Quando ouviu que era a “galinha dos ovos de ouro”, Murilo entendeu como um elogio. Não viu malícia no comentário do então chefe, Francisco Neivan Alves da Silva, por ser o melhor vendedor porta-a-porta de iogurtes e outros lácteos da equipe de Salto, no interior de São Paulo. Ficou feliz por ter deixado para trás o emprego informal de servente de obras no interior do Ceará, mas não imaginou que seria vítima de uma rede de tráfico de pessoas que o levaria a condições de trabalho análogas à de escravo, com jornadas de 14 horas diárias, descontos salariais e alojamento precário.

No primeiro mês no novo emprego, ele já não receberia o pagamento de R$ 2,2 mil prometido por Silva. Teve R$ 500 descontados “porque a situação piorou com a crise econômica”, na versão do patrão. E aquele foi só o começo de uma série de violações trabalhistas que terminou com o resgate de 28 trabalhadores em condições análogas à escravidão envolvendo duas gigantes do setor alimentício: a Nestlé e a Danone.

A história de Murilo, que pediu anonimato, foi descoberta por auditores-fiscais do Ministério do Trabalho em fiscalizações que aconteceram entre março e julho de 2018 no interior de São Paulo. Silva, que trazia cearenses do interior com falsas promessas para trabalhar como vendedores de iogurtes, foi preso em abril pela Polícia Federal de Sorocaba, acusado de “tráfico de pessoas para fins de trabalho em condição análoga à de escravo”.

Danone e Nestlé foram corresponsabilizadas pela prática de trabalho escravo por não monitorarem suas cadeias de distribuidores e tiveram que pagar parte das verbas rescisórias dos resgatados – a Danone pagou R$ 185 mil e a Nestlé, R$ 139 mil, segundo relatório dos auditores. “Foi uma cegueira deliberada. As empresas lucraram com o esquema fraudulento e foram cúmplices”, diz o auditor-fiscal do Renato Bignami, que participou das fiscalizações.

O esquema econômico que sugou Murilo e que atrai tantos outros ambulantes movimenta milhares de reais e toneladas de produtos perto da validade, com preços acessíveis para as classes D e E. É chamado de “crediário”, pois funciona com vendas à crédito para o comprador final, e conta com uma complexa rede de distribuidores e subdistribuidores nas periferias das grandes cidades e em cidades do interior. A investigação do Ministério do Trabalho, que aconteceu em parceria com a Polícia Federal, apurou que, para a Danone e a Nestlé, o escoamento desses produtos quase vencidos representa cerca de 2% do lucro das empresas no Brasil.

A Dairy Partners Americas Brasil, que responde pela Nestlé, informou em nota que encerrou o relacionamento comercial com o microdistribuidor autuado pelos auditores-fiscais em julho de 2018, quando soube das irregularidades. A empresa afirmou ainda que não tolera “violações aos direitos humanos e trabalhistas”.

Já a Danone Brasil informou que “repudia qualquer forma de trabalho que contraria os direitos trabalhistas” e não tem relação comercial com o microempresário autuado, já que ele “adquire os produtos por meio de seus clientes ocasionais”. A Danone reitera seu compromisso com a legislação vigente e reforça seu comprometimento na prevenção e combate ao trabalho escravo em sua extensa cadeia produtiva”, disse a empresa.

‘Vendi R$ 500 mil e ganhei um danone’De porta em porta, os ambulantes ofereciam kits de iogurtes com 33 unidades por R$ 40 – ou R$ 1,21 por embalagem. Em grandes mercados, a unidade pode custar R$ 2. A jornada de trabalho mínima era de 14 horas diárias, mais as duas gastas no deslocamento. Começava às sete da manhã. Sob sol forte ou tempestade, eles empurravam os iogurtes em ruas montanhosas nas periferias e muitas vezes arriscavam a vida ao passar diante de traficantes armados. Murilo vendia mais de 70 kits por dia, o equivalente a R$ 50 mil por mês.

Se os vendedores de Silva precisassem de dinheiro em uma emergência – como quando o filho de Murilo teve uma estomatite grave –, o patrão emprestava, mas cobrava o dobro. Se faltassem no serviço por doença, tinham R$ 100 descontados do salário. Com tantos descontos, teve mês que Murilo nem recebeu. Precisou se endividar com o chefe para comprar comida para a família. “Cheguei a vender mais de R$ 500 mil em um ano, fui a ‘galinha dos ovos de ouro’. E sabe o que eu ganhei? Um pacote de danone para o meu filho”, lamenta.

‘Cheguei a vender mais de R$ 500 mil em um ano. E sabe o que eu ganhei? Um pacote de danone para o meu filho.’No alojamento que Silva alugou para os trabalhadores, houve infestação por carrapato. Os trabalhadores se amontoavam em uma casa de dois cômodos abafada, sem roupa de cama, toalha ou comida. As condições degradantes e as jornadas exaustivas, colocando em risco a segurança, a saúde e vida dos trabalhadores, caracterizaram trabalho análogo ao de escravo, conforme o artigo 149 do Código Penal.

Dos produtos vendidos pelos ambulantes de Silva, 40% eram da Danone e 30% da Nestlé. Os caminhões das empresas descarregavam toneladas de iogurtes diretamente no galpões dos microdistribuidores. Joseilton Ferreira, um desses microdistribuidores, comprava da Danone e repassava para crediários, como o de Silva. Entre outubro de 2017 e novembro de 2018, Ferreira comercializou R$ 1,8 milhão em iogurtes próximos à data de vencimento da marca. Já os iogurtes da Nestlé chegavam por meio da empresa Baturitense Comércio de Alimentos. De outubro a março, a joint venture Dairy Partners America, ligada à Nestlé, faturou R$ 145 mil em produtos para a Baturitense – o equivalente a 26 toneladas de iogurtes.

A venda dos produtos, com forte apelo para crianças, era fiado. Por isso o vendedor tinha uma ficha de papel para cada cliente, onde anotava as compras e os pagamentos a vencer. Vendas acima de R$ 50 não eram proibidas, mas se o cliente não pagasse, o vendedor era obrigado a assumir o ônus, depois descontado do salário. E eram muitos os clientes que davam calote e faziam ameaças, segundo os trabalhadores ouvidos pela reportagem.

Cada vendedor carregava mais de 100 quilos de alimentos, todos os dias, dentro de um isopor.

Foto: Programa Estadual de Combate ao Trabalho Escravo

Os microdistribuidores que recebiam toneladas de iogurtes diretamente das empresas e que abasteciam crediários como o de Silva constavam no departamento de vendas das empresas, ao lado dos grandes distribuidores. Tanto a Danone quanto a Nestlé criaram uma nomenclatura nova para esse grupo. Na Danone, “cliente-consumidor” ou “spot”. Na Nestlé, clientes BOP, corruptela de “base da pirâmide”.

Na prática, afirmam os fiscais, as multinacionais deixaram de monitorar os microdistribuidores e, assim, de adotar mecanismos de prevenção de direitos fundamentais. A conduta e omissão das empresas, ainda que involuntária, agravou o risco de exploração da força de trabalho. “Essas falhas contribuiram seguramente para que as violações ocorressem”, afirmou Bignami.

Não é possível datar quando essa caracterização corporativa aconteceu, mas a investigação dos auditores mostra que os crediários com venda porta-a-porta de produtos quase vencidos existem há quase duas décadas. A auditoria segue investigando outros crediários.

Por causa dos descontos, nem no primeiro mês Murilo recebeu o salário prometido. Foto: Fernando Martinho

Fernando Martinho

Além de descumprir acordos internacionais em direitos humanos e do trabalhador que o Brasil é signatário, tanto Danone quanto Nestlé também infringiram acordos globais assumidos por suas respectivas matrizes na Europa – França e Suíça, respectivamente. “No exterior, haverá um impacto de reputação muito grande, que pode afetar as operações das empresas. A partir desse impacto de reputação, espera-se que medidas públicas sejam tomadas”, afirma Tamara Hojaij, pesquisadora do Centro de Direitos Humanos e Empresas da Fundação Getúlio Vargas.

Com o fechamento do crediário, Murilo vive de bicos. Sem o segundo grau completo, diz, ninguém quer empregá-lo. “Em dia que não trabalho, fico pensando: e se meu filho pedir um pão para comer, o que eu falo para ele? Eu passei muita fome do Ceará. Não queria que meus filhos sofressem o mesmo.”

The post Iogurtes quase vencidos da Danone e Nestlé são vendidos com trabalho escravo appeared first on The Intercept.

The U.S. military is moving ahead with plans to collect and destroy unused firefighting foam that contains the hazardous chemicals PFOS and PFOA. But in trying to solve one environmental problem related to these persistent chemicals, which have caused massive drinking water contamination, the Defense Department may be creating another.

More than 3 million gallons of the foam and related waste have been retrieved from U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, National Guard, Army, and Air Force bases around the world. Now the question is what to do with them. Known as aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, it was originally created to put out jet fuel fires. AFFF is flame-resistant by design and contains PFAS chemicals, such as PFOA and PFOS, which cause a wide range of health problems and last indefinitely in the environment.

For decades, the military has been using AFFF to put out fires and to train military firefighters; that training involved spraying the foam onto blazes that were purposefully set in pits, many of which were unlined. From there, PFOS, PFOA, and other chemicals in their class seeped into groundwater in and around U.S. military bases at home and abroad.

Because of environmental concerns about the chemicals, which are associated with kidney cancer, testicular cancer, immune dysfunction, and many other health problems, the Air Force decided in 2016 to stop using foam that contained PFOA and PFOS, and began replacing the foam at installations worldwide. Unfortunately, as The Intercept reported last year, the new foam contains only slightly tweaked versions of the same problematic compounds, so it is likely to present many of the same health and environmental risks.

For the Air Force, the question of how best to dispose of the old foam comes too late. In January 2017, a waste disposal company hired by the Defense Department began incinerating more than 1 million gallons of the foam and AFFF-contaminated water that had been collected from Air Force bases around the country. According to the contract, the incineration was to be complete by this month.

But that leaves more than 2 million gallons of foam and contaminated water from other branches of the military, as well as unknown quantities possessed by nonmilitary airports and firefighters, which some states have recently begun to collect.

Dangerous ByproductsAlthough incineration is the military’s chosen disposal method, there has been little research on the safety of burning the foam. Two studies concluded that the incineration of PFAS chemicals would not be a source of further contamination, but both were funded by companies with a vested interest in making the problem go away. The first study was funded by DuPont, which used PFOA in the production of Teflon. The second was funded by 3M, which developed AFFF in partnership with the Navy in the 1960s and was the military’s exclusive supplier of AFFF for decades.

But some of the scant research on the topic suggests that incineration may not fully destroy PFAS. After PCBs were found in chicken eggs laid near an incinerator, a 2018 study determined that PFOA was released into the air by a municipal incinerator in the Netherlands. The author concluded that “modern incinerators cannot fully destroy” PFOA, PCBs, and other persistent chemicals.

The Air Force itself acknowledged in a 2017 document that the foam, which was designed to resist extremely high temperatures, is hard to burn and that “the high-temperature chemistry of PFOS and PFOA has not been characterized, so there is no precedent to predict products of pyrolysis or combustion, temperatures at which these will occur, or the extent of destruction that will be realized.”

Even more concerning, “environmentally unsatisfactory” byproducts may be created by incinerating the foam. Among the highly toxic byproducts of PFAS incineration are hydrofluoric acid, which burns human skin on contact; perfluoroisobutylene, a chemical that so reliably kills people within hours of being inhaled that it’s been used as a warfare agent; as well as dioxins and furans, which cause cancer.

Unfortunately, by the time the Air Force acknowledged the serious potential dangers of incinerating the firefighting foam, it had already burned much of its AFFF stockpile.

In November 2018, the Defense Department entered into two contracts with Tradebe, an Indiana-based company, to incinerate more than 1 million gallons of stockpiled foam that had been collected from the Army, Navy, National Guard, and Marine installations in Italy, Spain, Bahrain, Greece, Romania, Japan, Korea, Cuba, Djibouti, and the U.S. But that foam has yet to be incinerated, according to Edith Terolli, a Tradebe spokesperson.

The Defense Department “has issued no service orders to Tradebe under either of the contracts,” Terolli wrote in a statement to The Intercept. “If DLA [the Defense Logistics Agency] issues a service order, Tradebe can ensure that all management practices will be conducted in full compliance with and on the basis of established regulations. Tradebe’s priority is safety and the protection of people and the environment.”

According to the Defense Department’s Logistics Agency, the AFFF will be sent to five or six hazardous waste incinerators.

A Heritage Thermal Services incinerator spews smoke from its smokestack close to nearby homes on Feb. 25, 2003, in East Liverpool, Ohio.

Photo: Tony Dejak/AP

The track record of the hazardous waste incinerator that burned the Air Force’s AFFF stockpiles adds to the environmental concerns about its destruction. Located on the Ohio River, the Heritage Thermal Services hazardous waste incinerator in East Liverpool, Ohio, has a history of violating environmental laws.

Alonzo Spencer, a lifelong East Liverpool resident, co-founded a community group to prevent the incinerator’s construction in 1982. “We never wanted it here,” said Spencer. “We were worried about the emissions from the stack.”

After more than 25 years in which the incinerator has released pollution into the air over East Liverpool, the community’s fears turned out to be well-founded. “The concerns that we raised from the health side have come to fruition,” Spencer said recently. Environmental Protection Agency records show that the Heritage facility has emitted dangerous chemicals — including cadmium, chromium, mercury, lead, and PCBs — above safety levels.

A 2017 study showed that children in East Liverpool who had elevated levels of one of the neurotoxic pollutants in their air, manganese, had lower IQ scores. The area had elevated numbers of children in special education classes — 19 percent as opposed to 13 percent statewide.

In 2013, the East Liverpool incinerator exploded, setting off multiple fires and spewing toxic ash into the neighborhood, which has twice the national poverty rate. Even after the EPA sent Heritage a letter in 2015 detailing 195 violations the company had committed, the dangerous emissions continued. The EPA’s website, which publishes the quarterly regulatory status of incinerators for the previous three years, classifies the East Liverpool plant as a “high priority violator” of the Clean Air Act for each of the 12 quarters listed, which means that the facility may pose a “severe level of environmental threat.”

And according to an October consent decree between Heritage and the EPA, the East Liverpool incinerator “violated, and continues to violate” various emissions limits set under the Clean Air Act. The consent decree, which settled a civil complaint that the EPA filed against Heritage in October, required the company to pay a fine and take numerous steps to limit its air pollution.

Two of the violations in the complaint raise particular concerns for the combustion of AFFF. The Heritage facility emitted chemicals known as dioxins and furans, which can be produced while burning PFAS. And, perhaps most concerning, the incinerator in East Liverpool failed to maintain minimum temperatures specified in the incinerator’s permit “on numerous days beginning on or before January 6, 2011 and continuing thereafter,” according to the EPA complaint. The failure to reach minimum temperatures can result in incomplete combustion and the production of dangerous byproducts.

Asked why it awarded a contract to a facility that was a high-priority violator of the Clean Air Act, the Defense Logistics Agency provided a written response stating that “as part of our due diligence facility vetting processes, we validate facility compliance with the regulatory authorities,” and that environmental authorities in Ohio “did not find any violation of … laws or rules and/or violations of Heritage’s permit conditions.”

Heritage did not respond to numerous emails and phone calls requesting comment for this story.

No GuidelinesTwo incineration experts contacted by The Intercept said that PFAS could be burned safely as long as the incinerator maintains the proper temperature for the correct amount of time. While both experts offer slightly different minimum temperatures, they agree that precise control of conditions is essential — and that the quality and past conduct of the company carrying out the work is important.

“I would want to know that the facility has a good track record of good solid operation,” said Marco Castaldi from the City College of New York. Giving a massive amount of AFFF to a company that has a history of serious environmental violations, Castaldi said, “is like taking your car to a mechanic that fails to tighten the bolts on the tire.”

According to Roland Weber, a German chemist and expert in the incineration of PFAS and related chemicals, if the incinerator isn’t sufficiently hot, highly toxic compounds could form and be released during the large-scale incineration of PFAS. “It’s a question about these smaller molecules, which are highly volatile and you cannot catch with filters,” he said.

Others feel that not enough is known about incinerating AFFF to do it on a large scale, regardless of the facility. “There are too many data gaps to argue that burning is safe,” said Jen Duggan, a lawyer at the Conservation Law Foundation in Vermont. Duggan notes that there is no official protocol laying out how to burn the chemicals — and no way of checking on the process after it’s complete.

“Even if we did know what conditions are required to destroy PFAS, we don’t have monitoring at the stacks to make sure it’s being done properly,” said Duggan.

Because PFAS have yet to be regulated, it’s especially difficult to ensure their safe destruction. “Usually, with incineration, you have the threat of liability to motivate some level of compliance,” said Sony Lunder, a senior toxics adviser for the Sierra Club.

With regulated chemicals, “you have protocols that require you to incinerate at certain temperatures. If you blow it, you violate your permit, which can result in EPA enforcement. And that can involve a fine,” said Lunder. “But PFAS are as regulated as Ivory soap.”

In November, concerns about a lack of protocols and the violations at Heritage’s East Liverpool incinerator helped stymie a plan to send firefighting foam collected in Vermont to the Ohio facility.

Vermont had collected some 2,500 gallons of AFFF from firehouses around the state that it was planning to send to the Heritage incinerator. The foam had already been loaded on a trailer when the state reversed its decision due to concerns about burning AFFF in general and at the Ohio facility in particular.

The unused foam has since been stored at a hazardous waste facility. According to Chuck Schwer, director of the Waste Management and Prevention Division at Vermont’s Department of Environmental Conservation, the AFFF will soon be shipped to a cement kiln incinerator that can burn it at a higher temperature.

Other states may soon start destroying their own foam too. Massachusetts began collecting unused AFFF in May. And in Ohio, the state fire marshal recently wrote to fire stations and encouraged them to collect their AFFF and send it to hazardous waste incinerators.

But environmental advocates are questioning what should happen with unused foam in states. “We don’t want it sent for incineration,” said Laurie Valeriano, executive director of Toxic-Free Future. The group is based in Washington state, where the Department of Ecology is seeking funding from the legislature to collect unused AFFF.

Up in SmokeEven as questions about incineration persist, both the military and some states are moving fairly quickly to destroy their unused AFFF. In New York, where collection of the foam is ongoing, the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation had already “properly disposed” of more than 25,000 gallons by last summer, according to the agency’s website. The department did not answer questions about exactly when, where, and how the AFFF was destroyed.

It’s understandable that people want to get rid of the toxic foam, but the sudden haste seems to be motivated by more than environmental concerns. Although PFAS chemicals are not currently regulated, this month three members of Congress from Michigan introduced the PFAS Action Act, a legislation that would classify the chemicals as hazardous substances and make polluters liable for their cleanup.

The Defense Department, which is responsible for hundreds of bases where AFFF has seeped into water, has been sued over the contamination and is engaged in a huge and costly effort to address the mess created by the foam. But because there are no binding safety levels for the chemicals, the Defense Department hasn’t had a clear legal obligation to clean up to any particular standard.

“We’re doing it because we’re good stewards and concerned citizens,” Maureen Sullivan, the Defense Department’s deputy assistant secretary for environment, told me about the U.S. military’s PFAS remediation work in a 2017 interview. “We have no requirement because it’s only an advisory.”

The PFAS Action Act, which would enable PFAS chemicals to be cleaned up through the Superfund program, would change that — and could potentially cost the military heavily.

“Everyone knows what’s coming and that DOD is trying to wiggle out of liability,” said Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics. “That’s why they want it burned. If you bury it, that does not erase the liability. But if you burn it, you burn the liabilities along with the chemicals.”

A bipartisan task force formed in the House of Representatives last week to address PFAS-related issues will likely tackle disposal issues as it pushes for accountability for polluters, including the Defense Department. Meanwhile, environmentalists are asking for careful scrutiny from them and other lawmakers before any more AFFF is burned.

“We need to pause and take a deep breath until we know that burning AFFF is safe and that we’re not putting others in harm’s way,” said Duggan of the Conservation Law Foundation. “If you ship foam to another community and incinerate it without complete destruction, you’ve just turned it into another public health risk.”

The post The U.S. Military Plans to Keep Incinerating Toxic Firefighting Foam, Despite Health Risks appeared first on The Intercept.

President Donald Trump speaks to reporters before boarding Marine One on the South Lawn of the White House on Jan. 19, 2019 in Washington, D.C.

Photo: Pete Marovich/Getty Images

President Donald Trump and his administration lie to and mislead the public as a matter of course. It’s a concerning but indisputable fact. So how do we combat propaganda and lies in our post-truth world?

The popular pre-Trump solution among news media outlets of fact-checking in real time — explaining to the public in dry, dispassionate language what’s true and what’s not — has proven ineffective and farcical at a time like this. In the bustling business of publicly fact-checking Trump, the Washington Post has counted more than 8,000 “false or misleading claims” from the 45th president. But that isn’t stopping his lies. However well-intentioned, the “Pants on Fire!” graphics are the equivalent of, in the eloquent words of antihero Erlich Bachman, bringing piss to a shit fight.

Consider the recent tweet from Trump about prayer rugs found near the U.S.-Mexico border: Its foundation was a report that — no joke — was based on the word of an anonymous rancher passing on what she said she heard from unnamed sources in the U.S. Border Patrol. How do you even fact-check such a claim?

Now, though, there might be a better battlefield for this information war: the courts.

The Information Quality Act requires government agencies to meet the same standards your local community college requires of its students.The Information Quality Act, sometimes referred to as the Data Quality Act, is an obscure law enacted in 2001 as a rider in a spending bill. The initial idea behind the legislation was to guarantee that agencies of the U.S. government are held to reasonably high information-quality standards as more and more of their reports and data were made available on the internet.

The legislation directed the Office of Management and Budget to establish standards for information distributed by U.S. government agencies. The guidelines require information published by U.S. agencies to be objective and honest, with any analysis based on clear and transparent methodology.

Indeed, there’s nothing radical about the guidelines. Basically, they require government agencies to meet the same standards your local community college requires of its students. But the law also provides for a remedy: If a federal judge can be persuaded that an agency’s published information does not meet the standards, the judge can order the report to be removed and retracted.

Such an order has never been issued, largely because the Information Quality Act is a law with very little history of litigation. Before Trump’s election, special interest groups tried unsuccessfully to use the law to undermine distribution of government research they simply disliked. The libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, for example, tried to force the Commerce Department, which includes the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to halt distribution of the 2002 U.S. Climate Action Report.

Trump, however, has ushered in a new hope of relevancy — and use — for the law. We’ve never had a presidential administration whose lies are as frequent and blatant as this one’s. While previous administrations have certainly told lies, including some very big and consequential ones, the Trump administration is without equal in its prolific output of propaganda that can be debunked with readily available information. Enter the Information Quality Act.

There are plenty of areas in which public-interest lawyers can seek to make use of the Information Quality Act. One example came to us as the result of the executive orders that established the so-called Muslim ban. In one of the orders, Trump asked the departments of Homeland Security and Justice to create a report studying the risk of terrorism from immigrants.

The report, released in January 2018, claimed that 73 percent of 549 international terrorism defendants prosecuted in federal courts from September 11, 2001, to December 31, 2016, were born outside the United States — a striking data point that appeared to bolster the national security concern that the Muslim ban was ostensibly created to address.

A report from the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security has an information quality standard that might be politely described as equine feces.The problem? The report’s standard of information quality might be politely described as equine feces.

Two coalitions of nongovernmental groups challenged the report under the Information Quality Act: Democracy Forward Foundation and Muslim Advocates filed a lawsuit in California and Protect Democracy, the Brennan Center for Justice, and the Brookings Institution filed a similar complaint in Massachusetts.

The Homeland Security and Justice report provided an ideal test of the Information Quality Act because it is demonstrably flawed and dishonest. As The Intercept noted after the report’s release, the 549 number that government officials used suggested that the Justice Department’s list of international terrorism defendants had been selectively edited to support the Trump administration’s predetermined conclusion.

Since 9/11, the Justice Department has periodically released its list of international terrorism defendants. In March 2010, then-Attorney General Eric Holder presented it to Congress as part of testimony. The list then included 403 defendants. A second version, updated through December 31, 2014, had 580 defendants. A third list ending in 2015 included 627 international terrorism defendants.

Somehow, according to the report from the departments of Homeland Security and Justice under Trump, the list shrunk from 627 international defendants in 2015 to 549 in 2016.

Where did the 78 missing defendants go? Impossible to say, because government officials refused to release the underlying data. And they still won’t — though they’re now struggling to defend the report under the Information Quality Act.

In a December 2018 letter to the Democracy Forward Foundation and Muslim Advocates, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Michael Allen admitted that the report had flaws but that the government can’t “control the way in which information in the report is used or interpreted.” Allen also refused to provide the report’s underlying data, noting that neither law nor policy requires government agencies to make available such work product.

In addition, Allen defended the report’s use of eight “illustrative examples,” which included terrorism defendants whose crimes took place in other countries, but who were brought to the United States only for the purpose of prosecution. With Clintonian wordplay, Allen claimed that “illustrative examples” are not “representative” examples.

“This letter is fascinating, right?” said Robin Thurston, senior counsel for Democracy Forward Foundation, a nonprofit established in 2017 to expose corruption in the executive branch. “It acknowledges a lot of our concerns and walks the line about as close as possible to admitting that the report is false and misleading — and yet they’re letting the report stand.”

Allen sent a similar letter to Protect Democracy, the Brennan Center for Justice, and the Brookings Institution. In the letter, he conceded that “the report could be criticized by some readers,” though he claimed that, despite not providing the underlying data, the Justice Department had been “reasonably transparent.”

The organizations challenging the report are now waiting for a response from the Department of Homeland Security. Once that arrives — and it’s safe to assume that the agency will not volunteer to retract the report — the issue will be on track to go before judges in California and Massachusetts, setting up an unprecedented challenge of Trump administration propaganda under the Information Quality Act.

This should be one of many court challenges. The Trump administration is consistently making dubious claims, bigly, that could be challenged under the Information Quality Act. Officials have said 3,700 people with terrorist ties were apprehended at the border; that a border wall will stop terrorists; and that more than 600 criminals were part of the migrant caravan in November. Democracy Forward Foundation has already challenged as “misleading and unreliable” statements made by Treasury Department officials, including Secretary Steven Mnunchin, in support of the Republicans’ 2017 tax cut.

No more Truth-O-Meters, please. They’re toothless in our Trumpian age. Let’s file some lawsuits and give judges an opportunity to play their constitutional role in our increasingly dysfunctional republic.

The post There’s a Better Battlefield for the War Against Trump’s Lies: the Courts appeared first on The Intercept.

Nos últimos anos, Sergio Moro se tornou o grande herói brasileiro do combate à corrupção. Ganhou prêmios, deu muitas entrevistas, viajou pelo mundo contando seus feitos, enfim, se sentiu muito bem no papel de salvador da pátria. Depois de se dedicar em apressar a prisão do candidato que liderava as pesquisas presidenciais e, consequentemente, pavimentar o caminho para o desfile vitorioso da extrema direita, topou fazer parte do novo governo.

Mas o nosso herói já conhecia o histórico da família Bolsonaro na distribuição de tetas para amigos e parentes no serviço público. Sabia que Jair Bolsonaro encaminhou R$ 200 mil recebidos da JBS para o partido mais investigado pela Lava Jato. Sabia que a Wal do Açaí era uma funcionária fantasma. Sabia que o presidente sonegou e incentivava a população a sonegar impostos. E também sabia da simpatia dele e de seus filhos pelas milícias. Bolsonaro chegou a defender grupos de extermínio da Bahia em plena Câmara dos Deputados. Como diria Jair, basta fazer uma “retrospectiva do passado” para concluir que o juiz topou integrar um governo cujas credenciais éticas do seu líder eram amplamente conhecidas. Moro sabia de tudo.

As notícias desta semana já não deixam mais dúvidas: o presidente tem ligações com as milícias do Rio de Janeiro. Sim, porque não é mais possível descolar as ações do senador Flávio do presidente Jair. Há fatos suficientes para se fazer essa afirmação.

Foi o presidente que apresentou o motorista Queiroz para Flávio, que era apenas uma criança quando seu pai e ele iniciaram uma amizade que já dura mais de quatro décadas. Bolsonaro não explicou o contexto nem apresentou comprovante do empréstimo feito a Queiroz, o homem que conseguiu empregos no gabinete de Flávio para a mulher e ex-esposa do chefe da milícia de Rio das Pedras — o mesmo lugar em que Queiroz ficou escondido antes de ser internado no Albert Einstein. A primeira-dama Michele Bolsonaro está sendo investigada pela Receita Federal por receber um cheque de Queiroz que, segundo Jair Bolsonaro, seria o pagamento do empréstimo feito a ele. O presidente da República é também sócio de Flávio Bolsonaro em uma empresa que o filho omitiu na declaração para o TSE.

Não adianta o presidente dizer que nada tem a ver com as ações do seu “garoto”, que só chegou ao Senado por causa do sobrenome. Trata-se de uma família que cresceu e enriqueceu unida ao longo dos anos na política. Negar isso agora é apenas cinismo. O deputado Eduardo Bolsonaro, por exemplo, é deputado federal, mas tem atuado como um dos porta-vozes do governo federal no exterior. Assim como o vereador Carlos Bolsonaro trabalha com as redes sociais do presidente. Tudo junto e misturado.

Moro largou uma carreira jurídica admirada por boa parte da sociedade para virar um político bolsonarista. Para todo problema ético do governo Bolsonaro, Sergio Moro tem uma resposta hipócrita e constrangedora. Quando Onyx Lorenzoni foi pego duas vezes no caixa 2 — crime que o ex-juiz considerava “pior que corrupção” — Moro aceitou seu pedido desculpas e afirmou que o chefe da Casa Civil goza da sua “confiança pessoal”.

Na semana em que o núcleo bolsonarista aparece envolvido até o osso com as milícias do Rio de Janeiro, o super ministro da Justiça deixou a violência correndo solta no Ceará e viajou com o presidente para Davos. Eu não entendi muito bem o que ele foi fazer em um fórum econômico além de conferir um verniz ético que falta para o governo Bolsonaro, mas, beleza, a explicação até que é razoável. Ele diz que foi apresentar seu trabalho “contra a corrupção, contra o crime organizado, contra o crime violento” e que trabalhar isso no “ambiente de Davos, é bom para os negócios”. Ok. O problema é que no ambiente do Brasil, as ligações da família do presidente com a corrupção, com o crime organizado e violento do Rio de Janeiro estão ficando cada vez mais evidentes.

Nos dias em que esteve em Davos, Moro evitou ao máximo falar das ligações de Flávio Bolsonaro com milicianos. “Não me cabe comentar sobre isso, mas as instituições estão funcionando”. Como não cabe? Não é adequado para um ministro da Justiça comentar o principal escândalo de corrupção do momento do seu país? Não é essa a postura que se espera de um super-herói empenhado em varrer a roubalheira na política. Muitos devotos de Moro devem estar decepcionados.

Os corruptos certamente comemoraram a notícia de que o Banco Central quer excluir parentes de políticos da lista de monitoramento das instituições financeiras e derrubar a exigência de que todas as transações bancárias acima de R$ 10 mil sejam notificadas ao Coaf. Mas Sergio Moro não pareceu chocado com esse retrocesso no combate à corrupção: “Temos de entender melhor por que os reguladores do Banco Central estão propondo essa medida, e aí podemos discutir com eles se é uma boa ideia”.

Moro quer entender melhor os motivos que levaram o banco a querer afrouxar o monitoramento que ajuda a coibir lavagem de dinheiro e desvios de verbas do Estado. A intenção do banco é clara e objetiva, sem espaço para dúvidas, mas Moro ainda precisa pensar se é uma boa ideia. Ele alegou ainda que essa é uma medida do governo anterior, o que não justifica a sua passividade. Esperava-se uma declaração mais firme do atual ministro da Justiça contra o absurdo. As regras que o Banco Central pretende reverter entraram em vigor em 2009, durante o governo Lula, e ajudaram a desvendar muita roubalheira em família, inclusive o laranjal de Flávio Bolsonaro. É inacreditável que o nosso cão de guarda da corrupção esteja titubeando tanto justamente agora.

Brazil’s powerful new justice minister cancelled his press conference at Davos, disappointing an audience keen to hear about key judicial reforms and corruption scandals involving the president’s son. He did find the time to meet with a Brazilian TV star. #iamnotmakingthisup https://t.co/GgbVaz85q1

— Andrew Downie (@adowniebrazil) 24 de janeiro de 2019

Enquanto o ministro da Justiça estava em Davos, outra notícia boa para os corruptos brasileiros: Onyx Lorenzoni e Mourão baixaram um decreto que amplia o número de funcionários públicos que podem decretar sigilo sobre documentos. O ato é um duro ataque contra a Lei de Acesso à Informação, uma importante ferramenta que visa tornar transparente as ações dos governantes e facilitar a fiscalização pela sociedade civil. Agora não são apenas presidente, vice, ministros e embaixadores que podem tornar documentos inacessíveis, como previa decreto de 2012 do governo Dilma, mas funcionários de segundo e terceiro escalão. Segundo apuração do jornalista Breno Costa, agora “mais de 1.200 pessoas no governo federal poderão receber poderes para definir que documentos públicos fiquem em segredo pelo menos até 2034″.

A consequência disso é óbvia: mais documentos se tornarão secretos e haverá menos transparência nas ações do governo. “Transparência acima de tudo. Todos os nossos atos terão que ser abertos ao público”, foi o que prometeu Jair Bolsonaro na primeira semana de governo. Qual será a opinião do nosso ministro da Justiça? Ainda não é conhecida, mas provavelmente ele ainda deve estar pensando se é ou não uma boa ideia.

Sergio Moro se tornou o político que posa para a selfie do Luciano Huck e foge da coletiva de imprensa para não ter que falar sobre a bandalheira da família do seu chefe. Parece que toda aquela volúpia anticorrupção esfriou. A imagem heroica está sendo moída pela realidade. Até agora, Sergio Moro tem se mostrado apenas um soldadinho raso e fiel do bolsonarismo.

The post Sergio Moro virou um soldado raso do bolsonarismo appeared first on The Intercept.

LONDON—Theresa May is clinging on as prime minister, her Brexit withdrawal agreement is floundering, and the European Union is showing no signs of budging. Yup, it’s Crunch Week in Brexit Britain.

But then again, when isn’t it? It was “Crunch Week” when British and EU negotiators raced to sign off on a deal late last year, it was “Crunch Week” when lawmakers in London rebelled against it, and it was “Crunch Week” when May finally presented the agreement to Parliament earlier this month. Oh, and then there was “Hell Week,” “Hell Week 2.0,” and “Bloody Hell Week.” British media have taken to regularly describing the state of the country’s politics as being in “MELTDOWN,” “DISMAY,” and “MAYHEM.” (It is not ideal that the prime minister’s name lends itself so well to the puns the British tabloids are so fond of.)

Indeed, in the two and a half years since Britons made the consequential decision to leave the EU, the process of their departure has been defined by political chaos. In 2017, it was the snap election in which May lost her party’s governing majority after gambling with the hope that she could expand it. The year that followed was one of a near-constant stream of negotiation deadlocks, cabinet resignations, and no-confidence letters. And though 2019 has only just begun, it appears to promise more of the same.

It began with May holding a previously delayed vote on her negotiated Brexit agreement with the EU, which British lawmakers rejected by a record-breaking margin—the kind that, in normal times, would have almost certainly resulted in the prime minister’s resignation.

[Read: Theresa May lives to fight another day. But for what?]

But these aren’t “normal times,” and May isn’t your average prime minister. She survived a vote of no confidence called by the opposition Labour Party against her government, weeks after getting past another vote of no confidence, that one called by her own Conservative colleagues.

That May continues to survive without the governing majority or authority to get her deal through parliament is a testament to how far some of her Brexit deal’s biggest opponents—including the hard-line Brexit supporters within her own Conservative Party and their partners in the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party—will go to stave off a general election. Though they might not like the prime minister’s deal, they like the idea of a Jeremy Corbyn–led Labour government even less.

But it’s also emblematic of just how divided lawmakers remain over how, or even if, Britain’s departure from the EU should happen. The only parliamentary majorities that exist are those who oppose May’s deal (which is the only agreement the EU says it will consider) and those who oppose leaving the EU without a deal altogether (which is the legal default should the U.K. fail to agree to an alternative plan by March 29).

[Read: Brexit is chaos. The movie about it is anything but.]

So what happens next? The truth is that no one, least of all the prime minister, seems to know. After a week of cross-party talks with opposition lawmakers about the government’s next steps, May announced her plan last week: to return to Brussels to seek further concessions. If May’s latest plan sounds familiar, that’s because it is: The prime minister has already appealed to the EU to make changes to the deal, to little avail. The bloc said in a recent statement that it would not agree to changes to the withdrawal agreement.

Lawmakers have spent the past several days debating and adding amendments to May’s proposal, which will go up for a formal vote this week. Should they agree to her plan, then she will return to Brussels (though what she will accomplish there is unclear). If not, other seemingly impossible scenarios will likely be considered, including postponing Britain’s exit date or holding a second referendum. And with them, more crunch weeks will surely follow.

The only realistic certainty is that this won’t be the last crunch week facing Brexit Britain. There won’t be time for many more of them, either.

In a previous item, I included a table of U.S. “top bracket marginal income tax rates” over the past century. This is the tax rate you’d pay on the next dollar of taxable income, whenever you hit the highest tax bracket.

The reason for showing the chart was as a reminder of how significantly tax policy changed about 30 years ago, with the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which was under Ronald Reagan but had bipartisan support. For more than a half-century before that change, the top-bracket rate had always been at least 50 percent, had been as high as 94 percent, and was mostly above 70 percent. Since that change, it’s been in the 30s—now at 37 percent.

The reminder, in turn, was tied to a discussion at Davos this past week, in which a leading tech entrepreneur, Michael Dell, had scoffed at the idea of imposing a 70 percent top-bracket tax rate, asking a questioner to “name one!” country where such rates had coexisted with a strong economy. The “name one” country was the mid-20th-century United States.

Of course, there are a million caveats. In 1986, part of the argument for lowering rates was to reduce the appeal of tax shelters and other loopholes, and broaden the base of income subject to taxes. The fact that the U.S. had sky-high progressive taxes during its decades of post-World War II obviously does not prove that the same rates would make sense now. Correlation is not causation. And so on.

But the historical record is worth being aware of. Now, readers with additional info and reactions.

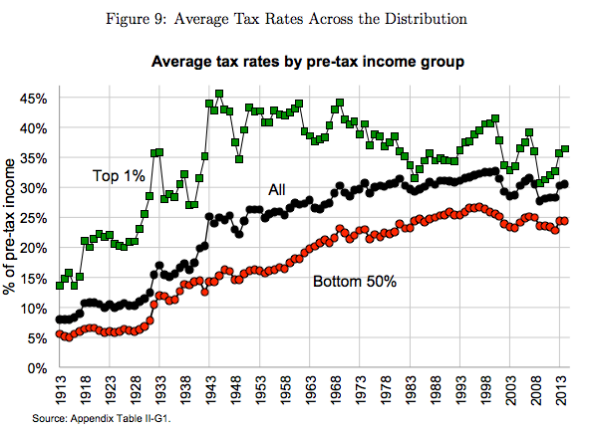

1) What people actually paid. A reader sends this chart, from a 2017 paper by the economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, showing who has borne the effective burden of taxation, over the decades. It’s worth looking at closely.

The chart shows average tax rates—the share of total income actually paid in taxes—rather than marginal rates. The steady increase in average taxes for the bottom 50% is driven mainly by rising payroll taxes.

From Piketty, Saez, and Zucman.

From Piketty, Saez, and Zucman.The reader who sent the chart adds:

Certainly, we may need higher tax rates to pay for essential services. There is much work to be done.

That said, as you likely know, the high marginal tax rates of the past do not align with the relatively static effective tax rate that was actually paid by the wealthy due to exemptions and other changes. It is not that much lower today than it was in the 1950s. Yes, taxes might need to go up, but we shouldn't mislead people into thinking the rich actually paid more in the past.

By any reasonable standard, my family would be considered well-off. Not the 0.01 percent with Bill Gates, but likely in the top 5 percent. We are very fortunate. No, I wouldn't really want to pay higher taxes, but I realize everyone in the upper-middle class on up may need to do so to make a shared investment in our country.

It seems to me the way to truly MAGA would be to invest in the education of children from all backgrounds, work toward a greener future, welcome immigrants who are eager to join our society, and work with other nations to help alleviate human suffering all over the globe.

As a New Yorker, I love that anyone can become one by rooting for the Yankees or the Mets. One day you are from China or Jamaica, the next you are part of the fabric of the city with a shared sense of responsibility and possibility. To me, that's America. I'll climb down off my soapbox now!

2) Taxes as proxy for public investment. Another reader points to an important book on how the U.S. economy worked during its era of post-World War II growth. This is American Amnesia, by Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson. The reader says:

I wanted to point out that it would be useful to consider the work of Yale's Jacob Hacker, who shows that the U.S. economy was the most productive when the top tax rates were what now seems like very high levels. His thesis is that the high rates signified that the levels of government expenditure/investment was also high, which he argues drives overall economic growth. He points out that economic growth performed the best when tax rates were high and unions were strong….

Nuance doesn't seem to work, especially in this day and age, so from a political perspective, if I were advising the democrats, I'd go for the OC pitch that I would slap a high rate on income over $10 million/year. There would be the usual socialist tag bandied around, but I suspect even many republicans would think that once you were raking in $10 million in one year, taxing any amount over that would seem fair.

In their book, Hacker and Pierson write about the change in the Republican party’s attitude toward taxes, starting with the “Contract with America” under which Newt Gingrich won GOP control of the House in the 1994 mid-term elections:

From 1994 on, a simple principle seemed to dictate GOP tax stances: the more a particular tax fell on the wealthiest Americans, the more important it was to cut it. Both Reagan and George H.W. Bush had signaled that a progressive tax code remained a priority and, in 1986 and 1990, had supported tax packages based on that principle. But after the Gingrich revolt, Republicans focused increasingly on tax cuts for the highest income groups—cuts in the estate, dividends, and capital gains taxes, as well as the top marginal income tax rate. They did so even though public opinion polls have indicated consistently that voters’ biggest complaint about the federal tax system is that the rich do not pay their fair share.

3) A different view on “fair share.” On the other hand, from another reader:

Michael Dell was right… It isn't as simple as that, and it is misleading to point back to the earlier decades to make this claim—unless of course if a new 70 percent bracket today would be effectively the same as back then (allowing for all of the loopholes, caps, etc.), but then what's the point of that other than politics?

Of course, if the new 70 percent bracket would not have all of those loopholes, etc. leading to an actual effective tax rate of ~70 percent, then Dell's question would come back - "Show me where that has worked before"...

Related to this topic, it is such as shame when politicians (and others) make the statement like "It's time that they pay their fair share" (referring to the "rich"). We all know that the vast majority of taxes are paid by 15-20 percent of the taxpayers. Fifty percent of the citizens pay $0. It's playing off/creating a "victimhood" mentality, which ultimately is bad for our country (but good for political points in the short term).

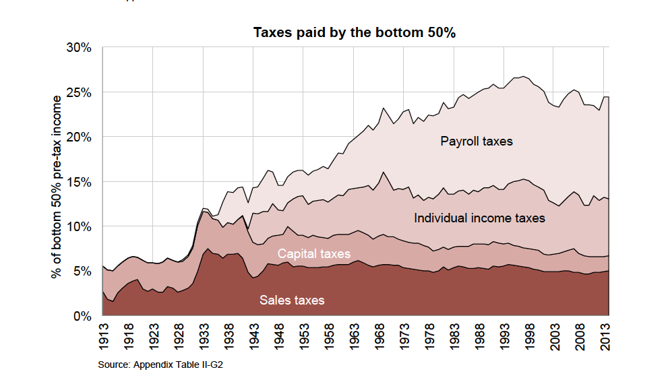

For the record, the “50 percent of the citizens pay $0” claim requires assuming away the largest tax that lower-income households pay, namely the payroll tax. The paper by Piketty, Saez, and Zucman shows that in fact the lower 50% of households pay not $0 but rather about a quarter of their total income in taxes:

Piketty, Saez, and Zucman paper.

Piketty, Saez, and Zucman paper.4) “Very best part of our history.” Finally for today, from another reader, in the Midwest:

Today’s pundits who are raving about the mad socialists (Warren and Ocasio-Cortez) who they claim are trying to destroy our country have never read any economic history, and no doubt would have forgotten if they had actually read about earlier tax policies.

We need more folks to remind us about the time most mature Americans feel was the very best part of our history (post second war) and the reasons for our economic growth and stability during that period.

Earlier this month, Amanda Mull wrote about the ways in which mainstream beauty media promote the idea that “if you find the right product and live the skin-care lifestyle (No alcohol! No dairy! Don’t enjoy anything!), then you will be rewarded with the glow of the youthful and righteous.” In reality, Mull explained, “You can drink as much water and wear as much sunscreen as you want, but the most effective skin-care trick is being rich.”

I work in a retail clothing establishment that also offers skin-care and beauty products. The price range is from almost decent ($30 for a cleanser) to really high end (a $200 face cream). Our customers are mid-40s to 80-plus. Many want “the fix”: take the crow’s feet away, what about sagging jowls, pick up the grooves around the mouth. The search for endless youth is indeed endless, and while we are in the business of providing help, we can’t create miracles or stop the clock. The best I can do, as an honest broker, is to suggest alternatives without making promises that won’t be kept by the product. Some customers appreciate that and understand the limitations of the aging process and what cosmeceuticals can do. But many of our customers will continue to live in a state of denial, and won’t buy unless we/the products “promise” a reversal of the impact of time.

Ms. Mull nails the inherent dilemma of most beauty product customers. It costs money you don’t have to test products enough to find one that works, and meanwhile Instagram posts and magazines provide delusions of grandeur most people won’t achieve. It helps to have honest writers who highlight the issue, and also tie it to larger societal challenges.

Those who are less well-off, unemployed, underemployed, etc., cannot afford healthy places to live—much less healthy food to eat—safe cars to drive, or access to medical care to treat any illness. It can feel like having control over some piece of your life to think that a cream may help you look better, which might lead to a (better) job or some other improvement. We cling to those small things, recognizing that the larger issues are often beyond our control.

Edie Patterson

Richmond, Va.

I was moved and impressed with Amanda Mull’s article on skin care and wealth. I know that she is right; I have aged into my mid-40s only to see the prices of skin care go up depending on what you want to do. Those with means can afford to spend in a single afternoon an amount that would be equivalent to a week’s worth of healthy groceries for a working-class mother of two.

The more important conversation, about our perception of ourselves and the desperate need to appear youthful and wealthy, is highlighted here, and it was refreshing to read.

Carrie Mayo

Baton Rouge, La.

A note of congratulations to Amanda Mull for her darkly observant analysis of women’s skin-care trends and the class disparity thereof—a truly brilliant piece. As a Millennial woman to whom all these products, tips, and tricks are marketed, I loved the irony! Here’s to “the modest goal of looking totally fine.”

Sylvia E. Smith

Denver, Colo.

While this article brings up many good points, the sentence suggesting that most people’s skin will be fine if they eat healthy, exercise, and get enough sleep is highly offensive to the many of us struggling with common but difficult-to-combat skin issues such as cystic acne and psoriasis. I would urge the author to realize the role that genetics plays in “good” skin before writing statements such as that, which serve to only frustrate further those of us who have tried everything from diets to more sleep to cure common skin conditions.

Ashrita Rau

Medford, Mass.

In the year 2514, some future scientist will arrive at the University of Edinburgh (assuming the university still exists), open a wooden box (assuming the box has not been lost), and break apart a set of glass vials in order to grow the 500-year-old dried bacteria inside. This all assumes the entire experiment has not been forgotten, the instructions have not been garbled, and science—or some version of it—still exists in 2514.

By then, the scientists who dreamed up this 500-year experiment—Ralf Möller, a microbiologist at the German Aerospace Center, and his U.K. and American collaborators—will be long dead. They’ll never know the answers to the questions that intrigued them back in 2014, about the longevity of bacteria. Möller’s collaborator at the University of Edinburgh, Charles Cockell, once forgot about a dried petri dish of Chroococcidiopsis for 10 years, only to find the cells were still viable. Scientists have revived bacteria from 118-year-old cans of meat and, more controversially, from amber and salt crystals millions of years old.

All this suggests, says Möller, that “life on our planet is not limited by human standards.” Understanding what that means requires work that goes well beyond the human life span.

Physically, the 500-year experiment consists of 800 simple glass vials containing either Chroococcidiopsis or another bacterium, Bacillus subtilis. The glass vials have been hermetically sealed with a flame. Half are shielded with lead, to protect them from the radiation of radon or cosmic rays, which can cause DNA damage. (A duplicate set of the vials sits in the Natural History Museum in London for backup.) Every other year for the first 24 years, and then every quarter century for the next 475, scientists are supposed to come test the dried bacteria for viability and DNA damage. The first set of data from the experiment was published last month.

[ Read: The quest to kill the superbug that can survive in outer space ]

Opening vials, adding water, and counting colonies that grow from rehydrated bacteria is easy. The hard part is ensuring someone will continue doing this on schedule well into the future. The team left a USB stick with instructions, which Möller realizes is far from adequate, given how quickly digital technology becomes obsolete. They also left a hard copy, on paper. “But think about 500-year-old paper,” he says, how it would yellow and crumble. “Should we carve it in stone? Do we have to carve it in a metal plate?” But what if someone who cannot read the writing comes along and decides to take the metal plate as a cool, shiny relic, as tomb raiders once did when looting ancient tombs?

Glass vials containing dried B. subtilis spores (R. Möller and C. S. Cockell)

Glass vials containing dried B. subtilis spores (R. Möller and C. S. Cockell)No strategy is likely to be completely foolproof 500 years later. So the team asks that researchers at each 25-year time point copy the instructions so that they remain linguistically and technologically up to date.

Möller and his colleagues are among the most ambitious scientists to plan a long-term experiment, but there have been others. In 1927, a physicist named Thomas Parnell poured tar pitch into a funnel and waited for the highly viscous substance to slowly drip down. When Parnell died, custodianship of the pitch-drop experiment passed along a chain of physicists, who dutifully recorded each drop. The last one fell in April 2014, and the experiment can last as long as there is more pitch in the funnel.

[ Read: ‘The pitch dropped’ ]

Plant biology has several long-term studies, too. At a fertilizer magnate’s country estate in England, scientists have been studying how different fertilizers affect the particular crops grown in the same fields year after year since 1843. In Illinois, agricultural scientists have been carrying out a corn-breeding study since 1896. And at Michigan State University, a botanist in 1879 buried 20 glass bottles of 50 seeds to be dug up at regular intervals and tested for viability. The location of the bottles is kept secret to prevent tampering. The last bottle will be dug up in 2020.

Michigan State University also houses an E. coli experiment that could run for centuries. Since February 1988, the lab of the microbiologist Richard Lenski has been watching how E. coli acquire mutations and evolve over the generations. They’re currently on generation 70,500. Because E. coli replicates so quickly, it’s like watching evolution on hyper-speed.

Despite the time-warping nature of this experiment, Lenski didn’t start out thinking about the far-off future. He thought the experiment would run a few years, and at one point, when he felt he had gleaned as much as he could, he considered shuttering it. “But whenever I mentioned to people I might end the experiment,” he recalls, “they said, ‘You can’t.’ That made me realize people were appreciating it for its longevity and for the potential of surprises.” And in 2003, his lab made one of its most surprising findings yet. The E. coli suddenly evolved the ability to eat a molecule called citrate. By looking at previous generations that his lab had frozen and archived, Lenski’s graduate student was able to reconstruct the series of mutations that gradually led to what had looked like a quick switch.

Every day someone in Lenski’s lab transfers the E. coli into a new flask, using the same type of glassware and the same growth media they’ve been using for 30 years. Like the bacteria, the techniques for studying them have evolved—scientists can now sequence E. coli’s entire genome, for instance—and they will keep changing. Lenski has identified a scientist he will bequeath the experiment to when he retires.

“Of course, for an experiment to go on like this, I’m assuming that science still looks somewhat like today, in the sense that universities will exist, there will be professors with labs, and so on,” says Lenski. “Yet if one looks not so far into the past, that isn’t how science was done.” Just a few hundred years ago, money for scientific research came largely from wealthy patrons, not government agencies.

A centuries-long experiment needs a long-term financial plan, too, and Lenski has been looking for a wealthy patron of his own. His experiment has enjoyed government funding, but he knows it’s unreliable, especially if public support for science erodes. Ideally, he’d like to create an endowment, and he’s done the math: A $2.5 million endowment would provide returns of about $100,000 a year, which should cover the costs of materials and the salary of a technician to work on the experiment every day. “So any shout-out for a big donor would be much appreciated,” he wrote at the end of an email to me.

Möller’s 500-year-long microbiology experiment is far cheaper and less involved, as it requires only a researcher to work on it once every 25 years. But it does require people to remember, to value science as an endeavor, and to have the resources to carry it out. Because the experiment began in 2014—before certain world events made everyone realize a collaboration among the U.K., Germany, and the United States perhaps should not be taken for granted—I mentioned to Möller that even planning for a 500-year experiment seems to require a certain optimism about the stability of our current world.

Imagine, he said, the first human who set out exploring: “What is behind the next hill? What is behind the next river? What is behind the next ocean? Our curiosity is always optimistic.” To continue venturing into the unknown is to be continually optimistic.

Before Harry Potter and his friends bewitched my boyhood, I was enchanted by a different set of adventures: those of the teenage sleuths Frank and Joe Hardy, more famously known as the Hardy Boys. And why wouldn’t I be? Their namesake books, which were written by Franklin W. Dixon and debuted in 1927, feature suspenseful titles such as What Happened at Midnight, Footprints Under the Window, and The Haunted Fort, which are brought to life with vibrant cover art and dramatic frontispieces. Within the slight volumes themselves, the young detectives, who are often joined by their friends, solve mysteries in the fictional town of Bayport. As a 7-year-old, I felt the books extended an invitation, a promise: You, too, can save the day.

But as I continued to read the series through middle school and into high school, I began to notice that the beloved franchise’s world—where black characters are a rarity and obviously gay characters are nonexistent—wasn’t much like the one I lived in. Not every book can represent every reader’s personal experience, of course. But beyond the fun exploits, the enduring appeal of the Hardy Boys series, and the reason it has sold more than 70 million copies, stem from its broad relatability. That is, the books take seriously the fact that growing up often means having boundless curiosity, challenging authority, and wrestling with questions of good versus evil.

At the same time, the Americana of the Hardy Boys is lily-white, and various racial stereotypes permeate the series’ earlier volumes. I noticed these more racist elements in the versions I read as a kid—even though my copies reflected the substantial changes made by the books’ packager starting in 1959, partly to address some of the more offensive language and story lines. Yet I still cherish the stories; it’s a thrill for me to revisit the books now, 60 years after their big makeover. Rereading the Hardy Boys series has been an opportunity to untangle my nostalgia around the sleuths, who inadvertently helped me understand my identity through a fictional world not exactly built with boys like me in mind.

Fittingly, the origin of the Hardy Boys franchise was veiled in its own kind of mystery for decades. In particular, there was never a Franklin W. Dixon. That’s the collective pseudonym of the stable of ghostwriters assembled by the publishing tycoon Edward Stratemeyer to crank out Hardy Boys books for his Stratemeyer Syndicate, as his book-packaging empire was called; he expected these writers not to divulge their real identities publicly. (The company also launched other popular children’s series, including Nancy Drew.)

Of the Dixon writers, the most influential is the first one, Leslie McFarlane, who wrote many of the series’ earlier volumes, beginning with the 1927 release and continuing into the ’40s. As the Ohio University journalism professor Marilyn S. Greenwald writes in her 2004 book, The Secret of the Hardy Boys: Leslie McFarlane and the Stratemeyer Syndicate, the indefatigable attachment that many people have to the books arises from McFarlane’s “mastery of narrative” and “the ability of the books to engage the senses, and the quirks that made the characters sympathetic and not wooden.”

[Read: The mystery of the Hardy Boys and the invisible authors]

That world-building is crucial. Take Frank and Joe’s friend, Chet Morton. One of the books’ most memorable characters, Chet has several distinguishing qualities: his skittishness, his where-does-it-all-go appetite, his playfulness, his sensitivity. These quirks—some of which American society tends to view as “effeminate”—offer up a more expansive vision of boyhood, one at odds with the traditional masculine ideal that prizes traits such as athleticism, unfeelingness, hard-nosed machismo, and, generally, being a man’s man (all to the detriment of boys as they grow up). “There was humor, there was friendship,” Greenwald told me in an interview, referring to the affable Chet. And in that way, she added, “there was a very minor subversive aspect to the books.” Think of it like this: While the franchise is named after the Hardys, it’s Chet who gives the books heart—and who gave my scrawny, closeted adolescent self a different boyishness to embrace. For instance, though I couldn’t put my finger on it when I was younger, there was always something delightfully transgressive about the fact that Chet’s car, depicted in the books as the “pride” of his life, is named The Queen. These days, I like to imagine that detail as a winking inside joke with the observant queer reader.

And yet, in part because of the obvious care with which characters such as Chet are presented, as a kid, I was startled by the books’ handling of characters who aren’t white—and who are frequently clumped together using overly broad, loaded terms such as natives and Indians. Consider Volume 12, Footprints Under the Window (one of the books revised in 1965), in which the Hardys and Chet travel to a cluster of fictional islands off the coast of South America to investigate a spy ring. The story, as the teaser page puts it, involves “a cruel dictator” and “a grisly discovery deep in the jungle.” At one point, the boys chase some thieves who’ve stolen a woman’s luggage into the jungle, but they escape. Who are these criminals? “Later, the boys and police officers spoke with the victims of the robbery, a middle-aged American couple named Griffin. Mr. Griffin could not add much to the thieves’ description, except that he judged them to be natives.”

More than merely revealing Mr. Griffin’s views, the line underscores how the book as a whole didn’t bother with defining these native characters beyond stereotypes. Most are never referred to by name in the story, since they serve as scene-setting props to help capture the dangers of the jungle. The next book, The Mark on the Door (revised in 1967), also has its cringeworthy moments as it follows the Hardys to a crime-addled Mexico to look into a cult of largely unnamed “renegade Indians.”

Even these revised books are improvements on the originals in terms of how they portray marginalized groups. For instance, the 1935 version of The Hidden Harbor Mystery has as its archvillain a thickly accented black American man named Luke Jones, who’s the leader of a gang of troublemaking young black men. (A typical line from Jones: “Luke Jones don’t stand for no nonsense from white folks! Ah pays mah fare, an’ Ah puts mah shoes where Ah please.”) The 1961 iteration of the book, for its part, totally jettisons Jones’s character, and the characters who were initially black are made less racially distinct. I remember thinking, when I first learned about these changes as a young adult, that it would have been better to simply give the black characters more dimension than attempt to blot them out. (Notably, the three aforementioned books have such brazen racist stereotyping compared with the other volumes that some critics question whether McFarlane actually wrote them, or whether they were the work of other ghostwriters.)

Still, while the Stratemeyer Syndicate scrubbed up a good chunk of the text when it began its 14-year revision process in 1959—a praiseworthy, intensive task—some of the original subtext lingered, at least for me. More specifically, I still had to contend with the way the books informed how I viewed myself, the kinds of messages I was internalizing. As I got older, snacking on Hardy Boys books increasingly involved a tricky negotiation. On the one hand, there was my enthusiastic identification with the series—with its refreshingly irreverent messaging about boyhood—and on the other, a sense of dis-identification—with its subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle denigration of people beyond the provincial world of the Hardys, who themselves arguably embody the ideals of mid-century white America.

Which isn’t to say that the books ought to be expunged from school libraries or disavowed by educators and parents. After all, the texts do have a lot of redeeming educational value. In addition to illuminating the key beats of a great story—well-defined characters, drama, a compelling narrative arc—they recognize kids’ intelligence, employing elevated language that stretches their vocabulary. (Chet, for instance, always drives a jalopy, a word that was lost on me as a preteen; other advanced words I learned include careening and impetuous.)

The Hardy Boys also offer a critical lesson on the importance of reappraisal—on how, with hindsight, it’s possible to see the cultural blind spots in art. In time, as I read more broadly and deeply, I learned to hold the books up to the light and separate out their derisions and elisions, their racist caricatures and sexist tropes (female characters, such as Laura Hardy, the boys’ mother, are often reduced to overly doting, self-effacing bit players). I still sometimes read the stories today, and even listen to them on audiobook, pulled in by the potency of childhood attachments and the illusion of justice—the knowledge that the Hardys will always bust the baddies—stitched into the stories. But now I approach the books a little bit more as historical documents, at once valuing and rolling my eyes at the parts that haven’t aged quite like I have.

In a sense, the importance of having some critical distance is one of the morals of the franchise. In our interview, Greenwald told me that McFarlane, who died in 1977, cared tremendously about “good-natured mocking” and about getting kids into the habit of questioning things such as authority and power. “The Hardy Boys, in some ways, were smarter than some of the adults,” she said. “The law enforcement, they were bumbling, they couldn’t solve a case, yet the Hardy Boys could.” McFarlane believed in nourishing kids with, as he writes in his autobiography, “a little shot of healthy skepticism.” While people like me may not meaningfully figure into the Hardy Boys’ literary land, I can still appreciate one of their central tenets: that people should never stop scrutinizing the world around them, including as it’s reflected in their books.

In July 2001, at a meeting in Indianapolis, national Democratic chairman Terry McAuliffe told party brethren that gun control was an issue they were wise to avoid. Nobody in the ballroom challenged him. The consensus at the time was that Democrats had lost the House seven years earlier, when Newt Gingrich’s GOP picked up 54 seats, because President Bill Clinton had signed a ban on the sale of assault weapons. And in 2001, many Democrats believed that Al Gore had lost the recent presidential race because southern white males had tagged him as a gun controller.

There was ample evidence that the assault-weapons ban was just one of many factors that fed the Democratic wipeout in 1994, and that Gore’s concern about gun violence (which he rarely voiced) did not trigger his defeat; in fact, he won gun-friendly Michigan and Pennsylvania. But Democrats at the turn of the century lived in terror of the NRA. And McAuliffe, in his speech—which I covered as a political reporter—seemed most concerned that his party was alienating gun owners and cultural conservatives. In his words, “We’ve got to figure this issue out.” That was code for “Let’s not talk about this issue at all.” Which helps to explain why John Kerry, during his 2004 Democratic presidential bid, dressed in duck-hunting garb to convey his respect for the gun ethos and the NRA.

[Read: Gun control is not impossible]

But flash forward to the present day. Democrats have indeed figured the issue out—by morphing from wimps to warriors on gun reform.

Largely overlooked during the government stasis in Washington is the news that House Democrats celebrated their return to power by touting legislation to expand background checks that would cover most firearm purchases—even those made at gun shows and online. The chief sponsor, Representative Mike Thompson of California, was once a recipient of NRA money and a B+ rating from the NRA. But now he’s hailing the gun-reform bill as “a decisive step to help save lives,” with strong support “from public polling to the ballot box.”

The Democrats’ championing of gun reform is not currently a first-tier story, but a new massacre would likely make it so (although the shooting deaths Wednesday of five people in a Florida bank has barely registered). Going forward, there will be a vocal counter-narrative to the ritual Republican “thoughts and prayers,” and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision this week to take a gun case that could expand Second Amendment rights will further fuel the issue. But this time the Democrats, unlike their forebears in the recent past, will not be firing blanks.

[Read: America’s gun-culture problem]

The political winds have decisively shifted. According to the exit polls released last November, 59 percent of the voters in the congressional elections favored “stricter gun-control measures,” with only 37 percent in opposition. Of those who supported more gun control, 76 percent voted for House Democratic candidates. The NRA nevertheless insisted in a postelection statement that “gun control was not a decisive factor on election day,” but it appears that the ever-mounting national casualties—from Sandy Hook to Parkland to the Pittsburgh synagogue, with 116,000 shooting victims annually, 35,000 deaths annually, and historically high gun violence in schools—have undercut the NRA’s power and its purist defense of the Second Amendment.

At ground level, perhaps the strongest electoral evidence was the race for Gingrich’s old district in suburban Atlanta. A Democrat won there for the first time since 1979, and the gun issue was pivotal. Lucy McBath, a self-described “mother with a mission,” entered elective politics to stand up for gun victims, prompted by the shooting death of her teenage son. Meanwhile, in suburban Denver, Jason Crow, a former Army Ranger, ran a gun-reform campaign and knocked off Mike Coffman, an NRA-backed House incumbent. In red Texas, the Democrat Lizzie Fletcher, armed with a long list of gun-reform proposals, toppled John Culberson, an incumbent with an A rating from the NRA. In Arizona, the Democrat Ann Kirkpatrick—who had earned an A rating from the NRA in 2010—won her House race after stumping for tougher background checks and a new assault-weapons ban.

[Elaina Plott: The bullet in my arm]

And in Pennsylvania, four Democratic women won suburban seats after touting gun reform—in districts formerly held by Republican men. Mary Gay Scanlon vowed on her campaign site to “reduce the plague of gun violence,” ranking it as a first-tier issue, with education and health care. Madeleine Dean had previously co-founded a gun-safety group, PA SAFE Caucus, and told the press in December, “Women will bring a different perspective to this [House] conversation. We are mothers, we are grandmothers—that’s what I am first and foremost when I talk about the issue of gun violence.” Susan Wild said during the campaign, “We are living in a country that is like the Wild, Wild West, but with AR-15s. To me, I hesitate to say this, but it’s only a matter of time until gun violence comes to the Lehigh Valley … I’m a huge advocate of sensible gun reform … I’m tired of all the talk, and I want action.” And Chrissy Houlahan has tweeted that she’s “still thinking of the Sandy Hook victims and their families,” and she feels a personal connection. Her cousin Peter was one of the first responders.

The climate change is profound, particularly when one recalls what happened 10 years ago, when President Barack Obama’s attorney general, Eric Holder, called for a restoration of the assault-weapons ban that Congress allowed to expire in 2004. The NRA quickly flexed its muscle, and 65 cowed House Democrats, many from swing districts, formally protested Holder. When Obama’s chief of staff passed the word that Holder should keep his mouth shut about guns, Holder quickly dropped the idea and simply said, “I respect the Second Amendment.”