Quando chovia forte no centro do Rio de Janeiro dos séculos 18 e 19 era comum que corpos mortos e apodrecidos de pessoas escravizadas boiassem na enchente. Quando não era o corpo inteiro, muitas vezes os passantes cruzavam com pernas e braços dilacerados, vagando pelas esquinas. Insetos, bactérias, cães, gatos e urubus aproveitavam-se. A repugnância diante dos corpos destroçados ficou bem registrada em centenas de documentos da Câmara de Vereadores e nos relatos de viajantes. Em 1814, o alemão G. W. Freireyss escreveu: “Havia um monte de terra da qual, aqui e acolá, saíam restos de cadáveres descobertos pela chuva que tinha carregado a terra e ainda havia muitos cadáveres no chão que não tinham sido ainda enterrados”.

Freireyss estava de certa maneira enganado. Os cadáveres a que se referia não seriam “ainda enterrados”. Pelo contrário, eles já tinham sido enterrados, com quase nenhuma terra sobre seus corpos, e agora era a chuva que ia desenterrando esses homens e mulheres. Freireyss, na realidade, descrevia a indignidade de um Cemitério de Pretos Novos, espaços dedicados ao enterro (ou ao descarte) dos corpos de escravizados africanos recém chegados ao centro do Rio de Janeiro.

Em vez de dar visibilidade a sua história, a prefeitura preferiu esconder o cemitério dos cariocas.É sobre um desses cemitérios, o que funcionou em frente à Igreja de Santa Rita, que a terceira linha do Veículo Leve Sobre Trilhos, o VLT carioca, acaba de ser construída. Em vez de dar visibilidade a sua história, a prefeitura preferiu esconder o cemitério dos cariocas.

No início dos anos 1700, a corrida pela exploração do ouro na região de Minas Gerais fez disparar o número de desembarques no Rio de Janeiro. Eram dezenas de milhares de crianças, mulheres e homens que, a cada ano – sequestrados desde a Costa da Mina, na Guiné, do Senegal, de Angola e de muitos outras partes da África – desembarcavam na Praia do Peixe, centro do Rio que, naquele começo de século, ia se transformando na mais brutal cidade escravagista que o mundo já conheceu. Se houvesse compradores, os escravos eram comercializados ali mesmo, onde hoje é a rua Primeiro de Março, na região da Assembleia Legislativa do estado. Às vezes, agentes de inspeção de saúde entravam nos barcos para fiscalizar e impedir o desembarque de algum escravo muito doente. Outros, também muito doentes, eram vendidos a preços baixíssimos para comerciantes pobres, que assim faziam uma aposta: se houvesse melhora, o preço subia na revenda. Quem não era negociado, mas resistira à viagem com saúde, era levado aos mercados.

A frequente morte de quem descia sem saúde dos navios negreiros virou problema público importante no Rio por volta de 1710. A falta de dignidade dos enterros estava angustiando o clero do Rio. Foram os religiosos que exigiram que o rei Dom João V enviasse dinheiro para construir um cemitério especialmente dedicado a esses africanos. A primeira ideia é que ele fosse construído aos pés do Morro do Castelo, onde hoje está a Biblioteca Nacional, na região da Cinelândia. Mas o local decidido foi outro, muito mais próximo ao ponto de desembarque: em frente à Igreja de Santa Rita, na Freguesia de Santa Rita, na atual rua Marechal Floriano, também no centro do Rio.

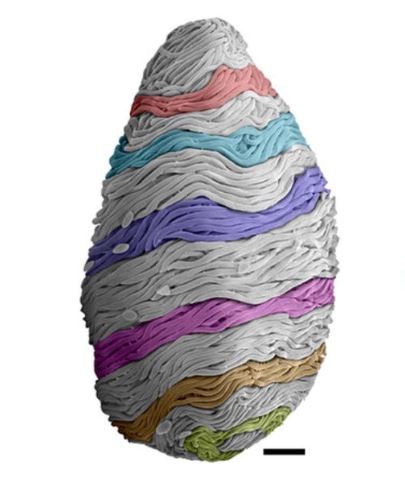

No século XIX, o Cemitério de Pretos Novos de Santa Rita já estava soterrado pela falta de memória. Na imagem, negros e negras buscam água no chafariz que havia na região.

Pintura de Eduardo Hildebrant - Largo de Santa Rita (1844)

Foi lá, aproximadamente entre os anos de 1722 e 1774, que funcionou o primeiro cemitério de Pretos Novos do Rio. Os enterros não eram gratuitos. Quem operava e cobrava pelo serviço era a igreja de Santa Rita. “A entidade católica cobrava do Estado pelo serviço. Apesar disso, além de serem os enterros feitos em cova rasa, os corpos eram enterrados nus, envoltos e amarrados em esteiras, sem qualquer ritual religioso, reza, encomendação ou sacramento”, escreveu o historiador Murilo de Carvalho na introdução do livro “À flor da Terra” do também historiador Júlio César Medeiros.

Se sequer havia ritual religioso para os escravizados que já eram católicos, convertidos ainda na África, é bem razoável pensar que menos respeito ainda recebiam aqueles escravizados devotos de religiões africanas ou mesmo do islã. A pergunta que fica é: quantos seres humanos foram descartados ali em Santa Rita, sem roupa, respeito religioso ou dignidade?

Começaram longos meses de debates sobre como o presente respeita o passado. Ou como o passado grita para ser ouvido pelo presente.Essa conta é bastante difícil, mas pode seguir a pista de um único documento sobrevivente, hoje no Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Nele, o historiador João Carlos Nara encontrou a Procuradoria da Câmara de Vereadores tentando convencer o Tribunal a levar o Cemitério dos Pretos Novos de Santa Rita, uma região então bastante movimentada, para um local mais afastado, conhecido como Valongo – o que de fato aconteceu. Ao descrever as atividades, a Procuradoria apontou que houvera 220 enterramentos apenas no primeiro semestre de 1766. Se a média deste ano se mantivesse, ao multiplicar as mortes pelos 52 anos de cemitério, chegaríamos a total de mais de 20 mil pessoas “enterradas” por ali.

<u>Era sobre esta história de escravidão e morte, em Santa Rita, que a prefeitura projetou passar a terceira e última linha do bilionário projeto do VLT<u/>, que custou, ao todo, R$ 1,1 bilhão aos cofres públicos. As obras da linha 3, que liga o aeroporto Santos Dumont à Central do Brasil, começaram em abril de 2018, sem qualquer conversa com a sociedade civil ou movimentos negros. Mas, ao saber dos trabalhos, não demorou para grupos de negros organizados reclamarem alto. Eles identificam ali ancestrais de suas histórias. Muitos arqueólogos também ligaram as sirenes, fizeram barulho, exigindo uma proteção atenta do Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional, o Iphan, órgão diretamente responsável por preservar sítios arqueológicos.

O VLT foi obrigado a contratar uma empresa de arqueologia para realizar escavações. Foi formada então uma comissão, chamada de Pequena África, nome de uma área do centro do Rio, para acompanhar a execução das obras e, principalmente, para exigir que houvesse respeito à memória do povo negro do Rio de Janeiro. O primeiro pedido do movimento foi de que as obras da linha 3 fossem paralisadas, especialmente no trecho da igreja. O VLT atendeu, e começaram ali longos meses de debates sobre como o presente respeita o passado. Ou como o passado grita para ser ouvido pelo presente.

Obras demoraram 8 meses e reviraram o asfalto de toda a extensão da rua Marechal Floriano Peixoto.

Foto: Caetano Manenti

O VLT tinha pressa. O dinheiro do Ministério das Cidades e da Prefeitura (na Parceria Público Privada com o VLT) estava disponível, numa época de vacas magérrimas para obras urbanas no Brasil e no Rio. Para piorar, o início dos trabalhos, marcado para janeiro, atrasara em quatro meses.

‘Era a chance que se tinha de, finalmente, conhecer o passado do cemitério.’Enquanto Iphan, VLT e movimento negro discutiam, a prefeitura do bispo Marcelo Crivella lavava as mãos. Os representantes do Instituto Rio Patrimônio da Humanidade fizeram questão de dizer que a polêmica não era deles, mas do Iphan. O prefeito Crivella estava muito mais preocupado com o Memorial do Holocausto. Em junho, chegou a fazer um show beneficente e, cantor gospel que é, se apresentou de graça para ajudar na arrecadação.

No primeiro momento das conversas, havia pouco consenso. Mercedes Guimarães, presidente do Instituto dos Pretos Novos, entidade criada para gerir a memória daquele que foi o segundo cemitério de Pretos Novos do Rio, na região da Praça da Harmonia, não queria que os trens passassem por cima dos mortos de Santa Rita: “Eu acho não tinha que ter VLT aí. Tinha que ter era monumento, dizendo o que foi ali. Aquilo é um bloco testemunho. Ali tinha que se falar o que foi o cemitério, qual a intenção daquele cemitério, contar o período que ele funcionou”.

Empresa contratada de arqueologia realizou escavações em outros trechos, mas não no local onde havia o Cemitério de Pretos Novos de Santa Rita.

Foto: Tatiana Nukowitz/Divulgação Iphan

Muitos historiadores e arqueólogos, claro, queriam escavações, principalmente para proteger os ossos que sempre estão em risco em grandes obras de infraestrutura como essa. Era a chance que se tinha de, finalmente, conhecer o passado do cemitério, como defende Nara: “Se não temos muita documentação, é a arqueologia que deve suprir essa deficiência. Muita gente tem medo de que os remanescentes sejam tratados como fósseis. Artefatos arqueológicos serão aquilo que nós dissermos que eles são. Se nós dissermos que é um fóssil, ele será tratado cientificamente como tal. Se dissermos que é uma ossada, isso terá uma perspectiva forense. Se nós dissermos que são remanescentes humanos, isso implica que existe uma solidariedade, existe uma preocupação e uma afeição por aquilo”.

No meio de toda essa discussão, a prefeitura dava suas caneladas ou, no conceito do líder da oposição, o vereador Tarcísio Motta, do PSOL, suas “Crivelladas”. Em nota divulgada nos grandes jornais que se debruçavam sobre o assunto em agosto, a Companhia de Desenvolvimento Urbano da Região do Porto, que representa a administração de Crivella no imbróglio, minimizava a certeza de que ali sim havia funcionado um grande cemitério de Pretos Novos. O documento dizia que “o trecho passará por pesquisa arqueológica como determina a legislação para melhor compreender o sítio arqueológico que se supõe que exista no Largo de Santa Rita, hoje ainda no campo da especulação”.

‘O trecho passará por pesquisa arqueológica como determina a legislação para melhor compreender o sítio arqueológico que se supõe que exista no Largo de Santa Rita, hoje ainda no campo da especulação.’Este repórter estranhou tanto a declaração que fez questão de questionar a representante da prefeitura presente em reunião promovida pelo Ministério Público no fim de agosto. Afinal, a prefeitura desconhecia a existência do cemitério? A pergunta simplesmente não foi respondida. Eu voltaria a questionar o governo municipal em setembro, dessa vez em seminário no Arquivo Nacional, mas o representante de Crivella, Antônio Carlos Barbosa, presidente da CDURP, assinou a lista de presença logo na chegada do evento e foi embora.

Fato é que a prefeitura não se dedicou em dar visibilidade à existência do cemitério. Nenhum release, nenhuma postagem, nenhum debate, nenhum pronunciamento, nada foi feito para chamar a atenção de que a cidade tinha, à frente dela, com a avenida aberta para obras, um Cemitério de Pretos Novos ali. Na única oportunidade de falar da cultura e história africana no período, em cerimônia no Museu de Arte do Rio de Janeiro, o bispo apresentou um rodízio de gafes para todos os gostos, provando que sabe tanto de história do Brasil como governar a cidade, ou seja, quase nada.

“Villegagnon condenava a morte os soldados que furnicassem com as índias, embora a natureza fosse muito forte para atraí-los. Foi expulso dessa cidade. E vieram para cá os portugueses que já eram uma raça mestiça. Foram com as índias que os portugueses nos deram nossos primeiros heróis: os bandeirantes”, disse Crivella.

“Nem o Ibérico, nem o índio poderiam suportar o esforço da indústria do açúcar. Ela necessitava de uma força muito maior. Então vieram para cá muitos africanos. E hoje nós não somos brancos, nós não somos negros, nós não somos amarelos, nós não somos vermelhos, somos brasileiros”.

Voltando ao debate do cemitério, Luiz Eduardo Negrogun, presidente do Conselho Estadual dos Direitos do Negro, estava revoltado com os nomes das estações que o VLT havia apresentado. A companhia insistia que as paradas tinham que ter referência geográfica e, assim, decidira que a última estação, próxima ao Palácio Duque de Caxias, quartel-general do Comando Militar no Leste, se chamaria Estação Duque de Caxias. Negrogun exaltou-se: “Não queremos esses nomes! Não vão ser esses nomes! Principalmente Duque de Caxias, racista, assassino, homofóbico!”.

Mas ainda havia a questão das obras e das escavações. O que fazer? Paralisar tudo? Desviar o traçado do VLT? Escavar para pesquisar? Para expor? Para ressepultar?

Negrogun disse que, mesmo dentro do movimento negro, havia muitas opiniões: “Tinha quem queria tirar os ossos. Outros que tivesse as escavações mas que deixassem janelas com os ossos à vista. Tinha uma outra discussão para impedir a obra. Mas nós não somos contra o progresso. Queríamos um diálogo para que houvesse uma reparação, um reconhecimento mínimo”.

O cemitério que a Prefeitura não deu nenhuma atenção virou, ao menos, nome de uma estação.Negrogun trouxe enfim a opinião do Comitê: a comunidade negra não queria as escavações. “Se tem escavação, tem remoção dos artefatos encontrados. Aquilo não são artefatos, são ossos de nossos ancestrais. Não queríamos que fosse removido dali para serem levados para outro lugar, para ficar exposto, ou abandonado, encaixotado. Quando escava, você sabe como começa, mas não sabe como vai terminar”, diz. “É como se teus antepassados estivessem enterrados num sítio de vocês e aí passasse uma draga revirando todas aqueles ossos, aquilo ali seria uma profanação do leito eterno dos nossos parentes”.

O professor Nara não concorda com o termo profanação. “Salvamento arqueológico não é profanação. Salvamento é para salvar o que seria destruído”. Outra historiadora, a professora Mônica Lima, trazia, no entanto, um meio termo. Aceitava que pequenas mostras fossem coletadas para o estudo, mas preferia que o sítio arqueológico fosse preservado.“Eu fico pensando sempre nas pessoas e nas suas relações com a morte. Para os africanos, a relação com a morte tem uma importância enorme. Que direitos temos nós? Nós abriríamos as covas que se têm nas igrejas mais antigas do Rio para estudar aqueles corpos da sociedade branca?”

Enfim, quando o VLT mostrou disposição para alterar os nomes das estações, instalar tótens informativos sobre a história negra na região e ainda demarcar o espaço do cemitério com pedras portuguesas com desenhos de Rosas Negras, o Comitê da Pequena África, então, deu o ok para a continuação das obras. O Iphan também autorizou que os trilhos passassem sobre o cemitério. A prefeitura se deu por satisfeita e a obra, a partir de então, seguiu em ritmo acelerado até o fim de 2018.

Negrogun disse que a única sugestão que não foi acatada foi de alterar a última estação de Duque de Caxias para Almirante Negro João Cândido, um dos maiores heróis do movimento negro contemporâneo. No fim, nem um, nem outro: ficou estação Cristiano Ottoni (nome da Praça)/Pequena África. Uma outra agora se chama Camerino/Rosas Negras, enquanto a derradeira se chama Santa Rita/Pretos Novos. O cemitério que a Prefeitura não deu nenhuma atenção virou, ao menos, nome de uma estação.

De toda forma, Crivella, como era de se esperar, não foi poupado das críticas. A prefeitura tinha a responsabilidade de ter tratado a história negra com muito mais respeito e atenção. Assim como Pereira Passos, o bispo que virou prefeito, ao revirar o centro, não lembrou daqueles que construíram a cidade. A professora Mônica Lima considera que faltou uma compreensão do que o cemitério poderia significar. “As obras do centro do Rio não podem ser tratadas apenas como questão de mobilidade urbana, mas de uma relação com a história da cidade”. Mercedes Guimarães foi ainda mais dura: “Os pretos novos estavam esperando uma coisa melhor: um monumento, mas pessoas se meteram e, em vez de fazer uma coisa bacana, legal, infelizmente, aceitaram as migalhas do colonialismo”.

‘As obras do centro do Rio não podem ser tratadas apenas como questão de mobilidade urbana, mas de uma relação com a história da cidade.’Até mesmo o prefeito Marcelo Crivella não parece muito satisfeito com o VLT, herança de Eduardo Paes e das administrações mdbistas na cidade, no estado e no país. Disse ele, recentemente, ao Valor Econômico: “Você acha justo um VLT, que foi negociado no tempo deles, que o município deve bancar, todos os dias, se não houver 300 mil passageiros? Hoje tenho 70 mil passageiros. E tenho que pagar 230 mil passagens diariamente. Você acha um bom negócio isso? São R$ 293 mil por dia, R$ 9 milhões ao mês”.

A linha 3 do VLT, que deveria ser inaugurada antes do natal de 2018, ainda não começou a operar. Crivella agora bate o pé e afirma que a prefeitura quer alterar o contrato que, segundo ele, dá prejuízo para os cofres da cidade. Não há mais uma previsão para o início das viagens. A instalação dos tótens também não tem prazo definido, tampouco a construção do mosaico em pedras portuguesas que vão delimitar a área do cemitério.

A comunidade negra espera que seja rápido, mais rápido que os 240 anos que já se passaram desde que o último Preto Novo foi descartado por ali.

The post Está aqui, sob o VLT, o cemitério de escravos que a prefeitura do Rio dizia ser ‘especulação’ appeared first on The Intercept.

Paranoid conspiracy theories about George Soros — the liberal philanthropist and financier cast, in starkly anti-Semitic terms, as a shadowy puppet master bent on toppling governments — are now so common that it is easy to forget that this viral meme was first injected into the far-right imagination by Fox News more than a decade ago.

An otherwise valuable new article for BuzzFeed by the Swiss journalist Hannes Grassegger — which explains how Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán, focused his entire re-election campaign on the imaginary threat posed by Soros, a Hungarian-born Jew — is marred by an incomplete history of the meme. Grassegger, who is perhaps lucky not to have access to Fox broadcasts, incorrectly attributes the creation of the anti-Soros meme to the late Arthur Finkelstein, an American political consultant who advised Orbán.

Grassegger is right to report that Finkelstein and his partner George Birnbaum “turned Soros into a meme” in Hungary, starting in 2013, portraying the billionaire as an enemy of the Hungarian people in posters and attack ads disguised as public service announcements. But his claim that the two men “created a Frankenstein monster that found a new life on the internet,” ignores the earlier role that Fox News played in pushing the coded anti-Semitic attack on Soros.

Years before Finkelstein advised Orbán to use Soros as a punching bag — casting his financial support for education, human rights, and democracy in Hungary as somehow nefarious — the Fox News hosts Bill O’Reilly and Glenn Beck had already vilified the Holocaust survivor in similar terms. O’Reilly started by accusing Soros of secretly giving “millions to politicians who will do his bidding,” before Beck went full Stürmer by describing Soros as “the Puppet Master.”

O’Reilly first introduced Fox News viewers to his caricature of Soros as a shadowy financier bent on “imposing a radical left agenda” on Americans on April 23, 2007. The goal of Soros, O’Reilly warned darkly, was “to buy a presidential election.”

To do this, O’Reilly claimed, “Soros has set up a complicated political operation designed to buy influence among some liberal politicians and smear people with whom he disagrees.” O’Reilly’s complaint about Soros-backed smears was a reference to the billionaire’s support for Media Matters, a liberal watchdog group that had irked the Fox News pundit by regularly fact-checking and debunking his false claims.

O’Reilly’s analysis was then echoed by one of his guests, the conservative talk-radio host Monica Crowley, who claimed that Soros’s donations to liberal groups were “a brilliant way to get around the campaign finance laws in this country,” which he had been able to keep secret “before you just exposed him, because the mainstream media protects him.” Another guest, the far-right political activist Phil Kent, later chimed in to describe Soros as “really the Dr. Evil of the whole world of left-wing foundations” who “really hates this country.”

Although O’Reilly did not refer to Soros’s ethnicity, his criticism of the financier as a shadowy string-puller appealed to the imaginations of anti-Semites online. Less than a year later, Soros was portrayed as “a Jewish tycoon,” secretly directing American foreign policy from inside the White House, in a bizarre animated propaganda film broadcast on Iranian television.

The public service announcement produced by Iran’s intelligence ministry warned viewers that Soros was “the mastermind of ultra-modern colonialism,” who “uses his wealth and slogans like liberty, democracy, and human rights to bring the supporters of America to power.” In the cartoon, Soros was shown plotting to overthrow Iran’s government, with the help of the CIA, John McCain, and Gene Sharp, a political scientist whose theoretical work on nonviolent protest influenced color revolutions in Eastern Europe.

By October 2008, the idea that Soros was secretly controlling American politics was even lampooned on “Saturday Night Live,” in a sketch that identified the financier in an on-screen graphic as “Owner, Democratic Party.”

The actor playing Soros in the sketch, a mock C-SPAN broadcast, even joked that he had drained hundreds of billions of dollars from the American economy during the financial crisis and was planning to devalue the dollar.

Two years later, Fox’s Glenn Beck made the echo of anti-Jewish Nazi propaganda impossible to ignore, calling Soros a “puppet master” who “collapses regimes” in a broadcast — complete with actual puppets — that columnist Michelle Goldberg described as “a symphony of anti-Semitic dog-whistles.”

In his long indictment of Soros, what Beck did not say about the list of governments he claimed the philanthropist had helped to topple was striking. Before claiming the United States would be Soros’s next “target,” Beck ominously intoned, “Soros has helped fund the ‘Velvet Revolution’ in the Czech Republic, the ‘Orange Revolution’ in the Ukraine, the ‘Rose Revolution’ in Georgia. He also helped to engineer coups in Slovakia, Croatia, and Yugoslavia.” Beck failed to mention that in each of the countries he named, Soros had provided support to popular pro-democracy groups battling repressive regimes led by Communist or former Communist autocrats.

There were also no coups in Slovakia, Croatia, or Yugoslavia. Slovakia was created by the so-called velvet divorce, the peaceful dissolution of the federal state of Czechoslovakia by democratically elected leaders in 1993; Croatia’s wartime president, Franjo Tudjman, an authoritarian former Communist general, died in office in 1999 and was replaced by a former member of his party after a democratic election; Slobodan Milosevic, the Yugoslav leader who was most responsible for the brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing that killed tens of thousands in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo, resigned in 2000, following street protests after his loss in a democratic election.

Beck’s elaborate conspiracy theory, sketched out on both sides of a series of blackboards, was so unhinged that it inspired an extended parody by Jon Stewart.

Asked at the time what he made of Beck’s claims “that you are the mastermind who is trying to bring down the American government,” Soros told Fareed Zakaria of CNN: “I would be amused if people saw the joke in it, because what he is doing, he is projecting what Fox, what Rupert Murdoch is doing — because he has a media empire that is telling the people some falsehoods and leading the government in the wrong direction.”

“Fox News,” Soros added, “has imported the methods of George Orwell, you know, Newspeak, where you can tell the people falsehoods and deceive them.”

While it is difficult to trace the influence of Fox News in Europe, where it is not broadcast on television, copies of Beck’s program, “The Puppet Master,” have been widely shared online, and the conspiracy theory soon became a matter of faith for far-right commentators on American websites.

An online editorial cartoon, published in 2011, showed how well-established conspiracy theories about George Soros were by then.

The conspiracy theories about Soros are now so widespread that earlier this week, Yair Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister’s son, shared a link to a post by Pamela Geller, a far-right blogger, who distorted remarks made by Soros about how he survived the Holocaust to falsely accuse him of having been “a Nazi collaborator.”

Yair Netanyahu is retweeting Pamela Geller who is spreading antiSemitic lies https://t.co/DTjEqea9lG

— Mairav Zonszein ??? ??????? (@MairavZ) January 22, 2019

Even after parting company with both Beck and O’Reilly, Fox has continued to focus obsessively on spreading invective and false claims about Soros as a hidden mastermind of liberal causes.

In April, one of the network’s new stars, Tucker Carlson, declared on air that “George Soros hates the United States.” Another new arrival, Laura Ingraham, claimed that Soros was behind protests against the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, despite a credible allegation of sexual assault. And in October, Lou Dobbs of Fox Business News made no objection when Christopher Farrell, the head of the far-right Judicial Watch, claimed that Soros was funding a caravan of asylum-seekers marching to the U.S. border, through the “Soros-occupied State Department.”

Straight out of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Just moments ago, Lou Dobbs guest Chris Farrell (head of Judicial Watch) says Caravan is being funded/directed by the "Soros-occupied State Department". pic.twitter.com/QBSong7uk1

— Josh Marshall (@joshtpm) October 27, 2018

The same week, Fox News reported that a pipe bomb had been sent to the home of “Democratic mega-donor George Soros.”

“This comes at a time,” the Fox News correspondent Bryan Llenas observed from outside Soros’s home, “when Soros’s name has been recently evoked by right-wing activists, including with the caravan moving forward. Rep. Matt Gaetz, just a few days ago tweeted, suggesting that Soros perhaps was part of the funding — funding the migrant caravan moving to the border. And the president himself has evoked Soros’s name recently, in Missoula, Montana, talking about Soros perhaps funding liberal protesters.”

The post The Plot Against George Soros Didn’t Start in Hungary. It Started on Fox News. appeared first on The Intercept.

Defense attorneys for the accused mastermind of the USS Cole bombing asked a federal appeals court on Tuesday for a fresh start to his trial, alleging that a glaring instance of judicial misconduct tainted their client’s military tribunal.

Lawyers for Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri asked the District of Columbia Court of Appeals to take the extraordinary step of vacating decisions made under Air Force Col. Vance Spath, the military judge who was in charge of Nashiri’s case between 2014 and Spath’s retirement from the military last year.

They argued that Spath presided over the case with an undisclosed conflict of interest, noting that for years, he was angling for an appointment with the Justice Department while advancing Nashiri’s case on terms favorable to the prosecution team.

In November, the Miami Herald revealed that Spath had applied for a job with the Justice Department in 2015 to work as an immigration judge. At the same time, he was presiding over Nashiri’s case, in which Justice Department lawyers were part of the prosecution team seeking the death penalty.

Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions has been an outspoken supporter of Guantánamo’s military commissions. In 2017, he called the prison “a very fine place” to put new terror suspects, and he reportedly intervened last year to scuttle a plea deal that would spare 9/11 defendants the death penalty.

According to defense filings, in the years after he applied for an appointment with the Justice Department, Spath touted his “aggressive trial schedule,” while accusing Nashiri’s defense lawyers of creating “constant roadblocks, recalcitrance, and disobeyance of orders.”

Michel Paradis, a Defense Department counsel representing Nashiri, told the three-judge panel that Spath had “angled for an appointment from the Attorney General at the same time the Attorney General and Department of Justice had substantial interest in [Nashiri’s] case,” and that “he traded on the fact that he was the judge in this capital case for his own personal gain.”

Paradis also said that Spath had used one of his rulings favorable to the Justice Department in Nashiri’s case as a writing sample for his application. Spath ultimately got the job and was sworn in as an immigration judge in September.

Military judges are appointed to oversee cases by the Defense Department, and do not have the same lifetime tenure that federal judges enjoy.

Joseph F. Palmer, an attorney for the Justice Department, told the three-judge panel on Tuesday that it was normal for military judges to seek employment while trying a case. He also raised a procedural objection, saying that Nashiri’s attorneys should have allowed the military commission to rule on Spath’s recusal before bringing the case to federal court.

“Judges rule on decisions regarding their own recusal all the time,” Palmer said, “and it’s within the discretion of an appellate court to decide, ‘Let’s hear from the judge himself. Let’s have him explain why he did what he did.’”

Alka Pradhan, a human rights lawyer who represents a different Guantánamo detainee, told The Intercept that it wasn’t unusual for a military judge to seek employment elsewhere, but that didn’t excuse the conflict of interest.

“In this particular situation, where [the judge is] in a military commission presiding over a prosecution that is run entirely by the Department of Justice and has to pronounce on motions being brought by Department of Justice attorneys, that is a situation where it’s inappropriate for a military judge to be looking for employment with the Department of Justice,” Pradhan said.

Tuesday’s argument ruling is not the first time Spath has been in the national spotlight. In August 2017, Nashiri’s defense team found a surveillance microphone in the room they used to meet with Nashiri. In response, the lawyers sought to find out whether their privileged communications had been spied on. Spath denied the request, dismissing the claims as “fake news.”

“That in and of itself caused a legal conflict,” said Pradhan. “The client has no reason to trust them if the client can’t trust that their communications are privileged. The second level of conflict is that they were not allowed to tell Nashiri about the eavesdropping.”

Three of Nashiri’s lawyers resigned after consulting a legal ethics expert and getting permission from Guantánamo’s chief defense counsel, Brig. Gen. John Baker. In response, Spath held Baker in contempt of court and sentenced him to be confined to quarters for three weeks, a ruling later overturned by a federal court. Spath also told prosecutors to draft warrants for U.S. marshals to seize two of Nashiri’s lawyers and force them to appear before him, but instead shut down the trial, pending review by a higher court.

Nashiri is accused of planning the USS Cole bombing in 2000, when Al Qaeda operatives sailed a boat carrying explosives up to the U.S. Navy destroyer, which was refueling in the port of Aden, Yemen, and detonated the bombs, killing 17 U.S. sailors and injuring 39 more. But in the more than 16 years since, Nashiri’s case has repeatedly stopped and started, hamstrung by constant procedural hurdles. It has become a symbol of the inability of Guantánamo military commissions to prosecute alleged terrorists.

An artist rendering shows Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri during his military commissions arraignment at the Guantánamo Bay detention center in Guantánamo, Cuba, on Nov. 9, 2011.

Image: Janet Hamlin/AP

Nashiri was captured in the United Arab Emirates in 2002 and rendered to a secret CIA prison in Thailand. According to a report by the Senate Intelligence Committee, CIA interrogators tortured Nashiri even after they deemed him “cooperative and truthful,” shackling him in stress positions, waterboarding him, and on at least one occasion, force-feeding him rectally. Part of his interrogation was overseen by now-CIA Director Gina Haspel.

Legal commentators have held up Nashiri’s case as an example of how the military commissions system creates a web of procedural problems. Steve Vladeck, a professor of law at the University of Texas law school, wrote last year that Nashiri’s case was a “ten-layer dip” of procedural hurdles — from basic jurisdictional problems, to the fact that much of the evidence against him was obtained under torture, to ethics complaints against the presiding judge and requirements for qualified defense counsel in capital cases.

If the court grants Tuesday’s request, it could have ramifications beyond Nashiri’s trial.

Pradhan told The Intercept that a ruling in favor of Nashiri would give defense attorneys more power to challenge violations of attorney-client privilege, which have occurred in other cases before the military commissions.

“For the people who work on these cases, it would mean that we have more freedom to act in accordance with basic legal ethics than we thought we had,” said Pradhan, who represents 9/11 defendant Ammar al-Baluchi. “We’ve been operating under conflicts or potential conflicts for a very long time.”

The Miami Herald reported earlier this month that Spath’s successor overseeing Nashiri’s case, Air Force Col. Shelley Schools, recently accepted a new job as an immigration judge, a Justice Department position. Schools has not yet heard arguments in the Nashiri case, but her new position does not begin until summer, meaning that she could potentially preside over motions until then.

Paradis argued Tuesday that Schools’s upcoming retirement further underscores the need for a federal court to intervene.

“We’re going back before a judge that, at a minimum, will have a jaundiced view of our arguments here,” he said.

Prosecutors have said they would not oppose a defense request to reassign the case to a new judge. If that happens, whoever is chosen would be the fourth judge to oversee Nashiri’s case.

The post Guantánamo Prisoner Says Judge Used Pro-Government Rulings to Curry Favor With the Justice Department appeared first on The Intercept.

The Trump administration on Wednesday made a quiet move that opens the door for the religious right to use the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act to discriminate against able foster parents whose religious views are in conflict with those of an agency.

On the 33rd day of the government shutdown, Steven Wagner, principal deputy assistant secretary at the Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, signed a waiver giving special permission to a federally funded Protestant foster care agency in South Carolina to break federal and state law, using strict religious requirements to deny Jewish, Muslim, and Catholic parents from fostering children in its network.

After months of lobbying by Reid Lehman, president and CEO of Miracle Hill Ministries, South Carolina lawmakers, and Gov. Henry McMaster, Wagner signed a waiver that lets the agency keep its federal funding, despite warnings by the state Department of Social Services that it’s violating federal and state nondiscrimination law, as well as internal agency policy, by denying parents of the Jewish faith from fostering children. The agency also rejects parents who are agnostic and atheist — anyone who is not a Protestant Christian.

“We have approved South Carolina’s request to protect religious freedom and preserve high-quality foster care placement options for children,” Lynn Johnson, assistant secretary for HHS Administration for Children and Families, said in a statement. “By granting this request to South Carolina,” she continued, “HHS is putting foster care capacity needs ahead of burdensome regulations that are in conflict with the law.”

The signed waiver, stalled for months, could have larger ramifications for other states waging battles over religious freedom in the foster care system, legal experts say. The waiver argues that HHS nondiscrimination regulations are broader than those outlined in the specific Foster Care Program Statute, which specifies that agencies receiving federal funding can’t deny foster parents based on race, color, or national origin — but not religion.

“You state that South Carolina has more than 4,000 children in foster care, that South Carolina needs more child placing agencies, and that faith-based organizations ‘are essential’ to recruiting more families for child placement,” the waiver reads. “You specifically cite Miracle Hill, a faith-based organization that recruits 15% of the foster care families in the SC Foster Care Program, and you state that, without the participation of such faith-based organizations, South Carolina would have difficulty continuing to place all children in need of foster care.” The letter then goes on to make the case that if Miracle Hill isn’t provided an exception to federal rules, other “faith-based organizations operating under your grant would have to abandon their religious beliefs or forego licensure and funding,” in violation of RFRA.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton in December issued a similar request to the HHS Administration for Children and Families to either repeal the nondiscrimination rules governing federal child welfare funding or to exempt Texas and providers in the state from it. It’s unclear whether the current waiver will apply to the Texas request.

The Texas request clearly asks for permission to discriminate based on religious belief and sexual orientation. The letter to ACF argues that the federal rules governing funding for child welfare programs “does not authorize HHS to prohibit discrimination on characteristics other than race, color, or national origin, or to mandate particular treatment of same-sex marriages.”

“Congress knows how to include or exclude nondiscrimination policies in its welfare funding statues,” Paxton’s letter reads, “and its decision to focus on only race, color, and national origin in Title IV-E means no other forms of discrimination are prohibited by funding recipients.”

The Trump administration has prioritized religious freedom for those of a Christian faith, and conservative lawmakers have used that momentum to try to chip away at a body of federal nondiscrimination law that they argue unfairly burdens organizations that only want to serve people within their own religion.

Eighty Republican legislators in May signed a letter to President Donald Trump on behalf of faith-based Child Placing Agencies they say are being targeted because of their mission. The letter includes a specific recommendation to repeal the federal rule that protects people from discrimination in HHS-funded programs on the basis of religion, race, ability, gender identity, sexual orientation, or any other “non-merit” characteristic. The letter condemns the shortage of foster care parents and the growing population of children in the system, citing the opioid epidemic as a major contributor, and then requests a change to federal rules to allow agencies to deny qualified parents in the name of religious freedom.

“The decision by HHS to allow for taxpayer-funded discrimination is an affront to American values, jeopardizing the safety and protection of vulnerable children in South Carolina, and potentially across the country,” Oregon Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden said in a statement to The Intercept. “It’s appalling that the Trump administration continues to throw the interests of children out the window. There are foster kids sleeping in hotels and living in temporary shelters. To turn away qualified parents because of their religion, sexual orientation or gender identity and deny these kids a secure home is immoral.”

The episode bodes poorly for advocates of civil liberties and religious freedom alike, and opens the door for foster care agencies in other states and players at other HHS-funded agencies, including the offices for Medicare and Medicaid, National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among others, to discriminate in the name of religious freedom while keeping their federal funding.

The post Trump Administration Grants South Carolina Foster Care Agencies Authority to Discriminate Against Jewish and Muslim Families appeared first on The Intercept.

President Donald Trump has been reasonably condemned for attempting to trash the Constitution. But there’s only one active politician in America working to actually reverse a standing constitutional amendment.

He’s a freshman Democratic House member from Maryland’s 6th Congressional District.

David Trone was elected in 2018 to fill the seat of John Delaney, who seems to think that he’s running for president. Trone won a spirited primary with the assistance of $14.2 million in self-funded contributions and another $3.25 million in personal loans. This available fortune was generated from Trone’s personal alcoholic beverage empire. Total Wine, which Trone co-founded with his brother, is America’s largest privately owned retailer of beer, wine, and liquor, with 193 stores in 23 states. Trone served as president of Total Wine until December 2016 and is still listed as co-owner of the company on its website.

Total Wine is currently embroiled in a Supreme Court case that challenges the 21st Amendment, which ended Prohibition. In Tennessee Wine & Spirits Retailers Association v. Blair, Total Wine claims that Tennessee cannot impose a two-year residency requirement for obtaining a retail license to sell alcohol. This has proven a barrier for Total Wine and for Doug and Mary Ketchum, who recently moved to Tennessee after agreeing to take over a mom-and-pop liquor store in Memphis.

But the residency issue is a stalking horse for the question of whether states have the right to regulate alcohol sales within their borders. While the 21st Amendment is seemingly very clear on that, alcohol producers and retailers have persistently fought it. If the Supreme Court sides with Total Wine, state alcohol laws will have little or no force, making it easier for retail giants to dominate the sector and potentially roll back health and safety measures on alcohol in a drive for profit.

So you have David Trone, a proud member of the new Democratic congressional majority, trying to use a conservative judiciary to deregulate an industry so that his wine shops can pop up on every street corner in America.

Section 1 of the 21st Amendment, ratified on December 5, 1933, simply repeals the 18th Amendment, which ushered in Prohibition 14 years earlier. But Section 2 bans “the transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof.” In other words, all alcohol producers or distributors had to follow local laws in order to make legal sales. This was seen at the time as a compromise to allow “dry” counties or states to continue with their local preferences. (In fact, parts of Trone’s district were dry until recently.)

In this case, the Ketchums moved from Utah in July 2016 to open a wine shop in Memphis. The Ketchums’s daughter has cerebral palsy, and the weather in Tennessee was deemed better for her ailment. The Tennessee Alcoholic Beverage Commission was actually ready to approve the application; the state hasn’t really enforced the two-year residency rule for several years, and Tennessee’s own former attorney general once claimed that it’s “probably unconstitutional.”

But the Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association, a local trade association, threatened to sue the state for not adhering to the residency requirement. Tennessee’s law is actually even more restrictive: The initial license expires after one year, and applicants looking to renew must be residents for 10 years.

At the same time, Total Wine wanted to open two new outlets in Nashville and Memphis, which would have faced hurdles if the residency rule was newly enforced because a retailer’s directors and officers must all be residents (thanks to the lax enforcement, Total Wine already has a store in Knoxville). Total Wine, at the time still under Trone’s direction, argued that the 21st Amendment was in conflict with the so-called dormant commerce clause doctrine, which prohibits states from discriminating against out-of-state or foreign commercial enterprises.

In 2005, the court ruled that laws allowing in-state wineries to ship to local residents had to be available to out-of-state wineries as well, to conform to the Constitution’s delegation of interstate commerce to Congress. According to the ruling, even if Congress made no law specifically on wine sales, the very existence of the commerce clause prohibited restrictions.

But Congress did ratify the 21st Amendment, which gave exclusive regulatory rights over alcohol to the states. Therein lies the dispute.

The 6th Circuit Court of Appeals sided with Total Wine and threw out the residency requirement, further opening the loophole to the 21st Amendment first breached in 2005, from alcohol producers and products to retail businesses. The Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association appealed to the Supreme Court.

You could view Tennessee’s residency requirement as protectionism to prevent outside companies from doing business in the state. After all, it’s not like Tennesseans, in the home of Jack Daniels whiskey, are forced to do without liquor; they’re just restricted from purchasing from out-of-state sellers.

But Sandeep Vaheesan of the Open Markets Institute argues that opinions about the regulation are besides the point; in plain fact, states have been empowered with oversight over alcohol. The 21st Amendment “sought to ensure that alcohol would still be subject to close public oversight and gave this power to the states to structure markets for alcohol in accordance with local preferences,” Vaheesan and John Laughlin Carter write in an amicus brief to the court.

Vaheesan and Carter believe that the 2005 ruling “violated the plain language of the Twenty-First Amendment” and worry about the broader degradation of states’ ability to regulate alcohol, particularly based on a judge’s prerogative to deem a regulation protectionist. “States should have the authority to structure commerce in alcohol to promote a range of public ends, including but not limited to the protection of public health, the promotion of the responsible use of alcohol, and the maintenance of decentralized markets with many distributors and producers of alcohol,” they write.

Much more is at stake than whether the Ketchums have to wait two years to open a liquor store (indeed, since the Ketchums moved to Tennessee in July 2016, they could legally procure a state liquor license today, at least for the first year). If the ruling is broad enough, it could nullify retail bans on direct-to-consumer wine shipping. That would allow Amazon or Walmart to sell wine over the internet.

More immediately, Total Wine would have fewer restrictions to expand its business from 23 to all 50 states. The national chain has already overrun states without residency laws and would almost certainly use its market power to dominate Tennessee and everywhere else. Ironically, the Ketchums, who teamed up with Total Wine in the lawsuit, may be at risk from Total Wine’s power if they prove victorious.

And if that succeeds, Total Wine and other giants can gain political power in the states, threatening other laws regulating the usage of alcohol. Whether by extrapolation from judicial precedent or brute force lobbying power, those laws could fall. Alcohol markets in the United Kingdom have been effectively deregulated, leading to high rates of intoxication among young people and a veritable public health crisis. Breaking the state regulatory apparatus could worsen alcoholism in America.

At the Supreme Court last week, in oral arguments held on the 100th anniversary of the original Prohibition amendment, several justices appeared skeptical of the residency requirement, with Justice Elena Kagan intimating that it is “clearly protectionist.” But Kagan and Justice Neil Gorsuch did seem to understand the slippery slope at play; Gorsuch wondered whether the next step would be to ask for license to “operate as the Amazon of liquor.”

Gorsuch added that “alcohol has been treated differently than other commodities in our nation’s experience,” and the 21st Amendment provided a barrier to an easy adjudication of the case. Attorneys for the Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association made similar claims about the amendment’s granting of near-total regulatory power over alcohol to the states.

With Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg absent and uncharacteristic silence from Chief Justice John Roberts, SCOTUSBlog called it “a hard case to handicap.” But the outcome matters enormously for Trone and the ability to extend his wine empire.

Total Wine has often used tactics designed to corner markets. The company has paid fines in Connecticut for selling wine and liquor below cost, a form of predatory pricing to gain market share and drive competitors out of business. Massachusetts accused Total Wine of the same tactic in 2016, but the company sued the state and won on appeal. In 2016, Maryland cited Total Wine for giving campaign contributions above state limits.

Through it all, Total Wine has continuously expanded across the eastern seaboard and the Southwest, and it ships wine wherever state laws allow. Where expansion has been curtailed, Total Wine has employed lobbyists and lawyers, suing Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland, and Massachusetts over its alcohol laws.

The midterm victory was Trone’s second attempt at a House seat; he unsuccessfully ran in 2016 for the seat vacated by Chris Van Hollen and now occupied by Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md. In 2018, he switched seats and ran in Maryland’s 6th, where residents mysteriously started receiving Total Wine circulars even though there are no outlets in the area.

Hannah Muldavin, communications director for Trone, told The Intercept to contact Total Wine directly for comment. A spokesperson for Total Wine replied that the company doesn’t comment on pending litigation.

Correction: January 23, 2019, 4:59 p.m.

A previous version of this story referred to 19th century oligarch Jay Gould as having served in the Senate. He did not.

The post The Monopolist in the House: Rep. David Trone’s Wine Company Seeks to Overturn a Constitutional Amendment appeared first on The Intercept.

When Kara Eastman pulled off a primary upset this past spring in Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District, a swing seat in the Omaha metro region, she did so with no help from the national Democratic party. Eastman, a social worker and first-time candidate running on an unapologetic left-wing platform, was competing against former Rep. Brad Ashford, who served for years in the Nebraska legislature and one term in Congress between 2014 and 2016.

Despite Ashford’s long track record of supporting abortion restrictions, pro-choice groups like EMILY’s List, Planned Parenthood, and NARAL Pro-Choice America opted to stay out of the race. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, or DCCC, elevated Ashford to their “Red to Blue” list, a signal of official party support for competitive races, and political action committees controlled by House leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Md., kicked in over $28,000 to Ashford’s bid.

Eastman, who embraced not only reproductive freedom but also policies like “Medicare for All,” tuition-free college, a $15 minimum wage, and increased gun control, struggled early on to compete. While her proposals and personal story were popular, finding donors was hard.

Yet by the time her primary rolled around, Eastman emerged the winner, raising close to $400,000 and benefitting from a flurry of late-stage media coverage. Using a new digital fundraising company to target customized groups of donors across the country — such as all Democrats who identify as social workers or those who back “Medicare for All” — Eastman’s team was able to change the trajectory of the race.

Her campaign credits Grassroots Analytics, an obscure tech startup that’s quietly shaking up the Democratic campaign finance world. Not a single article has ever been written about or even mentioned it, despite the company having aided some of the biggest upsets of the 2018 cycle, including Joe Cunningham in South Carolina, Lucy McBath in Georgia, and Kendra Horn in Oklahoma.

“Grassroots Analytics absolutely was what allowed us to be competitive in the primary and get on TV, otherwise there is no way we would have won,” said Dave Pantos, the finance director for Eastman’s campaign. “We were definitely not the mainstream candidate, and we didn’t have access to donor lists that more establishment candidates have.” Eastman ended up losing the general election, earning 49 percent of the vote, but has already announced that she’s jumping back in the fray for 2020.

Grassroots Analytics says it wants to level the playing field and to make it easier for candidates to run who don’t already have a built-in network of wealthy family, friends, and co-workers. Using an algorithm to clean and sort publicly available data spread across the internet, the company provides campaigns with customized lists of donors who they believe are most likely to support them. If you’re involved in the world of political fundraising, a thought has probably occurred to you just now: Wait, isn’t that illegal? Hold that thought.

Establishment groups like the Democratic National Committee, the DCCC, and EMILY’s List have largely given the firm the cold shoulder, despite its goals and the fact that it worked with 137 campaigns in the last cycle. Not even mainstream progressive organizations like Our Revolution or Justice Democrats would return Grassroots Analytics’s entreaties to work together.

Photo: Justin T. Gellerson for The Intercept

Danny Hogenkamp, the 24-year-old founder and director of Grassroots Analytics, wasn’t expecting to end up in this kind of business. He had no background in politics; he studied Arabic at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and assumed he’d end up doing foreign policy or refugee resettlement work after college.

But after graduating in 2016, with no job yet to speak of, he decided to go crash with some relatives in Syracuse, New York, where he was born, and try his hand in a congressional campaign. He enlisted with first-time candidate Colleen Deacon, a 39-year-old single mother who had worked as Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand’s regional aide in upstate New York. Deacon, who previously lived on Medicaid and food stamps, campaigned on putting herself through college with minimum wage jobs and student loans.

Hogenkamp was placed on the finance team, where he was charged with raising money and managing a team of 20 unpaid interns. It was there that he first encountered the opaque world of political fundraising — a world that even many organizers, pundits, and journalists can hardly grasp.

“I had no idea what campaigns were like, and it turns out that literally what candidates actually do to raise money, unless you’re really well-connected and famous, is sit in a room and call rich, old people to beg for $1,500, $2,000, or preferably [the federal maximum] of $2,700,” he said.

To run a competitive House race, Deacon’s campaign knew it needed to raise between $1.5 million and $2 million. Syracuse is one of the poorer metropolitan areas in New York, and after the campaign exhausted all the local prospective donors it could think of, the next step was the big open secret in political campaigning: finding similar candidates in other states and races and then researching who donated to their campaigns. So, for example, Deacon staffers would search for similar candidates — like Monica Vernon, who was running for Congress at the same time in Iowa — and then try and track down the contact information for the donors listed on their Federal Election Commission reports.

“Our interns would literally just Google people and try to find their phone numbers,” Hogenkamp said. “But donors change their numbers all the time, and they’re hard to find.”

The whole thing was invariably slow and disorganized. “It was the stupidest process,” he said. “It’s not digitized; there’s no math; it’s just random and stupid.”

Hogenkamp, still pretty much an idealistic novice, was convinced that there had to be a better way, some obvious step he was missing. So, from his perch as a relatively high-level finance staffer on Deacon’s team, he reached out to everyone he could think of — like the DCCC, EMILY’s List, liberal consulting firms, and other politicians — to find out how to make this fundraising process easier. “No one had any good answers; they said, ‘Well, this is just how you do it,’” he said. Hogenkamp recalled Gillibrand’s team telling him about its personal wealthy contacts in New York and how fundraising for the campaign meant going to those people and asking each of them to go out and find 10 more donors within their own networks.

Eventually, Hogenkamp connected with David Chase, a Democratic political operative who was then managing the campaign for Rubén Kihuen in Nevada’s 4th Congressional District. Chase offered a bit of help: He had developed a very rudimentary tool to aid his team’s fundraising efforts.

“Using OpenSecrets, I built some product that allowed you to search through all the federal and state contributions,” Chase told The Intercept. “It was very simple — I don’t have any advanced technological skills — but I wrote a script that allowed you to upload a list and it spit back the stats on the amount of times someone had given to state races and their average contributions.” In other words, for someone looking to discover who had given $500 or so to multiple candidates, Chase’s tool provided a way to more quickly glean that information.

Chase explained his tool, and Hogenkamp realized that there was a lot more he could do with an idea like that. During college, he had interned at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, where he learned to model how likely students were to default on their student loans. “I just randomly had a background in R and Python and zero-inflated negative binomial regressions from my time at the CFPB, so it was really just serendipitous that I actually knew what to do,” he said. Following that conversation, Hogenkamp went back and recruited a bunch of Syracuse University computer science students to help him build out his vision.

The result was effectively what he calls a “cleaner” of publicly available data, scraped from across the internet, that analyzes and sorts information for more than 14.5 million Democratic donors over the last 15 years. The tool would generate lists of individuals most likely to support a candidate given shared characteristics and shared views — ranging from race and ethnicity to a passion for yoga or universal health care.

“We know where you live; where you used to live; what issues you care about; if you’re trending Republican or Democrat; what other kinds of candidates you like to support; and contact information” he explained.

The lists aren’t perfect or fully comprehensive. They exclude some websites for legal reasons, and when I asked to see my own donor profile, recalling a $25 donation I gave in college to an Ohio Democrat, Grassroots Analytics had no record of it, because I’ve never given above the $200 reporting minimum to a federal candidate, and only some states and localities disclose small-dollar donations. Had I donated $5 to Stacey Abrams’s gubernatorial campaign, by contrast, I would have shown up in their system.

Nevertheless, the tool offers candidates — especially insurgent and working-class ones who lack rolodexes of wealthy friends — a real window into what is arguably the most important part of any political campaign: early-stage fundraising. The unspoken rule of viability in federal campaigning is that if you haven’t amassed at least $250,000 by your first quarter financial report, you’re probably not a candidate who people will take too seriously. EMILY’s List, an acronym for “Early Money Is Like Yeast,” was founded precisely to help female pro-choice Democrats compete against men who have long received the bulk of political contributions from the heavily white and male political donor class. Yeast makes the dough rise.

Connor Farrell, the finance director for Abdul El-Sayed, a left-wing former candidate who ran for Michigan governor this past cycle, credits Grassroots Analytics with fast-tracking his campaign’s fundraising, allowing the team to target progressives and doctors across the country. (El-Sayed campaigned on his credentials as a physician and public health expert.) “The applications of this new tool were valuable for our call-time operation, building for events, and some digital solicitations,” Farrell told The Intercept. “Grassroots saved us enormous research time, while allowing us to pivot quickly to new avenues of research. For a bootstrapped campaign, saving time and being flexible in your finance department is critical.”

Photo: Justin T. Gellerson for The Intercept

Is Grassroots Analytics legal? And moreover, in the age when big tech companies are under fire for sharing personal information — not to mention Cambridge Analytica, the political consulting firm, hired by the Trump campaign in 2016, which gained access to more than 50 million Facebook users’ private data — is it ethical?

Depends on who you ask. Federal law prohibits “any information copied from” Federal Election Commission reports from being “sold or used by any person for the purposes of soliciting contributions or for commercial purposes.” Subsequent regulation prohibits “information copied, or otherwise obtained, from any [FEC] report or statement, or any copy, reproduction, or publication thereof” from being sold or used for soliciting contributions. But because these laws date back to before the advent of the internet, and campaigns across the country already scour through FEC lists for leads, Grassroots Analytics says it’s effectively just simplifying the process that hordes of interns and finance staffers already do every day when they set out to research donor prospects.

To comply with the legal prohibition, Grassroots Analytics bars its algorithm from scraping the FEC website and websites like OpenSecrets that aggregate data directly from the FEC. Instead, Grassroots Analytics collects campaign contribution data only from public record caches, newspaper articles, nonprofit reports, and secondary websites. However, there’s little question that most of the campaign finance information they do collect originated at some point from FEC reports.

The company, in other words, exploits an ambiguity in the law, which is whether they have in fact “obtained” information from FEC reports. How many layers removed does information have to be in the age of the internet to pass legal muster? In an advisory opinion produced at the request of Grassroots Analytics that was reviewed by The Intercept, an attorney with one of California’s top boutique firms specializing in political and election law determined that existing law, court cases, and the FEC’s enforcement history “provide no clear answer to this question.” But because Grassroots Analytics takes steps to omit FEC data and sites that aggregate directly from the FEC, the attorney hired to assess their legal status determined that the company has a “legally defensible” position that its products and services do not violate federal law and that in their expert opinion, the FEC, especially with a Republican majority, is unlikely to conclude that the firm or its clients are breaking the law.

“I obviously didn’t go into tens of thousands of dollars of credit card debt to get this thing going without getting extensive legal advice from multiple law firms,” said Hogenkamp. “I’m a little rash sometimes, but I’m not that stupid.”

But should donor information, even if it’s technically public, be made so easily accessible?

“They’re donor pimps, that’s all they are,” said one fundraiser. “If you don’t know people, if your staff doesn’t know people, then you actually shouldn’t run for office. You’re not actually a good candidate.”

Others shrug off the critics, saying that while the FEC and secretaries of state should work to clarify campaign finance rules in the age of the internet, including for political advertisements, right now it’s no secret that most campaigns utilize FEC data in some fashion for solicitation purposes. “Most people think it’s fine to use those lists to research people a little further, to get a better picture of their donor history, and then turn them into leads,” one senior finance director told me.

“I think part of the debate is that the folks who’ve traditionally run the finance side of our party tend to be a little older, more focused on relationships and identifying event hosts and bundlers,” said Chase, who now works for a Democratic consulting firm. “But I think from the last cycle or two, you’ve seen a pretty dramatic shift in the way our party raises money. Digital fundraising exploded, and with that came folks like Danny who said, ‘Well, maybe we can do some of this stuff better than the traditional way of just calling rich folks and trying to get nice checks.’”

The debate also stems partly from confusion over what Grassroots Analytics is or actually does. Some suspect they’re just farming out lists of rich people to clients and engaging in another disapproved practice that’s rampant in the campaign industry — taking donor data from one campaign to another. Trading rich donor contact information is also not unusual among senior finance staffers.

Hogenkamp understands the mistrust. “Don’t get me wrong: I’m so skeptical of everyone in this industry. I totally understand how very smart people would think we’re just some kids with a list of like a hundred thousand donors and that we just make money off that same list,” he said. “But it’s like, no, we have more than 14 million people.”

There is another data analytics company that bills itself as helping candidates (and nonprofits and universities) become more strategic in their fundraising efforts. RevUp, which promises to “revolutionize your fundraising,” was started in 2013 by a top Obama fundraiser and Silicon Valley investor named Steve Spinner. It’s a software company that works with both Republicans and Democrats, helping campaigns to analyze their existing social networks, like their email contacts or LinkedIn connections, to more efficiently find new prospects to hit up. (Grassroots Analytics also analyzes clients’ LinkedIn data for donor prospects.) In October, RevUp, which has won several campaign industry awards for fundraising and innovation, announced a new $7.5 million round of investment.

A key difference between RevUp and Grassroots Analytics is that the former doesn’t expand the universe of donor prospects beyond your own network — it just helps you navigate and analyze the contacts in your existing universe more efficiently. From one vantage point, that’s more respectful, and skirts the thorny questions of legality and ethics. From another, it doesn’t do much to change the problem of connected people hoarding access to connected people.

“At RevUp, we believe successful fundraising is all about respecting prospective donors,” Spinner told The Intercept. “Through our data analytics software, RevUp uniquely allows a candidate, staff, or volunteer to reach out to the right person, at the right time, with the right ask. Our mission is to expand the donor universe and grow the pie beyond the ‘low-hanging fruit’ — the 25,000 major donors that get constantly called.”

Photo: Justin T. Gellerson for The Intercept

When Hogenkamp first developed Grassroots Analytics, he hoped someone in the Democratic establishment would recognize the potential of this technology, buy him out, and give him the institutional support to make it grow. But despite his persistent appeals, almost no one would return his emails.

Yet while no groups would publicly associate with Grassroots Analytics, staffers for some major Democratic political organizations were discreetly referring their candidates to the company throughout the 2018 cycle. Two emails reviewed by The Intercept showed an EMILY’s List campaign operative connecting Grassroots Analytics to Sol Flores’s primary campaign in Illinois and to Veronica Escobar’s race in Texas. “Thanks again for all your work with all o[f] EMILYs List candidates,” they wrote.

Other emails showed Democratic consultants setting up deals with Grassroots Analytics, explaining that the DCCC would be the organization actually writing the check on behalf of their clients. (This was the case with Linda Coleman’s unsuccessful bid for Congress.)

The DCCC and EMILY’s List did not return multiple requests for comment. When the DNC rolled out its “I Will Run” program in April 2018, which was essentially a list of vetted technology companies they recommended campaigns to hire, DNC Tech Manager Sally Marx announced the committee had “surveyed the progressive tech ecosystem looking for tools that campaigns and state parties can use to upgrade their work.” Their list, the DNC said, was a “curated compilation of the best-in-class tools currently used by campaigns.”

RevUp was on there for recommended fundraising companies, but Grassroots Analytics was not. The DNC declined to make Marx available for comment, but in a statement provided by a spokesperson, the party committee claimed Grassroots Analytics “was not on our radar until recently. As we head into this cycle, we look forward to re-evaluating and potentially adding new vendors to our I Will Run marketplace.”

Spokespersons for Our Revolution and Justice Democrats also confirmed that they do not have relationships with Grassroots Analytics and have not referred their candidates to the company.

One person who did show an early interest and helped Hogenkamp break into the field was Molly Allen, a political consultant who runs the political action committee for Blue Dog Democrats. She met with him in 2017 and referred Grassroots to their first three clients.

“I’ve only met Danny a few times and haven’t formally worked with them more than a short-term one-off, so I can’t speak to their work in details, but Danny seems great and I respect his start-up idea and success!” wrote Allen in an email.

I asked Hogenkamp how he felt about his company breaking out by representing Blue Dogs, when they had envisioned being a fix to the barriers blocking progressives from running for office.

“It was weird, but I was desperate,” he said.

Over the course of the last two years, though, Grassroots Analytics has decided to work with anyone running in the Democratic caucus, a decision Hogenkamp says was made to avoid pitting themselves as arbiters of the left. (This could also just be a handy rationale to bolster their client lists and profit margins.) But Grassroots Analytics, Hogenkamp adds, does have some red lines for clients, saying they turned down someone last year who they felt had too strong of ties to charter school backers.

Photo: Justin T. Gellerson for The Intercept

But if this all could be started by a young person with barely any political experience, why hadn’t it been done before?

Multiple people interviewed for this article chalked the problem up to monopoly in the political industry and the disincentives to innovate that come with monopolies.

Sean Adler, a New York-based software engineer, said he ran into this problem when he tried to insert some innovation into campaigning four years ago. A friend of Adler’s had mounted a bid for Congress in New Jersey, and Adler, then 23 years old, started developing phone banking tools for the campaign’s volunteers. He ended up co-founding a company to sell the technology and called it Partic.

“I wrote the whole thing from scratch. We took the whole data file of voters, and it would distribute lists and show a script and do all sorts of custom assignments,” he explained. “But one thing that ended up being a bummer was the DCCC had their own thing they forced campaigns to use, so we ended up only getting the real scrappy campaigns, the real mega-underdogs.” Adler was referring to VAN, an omnipresent software company that provides what they describe as “an integrated platform of the best fundraising, compliance, field, organizing, digital, and social networking products.”

Adler built a host of new design features and capabilities to make phone banking more useable and successful than he found VAN’s technology offered. Partic worked with eight campaigns in the 2016 cycle, but has since ceased operations, citing the enormous barriers new companies face to compete effectively.

“No one can enter this market without a lot of connections, and that’s fair, but the customer base of this market also completely goes away every two years, so the only people who can sustain that are people who are already in it,” Adler told The Intercept. “I think I was too much of an idealistic liberal,” he continued. “I thought, ‘Oh sure, the Democratic Party might not be as technologically advanced as Google, but they certainly wouldn’t try to shut out people with better ideas and products in order to protect their friends.’ For the state of the world to change, people like Danny have to succeed. The establishment monopoly not only screws over local candidates no one has ever heard of, but it also screws over candidates at the very top.”

Ultimately, Hogenkamp says he wouldn’t mind being put out of business, citing the new bill introduced in the House this month for publicly financed elections.

“I sort of stumbled into this. I think the whole campaign fundraising system is stupid, and you know, if our country gets serious about publicly funded elections, I would so gladly shut down the business and go work in the State Department like I had planned,” he said. “I don’t care enough about this; the whole campaign finance system needs to be completely overhauled, but until that happens, the only way you’re ever going to do it is helping Democrats raise money to win competitive elections.”

The post A Democratic Firm Is Shaking Up the World of Political Fundraising appeared first on The Intercept.

Subscribe to the Intercepted podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, Radio Public, and other platforms. New to podcasting? Click here.

BuzzFeed or Buzzkill? This week on Intercepted: Longtime investigative journalist Michael Isikoff of Yahoo! News analyzes the BuzzFeed News bombshell report that Trump ordered Michael Cohen to lie to cover up a planned Trump Tower in Moscow. Robert Mueller is disputing the report and Isikoff offers his own critique of the story and what we know to be true thus far. Stephanie Kelton, the popular economist and adviser to the Bernie Sanders 2016 campaign, talks about Modern Monetary Theory, the lies told by Republicans and Democrats about deficits, and whether young workers will ever get Social Security benefits. Los Angeles public school teachers appear to have won some major victories as a result of their historic strike. We speak to Noriko Nakada, an 8th grade English teacher at Emerson Middle School in LA, and labor journalist Sarah Jaffe, who covered the strike for The Nation.

Transcript coming soon.

Correction: January 23, 2019, 1:50 p.m.

In a previous version of this episode, Jeremy Scahill misidentified Rep. Joaquín Castro as a possible 2020 presidential candidate. In fact, his brother, Julián Castro, is a possible 2020 presidential contender. The reference has been removed.

The post Donald Trump and the Media Temple of BOOM! appeared first on The Intercept.

NARVA, Estonia—If you haven’t heard of Narva, you might very soon. This small, mostly Russian-speaking city lies along Estonia’s boundary with Russia, separated geographically from its larger neighbor only by a partially frozen river. A 13th-century castle towers over passersby, while an intimidating medieval stronghold stares back across the river from the Russian side. A short walk away stands a monument to the late chess grand master Paul Keres, who was born here and lived through decades of Soviet occupation, but always attributed his success to the Estonian school of chess.

This city is also the epicenter of what could be an epic challenge for Western military alliances—what NATO calls the “Narva scenario”—one that would test the foundation underpinning the security partnership.

When Estonia regained its independence after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Narva became a border town. Street signs here are in Estonian script, official business is carried out in Estonian, and the country requires that anyone who becomes a citizen must speak the language. But Narva’s population remains overwhelmingly Russian-speaking and ethnically Russian, leaving a sizeable number ineligible for Estonian citizenship. Instead, many are either Russian citizens or stateless residents of Estonia, who possess gray “alien passports.”

[Read: Trump’s biggest gift to Putin]

All of that, Western security officials fear, makes it a prime target for Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin. Under the “Narva scenario,” NATO worries that Putin could try to claw Narva into Russia. Such a move would mimic Russia’s incursion into Crimea, a Ukrainian territory it annexed in 2014, and its efforts to sow unrest in eastern Ukraine. But a similar push into Estonia would have even farther-reaching consequences: Estonia is a member of NATO.

Such a situation would then be a test of NATO’s commitment to Article V of the Washington Treaty, the one-for-all, all-for-one provision that requires the 29 NATO members, including the United States, to come to the defense of other member states.