Recentemente, fiz um relato no Twitter sobre a importância da pedagogia crítica na formação de professores da Universidade de Oxford, e o tema despertou tanto o interesse de professores quanto raiva de haters, me chamando de mentirosa. Achei prudente, então, contar um pouco mais aqui da minha experiência.

É claro que uma grande parte do público mais engajado de Bolsonaro acha que o jornal norte-americano The New York Times ou as universidades de Oxford ou Harvard estão minadas pelo “marxismo cultural” – e ter Paulo Freire na formação de professores seria apenas a prova cabal disso. Só que ainda existe uma grande parte das elites brasileiras que, mesmo sendo bolsonarista e adepta ao projeto Escola Sem Partido, sonha que seus filhos estudem nas melhores universidades norte-americanas ou europeias. Ou seja, em universidades cuja a formação dos professores se dá em grande parte por meio da pedagogia crítica.

Infelizmente, ainda prevalece no Brasil uma profunda ignorância e uma obsessão quase fantasmagórica sobre a obra Paulo Freire – o suposto guru da doutrina satânica gayzista, feminista e marxista que reina em nosso sistema educacional. Quando era candidato à Presidência, Bolsonaro prometeu “entrar com um lança-chamas no MEC e tirar Paulo Freire lá de dentro”. Sobre tal doutrinação, no entanto, não há qualquer evidência empírica.

Paulo Freire é muito mais celebrado lá fora do que no próprio país de origem: ele é terceiro autor mais citado no mundo na área de ciências humanas, superando Karl Marx e Michel Foucault. O livro A Pedagogia do Oprimido (1968) tem 75 mil citações no Google Scholar e é a única obra brasileira que está entre as cem mais lidas nas disciplinas de países de língua inglesa.

Dito isso, é possível que cientistas sociais no Brasil – como eu – passem sua formação inteira sem serem confrontados como a obra de Paulo Freire. O mesmo dificilmente irá acontecer nos principais centros de excelência acadêmica no mundo. Ou seja, o problema da educação no Brasil, ao contrário da fantasia que assombra as mentes bolsonaristas, é justamente a falta de uma educação que incentive a autonomia e o pensamento crítico.

Os 12 anos do PT certamente fizeram muito pela educação brasileira, especialmente no que se refere ao acesso ao ensino superior. Mas ao contrário do que muitos acreditam, não houve (por falta de vontade ou de tempo) a tão necessária transformação da estrutura pedagógica do sistema educacional, capaz de fomentar o espírito democrático de sujeitos críticos. As eleições de 2018, aliás, comprovam isso.

Formação de professores na Universidade de OxfordQuando assinei meu contrato para trabalhar na Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento Internacional, o Oxford Learning Institute começou imediatamente a me contatar para que eu me inscrevesse no curso de um ano de formação de professores – o que era “altamente recomendado”.

Matriculei-me, então, no curso, cujo resultado final era a elaboração de um portfólio de ensino que, se aprovado, nos daria o título de membro vitalício (fellow) da Academia de Ensino Superior, cujo diploma certifica que você é um professor universitário que segue os principais padrões de excelência de ensino no Reino Unido.

Na minha turma estava toda uma leva de novos professores na área de humanidades e ciências sociais (as ciências exatas tinham uma turma separada, mas o programa era o mesmo).

Mas o que, exatamente, eles chamavam de excelência de ensino?

No primeiro dia de aula, o professor nos alertou: “Se vocês estão em busca de dicas de técnicas didáticas, aqui é o lugar errado. Cada professor tem seu estilo. Um bom professor é o que consegue ser claro e sabe refletir sobre o seu entorno e, ao mesmo tempo, é capaz de estimular a reflexão ao seu entorno”.

O curso tinha uma metodologia tão simples como profunda. Líamos textos diversos, mas fundamentalmente os de pedagogia crítica sobre a importância de os professores refletirem sobre as relações de poder em sala de aula. A principal obra do curso era o famoso livro de Stephen Brookfield, Becoming a critically reflective teacher, que tem influências de Paulo Freire e Antonio Gramsci.

O curso não doutrinou ninguém.Fazíamos debates profundos em pequenos grupos sobre o papel dos professores, exercícios autobiográficos críticos (quais relações de opressão e ou emancipação que tínhamos experimentado no passado e que estávamos reproduzindo como professores?), reflexão crítica de nossas avaliações por alunos. Observamos e fomos observados em sala de aula por nossos pares (o que é muito desafiador!) e, por fim, formulamos nossos valores enquanto professores.

O curso não doutrinou ninguém. Eu era uma das únicas pessoas de esquerda na turma. Meus colegas liberais, de centro ou de direita, continuaram liberais, de centro e de direita. Mas todos nós entendemos e discutimos com seriedade as formas de opressão que existem em uma sala de aula, bem como sobre nossa atuação e clareza em sala de aula.

Observei a aula de meu colega liberal, que era professor do curso de Políticas Públicas. Ele também assistiu minhas aulas e me ajudou a ser mais clara em minha comunicação (eu tendo a ter um pensamento circular que pode prejudicar a atenção de alunos, especialmente em língua estrangeira). Foi ele que me alertou para o fato de que eu deixava que a discussão fosse dominada pelos dois únicos homens na sala de aula, em contraposição a 16 alunas mulheres.

Eu também aproveitei o método crítico reflexivo para refazer meus questionários de avaliação, possibilitando e encorajando meus estudantes a serem mais críticos. Descobri, por meio das avaliações dos alunos, que eu poderia ser mais direta nas minhas aulas, o que confirmava a observação de meu colega. Na avaliação seguinte (monitorada pelos meus pares e pelos tutores do curso), os estudantes apontaram que havia tido um salto qualitativo na qualidade de minhas aulas.

Todo o grupo de novos professores refletiu criticamente sobre sua própria postura em sala de aula, seja como técnica didática, seja como relação de poder. Após um ano de encontros do curso, nos foi colocada a seguinte pergunta: “qual o papel do professor?”

Apenas uma parte da turma escolheu “mudar o mundo”, e a outra metade disse que era fornecer instrumentos técnicos para os estudantes resolverem problemas. Estava tudo bem. Não havia uma resposta correta: o correta era o próprio diálogo entre os pares.

O curso também ajudou a desconstruir o mito da genialidade, de que existiriam alunos “fracos” e “fodas”.Eu, particularmente, aprendi a me colocar como professora mulher, jovem e latina e a detectar e desarmar o machismo implícito e inconsciente de alunos.

Não sei se eu me tornei uma professora melhor desde então. Mas espero que sim. Aprendi a dar mais atenção ao estudante quieto, às mulheres e minorias em sala de aula. Aprendi a me colocar em uma posição de quem erra em sala de aula, mas está aberta mudar e ouvir críticas. Aprendi a falar menos e ouvir mais e, principalmente, desenvolvi minhas habilidades de ensinar via métodos dialógicos de conversa e debates.

O curso também me ajudou a desconstruir o mito da genialidade, de que existiriam alunos “fracos” e “fodas” (e isso até gerou meu texto mais lido até hoje, O Precisamos Falar sobre Vaidade na Vida Acadêmica). Com o método da pedagogia crítica e da “autocrítica reflexiva” eu apenas me tornei mais sensível a minha própria postura e ao meu entorno.

A única coisa que eu, infelizmente, não aprendi a fazer neste um ano de curso foi revolução. Também não foi me dado o super poder da doutrinação. Qualquer pessoa que encara uma sala de aula sabe que esse não é um dom que temos: nossa realidade é muito mais burocrática do que deveria ser. Se tivéssemos o dom de mudar as pessoas, é bem provável que teríamos um outro cenário político – e não este afundado na mediocridade, nas notícias falsas e no obscurantismo.

The post Oxford e Harvard amam Paulo Freire, o pedagogo que Bolsonaro quer tirar do MEC com um lança-chamas appeared first on The Intercept.

“Hoje é no amor!” A cena do miliciano Major Rocha felizão em um churrasco, em que ele comemora com tiros para o alto os quatro anos do centro comunitário em “Rio das Rochas”, no filme Tropa de Elite 2, é um bom retrato da realidade das milícias no Rio de Janeiro. “É tudo nosso!”, ele grita. Mas um dia a casa cai. E foi o que aconteceu hoje, quando o Ministério Público e a Polícia Civil anunciaram a prisão de cinco milicianos acusados de grilagem de terras na zona oeste do Rio de Janeiro. Não era a intenção – mas, por tabela, a operação, batizada de Intocáveis, também esbarrou em dois suspeitos da execução de Marielle Franco e Anderson Gomes.

Um deles, preso na operação, é o major da PM Ronald Paulo Alves Pereira. Segundo a polícia, ele é grileiro nos bairros de Vargem Grande e Vargem Pequena e chefe da milícia de Muzema, no bairro do Itanhangá – de onde o carro usado no assassinato de Marielle partiu. O outro é Adriano Magalhães da Nóbrega, chefe da milícia de Rio das Pedras e ex-policial do Batalhão de Operações Especiais, o Bope, que está foragido. Expulso da PM por envolvimento com um dos principais clãs da máfia do jogo do bicho no Rio, o ex-capitão investiu na carreira de mercenário, trabalhando para bicheiros, políticos e para quem mais pagasse bem.

O envolvimento do ex-caveira com o assassinato da vereadora e seu motorista foi revelado pelo Intercept na semana passada. Ao menos seis testemunhas citam o policial como o assassino. A escolha da arma, o uso de munição de uso restrito e a competência técnica na execução do crime apontaram para o Bope ainda em maio de 2018.

Diga-me com quem andas e eu te direi quem ésDevido ao ótimo “perfil técnico”, em 2005 Adriano Magalhães da Nóbrega recebeu a medalha Tiradentes, a mais alta honraria do Legislativo fluminense, por indicação do então deputado estadual, hoje senador eleito, Flávio Bolsonaro, do PSL, o filho 02 de Jair Bolsonaro. O ex-caveira também recebeu outras duas honrarias, de louvor e congratulações por serviços prestados à corporação, por atuar “direta e indiretamente em ações promotoras de segurança e tranquilidade para a sociedade”.

Flávio Bolsonaro também condecorou o major da PM Ronald Paulo Alves Pereira, que recebeu moção honrosa quando já era investigado como um dos autores de uma chacina de cinco jovens na antiga boate Via Show, em 2003, na Baixada Fluminense.

Quando estourou o escândalo do Coaf, Queiroz – velho amigo da família Bolsonaro – se escondeu em Rio das Pedras, reduto miliciano.Os dois são suspeitos de integrar o “Escritório do Crime”, um grupo de extermínio apontado como responsável pelo assassinato da vereadora Marielle Franco. Quatro PMs ligados ao grupo já foram presos. Pereira será julgado em 10 de abril deste ano. O grupo é acusado ainda de extorsão de moradores e comerciantes, agiotagem e pagamento de propina.

Segundo o MP, o grupo de milicianos presos na operação Intocáveis agia na região das comunidades de Rio das Pedras, na Zona Oeste do Rio de Janeiro. Foi justamente para lá que Fabrício Queiroz, o ex-PM e ex-assessor do senador eleito do PSL Flávio Bolsonaro foi se esconder depois que estourou o escândalo sobre sua movimentação financeira suspeita.

O Coaf detectou uma movimentação de R$ 7 milhões, incompatível com a renda do ex-assessor. O dinheiro era depositado por outros assessores de Flávio Bolsonaro e de seu pai, Jair Bolsonaro. A primeira-dama Michelle Bolsonaro chegou a receber um cheque de R$ 24 mil de Queiroz. Já Flávio Bolsonaro recebeu 48 depósitos suspeitos no valor de R$ 2 mil cada.

Família, a sagrada base de tudoA preocupação de Flávio Bolsonaro com a família é tocante. Além de arranjar emprego para a esposa e filhas de Fabrício Queiroz – uma delas como assessora fantasma de seu pai –, ele empregou também a mãe e a esposa do ex-Bope Adriano Nóbrega. Sim, o mesmo que é apontado como um dos assassinos de Marielle Franco.

A mãe do ex-policial, Raimunda Veras Magalhães, também é sócia de um restaurante que fica longe da Assembléia Legislativa do Rio de Janeiro, mas em frente à do Banco Itaú onde foram feitos 17 depósitos em dinheiro vivo na conta de Queiroz. Ela é citada nas movimentações suspeitas detectadas pelo Coaf.

Flávio Bolsonaro segue a cartilha de dizer que “não sabia de nada”. Nem do que faziam seus próprios funcionários.Assim como “certos petistas”, Flávio Bolsonaro disse em nota que não sabia de nada e que, devido às últimas notícias, se sente perseguido. “Quanto ao parentesco constatado da funcionária, que é mãe de um foragido, já condenado pela Justiça, reafirmo que é mais uma ilação irresponsável daqueles que pretendem me difamar”. O senador eleito jogou no colo do ex-assessor Queiroz a responsabilidade pelas indicações de seus assessores. Seu ex-funcionário aceitou de bom grado, enviando até uma nota à imprensa esclarecendo que, de fato, conhecida o ex-caveira Adriano e foi o responsável por indicar suas parentes para trabalhar para Bolsonaro.

Flávio ostenta no próprio Instagram sua foto com o pai, Jair Bolsonaro, e com os PMs Alan e Alex, presos na operação Quarto Elemento.

Divulgação.

É possível que Flávio Bolsonaro também não soubesse a ficha técnica de outros dois policiais que participaram de sua campanha e foram presos na Operação Quarto Elemento, também desencadeada pelo Ministério Público, que investigava uma quadrilha de policiais especializada em extorsões. Pode ser que ele também não soubesse que, de acordo com o MP, a milícia de São Gonçalo organizou um ato de campanha em favor do Coronel Salema, seu colega de partido, eleito deputado estadual com quase 100 mil votos.

Ah, essa última é difícil de negar: além dos dois terem feito campanha juntos, Flávio Bolsonaro chegou a anunciar: “mais um guerreiro ao nosso lado!”. Parece que agora está ficando claro a qual lado ele estava se referindo.

O MecanismoOrgulhosa de ser militarista, a dinastia Bolsonaro nunca escondeu seu apreço pela milícia, grupos de paramilitares formados por ex-policiais, PMs, bombeiros e agentes penitenciários que torturam, roubam, traficam e dominam economicamente, grande parte do Rio de Janeiro.

Flávio Bolsonaro já propôs inclusive a legalização desses grupos paramilitares. No início de seu segundo mandato na Assembléia Legislativa do Rio, em 2007, ele votou contra a instalação da CPI das milícias, que entrou em pauta após um grupo de milicianos torturar por horas a fio uma equipe de jornalistas do jornal O Dia. A justificativa? Milícias não eram tão ruins assim e as pessoas são muito felizes em áreas dominadas por paramilitares.

“Sempre que ouço relatos de pessoas que residem nessas comunidades, supostamente dominadas por milicianos, não raro é constatada a felicidade dessas pessoas que antes tinham que se submeter à escravidão, a uma imposição hedionda por parte dos traficantes e que agora pelo menos dispõem dessa garantia, desse direito constitucional, que é a segurança pública”, disse à época, na Alerj.

Em casa a banda toca nesse ritmo. Em 27 anos de discursos como deputado na Câmara, o pai Jair Bolsonaro defendeu milicianos “do bem” e grupos de extermínio pelo menos quatro vezes. A primeira, em 2003, ao defender grupos de extermínio:

“Enquanto o Estado não tiver coragem de adotar a pena de morte, o crime de extermínio, no meu entender, será muito bem-vindo. Se não houver espaço para ele na Bahia, pode ir para o Rio de Janeiro. Se depender de mim, terão todo o meu apoio, porque no meu Estado só as pessoas inocentes são dizimadas.”

Em 2008, ao criticar o relatório final da CPI das Milícias, Bolsonaro disse que “não se pode generalizar” ao falar de milicianos. Na época, a CPI pediu o indiciamento de 266 pessoas, entre elas sete políticos, suspeitas de ligação com grupos paramilitares no Rio.

“Querem atacar o miliciano, que passou a ser o símbolo da maldade e pior do que os traficantes. Existe miliciano que não tem nada a ver com ‘gatonet’, com venda de gás. Como ele ganha 850 reais por mês, que é quanto ganha um soldado da PM ou do bombeiro, e tem a sua própria arma, ele organiza a segurança na sua comunidade. Nada a ver com milícia ou exploração de ‘gatonet’, venda de gás ou transporte alternativo. Então, Sr. Presidente, não podemos generalizar.”

Quando foi relembrado sobre este apreço pelas milícias durante a campanha eleitoral de 2018, Bolsonaro fez a egípcia e se disse desinteressado no tema. “Hoje em dia ninguém apoia milícia mais não. Mas não me interessa mais discutir isso”, disse.

Jair Bolsonaro, vale lembrar, foi o único presidenciável a não se manifestar sobre a execução de Marielle Franco e Anderson Gomes. E Flávio Bolsonaro foi o único deputado que votou contra a vereadora assassinada receber a medalha Tiradentes como uma homenagem póstuma.

No fim das contas, o brasileiro parece ter eleito o Major Rocha achando que estava votando no Coronel Nascimento. Talvez seus eleitores precisem assistir à Tropa de Elite de novo.

Correção: 22 de janeiro de 2018, às 20h46

Este texto inicialmente afirmou que a mãe e a esposa do ex-PM Adriano Nóbrega fizeram depósitos na conta do Fabrício Queiroz. Na verdade, foi apenas Raimunda, a mãe do ex-policial. O texto foi atualizado para refletir a mudança.

The post As ligações dos Bolsonaro com as milícias appeared first on The Intercept.

President Donald Trump’s new offer to open the federal government in exchange for funding for his wall on the southern U.S. border includes a major change to immigration policy that was not included as part of his public announcement.

The Trump administration had claimed that it would support legislation known as the BRIDGE Act — which includes protections for Dreamers — in exchange for concessions by Democrats. Upon closer investigation, that turned out to be a lie.

Trump’s offer to Democrats, revealed Monday night, actually gives him even more of what he has wanted in immigration policy, which is an end to the legal process that allows people to present themselves at a U.S. port of entry and apply for asylum. Trump’s new policy would ban such asylum-seeking for Central American minors and require those fleeing violence or persecution to apply in their own country instead.

The Trump administration, however, has also made that process effectively impossible. The appropriations bill that’s currently on the negotiating table creates the “Central American Minors Protection Act,” which would allow minors from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras with a “qualified parent or guardian” in the United States to apply for asylum in their home countries. (The bill does not define “qualified” parent, and it’s unclear whether the program would be limited to the children of U.S. citizens and permanent residents.) But far from treating would-be asylum-seekers’ claims with urgency, the bill gives 240 days (about eight months) for the establishment of eight processing centers that would deal with these claims — even though the ban on requesting asylum at the border would go into effect immediately.

“There is no way to square the way the administration has described this plan with what it actually is.”“There is no way to square the way the administration has described this plan with what it actually is,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a policy analyst at the American Immigration Council, describing the proposal as a “de facto asylum ban” for the vast majority of cases. Central American minors who don’t have a qualified parent would no longer have a route to asylum, though they could ostensibly come to the border and request lesser protections with no route to citizenship, like withholding of removal or protections under the Convention Against Torture, Reichlin-Melnick noted.

The bill also caps the number of applications that can be processed at 50,000 per year, and says no more than 15,000 people can be granted asylum under the program annually. The Department of Homeland Security’s decision would not be subject to judicial review. If the legislation is passed, people who are eligible for the program will could be sent back to their home countries — without regard for their fear of persecution — if they trek to the U.S. and ask for asylum here.

The notion that asylum-seekers should apply back in their own countries is often presented with a veneer of humanitarian concern. Trump said in a speech on Saturday that the “heartbreaking realities that are hurting innocent, precious human beings every single day on both sides of the border” must end.

Indeed, even former President Barack Obama agreed to some extent that applying to emigrate while in one’s home country was better than asking for asylum at the U.S. border. And so, in 2014, as thousands of unaccompanied Central American minors were showing up at the U.S.-Mexico border, the Obama administration created the little-known Central American Minors program to encourage people to do just that.

CAM allowed children who were fleeing violence in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras — and who had family members legally in the United States — to be considered for refugee resettlement while they were still in their home countries. Those who didn’t meet the eligibility criteria for refugee admission could be granted humanitarian parole, a temporary designation that would allow them to spend two years in the United States. (Notably, the Obama-era program was a supplement to existing asylum protections. Unlike the current GOP proposal, it didn’t impact the process of requesting asylum at the border.)

CAM was created for the children of people like Carmen Polanco, who is in the United States under Temporary Protected Status and has not seen her 13-year-old son since she fled El Salvador in 2011. Shortly after she left, her son witnessed a gruesome gang murder, a traumatizing experience that’s been followed by years of intimidation and bullying by local gangs, said Polanco, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to protect her family. In 2015, she applied to be reunited with her son under CAM. His refugee application was rejected, but in late 2016, Polanco’s son was conditionally approved for parole, and he was set to undergo a medical examination in early 2017.

Then Trump entered office, and Polanco’s son’s exam was inexplicably canceled. The government’s website continued to broadcast word of the program, yet applicants at various stages throughout the process began to notice that their applications were not moving. In August of that year, DHS finally announced that it was canceling the program. DHS also rescinded parole for about 2,700 people who, like Polanco’s son, had been conditionally approved for parole but had not yet traveled to the United States.

We now know, thanks to a lawsuit filed by the International Refugee Assistance Project, that the Trump administration shut down the CAM program — canceling interviews and blocking travel to the United States — in January 2017, without notifying the public.

“The sudden, unexplained shutdown of the CAM parole program, which was carried out in secret immediately after President Trump’s inauguration, can only be explained by the president’s animus toward Latinos and Central Americans,” said Linda Evarts, an attorney at IRAP.

Last month, U.S. Magistrate Judge Laurel Beeler found that the administration’s mass rescission of conditional approvals of parole was illegal under the Administrative Procedure Act, which deals with the way federal administrative agencies propose and establish regulations. Beeler’s decision was narrow, but it represents yet another instance of the courts rejecting rash policy changes by the Trump administration that have the intended, if unspoken, effect of keeping Latin American migrants out of the United States, regardless of how they try to get here.

IRAP brought the lawsuit on behalf of 12 applicants and beneficiaries of the CAM program, charging that the abrupt termination of the program moving forward was also illegal under the APA, and that the Trump administration’s actions were unconstitutional. Beeler rejected those claims, and she has not yet ruled on IRAP’s motion for a preliminary injunction that would force the Trump administration to reverse its rescission.

Still, Evarts described Beeler’s ruling as “a very important first step,” because the judge’s finding that the government violated the APA could set the stage for how she will rule on the preliminary injunction.

“The proposed legislation…would create a second-class asylum system for Central American children that is irrational and cruel.”The Trump administration’s new proposal for Central American minors does nothing for those impacted by the 2017 rescission of conditional parole, Evarts said. “The proposed legislation would eviscerate the humanitarian protection system for asylum seekers that has enjoyed bipartisan support for decades. It would create a second-class asylum system for Central American children that is irrational and cruel, requiring them to apply from their home countries or be denied asylum.”

Wendy Mejia, 16, hugs her aunt after her arrival from El Salvador at Baltimore-Washington International Airport on Nov. 12, 2015. After 15 years apart, Wendy and her brother Brian reunited with their parents, becoming among the first teenagers to be granted refugee status and permission to travel legally to the United States through the State Department’s Central American Minor program.

Photo: Patrick Semansky/AP

By creating the CAM program, the Obama administration acknowledged that the threat posed by gangs and state security forces in the Northern Triangle countries could amount to persecution or a fear of persecution, one of the elements of a refugee claim. Typically, refugee resettlement is an option only available to individuals who’ve already fled their home countries, but the U.S. government wanted to discourage minors from making the perilous journey through Central America.

Within the first week of Trump’s presidency, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which is housed in DHS, canceled more than 2,000 CAM interviews that were scheduled in the first three months of 2017, according to court documents. The government also stopped issuing decisions to people who’d been interviewed under the program, stopped scheduling medical exams for people who had been conditionally approved for parole, and blocked travel for people who had cleared their medical exams. As all this was happening, “at least five webpages controlled by USCIS, the State Department, and the U.S. embassies in El Salvador and Honduras represented that the CAM program continued to be in operation,” Beeler wrote in her order.

The program was initially halted in anticipation of Trump’s January 27, 2017, executive order that is best known for containing the first iteration of the travel ban. Then-Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly issued a memo about implementing the executive order, in which he stressed that parole should be granted only “sparingly.”

In August 2017, the government said publicly for the first time that it had terminated the program and rescinded conditional offers of parole to 2,700 Central American minors. Those individuals were later told that they had 90 days to file a request for review of the denial of refugee status, in which they could present evidence that the officer who rejected their applications made a significant error, or that there are new facts that warrant a reconsideration of the officer’s decision. (There is no appeal process for such rejections, and it’s entirely within USCIS’s discretion whether to grant a review of an application.) “Many of those who filed [requests for review] in 2017 or early 2018 have not yet received decisions” on those requests, Beeler wrote.

Polanco filed a request for review in her son’s case in December 2017, and she has not yet heard back from USCIS, she said. She’s so desperate to be reunited with him that she’s “even thought about leaving and going there and bringing him back with me, walking,” Polanco said, speaking through an interpreter. Her son left Polanco’s parent’s home and is now living with her sister, due to his fear of gang activity in his family’s neighborhood. “He cannot go to church anymore. He cannot go to the stores. He cannot get out of the house,” Polanco said.

In a December 2016 report, outgoing USCIS Ombudsman Maria Odom called CAM “one of the most important programs DHS has developed in the last four years,” though she cautioned that it formed just “one piece of a comprehensive regional response needed to address the Northern Triangle refugee crisis.”

The program, as important as it was, was also flawed. Odom identified eight issues of concern in her report, including lengthy processing times, narrow eligibility criteria, and high costs. Another shortcoming of the program identified by advocates, as The Intercept previously reported, is that already fearful Central Americans put themselves at risk merely by applying for protections under the program — by repeatedly traveling to capital cities for interviews, people risked being tracked and hunted down by gangs.

A 2016 report prepared by the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee and grassroots groups in Central America and the United States found that “few minors (according to our survey, 2.5%) who take the traditional migration route through Mexico to seek asylum in the United States are aware of the CAM program. And even fewer (according to our survey, 1%) feel CAM is a legitimate alternative for them. Most could not wait a year to flee or did not fit the eligibility criteria.”

The report authors recommended an expansion of the program. Instead, Trump got rid of it.

During its short run, CAM provided a “lifeline” for many families, said Katie Shepherd, national advocacy counsel at the American Immigration Council. “It certainly wasn’t a perfect solution to a very systemic and difficult problem — that problem being pervasive gangs, domestic violence, and regional instability — but it did provide some avenue to some small portion of people, right? So it wasn’t a solution to the problem, but it did remedy the problem in some regards.”

The post Trump’s Shutdown Offer Creates a De Facto Asylum Ban for Central American Minors appeared first on The Intercept.

ISTANBUL—Pelin Ünker thought she had the scoop of a lifetime when Cumhuriyet, one of Turkey’s oldest newspapers, published her bombshell report that the family of Binali Yıldırım, then the country’s prime minister, owned vast offshore holdings. Yıldırım promptly admitted that the revelations were true—though he denied wrongdoing—and even invited an investigation into his two sons, who were named in the 2017 report.

That inquiry never materialized, and the authorities instead pursued Ünker, making her the first journalist in the world to be prosecuted for covering the Paradise Papers, a trove of some 13 million leaked documents that divulged tax loopholes used by the rich and powerful. A couple weeks ago, she was sentenced to more than 13 months in prison and fined $1,600 for insulting and defaming Yıldırım.

Ünker’s case exposes the perils of reporting in Turkey, where a sweeping crackdown has blunted civil society and turned the country into the world’s biggest jailer of journalists. Scores of media outlets that ran afoul of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government have been banned or forced to find new, more compliant owners. And even as Erdoğan grabs global headlines for denouncing Saudi Arabia over the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist killed in the kingdom’s Istanbul consulate in October, journalists in his own country labor under the threat of censorship, dismissal, or arrest.

[Read: The irony of Turkey’s crusade for a missing journalist]

Ünker was part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a global network that spent months sifting through the mass leak from a Bermuda law firm to lay bare the shadowy workings of the offshore financial industry. In her reporting, she found that Yıldırım’s sons had established shipping companies in Malta, which has a far lower corporate tax rate than Turkey, and had won a government contract back home. She also discovered that Serhat Albayrak—whose brother, Berat, is married to Erdoğan’s daughter—concealed offshore companies linked to the Turkish conglomerate the two Albayraks ran.

“My stories contained no slander, because the claims are not disputed, and not a single word of insult,” Ünker, 34, told me in a telephone interview after the verdict. “This sentence isn’t just about me. It’s punishing the act of journalism to intimidate others who might report this kind of news.”

Ünker can still count herself lucky. Should the appeals court uphold the verdict, Ünker is unlikely to serve more than a few days in jail, benefiting from a good behavior credit, her lawyer said. The judge ruled out a reprieve that would have eventually expunged her record, however, citing her propensity to commit the same “crime” again, Ünker and her lawyer said. Next time, she could wind up behind bars.

At least 68 of her peers, or more than a quarter of journalists jailed worldwide, are languishing in Turkish prisons, the Committee to Protect Journalists said last month. Other groups say that the figure is far higher; Human Rights Watch counts more than 175 journalists and media workers. The Turkish government says that it locks up those journalists who moonlight as terrorists or criminals. “It would never occur to us to discriminate by profession in these cases,” Erdoğan said last month. And to be sure, he has put away tens of thousands of people, including rights activists, politicians, and civil servants, most of them in a clampdown following a 2016 coup attempt against him. With a muzzled media and a cowed opposition, his drive to consolidate power has been largely unfettered. In June, Erdoğan—who first came to power in 2003—won election to a new supercharged presidency that puts most organs of the state under his control.

[Read: How did things get so bad for Turkey’s journalists?]

Almost 90 percent of Turkey’s news channels and papers are run by the government or businessmen close to it, according to Reporters Without Borders, which ranks Turkey 157th out of 180 nations in its World Press Freedom Index. Opposition voices have retreated to the web, but the long arm of the state extends there, too.

Necla Demir, the 29-year-old publisher of Gazete Karınca, faces up to 13 years in prison after prosecutors in Istanbul this month charged her with creating “terrorist propaganda” for the website’s coverage of a Turkish military offensive against Syrian Kurdish rebels in 2018. The indictment comes as Erdoğan threatens another incursion against the Kurdish militia, which has fought the Islamic State alongside U.S. soldiers, after President Donald Trump said that he’s withdrawing from Syria.

Turkey’s press has always worked within constraints, but enjoyed a brief heyday a decade ago, when Erdoğan needed its support to fight off the country’s secular old guard and champion a quixotic European Union membership bid.

Today, a trickle of mass-circulation newspapers still questions his authoritarian style of rule, but most outlets subscribe to an ardently nationalist view, giving short shrift to taboo topics such as Turkey’s conflict with the Kurds or human-rights abuses.

“There’s a suffocating climate of fear,” says Ahmet Şık, who spent 15 months in detention during his trial on terrorism charges, along with a dozen staff members from Cumhuriyet. “Cases are brought to stifle the handful of outlets writing critically of the administration, and the courts operate on government orders.”

Şık was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison in April for his coverage of alleged coup plotters and militant groups, but he remains free pending his appeal. A few months after his release, he quit journalism to run for parliament and won a seat with a left-wing opposition party. Nearly 30 of his colleagues at Cumhuriyet were sacked or resigned in September after a legal battle over management at the paper culminated in the appointment of a new chairman who had testified in court against Şık and his co-defendants.

Under its previous editors, Cumhuriyet was the sole Turkish outlet to collaborate on the Paradise Papers. When Ünker began working on the project, she would rush to the office in the middle of the night when a new batch of documents arrived, unable to contain her curiosity until morning. In the weeks after her son was born, she brought him to the newsroom so she could work on the story.

The disclosures about how global elites used offshore assets to reduce their tax burden led to a smattering of resignations around the world and calls for reform, at least outside of Turkey. Here, access to Ünker’s stories in Cumhuriyet’s online archives are blocked because of a court order.

“If our government officials and their relatives are hiding their wealth, the public ought to know,” Ünker said. “I never thought anyone would resign over this, but I did think the law, which calls for the disclosure and taxation of offshore accounts, would be applied—that just as regular citizens pay their taxes, the same would be expected of the rich.”

Her report had the opposite effect. When Yıldırım acknowledged that the companies existed and faced no repercussions, he normalized the practice. He became speaker of parliament after his post of prime minister was abolished, and is now running for mayor of Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city. Erdoğan named his son-in-law Berat Albayrak economy czar last year.

Ünker, meanwhile, quit Cumhuriyet after a decade at the paper to protest the new management. She now works as a freelance reporter for a German news organization, and is due back in court next month on defamation charges, this time against the Albayrak brothers. Another prison sentence looms.

City and teachers’ union officials in Los Angeles appear to have reached a tentative agreement to end a week-long strike, but the L.A. strike is just the latest flashpoint in an unprecedented wave of recent teacher activism. Over the past year, at least 409,000 educators have staged walkouts, nearly four times the number who did so in the major spate of strikes a half-century ago. What makes these recent strikes so stunning is that they come amid a decades-long slump in the influence of, and public support for, unions and labor activism.

The Academy Awards released its shortlist of 2019 Oscar nominees, in a year with no clear Best Picture front-runner. The 10 nominations for Roma are significant for the “firsts” that they mark: the film is the first produced by Netflix to get a Best Picture nod, and if it goes on to win the award, it would be first foreign-language film to do so. Yet even as the Academy attempts to grapple with its own relevance and blindspots, its nods this year largely ignored female filmmakers and several younger black directors. See the full list here.

Kamala Harris officially joins a crowded field of candidates vying to unseat President Donald Trump. In her campaign announcement, the California senator gestured at how she’ll differentiate herself from the rest of the pack—by eschewing a singular focus and trying to cobble together a broad coalition of support. Harris and other 2020 Democratic contenders will face some pressure to support impeaching Trump, as one prominent California billionaire looks to spend tens of millions of dollars to make the topic a major campaign issue.

Evening Reads

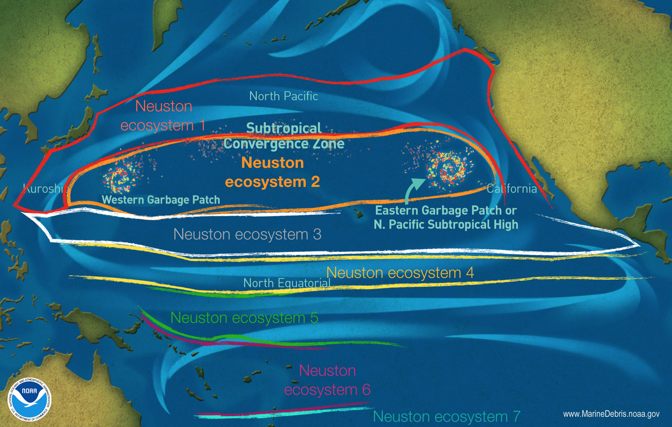

(A nudibranch. Image: Little Dinosaur / Getty)

There’s a whole ecosystem living at the ocean’s surface, and it may be at risk—from what seems to be a well-meaning but misguided attempt to clean up plastic.

→ Read the full story here

(David Sacks / Getty)

Do you have violent fantasies—of hurting a boss, or a bully, or a sworn enemy? While indulging in these thoughts might feel like a cathartic process, there’s research to suggest doing so really has the opposite effect.

→ Read the full story here

Our partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing city dwellers around the world. Gracie McKenzie shares their top stories:

The “Marie Kondo effect” is coming at a weird time for thrift shops: Netflix’s hit show has everyone tidying up, but that’s not the only reason second-hand stores are being flooded with donations.

There’s a growing consensus that our cities are becoming “childless.” But that’s not entirely true, Richard Florida writes. (Paris even has a plan to make life a little easier for its kids and families.)

Alabama’s Heritage Preservation Act forbade any city in the state from removing or altering Confederate monuments. Last week, circuit court Judge Michael Graffeo ruled that the law was unconstitutional, then retired the next day.

For more updates like these from the urban world, subscribe to CityLab’s Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

It’s Tuesday, January 22. This is the 32nd day of the partial government shutdown. The Donald Trump administration said it is exploring ways to keep providing assistance to the nearly 40 million Americans receiving SNAP benefits if the current stalemate continues into March.

In 2020 News: California Senator Kamala Harris announced on Martin Luther King Jr. Day that she’s running for president—and she’s positioned herself as the candidate who can put together the winning coalition Democrats have been obsessed with since their loss in 2016. Meanwhile, Tom Steyer, the billionaire Democratic activist and fundraiser, is launching a campaign to pressure 2020 candidates to support impeaching President Donald Trump. “If you’re against impeachment, don’t bother running,” Steyer said recently. “Save your time. Drive an Uber.”

Rebellion: The Los Angeles teachers’ strike, which saw some 30,000 educators on strike since the beginning of last week, is slated to end after union and city officials reached a tentative agreement on Tuesday. Since early 2018, the total number of teachers and other school staffers who have participated in labor strikes in the U.S. has reached at least 409,000. This wave of teacher activism is completely unprecedented, reports Alia Wong.

On the Docket: The Supreme Court ruled to temporarily allow the Trump administration’s ban on transgender people from serving in the military go into effect. The justices also agreed to take up a major gun case for the first time in almost a decade.

Also Read: This 2017 account from a transgender CIA officer, shortly after Trump tweeted a transgender military-service ban.

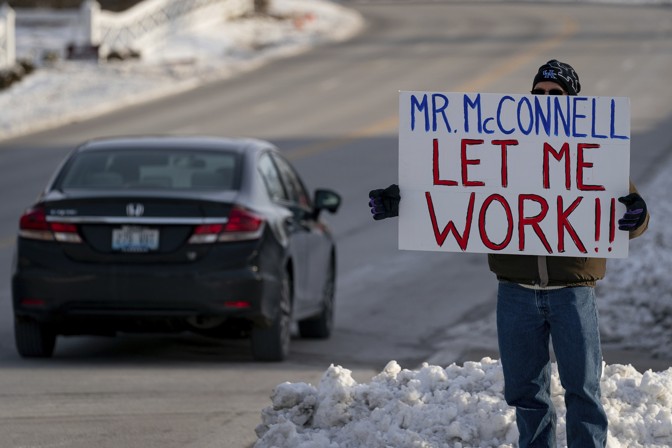

Snapshot

A furloughed EPA worker, Jeff Herrema, holds a sign outside the offices of U.S. Senator Mitch McConnell, in Park Hills, Kentucky. Bryan Woolston / AP

Ideas From The AtlanticWhat the Camp Fire Revealed (Annie Lowrey)

“People with very low incomes, the disabled, and the elderly are less likely to have technologies that might alert them to a fire speeding their way or a hurricane about to bear down. In part for this reason, the average age of those who died in the Camp Fire was estimated at 71.” → Read on.

Trump’s Hostage Attempt Is Going Miserably Wrong (David Frum)

“The shutdown was a demand for unconditional surrender. Unfortunately for him, the president lacks the political realism to recognize that he doesn’t have the clout to impose that surrender.” → Read on.

Stop Trusting Viral Videos (Ian Bogost)

“Film and photography purport to capture events as they really took place in the world, so it’s always tempting to take them at their word. But when multiple videos present multiple possible truths, which one is to be believed?” → Read on.

The Coast Guard During the Shutdown

“The problem is we don't actually have a shutdown. It's a semi-shutdown … a faux shutdown. The vast majority of the American public has no clue except maybe they've heard there's drama in Wash DC., or maybe they were on vacation but couldn't get in to see the Grand Canyon.” A reader who is part of a Coast Guard family shares a few thoughts with James Fallows.→ Read on.

◆ Iowa Prepares for the Mother of All Caucuses (Natasha Korecki, Politico)

◆ Covington Catholic Is the Terrible Sequel to the Kavanaugh Case (David French, National Review)

◆ Trump Preparing Two State of the Union Speeches for Different Audiences (Katherine Faulders, Jonathan Karl, and John Santucci, ABC News)

◆ The Young Left’s Anti-Capitalist Manifesto (Clare Malone, FiveThirtyEight)

◆ Trump’s Lawyer Said There Were ‘No Plans’ for Trump Tower Moscow. Here They Are. (Azeen Ghorayshi, BuzzFeed News)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily, and will be testing some formats throughout the new year. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

Beijing Daxing International Airport is a massive complex built on the outskirts of Beijing, China, from more than 220,000 tons of steel, with a price tag nearing 14 billion U.S. dollars, and is set for completion in September 2019. The new facility—billed as the world’s largest single-terminal airport—will be Beijing’s second international airport, and developers hope it will relieve pressure on overtaxed existing travel options. By 2025, planners say Daxing will be able to carry as many as 72 million passengers a year.

“Dear Noortje: Why, I sometimes wonder, do so many love letters start with ‘I meant to write sooner,’ or ‘I should write to you more often,’ or a more fanciful variation of the same?” reads a young man in Tara Fallaux’s short film. “Maybe because people are lazy and, in their daily lives, easily find an excuse for that laziness,” the man ventures, “while it’s harder to justify on paper. Maybe the reason is deeper.”

Those reasons and more are explored in the exquisite documentary Love Letters, from the Amsterdam-based production company HALAL Films. Fallaux trains the camera on various couples as they read each other heartfelt letters and openly discuss their relationship. We also hear from single people, who read letters they wrote to ex-lovers while reflecting on the trials and tribulations of these life-changing relationships. Love Letters is an intimate rumination on the project of love—and, ultimately, the virtues of vulnerability.

Fallaux got the idea for the film after receiving an unexpected love letter from a longtime friend. After considering it, the filmmaker decided to store the note in a box full of other important letters she’d previously received. “I realized what a treasure box it was,” Fallaux told The Atlantic. “It was a lifetime of stories, shared thoughts, feelings, and events I had forgotten about. While reading them, the letters brought me right back, almost like time-traveling.”

She began research on the film, only to quickly realize that finding subjects would be more difficult than she had anticipated. “Most of the people I spoke to loved the idea, and were happy to share their stories with me,” Fallaux said. “However, hardly anyone dared to participate in the film. Too intimate, too painful, too naked.” Eventually, the filmmaker found participants who were willing to step out of their comfort zone and appear on camera. According to Fallaux, the subjects that appear in the film “strongly believe in encouraging people to be more open in expressing their feelings and insecurities.”

“I was afraid my heart would be broken,” a young woman in the film offers her boyfriend, by way of explanation for her initial reticence about the relationship. “I was afraid that someone would get to know everything I don’t accept about myself.”

Another man reads a letter in which he struggles to find words to encompass his feelings for his ex-girlfriend. “Where did it go wrong?” the letter to the ex reads. “I don’t know. I’m unable to write to you because I still don’t know what to say. I’m afraid I won’t do justice to you, or to myself. To our time together.”

To illustrate how she feels about love letters herself, Fallaux quotes one of the young men from the documentary, who says that writing a love letter is akin to sharing a diary. “It’s something extremely personal,” Fallaux said. “Something that leaves you exposed. I think everyone has a need to be heard and noticed, so receiving a letter feels very precious. And it appeals to the senses. You can feel the paper, smell the ink, enjoy someone’s handwriting. And you can save it. The letter becomes an extension of the writer, capturing a particular moment in time that the receiver can keep forever.”

“Making this film,” she added, “is my ode to the strength of vulnerability.”

In Los Angeles, more than 30,000 teachers remain on strike; it took union and city officials more than a week to eke out a tentative agreement that, they announced Tuesday morning, will likely bring them back to their classrooms this week. Last Friday, teachers from a handful of public schools in Oakland, California, staged a one-day walkout, too, and they’re planning for another demonstration this Wednesday. Meanwhile, a citywide strike is brewing a few states over in Denver, as could soon be the case in Virginia, where teachers are gearing up for a one-day rally in Richmond later this month. An educator uprising is even percolating in Chicago, where the collective-bargaining process is just getting started: “We intend to bargain hard,” the teachers’ union’s president told the Chicago Tribune last week.

These protests follow many others around the country. Last February, roughly 20,000 teachers in all of West Virginia’s 55 counties walked out. A month or so later, teachers in Oklahoma boycotted their classrooms; Kentucky’s educators staged their own strike that same day in early April, as did their counterparts in Arizona a few weeks later, picketing for a week. Later, a one-day rally by teachers in North Carolina forced numerous school districts to cancel classes. And last month, unionized educators in one of Chicago’s largest charter networks walked off the job—the first strike of its kind in the country’s history.

Taken together, these strikes amount to an unprecedented wave of teacher activism. For several decades, teachers’ unions generally shied away from striking. While strikes occasionally cropped up due to frustrations over demanding requirements and stagnant pay, they typically did so as isolated blips, generating little attention beyond the affected locale. A similarly significant period of teacher strikes arguably hasn’t happened since 1968, when large-scale walkouts occurred in Florida, Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, and New York City, along with smaller-scale ones in cities such as Cincinnati and Albuquerque.

Even that wave pales in comparison with today’s. Inconsistencies in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ data-collection methods make it tricky to compare the two periods in quantitative terms. What’s clear, though, is that the eight major 2018 strikes—including the four high-profile statewide walkouts—involved a total of more than 379,000 teachers and school staff. Taking into account the current L.A. strike—which is poised to end after Tuesday, pending teachers’ ratification of their union’s newly inked agreement with the district—brings the tally to at least 409,000. The four major teachers’ strikes of 1968, by contrast, involved some 107,000 educators total, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics analysis.

If nothing else, education-policy scholars, legal analysts, and labor experts tell me this wave is unprecedented in the terms that matter most: the stakes, the sentiments, the long-term implications. The walkout in Los Angeles is distinct from its red-state predecessors of 2018 in many regards—its participants are effectively facing off against a Democratic-controlled school district and state, for example, and a plurality of them are Latino, including many whose activist roots run deep. Still, the impact of this strike, which has shut down the country’s second-largest school district for more than a week, amounts to much more than a disruption to classes for nearly 500,000 students. It could go as far as helping to solidify this sequence of strikes as a pivotal moment in a 21st-century labor movement that is characterized by its radicalism and sense of collective action, suggests Charlotte Garden, a professor at Seattle University School of Law who studies labor.

[Read: The unique racial dynamics of the L.A. teachers’ strike]

Back when teachers’ unions first rose to prominence in the early 20th century, the organizations were seen as white-collar guilds tasked with serving educators’ professional needs, Garden says. They were conceived as distinct from, say, the steelworker and coal-miner unions, which were known for their activist bent and narrative of class struggle. But in recent years, many teachers’ unions have been modifying their brand and their explicit mission, placing emphasis on issues beyond educators’ own pocketbooks. In last year’s West Virginia strike, for example, teachers decried students’ limited access to quality instruction; in Oklahoma, their targets were outdated textbooks and dilapidated facilities; in Los Angeles, they condemned the paucity of counselors and classrooms packed like sardines.

These issues “get at the heart of public education,” says Kent Wong, the director of UCLA’s Labor Center, meaning that, in a sense, teachers’ unions aren’t fighting just for teachers anymore, but also for students themselves. By expanding their demands beyond their own compensation, teachers’ unions are transforming into some of the most significant advocacy groups striving for socioeconomic equality in America today. As part of the tentative agreement announced Tuesday, the Los Angeles school district will shrink class sizes and better incorporate the real world into curricula on top of increasing teachers’ salaries by 6 percent.

This broader, more public-minded approach has its roots in 2012, and in a city well versed in teachers’ strikes: Chicago. The timing was hardly auspicious for an uprising: American taxpayers, whose support for unions in general had been declining, had started to see public-sector unions as incompatible with their interests as taxpayers; politicians from both parties were starting to place restrictions on such organizations. The impulse for many political leaders in the Windy City was thus to dismiss the walkout as unnecessary and superficial.

Yet, as Erik Loomis writes in his recent book on the history of strikes in the United States, money was an afterthought for Chicago’s teachers. Instead, echoing a landmark report their union had published earlier that year outlining the changes the students needed to thrive, teachers demanded more and better training for serving specific populations, as well as fair evaluations designed with kids’ success in mind; they called for air conditioning in their sweltering classrooms and lower limits on how many students could be placed into those classrooms.

The teachers wanted, Loomis writes, “to work and live with human dignity,” an objective the teachers’ union framed as inseparable from a similar sense of dignity among children both in and outside of school. After a week of boycotting their classrooms, the teachers secured some concessions from the district—including a carefully crafted evaluation system that relies partly on student test scores, textbooks for all kids on the first day of school, and a more holistic curriculum with a greater investment in extracurriculars such as art.

Since then, teachers’ strikes have continued to focus even more on these beyond-the-pocketbook issues. One reason is simply that the quality of the country’s public schools is, in certain places, terrible. The Great Recession ushered in an era of austerity measures that significantly hamstrung public schools across the country; in a handful of red states, school spending never returned to pre-2008 levels. Additionally, schools have been resegregating, contributing to growing race- and income-based disparities in achievement, and standardized testing, which proliferated following the No Child Left Behind Act signed into law by George W. Bush in 2002, continues to dictate the way many schools are measured and run.

At the same time, the American public maintains tepid attitudes toward unions in general and wariness of their political influence specifically; since the mid-20th century, there has been a general decline in union membership. These trends came into sharp focus last summer with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Janus v. AFSCME, which deemed it unconstitutional for public-sector unions to collect membership dues from workers who don’t support the union, a tactic on which they’d relied for decades. In light of this, teachers’ unions have sought to rebrand themselves as activist organizations charged with fighting for children’s needs in the name of the collective interest, an overhauled identity that has resulted in both more striking and more results.

Even so, critics suggest that self-interest is nevertheless what’s driving teachers’ unions to the picket lines. Jeanne Allen, the founder and director of the Center for Education Reform, a pro-charter-school organization, says that following Janus, “teachers are desperately afraid that if they have to go out and recruit members and convince them that [the unions] are worthwhile,” the unions won’t be able to collect the fees needed to sustain themselves.

As evidence, Allen cites the collective-bargaining proposal submitted by the L.A. teachers’ union earlier this month: It stipulated that the district would have to provide the union with the contact information of every LAUSD employee, for example, and restrict the number of activities for which schools can request teachers’ participation rather than leaving that up to individual campuses. In other words, the union may be attempting to keep a tight rein on staff who in a post-Janus world may choose to distance themselves from the union. The union is seeking to “micromanage the district,” Allen argues, by gaining more control over decisions that individual schools should have the power to make.

[Read: Is this the end of public-sector unions in America?]

Teachers concede that the walkout had been in the works for some time, but their motives, they argue, go beyond self-interest and beyond strengthening the union for the union’s sake. “People are pissed about the conditions in L.A.” says Pedro Noguera, a distinguished professor of education at UCLA whose research as a sociologist focuses on the impact of race and class on schools. By “conditions” he means the class sizes (some are as large as 46 students, exceeding the 39-pupil limit stipulated by teachers’ last contract), the lack of support staff (each high-school counselor in the district has an average caseload of nearly 400 students), and the rapid growth of charter schools (at 224, Los Angeles has more such institutions than any other U.S. city, and a number of studies, at least one of them union-funded, have found that the charter-school sector siphons hundreds of millions of dollars out of the union every year). “All those things come together to make people very angry,” Noguera said.

Beyond that, the six educators I spoke with in recent days all alluded to their growing realization that change won’t happen without major disruption. (Five of the teachers are in L.A., while one spearheaded the one-day walkout in Oakland, where the teachers’ demands placed a similar emphasis on charter schools and sorely deficient classroom conditions.) They’re not criticizing the growth of the charter sector—which in L.A. now enroll nearly 140,000 students—because such institutions operate beyond the union’s purview, they argue, but because they fear the sector is depleting the city’s public-education system at the hands of private, sometimes for-profit, entities. Public per-pupil funding follows students who transfer into charters out of the public schools, where enrollment has plummeted in recent years. The teachers contend that this trend has contributed to public schools’ deterioration in both the city and the state—largely attributable to a property-tax amendment passed in the 1970s commonly known as “Prop 13”— which once boasted one of the country’s best education systems.

“We’ve been in this fight since before Janus … We believe in this stuff,” says Arlene Inouye, one of the union’s chief negotiators and a former public-school educator, pointing to the overall decline in classroom conditions and highlighting the union’s leadership overhaul four years ago. In an interview, John Rogers, an education-policy professor at UCLA,suggested that more teachers in L.A.—and across the country—are starting to see themselves as “guardians of democracy.” While the legislative results of last year’s strikes have been mixed, various polls showed rising support nationally for teacher-salary hikes, strikes, and school-funding increases.

Still, even if L.A.’s teachers have broad support from the public, it remains unclear how their demands will be funded; as of Tuesday morning local time, details on the tentative agreement hadn’t been released. While union officials and some analysts pointed to the district’s nearly $2 billion in reserves, LAUSD maintained that the remaining money it has is already being spent or has been committed to critical expenditures, including pay raises and staffing increases that partly heed teachers’ demands. When we spoke last week, UCLA’s Noguera emphasized that he sympathizes with the teachers’ concerns and their impulse to walk out—but that he recognizes the district’s fiscal dilemma, too. Because the school district receives its per-pupil funding from the state, every day of the strike—with the declining rates of kids showing up to school—comes with an immense deduction in those public dollars. As of Friday, according to district data, LAUSD had lost close to $125 million in gross revenue. “If you’re really trying to fund public education, and the strike weakens the system,” Noguera suggests, “then you’re actually going to be weakening public education.”

The irony of it all is that the recent strikes transpired in a moment marked by waning public support for unions and widespread skepticism about their political influence, a Supreme Court decision that appears to side with a majority of Americans by restricting unions’ fundraising capabilities, and overly stretched state budgets that make many of teachers’ demands all but impossible to fulfill. Teachers are attempting to leverage these adverse realities to their advantage—and based on the public’s response, this unlikely strategy appears to be working.

The fifth episode of Tidying Up With Marie Kondo, Netflix’s effervescent new reality series, deals with Frank and Matt, a couple living in West Hollywood, California. Both writers, they have a touching love story involving Tinder, a too-small apartment filled with detritus from past roommates, and a burning desire to prove their adulting bona fides. They are, in short, the archetypal Millennial couple. The dramatic hook of the episode is that Frank’s parents are coming to visit for the first time, and Frank wants to impress them, to make them see “that the life we’ve created together is something to be admired.”

Frank and Matt, in other words, want their home to reflect their identities and sense of self (as opposed to the cutlery preferences of the people Matt lived with after college). They’ve internalized the idea that the signifiers of success are primarily visual. “I don’t know that I’ve given [my parents] any reason to respect me as an adult,” Frank agonizes at one point, which is absurd, given his apparently successful career and adorable relationship. “I’m organized in some aspects of my life. Like, professionally, my email inbox is organized, I’m great. And I just get frustrated with myself that I haven’t translated that into my home life. It feels like I give it all at work and then I come home and am like, pmph.” He makes a gesture like a deflated balloon.

If the viral success of Tidying Up With Marie Kondo is anything to go by, Frank and Matt—their exhaustion, and their understanding that an adult existence is an optimized one—aren’t anomalous in their anxieties. Kondo, a Japanese organizational consultant, has sold more than 11 million books in 40 countries since the publication of her magnum opus, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. Compared to the interest in her television series, though, Kondo’s previous achievements are a relative blip. Netflix didn’t respond to queries about how many people had viewed Tidying Up, but in the U.S. at least, the show’s release has sparked a feverish curiosity about Kondo and her practices.

More than 192,000 Instagram pictures of color-coded sock drawers and neatly labeled mesh containers now bear the #KonMari hashtag. Thrift stores around the U.S. have reported record donation hauls as inspired Americans streamline their possessions. In barely three weeks, Kondo has gone from a best-selling author to a cultural juggernaut. In part, this is due to Netflix’s prodigious reach, particularly among young Millennials, who are five times more likely to watch a show on the streaming service than access it via any other provider. But the success of Tidying Up also speaks to how neatly some episodes of the show sync with its cultural moment, a time in which identity and achievements are visual metrics to be publicly displayed and curated, and a happy home is a perfected, optimized one.

[Read: ‘Tidying Up With Marie Kondo’ isn’t really a makeover show]

For Millennials like me, people born roughly between 1981 and 1996, the desire to flaunt our tidying prowess isn’t just about showing off. A 2017 study by the British researchers Thomas Curran and Andrew P. Hill found that Millennials display higher rates of perfectionism than previous generations, in part because we’ve been raised with the idea that our future success hinges on being exceptional. But, as Frank suggests, we’re also struggling with what it means to really grow up. The aspirational markers of adulthood used to be relatively straightforward: graduation, marriage, children, homeownership, a 401(k). But now that Millennials are so overloaded with student debt that we struggle to buy places to live, adulthood is more complicated. It’s more performative. It’s #KonMari.

Four days after Netflix released Tidying Up, BuzzFeed News’s Anne Helen Petersen published what feels like a seminal analysis of a connected phenomenon. “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation” elegantly and systematically documents how the malaise Frank complains about—putting so much effort into his work that he has nothing left for himself—is symptomatic of a much larger generational disorder. Millennials, Petersen argues, have been raised with the belief that they have to be exceptional, or they won’t succeed in an economy that since the early 2000s has seemed to dance perpetually on the edge of an abyss. “I never thought the system was equitable,” she writes. “I knew it was winnable for only a small few. I just believed I could continue to optimize myself to become one of them.”

This conviction is why Tidying Up With Marie Kondo has drawn so many fans in such a short time, and why your feeds might suddenly be bloated with soaring piles of clothes and arguments about whether to Kondo your books. Millennials have come to believe, Petersen writes, that “personal spaces should be optimized just as much as one’s self and career.” But the conspicuous nature of #KonMari also suggests a larger vacuum. Millennials don’t just gravitate to Marie Kondo because they don’t have apartments big enough to own things. What Tidying Up offers is both a counterpoint to the way they’ve been raised (less is more, versus more is always better) and an endorsement: The promise, at least as Millennial culture seems to have interpreted it, is that if people work to organize their lives to look just right, the rest will follow. The performance of the self has become more important than the reality. Even TV has noticed.

If Marie Kondo is the high priestess of burned-out Millennials, Fyre Festival was their summer solstice. In 2017, a large adult grifter named Billy McFarland partnered with the rapper Ja Rule to sell tickets to a festival in the Bahamas that promised to be the apotheosis of an Instagram-worthy event: megastars (Kendall Jenner, Bella Hadid); spectacular food; luxe but eco-friendly accommodations; music by Major Lazer, Migos, and Blink-182. McFarland partnered with a marketing company called Jerry Media that paid supermodels to promote the event on their social-media accounts, cultivating the sense that Fyre Festival would be the exclusive gathering for stars that any schmo could also buy a ticket to.

The seeds of Fyre Festival’s success were also its downfall: When attendees finally arrived at what turned out to be the gravelly parking lot near a Sandals resort, they documented everything they found on social media. Like the fact that the only places for people to sleep were unassigned FEMA tents with pallet mattresses. And that instead of luxurious communal bathrooms with showers, there were porta-potties. The most iconic post from Fyre Festival, in the end, was a picture of a sandwich: plain bread with two slices of slimy American cheese, accompanied by the hashtags #fyrefraud and #dumpsterfyre.

A car crash in slow motion, Fyre Festival was a catastrophe on such a colossal scale that two documentaries, released within days of each other, are trying to make sense of it. Netflix’s Fyre, as my colleague David Sims has written, takes a relatively straightforward approach to excavating the whole fiasco, accounting for not only McFarland’s crimes and the public spectacle of the festival’s monumental collapse, but also the Bahamian workers who still haven’t been paid for their efforts.

[Read: Why people paid thousands of dollars to attend a doomed music festival]

Fyre Fraud, surprise-dropped by Hulu last Monday, takes a different approach. Directed by Jenner Furst and Julia Willoughby Nason, it mines the sociological implications of Fyre Fest, and what it says about a generation of Americans that they’re so susceptible to a scammer with an Instagram account. Fyre Fraud includes parts of a taped interview with McFarland himself (who was supposedly paid for his participation), but they’re the least revealing moments in the documentary. More interesting is how Fyre Fraud uses the selling of the festival to consider the ways some Millennials understand identity, including their anxieties about affirming their existences online—literally, Pics or it didn’t happen.

Fyre Fraud posits that, for all the sloppiness of his grift, McFarland actually has a surprisingly intuitive sense of what Millennials want, and how to market it to them. Having been raised with the sense that being exceptional is the only way to thrive, Millennials can be hyperaware of their own status relative to others, and ferociously invested in elevating themselves above the pack. As preposterous as the Fyre Festival promotional video might seem now, it pings all the right dopamine receptors in an ongoing loop of stick (the acute FOMO of knowing everyone important is somewhere doing something fabulous without you) and carrot (countless Instagram opportunities for personal branding and self-curation). Influencers, the New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino says in Fyre Fraud, are people who have refined and monetized the art of this “performance of an attractive life.”

Which brings us back to the perfectionism study. Millennials, born during the Reagan, Bush Sr., and Clinton presidencies, are the first real babies spawned by neoliberalism and its overarching message of competitive individualism. Curran and Hill wanted to establish whether growing up amid these ideologies made Millennials more likely to be perfectionists, and therefore more likely to be depressed, anxious, unhappy, and dissatisfied with themselves. They concluded not only that perfectionism rates have risen, but also that Millennials’ identities have been fractured by shifting cultural values.

Even as they’re poorer, Millennials are more materialistic: 81 percent of Americans born during the 1980s say that accruing wealth is among their significant life goals, more than 20 percent higher than previous generations. As a national belief in the collective has given way to an emphasis on the individual, Millennials have had to become less inhibited about the pursuit of self-gain, and more shrewd about how they define themselves. Amplified by social media, such perfectionism urges the posting of absurdly idealized images, which, transmitted, reinforce the cycle of unrealistic physical ideals and a sense of alienation. “Neoliberalism,” Curran and Hill conclude, “has succeeded in shifting cultural values … to now emphasize competitiveness, individualism, and irrational ideals of the perfectible self.”

The messages that Millennials in the Western world were raised with, in other words, have taught them to work harder and better than ever before, in all aspects of their lives. And that work is making a generation miserable, as Petersen documents, as they strive to attain success and avoid failure, and are permanently attuned to the perceived expectations of others. They’ve constructed flimsy charades of identities based on what they think other people will want. They want to prove that their lives, as Frank says in Tidying Up, are things to be admired, and that their homes, vacations, children, closets all function as projections of their best selves: organized, attractive, authentic. Unattainable.

Roma and The Favourite led the Oscar nominations with 10 apiece as the Academy Awards unfurled their shortlist Tuesday morning, with Best Picture recognition for A Star Is Born, BlacKkKlansman, Green Book, Black Panther, Vice, and Bohemian Rhapsody. Some surprising snubs abounded in a race that never quite settled on an obvious front-runner: Bradley Cooper (A Star Is Born) and Peter Farrelly (Green Book) missed out on crucial Best Director nods, and stars such as Emily Blunt, Timothée Chalamet, and Ethan Hawke were overlooked in the expected acting categories. But there were multiple industry milestones, including Roma becoming the first Netflix film to get a Best Picture nomination and Black Panther becoming the first comic-book movie to do so.

An unsettled and politically charged awards season has, for the past few years, been the name of the game at the Oscars. But even by those standards, the 2019 nominee list is the product of a tumultuous campaign that often seemed to reckon with the future of Hollywood, be it the disruptive power of Netflix, the enduring but increasingly out-of-date appeal of “prestige” films like Green Book, and the Academy’s own anxieties about its declining influence. A misguided attempt at establishing a “popular film” award has been set aside for now; the question of who, if anyone, will host the February 24 ceremony remains unanswered after Kevin Hart was hired and then stepped down over a history of homophobic tweets.

Early on, the Best Picture conversation was dominated by A Star Is Born, Cooper’s Lady Gaga–starring remake of the Hollywood classic, which connected with both audiences and critics, grossing more than $400 million worldwide despite being an R-rated drama. Though the film got many nods (including for Cooper, Gaga, and Sam Elliott in the acting categories), it missed the pivotal directing and editing shortlists, suggesting a lack of enthusiasm across all the Academy’s branches, something reinforced by the film’s failure to win major prizes at precursors like the Golden Globes.

Green Book, which won a Best Picture trophy at the Globes as well as the coveted Producers Guild award, had recently pulled ahead despite its mediocre box-office takings and more mixed critical reception. A heartwarming tale of friendship between the black musician Don Shirley and his white bodyguard, Tony Vallelonga, in the early 1960s, the film has been dogged by controversy, including complaints from Shirley’s family over perceived inaccuracies, the reemergence of old stories about the director Farrelly’s inappropriate behavior in the past, and the unearthing of an anti-Muslim tweet by the screenwriter Nick Vallelonga (Tony’s son). Green Book still seems like a viable competitor, especially for Best Supporting Actor (Mahershala Ali), but its lack of a Best Director nod will hurt its chances for the biggest prize.

The Favourite, Yorgos Lanthimos’s arch period tale of scandal and intrigue in the court of England’s Queen Anne, received an expected slew of technical nominations along with recognition for Lanthimos and the entire leading cast (Olivia Colman, Rachel Weisz, and Emma Stone), bumping the film to the top of the nomination tally. BlacKkKlansman, Spike Lee’s rendering of Ron Stallworth’s autobiography about his infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan in 1970s Colorado, was a hugely successful comeback for the celebrated filmmaker, earning him his first competitive directing nomination (along with a screenplay nod) and six nominations in total. Bohemian Rhapsody, the other big Golden Globes winner, was shortlisted for Best Picture, Best Actor, and three technical awards, but its director, Bryan Singer (who was fired during production), was ignored.

Perhaps the biggest story of the nominations, though, is the dominance of Roma, a Mexican film from Oscar winner Alfonso Cuarón (Gravity), which has a significant chance to be the first foreign-language feature to win Best Picture in the Academy’s 91-year history (the movie’s dialogue is in Spanish and Mixtec). Netflix has thrown a tremendous publicity budget behind the film’s campaign machine, partly to overcome a perceived bias against the streaming company for mostly keeping its movies out of cinemas. The company also broke its long-standing rules and released Roma in theaters first to get ahead of that criticism. Netflix’s efforts seem to have worked: Roma was recognized not just in technical categories but also for Best Actress (newcomer Yalitza Aparicio) and Supporting Actress (Marina de Tavira), the latter of which was a massive surprise. As other potential front-runners founder, Roma might end up as the consensus pick.