More than two years after the Larry Nassar scandal rocked Michigan State University, the fallout continues to grow. On Wednesday, President John Engler, appointed a year ago after the scandal first hit, resigned after implying that some of the women whom Nassar assaulted are “enjoying” the “spotlight.” It’s the latest example of how the incident has turned into a full-on catastrophe for the university.

Scientists have long been flummoxed by the majestic rings that surround Saturn, but data from the NASA spacecraft Cassini is providing fresh insight into their existence and origins. Researchers now believe that the rings, which are about half the mass of the Antarctic ice shelf, are leftover shards from a cosmic object that disintegrated in the planet’s vicinity.

The shaving brand Gillette put out a new commercial to mark its 30th anniversary, reflecting on the hypermasculine ideals the company has at times endorsed. While the ad went viral and led to a wave of mixed reactions, Gillette’s decision to release it shows how the brand is trying to tap into social-justice-minded Millennial shoppers who are wary of consumerism and big business.

Evening Reads

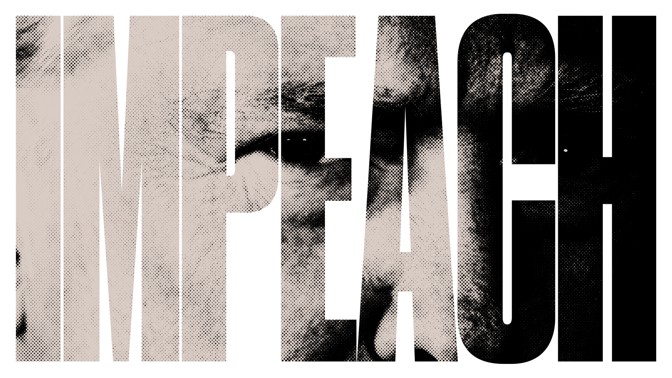

(Benjamin Lowy / Getty / The Atlantic)

In a stunning piece, deeply rooted in history, the Atlantic editor Yoni Appelbaum lays out the nonpartisan argument for impeachment. Why start the process now? “The protections of the process alone are formidable,” he writes. They come in five forms:

The first is that once an impeachment inquiry begins, the president loses control of the public conversation. Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton each discovered this, much to their chagrin.

It isn’t just the coverage that changes. When presidents face the prospect of impeachment, they tend to discover a previously unsuspected capacity for restraint and compromise, at least in public.

Trump is easily the most pugilistic president since Johnson; he’s never going to behave with decorous restraint. But if impeachment proceedings begin, his staff will surely redouble its efforts to curtail his tweeting, his lawyers will counsel silence, and his allies on Capitol Hill will beg for whatever civility he can muster. His ability to sidestep scandal by changing the subject—perhaps his greatest political skill—will diminish.

(Andrew Kelly / Reuters)

Would taxing Americans’ income over $10 million at 70 percent, a discussion kicked off by the freshman representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, discourage entrepreneurship and depress innovation? Derek Thompson argues no:

As John Fernald, an economist at the Federal Reserve, once told me, economists can’t rule out the possibility that productivity has slowed down recently because “we picked all the low-hanging fruit from the information-technology wave.” If capitalist entrepreneurs want to pluck new fruits of innovation, he said, somebody needs to plant new seeds of scientific research.

The U.S. government used to do this well. Fracking, which has made the United States the world’s energy leader, came from federally funded research into drilling technology. The latest surge in cancer drugs came from the War on Cancer, announced in 1971. But the U.S. government doesn’t plant seeds like it used to.

(Sarah Wilkins)

What is it like to visit an existential therapist, who specializes in the weighty issues of the human condition, such as death, meaninglessness, isolation, and freedom? Faith Hill attended a session:

She laughed along with me at some of my more absurd anxieties; she even told me at times that she worried about the same things. At several points, she said, “You might not feel better after I say this,” or “Well, this isn’t comforting, but …” and proceeded to confirm my deepest fears. No, we can’t ever know anyone else’s internal experience. No, there is no objective meaning, and yes, we will all fail at times to create it. Yes, you will die.

Unthinkable

(Samuel Corum / Anadolu Agency / Getty)

Unthinkable is The Atlantic’s catalog of 50 incidents from the first two years of President DonaldTrump’s first term in office, ranked—highly subjectively!—according to both their outlandishness and their importance.

At No. 2: “Very fine people on both sides.”

Join the conversation: Which moments from the Trump presidency would you add to this list? Email us at letters@theatlantic.com with the subject line “Unthinkable,” and include your full name, city, and state. Or tweet using the hashtag #TrumpUnthinkable.

John Crusius of Seattle, Washington State, writes: “Even more important, and even more unthinkable (although not attributable to this presidency), are the facts that virtually no Republican in Congress has challenged this president when any of these 50 events have occurred.”

Ann Ringland, of Durham, North Carolina, writes:“In New Bern, North Carolina, as he was looking at the aftermath of the hurricane, Trump said to a homeowner with a big boat in his front yard, ‘At least you got a nice boat out of the deal.’”

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

It’s a familiar pattern: President Donald Trump’s Republican allies disagree with him on a major issue. They send statements and tweets, and repeat talking points on cable news. But will those in positions of power actually stand up to the president when they are at odds with him?

For Jim Risch, the incoming chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a big test could come if Trump decides to withdraw from NATO, the military alliance with Europe that the U.S. has led for more than 70 years, as he has reportedly suggested he may do.

“There is zero appetite in the United States Congress to leave NATO,” Risch told me on Wednesday. “Fair statement?” he asked, turning to an adviser. “Maybe one voice,” the adviser joked. Risch amended his statement: “Almost zero appetite.”

Coming from a Republican lawmaker who is often portrayed as a steadfast supporter of the president’s, and who is now the most powerful shaper of American foreign policy in the Senate, it was a striking statement. But Risch made clear he wasn't going to get into a public war of words with the president.

“What puts you in a bad place with [Trump] is going out publicly and criticizing him,” Risch told me, “and I don't do that.”

An exit from NATO by the United States, which is by far the largest contributor to the alliance’s military might, was so inconceivable before the Trump era that the NATO treaty actually requires any departing party to give notice to the United States. The alliance has struggled to spread the burden of defense equitably among members and adapt to the post–Cold War world, but an American withdrawal could precipitate the collapse not just of the defense bloc but also of the U.S.-European alliance, inviting Russian aggression in Europe and calling into question the United States’ alliances around the world.

[Read: House Democrats want to investigate Trump’s foreign policy]

Risch’s remarks, which amounted to a subtle drawing of a red line, also stood out because the senator from Idaho repeatedly defended Trump’s approach to Russia during our interview. Amid reports that Trump has concealed conversations with Russian President Vladimir Putin from even his closest advisers, and as Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation continues, Risch said that he does not plan to issue a subpoena to the U.S. government interpreters who attended the president’s meetings with Putin in Germany and Finland, or to hold hearings to shed light on what the U.S. and Russian leaders discussed in those one-on-one sessions, both of which his Democratic counterpart in the House is considering doing.

“The president of the United States, like every president before him, has had private conversations with heads of state,” Risch said, “and people who are authorized to engage in diplomacy … need to have the free hand to be able to conduct it as they see fit … I trust that President Trump did not take every word that Putin said as uttered in good faith.” (Trump has said that he believes Putin’s denial of meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.)

On NATO, Risch didn’t commit to supporting proposed bipartisan legislation, which may be introduced in the new Congress, to prevent the president from ditching the alliance. (In the absence of such a law, which the White House could still fight in court, many legal scholars believe that the president has the authority to withdraw from NATO without consulting Congress.) “I don't want to go there yet,” Risch said, dismissing the prospect of a U.S. exit as mere “talk” and “speculation” at the moment. He (questionably) credited Trump with achieving through rough demands what he and other U.S. officials had long failed to accomplish with polite requests: European NATO members spending more on their own defense. But when I pointed out to Risch that he had once called NATO “the most successful military alliance in the history of the world,” he smiled. “That’s exactly right,” he said.

Risch oversees a 203-year-old committee with jurisdiction over everything from treaties and declarations of war to the president’s diplomatic nominees. And the positions he staked out on NATO and the Trump-Putin meetings are illustrative not just of how he may steer the committee, but also of how he and many other congressional Republicans appear to be compartmentalizing two distinct but interwoven issues: Russia as an adversarial actor abroad and Russia as a political minefield at home.

The senator, for example, described the defining challenge for U.S. foreign policy in the 21st century as fierce competition among the great powers: the United States, China, and Russia. He characterized the Russian government’s interference in the 2016 election as an “enemy-like” action and Russian officials as cheats and liars, urging additional sanctions against Russia for its “horrific acts” everywhere from the Crimean peninsula to the British city of Salisbury. He said the only reason he didn’t join in an unsuccessful revolt this week by Senate Democrats and some Republicans against the Trump administration’s lifting of sanctions against three Russian companies, all partially owned by the sanctioned Russian oligarch and Putin ally Oleg Deripaska, is that he felt the Treasury Department was rightly adhering to the letter of a 2017 sanctions law. A similar effort to challenge the lifting of the sanctions passed with overwhelming bipartisan support in the House of Representatives on Thursday, representing another rebuke to the president, but one that won’t force him to reverse his decision.

[Read: The rise of right-wing foreign policy]

Shortly before I met with Risch, Eliot Engel, the Democratic chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, had told me that Trump’s unceasing praise of Putin despite Russian misbehavior “doesn't quite pass the smell test” and necessitates congressional scrutiny. Yet when I relayed these remarks to Risch, he dismissed them as “political” and said he did not share Engel’s concerns.

As the senator sees it, while Russia has been a bad actor for a long time and must be countered, the investigations into the Kremlin’s interference in U.S. politics and potential collusion with the Trump campaign have caused the president’s political opponents to blow the threat from Putin out of proportion.

“Russia is getting an inordinate amount of attention,” he argued, despite the fact that its meddling in U.S. elections has been “ham-handed” and “China is a much more able competitor” that is challenging the United States “on every front, whether it's economics, whether it's military, whether it's cultural.”

Often, Risch’s stance on Russia has softened upon contact with the president. He has voted for sanctions against Russia and introduced legislation to protect U.S. energy infrastructure from the kind of cyberattack that the Russians perpetrated against Ukraine. But when Trump shared classified information with Russian officials, Risch directed his ire toward the “weasel” and “traitor” who leaked the conversation to the press. He sees no evidence that Russia influenced the outcome of the 2016 U.S. presidential election or colluded with the Trump campaign. In the wake of Trump’s murky meeting with Putin in Helsinki last summer, Risch’s predecessor as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the Tennessee Republican Bob Corker, angrily summoned Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to a hearing to explain what Trump and Putin had agreed to. Risch, however, didn’t ask about the summit once during the hearing, instead praising the administration for its approach to NATO and Iran.

“The fortunes of the United States depend on [Trump] being successful,” Risch told me. “I want to do everything I can to make him successful. I don't work for him. I work with him.”

Corker might have believed that his public critiques would set Trump on a successful path, but Risch claims there’s a more effective way to get through to the commander in chief.

“I disagree with [Trump] from time to time. When I do, we talk about it, but I don't do it on the front page of the paper,” he continued, comparing his approach to him and his wife not arguing in front of their kids.

[Read: Trump wants little to do with his own foreign policy]

Asked whether Corker’s retirement and the passing of John McCain, another prominent critic of the president’s, had removed Republican constraints on Trump’s foreign policy in Congress, Risch rejected the premise of the question.

“The president's already constrained by his constitutional limits and the legislative branch is constrained by its constitutional limits,” he told me. “That is wishful thinking by national media that want somebody to stand up and punch the president in the nose … That is not my role.” (Of course, there is a middle ground between pulling your punches and punching the president in the nose, such as conducting oversight of the administration’s statecraft, which Risch promised to “take seriously.”)

A 75-year-old former trial lawyer, state senator, and governor in Idaho, Risch entered Congress in 2009 and boned up on foreign policy by serving on the Senate Intelligence and Foreign Relations Committees. He endorsed Marco Rubio during the Republican presidential primary in 2015 and ultimately voted for Trump even though he said that doing so was “distasteful.” While he seems sympathetic to aspects of the president’s “America first” agenda, he doesn’t come across as a Trumpian nationalist. Nor, however, does he appear to be an internationalist in the mold of Rubio. On the whole, he evinces a somewhat parochial outlook on the world, driven by national and local interests.

In discussing the issues he will focus on in his chairmanship, for instance, he has highlighted Idaho-centric concerns such as a Chinese company’s alleged theft of trade secrets from a Boise-based memory chipmaker and the renegotiation of the Columbia River Treaty with Canada. He’s said that he won’t need to travel much in the role because so many foreign dignitaries pass through Washington, D.C.

Risch said that his first order of business, aside from working on confirming the administration’s diplomatic appointees, is to hold a hearing in February on the “challenges to [America’s] standing in the world.” Corker accused Trump of wrecking that standing by deliberately “breaking down relationships we have around the world that have been useful to our nation.”

But if Risch feels the same way, he didn’t say it.

Subscribe to Radio Atlantic: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Play

On this week’s show, Alex Wagner chats with Atlantic staff writer Franklin Foer about the startling news of an FBI investigation that asked if President Trump was secretly working on behalf of Russia.

Frank and Alex debate how exactly to explain President Trump’s relationship with Vladimir Putin: handler and asset or mere man-crush?

The news of the week didn’t stop there though. In the following days, it emerged that Trump has gone to “extraordinary lengths” to conceal details of his conversations with Vladimir Putin and that he’d even discussed withdrawing the United States from NATO.

Listen in for how to weather what feels like the documentary remake of The Manchurian Candidate. Is the president working for a foreign power? Can one connect the dots without leaving the walls covered in pushpins and red thread?

VoicesAlex Wagner (@AlexWagner)

Franklin Foer (@FranklinFoer)

It’s Thursday, January 17. The partial government shutdown is now in its 27th day.

‘Zero-Tolerance’ Policy: Donald Trump’s administration likely separated thousands more children from their parents than previously thought since the practice of family separations first spiked in 2017, a new inspector general report finds. While administration officials had once denied that a family separation policy was ever official, it was revealed in 2018 that more than 2,000 children had been separated from their parents and placed in custody elsewhere, sometimes in facilities thousands of miles away from the border.

Tit for Tat: After House Speaker Nancy Pelosi disinvited Trump from delivering the State of the Union, the president retaliated today by canceling Pelosi’s planned congressional delegation trip to Brussels, Egypt, and Afghanistan. With tempers on both sides running high, the shutdown now seems even further from a resolution, reports Russell Berman.

Shutdown Watch: The federal-government shutdown is deeply unpopular among voters, but Trump and GOP senators don’t seem to care—they’ve grown used to representing only a minority of Americans, writes Ronald Brownstein.

Beto Watch: Beto O’Rourke hasn’t said if he’s running for president, but some Democratic operatives are building a campaign for him anyway.

—Madeleine Carlisle and Olivia Paschal

Ideas From The Atlantic

(Benjamin Lowy / Getty / The Atlantic)

Impeach Donald Trump (Yoni Appelbaum)

“The United States has grown wary of impeachment. The history of its application is widely misunderstood, leading Americans to mistake it for a dangerous threat to the constitutional order. That is precisely backwards. It is absurd to suggest that the Constitution would delineate a mechanism too potent to ever actually be employed.” → Read on.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Has the Better Tax Argument (Derek Thompson)

“When Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez suggested this month that the United States should tax income over $10 million by 70 percent, it galvanized something unusual: a broad and substantive national conversation about the design and purpose of federal tax policy. No, I’m just kidding. It kicked off a lot of screaming about socialism, especially on cable news.” → Read on.

Barr May Do Exactly What Trump Wants (Adam Serwer)

“Taken as a whole, Barr’s testimony is less comforting than it seemed. Barr is a respected party elder who possesses the legitimacy, legal acumen, and ideological convictions to shield the president and undermine the rule of law without committing the sort of ham-handed errors that could turn the public or Congress further against Trump.” → Read on.

(Samuel Corum / Anadolu Agency / Getty)

Unthinkable is The Atlantic’s catalog of 50 incidents from the first two years of President Trump’s first term in office, ranked—highly subjectively!—according to both their outlandishness and their importance.

At No. 2: “Very fine people, on both sides.”

Join the conversation: Which moments from the Trump presidency would you add to this list? Email us at letters@theatlantic.com with the subject line “Unthinkable,” and include your full name, city, and state. Or tweet using the hashtag #TrumpUnthinkable.

Readers told us:

“My specific addition would be his accusation that Obama bugged him late in 2016.”

—Scott Brown, Carmel Valley, California

“The list doesn’t address candidate Trump … but in some ways that list is even more worrying, because it demonstrates just how ugly the mood in our country has become.”

—Steven Coleman, Townsend, Massachusetts

A federal worker collects a free bag of groceries from Kraft Foods on the 27th day of the partial government shutdown in Washington, D.C. (Joshua Roberts / Reuters)

What Else We’re Reading◆ Is Trump Trying to Politicize Agriculture Data? Some Former USDA Officials Suspect Yes. (Christie Aschwanden, FiveThirtyEight)

◆ Why Bill de Blasio Is Acting Like a 2020 Candidate (David Freedlander, New York)

◆ If We Forget Appalachia’s Radical History, We Will Misunderstand Its Future (Kim Kelly, Pacific Standard)

◆ State Department Calling Employees Back to Work During the Shutdown (Nahal Toosi, Politico)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily, and will be testing some formats throughout the new year. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

She disinvited him from delivering the State of the Union during a government shutdown. He grounded her plane, abruptly canceling her taxpayer-funded trip to a foreign war zone.

Two weeks in, the relationship between the new House speaker, Nancy Pelosi, and President Donald Trump is off to a smashing start.

Forget a swift resolution to the record-breaking shutdown: As hundreds of thousands of federal employees continue to work without pay, the two most powerful elected leaders in the country are locked in a duel of personal vengeance, making the possibility of good-faith negotiations to end the impasse even more unlikely.

On Thursday, Pelosi suggested that Trump delay his annual speech to Congress, essentially threatening to use her power as speaker to block him from the Capitol. (The State of the Union is delivered by formal invitation from lawmakers.) In response, the president was initially, and uncharacteristically, silent. No name-calling tweets, no blustery sound bites. But on Thursday afternoon, just as Pelosi was about to board a plane bound for Europe, Trump exacted his revenge.

The president fired off an icy-toned letter to Pelosi informing her that he’s postponing her week-long visit to Brussels, Egypt, and Afghanistan—Pelosi’s first congressional-delegation trip during her second stint as speaker. “We will reschedule this seven-day excursion when the Shutdown is over,” the president wrote dismissively. “In light of the 800,000 great American workers not receiving pay, I am sure you would agree that postponing this public relations event is totally appropriate.”

[Read: Nancy Pelosi’s power move on the State of the Union]

Overseas travel to U.S. military bases, whether by the president or by members of Congress, is usually a closely guarded secret because of security concerns until the participants have landed safely at their destination. For that reason, Pelosi’s planned trip abroad—known colloquially inside the Capitol as a “co-del”—had not been publicly announced until White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders sent Trump’s letter to reporters.

Congressional operations are unaffected by the partial government shutdown because the appropriations bill funding the legislative branch was one of the few that had already been enacted for 2019. But because the military operates the trips that send members of Congress abroad, Trump has the authority to cancel them. “We approve all these congressional trips that use government or military planes,” a White House official told Roll Call.

The president’s decision, however, upended the lawmakers’ plans at the last possible moment. The House adjourned for the week on Thursday afternoon, and an Air Force bus carrying the members to the airport had already left the Capitol. Reporters spotted the bus, with the lawmakers still aboard, returning shortly after Trump’s letter went out.

Sanders told reporters that all congressional-delegation trips would be postponed during the shutdown—a decision that affects Republican lawmakers as well as Democrats, since most overseas travel is bipartisan. The Pelosi spokesman Drew Hammill said the speaker’s primary destination was Afghanistan, with a stop for pilot rest in Brussels, where she planned to “affirm the United States’ ironclad commitment to the NATO alliance.” The itinerary did not include a stop in Egypt, as Trump’s letter claimed.

“The purpose of the trip was to express appreciation and thanks to our men and women in uniform for their service and dedication, and to obtain critical national security and intelligence briefings from those on the front lines,” Hammill said in a statement.

The presidential retaliation drew a quick and surprising rebuke from a Trump ally who makes frequent official trips abroad, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina. “One sophomoric response does not deserve another,” he tweeted. “Speaker Pelosi’s threat to cancel the State of the Union is very irresponsible and blatantly political. President Trump denying Speaker Pelosi military travel to visit our troops in Afghanistan, our allies in Egypt and NATO is also inappropriate.”

As I wrote on Wednesday, the language in Pelosi’s letter was formal and polite, giving it the veneer of typical government communications. In his own letter, Trump never referenced the State of the Union address, but his sarcastic tone made little effort to hide his contempt. Trump belittled Pelosi’s planned trip as an “excursion” and “a public relations event,” and he suggested the optics of an overseas visit would be negative in the middle of a shutdown. The president, however, took his own taxpayer-funded trip to visit troops in Afghanistan over Christmas, after the shutdown had already begun. And senior administration officials, including Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, are still scheduled to attend the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, next week.

Trump suggested Pelosi’s time would be better spent negotiating with him in Washington, but so far their talks have been unproductive: The president continues to demand billions in funding for his border wall, and the speaker refuses to discuss funding while the government remains closed. If their tit for tat over the past two days is any indication, the president and the speaker remain worlds apart, and the 27-day government shutdown remains far from over.

Updated at 5:28 p.m. ET on January 17, 2019.

There’s a Gatorade button attached to my basement fridge. If I push it, two days later a crate of the sports drink shows up at my door, thanks to Amazon. When these “Dash buttons” were first rumored in 2015, they seemed like a joke. Press a button to one-click detergent or energy bars? What even?, my colleague Adrienne LaFrance reasonably inquired.

They weren’t a joke. Soon enough, Amazon was selling the buttons for a modest fee, the value of which would be applied to your first purchase. There were Dash buttons for Tide and Gatorade, Fiji Water and Lärabars, Trojan condoms and Kraft Mac & Cheese.

The whole affair always felt unsettling. When the buttons launched, I called the Dash experience Lovecraftian, the invisible miasma of commerce slipping its vapor all around your home. But last week, a German court went further, ruling the buttons illegal because they fail to give consumers sufficient information about the products they order when pressing them, or the price they will pay after having done so. (You set up a Dash button on Amazon’s app, selecting a product from a list; like other goods on the e-commerce giant’s website, the price can change over time.) Amazon, which is also under general antitrust investigation in Germany, disputes the ruling.

Given that Amazon controls about half of the U.S. online-retail market and takes in about 5 percent of the nation’s total retail spending, it’s encouraging to see pushback against the company’s hold on the market. But Dash buttons are hardly the problem. Amazon made online shopping feel safe and comfortable, at least mechanically, where once the risk of being scammed by bad actors felt huge. But now online shopping is muddy and suspicious in a different way—you never really know what you’re buying, or when it will arrive, or why it costs what it does, or even what options might be available to purchase. The problem isn’t the Dash button, but the way online shopping works in general, especially at the Everything Store.

“They sent the wrong tea lights,” my wife announced recently, after tearing open the cardboard box Amazon had just delivered. “It’s the wrong brand, and 50-count instead of 75.” This is not so unusual, actually. Amazon moves a huge volume of goods, and its warehouse workers are poorly treated humans, not just robots. Errors are bound to happen occasionally.

On top of that, Amazon is more than willing to fix its errors. In most cases, you can return an item for a refund or exchange with a few button presses on the website or in the app. And when Amazon messes up, as in the case of our tea lights, the company usually offers free return shipping, and even free UPS pickup, so you don’t even have to leave the house to rectify the error. These are some of the reasons Amazon consistently ranks high in customer-service satisfaction: The company appears to give people what they want, including correcting problems when they arise.

But a customer-service orientation masks how Amazon has changed consumer expectations and standards as they relate to retail purchases. At BuzzFeed News last year, Katie Notopoulos wrote about how terrible Amazon’s website is, prompted by its offering her a subscription deal for bassoon straps (a product Notopoulos reported needing to replace once every two decades or so), and a warranty for bottle brushes (which cost $6.99).

Notopoulos’s examples just scratch the surface of all the possible confusions that can arise when shopping on Amazon: Products are offered for “Prime” delivery, which is supposed to mean two-day shipping. But sometimes Prime means four days or longer. In other cases, one color of a given product—neoprene AirPods-case cozies, for example, which I recently purchased—might be available via Prime, but another might not.

[Read: How to lose tens of thousands of dollars on Amazon]

Even determining what’s available to purchase, via a keyword search on Google or Amazon, produces confusion far broader and deeper than the price fluctuations obscured by a Dash button. I recently tried to search for a heat-pump-compatible thermostat on the site. I got a litany of results, all thermostats for sure, but it was difficult to figure out which ones really worked with a heat pump. Eventually I gave up and resolved to visit Home Depot, which I still haven’t done. Another time, I tried to look for a 5-by-8-inch picture-frame mat on Amazon. But every other possible combination of mat came up instead: 8-by-10, 5-by-7, 8-by-8, 5-by-5. A hedge-trimmer battery I purchased came with a charger, but I didn’t realize it from the product description, so I ordered a duplicate charger as well—that charger arrived first, for some reason, and I had opened the packaging so couldn’t return it.

Apparel and other items with many options are particularly confusing. Determining if Amazon has the color-and-size combination you’re after for a particular dress or pair of sneakers can be disillusioning—as I write this, for example, Adidas Samba shoes are available for $72.95 in a men’s size 9 without Prime shipping, but for $57.58 in a size 12 with Prime two-day delivery. And because different configurations might ship from different sellers warehoused in different places, the chances of getting something different than you thought you ordered is high. As my colleague Alana Semuels has reported, Amazon is an aggregator of goods from various sources, which makes counterfeit products more common in some cases. In others, it can be hard to discern that some items sold by third parties on Amazon Marketplace, such as electronics or watches, are “gray market” products—authentic, but sold without domestic warranties or support. Cheap goods from China also proliferate on Amazon, some of which can be dangerous or duplicitous, from exploding USB chargers to perfume laced with urine or antifreeze.

It’s a far cry from Amazon’s beginnings as a retailer of books—“among the world’s most reliable, durable units,” as my colleague Derek Thompson recently put it. There’s no ambiguity about what you’re getting when you buy a particular book, CD, or DVD. But as the retailer expanded into the Everything Store it has become, it also changed consumers’ expectations about the experience of shopping.

[Read: I delivered packages for Amazon and it was a nightmare]

That brings us to Germany’s Dash-button ban: It’s difficult to know exactly what the product costs when you press the button to order it. Prices on Amazon sway up and down in mysterious ways, driven by computational pricing models that consumers can never see or understand. If configured to do so, pressing the Dash button can send a notification to the account holder’s smartphone, which can be followed to confirm pricing and cancel the order if desired. From the perspective of German law, this isn’t enough; the default behavior is for the purchase to complete, absent sufficient information.

But consumer-protection laws like the one in question only eke out marginal victories against the broader retail situation that Amazon inaugurated. The products available to purchase in the first place still feel arbitrary, as do their changing prices, their seemingly inconsistent availability and shipping times, the reliability of their arrival (thanks in part to Amazon Flex, the company’s gig-economy delivery service), and not to mention whether you actually get the product you ordered.

Amazon doesn’t necessarily agree that it has altered online commerce so significantly. “There is an important difference between horizontal breadth and vertical depth,” an Amazon spokesperson told me. “We operate in a diverse range of businesses, from retail and entertainment to consumer electronics and technology services, and we have intense and well-established competition in each of these areas. Retail is our largest business and we represent less than one percent of global retail and around four percent of U.S. retail.”

But there’s a reason that we used to have shoe stores, hardware stores, grocery stores, bookstores, and all the rest: Those specialized retail spaces allow products, and the people with knowledge about them, to engage in specialized ways of finding, choosing, and purchasing them. On Amazon, everything gets treated the same. The problem with an Everything Store is that there’s no way to organize everything effectively. The result is basically a giant digital flea market. Amazon is so big, and so heterogenous, that the whole shopping experience is saturated with caprice and uncertainty. It’s not that Dash purchases alone might produce a result different from the one the buyer intended, but that every purchase might do so.

Saturn has confounded scientists since Galileo, who found that the planet was “not alone,” as he put it. “I do not know what to say in a case so surprising, so unlooked-for, and so novel,” he wrote. He didn’t realize it then, but he had seen the planet’s rings, a cosmic garland of icy material.

From Earth, the rings look solid, but up close, they are translucent bands made of countless particles, mostly ice, some rock. Some are no larger than a grain of sugar, others as enormous as mountains. Around and around they go, held in place by a delicate balance between Saturn’s gravity and their orbiting speed, which pulls them out toward space.

Scientists got their best look at the planet nearly 400 years after Galileo’s discovery, using a NASA spacecraft called Cassini. Cassini spent 13 years looping around Saturn until, in September 2017, it ran out of fuel and engineers deliberately plunged it into the planet, destroying it. More than a year later, scientists are still sorting through the data from its final moments, hoping to extract answers to the many questions that remain about Saturn.

[Read: This is the way Cassini ends]

The latest findings, published Thursday in a study in Science, answer a fundamental but surprisingly evasive question: How much stuff is actually in those stunning rings? Estimates of the mass of the rings have varied wildly for decades, starting with the twin Voyager spacecraft, which whizzed by Saturn in the late 1970s and early 1980s on their way through the solar system. Even Cassini, nestled inside Saturn’s orbit, couldn’t provide accurate measurements until the very end.

For most of its life, Cassini’s orbit was outside both Saturn and its rings. “You got a combined mass of Saturn plus the rings, and there was really no way to separate it out,” says Linda Spilker, the lead scientist for the Cassini mission, who was not involved in the latest research. “Here was our first chance.”

In its last maneuvers, Cassini wove in and out of Saturn’s rings. The spacecraft was jostled by the gravity of the bands, as well as powerful winds emanating from deep within the planet’s atmosphere. Scientists used the data produced by these effects to calculate the mass of the rings. They say that the mass is about 40 percent that of Mimas, a moon of Saturn, which is about 2,000 times as small as Earth’s moon.

[Read: Microbes could thrive on Saturn’s icy moon.]

In more earthly terms, the rings are about half the mass of the entire Antarctic ice shelf, spread across a surface area 80 times that of Earth.

“It is the most accurate measurement of the rings of Saturn,” says Bonnie Buratti, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who worked on the Cassini mission but who was not involved in the study. “The error margins are kind of pretty big—there’s about a 25 percent, almost 30 percent uncertainty—but it’s way more accurate than anything we’ve had before.”

The new estimate helps to answer another Saturnian question that has puzzled scientists: How old are the rings? For decades, the scientific community was split into two camps. One believed that the ring system formed when Saturn did, 4.6 billion years ago, when the solar system as we know it emerged from swirling clouds of dust left over from the fiery birth of the sun. The other suggested the rings were a youthful feature, formed only 100 million years ago, when dinosaurs walked the Earth.

The latest research bolsters the case for a more recent origin. According to current models, the more massive the rings, the older they must be, and vice versa. The new study suggests that the rings are less massive than scientists suspected, which means they’re also younger. The study authors say their new estimate, combined with previous research, suggests the rings are 10 million to 100 million years old.

There’s plenty of wiggle room in that range. Other analyses focused on the margins of error in Cassini data suggest that parts of the ring system may be as old as 1.5 billion years.

Still, most scientists now agree that the rings did not form alongside Saturn. This leads us to yet another unresolved question: Where did the rings come from? A primordial origin story would have been a very convenient one: The young solar system was a chaotic mess of flying debris, and it would have been possible for Saturn to lasso some of it into a lasting orbit.

Scientists now suspect the rings are the fragmented bits of a cosmic interloper. A moon, a comet, or an asteroid must have strayed too close to the planet. Trapped between two gravitational forces—one tugging it toward Saturn, and the other drawing it away—the object broke into shards. Over time, the pieces flattened out into a delicate disk. “It’s like a graveyard spread around the planet,” says James O’Donoghue, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who studies the Saturn system.

[Read: A new way to measure how fast the universe is expanding]

To truly probe the rings’ origins, scientists could use another Cassini. “If money was of no object—and it is a big object—you could send a probe over there and excavate a bit of the rings,” O’Donoghue said. “You could pick up the boulders and look inside them and really narrow down the composition.”

The youthfulness of the rings raises yet another question, Spilker said. “Were there other ring systems, perhaps that were older and then just, over time, slowly disappeared?” she said. If that’s right, the one we see now could be only the latest in a series of ring systems, the most recent victim of Saturn’s massive pull.

As majestic and eternal as they seem now, Saturn’s rings are constantly shedding material. Sunlight and other cosmic effects can transform idle, icy debris into electrically charged particles. In their new state, the particles are less able to resist the tug of Saturn’s gravity and become swept into its atmosphere, where they vaporize, “raining” water onto the planet. According to O’Donoghue’s research, this process dumps as much as 4,400 pounds of water onto Saturn every second. He predicts the rings will vanish in 300 million years.

If the thought of Saturn losing its trademark feature is disappointing, consider that there are others out there. Not just Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune, which have very thin rings of their own, though they pale in comparison to the grandeur of Saturn’s. If there’s one thing that the study of exoplanets—planets beyond our solar system—has taught us, it’s that our planets aren’t special. Buratti is convinced that someday, with telescope technology powerful enough, we’ll make out the curves of the rings around a distant planet, in another solar system. There are other Earths, other Jupiters, other Neptunes, a cornucopia of rocky and gaseous planets coasting through the cosmos. Surely there must be other Saturns, too.

How could you market something that wasn’t real? That’s the question Brett Kincaid, a commercial director who helped promote the infamous Fyre Festival, is forced to confront in a new Netflix documentary out Friday. Titled Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened, Chris Smith’s film is a fairly straightforward accounting of the failed event that triggered a maelstrom of social-media schadenfreude in 2017, when hundreds of attendees were lured to a Bahamian island for a luxury getaway that promised major musical acts, ritzy accommodations, gourmet food, and Instagram celebrities in the middle of paradise.

What visitors got instead was an empty corner of an island littered with disaster-relief tents that had been drenched in a prior storm. There was no other housing, no staff, barely any food, no way to immediately depart, and, of course, no music or celebrities. In Fyre, Kincaid offers a defense of himself and other contractors hired by the festival co-organizer Billy McFarland, who is now serving a six-year prison term for wire fraud. “Everything was real,” Kincaid insists in the documentary. “Everything looked real. If you get hired to do a BMW commercial and that BMW then has a faulty engine, how the fuck can you possibly know whether or not they’re going to do good on what they said they were gonna do?”

Kincaid is trying to explain how he and celebrities like Bella Hadid and Emily Ratajkowski, who promoted the doomed festival, became part of the initial publicity wave that McFarland devised to attract ticket-buyers. The experience featured in those commercials, which showed beautiful people frolicking on a beach, was a fantasy, pure and simple. In the documentary, Fyre employees acknowledge that the shooting of the promos, which happened over a joyful weekend in the Bahamas, was the closest anyone came to actually enjoying the extravaganza McFarland had advertised.

Smith is a documentarian who specializes in using the story of an intriguing person as a lens to examine some wider cultural phenomenon. His American Movie is a wonderful portrait of outsider art; Collapse is a thrilling exploration of the blurry line between radical thought and full-on paranoia; and Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond dug into Jim Carrey’s warped experience with method acting on the set of Man on the Moon. Fyre is primarily a journalistic exhumation of the Fyre Festival’s ridiculous excesses. But via interviews with both dissatisfied ticket-buyers and nervy ex-employees, the movie also scrapes away the sheen of the flamboyant “influencer” lifestyle that McFarland leveraged to sell tickets and hook investors.

A rival documentary titled Fyre Fraud, released on Hulu days before Fyre was set to land on Netflix, makes that theme more prominent. While Smith’s film is more focused on McFarland’s management of the festival, the Hulu doc (directed by Jenner Furst and Julia Willoughby Nason) is more bluntly polemical, digging into “influencer culture” as a broader societal symptom that McFarland exploited when marketing the festival. Fyre Fraud leans on montages and step-by-step explanations of how Instagram celebrities monetize their sponsored posts and how easily McFarland could use that network to create an event he had no qualifications to run. The Hulu film also has a strange animus toward Millennials and is fond of using pop-culture clips to explain simple concepts (Billions helps to define what a U.S. attorney is, while Family Guy outlines how a high-interest loan works).

[Read: Rising Instagram stars are posting fake sponsored content]

Fyre Fraud also features an awkward interview with McFarland that documentary producers paid for—somewhat deflating the movie’s invective against celebrities who translate their fame into promotional dollars, since the film arguably empowered McFarland to do exactly that. McFarland, who was not interviewed for Fyre (Smith said letting the organizer make money off the project would have felt “wrong”), is an undeniably compelling figure, a next-level scam artist who seems convinced that he can talk his way out of any accusation. But his involvement gives the Hulu documentary a particularly icky edge. The Netflix movie, in turn, was made in partnership with Jerry Media, which was also involved in the festival, and the Hulu film is much tougher on the company (for its part, Netflix has stated that Jerry Media never requested favorable coverage).

In general, Smith lets McFarland’s employees and contractors tell their side of the story, and almost all of them sound like people who recently came out of hypnosis. So many anecdotes revolve around them informing McFarland that some basic goal for staging the festival—like arranging housing, or travel, or food—was going to be impossible to pull off in such a short time. McFarland would invariably either ignore the news or convince workers that there was a positive spin to be put on it. He’d occasionally leave the office and somehow return with millions more dollars made from hoodwinking investors.

The story of the Fyre Festival is certainly one of perverse fascination. When it unfolded on Twitter, part of the thrill for observers was imagining the horror of people who had paid thousands of dollars for tickets and showed up to a windswept, mostly empty beach that they couldn’t escape. But Fyre is also a tale about how the delights promised by social media—think of those sun-kissed models running on the beach—are ephemeral and often illusory.

After the festival’s collapse, Fyre depicts McFarland’s next move with shocking, exclusive footage: The organizer holed up in a fancy penthouse with his friends, pondered how to capitalize on his failure, and then sold VIP tickets to events like the Grammys. McFarland made at least another $100,000 doing that (largely by exploiting the Fyre mailing list) before being sent to jail. Even in his seemingly lowest moment, McFarland went back to the same imaginary well of a glamorous lifestyle that anyone could have for the right price. He was hawking something that wasn’t real, and people kept buying into it.

John Engler was supposed to be a safe choice. He was a former Michigan governor and an alum of Michigan State University, and last January he was brought in to replace Lou Anna K. Simon, who had resigned following the Larry Nassar scandal. He was a Republican, and his board-appointed senior adviser was a Democrat; the board thought that would quell fears of overt partisanship. On Wednesday, Engler, not yet 365 days on the job, tendered his resignation.

The board was initially happy with its choice in Engler; the students and survivors of sexual abuse by Larry Nassar, who pleaded guilty to criminal misconduct for molesting seven girls and was accused of assaulting more than 150 people, were not. Engler himself had been accused of failing to respond to allegations of sexual assault at a women’s prison while he was governor. “To choose someone like John Engler, it tells us that they’re learning nothing from what’s going on,” Natalie Rogers, a student and co-founder of #ReclaimMSU, told The Atlantic at the time.

[Read: The moral catastrophe at Michigan State]

A full year had not lapsed before the board was at Engler’s throat. In April, Kaylee Lorincz, who was sexually assaulted by Nassar, said that Engler offered her $250,000 to drop her lawsuit against the university. One of his senior advisers called the accusation “fake news.” In June, emails revealed that Engler accused Rachael Denhollander, the first gymnast to accuse Nassar, of getting a “kickback” for helping lawyers “manipulate” other gymnasts into coming forward. Eight days after the initial report, Engler apologized. Then, in an interview with The Detroit News this month, he suggested that some Nassar survivors might be “enjoying” the “spotlight.” Finally it was one comment too many. Survivors, students, and advocates fumed. The board, which had been fielding calls for his removal since he was appointed, called an emergency session. Individual board members voiced their frustration.

He offered his resignation before the board had a chance to fire him. In an 11-page letter sent Wednesday night, Engler laid out his case for how his tenure had made Michigan State a better place. “I sought to move with urgency and determination to initiate cultural change at MSU,” he wrote. This was a job, he added, that he did not want, but which he accepted to help a university that he loved as it faced a crisis. There were now 24-hour counseling services; athletic trainers now had to report to doctors rather than coaches; the incoming freshman class was the most diverse in university history. “The bottom line is that MSU is a dramatically better, stronger institution than it was one year ago,” he said.

[Read: Ex–Michigan State president charged with lying to investigators]

But even for the changes, Michigan State’s handling of the fallout from the Nassar tragedy has been a slow-rolling public-relations catastrophe. Since January of last year, revelation after revelation surfaced about the university’s handling of the Nassar case. The university claimed to hire an “independent investigator” to look into the case and assigned a university lawyer instead. An employee with ties to Nassar was also accused of sexual crimes. Simon was charged with lying to investigators. The number of applicants to the university dropped.

The board met on Thursday morning and voted to remove Engler immediately rather than allow him to serve until January 23, which he had requested in his resignation letter. The university must move on again. The crisis continues, and it’s become another interim president’s responsibility. Satish Udpa, an executive vice president at the university, has been tapped to take it on. The university is still looking for its next permanent president. But for now, as the trustee Brian Mosallam, one of the most outspoken critics of Engler, said during the meeting, the healing begins—again.

Science is sometimes caricatured as a wholly objective pursuit that allows us to understand the world through the lens of neutral empiricism. But the conclusions that scientists draw from their data, and the very questions they choose to ask, depend on their assumptions about the world, the culture in which they work, and the vocabulary they use. The scientist Toby Spribille once said to me, “We can only ask questions that we have imagination for.” And he should know, because no group of organisms better exemplifies this principle than the one Spribille is obsessed with: lichens.

Lichens can be found growing on bark, rocks, or walls; in woodlands, deserts, or tundra; as coralline branches, tiny cups, or leaflike fronds. They look like plants or fungi, and for the longest time, biologists thought that they were. But 150 years ago, a Swiss botanist named Simon Schwendener suggested the radical hypothesis that lichens are composite organisms—fungi, living together with microscopic algae.

It was the right hypothesis at the wrong time. The very notion of different organisms living so closely with—or within—each other was unheard of. That they should coexist to their mutual benefit was more ludicrous still. This was a mere decade after Charles Darwin had published his masterpiece, On the Origin of Species, and many biologists were gripped by the idea of nature as a gladiatorial arena, shaped by conflict. Against this zeitgeist, the concept of cohabiting, cooperative organisms found little purchase. Lichenologists spent decades rejecting and ridiculing Schwendener’s “dual hypothesis.” And he himself wrongly argued that the fungus enslaved or imprisoned the alga, robbing it of nutrients. As others later showed, that’s not the case: Both partners provide nutrients to each other.

Today, such a relationship is called a “symbiosis,” and it’s considered the norm rather than the exception. Corals rely on the beneficial algae in their tissues. Humans are influenced by the trillions of microbes in our guts. Plants grow thanks to the fungi on their roots. We all live in symbiosis, but few organisms do so to the same extreme degree as lichens. If humans were to spend their lives in the total absence of microbes, they’d have many health problems but would unquestionably still be people. But without its alga, a lichen-forming fungus bears no likeness to a lichen. It’s an entirely different entity. The lichen is an organism created by symbiosis. It forms only when its two partners meet.

Or does it?

Lichen-forming fungi all belong to a group called the ascomycetes. But in 2016, Spribille and his colleague Veera Tuovinen, of Uppsala University, found that the largest and most species-rich group of lichens harbored a second fungus, from a very different group called Cyphobasidium. (For simplicity, I’ll call the two fungi ascos and cyphos). The whole organism resembles a burrito, with asco fillings wrapped by a shell that’s rich in algae and cyphos.

For many, it was a game-changing discovery. “The findings overthrow the two-organism paradigm,” Sarah Watkinson of the University of Oxford told me at the time. “Textbook definitions of lichens may have to be revised.” But some lichenologists objected to that framing, arguing that they’d known since the late 1800s that other fungi were present within lichens. That’s true, Spribille countered, but those fungi had been described in terms that portrayed them as secondary to the main asco-alga symbiosis. To him, it seemed more that the lichens he studied have three core partners.

But that might not be the whole story, either.

Look on the bark of conifers in the Pacific Northwest, and you will quickly spot wolf lichens—tennis-ball green and highly branched, like some discarded alien nervous system. When Tuovinen looked at these under a microscope, she found a group of fungal cells that were neither ascos nor cyphos. The lichens’ DNA told a similar story: There were fungal genes that didn’t belong to either of the two expected groups. Wolf lichens, it turns out, contain yet another fungus, known as Tremella.

[Read: Is this fungus using a virus to control an animal’s mind?]

This isn’t entirely new. Over the years, other lichenologists have detected Tremella in wolf lichens, but only ever in three specimens, and only in the context of abnormal swollen structures called galls. “It was thought to be a parasite,” Tuovinen says. “But we found it in completely normal wolf lichens that don’t have any kinds of bumps.” Tremella is right there in the shell of the lichen burrito, next to the cyphos. It seems to make extremely close contact with the algae, hinting at some kind of intimate relationship. And it’s everywhere. Tuovinen analyzed more than 300 specimens of wolf lichens from the U.S. and Europe, and found Tremella in almost all of them.

Wolf lichens are among the most intensively studied of all lichens, so how could such a ubiquitous component have been largely missed? The problem, Tuovinen says, is that under a normal microscope, “the fungal cells all look the same.” She saw it only when she tagged the lichens with glowing probes that were designed to recognize Tremella genes. And she knew to do that only after finding those genes amid wolf lichen DNA. Earlier genetic studies, she says, might have missed them because they had specifically focused on the genes of the ascos. “There hadn’t been a reason to expect anything else based on the knowledge at the moment,” she says.

It’s an exciting discovery, says Erin Tripp, a lichenologist from the University of Colorado Boulder, but it’s still unclear what Tremella is actually doing. Most likely, she argues, it’s an infection, albeit a very widespread one. The alternative is that Tremella is a core part of the lichen. “This would, of course, be very exciting,” Tripp says, but to demonstrate that, the team would need to try to reconstitute wolf lichens with or without Tremella or, alternatively, use gene-editing techniques to disable the fungus and check how the lichens respond. “Without this sort of experimental approach, it seems premature to suggest that Tremella represents a third, fourth, or whatever-th symbiont.”

Tuovinen agrees that one shouldn’t overplay Tremella’s role. But she argues that lichenologists have too readily downplayed such organisms. More than 1,800 species of non-asco fungi have been described within lichens, and they’ve been labeled with terms that imply some kind of externality: commensalistic. Parasymbiotic. Endolichenic. Lichenicolous. If they’re not ascos, “we somehow just decided, without testing, that they’re parts of a lichen that can be excluded,” Tuovinen says. “We really don’t know that.”

[Read: The ex-anarchist construction worker who became a world-renowned scientist]

“Language matters a lot when dealing with these organisms,” Spribille, now at the University of Alberta, adds. “If we set up our language so that our definition of a lichen is fixed, and these other elements are extrinsic, we’re setting ourselves up to find that they’re extrinsic.” He thinks that researchers should move away from “the imperative of classification” and the compulsion to shoehorn organisms into fixed buckets. He suspects that the relationships between all the components of a lichen are probably highly contextual—beneficial in some settings, neutral or harmful in others.

That’s a lesson other scholars of symbiosis should also heed. There’s a tendency to categorize the bacteria within an animal’s microbiome as good or bad, as beneficial mutualists or harmful pathogens. But such labels imply an inherent nature that likely doesn’t exist. The same microbes can be benign or malign in different contexts, or perhaps even at the same time. Biology is messy—as are lichens.

Tripp agrees that “we, as a community of lichen biologists, need to revisit the role of all symbionts in the lichen microcosm.” No matter how one describes Tremella and other lichen-associated fungi, it’s clear that they do affect the form and function of the lichen as a whole. How they do so is “the great unsolved problem” of lichenology, says Anne Pringle of the University of Wisconsin at Madison. “Are the multiple species of fungi interacting mutualistically? With each other? With the algae? Are some parasites? Probably the answer to all questions is yes. Regardless, the data support an emerging consensus: Lichens are ecosystems as well as organisms.”

How many partners are there in a lichen? “I don’t know, but I think it depends on the lichen,” Spribille says. “I don’t expect there to be any one configuration that makes a lichen, a lichen.” That’s especially likely because lichens have evolved many times over, from different lineages of ascos that independently formed partnerships with different algae, over hundreds of millions of years. To expect them all to share the same basic plan is like expecting birds to be the same as fish.

They’re especially hard for us to understand because they’re so different from the organisms we’re familiar with. Unlike animals and plants, lichens don’t really have tissues. They don’t grow from embryos, and instead form through fusion. Different combinations create different forms—brittle or flexible, flat or round—and these traits are likely just as important to them as wings or legs or eyes are to animals. “We don’t understand their needs,” Spribille says. “In the absence of that, it’s difficult to say what kinds of configurations are within the realm of the possible.” And we can only ask questions that we have imagination for.

A government shutdown that most Americans oppose, on behalf of a border wall that most Americans oppose, might be the logical end point for a president and a political party that appears more and more unconcerned about attracting support from a majority of the public.

Donald Trump’s decision to precipitate a government shutdown over his demands for money to build a border wall, and the virtual absence of congressional GOP resistance to his approach, shows how comfortable the president and the broader Republican Party around him have grown in pursuing goals that face majority opposition in polls—so long as they retain the backing of their core supporters.

Attracting and sustaining majority support has traditionally represented a North Star for American presidents. The showdown over the shutdown, perhaps more than any earlier decision, makes clear that Trump is setting his course by a very different compass. Trump has abandoned any pretense of seeking to represent majority opinion and is defining himself almost entirely as the leader of a minority faction.

That carries big long-term risks for the GOP, as the Democratic gains in the House last November demonstrated. But because the structure of the Senate and the Electoral College disproportionately favors the older, non-college-educated, evangelical, and rural white voters who comprise his faction, Trump’s approach could sustain itself for years. And that promises a steady escalation in political conflict and polarization as Republicans tilt their strategy toward the demands of an ardent minority—and lose the moderating influence of attempts to hold support from a majority of Americans.

[Read: Trump’s wall could cost him in 2020]

Over the past 20 years, energizing the base has grown more important in both parties. In retrospect, the turning point might have been 1998, when Republicans in the House of Representatives voted to impeach then-President Bill Clinton at a time when most Republican partisans supported the move but a preponderance of all Americans opposed it. George W. Bush consistently pursued goals, such as his second tax cut, that attracted virtually no Democratic support. Barack Obama passed the Affordable Care Act without a single Republican vote at a time when polls generally showed that, at best, only a narrow plurality of Americans supported the law.

But Trump has taken this concentration on his base supporters to unprecedented heights. Elected with only 46 percent of the popular vote, he is now the first president in the history of Gallup polling to never reach majority approval of his job performance during his first two years. In November’s midterm election, Trump’s approval rating among voters stood at 45 percent, with 54 percent disapproving. Attitudes about Trump almost completely correlated with the vote in House races: Republicans carried 44.8 percent of the total House popular vote, while Democrats carried 53.4 percent. The Democratic votes helped the party capture 40 seats, their biggest gain since the Watergate-era election of 1974.

Trump’s decision to shut down the government over the wall, and the widespread Republican acquiescence that followed, is especially revealing because it came in response to those losses. The GOP was decimated in white-collar suburban districts largely because swing voters who broke narrowly for Trump in 2016—particularly independents and college-educated whites—stampeded toward the Democrats.

That historic rout, centered in economically thriving places Democrats have rarely if ever won before, has understandably set off alarms among Republican strategists and consultants. “I can assure you there is a huge focus on what happened in suburbia: What happened between I-5 [on the West Coast] and I-95 [on the East Coast],” the Republican pollster Gene Ulm told me. “Nobody has missed that fact. That’s not lost on anybody.”

The small exception to that consensus might be Trump and the GOP leadership in the House and the Senate. Because in precipitating a shutdown over the wall, they have embraced a cause deeply unpopular with all of the groups that drove the Democratic gains in suburbia last fall.

In the latest round of national polls, at least 55 percent, and sometimes as high as 59 percent, of independents have said they oppose the wall. Opposition to the wall among college-educated whites has ranged from just over half, in the latest Quinnipiac University and ABC/Washington Post surveys, to 63 percent, in recent polls from the Pew Research Center and CNN. Resistance to the wall consistently runs above 60 percent among the Millennial and minority voters who also broke decisively toward Democrats in November.

In all, no recent survey has found that more than 43 percent of Americans support the wall. That suggests that, as with his overall job performance, Trump has made virtually no progress in broadening his audience since his election: In the exit poll on Election Day 2016, 41 percent of voters said they supported a border wall.

The shutdown is even less popular: In a PBS/Marist poll released Wednesday, 70 percent rejected closing the government to advance a particular policy goal, as Trump has. And by a consistent margin of about 25 percentage points, more Americans blame Trump than congressional Democrats for the impasse, according to roughly a half-dozen recent surveys. Trump’s overall approval rating has fallen to 37 percent in the latest surveys from CNN, Gallup, and Pew, and registered slightly above that in Quinnipiac’s poll.

The Democratic pollster Mark Mellman told me that throughout American history, it hasn’t been unusual for the political system to bottle up policies that most Americans support. One modern example is universal background checks for gun sales. Less typical, he said, is for political leaders to insist on driving through an idea, such as the border wall, that most Americans have clearly indicated they reject. “It’s mind-boggling to me that the whole Republican Party, with a couple of exceptions, has gone along with closing the government to spend money on something most people oppose,” he said.

The most striking aspect of the shutdown might not be Trump’s indifference to majority opinion: He’s demonstrated over and over that he is comfortable playing on the short side of the field so long as his core supporters are energized. Instead, this confrontation might be remembered as the moment that crystallized how much of the Republican Party shares his disregard about appealing to a national majority. As Mellman noted, only a handful of Republicans in either chamber have broken from Trump’s shutdown strategy so far, and even they have dissented only gently.

That hesitance might reflect several factors, including Republicans’ fear of generating a primary challenge by challenging Trump. But even more important might be the extent to which the GOP is now sheltered from the implications of majority opinion. Especially under Trump, the Republican Party is folding in on itself. It is growing more and more dependent on its core supporters and more reliant in both the House and Senate on strongly Republican areas where those voters predominate.

Just three House Republicans (Brian Fitzpatrick in Pennsylvania, John Katko in New York, and Will Hurd in Texas) represent districts that voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016. Even more strikingly, just two House Republicans (Mario Diaz-Balart in Florida and Don Bacon in Nebraska) are left in districts that Trump carried by fewer than 5 percentage points, according to figures provided by TargetSmart, a Democratic voter-targeting firm. After the party’s suburban wipeout in November, more than 85 percent of House Republicans now represent districts that are whiter than the national average, and more than 75 percent hold seats with fewer college graduates than average, according to census figures.

In the Senate, just two Republicans are left in the 20 states that voted for Clinton over Trump in 2016: Susan Collins of Maine and Cory Gardner of Colorado, both of whom face reelection in 2020. Just five other Republicans hold Senate seats in states that backed Trump in 2016 but have voted Democratic in most presidential elections since 1992.

The remaining GOP senators represent states that have voted Republican in most of the past seven elections. And fully 44 of the 53 total Republican senators were sent to Washington by states that have voted for the GOP at least five times in the past seven elections. That orients the bulk of GOP senators toward the opinion of partisan Republicans—most of whom support the wall and using a shutdown to pursue it—rather than the nation overall.

[Read: Why hasn’t Trump folded?]

This narrow focus is self-reinforcing, because it virtually ensures that Republicans will continue to retreat from places where the Trump coalition can’t win. Not long ago, Colorado was a swing state. But in November, fueled by a powerful backlash against Trump among independent voters and high turnout among Millennials, Democrats won every statewide office for the first time since 1936 and captured both chambers of the state legislature. “The only thing comparable was the Watergate election of 1974, but even that wasn’t as bad, because we retained one statewide office and a one-vote majority in the state Senate,” says Dick Wadhams, the former state GOP chair. “So this was even more sweeping than Watergate.”

Wadhams says he can imagine a scenario where Republicans recover in Colorado for 2020 if Democrats pick a presidential nominee too liberal for the state’s swing voters. But he sees no signs that Trump will expand the coalition supporting him or the GOP in the state. Trump’s focus on satisfying a distinct minority, Wadhams says, “is problematic with a state like Colorado, with the kind of electorate we have, the dynamic electorate we have, the huge numbers of people who are moving here.”

John Thomas, a Republican consultant who works in Orange County, California—where the GOP was swept in last year’s House races—takes a similar view. He sees several dynamics that could allow Republicans to recover in the longtime conservative bastion in 2020, including overreach by House Democrats, especially on spending, and less intense fundraising from donors for House races during a presidential year. But he concedes that none of those factors might matter much if Trump continues to alienate the region’s diverse and well-educated voters. It “really comes down to, What do you think about Trump?” Thomas says.

Winning without majority support is becoming a way of life for the GOP. Republican presidential candidates (Bush in 2000 and Trump in 2016) have won the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote in two of the past five presidential elections, after the country had experienced such a split only three times in the previous 200-odd years. Everything Trump has done in office—and especially with the shutdown—suggests that he’s comfortable trying to squeeze out another Electoral College victory without winning the popular vote. And given the GOP’s continued erosion in blue California, and the Democrats’ growing competitiveness in red-leaning Texas, the odds of Trump winning the popular vote in 2020, even if he is reelected, seem very small, according to many experts in both parties.

In the Senate, the GOP’s reliance on small states less touched by demographic and cultural change has allowed it to hold most seats even if it doesn’t win most votes nationwide. (One comprehensive recent study found that 2017 was the first time in the chamber’s history that the senators who approved passed legislation and nominations represented less than half of the country’s population.) Even in the House, gerrymandering and the concentration of Democratic voters in large urban areas has muffled the GOP’s exposure to national opinion, though the party’s collapse in suburbia overwhelmed those defenses last fall.

The extended stalemate over the shutdown, despite the clear signals from polls, offers a powerful gauge of how much more turbulent politics might become if the GOP concern about majority opinion continues to dwindle. And the more Republicans sublimate that opinion to efforts to mobilize their base, the more pressure will grow from Democrats who want their party to follow the same model the next time it holds the White House. Trump is demonstrating how quickly extremism can flourish once a president abandons even the aspiration of representing a majority of Americans. The shutdown is unlikely to provide the last, or even the most damaging, example of where that can lead.

Impeachment is a powerful tool. The time to wield it is now, argues the Atlantic senior editor Yoni Appelbaum. In the latest Atlantic Argument, Appelbaum invokes Andrew Johnson’s impeachment in 1868 to make the case for democratically removing President Donald Trump from office. Appelbaum underscores that this measure is not meant to resolve a policy dispute; rather, it is an attempt to rectify the problem of Trump’s inability to discharge the basic duties of his office.

“The president is unfit for the office he holds,” Appelbaum says in the video. “Congress needs to act now and open an impeachment inquiry.”

For more, read Appelbaum's Atlantic article, “The Case for Impeachment.”

LONDON—Early on in Brexit, Channel 4 and HBO’s almost inappropriately entertaining movie about Britain’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union, we flash back in time to 1975, when ordinary citizens are being interviewed about another historic referendum on Europe. “I don’t really know what I’m voting for,” one voter sheepishly confesses. “I don’t really see what good it’s going to do us,” another adds, somewhat huffily.

Here, in a nutshell, is the perpetual nature of Britain’s relationship with the EU. It’s confused. Cranky. Doggedly pessimistic. And things have only gone downhill since then. In the two and a half years since 52 percent of the nation voted to leave the world’s largest trading bloc, the debate over Brexit has become the Groundhog Day no one can wake up from, with its recriminations and unsolvable paradoxes and parliamentary chaos. Even the reality that Britain is lurching painfully but certainly toward financial free fall if no agreement for leaving emerges before March 29 hasn’t shifted the political mechanisms out of gridlock. It’s a polarizing, infuriating, exhausting mess.

How, you might ask, does someone make a decent movie out of that?

It helps that the director of Brexit is Toby Haynes, who’s handled similarly tense and nightmarish scenarios in episodes of Black Mirror and Sherlock. The inscrutably magnetic starring presence of Benedict Cumberbatch is another mitigating factor. But really, the man pulling magic from national meltdown is James Graham. The genial 36-year-old playwright is beyond rising-star status at this point, having seen two of his plays run simultaneously in the West End last year: Ink, a drama about a young Rupert Murdoch that arrives on Broadway in April, and Labour of Love, which charted the state of one of Britain’s main political parties over 27 years. Graham, The Guardian’s Michael Billington wrote in his review of the latter, “has a rare capacity to recreate pivotal moments from our past.” But as Brexit demonstrates, he also has an uncanny gift for writing history in real time, tuning out the noise and lasering in on the most vital elements of the story.

This is, he tried to explain to me in a phone interview hours before Prime Minister Theresa May’s calamitous Brexit vote in Parliament on Tuesday (spoiler: she lost), not such a novel thing. “It’s what Shakespeare did, what the poets have always done,” he said. “You put human beings against the backdrop of nation-changing events, and the personal and the political begin to speak to each other, and make sense of each other through the juxtaposition.” Simple. But Shakespeare, not to disparage him, wasn’t dealing with a story involving emerging algorithms, behavioral micro-targeting, and allegations of campaign-finance transgressions that are still being investigated. That Graham has managed to make a functioning drama out of Brexit, let alone such a riveting one, feels a little bit miraculous.

Possibly it’s because he foregrounds a side of the story—and a crucial player—about which remarkably little has been said. Cumberbatch plays Dominic Cummings, the campaign director of Vote Leave (the government-designated official campaign in favor of leaving the EU). A balding, sandy-haired eccentric in a high-visibility cycling vest, Cummings—Brexit argues—is actually a sophisticated architect of chaos, the shadowy Blofeldian author of so much political pain. “In a different branch of history, I was never here,” Cummings tells the camera early in the film. “Some of you voted differently and this never happened.” But since it did, he’s here to explain. “Everyone knows who won, but not everyone knows how.”