A maioria das informações coletadas por profissionais do planejamento urbano é um emaranhado de dados complexos e de difícil representação – muito diferente dos gráficos e tabelas simplificadas de jogos de simulação do tipo SimCity. Mas uma nova iniciativa da Sidewalk Labs, uma subsidiária da Alphabet, o conglomerado de empresas do Google, promete mudar isso.

O projeto, batizado de “Replica”, permite que órgãos de planejamento tenham acesso aos padrões de mobilidade de cidades inteiras. Assim como em SimCity, a ferramenta “fácil de usar” do Replica faz uso de simulações estatísticas para mostrar como, quando e onde as pessoas se deslocam dentro dos centros urbanos. É uma ferramenta promissora para os profissionais que trabalham com planejamento de transportes e ordenamento de uso do solo. Nos últimos meses, os órgãos do setor de transportes de Kansas City, Portland e Chicago se inscreveram no programa. Mas existe um porém: ninguém sabe exatamente de onde vêm esses dados.

Normalmente, os planejadores urbanos dependem de pesquisas e contagens volumétricas, procedimentos caros, demorados e com equipamentos muitas vezes antiquados. Já o Replica se alimenta de dados de localização de celulares coletados em tempo real. Como explica Nick Bowden, da Sidewalk Labs, “o Replica oferece um amplo leque de dados de deslocamento que são muito difíceis de se obter atualmente, como o número de pessoas em uma via expressa ou rede de ruas locais, o meio de transporte utilizado (carro, transporte público, bicicleta ou a pé) e o propósito da viagem (ida ao trabalho, às compras ou à escola)”.

Para fazer essas medições, o programa coleta e desidentifica a localização de telefones celulares, obtida junto a fornecedores não especificados. Por sua vez, esses dados anônimos alimentam uma série de simulações, criando uma população virtual que replica com precisão os padrões de mobilidade do mundo real, mas, como diz Bowden, “não revela os hábitos de cada pessoa no mundo real”.

O Replica surge em um momento de grande preocupação com o uso de nossas informações pessoais pelas empresas de tecnologia – e levanta novos questionamentos sobre a intrusão cada vez maior do Google no mundo físico.

Como a Sidewalk Labs tem acesso aos padrões de movimento das pessoas antes de gerar seu modelo artificial, não seria possível descobrir a identidade delas com base em seu local de trabalho ou descanso?No mês passado, o New York Times revelou como os dados de localização dos nossos smartphones são coletados por terceiros – muitas vezes com pedidos de permissão pouco claros ou até sem a autorização do usuário. No início de janeiro, uma investigação da revista Vice foi ainda mais longe e descobriu que operadores de telefonia vendem nossa localização a stalkers e caçadores de recompensas dispostos a pagar pela informação.

Em tal contexto, qualquer iniciativa de coleta em tempo real e comercialização de dados de localização vai deixar algumas pessoas ainda mais inquietas. “A questão da privacidade é uma grande preocupação. A localização de um telefone celular é uma informação extremamente delicada”, diz Ben Green, especialista em tecnologia urbana e autor do livro The Smart Enough City (não publicado no Brasil).

E essas preocupações não são apenas teóricas. Uma reportagem da Associated Press revelou que o site e os aplicativos do Google continuam rastreando os usuários mesmo após a desativação do histórico de localização. O portal de notícias Quartz descobriu que o Google rastreava usuários de Android usando os endereços de torres de telefonia mesmo com todos os serviços de localização desabilitados. A empresa também foi flagrada usando os veículos do Street View para coletar dados de localização de redes de internet sem fio de celulares e computadores.

É por isso que a Sidewalk Labs criou mecanismos consideráveis de proteção à privacidade – antes mesmo de começar a gerar sua população artificial. Todos os dados de localização já chegam à empresa anonimizados – através de métodos como generalização, técnicas de privacidade diferencial e até a exclusão de comportamentos singulares. Bowden explica que nos dados obtidos pelo Replica não estão incluídos os identificadores de dispositivo, que podem ser usados para revelar a identidade do usuário.

No entanto, certos planejadores urbanos e especialistas em tecnologia, embora elogiem os conceitos inovadores e elegantes do programa, continuam céticos com relação a esses mecanismos de proteção. Uma das questões levantadas é como a Sidewalk Labs define que informações permitem ou não identificar o usuário. Tamir Israel, especialista jurídico do Canadian Internet Policy & Public Interest Clinic, diz que é muito difícil impedir a reidentificação de certos dados. Como a Sidewalk Labs tem acesso aos padrões de movimento das pessoas antes de gerar seu modelo artificial, não seria possível descobrir a identidade delas com base em seu local de trabalho ou descanso? “Vemos muitas empresas aplicando métodos grosseiros de desidentificação para poder coletar dados. Mas já foi demonstrado que é muito fácil reidentificar dados de localização, muito mais do que outros tipos de informação”, afirma. “É muito fácil identificar quem vai dormir em tal endereço e trabalhar em tal escritório das 9h às 17h todo dia”, exemplifica. Um estudo que hoje é referência na área revelou que bastam quatro pontos de dados para reidentificar informações aparentemente anônimas.

Outra questão é a forma pela qual os fornecedores da Sidewalk Labs obtêm o consentimento dos usuários. Como demonstrado pelo tsunami de escândalos de quebra de privacidade do ano passado, muitas pessoas não sabem que seus dados estão sendo rastreados e vendidos para terceiros, anunciantes e programas como o Replica. “Precisamos ser mais rigorosos para garantir que a forma de obtenção do consentimento dos usuários seja condizente com o grau de confidencialidade dos dados coletados”, acredita Israel. O conceito de “consentimento” sempre foi definido em termos de uso vagos e genéricos, graças aos quais, aproveitando-se de intrincados detalhes técnicos, as empresas levam vantagem sobre usuários sem tempo de ler – e muito menos coompreender – o obscuro jargão das políticas de privacidade. A reportagem do New York Times descobriu, por exemplo, que “as explicações que as pessoas recebem antes de dar seu consentimento costumam ser incompletas ou enganosas”. Muitos aplicativos não informam claramente os usuários de que seus dados de localização podem ser compartilhados ou vendidos.

É difícil determinar se os dados foram obtidos com autorização dos usuários quando não se sabe ao certo de onde tais dados vieram. A Sidewalk Labs explica que os fornecedores do Replica são companhias de telecomunicações e empresas que agregam dados de localização de diversos aplicativos. “Monitoramos as práticas de nossos fornecedores para garantir que os códigos de conduta do setor sejam respeitados”, diz Bowden. “Não usamos dados do Google. Nosso amplo processo de auditoria inclui relatórios frequentes, entrevistas e avaliações para garantir que os fornecedores atendam os requisitos de privacidade e consentimento”, afirma.

Porém, como a origem exata dos dados não é revelada, não podemos saber se o Replica se alimenta de aplicativos não regulamentados que se aproveitam de políticas de privacidade imprecisas para rastrear e comercializar a localização dos usuários. Documentos públicos das cidades que compraram ou estão experimentando o Replica dão informações conflitantes sobre as fontes do Replica. Um comunicado do Departamento de Transportes de Illinois afirma que o programa recebe “dados de operadoras de telefonia celular, dados de localização de agregadores e dados do Google para gerar informações de mobilidade para uma determinada região”. Essa amostra de dados, acrescenta o documento, “não se limita a dispositivos com Android”, sendo “coletada durante meses seguidos, o que permite estabelecer padrões de deslocamento consistentes”. Em Portland, documentos da Câmara Municipal afirmam que os dados vêm de “telefones com Android e aplicativos do Google”. Funcionários do Gabinete de Transportes de Portland disseram à imprensa que uma parte dos dados de localização do Replica também podem vir de outras fontes ainda desconhecidas. Na ata de uma reunião de planejamento de transportes de Kansas City, alguém observa que o programa pode coletar dados “de coisas como o Uber e o Lyft”, e uma apresentação de slides do município afirma que a ferramenta “se baseia em dados do Google”.

O que está em jogo com o Replica é o potencial lucrativo de agregar dados sobre nossos deslocamentos e vendê-los aos órgãos públicos. Inicialmente, o programa foi vendido como uma ferramenta “de apoio ao desenvolvimento” de Quayside, a controversa “cidade inteligente” projetada para a orla leste de Toronto. Um porta-voz da Sidewalk Labs disse ao The Intercept que não há planos para levar o Replica à cidade, mas seus habitantes estão preocupados com os planos da empresa. Alguns veem o projeto como um exemplo de como as ferramentas e técnicas desenvolvidas pela Sidewalk Labs em Quayside poderiam ser aplicadas em outras cidades, mas sem gerar nenhum benefício econômico adicional para os moradores que produzem esses dados.

“O Replica é um exemplo perfeito do capitalismo da vigilância, que lucra com informações pessoais dos usuários de produtos que se tornaram parte de nossas vidas”, diz Brenda McPhail, diretora do Projeto de Privacidade, Tecnologia e Vigilância da Associação Canadense de Liberdades Civis. “A sociedade precisa refletir se deve continuar permitindo modelos de negócios baseados na exploração de nossas informações pessoais sem o nosso consentimento”, completa.

Tradução: Bernardo Tonasse

The post Empresa do conglomerado do Google quer vender dados de localização de milhões de telefones celulares appeared first on The Intercept.

Tragédias como as de Mariana e Brumadinho, no final das contas, saem barato para gigantes como a Vale. Basta acompanhar o mercado de ações.

O preço das ações de uma empresa na bolsa de valores, uma medida básica sobre o valor da própria empresa, é determinado por uma infinidade de variáveis. Uma, porém, se destaca: a expectativa em relação ao lucro da empresa, por parte dos investidores.

Imagine que uma empresa abre seu capital, oferecendo 100 ações. Se, por qualquer motivo, os investidores acreditam que essa empresa terá um aumento nos seus lucros, os papéis serão um bom investimento. Haverá um aumento na demanda por eles, e o preço unitário das ações sobe. Se por outro lado a expectativa é de queda no lucro da empresa, o público vai querer se livrar desses papéis, provocando uma queda no valor dessas ações.

Uma parte importante dos compradores e vendedores dessas ações é formada por aquilo que chamamos de especuladores. Isto é, indivíduos que não estão interessados no lucro da empresa daqui cinco ou 10 anos, mas estão em comprar as ações a um preço baixo e vender a um preço alto, sendo que tais operações podem ocorrer no intervalo de um único dia.

O valor da Vale já vinha em queda desde 2012. Mas, após a tragédia de Mariana, em novembro de 2015, a empresa – que é dona de 50% do capital da Samarco – perdeu 8% de seu valor de mercado em uma única semana. Naquele ano, aliás, a Vale foi a empresa de capital aberto que mais perdeu valor na bolsa brasileira, com uma queda da ordem de R$ 45,9 bilhões. Essa desvalorização se deveu não apenas à tragédia de Mariana, mas também à queda da cotação do minério de ferro no mercado global.

Mas, a partir de então, as ações da Vale voltaram a subir. No final de 2018, o valor de mercado da empresa fechou em R$ 263 bilhões, quase três vezes mais do que em 2014, antes do desastre, quando era de R$ 107 bi. Tudo leva a crer que deve ocorrer o mesmo com a tragédia de Brumadinho. Tudo será como antes.

Os cadáveres soterrados para sempre naquela lama têm importância mínima para a empresa e seus investidores. Eles são custos já precificados pelos investidores da Vale.

Torcida a favorDesastres como o de Mariana e Brumadinho são didáticos para contemplar a pior face do capitalismo brasileiro. Neles, se somam ganâncias privadas, a captura do legislativo estadual e federal por poderosos interesses econômicos e a brutal incompetência, corrupção e vistas grossas do poder público.

No meio disso tudo, no trajeto do rio de lama, há não “uma pedra” (como no poema do poeta de Itabira), mas uma flora e uma fauna – incluídos aí os humanos sem nome que, para os atores graúdos envolvidos, não têm importância comparável aos bônus de fim de ano distribuídos pela empresa.

Na economia de mercado, as empresas buscam mais lucros e menos custos. Tratar rejeitos de mineração (ou “dejeitos” no léxico presidencial) é custo, não é receita. Como alertou o professor Bruno Milanez, da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, as mineradoras cortam custos exatamente nessa área ambiental quando sua rentabilidade cai.

A única forma de forçar a empresa a se comportar é por meio da legislação e da pressão social. O público pode se recusar a comprar produtos de uma empresa poluidora, forçando o empresário a se preocupar com o meio ambiente. Esse cenário, porém, não vale para a Vale. Seu comprador é a China, que está a milhares de quilômetros de distância de Minas Gerais. E os governantes que podem puni-la dependem dos seus impostos para pagar os funcionários públicos – o governo de Minas, em especial, está em situação falimentar e não pode abrir mão desse dinheiro.

Segundo dados divulgados pela própria Vale, no primeiro semestre 2018, a empresa pagou R$ 676 milhões em tributos para o governo de Minas, além de ter realizado compras da ordem de R$ 4,9 bilhões – 77% de empresas daquele estado (R$ 3,8 bi). Em 2018, o minério de ferro respondeu a 8,4% das exportações brasileiras – é o terceiro produto mais importante, atrás apenas da soja e do petróleo – e a 30% das de Minas Gerais, o principal produto de exportação do estado. Em 2017, a participação do ferro foi ainda maior: 34% das exportações de Minas.

Ainda que a economia dos mineiros seja bastante sofisticada, especialmente para os padrões brasileiros, é evidente que a mineração é ainda muito importante para sua economia. E poder econômico se traduz sempre em poder político.

Precisando desses recursos e dos empregos diretos e indiretos gerados por projetos da Vale, políticos são incentivados a atender aos desejos dessa empresa gigantesca, inclusive facilitando a concessão de licenças ambientais ou fazendo vista grossa para irregularidades.

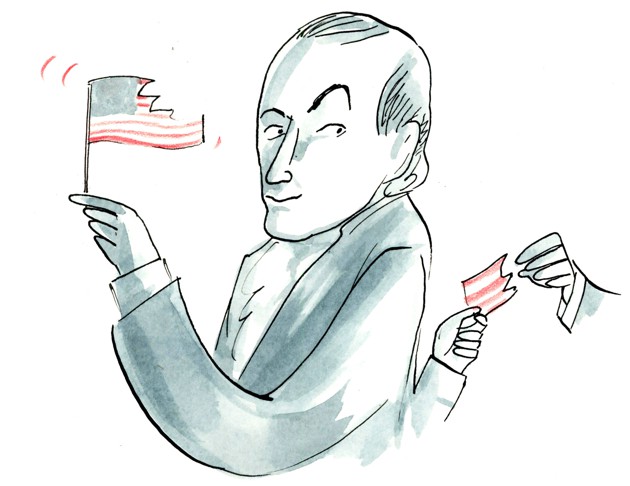

Nas eleições de 2014, por exemplo, a Vale “doou” quase R$ 30 milhões para campanhas de deputados federais, notadamente de Minas, Bahia e Pará. Tais doações se dividiram entre PMDB (R$ 13,8 mi), PSB (R$ 5,7 mi), PT (R$ 4,3 mi), PSDB (R$ 3,6 mi) e PP (R$ 1,7 mi). Isso deixa claro que o poder econômico da empresa irriga quase todo o espectro político brasileiro.

Na Assembleia de Minas, o deputado tucano João Vítor Xavier tentou aprovar um projeto que endurecia as regras para liberação de barragens das mineradoras. O texto, amplamente discutido com técnicos e representantes da sociedade civil, foi derrotado, em favor de um projeto virtualmente escrito pelas próprias mineradoras.

Num mundo hipotético – que em nada lembra o Brasil, felizmente –, uma empresa rica pode simplesmente subornar os agentes envolvidos no processo. Desde um simples fiscal de um órgão público, a um juiz encarregado de alguma demanda de seu interesse, passando pelo governador ou presidente. Uma hipótese remota.

É hora de comprar?Nas páginas especializadas, já há matérias do tipo “É hora de comprar ações da Vale?” Não sou trader, mas eu diria que sim. Afinal, já sabemos que as punições são leves em termos monetários (R$ 250 milhões de multa ambiental, como se diz pela avenida Paulista, é peanuts) e ninguém vai para cadeia (ninguém graúdo, pelo menos).

O que preocupa mesmo os compradores de suas ações é o apetite dos chineses por minério de ferro.

E só.

The post Os mortos de Brumadinho custam barato para a Vale. O que importa mesmo é a China. appeared first on The Intercept.

#RedforEd, the national teacher-led movement that started last year, continues to flex its muscles. On the heels of a successful six-day strike in Los Angeles, teachers in Virginia, Colorado, and elsewhere in California are voicing their demands for better working conditions, and, in some cases, threatening to strike.

On Monday, thousands of public school teachers flooded into Richmond, Virginia, for a one-day demonstration to pressure state lawmakers to increase funding for public education. The Richmond day of action was organized by a grassroots educator group, Virginia Educators United. It came after about nine months of planning, according to a Virginia Educators United spokesperson, and was backed by an “independent coalition” of stakeholders who support public schools, including union members, non-union members, educators, parents, administrators, and policymakers. Like the teacher uprisings in other states, supporters wore red in solidarity.

The teachers’ demands for increased funding come amid a steep drop in resources over the last decade. According to the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis, a Virginia think tank, per-pupil state funding for the 2018-2019 school year was 9.1 percent lower in real dollars than in 2008-2009.

The march garnered local and national teacher union support. Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, marched in Richmond on Monday alongside Lily García, president of the National Education Association.

Greetings from Richmond, Virginia, where an enormous crowd of thousands of teachers marched to the state capitol today to demand higher pay and school funding. #Red4Ed #redforedva #VirginiaEducatorsUnited #RedForEd

Here’s @rweingarten and @Lily_NEA leading the charge: pic.twitter.com/9y3a1HCvbN

— Graham Vyse (@GrahamVyse) January 28, 2019

“Our folks, we’re not big in Virginia, but we’re mighty, and we have three or four very active locals that have been working closely with the Virginia Educators United,” said Weingarten in an interview Monday afternoon. “Virginia is a pretty rich state, but actually spends about a billion dollars less in education than it did before the recession, which means its priorities need to be reordered.”

Weingarten said the last straw for many Virginia educators was seeing how readily lawmakers were able to come up with a “bountiful set of tax breaks” for Amazon to open its HQ2 in the state. If the state can competitively invest in business development, the teachers say, it should be able to invest in its schools and teachers. According to data from the NEA, Virginia ranks 34th nationally when it comes to teacher pay, with the average teacher earning $51,049.

Virginia’s Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam expressed support for the rallying teachers.

Wonderful to see so many Virginia educators raising their voices today #RedforEd https://t.co/gVCz1OWSEz

— Ralph Northam (@GovernorVA) January 28, 2019

About 1,670 miles west, in Denver, teachers are also preparing to go on what would be their first strike since 1994. While the strike was scheduled to take place on Monday, last week, Denver’s public school district requested state intervention, a move that could delay the strike for up to 180 days. Democratic Gov. Jared Polis has 14 days to decide if he will intervene, and his office has so far said he is undecided. If the state intervenes, Polis could call for a neutral fact-finder to assist in negotiations, or offer resources like arbitration or mediation. A strike in the middle of state intervention would be illegal, and teachers, guidance counselors, and nurses could face financial penalties and even the revocation of their licenses.

Lisa Calderón, a Denver mayoral candidate, urged Polis to stay out of the situation. “This is not a state issue, this is a local workers’ issue,” she said recently.

The Denver school district and union are at odds over teacher pay, as well as the size of bonuses for educators who work in schools where there are high levels of poverty among students. Denver educators are also highlighting the fact that administrative spending remains much higher in their city than in other parts of the state. Throughout 2018, there were signs of growing teacher militancy in Denver, and many parents, community members, and teachers began talking about the likelihood of a strike months ago. This past April, thousands of teachers descended on Denver, the state capital, to call on lawmakers to increase funding for public education. These demonstrations weren’t technically strikes (educators called them “walkouts”), as most school districts closed down beforehand in support of the teachers.

Teacher pay in Colorado ranks 31st in the country, and last year, the average educator earned just under $53,000, according to the state’s education department. Pay can vary widely across Colorado, with some districts averaging salaries above $70,000 and others with pay closer to $30,000. Last year in Denver, the average teacher pay (before bonuses) was $50,757.

In Northern California, the Oakland Education Association has called for a four-day strike authorization vote to begin Tuesday. Oakland educators, like their counterparts in LA, have been calling for smaller class sizes, more school nurses and counselors, and higher pay. They have been working without a contract since July 2017. In 2010, Oakland teachers went on strike for one day, and in 1996, they took the streets for 26 days.

Los Angeles teachers returned to work last Wednesday after a six-day strike, their first labor stoppage since 1989. Following the strike, 81 percent of United Teachers Los Angeles members voted to ratify their new contract, which includes new caps on class sizes and commitments to hire more nurses and librarians. The union also won a commitment from the Los Angeles Unified School District to develop a plan to reduce the number of standardized tests and explore limits on charter school growth, a big point of contention in the strike. Teachers also agreed to salary increases of 6 percent, which is what the district had offered prior to the strike.

The post Coming Off LA Strike Victory, a New Wave of Teacher Protests Takes Hold appeared first on The Intercept.

Rep. Yvette Clarke, D-N.Y., said that what she saw Monday morning while accompanying a New York immigration activist to his mandated check-in at the New York field office of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement left her with serious concerns about the agency’s secrecy and the way it treats the people it summons to its offices.

“It is very clear to me that there has been some skirting of the law, that the free flow of the public has been obstructed arbitrarily and unilaterally to create a pressurized environment in which human rights could be violated,” Clarke told the immigration activist’s friends and supporters at Foley Square, outside the federal building where the ICE check-in had taken place.

“It is very clear to me that there has been some skirting of the law, that the free flow of the public has been obstructed arbitrarily and unilaterally to create a pressurized environment in which human rights could be violated.”Clarke was accompanying Ravi Ragbir, the executive director of the New Sanctuary Coalition of New York City, whose attempted deportation by ICE a year ago during a check-in generated a massive street protest and a strident condemnation from the federal bench. Ragbir has several ongoing legal proceedings — including a First Amendment lawsuit alleging that ICE is targeting him for deportation based on his political speech — and federal courts in both the 2nd and 3rd Circuits of the U.S. Court of Appeals have issued stays forbidding ICE from deporting him until those proceedings are resolved.

Even so, Ragbir’s supporters weren’t entirely sure that ICE officials wouldn’t attempt to deport him anyway, and so they asked elected officials, including Clarke and current as well as former members of the New York City Council, to escort Ragbir when he kept his appointment at 26 Federal Plaza in lower Manhattan.

Elected officials have joined Ragbir for many of his ICE check-ins in recent years. While there’s no telling whether their presence has made a difference in his treatment, it’s done a great deal to shine a public light on the quotidian workings of the deportation bureaucracy.

When Ragbir attended a check-in in 2017, then-City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito was moved to tears by her conversations with mothers and children waiting without legal representation for meetings that could end in deportation. City Council Member Jumaane Williams called the spectacle “the most un-American thing I’ve seen.”

The City Council members were ordered to leave the hallway afterward by a man who, though he would not identify himself at the time, proved to be Scott Mechkowski, who as deputy director of ICE’s New York field office oversaw the attempted deportation of Ragbir last year. According to Ragbir’s First Amendment lawsuit, Mechkowski later told Ragbir’s lawyers that he still felt “resentment” over the encounter, naming Mark-Viverito and identifying Williams as “that guy from Brooklyn.”

In the interval, ICE has changed its policy, restricting access to the ninth-floor waiting room where people present themselves to find out whether they are being deported. Sara Gozalo, an organizer with the New Sanctuary Coalition, which organizes volunteers to accompany people to their ICE check-ins, said the restrictions began in the summer of 2017. “Their excuse was capacity issues,” Gozalo said, “but I personally accompanied people when the waiting room was empty, and was told I couldn’t go in.” Next, she said, ICE began denying family members entrance to the waiting room, making them wait three floors below in the sixth-floor cafeteria. “I’ve been with people just waiting in the cafeteria for hours, and they don’t know anything until they get the phone call saying their spouse is being deported,” Gozalo said. (ICE did not respond to emailed questions.)

Barring family and supporters from the waiting room isn’t just cruel to people facing difficult circumstances, Gozalo said. “It’s a way for ICE to continue doing their work in the shadows, like secret police,” she said. “It’s much easier to detain someone when nobody’s watching. You don’t have to account for what you’re doing, or deal with a family breaking down, or acknowledge all of the damage you’re doing.”

“It’s a way for ICE to continue doing their work in the shadows, like secret police. It’s much easier to detain someone when nobody’s watching.”When Ragbir took the elevator to the ninth floor this morning, he was accompanied by his lawyers; his wife, Amy Gottlieb; and Clarke. Outside the waiting room, an officer in a Department of Homeland Security uniform, who refused to identify himself beyond the first name “Matt,” informed the group that they had been instructed specifically that only Ragbir and one of his lawyers, Alina Das, would be allowed in. “The wife can’t go in,” the DHS officer said.

Das asked whose order the officer was enforcing, and whether she could speak to him. The officer disappeared briefly, then returned and reiterated the order: The lawyer and the client could go in. Ragbir’s wife and the elected officials supporting him could not. As for the request to discuss the matter, the DHS officer said the ICE supervisor wouldn’t speak to Ragbir’s entourage. “He says he doesn’t have to talk with you,” the DHS officer said of the person giving the orders.

“That’s not true,” responded Clarke, who was recently named to the House Homeland Security Committee, now controlled by fellow Democrats. Clarke eventually made it past the guards, where she began pressing ICE officials to justify the ban. A delegation of current and former City Council members, including Williams and Mark-Viverito, soon joined the delegation on the ninth floor, but were again refused access by the Homeland Security officer.

“I remember last year, it was supposed to be civil, and it wasn’t civil,” the officer said, presumably referring to the street protest that attempted to block Ragbir’s unlawful deportation last January. “So I’m being pre-emptive.”

If the officer remembered some members of the delegation, they remembered him as well. Rhiya Trivedi, one of Williams’s defense lawyers in his trial on obstruction and disorderly conduct stemming from last January’s protest, recognized the officer from the hours of video of the protest she reviewed in preparation for the case. “He’s all over the tape shoving people,” Trivedi said.

After a quarter-hour or more, Clarke emerged into the hallway to announce that after her conversation with ICE officials, Gottlieb and the elected officials would be allowed into the waiting room. But she was quickly countermanded by the Homeland Security officer, and the stand-off continued until Ragbir and Das emerged from the meeting room. He was free to go, but must check in again in six months.

Back downstairs, Clarke said she found the entire episode troubling.

“I observed what I believe are a number of unilateral policies that aren’t necessarily in law or statute that we’ll be reviewing,” she said. “I am not casting aspersions on the workers here at all; they are simply following instructions. I found it interesting that in the back and forth about the public space, a call was made to Washington for guidance. So we know where these unilateral decisions are coming from, and it is now my responsibility, along with my colleagues, to get this right. Every elected official here should have the right to be by Ravi’s side observing the governance of this place. Amy, his wife, deserves to be by his side during this time of trial.”

Clarke, who was returning to Washington immediately, said her first order of business would be to speak with the new Democratic Homeland Security Committee chair “about the policies, practices and procedures in respect to removal, due process, and public accommodation for those who have to utilize the services of the Department of Homeland Security.”

Looking drained after the morning’s events, Gottlieb, Ragbir’s wife, said the new rules are needlessly cruel. “If there’s no public safety reason to not have people in there, why do this, except with the intention to really dehumanize?” she asked. “ICE refuses to be subjected to any oversight, and we’re going to continue to do everything we can to expose that.”

The post A Member of Congress Tried to Go to an Immigration Activist’s ICE Check-in. ICE Tried to Block Her. appeared first on The Intercept.

Today in Silicon Valley: privacy glitches and starvation optimization. A rogue bug with the video-calling app FaceTime can lead iPhone users to listen, and even watch, calls before they are answered. Apple is quickly patching up the glitch, but it validates festering paranoia that technology can’t be trusted. The en vogue trend in Silicon Valley is extreme dieting that can supposedly hone productivity, but it could ultimately reinforce the potentially dangerous idea that all personal choices should be in service of accomplishing more work.

Genetically, humans are nearly identical to chimpanzees. That has led scientists to wonder about a major way in which we differ from our biological twins: violence. Humans the world over are far less violent within their communities, and one theory posits that the difference could in fact be evolutionary; that killing violent individuals over time played a key role in how we tamed ourselves.

White Christians have long used religion to rationalize bigotry and racism. That unsavory history, which includes supporting slavery and propping up Jim Crow laws, was long ago, but the writer Jemar Tisby suggests in his new book, The Color of Compromise, that white Christians still have a lot to do to reckon with the racism in their ranks. It’s a clarifying attempt by Tisby, who is black and Christian, to reach and speak to his white counterparts in a way that they’ll accept and understand.

Evening Reads

(Jeff Chiu / AP)

Was gym class a traumatizing part of school that still brings back shivers about that one particularly menacing bully? New research backs up what all too many of us already know: P.E. is kind of the worst:

Analyzing data out of the state’s Texas Fitness Now program—a $37 million endeavor to improve middle schoolers’ fitness, academic achievement, and behavior by requiring them to participate in P.E. every day—the researchers concluded that the daily mandate didn’t have any positive impact on kids’ health or educational outcome. On the contrary: They found that the program, which ran from 2007 to 2011, actually had detrimental effects, correlating with an uptick in discipline and absence rates.

→ Read the rest.

Tell us: What was your childhood P.E. experience like? Write to us at letters@theatlantic.com, and we may feature your response on our website and in future editions of The Atlantic daily.

(Leonhard Foeger / Reuters)

Since at least The Jetsons, people have been eyeing a future in which flying cars zip us around to work and back. But there’s a reason that the technology has proven elusive:

Cities aren’t about to let hastily trained pilots commandeer thousand-pound machines and human passengers. The alternative, which is to let autonomous pilots commandeer thousand-pound machines and human passengers, is no more likely. If the world has learned one thing about autonomous technology in the past decade, it’s this: Autonomy is hard. It’s really, really hard. Even self-driving advocates admit that in 2018, the hype around driverless cars came “crashing down.”

→ Read the rest.

(Shizuo Kambayashi /AP)

Our partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing urban dwellers around the world. Gracie McKenzie shares today’s top stories:

Could California’s ambitious but troubled high-speed rail project ease the state’s housing crisis? According to a new study, proponents should look to Japan—where bullet trains lowered housing prices.

“In lieu of gifts, please make a down payment on our new home.” When tying the knot, many couples realize they don’t want more things—so they’re asking friends and family to chip in for something bigger.

Uber has promised to reduce road congestion. But David Zipper argues that its new rewards program—which offers upgrades and free rides to frequent riders—will do the opposite.

Keep up with the most pressing, interesting, and important city stories of the day. Subscribe to the CityLab Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

If the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, can run for president in the already crowded 2020 Democratic field, why shouldn’t the mayors of New York and Los Angeles? After all, each city is bigger and more complicated than plenty of states. But there’s just one thing that Bill de Blasio, who’s not ruling out a race, and Eric Garcetti, who just did, ought to remember about the last time the mayors of the Big Apple and the City of Angels decided they were best suited to topple a controversial Republican president: It didn’t turn out so good.

The year was 1972, and Richard Nixon looked vulnerable. Mayor Sam Yorty of L.A.—a conservative Democrat known as “Travelin’ Sam” for his peripatetic publicly financed travel—had spent nearly half his time away from his city in the last half of 1971 before launching a quixotic campaign in which he sought to out-Nixon Nixon on law and order. Yorty complained that his hometown was “an experimental area for taking over of a city by a combination of bloc voting, black power, left-wing radicals, and if you please, identified communists.”

Yorty received the backing of William Loeb, the extreme right-wing publisher of the Manchester Union-Leader newspaper in New Hampshire, who thought Nixon had gone soft on Vietnam. But Yorty won just 6 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire primary, never got any traction, and dropped out of the race just before the California primary, begging voters to support Hubert Humphrey instead of the “radical” George McGovern, who would become the party’s nominee.

[Read: How to run for president while you’re running a city]

John V. Lindsay’s campaign started out with more promise. The charismatic, patrician Republican who had walked the streets of Harlem to keep the peace when other cities burned in the 60s switched his party registration in 1971 to mount a campaign that proclaimed, “While Washington’s been talking about our problems, John Lindsay’s been fighting them.” No less a hardened cynic than Hunter S. Thompson professed to be impressed.

“If you listen to the wizards, you will keep a careful eye on John Lindsay’s action in the Florida primary,” Thompson wrote in Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72. “Because if he looks good down here, and then even better in Wisconsin, the wizards say he can start looking for some very heavy company … and that would make things very interesting.” And if nothing else, Thompson hoped, the potential presence of both Lindsay and Ted Kennedy in the race might turn that summer’s Democratic Convention in Miami “into something like a weeklong orgy of sex, violence and treachery in the Bronx Zoo.”

But despite a cadre of loyal campaign aides that included a young Jeffrey Katzenberg and the speechwriter turned journalist Jeff Greenfield—and despite spending half a million dollars in Florida—Lindsay finished fifth, with just 7 percent of the vote.

[Read: Bill de Blasio and Gavin Newsom may give restrictionism new life]

“A disgruntled ex-New Yorker hired a plane to fly over Miami with a sign reading ‘LINDSAY MEANS TSURIS,’” which is Yiddish for trouble, Greenfield recalled in an email this week. The Brooklyn Democratic leader Meade Esposito, still contemptuous of the mayor’s party switch, declared, “Little Sheba better come home,” a reference to the popular Broadway play in which a forlorn housewife pines in vain for her lost dog.

But Lindsay pressed on to Wisconsin, and Sam Roberts, who covered the campaign for the New York Daily News, still recalls “the mixture of hope and desperation.” Lindsay’s poll numbers were in the gutter, so to build momentum, he adopted a new slogan: “The switch is on.”

“I remember naively buying into the optimism,” Roberts remembers. “I wrote a story for the Daily News that Wisconsin was not likely to be Lindsay’s last primary. As the story was transcribed in New York, the word ‘not’ was dropped. When it was published, I must have seemed prescient. The switch was on all right, but to other candidates. Lindsay ran sixth. The next day, he dropped out of the race.”

[Read: New York Mayor John Lindsay. Remember him?]

The political world is different today, of course. So Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend may dream of presidential glory—and his big-city counterparts, including former Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York, can, too. But the track record is not encouraging. Remember President Rudy Giuliani? Andrew Johnson, Grover Cleveland, and Calvin Coolidge were all mayors, but all first held other higher offices before winning the White House. Maybe, Greenfield suggested, that’s because the job of mayor “is seen in terms of picking up garbage and fixing the streets.” On the other hand, in Donald Trump’s Washington, that might be just what America needs.

Dixie Lambert has lived in the small fishing village of Cordova, Alaska, for 36 years. She knows almost everyone in the community—most of them U.S. Coast Guard employees and their families. During the 35-day shutdown, Lambert observed how many of these furloughed families struggled to make ends meet, so she began soliciting public donations at the local grocery store.

The filmmaker Derek Knowles, who was in the area filming another documentary project, met Lambert and was immediately struck by her personality and spirit. “She knew everyone who came into the store and transformed the grim backdrop of the shutdown into an occasion for good-humored action,” Knowles told The Atlantic. He decided to film Lambert for the better part of a day as she provided Cordovans with assistance buying groceries. “I felt like I got a window into Cordova itself and the power that can come from a genuine community, where everyone knows one another and cares for his or her neighbor,” said Knowles.

Alaska has one of the highest per capita rates of federal employees in the nation. As a result, it was hit especially hard by the economic effects of the shutdown. Even though the government has now temporarily reopened, Knowles said that many residents of Cordova are anxious that the deal won’t last long.

“We’re not even trying to guess what will happen next,” Lambert recently told Knowles.

It’s Tuesday, January 29. The State of the Union, which would have been broadcast tonight, has been rescheduled for February 5. Democrats have tapped a familiar name—the former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams—to deliver their rebuttal.

President Donald Trump’s longtime friend and informal adviser Roger Stone also pleaded not guilty to charges of obstruction and witness tampering brought in connection with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s probe.

Trump Eyes Venezuela: Trump has threatened to use military force against a country before. But now he’s surrounded by advisers who actually believe in regime change—most notably John Bolton, who could be the deciding force in whether the Trump administration pursues military action in Venezuela.

Negotiation Station: Russian officials reportedly tried to make a deal last year with North Korea, offering the country a nuclear power plant in the midst of ongoing U.S.-North Korea nuclear negotiations. Reports of the secret proposal come shortly before a second summit between President Trump and Kim Jong Un, currently planned for next month.

Signs From the Shutdown: Though federal workers have returned to work, the shutdown underscores just how unstable many Americans are financially. Vann R. Newkirk II writes that while the shutdown might have ended, the structural inequalities it exposed—including wage stagnation, an ongoing savings crisis, and a threadbare safety net—still persist.

A 5G Cold War: As the White House prepares to host Chinese officials for trade talks on Wednesday, the Department of Justice has unsealed its indictments of the Chinese technology giant Huawei, which allege that Huawei engaged in industrial espionage against American companies like T-Mobile. The implication of the indictments?: “In 2019, you can’t separate mobile technology from national security,” writes Alexis Madrigal.

Green No Deal: Democratic progressives have recently rallied around a Green New Deal. Here are seven reasons Democrats probably still won’t pass it.

Striking Teachers: Hundreds of teachers rallied in front of the Virginia state capitol yesterday demanding higher pay, continuing an unprecedented year of labor activism for teachers.

— Olivia Paschal and Madeleine Carlisle

Snapshot

A migrant man, part of a caravan of thousands traveling to the United States from Central America, loads his belongings on top of a van during the closing of the Barretal shelter in Tijuana, Mexico. Shannon Stapleton / Reuters

Ideas From The AtlanticAlexandria Ocasio-Cortez Understands Politics Better Than Her Critics (Shadi Hamid)

“This focus on shifting the contours of the national debate is sometimes referred to as expanding the ‘Overton window.’ It is altogether possible that Ocasio-Cortez doesn’t think that a 70 percent marginal tax rate is realistic in our lifetime—she might not even think it’s the best option from a narrow, technocratic perspective of economic performance—but it doesn’t need to be.” → Read on.

Why Flying Cars Are an Impossible Dream (Derek Thompson)

“Instead of accepting defeat, the mobility-tech world is shifting its laser beam of optimism from self-driving Earth taxis to self-driving air taxis.” → Read on.

Blame Democrats for the State of the Union Circus (Daniel Foster)

“The first State of the Union address—George Washington’s in 1790—was just 1,089 words. That’s shorter than this essay … Historically, it has been Democratic presidents who have liked the sound of their own voice best.” → Read on.

Why Tom Brokaw’s Comments About Assimilation Were Wrong (Reihan Salam)

“If the yardstick for successful assimilation is whether an immigrant speaks English, has a diverse group of friends and loved ones that isn’t solely composed of co-ethnics, and is capable of supporting herself without relying on safety-net benefits or wage subsidies, there is no question that educated and affluent immigrants will be more likely to measure up than their disadvantaged counterparts. But is that because they’re working harder at assimilation, as Brokaw might have it, or because their disadvantaged peers have more to overcome?” → Read on.

◆ Democrats Weigh Whether Wall Street Money Is Still Allowed in 2020 (Emily Stewart, Vox)

◆ Who’s Afraid of Howard Schultz? Just About Everyone, and They’re Right to Be (Nick Gillespie, Reason)

◆ Kamala Harris’s Choices (Benjamin Wallace-Wells, The New Yorker)

◆ At Least 30 People Allege Abuse by This Baton Rouge Ex-priest: How One Survivor Turned His Life Around (Andrea Gallo, The Advocate)

◆ In Polarized Washington, a Democrat Anchors Bipartisan Friendships in Faith (Jack Jenkins, Religion News Service)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily, and will be testing some formats throughout the new year. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

The Atacama Desert in northern Chile is the driest place on Earth, a parched rockscape whose inner core supports zero animal or plant life. Only a few hearty species of lichen, algae, fungi, and bacteria can survive there—mostly by clinging to mineral and salt deposits that concentrate moisture for them. Still, it’s a precarious life, and these microbes often enter states of suspended animation during dry spells, waking up only when they have enough water to get by.

So when a few rainstorms swept through the Atacama recently, drenching some places for the first time in recorded history, it looked like a great opportunity for the microbes. Deserts often bloom at such times, and the periphery of the Atacama (which can support a little plant life) was no exception: It exploded with wildflowers. A similar blossoming seemed likely for the microbes in the core: They could drink their fill at last and multiply like mad.

Things didn’t quite work out that way. What should have been a blessing turned into a massacre, as the excess water overwhelmed the microbes and burst their membranes open—an unexpected twist that could have deep implications for life on Mars and other planets.

The Atacama has been arid for 150 million years, making it the oldest desert on Earth. Its utter lack of rain can be traced to a perfect storm of geographic factors. A cold current in the nearby Pacific Ocean creates a permanent temperature inversion offshore, which discourages rainclouds from forming. The desert also lies in a valley that’s wedged between the Andes Mountains on the east and the Chilean Coastal Range on the west. These mountains form a double “rain shadow” and block moisture from reaching the Atacama from either side. The desert’s driest point, the Yungay region, receives fewer than 0.04 inches (or 1 millimeter) of rain a year. Death Valley in California gets 50 times more rain annually, and even the driest stretch ever recorded there still averaged 0.2 inches a year.

[Read: Climate change is hurting desert life]

That’s why the recent rainstorms in the Atacama—two in 2015 and one in 2017—were so startling. They left behind standing lagoons, some of which glowed a lurid yellow-green from the high concentration of dissolved mineral. Nothing like this had happened in Yungay since at least the days of Columbus, and possibly much earlier. No one quite knows what caused the freak storms, but climate change is a likely culprit, as the cold sea currents have been disrupted recently. This allowed a bank of rainclouds to form over the Pacific Ocean. The clouds then plowed over the Chilean Coastal Range and dumped water onto Yungay and surrounding areas.

Five months after the June 2017 storm, a group of scientists led by Armando Azua-Bustos, a microbiologist at the Universidad Autónoma de Chile, and Alberto Fairén, a planetary scientist at Cornell University, visited the Atacama to sample three lagoons. They wanted to study the microbes that had gotten swept into them and document how well they were handling this precious influx of water.

Not very well, it turned out. As detailed in a recent paper, the scientists found that the majority of microbes normally present in the soil had been wiped out—14 of 16 species in one lagoon (88 percent), and 12 of 16 in the others (75 percent)—leaving behind just a handful of survivors. On a local scale, the rains were every bit as devastating as the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, which killed off 70 to 80 percent of species globally.

The scientists traced this massacre back to the very thing that allows the microbes to survive in the Atacama: their ability to hoard water. Under normal conditions, this miserliness pays off. But when faced with a glut of water, they can’t turn off their molecular machinery and say when. They keep guzzling and guzzling, until they burst from internal pressure. Azua-Bustos and Fairén’s team found evidence of this in the lagoons, which had enzymes and other organic bits floating around in them—the exploded guts of dead microbes.

Water in the Atacama, then, plays a paradoxical role: It’s both the limiting factor for life as well as the cause of local extinctions. And while the death of some bacteria and algae might not seem like a big deal, these microbes are actually famous in some circles as analogues for life on Mars.

We don’t know whether Mars ever had life, but it seemed like a promising habitat for its first billion years, with vast liquid oceans and plenty of mineral nutrients—not much different than Earth. One billion years probably wasn’t enough time for multicellular life to arise, but Martian microbes were a real possibility.

Starting around 3.5 billion years ago, however, our planetary cousin went through a severe drying-out and began to lose its water. Some was sucked deep underground, and most of the rest got dissected into H2 and O through various chemical reactions. Eventually these processes turned most of Mars’s surface into one giant Atacama Desert, forbiddingly dry and dotted with mineral deposits. NASA in fact uses the Atacama landscape to test rovers and other equipment for Mars missions.

But there’s an important wrinkle here. The great drying-out didn’t happen instantly; it took eons. And during the transition, when Mars was fairly parched but still had some liquid water, it experienced floods that would have made Noah blanch. We can see evidence of them on the surface of Mars today: The dry riverbed channels and alluvial fans that those floods left behind are the largest in the solar system.

This tumultuous state—a hyper-dry climate, punctuated by massive washouts—would have been catastrophic for life on Mars. The slow drying-out would have choked off the vast majority of microbes, grinding them into dust. Any that managed to pull through, scientists have argued, probably would have resembled those in the Atacama today: water-hoarders clinging to oases of mineral deposits in a vast red desert.

But if Martian microbes did resemble their Atacama counterparts, then the washouts probably finished them off, swelling them with water and bursting them like balloons. After a certain point, in other words, Mars might have been too wet to sustain the life that evolved there.

[Read: The search for alien life begins in Earth’s oldest desert]

It’s possible, of course, that a few lucky pockets on Mars escaped flooding entirely, allowing microbes there to survive until today. But if so, Azua-Bustos and Fairén point out, our current approach to finding these holdouts could be doomed to fail. NASA sent the famed Viking lander to Mars in 1976, for example, largely to search for life there. To this end, the lander scooped up several soil samples for analysis—and immediately doused them with water. Viking might have come up empty anyway, but given the Atacama results, it also might have killed off the very thing it was looking for.

What applies to Mars applies to other worlds as well. Over the next decade, several new space telescopes will expand the hunt for life beyond our solar system, to planets orbiting distant stars. Scientists are especially keen to find planets that have liquid water, since as far as we know, liquid water is essential to life.

But that statement might need qualification. Water can give life, certainly. As planets change, however, and life evolves in tandem, it can also snatch life away.

Twitter’s CEO, Jack Dorsey, doesn’t eat for 22 hours of the day, and sometimes not at all. Over the weekend he tweeted that he’d been “playing with fasting for some time,” regularly eating all of his daily calories at dinner and occasionally going water-only for days on end. In many cases, severe and arbitrary food restriction might be called an eating disorder. And while researchers are hopeful that some types of fasts may be beneficial to people’s health, plenty of tech plutocrats have embraced extreme forms of the practice as a productivity hack.

Dorsey’s diet was widely criticized on the website he runs, but Silicon Valley has an obsession with food that goes far beyond the endorsement of questionable personal-health choices. Intermittent fasting is a type of biohacking, a term that includes productivity-honing behaviors popular among Silicon Valley power players for their supposed ability to focus a person’s energy to work longer and more efficiently. To enhance themselves personally, tech leaders have adopted everything from specially engineered nutrition shakes to gut-bacteria fecal tests.

[Read: The harder, better, faster, stronger language of dieting]

What and when most people choose to eat is no one’s business but their own, but someone like Dorsey isn’t most people: He leads a platform with hundreds of millions of active users, built for the quick, contextless dissemination of ideas. As biohacking’s most powerful disciples become more committed and more evangelical, what does that portend for the vast workforces they employ, and for the far larger populations whose lives are affected by their products and policies?

Intermittent fasting, like most health-and-wellness behaviors, can exist anywhere on a spectrum that runs from very dangerous to potentially beneficial, depending on who’s doing it and how it’s implemented. Fasting in one form or another has been a part of human eating behavior for millennia, and although scientific research on it is still preliminary, early studies suggest it might help reduce the risk of heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. For people with eating issues, though, fasting can be a very risky trigger for anorexia or bulimia. For most people, exploring Dorsey’s lengthy, everyday fasts without oversight from a doctor or nutritionist is probably unwise. (Dorsey and Twitter did not immediately respond to requests for comment.)

On his Twitter account, Dorsey doesn’t mention anything about long-term disease risk or even weight loss, which is a purported benefit of fasting that’s gained the practice a lot of attention over the past several years, including from celebrities such as Kourtney Kardashian and Chris Pratt. Instead, Dorsey focuses on how much time slows down when he hasn’t eaten anything. Considering the demands of his job, it’s not surprising that a longer day would be important to him: Silicon Valley is, by and large, always looking to find a way to do a little bit more work. The tech industry also employs a younger-than-average workforce, full of burned-out Millennials who are expected to performatively hustle in order to curry professional favor and advance their career, creating what’s potentially an ideal environment for unhealthy “health” practices to proliferate.

Whether any Silicon Valley tech companies have implemented biohacking behaviors as an expectation for their employees is hard to know, but the industry itself produces a lot of diet programs and products, and it has a history of coercive eating policies for its workforce. Many big tech companies have on-site employee cafeterias that provide food for free or reduced cost. “By helping your employees make healthier decisions, your business benefits with reduced absenteeism and more productive energy,” wrote Andrea Loubier, the CEO of Mailbird, in a 2017 op-ed that encouraged other tech execs to follow Google’s lead and provide employees with certain types of food in-house, as well as with calorie-counting information. These policies are usually framed as a win-win for employers and their workforce—who doesn’t want a free lunch?—but in the end, they still tend to keep employees close to their desk and working as much as possible.

[Read: The myth of the cool office]

For companies that can’t build on-site food service for their employees, it’s possible to take a strong-arm approach to moderating their workforce’s diet and physical activity in other ways. Office wellness programs are popular and widespread even outside of the tech sector, with many of them featuring things such as office weight-loss challenges that encourage employees to restrict their eating for fun and prizes. As the journalist Angela Lashbrook argues, these programs can act as employer surveillance masquerading as health. “It’s perfectly legal to increase health-care premiums based on the failure of a customer or their partner to achieve certain benchmarks in an insurance-affiliated wellness program,” she writes.

In collecting detailed data about weight or physical activity, workplace wellness takes another step toward punishing failures that don’t necessarily show up in the quality of a person’s work, helping make an ever larger portion of a person’s existence fodder for performance reviews.

Certainly, it’s possible for executives to keep their personal-health practices separate from what they expect of others. But tech as a business sector has long been notorious for its bad boundaries between the personal and the professional. Silicon Valley can give the impression that all personal choices should be made for the end goal of doing ever more work and generating ever more money for founders or venture capitalists, which is part of why so many people find it unnerving to watch a man with so many employees decide that not eating is a valuable practice. If everyone above you on the organizational chart refuses to eat in order to squeeze a little more work out of an already long day, consuming your sad desk salad might be a little higher-stakes than you thought. The person who signs your paychecks might be watching.

Many conservative Christian denominations have spent the past several years reckoning with their legacy of white supremacy. The darkest parts of American history are full of Christian characters, including scores of pastors and theologians. A number of still-existing denominations, among them the Southern Baptist Convention and the Presbyterian Church in America, were first formed to defend slavery. Some well-respected Christian scholars dedicated their lives to rationalizing racial hierarchies with the Bible. And terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan claimed an explicitly Protestant identity, with some pastors openly supporting their cause.

To reconcile this past, contemporary pastors have gathered at annual conventions to pass numerous resolutions opposing racism, albeit with occasional stumbles. A flagship Southern Baptist seminary published a report in late 2018 detailing its own long history of support for slavery and Jim Crow policies. “We knew, and we could not fail to know, that slavery and deep racism were in the story,” wrote R. Albert Mohler Jr., the seminary’s president. “We comforted ourselves that we could know this, but since these events were so far behind us, we could move on without awkward and embarrassing investigations and conversations.” The denomination’s first apology for its slavery-promoting past came in 1995.

Repenting for the sins of forefathers is much easier than recognizing the racism embedded in religious institutions and cultures today, however. In The Color of Compromise, the writer Jemar Tisby challenges the notion that white supremacy is merely a legacy, and not a present reality, in the church. “Christian complicity with racism in the 21st century looks different than complicity with racism in the past,” he argues. “It looks like Christians responding to black lives matter with the phrase all lives matter. It looks like Christians consistently supporting a president whose racism has been on display for decades.” Perhaps, he writes, “Christian complicity in racism has not changed much after all.” While Tisby is nominally writing for the church at large, he is specifically focused on its conservatives—“Bible-believing” Christians who come out of traditional theological backgrounds similar to his own.

(Zondervan)

(Zondervan)A broad range of conservative Christian leaders, such as Mohler, apparently yearn to repent for their racist inheritance. Their failures—in the eyes of Tisby, who is part of an emerging generation of activists in the church—illustrate how people who think in Bible verses and call one another “brother” and “sister” sometimes misunderstand the issue of racism. This book is partly an attempt to clarify what racism actually means. But ultimately, the writer’s goal is larger. Tisby calls on his fellow Christians to take full responsibility for their complicity in white supremacy, and to commit to changing America.

While Tisby’s take on this topic is not exactly new, it is timely: The racial divide within American Christianity has been exacerbated under Donald Trump. According to the Public Religion Research Institute, white evangelical Protestants have consistently favored the president since he was elected, with roughly 72 percent of them expressing support in the fall of 2018.

By contrast, three-quarters of black Protestants said they viewed him unfavorably in the same poll. Black Christians expressed despair when the president was elected, both because of his racist rhetoric and past and because they felt ignored and even antagonized by their white peers. Evidence suggests that some have left majority-white churches. And yet, prominent white Christian leaders have celebrated Trump’s presidency: One Texas church, First Baptist Church of Dallas, composed and premiered an original “Make America Great Again” hymn in the summer of 2017.

Tisby has spent years working to start conversations among white Christians about racism. He runs a blog about the black Christian experience and hosts a podcast, Pass the Mic, on the same subject. His writing has been published widely in popular outlets, and he speaks frequently on racial reconciliation at churches and universities. More recently, however, Tisby has leaned on history to help him in his work against racism. After earning his seminary degree, he enrolled in a Ph.D. program in history at the University of Mississippi, focusing on race, religion, and social movements in the 20th century. In The Color of Compromise, he seems to see history primarily as a tool of persuasion and advocacy. “Paradoxically, although this is a book about the past,” he writes, “it is really about the future of the American church.”

Tisby’s historical frame is helpful in another way: It offers white conservative Christians language for talking about racism in a way they can accept and understand. Tisby invites these readers to walk with him through America’s past, crafting a narrative that feels safely apolitical and can be understood with scholarly remove. As Tisby gets closer to the present, however, he shows that the sins of the past may not be so different from those of today.

Instead of simply chronicling the horrors of racism, Tisby shows white Christians’ indifference toward it. In the lead-up to the Civil War, Tisby writes, the influential theologian James Henley Thornwell framed slavery as a “political” issue that fell beyond Christianity’s moral ambit. In Thornwell’s worldview, the church could “merely assert what the Bible teaches,” according to Tisby, and “must remain silent on that which the Bible is silent.”

This worldview shows up throughout The Color of Compassion. As the civil-rights movement began taking shape in the 1950s and ’60s, “people of faith may not have given their full support to the most extreme racists,” Tisby says, “but neither did they oppose racists outright or openly disagree with racist objectives.” Six decades later, closer to the present tense, Black Lives Matter activists protested police violence toward African Americans. “Many white Christians viewed the killings … as isolated events,” Tisby writes. “They could not understand why black people and other keen observers had such strong reactions.”

Because many traditions teach that salvation is personal and individualized, Tisby argues, some Christians often frame racism as a matter of individual sin rather than systemic bias. This can engender blindness or skepticism toward theories of structural racism, which help explain the vast gaps between white and black Americans in wealth, educational outcomes, and rates of incarceration. “Many white Christians wrongly assume that racism only includes overt acts, such as calling someone the ‘n-word’ or expressly excluding black people from groups or organizations,” Tisby writes. In his view, this is wildly insufficient: “Being complicit [in racism] only requires a muted response in the face of injustice or uncritical support of the status quo.”

Tisby calls on “Bible-believing Christians” to educate themselves about racism, develop interracial relationships, and commit to supporting activism against racism. He encourages churches to distribute reparations from their collections, to declare a “year of Jubilee” for black members, or to fund black-led church plants. Perhaps most challengingly, he calls for firm resolve on race-related issues that some consider strictly personal or politically inflammatory: Take down Confederate monuments. Don’t send kids to schools that have become segregated through zoning codes or high tuition. Oppose police violence toward people of color. And don’t support a president who has “obvious racist tendencies.”

As Tisby himself acknowledges, these recommendations might seem painfully obvious to some, especially his activist peers. But Tisby’s ideal readers may be the people who are ready to pick up a book about Christianity and racism and be challenged by what they read. Step-by-step instructions for reducing racism are useful only if they reach people who don’t already agree with Tisby’s ideas.

In the final anecdote included in the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary’s report, the authors detail a 1961 visit to the seminary by Martin Luther King Jr. Hundreds of students crowded into the campus chapel to hear him speak; a group of them later called on the city’s mayor to desegregate its restaurants. Members of white churches around the South were appalled. White southerners wrote letters to protest King’s appearance and voted to withhold funds from the institution. Eventually, the school’s president, Duke McCall, apologized for King’s visit.

The authors of the 2018 report describe McCall as a “moderate” who wanted to maintain the “honorable middle ground” on civil rights and segregation. This is where the seminary report ends—without extending the analysis to the current day. Then, as now, white Christians were willing to consider issues of racism, but wanted to do so with the comfortable backing of consensus. Then, as now, activists in the church were sidelined: Tisby writes that he and his peers are often called divisive, offensive, radical, misguided, and more.

Fifty-five years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, and 154 years after the end of slavery, it is true that racial dynamics are different in America, and within the American church. Still, the patterns of history, and the tug of moderation, remain the same. That’s where this book offers value: Tisby is the rare writer on race who could have impact in rooms where progressive consensus cannot be assumed.

After just experiencing the warmest December on record, much of Australia is still enduring a sweltering January, with many new high-temperature records being set. The brutal heat waves have resulted in health warnings being issued, telling residents to stay indoors and to take special notice of animals in their care. Overtaxed power grids have failed several times, leaving thousands without power; wildfires are burning in Tasmania; and wild animals are suffering as watering holes dry up. Last week, the town of Port Augusta set a new record high of 121 degrees Fahrenheit (49.5 degrees Celsius). Forecasts have the heat lasting at least through the end of January, possibly leading to yet another hottest-month record.

Melissa Herrington, artist

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain forever altered and scandalized the established art world, challenging the very definition of art. But what if the founding father of conceptual art was actually a woman? Recent speculation is that Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the forgotten pioneering feminist, may be responsible for the most significant work of art of the 20th century.

Cynthia Herrup, history and law professor, USC

For duration, extent of damage, and betrayal of trust, no scandal matches the Catholic Church’s exploitation of authority over sexuality.

Jenna Glass, author, The Women’s War

Larry Nassar’s sexual abuse of more than 300 young gymnasts is a crime, not a scandal. But the massive cover-up; the length of time it went on; and the number of adults who made excuses, ignored complaints, and chose to protect institutions instead of the gymnasts? That’s the biggest sports scandal ever.

Graham Roumieu

Graham RoumieuKitty Kelley, biographer

A scandal is a soul-destroying event that rains down shame and disgrace. The most recent moral repugnancy is the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi journalist who was dismembered in Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul last year.

Kristin Hahn, writer and producer, Dumplin’, and author, In Search of Grace

Drag queens being outlawed in the Old Testament (Deuteronomy)—because a good drag show does the Lord’s work by celebrating the feminine in all of us.

Reader ResponsesLeslie Ellen Brown, Spring Mills, Pa.

The bargain of 1877 between supporters of the Republican presidential candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, and Southern industrialists, restoring Southern power to the federal government.

Roger L. Albin, Ann Arbor, Mich.

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 was probably the first major financial crisis. It had everything: massive overvaluation of a questionable asset, dramatic collapse with deleterious systemic consequences, insider trading, bribery, and ineffectual subsequent regulation. We never learn.

Graham Roumieu

Graham RoumieuMaida Follini, Halifax, Nova Scotia

During and after his term as vice president, Aaron Burr conspired with the British to set up an independent country in the southwestern United States and parts of what is now Mexico. He was arrested for treason, but found not guilty.

Sanjiv Maheshwari, New Delhi, India

The Opium Wars, which Britain and France waged against China in the mid-19th century, with the aim of continuing to sell opium to the Chinese people. In the process, the imperial summer palace in Beijing was burned, and the Chinese ultimately ceded Hong Kong to Britain. The Chinese recall this period in their history as the “century of humiliation.”

Elinor Adams, Phoenix, Ariz.

The affair between Alexander Hamilton and Maria Reynolds created the first major sex scandal in the U.S., and completely destroyed Hamilton’s political career.

Richard Marcovitz, Toronto, Ontario

The Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish French army captain was wrongly convicted of espionage. He was partially exonerated after political and intellectual leaders convinced many of their countrymen that Dreyfus was innocent—and that members of the ethnic majority should not collude to blame a problem on a member of a minority group.

Harvey Karten, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Peter Minuit’s conning the Lenape tribe in 1626 to sell Manhattan Island for 60 guilders’ worth of trade goods, or no more than $15,000 in today’s dollars. The value of real estate across Manhattan today is more than $1 trillion.

Want to see your name on this page? Email bigquestion@theatlantic.com with your response to the question for our May issue: What is the greatest act of courage?

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah—Three weeks after the initial airing of Lifetime’s Surviving R. Kelly, the 2019 Sundance Film Festival saw the premieres of two separate documentaries that chronicle previously reported allegations of sexual abuse. The director Ursula Macfarlane’s Untouchable threads together numerous accounts of the film mogul Harvey Weinstein’s alleged systematized predation. Leaving Neverland, a two-part docuseries from the director Dan Reed, follows two men as they attempt to reconcile the effect that the late Michael Jackson’s alleged abuse has had on their lives. Though they vary in form and aesthetic sensibility, both new productions are jarring works that call attention to the wide-ranging effects of alleged sexual abuse and the silence that often follows it.

The men implicated in all three recent productions repeatedly denied allegations of abuse and, in some cases, intimidated alleged victims before they could speak out. But the #MeToo-era documentary is a fraught genre for reasons that extend beyond the ire of the accused (or in Jackson’s case, an estate). To captivate audiences and shift public perception, a documentary must offer new reportage, deep analysis, or a freshly cohesive vision of its subject. Moving viewers with stories of sexual assault—without veering into sensationalism or kitsch—is a delicate task. It requires thoughtful aesthetic pairing, compassionate interviewing, extensive research, and a thorough understanding of how systemic abuse can work. There are many ways to err.

Perhaps the most common, and most troubling, pitfall of the sexual-misconduct documentary is the extraordinary emotional excavation it demands of alleged victims. The director dream hampton’s Surviving R. Kelly, for example, is a powerful six-hour series characterized largely by gut-wrenching testimony from women who say that the singer abused them mentally, physically, and sexually. Many of them are visibly shaken as they speak. At times, such as when Asante McGee breaks down upon visiting the house where she alleges Kelly held her hostage, the footage can feel nearly impossible to stomach—particularly when contrasted with the more relaxed tone of others who appear in the documentary: the men who have supported Kelly throughout his career.

Macfarlane’s Untouchable relies on similarly strenuous labor from women who accuse Weinstein of assaulting them (and on the symbolism of having premiered at Sundance, where the actress Rose McGowan alleges Weinstein raped her in 1997). The women featured in the documentary recount stories that span decades, tearily indicting themselves in front of the camera for having been ensnared by Weinstein’s alleged traps. But where Surviving R. Kelly takes care to contextualize the onscreen accounts with expert testimony from psychologists and social scientists who explain foundational concepts such as grooming and social isolation, Untouchable doesn’t grant its sources that same narrative courtesy. It provides no clear reminder that these women were not foolish or negligent to have been around Weinstein, or that many serial abusers disarm their victims with power, charisma, or force. Without that kind of intra-textual framing from the filmmakers, the women’s testimonies are particularly vulnerable to misinterpretation by those viewers less familiar with the psychological and social ramifications of abuse.

Leaving Neverland, however, is a deeply empathetic work. Its two main subjects, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, now in their late 30s and early 40s, respectively, speak with candor and clarity throughout the four-hour documentary about meeting Jackson as children and being lured into his show-business orbit. They are remarkably self-possessed as they recount not just sexual abuse, but also the anguish of experiencing manipulation by a trusted figure. Both men repeat that Jackson was larger than life, that receiving attention from him made them feel unimaginably special. They allege that Jackson intentionally intermingled affection and abuse, referring to them as “best friend” or “little one” to keep them enamored of him even as he grew close to other boys. Their personal recounting is buttressed by archival footage, old photographs of the singer in their homes, and even copies of faxes he apparently sent to Robson, signed “apple head.”

Though Jackson’s alleged abuses have been reported since 1993, when he was first accused of child molestation, Leaving Neverland offers a striking new lens through which to see the late singer’s legacy: the effect it continues to have on those he allegedly groomed. The documentary is a thorough, brutal accounting of Robson’s and Safechuck’s psychological states both as children and as adults, attempting to name what they say happened to them. In that sense, it functions less as a work of journalism—or even a heated takedown of Jackson himself—and more as a thoughtful narrative rendering of the two alleged victims’ stories.