the president’s disdain for alliances and affection for authoritarianism.

Mattis’s exit horrified not only Democrats and anti-Trump conservatives, but also some of the president’s closest allies. In what passes for a hair-on-fire reaction by Mitch McConnell standards, the Senate majority leader said, “I am particularly distressed that he is resigning due to sharp differences with the president on these and other key aspects of America’s global leadership.”

Mattis was frequently reckoned to be a crucial brake on Trump’s worst impulses, protecting him from decisions even more disastrous than the ones he made. Whether that was true will likely become clear soon. Yet Mattis resigned because he was unable to dissuade Trump from announcing a precipitous withdrawal of American troops from Syria (in which the president falsely claimed that ISIS was defeated) or stop the president from an expected announcement of a pullout from Afghanistan. These decisions are in keeping with Trump’s campaign promises, but the hasty, nonstrategic methods of withdrawal rattled even critics of both military engagements.

Hawks were even more upset. Senator Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina Republican, lashed out at the announcements and questioned Trump’s choice. “The only reason they’re not dancing in the aisles in Tehran and ISIS camps is they don’t believe in dancing,” he said. While Graham has always favored military intervention, his criticism is notable because he has become a leading stroker of the president’s ego. The matter threatened to drive a spike between Graham and Trump, with the White House adviser Stephen Miller lambasting the senator on CNN Thursday evening.

It’s not just Washington that’s jittery. U.S. stocks fell on Thursday, their second straight day of large losses. While Trump has long boasted about the stock market as an indicator of his economic prowess, the markets have had a bad year. While America fitfully slept, Asian stocks also sank. The poor results have some analysts wondering whether the global economy is headed for a recession, and while presidents have limited control over the economy, at least some of the troubles can be traced to Trump. American stocks fell in reaction to a Federal Reserve interest-rate increase; Trump replaced the more dovish Fed Chair Janet Yellen earlier this year with Jerome Powell, who has proved more eager to hike rates. Meanwhile, Asian markets have been unsettled by Trump’s tariff threats. The president, who shows little real understanding of global trade, does not seem to have grasped that hurting China might drag down U.S. markets, too.

After Mattis’s exit, there will likely be more soon. Chief of Staff John Kelly was once perceived to be among the “adults in the room” (always a dubious moniker), though his reputation was tarnished by errors and Trump sidelined him months ago. Kelly is leaving the White House this month, and Trump, unable to get his top pick as a replacement, has tapped Mick Mulvaney, his chief budget aide, as the acting chief of staff. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke is leaving, chased by a passel of scandals and investigations; Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross might not be far behind.

[Read: The Trump presidency falls apart]

Since Attorney General Jeff Sessions was sacked last month, Matthew Whitaker has been acting in his stead. On Thursday, the Justice Department announced that Whitaker would not recuse himself from overseeing Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. Washington Post reporting revealed that Justice Department ethics officials have said that Whitaker ought to recuse himself, but he overruled the recommendation.

Despite antagonism from Whitaker, Trump, and the attorney-general nominee William Barr, Mueller has been moving quickly and effectively, racking up indictments and guilty pleas rapidly. This week, Trump’s first national-security adviser, Michael Flynn, was in court, but his sentencing was delayed after a federal judge questioned the lenient sentence Mueller’s team had recommended and asked whether Flynn might have committed treason. Mueller is also bearing down on Roger Stone, a longtime Trump associate suspected of serving as a conduit between the Trump campaign and WikiLeaks for the dissemination of emails stolen by Russia.

Despite occasional reports that Mueller is nearly finished with his work, there’s little public evidence that’s the case, and the breadth of the corruption and dishonesty he has exposed in Trump’s inner orbit is already breathtaking. Mueller remains likely the greatest existential threat to Trump, which is one reason the president continues to feverishly attack him at every turn.

The president, who has never appeared to be up to the task of running the country, is acting more erratically and impulsively than ever. “Inside the Oval Office on Thursday, Trump was in what one Republican close to the White House described as ‘a tailspin,’ acting ‘totally irrationally’ and ‘flipping out’ over criticisms in the media,” the Post reported.

Such horrified anonymous quotes are a staple feature of the Trump presidency. They have spilled out in quotes to the press, in books by the authors Michael Wolff and Bob Woodward, and in the infamous anonymous op-ed by a self-proclaimed resister inside the administration. The Mattis resignation letter is surprising because it puts criticisms out in public. It also follows fired Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who earlier this month called Trump “undisciplined” and said the president had repeatedly wanted him to do illegal things.

As a matter of democratic norms, it’s good news when these criticisms come out from behind closed doors—far better than quiet sabotage actions. Yet the fact that Mattis, Tillerson, and others are speaking publicly is a troubling indicator of just how bad things seem to them.

Of course, there have been moments of acute crisis before, even amid the constant stream of crises. In one incredible 10-day stretch in May 2017, Trump fired Comey, disclosed sensitive classified information to Russian officials, threatened Comey, and gave a disastrously incoherent interview to The Economist. That same week, the public learned that Trump had pressured Comey to drop an investigation into Flynn.

In August 2017, Trump reacted sluggishly to white-supremacist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, and insisted that there were “very fine people on both sides.”

In January of this year, Trump grappled with the release of Wolff’s book, botched his own positions on immigration and intelligence policy, referred to African and Latin American nations as “shithole countries,” and canceled a trip to Britain in a fit of pique.

In July, Trump met with Putin in Finland, followed by a bizarre press conference in which he deferred to the Russian leader, sided with Russian denials about electoral interference over the unified conclusions of his own intelligence officials, and mused on allowing Russia to interrogate a former American ambassador to Moscow.

Yet while it is early, this moment seems perhaps even graver. There are fewer guardrails on Trump than ever before, as he replaces experienced and steady hands with more sycophantic ones. The scale of the current crisis is also unusually wide, taking in foreign wars, the global economy, the basic functioning of the federal government, and a major corruption investigation. Nor is this a simple if devilish confluence of related problems. The only common denominator in each of these is the president, a bull in a global china shop. Even if one, or two, or three of these problems could be resolved, it would leave the others. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Friday is the darkest day of the year.

The status quo is unsustainable, and yet it is impossible to predict any breaking point. The criticism that Trump is sustaining from Republicans is scathing. However, GOP leaders harshly criticized Trump after Comey, after Charlottesville, and after Helsinki, but eventually slunk back into alignment with him. Even Graham was back to attacking Democrats for their “hate” of Trump by Thursday night. Perhaps there are real cracks in the Republican wall of begrudging support for Trump, but past experience suggests there’s no reason to expect a true shift. The Democratic takeover of the House in January seems unlikely to solve anything; Congress is already in a stalemate, and the investigations that Democrats have promised will only further inflame Trump.

In January 2018, I wrote that practically everyone understood that the Trump presidency was a disaster: Democrats and Never Trump Republicans, of course, but also his allies, his aides, and even the president himself, who seems deeply unhappy—as he should be, given the direction of his presidency and his country. Yet there was no prospect for any conclusion. Trump shows no sign that he would resign. Democratic leaders remain wary of impeachment, and even if they did pursue it, the Senate would not convict and remove Trump. Invoking the Twenty-Fifth Amendment remains a pipe dream. The only certainty, I wrote, was more crises like that one. And now here we are: another crisis like that one, yet even worse, and still no exit.

You could say that meals—especially holiday meals—are stories in themselves. Beyond the suspense of waiting for a cake to come out of the oven, or the satisfying denouement served in a steaming bowl of soup, there’s a wealth of symbolism (not to mention potential for drama) in gathering to share life-sustaining, life-affirming food. Gustave Flaubert uses turkeys and plum jam to mark the passing years in Madame Bovary’s married life. And Naz Deravian finds a poignant history of Persia in her family’s handed-down recipes.

In Robin Sloan’s novel Sourdough, a disillusioned tech worker struggles to tend to a sourdough starter—and to the human relationships it represents. But the chef Samin Nosrat, who sees food as a way to bring people together, is firm in her belief that those connections are accessible to anyone. And the year’s best recipe books give home cooks the chance to craft their own culinary narrative, even when dining alone.

Each week in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas, and ask you for recommendations of what our list left out. Check out past issues here. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

What We’re Reading

Samin Nosrat wants everybody to cook

“Rather than inundate aspiring cooks with an index of glamorously photographed recipes to follow precisely, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat offers Nosrat’s readers something much more substantial: a cooking philosophy.”

📚 SALT, FAT, ACID, HEAT: MASTERING THE ELEMENTS OF GOOD COOKING, by Samin Nosrat

Writing an Iranian cookbook in an age of anxiety

“As the world thundered, I paved a new, diplomatic relationship with my measuring cups and timer, finding solace in their certainty. Whereas only months before I’d felt restricted by the written recipe, I now relied on it.”

📚 BOTTOM OF THE POT: PERSIAN RECIPES AND STORIES, by Naz Deravian

The strange pathos of the turkey in Madame Bovary

“What does a 19th-century French tragedy, in which a provincial housewife kills herself as a result of her debts and affairs, have to do with an American holiday that celebrates homecoming and overeating? The answer, quite simply, is turkey (along with plum preserve).”

📚 MADAME BOVARY, by Gustave Flaubert

Robin Sloan’s Sourdough is a fascinating riddle

“The starter has survived decades in the brothers’ caring hands—it’s used to make a sourdough bread that’s plated as a side dish to their spicy soup, a fiery broth that, seemingly magically, burns sickness and apathy from its eater. The starter’s survival now depends on a former standout computer-science student from the Midwest.”

📚 SOURDOUGH, by Robin Sloan

The 7 best cookbooks of 2018

“It’s hard not to want to try what’s on any page you turn to … Scanning the streamlined but explicit instructions, you think: easy, quick, works, boom.”

📚 SHAYA: AN ODYSSEY OF FOOD, MY JOURNEY BACK TO ISRAEL, by Alon Shaya, with Tina Antolini

📚 BOTTOM OF THE POT: PERSIAN RECIPES AND STORIES, by Naz Deravian

📚 FEAST: FOOD OF THE ISLAMIC WORLD, by Anissa Helou

📚 SOUL: A CHEF’S CULINARY EVOLUTION IN 150 RECIPES, by Todd Richards

📚 MILK STREET: TUESDAY NIGHTS, by Christopher Kimball

📚 EVERYDAY DORIE: THE WAY I COOK, by Dorie Greenspan

📚 SOLO: A MODERN COOKBOOK FOR A PARTY OF ONE, by Anita Lo

Last week, we asked you to tell us about the books you’ve read that best capture loneliness. Susan Lipman, a reader in Los Angeles, chose John Williams’s Stoner: “It is beautifully written, but its strength is in its ability to tell a story of a man’s life (that many would consider a failure) with dignity and compassion.”

Gitanjali Bhattacharjee recommends The Nowhere Man, by Kamala Markandaya, which “illustrates so many of the tensions that come with being an expatriate of a country that was once colonized by the British, or a child of those expatriates … Reading this book felt at once profoundly lonely as I empathized with Srinivas, the protagonist, and like I had found a necessary community, one for which I’d long been searching.”

What’s a book about food—whether it’s a cookbook with a bigger story behind its recipes, a novel with meals that make your mouth water, or a deep dive into an ingredient’s history—that you think everyone should read? Tweet at us with #TheAtlanticBooksBriefing, or fill out the form here.

This week’s newsletter is written by Rosa Inocencio Smith. The book she loved reading most in 2018 was Her Body and Other Parties, by Carmen Maria Machado.

Comments, questions, typos? Email rosa@theatlantic.com.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.