The U.S. Coast Guard is one of the five branches of the U.S. military—with the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps—but since 2003 it has been organizationally part of the Department of Homeland Security.

The DHS budget is one of several being frozen or sequestered by the current government shutdown, which is now in its fifth week and the longest in history. Members of the Coast Guard are among the hundreds of thousands of federal workers not receiving pay.

A reader who is part of a Coast Guard family writes:

These are the men and women who are actually engaged in providing security to our country. These folks are literally first responders who create a virtual wall that we take for granted. Whatever we might think about airport security theater, there is no doubt about the amazing work done by the Coast Guard.

Now I've got a kid about to graduate from the Coast Guard Academy, plus I have been following the extraordinary efforts by communities, restaurants, churches, banks, insurance companies... and the Coast Guard itself, in an effort to support so many enlisted folks who are in serious trouble right now. My kid and her friends are fine but what's happening with many enlisted folks is simply horrible.

With that intro in mind, here's what I think is the core issue at hand: this shutdown is a Chickenhawk Shutdown. Like the Chickenhawk Nation, most people have no clue.

Congresspeople get paid. Retirees get paid. Active duty military get paid. IRS refund checks get processed (by people who expect to eventually get paid), and lots and lots of other services continue to be provided.

I'm stealing this notion from a friend who argues the problem is we don't actually have a shutdown. It's a semi-shutdown … a faux shutdown. The vast majority of the American public has no clue except maybe they've heard there's drama in Wash DC., or maybe they were on vacation but couldn't get in to see the Grand Canyon.

Too many people still accept the general idea that government doesn't do anything so who cares if they shut it down? (Some considerable number want to shrink it until you can drown it in the tub.) So when people hear there's a shutdown, and 90% see no impact, it just cements that misconception.

The reader then quoted a new article by the recently retired commandant of the Coast Guard, Admiral Paul Zukunft, in Proceedings, the magazine of the U.S. Naval Institute.The article is pointedly called “Breaking Faith,” and in it Zunkuft says:

While the Department of Defense realized a new highwater mark in its 2019 appropriation, the Coast Guard was excluded from that package and has yet to see its appropriation for 2019 that began on 1 October.

To add insult to injury, the Coast Guard is no longer “doing more with less,” but “doing all with nothing.”

I have served shoulder to shoulder with our service members during previous government shutdowns and listened to the concerns of our all-volunteer force. This current government shutdown is doing long-term harm and is much more than pablum to feed the 24-hour news cycle.

We are now in uncharted waters given its duration and the hardship its causing, particularly at many Coast Guard installations that reside in high-cost communities along the U.S. coastline where service personnel already live paycheck-to-paycheck to pay the bills….

Mission-essential training is being deferred with egregious implications for a service that has as its motto: Semper Paratus—Always Ready….

The U.S. Coast Guard is a “service like no other” with the exception that Coast Guard men and women place service above self, exactly as do each member of the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps.

Those three poignant words—service before self—on a grand scale need to guide our political leaders to avert the calamity confronting the world’s best coast guard.

Video doesn’t mean irrefutable truth, though time and again it’s offered as proof, as explanation. This weekend, controversy boiled over around a viral video of Kentucky Catholic high school students in Washington for the March for Life, appearing to mock Native Americans who’d participated in the Indigenous Peoples March. Then a second video emerged, muddling the clarity of the first. The incident, Julie Irwin Zimmerman writes, ended up a Rorschach test. What’s a productive lesson to take from all this?

As vicious cold and snow enveloped the eastern U.S., a reminder that individual record cold days during any given year don’t erase decades of rising averages: The average time, for instance, between the last frost of spring and the first frost of fall has increased in every region of the U.S. since the early-20th century. A reminder, also, that both planetary warming and local emissions can dramatically alter a region’s weather patterns, and an entire region’s identity and way of life.

Uncertainty reigns in the story of the Moscow Trump Tower project. The special counsel spokesperson issued a rare statement, disputing parts of a BuzzFeed News report that the president himself allegedly directed his then-personal lawyer Michael Cohen to lie to Congress about the Moscow project. On Sunday, Rudy Giuliani, representing the President Donald Trump for free, appeared on TV to deny that Trump ever instructed Cohen to lie, while also saying discussions for the project may have stretched into November 2016, contradicting the president’s own statements (Giuliani later tried to walk back these comments).

Evening Read

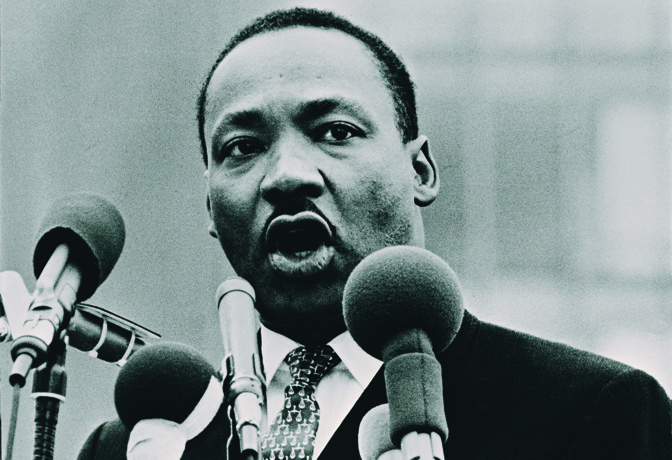

(Image: Santi Visalli / Getty)

In a May 10, 1967 address before the Hungry Club Forum in Atlanta, where sympathetic white politicians would meet out of the public eye with local black leaders, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of the gains made through the civil rights movement, but also of the “three major evils” imperiling such progress for black Americans. Racism was only the first of these evils.

→ Read King’s full speech here.

(Image: Clarence Williams / L.A. Times)

In the 90s, a white, Beverly Hills doctor named Sherman Hershfield had a stroke, began uncontrollably speaking in rhyme, started rapping at the Los Angeles hip-hop mecca Project Blowed, and in his 60s, became Dr. Rapp.

→ Read the full story here.

Have you tried your hand at our daily mini crossword (available on our website, here)? Monday is the perfect day to start—the puzzle gets bigger and more difficult throughout the week.

→ Challenge your friends, or try to beat your own solving time.

(Illustration: Araki Koman)

Dear TherapistEvery week, the psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb answers readers’ questions in the Dear Therapist column. Anna from Seattle writes:

For Christmas this year, my boyfriend surprised me with a ring. It’s sapphire and silver—beautiful. But it’s not an engagement ring. Without saying so outright, he made clear that it was just a ring. After dating for a few years, and living together for the past year and a half, I can’t help but be disappointed.

→ Read the rest, and Lori’s advice. You can write to Lori anytime at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

I am familiar with the ambiguities of video evidence—for example, through this piece I wrote from Israel more than 15 years ago, “Who Shot Mohammed al-Dura,” about the battle over the meaning of an inflammatory video there; or these two separate Twitter threads, first here then here, in the past few days from James Martin, a Jesuit priest and editor for America magazine, about the meanings of the multiple videos from the confrontation on the National Mall this past weekend.

I now believe that the “meaning” or “truth” of this recent encounter is likely to remain as contested as anything in the al-Dura case. The more additional evidence comes in, the more clearly it is taken to “prove” one interpretation of the case, or its opposite. “You must not have seen the full videos” is meant to be a conclusory statement, either way.

The more I have looked the evidence—the many, many videos, and the many statements, and the many timeline-analyses, and the many interpretations—the more I have recognized what I believe to be its reality, and the more I have understood that many others won’t see it the same way. Thus I regret weighing in on the case at all—or saying anything more than what I originally intended, which was admiration for a statement by the mayor of Covington, Kentucky, reaffirming his community’s belief in openness and inclusivity. Saying more was a mistake, which I would undo if I could.

The heart of this mistake was forgetting the difference between what I think or believe or conclude, on the one hand, and what will be provable to others. Here is a set of points about that frontier, which I’m numbering so I can refer back and forth to them:

1) The young man who was most prominently displayed in the video from the confrontation has released a statement about his intentions, saying that they were entirely peaceable and respectful. All he meant to do by standing in front of tribal elder with a drum, Nathan Phillips, for several minutes was to prevent further confrontations.

You can read the statement here.

The statement describes many background aspects of the event, from this student’s perspective. As a factual point, it doesn’t mention that a large number of the young men present, including the one issuing the statement, had chosen to wear MAGA hats.

2) As a complementary analysis of what the overlapping videos of the event show, this extensive Twitter thread by Lisa Sharon Harper matches what I believe the videos show. Similarly with this long thread from TBQ. As with the al-Dura case, there are long, detailed chronologies “proving” completely opposite interpretations of events. My point is that the two chronicles I’m mentioning seemed consistent with what I thought the videos showed.

3) The mail that has come in has been voluminous, and in three distinct categories.

Much is outraged, personally abusive, and profane. I won’t give examples.

Some is impassioned and angry, but inclines toward offering a denunciation of the “rush to judgment” by media members, including me, in this case. I’ll give samples of them below.

The rest is in the vein of this following message, usually from Americans and others who mention that they are non-white. This one comes from a well-known American academic, of the Baby Boomer era. He writes:

Nathan Phillips deserves both respect and emulation. He stepped in to prevent violence. [According to Phillips’s interviews, he was trying to avoid conflict between the students and a taunting group known as the Black Hebrews.] And he kept his cool in difficult circumstances.

Nathan Phillips had seen that smug smirk before, he knew what it stood for, and he acted with courage, dignity and self-control.

We have all seen that smug smirk. It is often a prelude to worse.

I saw the smirk while weighing in for a high school wrestling match. It was followed by trash talk with racial invective. I saw the smirk while sitting in a McDonalds in Indiana. It was followed by a slow-walk staredown with filthy racist remarks. I saw the smirk in a diner in Tennessee. It was followed by a man emptying a salt shaker on my eggs, flipping the food in my face, and following me as I headed toward the parking lot. I saw the smirk on the face of a drunk off duty police officer in a bar in my home town. It was followed by chest bumping and a threat to beat me if I did not go back where I came from.In these instances, nothing too bad happened because others acted.

A referee told the wrestler to cut the crap and imposed constraints on violence in the match. The girlfriend of the young man in the McDonalds told him he was behaving like a jerk. A brave cashier slowed up the guy in the diner by insisting that he pay for his breakfast, giving me time to reach my car. A seasoned bartender tried to calm the drunk officer, then asked him to come back another night.Unfortunately, the teachers, parents, and students on the Mall did not intervene.

I hope that the MAGA wearing tomahawk-chopping smirking young men of Covington will think of what they want to stand for.

More realistically, this incident will make bad behavior slightly less likely in the future.

People contemplating bad behavior in an era of mobile phones with cameras and social media will have second thoughts.

And essays on the incident will prime third parties in similar situations to speak out.

I have known this person for a long time, have seen him in his full professional respect and success, and had never before heard from him about these experiences of growing up as an Asian American in a small town on the East Coast.

4) Similarly, on what this reader, from Canada, recognized in Nathan Phillips:

Start with bunch of students on the mall wearing the emblem of a president who… has openly mocked the memory of the atrocity committed against the Lakota at Wounded Knee. Then when an Indigenous elder, protesting that breach of faith, and the racism behind it, attempts to walk to the Lincoln Memorial, these young men stand in his way. They don't move.

It seems their excuse is that they didn't know enough to defer to an elder with a drum. I would invite them, and anyone who defends them, to consider a different situation.

Imagine a group of young secularists going into a church. They walk around, they comment on the funny wood seats and the kitschy glass art, and then the organ starts playing and the priest and crucifer and taperers come in and they just stand in the aisle. Smirking, if deer caught in the headlights could smirk. And they don't move. They just stand there, disrupting the service.

Would those who defend these young men’s behaviour toward an Indigenous elder even remotely consider not knowing what to do an excuse in a church? Leave aside that ordinary decent politeness dictates moving aside for people who want to come through, particularly in a public place.

If you go into a church, it behooves you to know enough to sit down or leave when the service begins. If you live on this continent, surely it is not too much to ask that by high school you have enough of an understanding of the Indigenous culture that you give space to an elder singing a drum song. If not knowing better excuses these young men, it merely places a double indictment on their teachers and parents for not teaching them anything about indigenous cultures.

5) In a similar vein, from a reader who says that she, too, saw something she recognized on the Mall:

As a woman, the thought of as many as 150 high school boys, wearing not their school colors, but dressed in in-your-face MAGA regalia, loaded onto buses to interject themselves into a debate, that I believe, should be between a woman and her doctor, fills me with terror.

The decision to have an abortion is not one women take lightly. In fact, it is often the most difficult one a woman will ever make. The teen-party excursions Covington Catholic organizes to oppose reproductive rights, trivializes the agony many women experience when making that choice.

There is enormous injustice everywhere in this world, and many causes Covington Catholic could take up that would teach their young men humility and the value of public service. That they have chosen this issue, one that will never affect them personally, speaks to an arrogance that will only perpetuate the suffering of others. It does not surprise me that these young men were so clueless about the feelings of those around them that looked different than them. It is what they have been taught

6) And, from a reader in Texas who is politically conservative:

Can you think of anything dumber than taking a bunch of Catholic parochial high-school boys to a political protest in Washington, DC?…

“Black Israelites,” an activist Indian pow-wow, and feminist-abortioniks on parade…WTF were the priests and parents thinking?

7) Now, from the “you have made a serious mistake” category. The next message had an extended forensic analysis of who-did-what-when, which I have abbreviated because it is covered in the threads mentioned in #2. This reader writes:

I'm a longtime Atlantic subscriber and read your recent blog posts on what supposedly transpired Friday evening at the Lincoln Memorial, when a group of high schoolers were apparently waiting for buses after the March for Life.

I was not there, but I think you've done those boys a great disservice by jumping into the media scrum condemning them. I urge you to watch the 2 hr. video shot by a member of the Black Hebrews sect for context:

https://youtu.be/UQyBHTTqb38. [JF note: yes, I have seen all of these. ]

What it shows is that much of the Covington group—minors, by the way—were subjected to at least an hour of racist, anti-Catholic, anti-gay taunts and rhetoric from the Black Hebrews contingent, including f-bombs and repeated racial insults directed at them, before Mr. Phillips and his friends ever showed up….

Who knows, since there was no dialogue beforehand, but it is clear that Phillips and co. initiated the encounter, as they headed straight for the boys and waded into the middle of group, cameras aloft the entire time. There is no apparent fear or concern on their part, and the boys did not approach and surround them. Phillips just wades into their space, drumming and chanting loudly in an unknown tongue.

It's hard to know what the boys made of this scene. Most seem to be ignoring it. Did some think it a reaction to their football chants? Or an aggressive act after the barrage of abuse from the Black Hebrews, some of whom appear to be following Phillips closely into the mass of boys, cameras rolling the whole time?

This is not what's been portrayed. These are kids, encountering professional agitators for an hour, who then appear to be joined by Phillips, who extends the confrontation by approaching the young group directly and invading their space, not vice versa. Did Phillips know what the Black Hebrews had been up to for the prior hour? Who knows, but it is obvious that Phillips is mischaracterizing the events, and few media outlets are truthfully describing the Black Hebrews' rhetoric.

The kids are restrained throughout. There's nothing hinting at violence, threats, epithets, anti-immigrant statements, or even cursing from them. Some act like silly HS boys because they're kids, apparently led by adults who don't plan trips well. All have been hanging around outdoors in the cold waiting, idle, for over an hour.

The school and chaperones deserve some criticism, however. They should have told the kids to leave the MAGA gear home; it was a March for Life, not a Trump rally. They should have coordinated bus pickups better. They should have had more chaperones apparently. And they should have moved the kids away from the Black Hebrews taunters and aggressors within minutes.

8) Similarly:

By now, we have all learned that the initial media reporting of the incident on the Lincoln Memorial has been covered inaccurately, and the rush to judge these high school kids (mostly because of their skin color, gender, and choice in hat attire) has carried the narrative into dark corners of our public discourse.

It is disheartening to see so many people in our media rush to condemn fellow Americans based on misleading cell phone video snippets. Is the obsession with our post-Charlottesville sensitivity that chronic that we are OK with resorting to social-media justice devoid of context and all of the facts?

This incident provides a real opportunity for someone like yourself, whose initial response on the Atlantic’s website remains posted as of this email, to engage in the broader discussion of the conversation we really need to have right now.

Why is our culture OK with victimhood? Why is the media OK with deceiving viewers for the sake of being the first to report a story? Why is the media incapable of showing gratitude when proven wrong, and even more incredulous when an apology is warranted? The continued failure of writers and figures in the media to do this gives more ammunition to the voices who now view you and your ilk as illegitimate. As much as the media wants to bring down Trump (after creating him), the more people in the media flaunt their arrogance and refusal to be held accountable, the more average Americans buy into the “fake news” mantra. This story, along with the BuzzFeed story, proves it….

This incident involving these boys from Covington Catholic proves that our media culture is rancid with deception. Perhaps now is the time for someone like yourself to address it head on. After all, I can think of no better platform than the Atlantic. If I had given up entirely on her journalistic integrity, I wouldn’t be writing this.

***

9) I think about my own days as a high school student. I was 14 years old when Barry Goldwater got the GOP nomination for president, and—like most people in my home town, which gave him a majority—I was hoping for his (imagined) victory over LBJ. I even went to a nighttime Goldwater rally at Dodger Stadium, 60 miles away in Los Angeles, with a friend who was old enough to drive. There the organizers passed out T-shirts and bumper stickers that that said AU H2O—the chemical symbols for Gold Water, of course.

Southern California was brimming with racial tension in those days—it was less than a year before the Watts riots of 1965 in Los Angeles. The racial axis of the Goldwater-Johnson election was no mystery to anyone. Barry Goldwater got the GOP nomination just weeks after LBJ and his Democrats had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The only states Goldwater ended up carrying, apart from his home state of Arizona, were five from the old Confederacy: South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. (This was the beginning of the switch from the old “Solid South” Democratic majority in such states, to the modern “Southern Strategy” voting pattern of the South as the GOP’s base.)

I was capable of a lot of activities, with my friends, that fill me with remorse in retrospect. Among the least of them is that we cheered, as teenagers, at the Goldwater rally the way some teenagers cheer at Trump rallies today.

If we’d encountered an older black or Latino protestor in the Dodger Stadium parking lot after the rally, while we were wearing our AU H2O T-shirts (knowing what those would symbolize to non-whites, at the time), would I have stood with a group of friends directly in the older man’s face and stared him down? I don’t think so, but there is no way to know. These tests come unannounced. We might have been capable of it—in those times, with those passions, with that cocksureness of young men in a group. Still I think someone would have broken it off and walked away.

My wife and I escorted or chaperoned many sports-travel or other school-group events with our sons, when they were teenagers. Would the parents and teachers we saw at these events have let this kind of confrontation go on, without stepping in or moving the kids somewhere else? Again, I don’t think so, but I can’t know.

10) On the ongoing challenge of distinguishing what we expect from what we perceive:

I'll preface this by saying in most ways, I'm as progressive as they come. I mean, I'm from [a big city] that went over 90 percent for Clinton—and I moved to Europe in part because I can't stand to live in Trump's America. (And yes, I'm woke enough to recognize a huge amount of privilege in that set of circumstances.)

But the longer version of the video I saw shows a different story, and I think that the "story" someone comes away with depends heavily on their notions going into it in the first place.

In the longer version of the video, the kids are in a big group, mostly sitting around talking, playing grabass, typical teen boy stuff while waiting for a bus. There's a group of black folks maybe 10 or 20 yards away, with signs and protesting and yelling something; in the video, there's enough commotion and indistinct background noise that much of what people are actually saying is unclear.

And there's Mr. Phillips, with his drum. He moves between the two groups, then walks slowly over more in the direction of the boys. Many of them get up, and then they start yelling stuff- again, indistinct. Some start clapping and many start jumping in time with the drum. The commotion intensifies. I personally think I hear someone yelling about a wall, but can't tell.

Now, the bigger point here is that depending on our paradigm going in, we're going to see different things in the video. Some people say that he moved "aggressively" towards the boys—that's plainly not true. But it's also not true that they "surrounded" him, as though he were just standing around and they moved to him; he plainly moves himself between the two original groups and then closer to them.

Perhaps the most telling part (for me) about seeing what we expect to see was this: The mother of one of the boys was reported to have contacted a media reporter and she claimed that the true instigators were the "Black Muslims" who were harassing the boys.

While I have no doubt that the black folks were yelling stuff, it's been more recently reported that they are a group known as the Black Hebrew Israelites. And in the video, they're plainly not getting in the boys' faces; they're standing around hollering stuff, but there's no aggression.

And the fact that a group calling itself "Israelites" is confused for Muslims strikes me as pretty telling. She saw what she expected to see.

So... what does anyone see in the video? A smirking face that typifies white privilege and white supremacy, or a kid who was there to peacefully protest and just held his ground? A noble veteran Native trying to promote peace, or a guy who instigated something trying to get a rise out of someone?

I'd prefer to remain anonymous... which alone tells us something, that I feel like I can't be identified, because I don't want to put up with having to defend my "weak centrist" position.

11) As this last note #10 suggests, the response to this episode strongly reminds me of the controversy over Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation for the Supreme Court. What people saw in that case, and who they believed, depended very heavily on what they had grown used to seeing over the years. Everyone recognized a pattern, but the patterns completely differed.

After Christine Blasey Ford and others accused Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct when he was a Georgetown Prep student about the age of the students in the National Mall video, the cleavage in reactions followed lines of intellectual and emotional imagination. Whose suffering and unfair treatment could each of us more easily envision: The person who said she had been attacked? Or the person accused of the attacking?

In the Kavanaugh case, of course this meant whether each person more fully empathized with Christine Blasey Ford, for the damage she said she had endured—or instead the suffering and (possibly) unfair reputational damage inflicted on the accused, Brett Kavanaugh. In the current case: Is it easier to imagine and identify with the disrespect inflicted on Nathan Phillips? Or with the social-media pillorying of the high-school boys?

12) I know what I, personally, believe to be the reality of that encounter on the Mall, and how it fits into patterns of American history. But I should have realized how contested and ambiguous it would be. In those circumstances, I should have quoted the statement from the Mayor of Covington and not said more. I regret doing otherwise, am sorry for the consequences, and will do my best to learn from and not repeat this mistake.

13) On Martin Luther King’s birthday I offer a closing quote not from him but from C.S. Lewis, in Mere Christianity. (I have encountered this in a citation from Andrew Sullivan, in his blogging days, quoting Hilzoy in hers.) Lewis wrote:

Suppose one reads a story of filthy atrocities in the paper. Then suppose that something turns up suggesting that the story might not be quite true, or not quite so bad as it was made out. Is one’s first feeling, ‘Thank God, even they aren’t quite so bad as that,’ or is it a feeling of disappointment, and even a determination to cling to the first story for the sheer pleasure of thinking your enemies are as bad as possible?

If it is the second then it is, I am afraid, the first step in a process which, if followed to the end, will make us into devils. You see, one is beginning to wish that black was a little blacker. If we give that wish its head, later on we shall wish to see grey as black, and then to see white itself as black. Finally we shall insist on seeing everything — God and our friends and ourselves included — as bad, and not be able to stop doing it: we shall be fixed for ever in a universe of pure hatred.

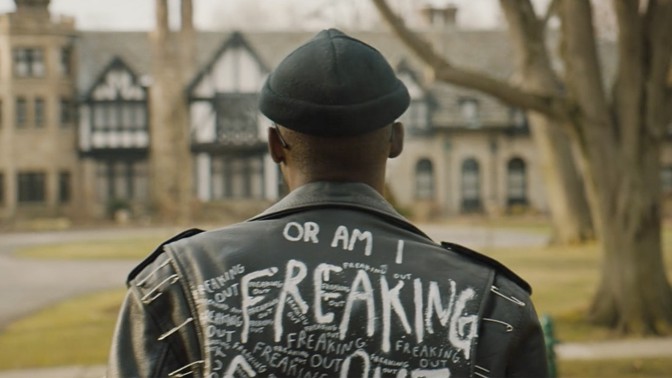

In a short, viral video shared widely since Friday, Catholic high-school students visiting Washington, D.C., from Kentucky for the March for Life appeared to confront, and mock, American Indians who had participated in the Indigenous Peoples March, taking place the same day.

By Saturday, the video had been condensed into a single image: One of the students, wearing a “Make American Great Again” hat, smiles before an Omaha tribal elder, a confrontation viewers took as an act of aggression by a group of white youths against an indigenous community—and by extension, people of color more broadly. Online, reaction was swift and certain, with legislators, news outlets, and ordinary people denouncing the students and their actions as brazenly racist.

But as the weekend wore on, a new video cast doubt on the clarity the original had appeared to offer. This one was shot by members of a Black Hebrew Israelite protest group that had also gathered at the Lincoln Memorial, where the incident took place. Over the hour-and-45-minute run time, members of the group mock and deride passersby of all stripes. According to a statement issued by Nick Sandmann, the Covington Catholic High School junior seen apparently intimidating the tribal elder in the original video, the students were also victims of harassment by the broader protest, and they had tried to defuse the situation by singing over the Black Hebrew Israelites. According to the statement, the encounter between Sandmann and Nathan Phillips, the Omaha elder, was a misunderstood moment taken out of context. Phillips, meanwhile, maintained that he and his companions felt threatened by the confrontation with the students, most of whom were white.

[Read: Video doesn’t capture truth]

Film and photography purport to capture events as they really took place in the world, so it’s always tempting to take them at their word. But when multiple videos present multiple possible truths, which one is to be believed? Given the new footage, some, such as the libertarian outlet Reason, said the students were “wildly mischaracterized.” Others, such as The Washington Post, tried to cast the matter more neutrally, concluding that the aftermath “seemed to capture the worst of America at a moment of extreme political polarization.”

But rather than drawing conclusions about who was vicious or righteous—or lamenting the political miasma that makes the question unanswerable—it might be better to stop and look at how film footage constructs rather than reflects the truths of a debate like this one. Despite the widespread creation and dissemination of video online, people still seem to believe that cameras depict the world as it really is; the truth comes from finding the right material from the right camera. That idea is mistaken, and it’s bringing forth just as much animosity as the polarization that is thought to produce the conflicts cameras record.

There’s an old dispute in film theory between form and content. For most people, the meaning of moving images seems to relate to the footage inside them—the people, settings, and events that the camera pointed at and captured. But in fact, the way those elements were selected, edited, and re-presented has an enormous impact on the way they are received and understood. In the case of the Lincoln Memorial encounter, neither the original video nor the new one explains what “really happened.” Instead, both offer raw material that can take on various meanings in different contexts.

Because the newer video of the Lincoln Memorial encounter is so much longer, some would contend that it offers clarity about how the conflict arose. But if you watch the video in its entirety, it’s hard to find much clarification. Instead, it offers a large quantity of raw material from the same time and place. That footage betrays just how easy it is to find provocative moments in an otherwise ordinary sequence of events.

For example: At one point, the Black Hebrew Israelite protester holding the camera engages with a woman who had pointed out that Guatemala and Panama are indigenous names with their own meaning, different from names such as Indian or Puerto Rico ascribed by Spanish conquistadors. “I am from Panama,” the cameraman claims, “so now I’m indigenous from Panama … We indigenous, so we out here fighting for you.”

As best I can tell, the speaker means to argue that allegedly being from Panama, a place host to some indigenous peoples that bears an indigenous name, aligns his interests with those of North American indigenous peoples who had assembled for the Indigenous Peoples March. To say that this is a spurious argument would be putting it mildly; it’s a bit like me, a white man who lives in Atlanta, home of the civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., arguing that my intentions are necessarily aligned with those of modern extensions of the black civil-rights movement, such as Black Lives Matter.

[Read: After the police brutality video goes viral]

That moment, which lasts less than a minute, could easily be extracted and shared on its own. It would make fine #content: Look at this protester trying to roll over his interlocutor with faulty reasoning! Look how she is lured in to making earnest arguments that bounce right off bad-faith interlocutors! There are dozens, hundreds of these latent, potential viral videos in the footage, all potential flash points for online controversy if selected and framed appropriately.

The Black Hebrew Israelites’ performance offers dozens of opportunities for similar brow furrowing, ranging from bemusing to derogatory. “A bunch of incest babies,” one of the Black Hebrew Israelites shouts at the amassing Catholic students at one point. When a passing black man attempts to defy the group, one of them responds, “You got all these dirty-ass crackers behind you, with a red ‘Make America Great’ hat on, and your coon ass wanna fight your brother.”

Via broadcast or on YouTube, it’s easy to organize those clips such that they indict the group of Black Hebrew Israelites and mar its intentions. That’s the same appeal that Sandmann made in his statement. He says that the African American protesters were saying “hateful things,” which inspired the group to sing school-spirit chants in an effort to drown them out. During this time, according to Sandmann, Phillips, the Omaha elder, waded into the crowd playing a drum. Sandmann and Phillips locked eyes—the most notable moment in the original, viral video. According to Sandmann, he only intended to defuse the situation, in part because he knew it was being recorded. But according to Phillips, the encounter was hostile—“hate unbridled,” he called it—and caused him and his companions to fear for their safety.

As the video and coverage of it proliferated, critics attempting to explain it searched for the truth in its content. “Viral Video Shows Boys in ‘Make America Great Again’ Hats Surrounding Native Elder,” The New York Times reported Saturday. On Twitter, people raced to condemn the students, the school, and the Catholic Church. But a day later, when the longer footage emerged, those initial conclusions seemed less certain. “A fuller and more complicated picture emerged,” the Times reported on Sunday. But even then, the content was still seen as the place to search for the truth. The Times eventually landed on the same milquetoast conclusion that The Washington Post did, concluding “that an explosive convergence of race, religion and ideological beliefs—against a national backdrop of political tension—set the stage for the viral moment.”

Those parries will likely continue back and forth, with individuals, legislators, and media outlets each offering their own take on the original video and all the information that has seeped out from it since. But fewer will acknowledge the role of video itself in manufacturing real and actual effects, no matter how the surrounding circumstances motivated or contextualized them.

For Sandmann and his colleagues, their actual intentions and motivations seem vital to any account of what took place. But not only can we never really know what those were, they also don’t matter once the original video has been shot and shared. That short clip shows a young man with a smirk, wearing a “Make America Great Again” hat, appearing to stare down a Native elder: Simply describing the scene, at this political and cultural moment, suggests a racist threat.

That’s not just because the internet makes it easy to come to simple and quick conclusions, and to spread those answers as truth before verification. It’s also because such an edit almost seems purpose-built to service that conclusion. It juxtaposes an almost perfect avatar for apparent white nationalism, MAGA hat and all, with the apparent cultural frailty of a brown-skinned victim carrying out an act of indigenous humility. Whether Sandmann and Phillips are telling the truth or not matters only marginally—the image and the clip take on a life of their own, reproducing a conflict that viewers have already been primed to seek out by the overall political situation and their place in it.

To understand just how susceptible images like this are to total reinterpretation, consider an alternative scenario. Imagine that instead of standing silently and seemingly smug, the teen had maintained a neutral countenance and then removed his MAGA hat from his head. Such an act would have been interpreted, almost universally, as a gesture of meekness and respect. Some would have overinterpreted it, no doubt, taking it as a sign that the student had shed not just the cap, a symbol of Trumpism, but all the ideologies bound up in that symbolic garment. And this interpretation would have cohered and spread no matter whether Sandmann really meant any of it or not. (I pointed out a similar feature in the Jim Acosta White House video, in which a small shift in the position of a camera could utterly change the apparent meaning of the resulting images.) The entire tenor of the viral moment would have flipped, and the students likely would have enjoyed being portrayed as meek heroes representing the tolerant promise of American youth.

Consider a change in framing or editing instead: Had the original clip been shot from the reverse angle, showing Sandmann and his classmates from the back, his MAGA hat visible but not his smirk, the meaning of the situation would have also changed. No longer does the student represent the worst stereotype of white intolerance, but now he becomes a mere prop for Phillips, whose drumming reads as both pacifist in its delivery and reception. My point is not to apologize for the students’ behavior, or even to explain it, but to underscore how a slightly different video might have convinced the very same viewers who censured the Covington Catholic students to reach exactly the opposite conclusion.

[Read: The great illusion of “The Apprentice”]

About a century ago, the Soviet formalist filmmaker Lev Kuleshov conducted a series of experiments with filmic montage. In the most famous one, he edited a short film consisting of short clips of various subjects: an actor’s expressionless face, a bowl of soup, a woman on a couch, a girl in a coffin. The same clips edited into different sequences produced different interpretive results in the viewer. The deadpan face of the actor appeared to take on different emotions depending on which image preceded or followed it—he appeared dolorous, for example, when seeming to “look at” the dead girl in the coffin. This effect of filmic editing has been called the Kuleshov effect, and it’s had an enormous influence on filmmakers including Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and Francis Ford Coppola. It also forms the backbone of reality television, in which meaning is almost entirely produced in the editing room.

From Sandmann’s statement to the Times’ walk-back, follow-up to the incident has focused on the larger circumstances, which are assumed to provide clarity. Sandmann claimed to offer a “factual account of what happened.” The Times admitted that the video excerpt had “obscured the larger context.” But there’s a problem: Understanding the larger context doesn’t really produce a factual account of what happened, as depicted in the original video.

Kuleshov’s disciple Sergei Eisenstein would eventually call editing, and montage in particular, the key formal property of cinema (the famous Odessa-steps sequence in his 1925 film Battleship Potemkin is the canonical example). These traits allow film to link together seemingly unrelated images, relying on the viewer’s brain to make connections that aren’t present in the source material, let alone the cinematic composition.

The power of editing comes from condensation, from film’s ability to compress events that unfold over a long period of time into one that takes place over mere moments. Today’s online video still relies on editing, of course, but even clips that appear uncut still participate in a version of the Soviet formalist project. Now the cameras inside the smartphones everyone carries produce a swarm of videos, many of which spread on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and other venues. The result is a seemingly infinite set of possible perspectives, real or faked, truthful or manipulative, all clamoring to present their edited rendition of events in front of the eyes and minds that would gestalt meaning from them. Now the process of selection is collective—all those thousands and millions of video cameras in everyone’s pockets scrabbling for the first or best attention.

Watching the almost two-hour video of the Black Hebrew Israelites only drives the point home—there are piquant moments of conflict, but mostly expanses of empty time, marked by moments of incoherence or inaudible exchanges. If this counts as broader context, it certainly doesn’t explain the events of the Covington student and the Omaha elder. Instead, it just provides the raw material out of which that moment was forged.

It’s tempting to think that the short video at the Lincoln Memorial shows the truth, and then that the longer video revises or corrects that truth. But the truth on film is more complicated: Video can capture narratives that people take as truths, offering evidence that feels incontrovertible. But the fact that those visceral certainties can so easily be called into question offers a good reason to trust video less, rather than more. Good answers just don’t come this fast and this easily.

Every year, on the third Monday in January, people play their hand at the same game. “What would Martin Luther King Jr. think?” becomes an unwritten essay prompt for op-eds, a topic of speeches and sermons, a call to action, and a societal rebuke. In this annual pageant, there are few who would ever mark themselves as living in opposition to the legacy of King, even as they work to dismantle it.

It was only natural that Vice President Mike Pence would quote King in defense of President Donald Trump’s decision to continue the ongoing government shutdown until he receives full funding for a border wall. “One of my favorite quotes from Dr. King was: ‘Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy’,” Pence said on CBS’s Face the Nation on Sunday, citing King’s famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech. “You think of how he changed America. He inspired us to change through the legislative process, to become a more perfect union. That’s exactly what President Trump is calling on Congress to do: Come to the table in the spirit of good faith.”

Pence, of course, is doing only what the current version of the holiday demands. Across the ideological spectrum, politicians must seek to fit themselves under the aegis of the Kingian legacy. That means a contingent of Americans who surely oppose the positions King held in his life are compelled to contort him into something friendly. Columns must wield King to attack everything from “identity politics” to the very act of “politicizing” King’s life itself. Democratic presidential hopefuls must employ King in order to make the case that each of their disparate platforms is the natural heir to his legacy. The sound bites evoking King are stretched like skin over the bones of existing debate. The figure celebrated looks nothing like the leader who lived—and who was killed—but like a granite-chiseled modern founding father, a collection of axioms by which our age is defined.

But beyond those axioms, there are core truths to who King was, what he believed, and what he endorsed. He was not an unknowable sphinx who spoke only in maxims. The first truth is that King was a person who began his career as a very young man, and who changed, learned, and grew over the course of a challenging and often controversial career. He was once a boy known in his family as “ML,” a raconteur who fancied himself a ladies’ man. He was only 26 when he was recruited to lead the Montgomery bus boycott, and while still in his 20s he ran an advice column for Ebony magazine. The gulf between that man and the weary 39-year-old who in his 1968 “Drum Major Instinct” speech lamented that “we’ve committed more war crimes almost than any nation in the world” is an immense one.

The second truth about King springs naturally from the first: What he believed over the course of his life changed, and was affected by the course of the civil-rights movement and by his own development and experiences as a leader. Kingian nonviolence, the philosophy and strategy that is most widely associated with him, changed over the course of his life from a tactical activism to an all-encompassing worldview that brought him to decry poverty in India, housing discrimination in Chicago, and the Vietnam War. King’s crucible in the spotlight at the forefront of the movement even led him to directly challenge and critique former versions of himself, and those who sought to preserve him in amber. In 1967, for example, he defended his prescription of civil disobedience while also allowing that “there is probably no way, even eliminating violence, for Negroes to obtain their rights without upsetting the equanimity of white folks.”

That second truth makes some of the annual celebration of King an exercise in absurdity. Most modern memorials take stock of King around the “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963—likely his popular zenith in the eyes of white onlookers—and few bother to look beyond that speech or the contents of a few passages. Even fewer peer into his early or late years. They miss the fraught political landscape of his death, the “white backlash” that he warned about, and the ways in which his legacy was whitewashed from the very beginning as a way to blunt his more pointed economic and societal critiques.

The third point follows. There were several policies that King not only advocated for, but that he found were necessary to reverse the evils of white supremacy. He outlined these policies specifically, and often in full detail. He sought race-specific measures such as affirmative action, outlined support for universal jobs and housing guarantees in his “Freedom Budget,” and in speeches announced his support for universal health care. And while he did not necessarily advance a comprehensive view on immigration, he evinced a clear support for global citizenship and for America’s mandate to shoulder the burden of global antipoverty programs. In a 1964 speech in East Berlin, King made that position clear: “For here on either side of the wall are God’s children, and no man-made barrier can obliterate that fact. Whether it be East or West, men and women search for meaning, hope for fulfillment, yearn for faith in something beyond themselves, and cry desperately for love and community to support them in this pilgrim journey.”

The way the country memorializes King today, it might be seen as a matter of partisan bias or controversy to point out that Pence, the White House, and supporters of the Trump administration stand firmly against the policies that King wanted. But this is not really a matter of opinion. The administration has eschewed any attempts at universal health care, sought to end affirmative action as it is implemented, and has looked to walk back existing measures to ensure affordable housing; the president’s history as a public figure is tied to alleged violations of the Fair Housing Act for which King advocated; and Trump has referred to developing nations as “shithole countries.” Not only does the administration’s policy agenda come completely into conflict with King’s, it is rooted firmly in a conservative movement that built itself in opposition to King.

That Pence and other standard-bearers within this movement can regularly lean on King’s legacy is a consequence of how the civil-rights leader has been canonized. When President Ronald Reagan signed the holiday into law, in 1983—reversing his own objections to the holiday, and earlier ones to King himself—he signaled that America had accepted King in its pantheon of similarly revered leaders, people such as George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. But in order to do so, King’s legacy had to be repackaged in a way similar to theirs. While in both of those cases, the truths about American slavery are conveniently stripped away, the popular history of King must erase these three truths about him. In that historical amnesia, the current political status quo operates, doomed to rediscover King only once a year.

Like many people who spend too much time on Twitter, I watched with indignation Saturday morning as stories began appearing about a confrontation near the Lincoln Memorial between students from Covington Catholic High School and American Indians from the Indigenous Peoples March. The story felt personal to me; I live a few miles from the high school, and my son attends a nearby all-boys Catholic high school. I texted him right away, ready with a lesson on what the students had done wrong.

“They were menacing a man much older than them,” I told him, “and chanting ‘Build the wall!’ And this smirking kid blocked his path and wouldn’t let him leave.” The short video, the subject of at least two-thirds of my Twitter feed on Saturday, made me cringe, and the smirking kid in particular got to me: His smugness, radiating from under that red MAGA hat, was everything I wanted my teenagers not to be.

“Where were they chanting about building the wall?” my son asked. His friends had begun weighing in, and their take was decidedly more sympathetic than mine. He wasn’t sure what to think, as he was hearing starkly different accounts from people he trusted. I doubled down, quoting from the profile of Nathan Phillips that The Washington Post had quickly published online, in which he said he’d been trying to defuse a tense situation. I was all-in on the outrage. How could the students parade around in those hats, harassing a man old enough to be their grandfather—a Vietnam veteran, no less?

By Sunday morning, more videos had surfaced, and I started looking for the clip that showed them chanting support for the wall. I couldn’t find it, but I did find a confrontation more complicated than I’d first believed. I saw a few people yelling terrible insults at the students before Phillips approached, which cast an ugly pall over the scene. I saw Phillips approach the students; I had believed him when he said he’d intended his drumming to defuse the tension, but I also wondered how a group of high-school students could have gleaned that when he didn’t articulate it in a language they might understand.

I hated the MAGA hats some of the kids were wearing, their listless tomahawk chops, the way some of their chanting mocked Phillips’s. But I also saw someone with Phillips yelling at a few of the kids that his people had been here first, that Europeans had stolen their land. While I wouldn’t disagree, the scene was at odds with the reports that Phillips and those with him were attempting to calm a tense situation.

As I watched the longer videos, I began to see the smirking kid in a different light. It seemed to me that a wave of emotions rolled over his face as Phillips approached him: confusion, fear, resolve. He finally, I thought, settled on an expression designed to mimic respect while signaling to his friends that he had this under control. Observing it, I wondered what different reaction I could have reasonably hoped a high-school junior to have in such an unfamiliar and bewildering situation. I came up empty.

Let’s assume the worst, and agree that the boy was being disrespectful. That still would not justify the death threats he’s been receiving. It would not justify the harassment of the other Covington Catholic student who wasn’t even in Washington, D.C., but who was falsely identified as the smirker by some social-media users. Online vigilantes unearthed his parents’ address and peppered his family with threats all weekend long, even as they were trying to celebrate a family wedding, accusing them of raising a racist and promising to harm their family business.

The story is a Rorschach test—tell me how you first reacted, and I can probably tell where you live, who you voted for in 2016, and your general take on a list of other issues—but it shouldn’t be. Take away the video and tell me why millions of people care so much about an obnoxious group of high-school students protesting legalized abortion and a small circle of American Indians protesting centuries of mistreatment who were briefly locked in a tense standoff. Take away Twitter and Facebook and explain why total strangers care so much about people they don’t know in a confrontation they didn’t witness. Why are we all so primed for outrage, and what if the thousands of words and countless hours spent on this had been directed toward something consequential?

If the Covington Catholic incident was a test, it’s one I failed—along with most others. Will we learn from it, or will we continue to roam social media, looking for the next outrage fix? Next time a story like this surfaces, I’ll try to sit it out until more facts have emerged. I’ll remind myself that the truth is sometimes unknowable, and I’ll stick to discussing the news with people I know in real life, instead of with strangers whom I’ve never met. I’ll get my news from legitimate journalists instead of from an online mob for whom Saturday-morning indignation is just another form of entertainment. And above all, I’ll try to take the advice I give my kids daily: Put the phone down and go do something productive.

Letters From the Archives is a series in which we highlight past Atlantic stories and reactions from readers at the time.

On April 12, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy led a march of some 50 black protestors through Birmingham, Alabama. It was Good Friday. “We want to march for freedom on the day Jesus hung on the cross for freedom,” King said prior to the event. But their march was cut short. King and Abernathy, among many others, were arrested by city police for parading without a permit; the leaders were placed in solitary confinement.

This particular march was just one of a handful of demonstrations in Alabama that spring organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Civil-rights fighters picketed, used white-only libraries, and participated in sit-ins at white-only lunch counters. In response to the freedom movement, a blanket injunction was issued by Circuit Judge W. A. Jenkins Jr. prohibiting “every imaginable form of demonstrations including boycotting, trespassing, parading, picketing, sit-ins, kneel-ins, wade-ins and the inciting or encouraging of such acts,” the Associated Press reported. The April 11, 1963, article noted that King—“the behind-the-scenes director of the current movement”—and other SCLC organizers, who were told specifically not to demonstrate, were planning to defy the injunction and march anyway. “This [is] a flagrant denial of our constitutional privileges,” King declared.

While in jail, King was given a copy of “A Call for Unity,” an open letter written by eight moderate, white Alabama clergymen criticizing the demonstrations initiated by “outsiders” and urging negotiations instead. “We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized,” they wrote. “But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.” Using what he could find—the margins of the newspaper in which the statement was published, scraps of paper, his attorney’s legal pad—King wrote a letter in response to the religious leaders.

He not only clarified that the SCLC was invited by its local affiliate to Birmingham, but also explained that he could not “sit idly by” in his hometown of Atlanta as Birmingham fought for freedom. “Injustice anywhere,” he famously wrote, “is a threat to justice everywhere.” Certain promises had been made in negotiating sessions, such as the removal of “humiliating racial signs from stores,” King wrote; however, those promises had not been kept. There was no alternative but nonviolent direct action, which, King later noted, would never be “well-timed” according to the timetable of those who hadn’t experienced segregation: “For years now I have heard the word ‘wait.’ It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This ‘wait’ has almost always meant ‘never.’” King expressed how disappointed he was in the clergymen and, more broadly, the white church and its leadership. “In the midst of blatant injustices inflicted upon the Negro,” King wrote, “I see white churches stand on the sidelines and merely mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities … I hope the church as a whole will meet the challenge of this decisive hour.”

King’s letter, now widely known as “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” was published in a handful of newspapers and magazines, including The Atlantic, which printed it in August 1963 under the title “The Negro Is Your Brother.”

The letters from readers that The Atlantic printed in response were largely positive.

Having witnessed sit-in demonstrations in Knoxville, Tennessee, open-occupancy hearings in the San Francisco Bay Area, and a civil-rights demonstration in his hometown, Richard E. Gillespie of Phoenix, Arizona, agreed with King’s statement that “the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is … the white moderate, who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” Gillespie said King’s words had “indelibly imprinted themselves in my mind as a classic articulation of the motivation of the white moderate.”

A few readers put King’s ideas in conversation with other pieces from the August issue.

“Dr. King’s emphasis of the fact that the churches have not taken a stand on this matter of integration,” wrote Margaret G. Taber of Madison, New Jersey, “is a very sad one.” Taber applied King’s critique of religious institutions to Agnes Meyer’s article “The Nation’s Worst Slum,” also in the August 1963 issue of The Atlantic, in which she outlined how Washington, D.C., had neglected to give non-elite blacks work opportunities. Meyer’s point that “the black elite have not helped those of their poorer brethren,” Taber wrote, was “well taken.” But urging black communities to “raise [their] own standards” would not, Taber argued, “solve the problem.” She found her way back to King:

Few of our churches have preached that a person should be accepted as an individual regardless of color or race. Yet they should take the lead in urging acceptance of Negroes or Puerto Ricans or other minority groups.

In addition to “The Nation’s Worst Slum,” the August issue included a series called “Our Gamble in Space” about the potential moon landing. The juxtaposition “aroused an ironic reaction” in Frances Records Storms of Glasgow, Missouri, who took issue with the idea of “world prestige” that Franklin A. Lindsay emphasized would come with winning the space race in his article “The Costs and the Choices.”

“When the propaganda and rationalizations turn to national prestige, what can counteract Little Rock, New Orleans, Birmingham, Ole Miss, Medgar Evers?” Storms asked. He considered the moon landing the wrong priority: “How convincing is the argument of international one-upmanship or the iffyness of landing instruments or men on Mars in the context of human needs at home?” While the estimated $30 billion for the moon project “would not answer all of the questions raised by Agnes Meyer, by Dr. King,” Storms wrote, that money “plus a proportionate surge of human effort would go a very long way toward redressing the inequities existing for citizens of all colors in the United States.”

Finally, David K. Donald of Garden City, Michigan, thanked The Atlantic—“with all my heart as a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant”—for printing the letter “for a larger impact.”

When President Donald Trump announced in a tweet that he was withdrawing U.S. troops from Syria, his abrupt decision kicked up one of the most thoroughly bipartisan maelstroms of condemnation in his first two years as president. Trump had telegraphed his intention for months, if not years, but the sudden declaration on December 19 went against the advice, and public pronouncements, of his own national-security team. Republican allies in Congress protested loudly. The widely respected defense secretary, retired Marine Corps General James Mattis, resigned in protest the next day. Within two days, another top U.S. national-security official followed Mattis out the door. On Sunday, in a television interview and in a newspaper op-ed, he laid out his dissent—and his fears for the future.

Brett McGurk coordinated the U.S.-led coalition of more than 60 nations that fought the Islamic State terror group and gave international legitimacy to American involvement in a war-torn country where Iran and Russia were making headway. He was one of the rare Barack Obama appointees to keep his job in the Trump administration, but he came with an impeccable Republican pedigree.

Soon after finishing a clerkship for U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, a conservative icon, McGurk went to Iraq and worked as a lawyer for the Coalition Provisional Authority. He joined President George W. Bush’s national-security team and stayed on after President Obama’s election, winning enough confidence that the Democrat nominated him as ambassador to Iraq in 2012. He withdrew his nomination after a leaked racy email drew attention to his affair in Baghdad with a reporter, whom he had married by the time of his nomination.

In 2015, President Obama named McGurk the presidential envoy to the global coalition against the Islamic State, and he stayed in that role under Trump. The veteran diplomat had planned to leave his post in mid-February, according to the Associated Press, but he expected U.S. direct engagement to continue for at least several more months. “Nobody is declaring a mission accomplished,” he told reporters at a State Department briefing on December 11. “It would be reckless if we were just to say, ‘Well, the physical caliphate is defeated, so we can just leave now.’”

Barely a week later came Trump’s withdrawal announcement, quickly followed by McGurk’s resignation, effective December 31. He joined a group of foreign-policy experts at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, one of his new colleagues, called him “the consummate professional diplomat,” which sounded like an endorsement of his resignation and a subtle rebuke of Trump’s abrupt announcement.

Trump took to Twitter to attack McGurk, pointing out that the diplomat was an Obama appointee and bashing him as a “grandstander” since he had simply moved up his exit by six weeks. The president added that he did not know McGurk, his own point man in the fight against the Islamic State.

[Read: The U.S. isn’t really leaving Syria and Afghanistan]

Now McGurk is taking his case to the American public. He says that even with a slightly elongated withdrawal timetable, Trump’s decision has damaged U.S. strategic interests and national security.

“Only Russia and Iran hailed Trump’s decision,” McGurk wrote in a Washington Post op-ed that appeared in Sunday’s print edition. “Whatever leverage we may have had with these two adversaries in Syria diminished once Trump said we would leave.” The diplomat wrote that America’s strategic rivals now face little constraint on their military buildup in Syria. Israel, the United States’ closest ally in the region, must step up air strikes to fend off Iranian threats along its northeastern border.

Safety is more assured, though, for Bashar al-Assad because “without us, any chance of upending this mass-murdering dictator, propped up by Iran and Russia, is a pipe dream,” McGurk wrote. U.S. partners are reopening embassies in Damascus and moving closer to Assad, hoping to “dilute Russian, Iranian and Turkish influence in Syria.”

The expected power vacuum may come back to haunt the United States, much as it did after the withdrawal from Iraq, McGurk forecasted. “The Islamic State and other extremist groups will fill the void opened by our departure, regenerating their capacity to threaten our friends in Europe—as they did throughout 2016—and ultimately our own homeland,” he wrote. While defeating the terror group was Trump’s professed goal, the former diplomat said, “his recent choices, unfortunately, are already giving the Islamic State—and other American adversaries—new life.”

McGurk also went on CBS’s Face the Nation on Sunday for one of his first, if not his first, television appearances since leaving the government, aside from a recorded Atlantic event earlier this month. He argued that Trump’s disruption of the status quo was unnecessary.

[Watch: Atlantic Exchange featuring Brett McGurk, Graeme Wood, and Jeffrey Goldberg]

“In this campaign in Syria since 2015, we’ve had two Americans killed in action,” he said. “We built this campaign plan to answer for those who believe that we should not be overinvested in these conflicts. Americans are not fighting; we built a force of 60,000 Syrians to do the fighting. American taxpayers are not spending money on civilian stabilization or reconstruction costs; the coalition is doing that. So it was a sustainable campaign plan.” (A note on Syrian reconstruction funding: The State Department had $230 million budgeted for that purpose, but the Trump administration canceled the spending in August, according to CNN. McGurk helped secure a commitment of $300 million from allies, with one-third of the money coming from Saudi Arabia.)

McGurk also defended himself against Trump’s charge that his resignation was political, pointing out that he worked under Bush, Obama, and Trump. “I’ve served all three administrations,” he said. “I’ve worked on policies that I fully supported. You work on policies here in the government that you might not support. You argue your case. In this case, I think the entire national-security team had one view, and the president in a conversation with [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan just completely reversed the policy.”

If the president can’t be persuaded to reverse his reversal, McGurk added, then the departing U.S. troops should not be given new goals to accomplish while they withdraw. “We cannot add additional missions onto our force while they are trying to withdraw under pressure,” he said, “because withdrawing under pressure from a combat zone is one of the most difficult military maneuvers we can ask our people to do.”

McGurk added that a Turkish military push into Syria would result in a humanitarian disaster for America’s Kurdish allies, who have borne the brunt of the campaign against the Islamic State. But in his op-ed, he dismissed Trump’s latest tweeted proposal, a 20-mile safe zone, as an impractical last-minute idea. He fears what is to come.

“Believe me, there’s no plan for what’s coming next,” he said on CBS. “Right now, we do not have a plan.”

Rudy Giuliani, the former New York City mayor who’s representing President Donald Trump for free, is keeping up his public-relations war on Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation. In a pair of appearances on Sunday-morning talk shows, he stuck to the playbook: Attack Mueller’s credibility, and insist that all of Trump’s statements and actions were legal. Giuliani admits a fair amount but always insists that no crime was committed.

The president’s attorney once again said that discussions about a Trump Tower Moscow project may have continued as late as November 2016, contrary to the president’s previous statements that he had nothing to do with Russia, where he had long sought to do business. On NBC’s Meet the Press on Sunday, Giuliani said talks may have gone on “as far as October, November” 2016. That matches his statement last month that Trump’s written answers to Mueller’s questions “covered up to November 2016.”

[Read: Rudy Giuliani for the defense]

This is the timeline that first landed Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal lawyer, in legal trouble. Cohen originally testified to Congress that talks had ended by January 2016, before the GOP primary, and he has since said in court filings that he lied to stay consistent with Trump’s “political messaging.”

That false testimony was the subject of BuzzFeed News’ contested report last week that alleged Trump had directed Cohen to lie. The story went unconfirmed by other journalists and, in a rare rebuke, was challenged by the special counsel’s spokesman, who said, “BuzzFeed’s description of specific statements to the special counsel’s office, and characterization of documents and testimony obtained by this office, regarding Michael Cohen’s congressional testimony are not accurate.” (In a story Sunday on Giuliani’s comments, the news outlet said it continues to stand by its reporting.)

After Giuliani said BuzzFeed should be “sued” and “under investigation”—though any government probe would likely violate the First Amendment—he addressed the details of the story and conceded that Trump may have talked with Cohen about his testimony, though not to plan a lie.

“As far as I know, President Trump did not have discussions with [Cohen about his testimony], certainly had no discussions with him in which he told him or counseled him to lie,” Giuliani said on CNN’s State of the Union. “If he had any discussions with him, they’d be about the version of the events that Michael Cohen gave them, which they all believed was true.”

“And so what if he talked to him about it?” Giuliani added, seeming to argue that Trump could not have told Cohen to lie, because the president didn’t independently remember the details of Russian negotiations but instead depended on Cohen for the timeline. “Michael Cohen was the guy in charge of this,” Giuliani said. “President Trump was running for president. So … you go to Michael Cohen, you say, ‘Michael, what happened?’”

Cohen is expected to testify again before both houses of Congress, beginning February 7 with an appearance before the House Oversight Committee. Representative Adam Schiff, the California Democrat who this month took charge of the House Intelligence Committee, said on CBS’s Face the Nation that he’s “given Michael Cohen a date that we’d like him to come in, either voluntarily or, if necessary, by subpoena.” Senator Mark Warner, the Virginia Democrat who’s the vice chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said on NBC that he and Chairman Richard Burr, a North Carolina Republican, got Cohen to agree to a public hearing.

Warner also dismissed Giuliani as a spokesman for a client whose account keeps changing. “I almost feel bad for him,” the senator said. “He keeps having to readjust his stories as more facts come out.”

[Read: House Democrats shift their focus from collusion to leverage]

Democrats have charged that Trump misled Americans about his pursuit of business in Russia, but Giuliani quibbled over semantics to deflect that criticism.

In July 2016, then-candidate Trump tweeted that he had “ZERO interests in Russia” and said he had nothing to do with the country. In an October debate with Hillary Clinton, he said, “I don’t deal there. I have no businesses there. I have no loans from Russia.” About a week before his January 2017 inauguration, he tweeted in capital letters that “I HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH RUSSIA—NO DEALS, NO LOANS, NO NOTHING!”

Cohen’s continued discussions with Russians about a Trump Tower Moscow, and the letter of intent Trump himself signed in October 2015, seemed to contradict those claims. However, Giuliani argued that there was nothing incongruent about Trump’s statements, since the “project … never went anywhere,” he said on NBC. “There was one letter of intent that was nonbinding. That’s the whole thing. So I don’t know if you’d call it a project even.”

The defense lawyer characterized the Trump Tower Moscow letter as an “active proposal” that did not constitute a deal or a business. He compared it to the proposals under consideration by his security consultancy, which continues to develop lucrative contracts abroad while Giuliani represents the president for free, drawing ethics criticism, since foreign governments may see him as a conduit to the Oval Office.

“It’s like my business,” Giuliani said. “I make proposals to do security work, probably got six of them out right now. If you were to ask me what countries am I doing business in, I’d just tell you the two I’m doing business in. Not the other six, because I may never do business there.”

[Read: Why didn’t Trump build anything in Russia?]

In addition to defending Trump legally and politically, the former federal prosecutor also continued to sow doubt about the special counsel’s ethics. He claimed that Mueller’s team is pressing witnesses to lie about Trump and Russia. Jerome Corsi, a conservative conspiracy theorist, claims that the prosecutors are offering him leniency if he pleads guilty to lying about his conversations concerning WikiLeaks and hacked emails with the Trump confidant Roger Stone during the campaign.

“I have the documents. It was leaked to me,” Giuliani said on CNN. “They gave him a script. If he reads from the script, no jail. If he doesn’t read from the script, he gets maybe five years in jail.”

Giuliani decried Mueller’s treatment of Paul Manafort, the former Trump-campaign chairman who was convicted of tax fraud last year before he pleaded guilty to conspiracy and witness tampering. In November, the special counsel’s office said Manafort broke his plea agreement by continuing to lie to investigators. While awaiting sentencing, he’s been jailed alone due to his high profile, but Giuliani sees a strong-arm tactic by Mueller: “He’s got the man in solitary confinement now for six months, and he keeps questioning him and trying to pressure him to say things that are not true.”

Giuliani also defended Trump’s cryptic call last week for law enforcement to investigate Cohen’s father-in-law, which critics see as threatening to use government resources to intimidate a witness. Giuliani claimed that Cohen was lying to protect his father-in-law from prosecution, which justified an attack.

“That is a defense to a criminal accusation,” Giuliani said on CNN. “And if we can’t do that, we’re not in America.”

On the subject of whether the Mueller probe should be overseen by William Barr, Trump’s nominee for attorney general, Representative Schiff said the answer is no. The House Intelligence Committee chairman said senators should vote against Barr’s confirmation because of two statements he made about the probe during last week’s hearings.

First, Schiff said, Barr “would not commit to following the advice of ethics lawyers if they urged him to recuse himself” from overseeing the investigation. Jeff Sessions had taken ethics officials’ advice and recused himself, outraging Trump. Barr did say that Sessions was right to recuse himself, breaking with Trump, but he also said it was an “abdication of his own responsibility” to commit in advance to following the recommendation of ethics officials. “I will seek the advice of the career ethics personnel,” Barr said Tuesday, “but under the regulations, I make the decision as the head of the agency as to my own recusal.”

[Read: Bill Barr breaks with Trump on the Mueller probe]

Schiff also objected to Barr’s position on releasing Mueller’s final report. The nominee said in his opening statement that “it is very important that the public and Congress be informed of the results of the special counsel’s work. For that reason, my goal will be to provide as much transparency as I can consistent with the law.” However, under questioning from Democratic senators, he would not commit to publishing the report or even sending it to Congress. “I don’t know, at the end of the day, what will be releasable,” he said at the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, pointing to possible issues with executive privilege. The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake noted that while the committee’s top Democrat, Senator Dianne Feinstein, seemed to find his position reasonable, others in her party might not. Schiff falls into that camp.

“Either one of those ought to be reasons not to confirm him,” Schiff said, “but the combination of both should be completely disqualifying.”