Teachers and supporters hold signs and umbrellas in the rain during a rally supporting the teachers strike in Los Angeles on Jan. 14, 2019.

Photo: Ringo H.W. Chiu/AP

Almost exactly one year ago today, I sat in a room with a bunch of pissed-off teachers in Mingo County, West Virginia. They were fed up with earning some of the lowest pay in the country, and they were disgusted with how promise after promise had been broken on their health care coverage. They were tired of digging into their own pockets for the supplies they needed, let alone the granola bars, warm jackets, and pairs of shoes that they kept on hand. But more than anything, they were ready to call bullshit. Bullshit on the idea that there was no money for public education, when there was always money when the big-business lobbyists came around looking for tax cuts. Bullshit on the politicians who claimed to care about the future for our kids, when they short-changed them every step of the way. They walked out, and soon their local movement became a state-wide movement that became a national movement. I’ll never forget the day we saw a Kentucky teacher post a picture of a rally sign that read: “Don’t make us go West Virginia on you!”

On Tuesday, I found myself with a whole lot more pissed-off teachers, this time in Los Angeles, California. After trying to negotiate a contract for more than a year, LA teachers have decided to go West Virginia. They decided to stand shoulder to shoulder, hold the line, and shut it down. Because, let’s face it, whether you are the richest county in America or the poorest county, you can bet that your public schools are under siege. Politicians suck the funding out and then blame the teachers for not getting results on their cookie-cutter standardized tests. The wealthy leave or send their kids to private schools. The carcass of the neighborhood school is left for dead at best and actively dismantled at worst.

But there’s a reason why two places as different as Mingo and Los Angeles — not to mention Oklahoma, Arizona, North Carolina, and Colorado — can be part of the same movement. It’s because the attack on public schools is part of a larger national attack on working people. Teachers are on the front lines of this war, and they understand perfectly well what’s at stake. Yes, they are fighting for their own ability to practice their profession without having to also drive an Uber on the side, but what they are really fighting for is the fate of the middle class. The public education system is the bedrock of the American middle class, the great equalizer. Teachers are risking their own livelihoods to try to keep the middle class alive in this country, and we should all be taking up arms.

Think about it. Our schools are the largest investment we make in our children. When the children of the working-class citizen are sent to schools that are overcrowded, unsafe, and falling down, that is a statement of our values, a statement of our priorities. We are saying to the poor, working, and middle classes that we do not think their kids are worth the trouble; they aren’t worth the investment. We’d rather just give another tax cut to Amazon so they can invest in robots, thank you very much. In West Virginia, we watched as there was always money for another tax cut to big energy, but never any to try to pull our schools up from near the worst in the nation. After I retired from the military, I became a teacher at Chapmanville High School and saw firsthand how our kids were getting screwed. You tell me how the American dream is going to be possible for a kid who was taught math by the assistant to the assistant wrestling coach. What a joke. In Los Angeles, the wealthy have already pulled their kids out of the public schools, where 40-plus kids pile into classrooms, and teachers are left to handle everything from broken arms to mental health issues. Charter schools have siphoned millions away from neighborhood schools, and the district absurdly claims that there’s no money for improvements while sitting on a nearly $2 billion surplus.

In Mingo County, the war on the working class is personal. Coal baron Don Blankenship murdered 29 miners through negligence because safety would have hurt his bottom line. He poisoned the water of his own town and built a private water line to his hilltop mansion, but didn’t bother to tell his neighbors that they were drinking coal slurry. Of course, all the local politicians looked the other way. This is cartoonishly evil behavior, and yet the slow poisoning of the working class is playing out in every community in this nation. They are poisoned by the big corporations that treat them as disposable and bust their unions. They are poisoned by politicians who are looking out for their campaign accounts and that big paycheck they will get as a lobbyist when they finish “serving.” They are poisoned by the contempt of those who believe that you are only worthy of a life of dignity if you live in the right place, look a certain way, have a certain size bank account, and can score high enough on your math SATs.

The teachers in West Virginia, LA, Oklahoma, Arizona, Kentucky, Colorado, and more are saying something radical with their actions. They are saying that every single child of this nation is worthy. The poor kids. The immigrant kids. The special needs kids. The holler kids. They all deserve a safe place, with dedicated professionals. A place to thrive. A place to explore. A place to be treated as the human beings they are, rather than a problem to be dealt with or another faceless name on an overstuffed roster.

Underfunding, privatizing, demonizing teachers, these are all tactics used to destroy a public education system that helped to build the middle class. I often say that the elites of this nation better take care, because if we get to a place in this country where there’s only the dirt poor and the filthy rich, the dirt poor will eat the filthy rich. The teachers strikes are a warning shot.

Don’t make us go West Virginia on you.

The post Richard Ojeda on the LA Teachers Strike: “Don’t Make Us Go West Virginia on You” appeared first on The Intercept.

Em novembro passado, os franceses deram início a uma nova tradição de sábado: manifestantes “gilet jaune” vestindo coletes de segurança amarelos começaram a sair às ruas às dezenas de milhares pela manhã, gritando slogans contra o alto custo de vida, contra o presidente francês, Emmanuel Macron, e contra seus impostos e reformas de serviço social.

À tarde, os manifestantes entravam em confronto com a polícia de choque, que disparava várias rodadas de gás lacrimogêneo e lançava granadas de efeito moral para dispersá-los. Ao anoitecer, os manifestantes quebravam vidros de estações de ônibus e lojas e às vezes incendiavam carros antes de fugir quando os policiais chegavam. E do meio da noite até a manhã, os outros “gilets jaunes” – limpadores de rua, muitas vezes imigrantes, que também usam os coletes de segurança – limpavam a bagunça.

Neste último sábado, cerca de 8 mil manifestantes compareceram ao “9º Ato”, ou 9ª semana, de protestos, marchando de Bercy, no leste de Paris, até o Arco do Triunfo, a oeste da cidade, na tentativa de chegar a Champs-Elysées. Pelo menos 85 mil pessoas se reuniram em toda a França, marcando a segunda semana consecutiva em que o comparecimento aos protestos dos coletes amarelos aumentou após diminuir durante as festas de fim de ano. “Estou aqui porque sou mãe solteira e trabalho há 20 anos”, explicou Stephanie, uma funcionária do setor público de 40 anos que marchou em Paris. “Depois de pagar minhas contas no final do mês, não consigo nem levar minha filha ao cinema”, disse ela.

Fotos: Joe Penney para o Intercept

A força e a resistência do movimento, que não tem estrutura fixa, nenhuma liderança clara e nenhuma afiliação política ou institucional, surpreenderam a todos, inclusive a Macron. Desde o primeiro protesto, em 17 de novembro, as manifestações dos “gilet jaune” corroeram a capacidade da Macron de realizar reformas planejadas para os impostos e os serviços sociais e prejudicaram seriamente sua imagem pública. Os protestos representam a maior ameaça à popularidade do presidente, sua capacidade de governar e ao liberalismo europeu de centro do qual ele se tornou o porta-voz global na era Trump. No entanto, embora a potência dos protestos dos coletes amarelos seja inegável, o perigo é que a extrema direita possa sair vitoriosa na batalha quanto à identidade política do movimento.

Macron subiu ao poder contornando partidos políticos estabelecidos. Seu partido La République en Marche foi criado em 2016 e conquistou a maioria dos assentos no parlamento apenas um ano depois, tomando o lugar dos partidos tradicionais das forças gastas de esquerda e direita. Isso significa que os dois principais partidos da oposição na política francesa são agora o Reunião Nacional de extrema direita de Marine Le Pen e a extrema esquerda da França Insubmissa. Ambos têm mais a ganhar com o colapso do centro. Embora Le Pen não tenha feito muitos comentários públicos sobre os protestos, o apoio ao seu partido subiu para o topo das pesquisas para as próximas eleições parlamentares europeias, com 35%. Por outro lado, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, o líder da França Insubmissa, cortejou agressivamente os manifestantes, mas caiu nas pesquisas, sugerindo que o movimento dos coletes amarelos, que é mais popular em áreas mais rurais onde o apoio de extrema direita é alto, é mais uma vantagem para Le Pen do que qualquer outro político.

A batalha pelos “gilets jaunes” e o enfraquecido centro francês têm grandes consequências para os partidos populistas à esquerda e à direita em toda a Europa. Trabalhadores e políticos em todo o continente estão apresentando suas reivindicações. O ministro do interior e o vice-primeiro-ministro italianos elogiaram os manifestantes, e os meios de comunicação russos, como o Russia Today e o Sputnik News, deram a eles ampla cobertura. Protestos de coletes amarelos brotaram na Bélgica, Croácia, Irlanda e na Holanda. Grupos de extrema direita no Reino Unido tentaram se apropriar do movimento para si e marcharam em Londres, no sábado.

Foto: Joe Penney para o Intercept

O primeiro protesto “gilet jaune” foi lançado no Facebook como uma resposta a um imposto sobre o carbono que elevou o preço do diesel, uma grande fonte de frustração para as pessoas que vivem em regiões não atendidas pelo transporte público. O movimento escolheu o colete de segurança amarelo, obrigatório em todos os veículos de estrada, como seu símbolo, e contou com o apoio de simpatizantes de Marine Le Pen, cujos objetivos declarados incluíam o “Frexit” – a saída da França da União Europeia – e a interrupção da imigração. À medida que o movimento crescia, sua base se diversificava, e seus objetivos, também. “Nós pensamos que era um movimento instrumentalizado pela extrema direita”, disse o apoiador de colete amarelo Abdel Moula Elakramine, trabalhador de armazém de 52 anos e pai de três filhos que também é membro do França Insubmissa em Bobigny, um subúrbio parisiense. “Não é verdade. Os pobres estão na extrema direita, na extrema esquerda… estão em toda parte!”

A maioria dos grandes protestos na França é convocada por sindicatos ou partidos políticos. Mas uma série de duras perdas para os sindicatos contra a Loi du Travail, uma lei de reforma trabalhista que flexibilizou as condições para demitir trabalhadores, bem como uma greve dos trabalhadores ferroviários contra a liberalização da companhia ferroviária nacional, deixou pouca fé nessas resistências institucionais. Em ambos os casos, as batalhas de meses de duração dos sindicatos não provocaram nenhuma mudança nas posições do governo.

Os “gilets jaunes” são únicos em sua total rejeição de qualquer afiliação do tipo. O mais próximo que têm de porta-vozes são os administradores de conhecidas páginas do Facebook, como o motorista de caminhão Eric Drouet, de 33 anos, e Maxime Nicolle, de 31 anos, bem como Priscilla Ludosky, de 33 anos, que lançou uma petição contra o imposto sobre o diesel no site change.org que conta com mais de um milhão de assinaturas. Os manifestantes são marcados pela ambiguidade: qualquer um pode ser um “gilet jaune”, e você pode vestir e tirar seu colete a qualquer momento.

Manifestantes de coletes amarelos entram em confronto com a polícia de choque em Paris, em 12 de janeiro de 2019.

Joe Penney para o Intercept

Essa ambiguidade permitiu uma participação mais aberta de pessoas que não estavam envolvidas em nenhum movimento de protesto e torna menos previsível e difícil o controle e a negociação por parte do governo. Isso também significa, no entanto, que não há ninguém para reivindicar a responsabilidade e disciplinar os colegas manifestantes quando espancam jornalistas, fazem gestos antissemitas ou assediam motoristas negros. As teorias da conspiração são abundantes nos grupos de coletes amarelos no Facebook, e elas costumam incluir referências ao antigo empregador de Macron, o Grupo Rothschild – um código para antissemitismo. Explosões de racismo e a composição predominantemente branca dos manifestantes afastaram ativistas negros de participar.

Os protestos dos coletes amarelos também são únicos na intensidade da violência, tanto dos manifestantes quanto da polícia. Pelo menos 10 pessoas morreram durante protestos, a maioria atropelada por carros e caminhões enquanto bloqueavam a estrada. Em dezembro, manifestantes construíram barricadas e incendiaram dezenas de carros e motos na rua. Durante a edição de 5 de janeiro, manifestantes utilizaram uma empilhadeira para arrombar a porta do escritório do porta-voz de Macron, Benjamin Griveaux, forçando-o a fugir pela entrada dos fundos, enquanto um ex-pugilista profissional foi filmado socando e chutando um gendarme. Alguns relatórios afirmam que o Macron está preocupado com sua segurança pessoal. Manifestantes tentaram atravessar fileiras policiais que estavam guardando a casa do presidente em Touquet, em dezembro, e a família de sua esposa expressou preocupação de que a loja de chocolates que administram em sua cidade natal, Amiens, seja atacada.

As forças de segurança muitas vezes responderam aos protestos com muita força. Pelo menos uma dúzia de pessoas perdeu a visão em um olho depois de ser atingido por granadas de efeito moral ou bombas de gás lacrimogêneo e mais de 80 pessoas ficaram gravemente feridas, segundo o site CheckNews.fr. Uma mulher de 80 anos morreu em Marselha depois de ser atingida no rosto por uma bomba de gás lacrimogêneo. No último sábado, vi a polícia em Paris mirando em manifestantes em vez de no ar ou no chão. Eu mesmo fui atingido por uma bomba de gás lacrimogêneo na coxa enquanto não estava na multidão, levando-me a acreditar que foi intencional. Estava carregando duas câmeras e usando um capacete claramente marcado como “IMPRENSA” e fotografava manifestantes em uma área com poucas pessoas ao redor.

Foto: Joe Penney para o Intercept

A brutalidade policial fez com que mais franceses brancos tivessem contato com o que as pessoas não brancas experimentam regularmente, argumentou Almamy Kanouté, organizador do comitê de Justiça para Adama Traoré, criado após a morte do negro de 24 anos Adama Traoré em custódia policial. “Foram necessárias algumas pessoas recebendo bolas de borracha no rosto, espancadas com cassetetes, atingidas por gás e abusadas sem ter cometido um ato de incivilidade para que se vissem na experiência de pessoas excluídas e não brancas em geral”, explicou ele.

O medo de ser alvo de brutalidade policial também contribuiu para que alguns ativistas negros e outros ativistas não brancos se demonstrassem reticentes em participar. Laurent Lalanne, assistente social do subúrbio de Bobigny, disse que, se os manifestantes negros “fossem a uma revolta assim e fossem na frente, nós seríamos os primeiros alvos”. Lalanne, no entanto, apoia o movimento, porque está lutando por serviços sociais.

Laurent Lallane usa um colete amarelo em sua casa no subúrbio parisiense de Bobigny, na França, em 11 de janeiro de 2018, para demonstrar solidariedade aos manifestantes, em 11 de janeiro de 2019.

Foto: Joe Penney para o Intercept

Os protestos tiveram um impacto enorme na economia também. O país perdeu milhões de euros em veículos danificados, fachadas de lojas e muito mais, enquanto as horas extras dos policiais dispararam e os voos internacionais para Paris diminuíram de 5 a 10% em dezembro. As perturbações causadas pelos protestos fizeram 58 mil trabalhadores serem demitidos, temporariamente suspensos ou terem suas horas reduzidas, de acordo com o ministro do trabalho francês Muriel Pénicaud. O governo gastou 32 milhões de euros para pagá-los durante o desemprego, de acordo com uma disposição das leis trabalhistas francesas.

Em seu primeiro ano e meio no cargo, Macron aprovou sua agenda liberal recusando-se a negociar com sindicatos e insultou publicamente as pessoas empobrecidas várias vezes, inclusive dizendo a um jovem desempregado que tudo do que ele precisava fazer para conseguir um emprego era “atravessar a rua”. É, portanto, irônico que os coletes amarelos tenham utilizado algumas das táticas de Macron – contornando as vias tradicionais de resistência, tornando-se mais formidável do que qualquer outro movimento social.

Manifestante de colete amarelo carrega uma bandeira francesa com as palavras “Macron mata” escritas, em Paris, em 12 de janeiro de 2019.

Foto: Joe Penney para o Intercept

A resposta de Macron à crise foi revogar o imposto sobre o diesel e prometer uma série de outras reformas, incluindo o aumento do salário mínimo em 100 euros por mês. Mas os críticos expressaram ceticismo sobre seus planos para implementar as prometidas mudanças, e Macron tentou assumir o controle da narrativa, pedindo um “debate nacional” de um mês sobre as principais questões de governança a partir desta semana. O debate contará com fóruns abertos à população em todo o país, embora não haja garantia de implementação de qualquer política.

Enquanto isso, os manifestantes estão se preparando para o próximo sábado.

Tradução: Cássia Zanon

The post Na 10ª semana de protestos, Macron segue sem respostas para os ‘coletes amarelos’ appeared first on The Intercept.

Trabalhei por sete anos como investigador da Polícia Civil de São Paulo. Quando ingressei, eu fazia o primeiro ano da faculdade de Direito, quer dizer, tentava, pois estava prestes a trancar o curso por absoluta falta de dinheiro. Não faltava comida porque tinha uma bolsa alimentação que me permitia comer no restaurante universitário duas vezes ao dia. Mas não tinha teto: morava de favor na república de amigos, dormia no chão, sobre um edredom. Logo que fui aprovado, minha renda subiu para R$ 1,1 mil e virei patrão – passei a comer quatro vezes ao dia e ter uma cama. Daí vem minha primeira gratidão à Polícia.

Os medos de alguém que anda desarmado não são nada perto daqueles de quem anda armado.Da pessoa que eu era antes de andar armado e autorizado pelo Estado a invadir a vida do cidadão comum, quase nada sobrou. Essa transformação é a segunda bênção que recebi da corporação. Hoje, com o distanciamento necessário, percebo como os medos de alguém que anda desarmado não são nada perto daqueles de quem anda armado.

Não importa o lado da lei que o sujeito está. Seja quem utiliza a arma para se defender ou para roubar, o peso do aço não é só físico. Ele te marca, de alguma forma, para a vida toda porque foi fabricada para uma única e exclusiva função: matar. Todo policial conhece a regra, evite sacar a arma. Nunca a saque, se possível for. Mas se sacou, é para matar.

É sinal de inocência acreditar que o criminoso vá refugar ao se ver diante da boca do cano. Normalmente quem está no crime não tem nada a perder, nem mesmo a vida, que já lhe foi subtraída pela miséria. Nas ruas, o policial experiente sabe que, naquele átimo de tempo que antecede o disparo, o clique no gatilho não pode esperar pela misericórdia. Se não o fizer, acreditando que a simples presença de sua arma em punho convencerá o sujeito a desistir, ele próprio estará no destino de outro projétil.

O resultado do ato não é tão breve como essa decisão. Entre ser investigado em um inquérito, processado e julgado pelos sete do tribunal do júri, talvez o pior seja carregar a marca de “assassino” pelo resto da vida na folha de antecedentes. Indelével. O peso da arma sempre vai te lembrar o peso do cadáver que você fez nascer. Quando perceber, estará rodeado de mortos na lembrança. Não importa que sua responsabilidade seja somente sobre aquele primeiro. Todos os cadáveres são leais com seus pares.

Dois cidadãos de bem e suas armasEnquanto eu estava na polícia, a atual Lei do Desarmamento ainda não estava em vigor. Posse e porte sem autorização legal eram tratados como sinônimos pelo Estado, sem distinção das gravidades das condutas. Embora já não fosse mera contravenção, na virada no milênio ela se tornou um delito de menor potencial ofensivo, cuja pena, em regra, não ultrapassava o pagamento de uma cesta básica. Era mais fácil comprar um trinta e oito cano curto do que um Chevette.

Os ocupantes de toda sorte de ofícios pretensamente “arriscados” estavam autorizados a comprá-las. Em um caso da época, um gerente de banco estava sendo investigado por disparos de arma de fogo. Segundo o histórico do boletim de ocorrência, irritado com a balbúrdia de crianças que jogavam bola em frente a sua casa, ele as ofendeu e as ameaçou.

O pai de uma delas não gostou da reprimenda. Ao ir tirar satisfações no portão da residência, o averiguado, dessa vez já armado, apareceu no quintal e efetuou de três a cinco tiros para o alto. A arma nunca foi encontrada, e o inquérito foi arquivado por ausência de provas. Segundo relatou durante o interrogatório, ela tinha sido furtada de dentro de sua casa há muito tempo.

O dono do animal morto não quis registro formal, por medo de que o próximo disparo fosse contra alguém da família.Um senhor, que em seus tempos de glória havia sido fiscal de quarteirão, matou o cachorro do vizinho com apenas um tiro de 9mm. Ao atender pessoalmente a ocorrência, encontrei o bichinho com uma perfuração certeira entre os olhos e outra na barriga (esta última talvez tenha sido por onde o projétil saiu).

O dono do animal não quis nenhum registro formal, por medo de que o próximo disparo fosse contra alguém da família. Só nos acionou para garantir que não houvesse mais atentados naquela madrugada. Preferiu mudar-se de endereço com esposa e filhos.

Mesmo assim eu ousei abrir o boletim de ocorrência, mas a família negou a causa mortis do animal. Eu tentei convencer o delegado a me deixar solicitar uma mandado de busca para ser cumprido na casa do velho (por lei é ele quem está autorizado a entrar com o pedido no Judiciário; na prática, quem elabora o pedido é a pessoa que investiga, e não quem assina), mas virei chacota do DP quando sugeri a exumação do cadáver para comprovar o tipo do ferimento.

Por terem esses dois casos relativas repercussões no bairro, em São Paulo, ambas as casas foram alvo de ladrões. E, como o destino sempre me foi inclinado a sofisticadas reviravoltas, fui escalado para atendê-los. O gerente do banco listou o roubo de um televisor de 29 polegadas, máquina de escrever, alguns dólares e outros objetos que não me recordo.

Perguntei sobre a arma, ele desconversou, repetindo para mim que ela já havia sido roubada há alguns anos, mas não quis registrar o crime por falta de tempo. Como eu já não era mais um recrutinha, menti desonestamente:

— Fique tranquilo com os objetos. Nós já sabemos quem é o ladrão (disse aqui um apelido aterrorizante). E eu tenho uma pessoal desavença com esse vagabundo. Só vou terminar esse BO para ir até o barraco dele e prendê-lo. Aí ele vai nos dizer tudo o que levou do senhor, para quem vendeu, e estejam onde estiverem, eu vou recuperá-los (não houve mesóclises e todas as conjugações no plural, mas quero me lembrar assim).

Pude ver o estado de choque do homem e todo o raciocínio que criou: se ele continuasse com aquela historinha ou, se resolvesse me contar a verdade e no futuro o ladrão viesse a me dizer que tinha encontrado a arma naquela casa e naquele dia, ficaria provado que ele havia mentido para o Ministério Público e Judiciário, no processo anterior.

Já o velho, como não tinha nada registrado contra ele, foi objetivo: “levaram minha arma”. Apenas a arma, uma querida 765. Seu relato era tenro, descrevia as características da pistola com nítida saudade.

Viúvo, não via os filhos há anos. Arrombaram a janela da cozinha e com a mesma objetividade que agora me contava, ordenaram que entregasse o ferro. Só foi convencido após algumas coronhadas na boca, provadas com a parte superior da dentadura que trazia em pedaços em uma das mãos.

O homicídio é um crime democráticoAinda tenho contato com mortes provocadas pelas armas dos cidadãos de bem. Como atualmente trabalho no Tribunal do Júri de São Paulo, vejo milhares de inquéritos que versam sobre homicídios ocorridos no trânsito. Nestes, são raros são os casos em que se descobre o autor dos disparos.

Mais comum ainda são as mortes ocorridas na intimidade dos lares. O homicídio é um crime democrático, qualquer um pode cometer. O pai de família cumpridor de seus deveres com a pátria, a criança curiosa, a tiazinha do Rivotril. Basta um momento de extremo estresse e ter o azar de encontrar uma arma de fogo ao alcance. Não precisa nem fazer mira. Basta apontar e… pou! O destino cumprirá sua promessa.

Permita-se discutir, brigar, ao lado de um revólver, e a desgraçada sorte de uma tragédia estará composta.O calibre é sempre o mesmo, qualquer um do rol permitido pela legislação. Já o matador, quando é preso, segue uma regra: é um amador. Gostaria de vivenciar a realidade dos grandes criminosos sanguinários, assassinos por profissão, porém, esses se matam entre si, em uma legislação que se apresenta mais eficaz do que a do Estado, e a despeito dela. Mas, infelizmente, o acaso é uma triste realidade na vida do homem. Permita-se discutir, brigar, ao lado de um revólver, e a desgraçada sorte de uma tragédia estará composta.

Eu não prendi o ladrão das casas que lhes contei. Foi outro colega. Como ele conhecia a piada que corria a meu respeito, me chamou para conhecer o rapaz. Jovem, não mais velho do que eu. Perguntei onde estavam as armas, ele não quis dizer. Essa informação seria arrancada pela equipe que o investigou, e a ética policial me fez aprender que não era da minha conta o método que usariam. Só perguntei por falta de assunto. E a máquina de escrever?

— Não tinha máquina de escrever não, senhor. Eu só queria as armas. Nada é mais valioso no mundo do crime do que um tiozinho moscando com uma arma dentro de casa.

The post ‘Nada é mais valioso no crime do que um tiozinho moscando com uma arma dentro de casa’ appeared first on The Intercept.

The Center for American Progress fired two staffers suspected of being involved in leaking an email exchange that staffers thought reflected improper influence by the United Arab Emirates within the think tank, according to three sources with knowledge of the shake-up. Both staffers were investigated for leaking the contents of an internal email exchange to The Intercept, but neither of the former employees was The Intercept’s source.

“He is a consummate team player who will raise whatever concerns he has through proper channels, but at the end of the day, he’s on board with the team.”One of those fired, Ken Gude, was a senior national security staffer. He worked at CAP since 2003 and previously served as the progressive think tank’s chief of staff. The notion that he would have leaked the exchange just doesn’t square with his time at CAP, said one of the sources close to the situation. “Ken loves CAP and has dedicated 15 years of his life to the organization,” said the source. “He is a consummate team player who will raise whatever concerns he has through proper channels, but at the end of the day, he’s on board with the team.”

A CAP spokesperson acknowledged two employees were fired as a result of the leak investigation, but said that the leak was not the reason they were fired: “We are not going to discuss internal personnel matters, but no one was fired at CAP for leaking or whistleblowing.” Internally, however, multiple members of CAP leadership have used the leak as the leading rationale for the firings in multiple settings, sources said. Gude did not return requests for comment.

At issue was an internal debate over how to frame CAP’s response to the murder of Washington Post contributing columnist Jamal Khashoggi, who was dismembered by Saudi Arabian officials inside the nation’s consulate in Istanbul on October 2.

The initial draft of the CAP’s statement condemned the killing and Saudi Arabia’s role in it, calling for specific consequences. Brian Katulis, a Gulf expert at CAP, objected to the specific consequences proposed in an email exchange with other national security staffers, according to sources who described the contents of the thread to The Intercept. At an impasse, the specifics were dropped, replaced merely with a call to “take additional steps to reassess” the U.S.-Saudi relationship, and the statement was released to the public on October 12.

“The alleged detention, torture, and murder of U.S. resident and journalist Jamal Khashoggi by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a heinous and reprehensible act that deserves global condemnation. The Trump administration should hold the Saudi government accountable,” the shortened statement said. “In a welcome response, members of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee have moved to hold Saudi Arabia accountable under the Global Magnitsky Act. The administration and Congress should take additional steps to reassess the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia to determine whether it continues to reflect our long-term interests.”

The UAE, Saudi Arabia’s closest ally, is one of the top donors to the think tank. Katulis is close with the UAE’s ambassador in Washington, Yousef Al Otaiba, who is the go-between for Emirati money flowing into Washington. Otaiba also played a key role in elevating Mohammed bin Salman to his position as crown prince of Saudi Arabia, using his considerable influence within the American foreign policy establishment to make the case for bin Salman’s moderation and reform-minded approach to government.

Katulis is CAP’s link to Otaiba. As The Intercept has previously reported, Katulis worked with the diplomat to help organize UAE-sponsored trips to the wealthy Gulf country for American think tank experts, according to emails purloined from Otaiba’s Hotmail inbox. They were released to the media by a group called Global Leaks amid a row between the UAE and its neighborhood rival Qatar. According to the emails, Katulis has also given Otaiba advice on how to lobby the Trump administration on issues relating to Egypt.

The CAP email exchange about Khashoggi’s killing was not leaked to The Intercept by a CAP staffer; its substance was described by a source outside CAP. The exchange was subsequently confirmed by another source within CAP who reviewed it, but who is not on the national security team and was not included on the original chain. At no time during the reporting of the Intercept story did either Intercept journalist working on it receive any information from the CAP employees identified in the leak investigation.

The Intercept learned of the email exchange while reporting a December 23, 2018, story about the role of establishment progressive groups in the legislative fight to end the Yemen war. The Intercept’s request for comment on that story prompted an internal leak investigation at CAP, which included searching employees’ emails without their knowledge.

After the leak investigation, the staffers were fired before the article was published, according to three sources with knowledge of the chronology. The sources declined to speak on the record, as doing so could jeopardize professional relationships.

Gude, according to his Twitter timeline, was on paternity leave at the time of his firing. He has since removed CAP from his Twitter bio. Attempts to reach the second staffer have been unsuccessful, but a source who first confirmed the firing requested that we not publish the staffer’s name so as to protect the former staffer’s future employment prospects. Multiple sources subsequently confirmed the staffer’s termination.

The second employee was suspected of leaking, according to one source, because the staffer forwarded the exchange to a superior, concerned about the propriety of the debate around the Khashoggi statement. But the now-fired employee had no intention of making the matter public, according to the source.

The accounts of the email exchange on Khashoggi were not included in the December 23 Intercept article.

“I cannot overstate how widely known this was.”The dispute over the statement was widely discussed within CAP, and people outside the organization also learned of it. “I cannot overstate how widely known this was,” said one of The Intercept’s sources about the email exchange. CAP’s acceptance of UAE money has also been controversial within the organization for some time.

The UAE operated torture chambers in Yemen “in which the victim is tied to a spit like a roast and spun in a circle of fire,” the Associated Press has reported.

Gude has criticized U.S. policymakers for ignoring the UAE’s human rights abuses, an article that CAP itself pointed to when defending its record on the war in Yemen to The Intercept. “In United Arab Emirates (UAE)-controlled prisons, Yemeni detainees are stripped naked, tied up, have large rocks suspended from their testicles, and raped or sodomized by wooden or steel poles. All of it is filmed by guards,” Gude wrote, in perhaps CAP’s most graphic summary to date of the reports of UAE torture. “These are some of the gruesome details in a new report from The Associated Press (AP)—a follow-up to its June 2017 report—documenting the horrific torture and abuse occurring in UAE-run prisons in Yemen.”

The irony of Gude’s firing is that he celebrated the statement on Twitter the day it was released. “Great statement,” Gude wrote on Twitter, “demanding the US hold Saudi Arabia accountable for the murder of Jamal #Khashoggi & MBS’s increasingly reckless actions that have killed thousands of Yemenis & jailed women’s rights advocates.”

The post Amid Internal Investigation Over Leaks to Media, the Center for American Progress Fires Two Staffers appeared first on The Intercept.

To say that the United Kingdom’s system of democratic governance is showing signs of strain, the day after Prime Minister Theresa May’s proposed deal to exit the European Union was rejected by Parliament in an unprecedented landslide, would be a considerable understatement.

That’s because the massive vote against May’s compromise Brexit plan — by a coalition of members of Parliament who want a more radical break from the EU and those who want to remain closer to, or even inside, the trading bloc — reveals that something far closer to a systemic meltdown is already in progress.

The core of the problem is that the country’s representative democracy, in which decisions are traditionally taken by a government acting on behalf of a majority of Parliament’s members, was thrown into crisis in 2016, when the public voted in a referendum to withdraw from the EU, despite the fact that most legislators, including May herself, had argued against a British exit. It didn’t help that the pro-Brexit campaign succeeded in large part because of exaggerations and outright lies about how painless a divorce from the EU would be.

The prime minister has also ignored the fact that, as pro-EU voters continue to point out, the vote in favor of Brexit was a narrow one — the measure passed by a 52-48 margin.

? Ooof, bit of a Brexit ding-dong pic.twitter.com/oZQ4qY6Uw8

— BBC Wales News (@BBCWalesNews) January 15, 2019

While she has steadfastly refused to say that she thinks Brexit is actually a good idea, May has committed her government to carrying out what she describes as the will of the people to leave the EU, but also worked to limit the inevitable economic damage of cutting ties with her nation’s leading trade partners.

But now that May’s compromise deal with the EU has been rejected by 230 votes, and there appears to be no majority in Parliament for any other version of Brexit, the political system seems to have arrived at an impasse, just 10 weeks before the country’s membership in the union expires on March 29.

The parliamentary gridlock, and a lack of clear options for how to proceed in a country without a written constitution or any rules or procedures for how to implement a referendum result that most of the people’s elected representatives see as profoundly damaging, has prompted calls for a second referendum in some quarters, inchoate rage in others, and a wave of bleakly comic commentary online.

I don't want to confuse you with technical language about the Brexit vote but basically nobody knows what the fuck happens now.

— Karl Sharro (@KarlreMarks) January 15, 2019

Now, more than ever before, Britain needs The Day Today to tell us that "Everything's alright, it's okay" pic.twitter.com/eKFRgkSIl6

— CuriousBritishTelly (@CuriousUkTelly) January 13, 2019

Before the Brexit referendum introduced an element of direct democracy into the parliamentary system, a prime minister who lost a vote on the central issue of her government by even one vote, let alone 230, would have been expected to resign or call a general election. The leader of the opposition Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, has attempted to force May to step down by calling for a vote of no confidence in her government on Wednesday, but she is widely expected to win the vote and remain in office, since even her staunchest opponents in the Conservative Party, and her Ulster unionist allies, fear a Corbyn-led government more than they hate May.

As the clock ticks down, and May scrambles to come up with a revised Brexit plan before the country crashes out with no deal — a possibility described in near-apocalyptic terms, since it would likely result in all air traffic being halted, massive traffic jams around ports, shortages of food and medicine, and the collapse of the country’s manufacturing industry — a contentious debate over a possible second referendum has prompted real fears of political violence from a fringe of extreme nationalist Brexit supporters.

In recent weeks, members of May’s Conservative Party who want a closer relationship with Europe or a second referendum, like Nick Boles and Anna Soubry, have been subjected to death threats and verbal abuse by far-right activists in yellow vests and MAGA hats on the streets around Parliament.

Today someone called and promised to burn my house down. What ever next? The ducking stool?

— Nick Boles MP (@NickBoles) January 15, 2019

Is this what its come to …? @Anna_Soubry faces "nazi" taunts….. pic.twitter.com/NHNMULtbEK

— norman smith (@BBCNormanS) January 7, 2019

After the thugs chanted Nazi at Anna Soubry while she was on BBC, I went to check on her. But she had company… pic.twitter.com/II7nIdqMoF

— Femi (@Femi_Sorry) January 7, 2019

A leader of the far-right mob, James Goddard, has also been filmed recently hurling abuse at Owen Jones, a Guardian columnist and Labour supporter, and screaming that a brown-skinned police officer who interrupted his harassment was “fair game” and “ain’t even fucking British.”

Just met some lovely Tommy Robinson fans and I’d love for you to get to know them too pic.twitter.com/iRom8GavNy

— Owen Jones? (@OwenJones84) January 7, 2019

Here's footage of Far Right 'Yellow Vest' leader James Goddard telling people (police?) they're 'fair game' and threatening 'war'. When is enough going to be enough? When someone's hurt? Killed? (via @dunc_saboteur) pic.twitter.com/yUkjCZSPHT

— Mike Stuchbery?? (@MikeStuchbery_) January 7, 2019

While the unruly mobs on the streets are generally small, some members of May’s government have argued that it is essential to honor the result of the 2016 referendum to avoid fueling that sort of rage. Supporters of a second referendum, like the former BBC journalist Gavin Esler, are not persuaded.

It’s fascinating how the argument for Brexit has changed from “sunlit uplands” and “Brexit dividends” to “do Brexit or the neo Nazis will get angry.” Is that the best this brain dead government can come up with? Appeasement didn’t work before and won’t work now. https://t.co/RnvuLkGArj

— Gavin Esler (@gavinesler) January 12, 2019

While polling shows growing support for a second referendum, as the country tires of a focus on Brexit that all but blots out other concerns, and the costs of leaving the EU have become more clear, May is steadfastly opposed to another vote. That means legislation mandating a new referendum would have to be embraced by Corbyn, who fears alienating the significant minority of Labour voters who support Brexit to please the larger number that wants to stop it.

Still, if no other solution is found to the impasse, a new referendum could offer a way out for the deadlocked Parliament. Although a result different from that of 2016 is far from certain, recent calculations by the pollster Peter Kellner suggest that the country gets more pro-EU with each passing day. As Kellner wrote in September, while older Britons voted for Brexit in the 2016 referendum by 2-to-1, more than a million people have died since the vote, and nearly 2 million younger citizens who were not eligible to vote then are now. Among those new voters, polling by Kellner’s former firm, YouGov, suggests that 87 percent of those new voters would support staying in the EU if they had a chance to vote.

As a result of older Britons dying and younger ones reaching voting age, Kellner calculated that the Leave majority has been shrinking by over 1,350 votes a day, so that even if nobody changed their vote, by this Friday, January 19, there could be more people of voting age opposed to Brexit than in support of it.

“This means that by March 29, it will be difficult to sustain the argument that the settled view of the British electorate is that Brexit should take place,” Kellner observed. “We are told that we should ‘respect the verdict of the people,’ and not reopen the decision they — we — reached in 2016. The latest research shows that this depends not only on the proposition that voters cannot change their minds, but on a specific definition of ‘the people.’ It includes those who have died since the referendum — and excludes almost two million new voters who were too young in 2016 but will be old enough to vote by next March.”

Correction: January 16, 2019, 10:54 a.m.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly described Owen Jones as a supporter of a second referendum.

The post British Democracy Nears Meltdown as Parliament Deadlocks Over Brexit appeared first on The Intercept.

Subscribe to the Intercepted podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, Radio Public, and other platforms. New to podcasting? Click here.

Donald Trump has shaken the national security establishment to its core with his pledge to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria and Afghanistan. This week on Intercepted: Trump says he wants to end U.S. wars abroad, while he threatens to use emergency powers to further militarize U.S. immigration enforcement. On Twitter, Trump advocates isolationism, while embracing lifelong warmongers like John Bolton and Benjamin Netanyahu. Investigative reporter and historian Gareth Porter analyzes Trump’s pledge to pull troops from Syria and Afghanistan. He breaks down why Israel and the Pentagon don’t want to see an end to U.S. militarism. Historian Greg Grandin lays out the nativist roots of the U.S. Border Patrol, its connection to CIA dirty wars in Latin America, and nearly 100 years of brutality and impunity. Sudan has been rocked by large demonstrations for the past month, threatening the regime of Omar al-Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court. Despite Bashir’s pariah status, Trump has lifted some longstanding sanctions against his regime. Journalist Hana Baba discusses her recent trip to Sudan and what the protests are really about.

Transcript coming soon.

The post One Wall, Supersized, Extra Racism, Hold the Wars appeared first on The Intercept.

On January 20, 2017, Donald Trump stood on the steps of the Capitol, raised his right hand, and solemnly swore to faithfully execute the office of president of the United States and, to the best of his ability, to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. He has not kept that promise.

Instead, he has mounted a concerted challenge to the separation of powers, to the rule of law, and to the civil liberties enshrined in our founding documents. He has purposefully inflamed America’s divisions. He has set himself against the American idea, the principle that all of us—of every race, gender, and creed—are created equal.

This is not a partisan judgment. Many of the president’s fiercest critics have emerged from within his own party. Even officials and observers who support his policies are appalled by his pronouncements, and those who have the most firsthand experience of governance are also the most alarmed by how Trump is governing.

“The damage inflicted by President Trump’s naïveté, egotism, false equivalence, and sympathy for autocrats is difficult to calculate,” the late senator and former Republican presidential nominee John McCain lamented last summer. “The president has not risen to the mantle of the office,” the GOP’s other recent nominee, the former governor and now senator Mitt Romney, wrote in January.

The oath of office is a president’s promise to subordinate his private desires to the public interest, to serve the nation as a whole rather than any faction within it. Trump displays no evidence that he understands these obligations. To the contrary, he has routinely privileged his self-interest above the responsibilities of the presidency. He has failed to disclose or divest himself from his extensive financial interests, instead using the platform of the presidency to promote them. This has encouraged a wide array of actors, domestic and foreign, to seek to influence his decisions by funneling cash to properties such as Mar-a-Lago (the “Winter White House,” as Trump has branded it) and his hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue. Courts are now considering whether some of those payments violate the Constitution.

More troubling still, Trump has demanded that public officials put their loyalty to him ahead of their duty to the public. On his first full day in office, he ordered his press secretary to lie about the size of his inaugural crowd. He never forgave his first attorney general for failing to shut down investigations into possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia, and ultimately forced his resignation. “I need loyalty. I expect loyalty,” Trump told his first FBI director, and then fired him when he refused to pledge it.

Trump has evinced little respect for the rule of law, attempting to have the Department of Justice launch criminal probes into his critics and political adversaries. He has repeatedly attacked both Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Special Counsel Robert Mueller. His efforts to mislead, impede, and shut down Mueller’s investigation have now led the special counsel to consider whether the president obstructed justice.

As for the liberties guaranteed by the Constitution, Trump has repeatedly trampled upon them. He pledged to ban entry to the United States on the basis of religion, and did his best to follow through. He has attacked the press as the “enemy of the people” and barred critical outlets and reporters from attending his events. He has assailed black protesters. He has called for his critics in private industry to be fired from their jobs. He has falsely alleged that America’s electoral system is subject to massive fraud, impugning election results with which he disagrees as irredeemably tainted. Elected officials of both parties have repeatedly condemned such statements, which has only spurred the president to repeat them.

These actions are, in sum, an attack on the very foundations of America’s constitutional democracy.

The electorate passes judgment on its presidents and their shortcomings every four years. But the Framers were concerned that a president could abuse his authority in ways that would undermine the democratic process and that could not wait to be addressed. So they created a mechanism for considering whether a president is subverting the rule of law or pursuing his own self-interest at the expense of the general welfare—in short, whether his continued tenure in office poses a threat to the republic. This mechanism is impeachment.

Trump’s actions during his first two years in office clearly meet, and exceed, the criteria to trigger this fail-safe. But the United States has grown wary of impeachment. The history of its application is widely misunderstood, leading Americans to mistake it for a dangerous threat to the constitutional order.

That is precisely backwards. It is absurd to suggest that the Constitution would delineate a mechanism too potent to ever actually be employed. Impeachment, in fact, is a vital protection against the dangers a president like Trump poses. And, crucially, many of its benefits—to the political health of the country, to the stability of the constitutional system—accrue irrespective of its ultimate result. Impeachment is a process, not an outcome, a rule-bound procedure for investigating a president, considering evidence, formulating charges, and deciding whether to continue on to trial.

The fight over whether Trump should be removed from office is already raging, and distorting everything it touches. Activists are radicalizing in opposition to a president they regard as dangerous. Within the government, unelected bureaucrats who believe the president is acting unlawfully are disregarding his orders, or working to subvert his agenda. By denying the debate its proper outlet, Congress has succeeded only in intensifying its pressures. And by declining to tackle the question head-on, it has deprived itself of its primary means of reining in the chief executive.

With a newly seated Democratic majority, the House of Representatives can no longer dodge its constitutional duty. It must immediately open a formal impeachment inquiry into President Trump, and bring the debate out of the court of public opinion and into Congress, where it belongs.

Democrats picked up 40 seats in the House of Representatives in the 2018 elections. Despite this clear rebuke of Trump—and despite all that is publicly known about his offenses—party elders remain reluctant to impeach him. Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the House, has argued that it’s too early to talk about impeachment. Many Democrats avoided discussing the idea on the campaign trail, preferring to focus on health care. When, on the first day of the 116th Congress, a freshman representative declared her intent to impeach Trump and punctuated her comments with an obscenity, she was chastised by members of the old guard—not just for how she raised the issue, but for raising it at all.

In no small part, this trepidation is due to the fact that the last effort to remove an American president from office ended in political fiasco. When the House impeached Bill Clinton, in 1998, his popularity soared; in the Senate, even some Republicans voted against convicting him of the charges.

Pelosi and her antediluvian leadership team served in Congress during those fights two decades ago, and they seem determined not to repeat their rivals’ mistakes. Polling has shown significant support for impeachment over the course of Trump’s tenure, but the most favorable polls still indicate that it lacks majority support. To move against Trump now, Democrats seem to believe, would only strengthen the president’s hand. Better to wait for public opinion to turn decisively against him and then use impeachment to ratify that view. This is the received wisdom on impeachment, the overlearned lesson of the Clinton years: House Republicans got out ahead of public opinion, and turned a president beset by scandal into a sympathetic figure.

Instead, Democrats intend to be a thorn in Trump’s side. House committees will conduct hearings into a wide range of issues, calling administration officials to testify under oath. They will issue subpoenas and demand documents, emails, and other information. The chair of the Ways and Means Committee has the power to request Trump’s elusive tax returns from the IRS and, with the House’s approval, make them public.

Other institutions are already acting as brakes on the Trump presidency. To the president’s vocal frustration, federal judges have repeatedly enjoined his executive orders. Robert Mueller’s investigation has brought convictions of, or plea deals from, key figures in his campaign as well as his administration. Some Democrats are clearly hoping that if they stall for long enough, Mueller will deliver them from Trump, obviating the need to act themselves.

But Congress can’t outsource its responsibilities to federal prosecutors. No one knows when Mueller’s report will arrive, what form it will take, or what it will say. Even if Mueller alleges criminal misconduct on the part of the president, under Justice Department guidelines, a sitting president cannot be indicted. Nor will the host of congressional hearings fulfill that branch’s obligations. The view they will offer of his conduct will be both limited and scattershot, focused on discrete acts. Only by authorizing a dedicated impeachment inquiry can the House begin to assemble disparate allegations into a coherent picture, forcing lawmakers to consider both whether specific charges are true and whether the president’s abuses of his power justify his removal.

Waiting also presents dangers. With every passing day, Trump further undermines our national commitment to America’s ideals. And impeachment is a long process. Typically, the House first votes to open an investigation—the hearings would likely take months—then votes again to present charges to the Senate. By delaying the start of the process, in the hope that even clearer evidence will be produced by Mueller or some other source, lawmakers are delaying its eventual conclusion. Better to forge ahead, weighing what is already known and incorporating additional material as it becomes available.

Critics of impeachment insist that it would diminish the presidency, creating an executive who serves at the sufferance of Congress. But defenders of executive prerogatives should be the first to recognize that the presidency has more to gain than to lose from Trump’s impeachment. After a century in which the office accumulated awesome power, Trump has done more to weaken executive authority than any recent president. The judiciary now regards Trump’s orders with a jaundiced eye, creating precedents that will constrain his successors. His own political appointees boast to reporters, or brag in anonymous op-eds, that they routinely work to counter his policies. Congress is contemplating actions on trade and defense that will hem in the president. His opponents repeatedly aim at the man but hit the office.

Democrats’ fear—that impeachment will backfire on them—is likewise unfounded. The mistake Republicans made in impeaching Bill Clinton wasn’t a matter of timing. They identified real and troubling misconduct—then applied the wrong remedy to fix it. Clinton’s acts disgraced the presidency, and his lies under oath and efforts to obstruct the investigation may well have been crimes. The question that determines whether an act is impeachable, though, is whether it endangers American democracy. As a House Judiciary Committee staff report put it in 1974, in the midst of the Watergate investigation: “The purpose of impeachment is not personal punishment; its function is primarily to maintain constitutional government.” Impeachable offenses, it found, included “undermining the integrity of office, disregard of constitutional duties and oath of office, arrogation of power, abuse of the governmental process, adverse impact on the system of government.”

Trump’s bipartisan critics are not merely arguing that he has lied or dishonored the presidency. The most serious allegations against him ultimately rest on the charge that he is attacking the bedrock of American democracy. That is the situation impeachment was devised to address.

Video: It’s Time to Impeach TrumpAfter the House impeaches a president, the Constitution requires a two-thirds majority in the Senate to remove him from office. Opponents of impeachment point out that, despite the greater severity of the prospective charges against Trump, there is little reason to believe the Senate is more likely to remove him than it was to remove Clinton. Indeed, the Senate’s Republican majority has shown little will to break with the president—though that may change. The process of impeachment itself is likely to shift public opinion, both by highlighting what’s already known and by bringing new evidence to light. If Trump’s support among Republican voters erodes, his support in the Senate may do the same. One lesson of Richard Nixon’s impeachment is that when legislators conclude a presidency is doomed, they can switch allegiances in the blink of an eye.

But this sort of vote-counting, in any case, misunderstands the point of impeachment. The question of whether impeachment is justified should not be confused with the question of whether it is likely to succeed in removing a president from office. The country will benefit greatly regardless of how the Senate ultimately votes. Even if the impeachment of Donald Trump fails to produce a conviction in the Senate, it can safeguard the constitutional order from a president who seeks to undermine it. The protections of the process alone are formidable. They come in five distinct forms.

The first is that once an impeachment inquiry begins, the president loses control of the public conversation. Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton each discovered this, much to their chagrin. Johnson, the irascible Tennessee Democrat who succeeded to the presidency in 1865 upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, quickly found himself at odds with the Republican Congress. He shattered precedents by delivering a series of inflammatory addresses that dominated the headlines and forced his opponents into a reactive posture. The launching of impeachment inquiries changed that. Day after day, Congress held hearings. Day after day, newspapers splashed the proceedings across their front pages. Instead of focusing on Johnson’s fearmongering, the press turned its attention to the president’s missteps, to the infighting within his administration, and to all the things that congressional investigators believed he had done wrong.

It isn’t just the coverage that changes. When presidents face the prospect of impeachment, they tend to discover a previously unsuspected capacity for restraint and compromise, at least in public. They know that their words can be used against them, so they fume in private. Johnson’s calls for the hanging of his political opponents yielded quickly to promises to defer to their judgment on the key questions of the day. Nixon raged to his aides, but tried to show a different face to the country. “Dignity, command, faith, head high, no fear, build a new spirit,” he told himself. Clinton sent bare-knuckled proxies to the television-news shows, but he and his staff chose their own words carefully.

Trump is easily the most pugilistic president since Johnson; he’s never going to behave with decorous restraint. But if impeachment proceedings begin, his staff will surely redouble its efforts to curtail his tweeting, his lawyers will counsel silence, and his allies on Capitol Hill will beg for whatever civility he can muster. His ability to sidestep scandal by changing the subject—perhaps his greatest political skill—will diminish.

As Trump fights for his political survival, that struggle will overwhelm other concerns. This is the second benefit of impeachment: It paralyzes a wayward president’s ability to advance the undemocratic elements of his agenda. Some of Trump’s policies are popular, and others are widely reviled. Some of his challenges to settled orthodoxies were long overdue, and others have proved ill-advised. These are ordinary features of our politics and are best dealt with through ordinary electoral processes. It is, rather, the extraordinary elements of Trump’s presidency that merit the use of impeachment to forestall their success: his subversion of the rule of law, attacks on constitutional liberties, and advancement of his own interests at the public’s expense.

The Mueller probe as well as hearings convened by the House and Senate Intelligence Committees have already hobbled the Trump administration to some degree. It will face even more scrutiny from a Democratic House. White House aides will have to hire personal lawyers; senior officials will spend their afternoons preparing testimony. But impeachment would raise the scrutiny to an entirely different level.

In part, this is because of the enormous amount of attention impeachment proceedings garner. But mostly, the scrutiny stems from the stakes of the process. The most a president generally has to fear from congressional hearings is embarrassment; there is always an aide to take the fall. Impeachment puts his own job on the line, and demands every hour of his day. The rarest commodity in any White House is time, that of the president and his top advisers. When it’s spent watching live hearings or meeting with lawyers, the administration’s agenda suffers. This is the irony of congressional leaders’ counseling patience, urging members to simply wait Trump out and use the levers of legislative power instead of moving ahead with impeachment. There may be no more effective way to run out the clock on an administration than to tie it up with impeachment hearings.

As Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton each discovered, once an impeachment inquiry begins, the president loses control of the public conversation. (Everett Historical; Charles Tasnadi; J. Scott Applewhite / AP)

As Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton each discovered, once an impeachment inquiry begins, the president loses control of the public conversation. (Everett Historical; Charles Tasnadi; J. Scott Applewhite / AP)But the advantages of impeachment are not merely tactical. The third benefit is its utility as a tool of discovery and discernment. At the moment, it is often hard to tell the difference between wild-eyed conspiracy theories and straight narrations of the day’s news. Some of what is alleged about Trump is plainly false; much of it might be true, but lacks supporting evidence; and many of the best-documented claims are quickly forgotten, lost in the din of fresh allegations. This is what passes for due process in the court of public opinion.

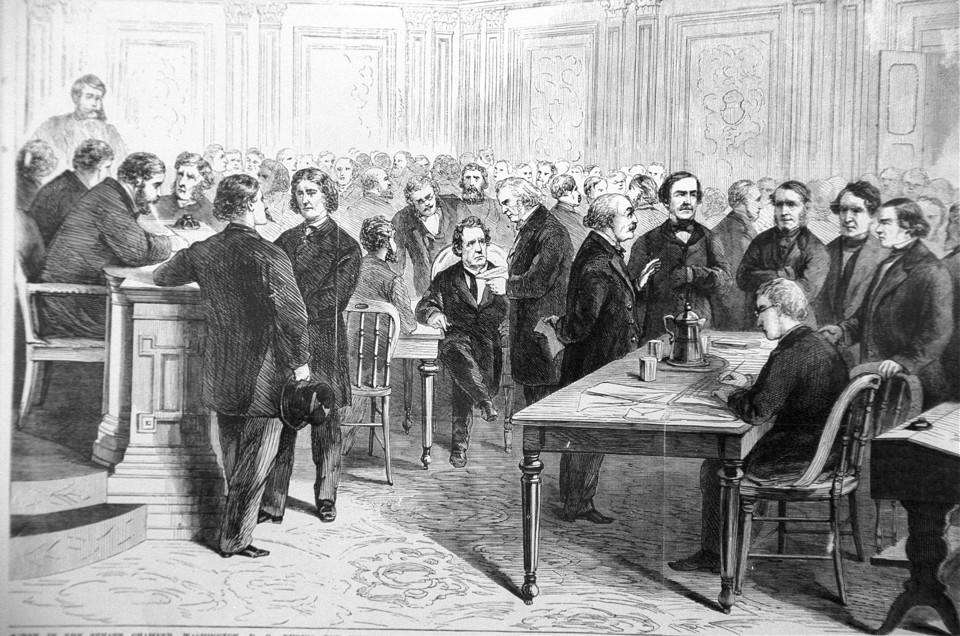

The problem is not new. When Congress first opened the Johnson impeachment hearings, for instance, the committee spent two months chasing rumor and innuendo. It heard allegations that Johnson had sent a secret letter to former Confederate President Jefferson Davis; that he had associated with a “disreputable woman” and, through her, sold pardons; that he had transferred ownership of confiscated railroads as political favors; even that he had conspired with John Wilkes Booth to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. The congressman who made that last claim was forced to admit to the committee pursuing impeachment that what he possessed “was not that kind of evidence which would satisfy the great mass of men”—he had simply based the accusation on his belief that every vice president who succeeds to the highest office murders his predecessor.

There was public value, though, in these investigations. The charges had already been leveled; they were circulating and shaping public opinion. Spread by a highly polarized, partisan press, they could not be dispelled or disproved. But once Congress initiated the process of impeachment, the charges had to be substantiated. And that meant taking them from the realm of rhetoric into the province of fact. Many of the claims against Johnson failed to survive the journey. Those that did eventually helped form the basis for his impeachment. Separating them out was crucial.

The process of impeachment can also surface evidence. The House Judiciary Committee began its impeachment hearings against Nixon in October 1973, well before the president’s complicity in the Watergate cover-up was clear. In April 1974, as part of those hearings, the Judiciary Committee subpoenaed 42 White House tapes. In response, Nixon released transcripts of the tapes that were so obviously expurgated that a district judge approved a subpoena from the special prosecutor for the tapes themselves. That demand, in turn, eventually produced the so-called smoking-gun tape, a recording of Nixon authorizing the CIA to shut down the FBI’s investigation into Watergate. The evidence that drove Nixon from office thus emerged as a consequence of the impeachment hearings; it did not spark them. The only way for the House to find out what Trump has actually done, and whether his conduct warrants removal, is to start asking.

That is not to say that impeachment hearings against Trump would be sober and orderly. The Clinton hearings were something of a circus, and the past two years on Capitol Hill suggest that any Trump hearings will be far worse. The president’s stalwart defenders are already attacking the integrity of potential witnesses and airing their own conspiracy theories; an attempt to smear Mueller with sexual-misconduct claims collapsed spectacularly in October. His accusers, meanwhile, hurl epithets and invective. In Congress, Trump’s most committed detractors might be tempted to follow the bad example of the Clinton impeachment, when, instead of conducting extensive hearings to weigh potential charges, House Republicans short-circuited the process—taking the independent counsel’s conclusions, rushing them to the floor, and voting to impeach in a lame-duck session. Trump’s opponents need to put their faith in the process, empowering a committee to consider specific charges, weigh the available evidence, and decide whether to proceed.

Hosting that debate in Congress yields a fourth benefit: defusing the potential for an explosion of political violence. This is a rationale for impeachment first offered at the Constitutional Convention, in 1787. “What was the practice before this in cases where the chief Magistrate rendered himself obnoxious?” Benjamin Franklin asked his fellow delegates. “Why, recourse was had to assassination in wch. he was not only deprived of his life but of the opportunity of vindicating his character.” A system without a mechanism for removing the chief executive, he argued, offered an invitation to violence. Just as the courts took the impulse toward vigilante justice and safely channeled it into the protections of the legal system, impeachment took the impulse toward political violence and safely channeled it into Congress.

Nixon’s presidency was marked by an upsurge in political terrorism. In just its first 16 months, 4,330 bombings claimed 43 lives. As the Vietnam War wound down and the militant left began to lose its salience, it made opposition to the president its new rallying cry. “Impeach Nixon and jail him for his major crimes,” the Weather Underground demanded in its manifesto, Prairie Fire, in July 1974. “Nixon merits the people’s justice.” But that seemingly radical demand, intended to expose the inadequacy of the regular constitutional order, ironically proved the opposite point. By the end of the month, the House Judiciary Committee had approved three articles of impeachment; in early August, Nixon resigned. The ship of state, it turned out, had the capacity to right itself. The Weather Underground continued its slide into irrelevance, and political violence eventually receded.

The current moment is different, of course. Today, the left is again radicalizing, but the overwhelming majority of political violence is committed by the far right, albeit on a considerably smaller scale than in the Nixon era. Trump himself has warned that “the people would revolt” if he were impeached, a warning that echoes earlier eras. When Congress debated impeachment in 1868, some likewise predicted that it would provoke Andrew Johnson’s most ardent supporters to violence. “We are evidently on the eve of a revolution that may, should an appeal be taken to arms, be more bloody than that inaugurated by the firing on Fort Sumter,” warned The Boston Post.

The predictions were wrong then, as Trump’s are likely wrong now. The public understood that once the impeachment process began, the real action would take place in Congress, and not in the streets. Johnson knew that inciting his supporters to violence would erode congressional support just when he needed it most. That seems the most probable outcome today as well. If impeached, Trump would lose the luxury of venting his resentments before friendly crowds, stirring their anger. His audience, by political necessity, would become a few dozen senators in Washington.

And what if the Senate does not convict Trump? The fifth benefit of impeachment is that, even when it fails to remove a president, it severely damages his political prospects. Johnson, abandoned by Republicans and rejected by Democrats, did not run for a second term. Nixon resigned, and Gerald Ford, his successor, lost his bid for reelection. Clinton weathered the process and finished out his second term, but despite his personal popularity, he left an electorate hungering for change. “Many, including Al Gore, think that the impeachment cost Gore the election,” Paul Rosenzweig, a former senior member of Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s team, told me. “So it has consequences and resonates outside the narrow four corners of impeachment.” If Congress were to impeach Trump, whatever short-term surge he might enjoy as supporters rallied to his defense, his long-term political fate would likely be sealed.

In these five ways—shifting the public’s attention to the president’s debilities, tipping the balance of power away from him, skimming off the froth of conspiratorial thinking, moving the fight to a rule-bound forum, and dealing lasting damage to his political prospects—the impeachment process has succeeded in the past. In fact, it’s the very efficacy of these past efforts that should give Congress pause; it’s a process that should be triggered only when a president’s betrayal of his basic duties requires it. But Trump’s conduct clearly meets that threshold. The only question is whether Congress will act.

Here is how impeachment would work in practice. The Constitution lays out the process clearly, and two centuries of precedent will guide Congress in its work. The House possesses the sole power of impeachment—a procedure analogous to an indictment. Traditionally, this has meant tapping a committee to summon witnesses, subpoena documents, hold hearings, and consider the evidence. The committee can then propose specific articles of impeachment to the full House. If a simple majority approves the charges, they are forwarded to the Senate. The chief justice of the United States presides over the trial; members of the House are designated to act as “managers,” or prosecuting attorneys. If two-thirds of the senators who are present vote to convict, the president is removed from office; if vote falls short, he is not.

Although the process is fairly clear, the Founders left us only vague instructions about when to implement it. The Constitution offers a short, cryptic list of the offenses that merit the impeachment and removal of federal officials: “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The first two items are comparatively straightforward. The Constitution elsewhere specifies that treason against the United States consists “only in levying War” against the country or in giving the country’s enemies “Aid and Comfort.” As proof, it requires either the testimony of two witnesses or confession in open court. Despite the appalling looseness with which the charge of treason has been bandied about by members of Congress past and present, no federal official—much less a president—has ever been impeached for it. (Even the darkest theories of Trump’s alleged collusion with Russia seem unlikely to meet the Constitution’s strict definition of that crime.) Bribery, similarly, has been alleged only once, and against a judge, not a president.

It is the third item on the list—“high crimes and misdemeanors”—on which all presidential impeachments have hinged. If the House begins impeachment proceedings against Donald Trump, the charges will depend on this clause, but Congress will first need to decide what it means.

At the Constitutional Convention, an early draft included “treason, bribery, and corruption,” but it was shorn of that last item by the time it arrived on the floor. George Mason, of Virginia, spoke up. “Why is the provision restrained to Treason & bribery only?” he asked, according to James Madison’s notes. “Treason as defined in the Constitution will not reach many great and dangerous offences … Attempts to subvert the Constitution may not be Treason as above defined.” Mason moved to add “or maladministration.”

Madison, though, objected that “so vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate.” Gouverneur Morris further argued that “an election of every four years will prevent maladministration.” Mere incompetence or policy disputes were best dealt with by voters. But that still left Mason’s original concern, for the “many great and dangerous offences” not covered by treason or bribery. Instead of “maladministration,” he suggested, why not substitute “other high crimes & misdemeanors (agst. the State)”? The motion carried.

Constitutional lawyers have been arguing about what counts as a “high crime” or “misdemeanor” ever since. The phrase itself was borrowed from English common law, although there is no reason to suppose Mason and his colleagues were deeply familiar with its uses in that context. The Nixon impeachment spurred Charles L. Black, a Yale law professor, to write Impeachment: A Handbook, a slender volume that remains a defining work on the question.

Black makes two key points. First, he notes that as a matter of logic as well as context and precedent, not every violation of a criminal statute amounts to a “high crime” or “misdemeanor.” To apply his reasoning, some crimes—say, violating 40 U.S.C. §8103(b)(2) by willfully injuring a shrub on federal property in Washington, D.C.—cannot possibly be impeachable offenses. Conversely, a president may violate his oath of office without violating the letter of the law. A president could, for example, harness the enforcement powers of the federal government to systematically persecute his political opponents, or he could grossly neglect the duties of his office. That sort of conduct, in Black’s view, is impeachable even when it is not actually criminal.

His second point rests upon the principle of eiusdem generis—literally, “of the same kind.” As the last item in a list of three impeachable offenses, surely “high crimes and misdemeanors” shares some essential features with the first two. Black suggests that treason and bribery have in common three essential features: They are extremely serious, they stand to corrupt and subvert government and the political process, and they are self-evidently wrong to any person with a shred of honor. These, he argues, are features that a “high crime” or “misdemeanor” ought to share.

Black’s views on these points are not uncontested. Nixon’s attorneys argued that impeachment did require a crime. In 1974, before Black published his book, a report from the Justice Department split the difference, concluding that “there are persuasive grounds for arguing both the narrow view that a violation of criminal law is required and the broader view that certain non-criminal ‘political offenses’ may justify impeachment.”

John Doar, the attorney hired by the House Judiciary Committee to oversee the Nixon investigation, handed off the question of what constituted an impeachable offense to two young staffers: Bill Weld and Hillary Rodham. They determined that the answers they were seeking were to be found not in old case law, but in the public debates that raged around past impeachment efforts. The memo Weld and Rodham helped produce drew on that context and sided with Black: “High crimes and misdemeanors” need not be crimes. In the end, Weld came to believe that impeachment is a political process, aimed at determining whether a president has fallen short of the duties of his office. But that doesn’t mean it’s arbitrary. In fact, the Nixon impeachment left Weld with a renewed faith in the American system of government: “The wheels may grind slowly,” he later reflected, “but they grind pretty well.”

Some Democrats have already seen enough from the Trump administration to conclude that it has met the criteria for impeachment. In July 2017, Representative Brad Sherman of California put forward an impeachment resolution; it garnered a single co-sponsor. The next month, though, brought the white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and Trump’s defense of the “very fine people on both sides.” The billionaire activist Tom Steyer launched a petition drive calling for impeachment. A second resolution was introduced in the House that November, this time by Tennessee’s Steve Cohen, who found 17 co-sponsors. By December 2017, when Representative Al Green of Texas forced consideration of a third resolution, 58 Democrats voted in favor of continuing debate, including Jim Clyburn, the House’s third-ranking Democrat. On the first day of the new Congress in January, Sherman reintroduced his resolution.

These efforts are exercises in political messaging, not serious attempts to tackle the question of impeachment. They invert the process, offering lists of charges for the House to consider, rather than asking the House to consider what charges may be justified. The House should instead approve a resolution authorizing an impeachment inquiry and allocating the staff, funding, and other resources necessary to pursue it, as the resolution that initiated the proceedings against Richard Nixon did.