A Nike lançou seu primeiro hijab esportivo em dezembro de 2017, anunciado com elegantes fotos preto e branco de atletas muçulmanas bem-sucedidas vestindo o Pro Hijab decorado com o icônico swoosh (nome do logotipo famoso da marca). No mesmo mês, o TSA (Transport Security Administration) selecionou 14 mulheres que vestiam hijabs para uma revista no aeroporto Newark; elas foram, então, apalpadas, revistadas e detidas por duas horas.

Entre fevereiro e março do ano passado, Gucci, Versace e outras marcas de luxo em suas respectivas semanas de moda outono/inverno trouxeram às passarelas basicamente só mulheres brancas vestindo véus semelhantes a hijabs. Naquela mesma época, duas mulheres entraram com um processo de direitos humanos contra a cidade de Nova York por um incidente que em a polícia nova-iorquina as forçou a remover seus hijabs para fotos de fichamento policial.

A Gap, marca de roupas famosa por seu ethos totalmente americano, mostrou em suas propagandas de volta às aulas do ano passado uma menina sorridente vestindo um hijab. Enquanto isso, crianças eram forçadas a sair de uma piscina pública em Delaware; foi dito a elas que seus hijabs poderiam entupir o sistema de filtragem da água.

Ao vender roupas recatadas ou colocando em foco as hijabis (mulheres que vestem o véu) em propagandas, a indústria de roupas dos Estados Unidos está convocando mulheres muçulmanas para se tornaram o seu mais novo nicho consumidor. Para acessar o potencial multibilionário do mercado consumidor muçulmano nos EUA, grandes varejistas se posicionaram como refúgios conscientes socialmente para muçulmanos, operando a partir da motivação de lucro ao invés do imperativo moral.

Muitas mulheres muçulmanas, principalmente aquelas que cresceram após o 11 de setembro, podem achar a inclusão delas enquanto consumidoras um alívio da islamofobia diária. No entanto, as representações difundidas por empresas varejistas são redutoras da identidade dos muçulmanos americanos. A algumas muçulmanas que se conformam com as expectativas de patriotismo e consumismo é garantida a visibilidade, enquanto outras, como mulheres muçulmanas negras, são apagadas da narrativa do islã nos EUA. No meio disso, muçulmanos cujo trabalho é explorado fora do país desaparecem da consciência corporativa.

O mercado consumidor muçulmanoEm fevereiro, a Macy’s se tornou a primeira loja de departamentos americana a vender uma linha de roupas recatadas, chamada Coleção Verona. A loja foi amplamente elogiada como “inclusiva” e que estaria “levando a diversidade a sério”. O site Refinery29 disse que “É ótimo ver a Macy’s realmente dando passos em direção a advogar as causas que diz acreditar”.

Coleção Verona da loja Macy’s.

Fotos: Lisa Vogl/Cortesia de Lisa Vogl

A Macy’s divulgou a Coleção Verona logo após anunciarem que diversas lojas fechariam em 2018 (mais de 120 lojas fecharam as portas desde 2015). Uma semana antes do lançamento, as ações da varejista bateram seu menor valor de 2018. Mas, após a divulgação, as coisas pareciam estar melhorando para a empresa. “Nesse momento, para investidores, a nova linha de roupas deve ser tratada com cautelosa empolgação pelo que pode significar para a empresa de agora em diante”, disse um analista de negócios.

A instabilidade financeira da Macy’s ao começar a vender hijabs e roupas recatadas coloca em questão o motivo por trás da repentina preocupação em suprir o mercado de consumidoras muçulmanas. Por que agora?

“Parece uma forma de gerar publicidade colocando uma imagem inclusiva, tentando fazê-los parecer mais relevantes”, disse ao Intercept Sylvia Chan-Malik, autora de “Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam” (“Ser muçulmana: Uma história cultural das mulheres de cor no Islã Americano”, em tradução livre). “Mas talvez isso seja cínico, porque eu conheço muitas mulheres muçulmanas que ficaram muito felizes [com a propaganda]. Eu só não sei quais são as intenções.”

Além da Nike, Gap e designers famosos, há diversos exemplos recentes da indústria de varejo e de moda nos EUA “flertando” com mulheres muçulmanas que se vestem de modo mais recatado. Em 2016, a semana de moda de Nova York apresentou o seu primeiro desfile completamente com hijabs da designer indonésia Anniesa Hasibuan. Na mesma época, a marca CoverGirl trouxe a blogueira de beleza Nura Afia como sua mais nova embaixadora da marca. Em maio do ano passado, a rede H&M lançou uma linha de roupas recatadas próximas ao período do Ramadã.

Desde o início dos anos 2010, empresas multinacionais ocidentais supriram as necessidades de consumidores muçulmanos após consultores de marketing os identificarem como um grupo de influência demográfica com crescente poder de compra. De acordo com o último Thomson Reuters State of the Global Islamic Economy Report, muçulmanos ao redor do mundo gastaram cerca de 254 bilhões de dólares em 2016, o que estaria previsto para aumentar para 373 bilhões em 2022.

Varejistas ocidentais concentraram a maior parte de seu alcance muçulmano em consumidores estrangeiros. Dolce & Gabbana, Tommy Hilfiger e DKNY estão entre as marcas que venderam coleções-cápsula (coleção composta por itens de vestuário fora das grandes coleções de estação) ou roupas recatadas já estocadas exclusivamente em suas lojas do Oriente Médio. No último verão, a MAC Cosmetics lançou um glamouroso tutorial de maquiagem para o suhoor, a refeição antes do amanhecer durante o Ramadã, tendo como alvo mulheres na região do Golfo.

Pesquisas de consumo no mercado americano revelaram uma oportunidade similar de lucro. Em 2013, Ogilvy Noor, a “divisão islâmica de marca” da empresa de propaganda Ogilvy, estimou que o poder de compra de americanos muçulmanos seria de 170 bilhões de dólares. DinarStandard e o American Muslim Consumer Consortium reportaram que muçulmanos americanos gastaram 5,4 bilhões em vestuário naquele mesmo ano.

Fotos: Cortesia de Rawan Al Sadi

A Ogilvy Noor determinou que millenials muçulmanos estão levando o consumismo adiante com sua crença coletiva de que “fé e modernidade caminham juntas”.

“Se eu fosse escolher uma pessoa que represente a vanguarda dos muçulmanos do futuro, seria uma mulher: com boa educação, entendida em tecnologia, cosmopolita, determinada a definir seu próprio futuro, leal à marca e consciente que seu consumo diz algo importante sobre quem ela é e como ela escolhe viver sua vida”, explicou Shelina Janmohamed, vice-presidente da Ogilvy Noor, que é muçulmana. “As consumidoras que são alvo dessas marcas são jovens, estilosas e estão prontas para gastar seu dinheiro”.

A abordagem da Ogilvy Noor busca resumir quem essas jovens muçulmanas são, o que pode ser, então, monetizado por empresas. O poder econômico surpreendente do mercado muçulmano é o fator determinante dos esforços do varejo em explorá-lo – sendo algo menor como as muçulmanas podem de fato se beneficiar disso. Mas, para muitas jovens muçulmanas, visibilidade de consumo pode demonstrar um reconhecimento daquilo que é convencional assim como a sensação de pertencimento, não importando as intenções corporativas.

“Talvez eu me sinta mais segura”Enquanto varejistas são, no fim das contas, incentivados pelo lucro, marcas de roupas e cosméticos também estão fornecendo mais opções para mulheres que escolhem se cobrir, assim como satisfazendo os desejos delas por representação, disse Elizabeth Bucar, autora de “Pious Fashion: How Muslim Women Dress” (“Moda devota: Como as muçulmanas se vestem”, em tradução livre).

“Muçulmanos são uma grande parte da população americana hoje – eles são visíveis”, disse Bucar, professora associada à Universidade Northeastern, ao Intercept. “Eles estão se candidatando a cargos políticos, são nossos colegas de trabalho, nossos vizinhos e, do ponto de vista do varejo, eles também são consumidores.”

Muitas muçulmanas celebram, e ativamente participam, dos esforços para reconhecê-las como consumidoras. Blogueiras muçulmanas de moda e beleza no Instagram e no YouTube promovem marcas para centenas de milhares de seguidores. A designer da Coleção Verona, Lisa Vogl, e a modelo Mariah Idrissi, estão dentre aquelas que tiveram sucesso comercial em parceria com grandes marcas.

Em setembro, o Museu Memorial M. H. de Young em São Francisco abriu a primeira grande exibição em moda muçulmana contemporânea, mostrando que o vestuário feminino muçulmano é um tópico legítimo de interesse nos EUA. “Nós queríamos compartilhar com o restante do mundo o que temos visto na moda muçulmana de forma a criar um entendimento melhor sobre ela”, disse o antigo diretor do museu, Max Hollein, ao New York Times.

Foto: Cortesia dos Museus de Belas Artes de São Francisco

Visibilidade de consumo também pode demonstrar um passo adiante na inclusão de muçulmanos como americanos em tempos politicamente hostis, principalmente para a geração que cresceu durante a guerra ao terror, quando a maior parte das representações mostravam muçulmanos como terroristas estrangeiros e uma ameaça à segurança nacional.

“Isso é uma validação muito grande em um nível pessoal para mulheres muçulmanas que usam véu, que sofrem com comentários, críticas duras e a violência que elas encontram todos os dias”, disse Chan-Malik, professora associada na Universidade Rutgers. “É quase um senso prático de alívio, algo como ‘Ah, se isso se tornar normal, talvez eu me sinta mais segura’”.

Que a representação crescente é significativa para algumas muçulmanas é algo que não pode ser ignorado. No entanto, quem é visto e como é visto é algo que expõe as lógicas subjacentes do capitalismo que nivelam a falsa visibilidade de que as mulheres muçulmanas são as mais comercializáveis.

O “fetiche pelo hijab”O mercado homogeniza as muçulmanas, transformando diversidade em um produto que pode ser facilmente digerido. “Certos tipos de representação e visibilidade são privilegiados, enquanto outros são tidos como indesejáveis”, escrevem Ellen McLarney, professora associada da Universidade Duke e Banu Gökariksel, da Universidade da Carolina do Norte. “Identidades muçulmanas desagradáveis às sensibilidades do mercado são excluídas, frequentemente levando a maiores marginalizações nas interseções de classe, raça e etnicidade.”

Isso fica evidente em como as indústrias da moda e da beleza garantem visibilidade a certas mulheres muçulmanas. Ao escrever sobre o “fetiche pelo hijab” na cultura de consumo, a colunista do jornal The Guardian, Nesrine Malik, descreveu como as representações de mulheres muçulmanas em propagandas se enquadram em “uma imagem, com a luz perfeita, de uma mulher vestindo hijab cheia de filtros, bonita, burguesa e de pele clara”.

Na verdade, a maior parte das muçulmanas nos Estados Unidos nem sempre usa o véu em público; um quinto dos americanos muçulmanos são negros; quase metade dos americanos muçulmanos declararam renda de menos de 30 mil dólares no ano passado; e muitos americanos muçulmanos se identificam como queer, transgênero ou pessoas com não-conformidade de gênero.

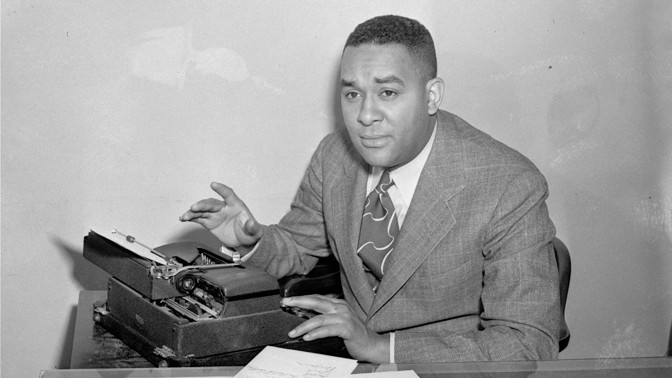

Apesar do fato de que mulheres muçulmanas negras são amplamente ausentes da cultura de consumo comum, diz Kayla Wheeler, professora assistente na Universidade Grand Valley State, as mulheres da Nação do Islã e do Moorish Science Temple of America alicerçaram as fundações para a moda muçulmana nos EUA décadas atrás.

“A Nação do Islã tentou usar roupas para dar a mulheres negras uma nova identidade respeitável que lhes foi negada pela supremacia branca, para que elas pudessem … ir contra os estereótipos de mulheres negras como promíscuas, assexuadas ou nem mesmo mulheres ou humanos reais”, diz Wheeler, que pesquisa a moda muçulmana negra.

A modelo somali-americana Halima Aden e a esgrimista olímpica Ibtihaj Muhammad, junto das designers Nzinga Knight, Eman Idil e Lubna Muhammad, estão entre as poucas mulheres negras muçulmanas que ganharam visibilidade na indústria da moda.

“Mulheres negras muçulmanas são triplamente mais vulneráveis nos EUA a ataques racistas, misóginos e islamofóbicos.”Wheeler disse que os véus de mulheres negras muçulmanas podem ser racialmente distintos em estilos de dobrar e ainda em tecidos – nuances que são obscuras nas imagens comerciais com a predominância de mulheres do Oriente Médio e do sul da Ásia. Em meio a isso, mulheres negras muçulmanas são triplamente mais vulneráveis nos EUA a ataques racistas, misóginos e islamofóbicos (no mês passado, um homem branco apontou uma arma para um grupo de adolescentes negros muçulmanos, incluindo meninas que usavam véu, em um McDonald’s em Minnesota).

“Negros muçulmanos não são vistos com tanta simpatia como os muçulmanos pardos,” disse Wheeler ao Intercept. “Todos enfrentam a islamofobia, mas quando se adiciona a anti-negritude e suspeitas do islã negro não ser o islã real, eles se tornam não apenas uma ameaça estrangeira, mas uma ameaça local.”

A postura corporativa em relação a grupos marginalizados – o que a professora de direito Nancy Leond, da Universidade de Denver, descreve como capitalismo racial – é, há muito tempo, uma prática de negócios para persuadir grupos minoritários a se tornaram leais às marcas e consumidores liberais a comprar produtos como uma afirmação política.

Uma imagem de uma propaganda da L’Oréal Paris com Amena Khan.

Em janeiro, a L’Oréal Paris anunciou sua “única e revolucionária” campanha de produtos para cabelos com a modelo e influenciadora digital Amena Khan. No anúncio, ela vestia um hijab rosa claro, com um blazer rosa, em frente a um fundo também rosa. Em uma semana, Khan deixou de participar da campanha após seus tuítes criticando Israel pelos ataques em Gaza em 2014 virem a público. Em declaração, a L’Oréal Paris concordou com a decisão de Khan de se retirar, dizendo que a empresa está “comprometida com a tolerância e o respeito a todas as pessoas.”

Marcas “querem o rosto, mas não querem a política complexa, a identidade ou a voz por trás dele”, disse Hoda Katebi, blogueira de moda política e organizadora comunitária, ao Intercept, referindo-se às suas próprias experiências com marcas que a convidaram para trabalhar com ou ser modelo de suas roupas. “Uma vez que uma mulher muçulmana se impõe, eles acabam com isso.”

A fetichização do hijab descende de décadas de imagens estereotípicas que foram usadas para fortificar projetos imperialistas no Oriente Médio e políticas islamofóbicas e atitudes em solo americano. A interferência americana em países de maioria muçulmana e na guerra ao terror foi o contexto político em que varejistas e publicitários transformaram mulheres muçulmanas e suas roupas em commodities.

Foto: Bryan R. Smith/AFP/Getty Images

A representação das mulheres muçulmanas e do véu na cultura de consumo norte-americana mudou ao longo da história, junto com os interesses do império americano. O véu, que contempla uma miríade de formas de cobrir a cabeça, já recebeu vários significados, muitas vezes contraditórios: empoderador, opressivo, ameaçador, elegante, subversivo.

Por décadas, o mito da benevolência imperial informou a política externa dos EUA, ao lado de uma falsa preocupação com as mulheres muçulmanas e suas condições culturais, que serviram para promover os interesses em benefício da elite política e econômica.

O véu virou fetiche nos EUA durante o movimento feminino do Irã após a revolução de 1979, disse Chan-Malik ao Intercept. As mulheres se mobilizaram em uma semana de protestos após o aiatolá Khomeini, que substituiu o xá apoiado pelos Estados Unidos, Reza Pahlavi, estabelecer o uso compulsório do véu, impedindo-as de escolher se queriam ou não cobrir a cabeça.

Mulheres muçulmanas reunidas perto de uma placa com a imagem do aiatolá Komeini, durante uma manifestação no início de fevereiro de 1979, em Teerã, no Irã.

Foto: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

A mídia norte-americana focou no xador (véu que cobre todo o corpo, com exceção do rosto) como o símbolo da opressão a que as “pobres mulheres muçulmanas” eram submetidas sob o governo do aiatolá, escreve Chan-Malik em seu livro. “Os direitos das mulheres se tornaram um grito de guerra que podia ser utilizado pelos Estados Unidos para explicar o mal do Oriente Médio e o ‘terror’ do Islã.”

As imagens criadas e difundidas durante essa época estabeleceram um orientalismo americano que continua a formar uma ideia das mulheres muçulmanas como reprimidas e precisando de um salvador norte-americano.

Em seu livro “The Veil Unveiled: The Hijab in Modern Culture” (“O Véu Revelado: o Hijab na Cultura Moderna”, em tradução livre), a professora Faegheh Shirazi, da Universidade do Texas em Austin, lista uma série de estratégias de marketing anteriores ao 11 de setembro de 2001, baseadas em estereótipos orientalistas, que eram utilizadas para vender carros, computadores, perfume e até mesmo sopa: “a mulher misteriosa escondida atrás de seu véu, esperando para ser conquistada por um homem americano; a mulher submissa, forçada a se esconder atrás do véu; e a mulher genérica encoberta pelo véu, representando todos os povos e culturas do Oriente Médio.”

Após o 11 de setembro, a burca virou o símbolo mais visível da Guerra do Afeganistão, transformada em uma arma a mais para servir aos interesses imperiais do governo Bush. Em uma famigerada fala no rádio, a primeira-dama Laura Bush alegou que o Talibã “ameaçava arrancar as unhas de mulheres que usassem esmalte”, um detalhe sórdido sugerindo que inclusive produtos de beleza estavam sujeitos a um policiamento tirânico. Tirar o véu das mulheres afegãs representaria sua “liberdade”, bem como sua transformação em consumidoras.

Após a queda do Talibã, a indústria de beleza dos EUA agiu como um braço do império e aproveitou a oportunidade para exportar produtos e técnicas ocidentais ao Afeganistão. As revistas Marie Claire e Vogue, acompanhadas por empresas de cosméticos como Paul Mitchell e Estée Lauder, financiaram o “Beleza Sem Fronteiras”, uma escola em Cabul dedicada a ensinar mulheres como trabalhar em um salão de beleza, ignorando o fato de que esses salões já existiam no país. Xampus e maquiagens americanos se tornaram ferramentas para liberar mulheres muçulmanas.

Foto: Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

No início desta década, o véu ainda era visto com suspeita quando vestido por mulheres muçulmanas, mas em geral havia se transformado em uma commodity provocativa e frequentemente sexualizada. A “burca chique” aparecia em revistas de moda e passarelas e jogava com o choque gerado pelo véu, escreve McLarney. A marca de jeans Diesel lançou uma peça publicitária em 2013 com uma mulher branca tatuada, fazendo topless e usando um niqab, enquanto celebridades não-muçulmanas, incluindo Rihanna, Madonna e Lady Gaga, brincavam de vestir véus como se eles fossem fantasias. A manipulação capitalista, escreve McLarney, havia transformado o véu “de um emblema de profunda desumanização em uma expressão de moda, protesto e mesmo liberdade individual.”

As roupas das mulheres muçulmanas adquiriram um novo significado no governo Trump, que endossa tacitamente a exclusão, criminalização e ódio aos muçulmanos. O pedido de campanha de Trump por um registro de muçulmanos e uma “paralisação total e completa da entrada de muçulmanos nos Estados Unidos”, que se manifestou na prática com o banimento à entrada de viajantes muçulmanos no país, deu o tom da sua abordagem a muçulmanos nascidos nos EUA.

Em resposta, os progressistas transformaram a mulher muçulmana em um ícone feminista. A imagem estilizada de uma mulher usando uma bandeira americana como hijab, criada pelo artista de rua Shepard Fairey, apareceu sobre a multidão na Marcha das Mulheres como um símbolo de inclusão multicultural e resistência política. No entanto, como muitos já assinalaram, a imagem distorce a história de violência estatal e injustiça contra muçulmanos nos EUA e no exterior — e a cumplicidade do movimento feminista americano nisso tudo. A óbvia presença do poster em manifestações anti-Trump também evocava como muçulmanas-americanas são representadas de formas que podem ser danosas à comunidade.

A política da visibilidadeA visibilidade seletiva das hijabis reforça um falso binarismo entre muçulmanas “boas” e “más”, apoiando muçulmanas progressistas e militantes como toleráveis e benignas sem corrigir as percepções profundamente consolidadas de muçulmanos como terroristas e fanáticos. Embora a maioria dos americanos não conheça pessoalmente um muçulmano, o Pew Research Center destaca que eles são o grupo religioso visto da forma mais negativa. Um estudo recente também demonstrou que ataques terroristas perpetrados por alguém suspeito de ser muçulmano recebem uma cobertura 357% maior no noticiário.

“As pessoas amam muçulmanos bons e patriotas, que não ameaçam a branquitude, que não desafiam a violência histórica e sistemática sobre a qual o país foi construído”, diz Aqdas Aftab, que escreveu sobre hijab e capitalismo como membro da Bitch Media.

Enquanto mulheres muçulmanas são cada vez mais acolhidas na cultura de consumo, homens muçulmanos ainda são vistos como “figuras sexualmente frustradas, violentas, inerentemente patriarcais”, diz Nazia Kazi, autora do livro “Islamophobia, Race, and Global Politics” (“Islamofobia, Raça e Política Global”, em tradução livre) — esses estereótipos se materializam na continuada criminalização dos homens muçulmanos.

Os muçulmanos nos EUA vêm sendo monitorados por policiamento e vigilância patrocinados pelo Estado, escreve Kazi, e também pela “curiosidade, preocupação e observação cotidianos”. Quando se trata de mulheres muçulmanas, ela escreve, a observação se torna uma “fascinação voyeurista”.

“Mulheres muçulmanas, especificamente aquelas que usam o hijab, são uma fonte única de curiosidade e compaixão e preconceito e suposições islamofóbicas”, disse Kazi, que é professora na Universidade Stockton, ao Intercept.

Esse preconceito aumentou na era Trump, um momento em que retórica e política flagrantemente islamofóbicas coincidiram com um aumento na discriminação e abusos contra muçulmanos. O Conselho para Relações Americano-Islâmicas reportou um aumento de 17% em incidentes contra muçulmanos entre 2016 e 2017, uma tendência que continuava em 2018. Apenas neste ano, houve numerosos relatos de hijabis sendo assediadas, verbalmente abusadas, empurradas no metrô e atacadas, tendo seus hijabs arrancados.

Para Kazi, a abordagem das empresas de varejo diante da islamofobia “alavancou a hipervisibilidade”, ou aproveitou o exame minucioso dos muçulmanos para destacar os mais exemplares. Isso teve o efeito de tornar invisível “quão devastador a islamofobia é para as mais marginalizadas dentre as mulheres muçulmanas ao redor do mundo”, diz Kazi.

A indústria do vestuário, por exemplo, aumenta a visibilidade de algumas mulheres muçulmanas, enquanto esconde outras do público — aquelas cujo trabalho é explorado em fábricas de roupas em outros países.

Foto: Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images

A produção global da moda rápida depende de empregos escravizantes para trazer as últimas tendências das passarelas aos cabides do mundo. Gap e H&M usam fábricas em países de maioria muçulmana e foram acusados de violência baseada no gênero e abusos trabalhistas. A Nike, notória por depender há décadas de trabalhadores explorados, também utiliza fábricas em países predominantemente muçulmanos.

“Quem vai cobrar sua responsabilidade por pagar mal, exigir trabalho excessivo, e assediar seus empregados vulneráveis quando essas mesmas empresas são saudadas como inclusivas e progressistas?”, diz Aftab.

Muçulmanos que aplaudem a comercialização do hijab devem estarcientes da exploração dos trabalhadores muçulmanos do setor de vestuário, e também de como as grandes corporações estão tirando oportunidades de negócios pequenos e mantidos por muçulmanos, como Katebi, que organiza uma cooperativa de costura para mulheres refugiadas em Chicago. Isso inclui empresas como a Haute Hikab e a Sukoon Active, que vêm fazendo roupas recatadas e roupas esportivas há anos.

Ilhan Omar celebra com suas apoiadoras após sua vitória no 5º Distrito Congressional em Minneapolis, Minnesota, em 6 de novembro de 2018.

Foto: Karem Yucel/AFP/Getty Images

Aumentar a representação muçulmana não é apenas uma estratégia pouco efetiva para combater a islamofobia, mas também é perigosa, diz Kazi, pois confunde a islamofobia como uma visão individual, ao invés de um aparato estrutural.

“A hipervisibilidade de muçulmanos está inegavelmente ligada ao clima político”, ela diz. “Então, enquanto o público lança esse olhar sobre muçulmanos nos EUA, o que sai da conversa são as histórias políticas, a desigualdade regional, as histórias de supremacia branca e raça”.

Mulheres muçulmanas encabeçam a vinda dessas questões para o discurso político de massa, particularmente na política eleitoral e nas organizações de base. Rashida Tlaib, do Michigan, e Omar Ilhan, de Minnesota, que em 3 de janeiro se tornaram as primeiras mulheres muçulmanas no Congresso dos EUA, concorreram com plataformas progressivas que incluíam um salário mínimo de 15 dólares por hora, “Seguro-saúde para todos”, e a abolição da Agência de Imigração e Alfândega dos Estados Unidos.

Katebi descreveu sua visão para uma mudança sistêmica: aqueles que fazem arte e aqueles que fazem política fazendo parcerias com as comunidades para garantir ganhos materiais. “Nossa liberação”, ela diz, “não virá de corporações capitalistas e multibilionárias encabeçadas por gente branca”.

Liberdade e justiça, para muçulmanos e não-muçulmanos, serão conquistadas nas urnas e no chão — e não no caixa de uma loja.

Tradução: Maíra Santos

The post Vendendo a mulher muçulmana: Hijabs e moda recatada são a nova tendência na era Trump appeared first on The Intercept.

Em 11 de dezembro de 1981, em El Salvador, uma unidade militar salvadorenha criada e treinada pelo Exército dos EUA começou a abater todas as pessoas que encontrou em um vilarejo remoto chamado El Mozote. Antes de assassinar as mulheres e as meninas, os soldados as estupravam repetidamente, incluindo algumas de apenas 10 anos de idade, brincando que suas preferidas eram as de 12 anos. Uma testemunha descreveu um soldado atirando uma criança de 3 anos para o alto e a empalando com sua baioneta. O número final de mortos foi de mais de 800 pessoas.

O dia seguinte, 12 de dezembro, foi o primeiro dia de trabalho para Elliott Abrams como secretário de Estado adjunto para os direitos humanos e assuntos humanitários no governo Reagan. Abrams entrou em ação, ajudando a encobrir o massacre. Em depoimento ao Senado, Abrams disse que notícias a respeito do que havia acontecido “não tinham credibilidade” e que tudo estava sendo “significativamente mal utilizado” como propaganda por guerrilheiros antigovernamentais.

Na sexta-feira passada, o secretário de Estado Mike Pompeo nomeou Abrams como enviado especial dos Estados Unidos para a Venezuela. Segundo Pompeo, Abrams “será responsável por todas as coisas relacionadas aos nossos esforços para restaurar a democracia” na nação rica em petróleo.

A escolha de Abrams envia uma mensagem clara à Venezuela e ao mundo: o governo Trump pretende brutalizar a Venezuela, ao mesmo tempo em que produz um fluxo de discursos obsequiosos sobre o amor dos Estados Unidos pela democracia e os direitos humanos. Combinar esses dois fatores – a brutalidade e a magnanimidade – é a principal competência de Abrams.

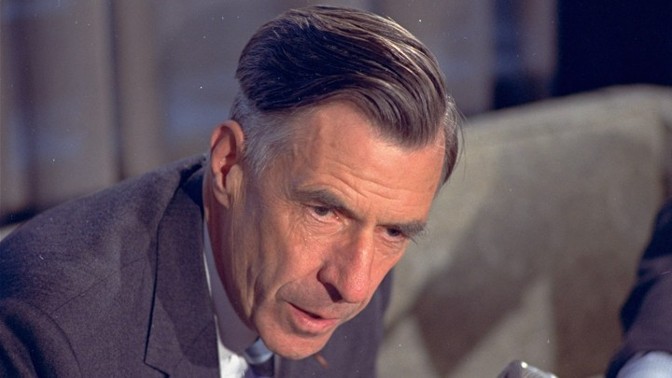

Anteriormente, Abrams serviu em uma infinidade de funções nos governos de Ronald Reagan e George W. Bush, muitas vezes com títulos declarando foco na moralidade. Primeiro, foi secretário de Estado adjunto para assuntos de organização internacional (em 1981); depois, o cargo de “direitos humanos” do departamento de Estado mencionado acima (de 1981 a 1985); secretário de Estado adjunto para assuntos interamericanos (de 1985 a 1989); diretor-sênior de democracia, direitos humanos e operações internacionais do Conselho de Segurança Nacional (de 2001 a 2005); e, finalmente, consultor adjunto de segurança nacional de Bush para a estratégia da democracia global (de 2005 a 2009).

Nessas posições, Abrams participou de muitos dos atos mais sinistros da política externa norte-americana dos últimos 40 anos, sempre proclamando o quanto se importava com os estrangeiros que ele e seus amigos estavam assassinando. Em retrospecto, é inquietante ver como Abrams quase sempre esteve presente quando as ações dos EUA eram mais sórdidas.

Abrams, graduado do Harvard College e da Harvard Law School, juntou-se à administração Reagan em 1981, aos 33 anos. Logo recebeu uma promoção devido a um golpe de sorte: Reagan queria nomear Ernest Lefever como secretário de Estado adjunto para os direitos humanos e assuntos humanitários, mas a nomeação de Lefever encalhou quando dois de seus irmãos revelaram que ele acreditava que os afro-americanos eram “inferiores, intelectualmente falando”. Um Reagan decepcionado foi forçado a recorrer a Abrams como segunda opção.

Uma preocupação central da administração Reagan na época era a América Central – em particular, as quatro nações adjacentes de Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras e Nicarágua. Todas haviam sido dominadas desde a sua fundação por minúsculas elites brancas e cruéis, com um século de ajuda das intervenções dos EUA. Em cada um desses países, as famílias dominantes viam os outros habitantes de sua sociedade como animais de forma humana, que podiam ser usados ou mortos, conforme necessário.

Porém, pouco antes da posse de Reagan, Anastasio Somoza, o ditador da Nicarágua e aliado dos EUA, foi derrubado por uma revolução socialista. Os reaganistas viram isso racionalmente como uma ameaça aos governos dos vizinhos da Nicarágua. Todos os países tinham grandes populações que, da mesma forma, não gostavam de trabalhar nas plantações de café ou de ver os filhos morrerem de doenças facilmente tratáveis. Alguns pegariam em armas e alguns simplesmente tentariam manter a cabeça baixa, mas todos, do ponto de vista dos guerreiros frios da Casa Branca, eram provavelmente “comunistas” recebendo ordens de Moscou. Eles precisavam aprender uma lição.

Foto: Marvin Recinos/AFP/Getty Images

O extermínio de El Mozote foi apenas uma gota no rio do que aconteceu em El Salvador durante os anos 1980. Cerca de 75 mil salvadorenhos morreram durante o que é chamado de “guerra civil”, embora quase todos os assassinatos tenham sido perpetrados pelo governo e seus esquadrões da morte.

Os números por si só não contam a história toda. El Salvador é um país pequeno, do tamanho do estado norte-americano de Nova Jersey. O número equivalente de mortes nos EUA seria de quase 5 milhões. Além disso, o regime salvadorenho continuamente se engajou em atos de barbárie tão hediondos que não há equivalente contemporâneo, exceto talvez o ISIS. Em uma ocasião, um padre católico relatou que uma camponesa deixou brevemente seus três filhos pequenos aos cuidados de suas mãe e irmã. Quando voltou, descobriu que todos os cinco haviam sido decapitados pela guarda nacional salvadorenha. Seus corpos estavam sentados ao redor de uma mesa, com as mãos postas nas cabeças diante deles, “como se cada corpo estivesse acariciando a própria cabeça”. A mão de um, uma criança pequena, aparentemente continuava escorregando da cabecinha, de modo que havia sido pregada nela. No centro da mesa, havia uma grande tigela cheia de sangue.

A crítica da política dos EUA na época não estava confinada à esquerda. Durante esse período, Charles Maechling Jr., que havia liderado o planejamento do departamento de contra-insurgência durante a década de 1960, escreveu no Los Angeles Times que os EUA estavam apoiando “oligarquias semelhantes à máfia” em El Salvador e em outros lugares e eram diretamente cúmplices em “métodos dos esquadrões de extermínio de Heinrich Himmler”.

Abrams foi um dos arquitetos da política do governo Reagan de apoio total ao governo salvadorenho. Ele não tinha escrúpulos em relação a nada disso nem piedade de quem escapasse do matadouro salvadorenho. Em 1984, soando exatamente como os funcionários de Trump hoje, Abrams explicou que os salvadorenhos que estavam nos EUA ilegalmente não deveriam receber nenhum tipo de status especial. “Alguns grupos argumentam que imigrantes ilegais que são enviados de volta a El Salvador enfrentam perseguição e muitas vezes a morte”, ele disse à Câmara dos Deputados. “Obviamente, não acreditamos nessas alegações, ou não deportaríamos essas pessoas.”

Mesmo fora do cargo, 10 anos após o massacre de El Mozote, Abrams expressou dúvidas de que algo desagradável houvesse ocorrido lá. Em 1993, quando uma comissão da verdade das Nações Unidas descobriu que 95% dos atos de violência ocorridos em El Salvador desde 1980 haviam sido cometidos por amigos de Abrams no governo salvadorenho, ele chamou o que ele e seus colegas no governo Reagan haviam feito de uma “realização fabulosa”.

A Fundação de Antropologia Forense da Guatemala examina sacolas de fotografias soltas dos arquivos da polícia nacional em 27 de julho de 2006, estudando as atrocidades cometidas pela polícia e os assassinatos cometidos durante os 30 anos de guerra civil na Guatemala.

Foto: Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post/Getty Images

A situação na Guatemala durante os anos 1980 era praticamente a mesma, assim como as ações de Abrams. Depois que os EUA arquitetaram a derrubada do presidente democraticamente eleito da Guatemala em 1954, o país havia sucumbido a um pesadelo em torno de ditaduras militares. Entre 1960 e 1996, em outra “guerra civil”, 200 mil guatemaltecos foram mortos – o equivalente a talvez 8 milhões de pessoas nos Estados Unidos. Uma comissão da ONU descobriu depois que o estado guatemalteco foi responsável por 93% das violações dos direitos humanos.

Efraín Ríos Montt, que serviu como presidente da Guatemala no início dos anos 1980, foi considerado culpado em 2013 pelo sistema de justiça da própria Guatemala de cometer genocídio contra os indígenas maias do país. Durante a administração de Ríos Montt, Abrams pediu o levantamento de um embargo às remessas de armas dos EUA para a Guatemala, alegando que Ríos Montt havia “trazido progresso considerável”. Os EUA tiveram de apoiar o governo guatemalteco, argumentou Abrams, porque “se assumirmos a atitude de ‘não nos procurem até estarem perfeitos, vamos nos afastar desse problema até que a Guatemala tenha um registro de direitos humanos perfeito’, e deixaremos na mão as pessoas que estão tentando progredir”. Um exemplo das pessoas que estavam fazendo um esforço honesto, segundo Abrams, era Ríos Montt. Graças a Ríos Montt, “houve uma tremenda mudança, especialmente na atitude do governo em relação à população indiana”. (A condenação de Ríos Montt foi mais tarde anulada pela mais alta corte civil da Guatemala, e ele morreu antes que um novo julgamento pudesse terminar.)

NicaráguaAbrams se tornaria mais conhecido por seu envolvimento entusiasmado com o esforço do governo Reagan para derrubar o revolucionário governo sandinista da Nicarágua. Ele defendeu a invasão total da Nicarágua em 1983, imediatamente após o bem-sucedido ataque dos Estados Unidos à pequena nação insular de Granada. Quando o Congresso cortou fundos para os Contras, força guerrilheira antissandinista criada pelos Estados Unidos, Abrams conseguiu persuadir o sultão de Brunei a desembolsar US$ 10 milhões pela causa. Infelizmente, Abrams, agindo sob o codinome “Kenilworth”, forneceu ao sultão o número errado da conta bancária na Suíça, de modo que o dinheiro foi transferido para um beneficiário sortudo aleatório.

Abrams foi questionado pelo Congresso sobre suas atividades relacionadas aos contras e mentiu abundantemente. Mais tarde, ele se declarou culpado de duas acusações de retenção de informações. Uma era sobre o sultão e seu dinheiro, e outra, sobre o conhecimento de Abrams de um avião C-123 de reabastecimento dos contras que havia sido abatido em 1986. Em uma bela rima histórica com sua nova função na administração Trump, Abrams já havia tentado obter dois C-123 para os contras dos militares da Venezuela.

Abrams recebeu uma sentença de 100 horas de prestação de serviço comunitário e considerou todo o caso como uma injustiça de proporções cósmicas. Logo escreveu um livro em que descreveu seu monólogo interior sobre seus acusadores, que dizia: “Seus desgraçados miseráveis e imundos, seus sanguessugas!” Mais tarde, ele foi perdoado pelo presidente George H. W. Bush na saída dele após perder a eleição de 1992.

PanamáEmbora isso esteja esquecido agora, antes dos Estados Unidos invadirem o Panamá para derrubar Manuel Noriega em 1989, este era um aliado próximo dos EUA – apesar de a administração Reagan saber que ele era um traficante de drogas em larga escala.

Em 1985, Hugo Spadafora, uma figura popular no Panamá e seu ex-vice-ministro da saúde, acreditava ter obtido provas do envolvimento de Noriega no tráfico de cocaína. Ele estava em um ônibus a caminho da Cidade do Panamá para torná-las públicas quando foi capturado por capangas de Noriega.

De acordo com o livro “Overthrow” (Derrubada), do ex-correspondente do New York Times, Stephen Kinzer, a inteligência dos EUA pegou Noriega dando aos seus subalternos a permissão para derrubar Spadafora como “um cão raivoso”. Spadafora foi torturado durante uma longa noite e teve a cabeça serrada enquanto ainda estava vivo. Quando o corpo foi encontrado, o estômago de Spadafora estava cheio de sangue que ele engoliu.

Foi algo tão terrível que chamou a atenção das pessoas. Mas Abrams saltou em defesa de Noriega, impedindo o embaixador dos EUA no Panamá de aumentar a pressão sobre o líder panamenho. Quando o irmão de Spadafora convenceu o hiperconservador senador do Partido Republicano da Carolina do Norte, Jesse Helms, a realizar audiências no Panamá, Abrams disse a Helms que Noriega estava “sendo realmente útil para nós” e “não era um problema tão grande assim. … Os panamenhos prometeram que vão nos ajudar com os contras. Se você fizer as audiências, isso os alienará”.

… E isso não é tudoAbrams também se envolveu em conduta ilegal por nenhuma razão discernível, talvez apenas para ficar em forma. Em 1986, uma jornalista colombiana chamada Patricia Lara foi convidada aos EUA para participar de um jantar de homenagem a escritores que haviam promovido “o entendimento interamericano e a liberdade de informação”. Quando Lara chegou ao aeroporto Kennedy, em Nova York, foi levada sob custódia e depois colocada em um avião de volta para casa. Logo depois, Abrams apareceu no programa “60 minutos” para alegar que Lara era membro dos “comitês dirigentes” do M-19, um movimento guerrilheiro colombiano. Ainda segundo Abrams, ela era também “uma ligação ativa” entre o M-19 “e a polícia secreta cubana”.

Dada a frequente violência paramilitar de direita contra os repórteres colombianos, isso representou um alvo marcado nas costas de Lara. Não houve evidência de que as afirmações de Abrams fossem verdadeiras – o próprio governo conservador da Colômbia as negou – e nenhuma apareceu desde então.

Os enganos sem fim e desavergonhados de Abrams desgastaram repórteres americanos. “Eles diziam que preto era branco”, explicou mais tarde Joanne Omang, do Washington Post, sobre Abrams e seu colega na Casa Branca, Robert McFarlane. “Embora tivesse usado todos os meus recursos profissionais, enganei meus leitores.” Omang ficou tão exausta com a experiência, que largou o emprego tentando descrever o mundo real para tentar escrever ficção.

Após a condenação, Abrams passou a ser visto como um problema que não podia retornar ao governo. Isso o subestimou. O almirante William J. Crowe Jr., ex-comandante dos chefes de estado maior conjunto, envolveu-se ferozmente com Abrams em 1989 sobre a política dos EUA quanto a Noriega, depois que ficou claro que ele era mais problemático do que era possível aceitar. Crowe se opôs fortemente à brilhante ideia que Abrams havia apresentado: de que os Estados Unidos deveriam estabelecer um governo no exílio em solo panamenho, o que exigiria a guarda de milhares de soldados norte-americanos. Foi algo profundamente estúpido, Crowe disse, mas isso não importava. Prescientemente, Crowe emitiu um aviso sobre Abrams: “Esta cobra é difícil de matar”.

Foto: Dennis Brack-Pool/Getty Images

Para a surpresa dos iniciados mais ingênuos de Washington, Abrams estava de volta à ativa logo depois de George W. Bush entrar na Casa Branca. Como poderia ser difícil obter aprovação do Senado para alguém que havia enganado o Congresso, Bush o colocou em um cargo no Conselho de Segurança Nacional – onde não era necessária qualquer aprovação do Legislativo. Assim como ocorrera 20 anos antes, Abrams recebeu um portfólio envolvendo “democracia” e “direitos humanos”.

VenezuelaNo início de 2002, o presidente da Venezuela, Hugo Chávez, havia se tornado profundamente irritante à Casa Branca de Bush, que estava repleta de veteranos das batalhas dos anos 1980. Naquele mês de abril, de repente, do nada, Chávez foi expulso do poder em um golpe. Se e como os EUA estavam envolvidos ainda não é conhecido, e provavelmente não será por décadas até que os documentos relevantes sejam desclassificados. Mas, com base nos cem anos anteriores, seria surpreendente que os Estados Unidos não tenham desempenhado nenhum papel nos bastidores. Pelo que se sabe, na época, o London Observer relatou que “a figura crucial em torno do golpe foi Abrams”, e ele “deu um aceno” aos conspiradores. De qualquer modo, Chávez teve apoio popular suficiente para conseguir se reagrupar e voltar ao cargo em questão de dias.

IrãAparentemente, Abrams desempenhou um papel importante no silenciamento de uma proposta de paz do Irã em 2003, logo após a invasão do Iraque pelos EUA. O plano chegou por fax, e deveria ter ido para Abrams e depois para Condoleezza Rice, na época conselheira de segurança nacional de Bush. Em vez disso, de alguma forma, a proposta nunca chegou à mesa de Rice. Quando perguntado a respeito disso mais tarde, o porta-voz de Abrams respondeu que ele “não tinha lembrança de qualquer fax do tipo”. (Abrams, como tantas pessoas que prosperam no nível mais alto da política, tem uma memória terrível para qualquer coisa política. Em 1984, ele disse a Ted Koppel que não conseguia se lembrar se os EUA haviam investigado relatos de massacres em El Salvador. Em 1986, quando perguntado pelo comitê de inteligência do Senado se havia discutido a arrecadação de fundos para os contras com qualquer pessoa da equipe do Conselho de Segurança Nacional, também não conseguiu se lembrar.)

Israel e PalestinaAbrams também esteve no centro de outra tentativa de frustrar o resultado de uma eleição democrática, em 2006. Bush havia pressionado por eleições legislativas na Cisjordânia e em Gaza para dar à Fatah, a organização palestina altamente corrupta liderada pelo sucessor de Yasser Arafat, Mahmoud Abbas, uma legitimidade muito necessária. Para surpresa de todos, o rival do Fatah, o Hamas, ganhou, dando-lhe o direito de formar um governo.

Esse desagradável surto de democracia não foi aceitável para o governo Bush, em especial para Rice e Abrams. Eles elaboraram um plano para formar uma milícia da Fatah para assumir a Faixa de Gaza e esmagar o Hamas em seu território. Como relatado pela Vanity Fair, isso envolveu muita tortura e execuções. Mas o Hamas combateu o Fatah com sua própria ultraviolência. David Wurmser, neoconservador que trabalhava para Dick Cheney na época, disse à Vanity Fair: “Parece-me que o que aconteceu não foi tanto um golpe do Hamas, mas uma tentativa de golpe do Fatah que foi esvaziada antes que pudesse acontecer”. No entanto, desde então, esses eventos foram virados de cabeça para baixo pela mídia dos EUA, com o Hamas sendo apresentado como o agressor.

Embora o plano dos EUA não tenha sido um sucesso total, também não foi um fracasso total da perspectiva dos Estados Unidos e de Israel. A guerra civil palestina dividiu a Cisjordânia e Gaza em duas entidades, com governos rivais em ambos. Nos últimos 13 anos, houve poucos sinais da unidade política necessária para que os palestinos tivessem uma vida digna para si mesmos.

Abrams então deixou o cargo com a saída de Bush. Mas agora está de volta para uma terceira rodada pelos corredores do poder – com os mesmos tipos de esquemas que executou nas duas primeiras vezes.

Recapitulando a vida de mentiras e crueldade de Abrams, é difícil imaginar o que ele poderia dizer para justificá-la. Mas ele tem uma defesa para tudo o que fez – e é uma boa defesa.

The year was 1995. A young Elliott Abrams taught us how to laugh. Maniacally. When Allan Nairn brought up his involvement in the mass murder and torture of indigenous people in Guatemala. pic.twitter.com/N2nfDQAUrf

— Allen Haim (@senor_pez) 25 de janeiro de 2019

O ano era 1995. Um jovem Elliott Abrams nos ensinou como rir. Como um maníaco. Quando Allan Nairn falou de seu envolvimento no assassinato e tortura massivas dos povos indígenas na Guatemala.

Em 1995, Abrams apareceu no “The Charlie Rose Show” com Allan Nairn, um dos repórteres americanos mais versados sobre a política externa dos EUA. Nairn observou que George H. W. Bush já havia discutido colocar Saddam Hussein em julgamento por crimes contra a humanidade. Essa era uma boa ideia, disse Nairn, mas “se você é sério, precisa ser imparcial” – o que significaria também processar funcionários como Abrams.

Abrams riu diante do absurdo de tal conceito. Isso exigiria, disse ele, “colocar todos os funcionários americanos que venceram a Guerra Fria no banco dos réus”.

Abrams estava em grande parte certo. A realidade angustiante é que Abrams não é um bandido isolado, mas um respeitado e honrado membro da centro-direita do establishment da política externa dos EUA. Seus primeiros empregos antes de ingressar no governo Reagan foram trabalhar para dois senadores democratas, Henry Jackson e Daniel Moynihan. Ele era um membro sênior do conselho centrista de relações exteriores. Ele é membro da comissão dos EUA sobre liberdade religiosa internacional e agora está no conselho do National Endowment for Democracy. Ele deu aulas à próxima geração de funcionários de política externa na Escola de Serviço Exterior da Universidade de Georgetown. Ele não enganou Reagan e George W. Bush de alguma forma – eles queriam exatamente o que Abrams fornecia.

Portanto, não importam os detalhes macabros da carreira de Abrams, o importante a ser lembrado – conforme a águia americana aperta suas garras afiadas em torno de outro país da América Latina – é que Abrams não é tão excepcional assim. Ele é sobretudo uma engrenagem em uma máquina. É a máquina que é o problema, não suas partes mal intencionadas.

Tradução: Cássia Zanon

The post Escolhido de Trump para levar “democracia” à Venezuela passou a vida esmagando a democracia appeared first on The Intercept.

Eight years ago this month, the wave of pro-democracy protests that came to be known as the Arab Spring reached Bahrain, where a brief flowering of dissent against the Gulf monarchy that hosts the U.S. Navy’s 5th Fleet was stifled in a bloody crackdown, backed by troops from neighboring Saudi Arabia.

Dozens of protesters, drawn largely from the country’s Shiite Muslim majority, were gunned down in broad daylight by security forces, including marchers with their hands in the air, chanting, “Peaceful! Peaceful!” Thousands of political prisoners have been detained and tortured — among them, stars of the national soccer team — and the country’s leading human rights activist has been jailed repeatedly for tweeting.

Despite such outrages, Bahrain’s royal family, bolstered by the presence of the U.S. Navy — and subjected only to mild criticism by the Obama Administration, and none by the Trump Administration — has been able to act against pro-democracy activists with relative impunity, in part by framing dissent against the Sunni Muslim monarchy as some kind of plot by Iran, the Shiite-led power across the Persian Gulf.

One of the few times Bahrain’s rights record has proven costly to the ruling al-Khalifa family was in 2016, when a leading member, Sheikh Salman bin Ebrahim al-Khalifa, failed to win an election to be the head of the world soccer governing body, FIFA, following a campaign by dissidents to draw attention to his failure to protect Bahraini soccer players who were arrested and tortured for taking part in the demonstrations.

Among those who voiced public criticism of Sheikh Salman ahead of the FIFA election was Hakeem al-Araibi, a former player on Bahrain’s national soccer team who said that he had been threatened and tortured for speaking out, and was forced to flee the country for Australia after being accused of taking part in an attack on a police station. Araibi called that charge absurd, since he had been on the soccer field at the time, playing in a nationally televised match, but he was convicted in absentia nonetheless and sentenced to 10 years in prison. That sentence seemed to confirm that his fears of persecution by Bahrain’s government were legitimate, and he was granted asylum by the authorities in Australia, where he signed with a semiprofessional team in Melbourne and set about rebuilding his life.

Asked in 2016 to comment on Sheikh Salman’s candidacy to lead FIFA, Araibi told the New York Times that the royal had failed to respond to a request from his sister to intervene or stop his torture. “They blindfolded me,” he recalled. “They held me really tight, and one started to beat my legs really hard, saying: ‘You will not play soccer again. We will destroy your future.'”

In November, Araibi discovered the doggedness with which Bahrain continues to pursue dissidents when he flew from Australia to Thailand with his wife for a delayed honeymoon, and, despite having been assured by Australian authorities that his status as a refugee would protect him, he was detained on arrival by Thai police acting on an Interpol red notice issued at Bahrain’s request. He has been in jail in Bangkok, fighting extradition to Bahrain, ever since.

“If Hakeem is extradited to #Bahrain, he is at great risk of facing torture & unlawful imprisonment. His extradition would constitute to refoulement and therefore would be a clear breach of international law.” @BirdBahrain_ https://t.co/11d7a410ck pic.twitter.com/rUVUBrpN1y

— Sayed Ahmed AlWadaei (@SAlwadaei) December 3, 2018

On Friday, Thailand’s attorney general ignored requests from Australia — and pleas from the secretary general of FIFA, as well as senior officials at the United Nations and the International Olympic Committee — to stop the extradition process and referred the matter to court.

The fact that the arrest warrant for Araibi was sent to Thai authorities only after the soccer player had purchased his plane tickets suggests that Bahrain was keeping close tabs on him. In an interview with The Guardian last week, Araibi said that he was convinced that his arrest was nothing more than revenge for his criticism of Sheikh Salman, who is currently standing for re-election as the head of the Asian Football Confederation. “Bahrain wants me back to punish me because I talked to the media in 2016 about the terrible human rights and about how Sheikh Salman is a very bad man who discriminates against Shia Muslims,” Araibi said from Bangkok Remand Prison. “I am so scared of being sent back to Bahrain, so scared because 100 percent they will arrest me, they will torture me again, possibly they will kill me.”

Nadthasiri Bergman, Araibi’s lawyer, promised to appeal an extradition decision and urged the player’s supporters to raise public awareness of his plight.

“For 7 years, not a day went by that I did not hear my wife's voice. Now I'm in jail for a crime I didn't commit. She is out there. Alone. It breaks my heart not to know when I will get to see her or hear her voice again. Please fight for me.” A message from Hakeem. #SaveHakeeem pic.twitter.com/uhYkGdiqnC

— Nadthasiri Bergman (@Nat_Bergman) January 29, 2019

The post Eight Years Later, America’s Ally Bahrain Is Still Hunting Down Arab Spring Protesters appeared first on The Intercept.

Backed by millions in spending by a handful of billionaires, the charter school movement has been on the march for years, nowhere more so than in California. As its momentum has grown, traditional public education has been on the retreat throughout the state, resulting in school closures, overburdened teachers, and fiscal crises for school districts.

Then came the Los Angeles teachers strike.

This week, the Los Angeles Board of Education passed a resolution asking the state to impose an eight- to 10-month moratorium on new charter schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District. The measure, which was among the demands on the bargaining table during the strike, was unprecedented for the school district and even more surprising given the school board’s pro-charter slant. The vote demonstrated the breadth of the victory achieved by the strike, which halted the charter school movement’s relentless advance in the second-biggest school district in the country.

Now, the front line of the fight over public schools is shifting to Oakland, where today, teachers are casting ballots on whether to strike as soon as mid-February. As in LA, the issues on the bargaining table in Oakland include higher teacher salaries, smaller class sizes, and more support staff in schools. And, also as in LA, looming in the background is a years-long fight between billionaires who aim to eliminate traditional, democratically controlled public schools and teachers who wish to preserve them.

Billionaires vs. TeachersThe Oakland Unified School District is in a fiscal crisis. The school board has halted construction projects and is planning to cut over 100 central administrative jobs, impose across-the-board cuts to all of its schools, and close two dozen schools over five years in a desperate scramble to forestall a $30 million budget deficit for the 2019-20 school year.

The impact of the deficit at the classroom level is most apparent in the Oakland school district’s sky-high teacher turnover rate. Oakland teachers are among the lowest-paid in the Bay Area, and 1 in 5 of them leave the district annually, compared to just over 1 in 10 statewide. “We’re grinding them out,” said Ismael Armendariz, a 32-year-old special education instructor, of the churn rate for teachers in the district. Armendariz, who is currently on leave to do union work but is still employed by the school district, makes $57,000 a year in one of the most expensive metropolitan areas in the world. “I live paycheck to paycheck,” he said.

A major contributor to the crisis is the rapid and uncontrolled expansion of charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately run.

In recent years, the charter school industry and its supporters have dumped huge sums of money into elections in California in an aggressive bid to expand its presence in public school districts throughout the state. Last year, a record $50 million was spent in the race for state superintendent of public instruction, two-thirds of it on behalf of the pro-charter candidate. A state legislative race in the East Bay drew $1.4 million in spending from outside groups, much of it from the charter school industry. In 2017, the Los Angeles school board race became the most expensive in U.S. history, at a combined $15 million, with close to $10 million of it coming from the charter side.

But Oakland in particular seems to hold special significance for charter school boosters. The city has drawn a deluge of money from pro-charter billionaires that is rare to see in municipal elections. Last year, Michael Bloomberg donated $120,000 to an independent expenditure committee connected with GO Public Schools, a nonprofit organization that organizes and advocates on behalf of charter school expansion, which went on to drop more than $150,000 on a single 2018 Oakland school board race.

The investments have paid dividends. Out of the seven seats on the Oakland school district’s board, five are occupied by GO Public Schools-endorsed candidates. “Oakland is one of the cities where the charter school industry thinks maybe they can flip the whole district,” said University of Oregon political economist Gordon Lafer. GO Public Schools did not return a request for comment.

It’s extraordinarily easy to open a charter school in California. “Anybody minimally legally and financially compliant cannot be stopped from opening a school,” said Lafer, who has studied the growth of charters in the state. By law, school districts cannot deny a petition to open a charter school unless its educational program is unsound or it is “demonstrably likely” to fail at its educational mission.

According to Lafer’s research, the proliferation of charter schools in Oakland costs the school district $57.3 million per year, yet the district cannot take into account the impact a new charter will have on the finances of existing schools when deciding on an application.

Charter schools directly compete with traditional public schools; they fill their classrooms by drawing students away from district-run schools. In California, schools are funded on a per-pupil basis. That means that when a student leaves a school, her apportionment of funding goes with her, costing the school district money. The district also saves the expense of educating that student, but given the fixed costs of running a school, Lafer’s research shows, the amount of money lost to the school district always outpaces the amount saved.

Compounding this dynamic is the requirement that traditional schools take in all students who come their way, while charters have no such obligation. Through the enrollment process, charters often filter out students whose education would require more resources, including special needs students, homeless youth, students learning English as a second language, and those who recently arrived as refugees. “They recruit kids and they say, ‘We want you to write an essay; we want your parents to write an essay; we want your parents to volunteer in school,’” Lafer said, which has the effect of pushing away less self-motivated students and children of parents who are, by habit or circumstance, less focused on their children’s education. “You have a system where the neediest and most expensive kids to educate are concentrated in traditional public schools.”

The disparity is particularly pronounced with special needs students. In California, funding for special education is based on the overall student population, not on the percentage of special needs students a school enrolls. By enrolling fewer special needs students, charter schools are able to receive funding for services they do not provide, while public schools’ efforts are underfunded.

As a special education instructor, Armendariz experienced the consequences of this shortfall. “We wouldn’t get the support we needed,” he said. “When we reached out [to the district], we were at the bottom of the list. Mental health support, slots with counselors — it was hard to get people with experience working with kids with disabilities.”

“All of those burdens fall on our district, because we have a moral and a legal obligation to serve them,” Armendariz said. The system, he added, seems “designed to fail.”

At a meeting for parents about a possible upcoming strike, the Oakland Education Association distributed signs to community members to show their support for public school teachers.

Photo: Leighton Akio Woodhouse for The Intercept

The growth of Oakland charter schools has been so explosive it has led to a fear among charter school operators that in their competition to recruit new students, charters are cannibalizing not just traditional schools, but each other. That concern is one impetus for an effort by charter school advocates to establish a new model of overseeing the district, called the “portfolio model,” under which the school board is transformed from a governmental oversight body into something more like an investment portfolio manager. Rather than determine rules and regulations and allocate budgets based on need, under the portfolio model, the board evaluates school performance and invests and divests from them accordingly, like publicly traded stocks.

The model could rationalize and streamline the explosion of charter schools in Oakland and bring a measure of order to a largely unregulated market. It could also lead to further expansion of the charter school sector at the expense of traditional public schools, weaken the city’s teachers union, and undermine democratic control of the city’s schools.

That’s what happened in New Orleans, where after Hurricane Katrina, the state took over the public school system and converted it almost entirely into nonunion charter schools. Last year, control was handed back to a locally elected school board, but unelected staffs of charter management organizations maintained power over financing, personnel, and pedagogy.

In 2014, when the district was still under state control, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings attributed what he believed to be the success of New Orleans charter schools to the fact that “they don’t have an elected school board.” He described school boards as an impediment to long-term education planning and charter schools as a vehicle to “evolve America” beyond them.

Elected school boards — where advocates for district schools, including teachers unions, can exercise political power — have traditionally resisted the expansion of charter school chains, whose growth can benefit tech industry moguls like Hastings. Charter management organizations such as the Knowledge is Power Program, whose board Hastings sits on, are known for “blended learning,” an approach to teaching that puts a heavy emphasis on integrating screens and internet into classroom instruction. This pedagogical method has helped fuel a booming $43 billion market in educational technology, which tech giants like Google, Apple, and Microsoft have battled to dominate, and in which Mark Zuckerberg’s foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, has invested heavily, with mixed results.

Hastings has spent eye-popping amounts to move California school boards in his direction, including $7 million on LA’s 2017 school board race, which resulted in the city’s first ever pro-charter majority. The portfolio model would solidify these gains by permanently transferring school boards’ power over key areas of decision making to privately held, nonprofit charter management organizations — essentially deregulating charter schools. It is the vision behind GO Public Schools’s Oakland initiative, which has proven divisive even among charter school advocates and has been excoriated by defenders of district schools. Keith Brown, the president of Oakland’s teachers union, said the plan would “put the nail in the coffin for democratic control of our public schools.”

Even without the portfolio model, Oakland public school teachers are faced with a school board that largely favors the partial privatization of public education, which has put their district in chronic fiscal crisis, bled their schools of resources, and overburdened them with the most expensive students to teach. With the conventional political process effectively controlled by pro-charter billionaires, teachers are turning to their most direct and foundational source of power: the ability to withhold their labor.

“We have exhausted all of our options,” said Armendariz. “Teachers feel that the only way we’re going to make any change is to take the fight to the privatizers.”

Correction: February 1, 2019, 3:05 p.m. ET

A previous version of this article misstated the size of the Los Angeles Unified School District and misstated Ismael Armendariz’s employment status and salary. It has been corrected.

The post “We Have Exhausted All Our Options”: Oakland Teachers May Be the Next to Strike appeared first on The Intercept.

A new website exposes the extent to which Apple cooperates with Chinese government internet censorship, blocking access to Western news sources, information about human rights and religious freedoms, and privacy-enhancing apps that would circumvent the country’s pervasive online surveillance regime.

The new site, AppleCensorship.com, allows users to check which apps are not accessible to people in China through Apple’s app store, indicating those that have been banned. It was created by researchers at GreatFire.org, an organization that monitors Chinese government internet censorship.

In late 2017, Apple admitted to U.S. senators that it had removed from its app store in China more than 600 “virtual private network” apps that allow users to evade censorship and online spying. But the company never disclosed which specific apps it removed — nor did it reveal other services it had pulled from its app store at the behest of China’s authoritarian government.

In addition to the hundreds of VPN apps, Apple is currently preventing its users in China from downloading apps from news organizations, including the New York Times, Radio Free Asia, Tibetan News, and Voice of Tibet. It is also blocking censorship circumvention tools like Tor and Psiphon; Google’s search app and Google Earth; an app called Bitter Winter, which provides information about human rights and religious freedoms in China; and an app operated by the Central Tibetan Authority, which provides information about Tibetan human rights and social issues.

Some bans – such as those of certain VPN apps and the Times – have received media coverage in the past, but many never generate news headlines. Charlie Smith, a co-founder of GreatFire.org, told The Intercept that the group was motivated to launch the website because “Apple provides little transparency into what it censors in its app store. Most developers find out their app has been censored after they see a drop in China traffic and try to figure out if there is a problem. We wanted to bring transparency to what they are censoring.”

“We wanted to bring transparency to what they are censoring.”

Smith, who said that the website was still in a beta phase of early development, added that until now, it was not easy to check exactly which apps Apple had removed from its app stores in different parts of the world. For example, he said, “now we can see that the top 100 VPN apps in the U.S. app store are all not available in the China app store.”

The site is not able to distinguish between apps taken down due to requests from the Chinese government because they violate legal limits on free expression versus those removed because they violate other laws, such as those regulating gambling. However, it is possible to determine from the content of each app – and whether it continues to be available in the U.S. or elsewhere – the likely reason for its removal.

Radio Free Asia, for instance, has been subject to censorship for decades in China. The Washington, D.C.-based organization, which is funded by the U.S. government, regularly reports on human rights abuses in China and has had its broadcasts jammed and blocked in the country since the late 1990s. That censorship has also extended to the internet – now with the support of Apple.

Rohit Mahajan, a spokesman for Radio Free Asia, told The Intercept that Apple had informed the organization in December last year that one of its apps was removed from the app store in China because it did not meet “legal requirements” there. “There was no option to appeal, as far as we could discern,” said Mahajan.

Libby Liu, Radio Free Asia’s president, added that “shutting down avenues for credible, outside news organizations is a loss – not just for us, but for the millions who rely on our reports and updates for a different picture than what’s presented in state-controlled media. I would hope that Western companies would be committed to Western values when it comes to making decisions that could impact that access.”

An Apple spokesperson declined to address removals of specific apps from China, but pointed to the company’s app store review guidelines, which state: “Apps must comply with all legal requirements in any location where you make them available.” The spokesperson said that Apple, in its next transparency report, is planning to release information on government requests to remove apps from its app store.

The Chinese government expects Western companies to make concessions before it permits them to gain access to the country’s lucrative market of more than 800 million internet users. The concessions include compliance with the ruling Communist Party’s sweeping censorship and surveillance regime. In recent years, the Chinese state has beefed up its repressive powers. It has introduced a new “data localization” law, for instance, which forces all internet and communication companies to store Chinese users’ data on the country’s mainland — making it more accessible to Chinese authorities.

In accordance with the data localization law, Apple agreed to a deal with state-owned China Telecom to control and store Chinese users’ iCloud data. Apple claims that it retains control of the encryption keys to the data, ensuring that people’s photographs and other private information cannot be accessed by the Chinese state. However, human rights groups remain concerned. Amnesty International has previously stated, “By handing over its China iCloud service to a local company without sufficient safeguards, the Chinese authorities now have potentially unfettered access to all Apple’s Chinese customers’ iCloud data. Apple knows it, yet has not warned its customers in China of the risks.”

Apple CEO Tim Cook has presented himself as a defender of users’ privacy. During a speech in October last year, Cook declared, “We at Apple believe that privacy is a fundamental human right.” It is unclear how Cook reconciles that sentiment with Apple’s removal of privacy-enhancing software from its app store in China, which helps ensure that the country’s government can continue to monitor its citizens and crack down on opponents. Cook appears to have viewed compliance with Chinese censorship and surveillance as worthwhile compromises. “We would obviously rather not remove the apps,” he said in 2017, “but like we do in other countries we follow the law wherever we do business. … We’re hopeful that over time the restrictions we’re seeing are lessened, because innovation really requires freedom to collaborate and communicate.”

The post New Site Exposes How Apple Censors Apps in China appeared first on The Intercept.

House Energy and Commerce Democrats weren’t thrilled about the suggestion of a new select House committee on climate change, worried that its power would creep into their expansive jurisdiction. Committee leaders flexed what internal muscle they had to make sure that the committee, established at the behest of progressives behind the “Green New Deal,” was defanged, withholding subpoena power and the authority to approve new legislation.

Rep. Bobby Rush, the No. 2 Democrat on the Energy and Commerce Committee, told The Intercept that he was pleased to see the end of a “smash and grab” that’s pushed the committee to cede “too much of our jurisdiction over the years.”

“The grab is over, as far as I’m concerned, in terms of Energy and Commerce, this smash and grab that’s been going on for too long in this Congress,” he told The Intercept in an interview.

“We’re gonna return to regular order as we have exercised it in the past, and we stand on it now. You know, we’re not ceding any of the Energy and Commerce jurisdiction. I’m not in favor of not one measure, not one iota of Energy and Commerce’s jurisdiction to be ceded to other committees.”

Asked what he planned to do with that power, Rush said, “We’re gonna do what we’ve always done. Legislate, deliberate, legislate, move bills to the floor. And we’re going to continue to work hard on behalf of the American people.”

But while Chair Frank Pallone said he understands and shares concerns “about the need for transformational action” laid out in the Green New Deal, he added in a statement to The Intercept that he wants to prioritize “actions we can take this year that will make a difference now.”

That doesn’t square with the Green New Deal’s 10-year plan to get to 100 percent renewable energy, which foresees drafting and organizing around transformative legislation in the next two years, and then enacting it in the beginning of a new Democratic administration. To pull that off, the advocates of the select committee argued that none of its members should take money from fossil fuel companies.

Stephen Hanlon, communications director for the Sunrise Movement, which led the occupation in the office of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, told The Intercept that walking and chewing gum was preferable. “With Trump in the White House, we’re focusing on building the public and political support to elect a Congress and president in 2020 that can make the Green New Deal law in 2021,” Hanlon said. “We certainly should take what action we can in the interim, but that is no substitute for putting forward a plan in line with the ambition the latest science says is necessary.”

Pallone argued that the fossil fuel industry dollars flowing through the committee won’t have any impact on the agenda.

The committee’s first hearing will assess the environmental and economic impacts of climate change, Pallone said, and it will be “the first of many hearings on the subject.” He pointed out the “stark difference from past Republican House majorities, which refused to hold hearings on climate change and denied that it even existed.” Asked if oil and gas executives would be called before the committee, a spokesperson told The Intercept that no decisions have been made about specific hearings or who would testify.

Pallone plans to prioritize investing in green energy infrastructure, energy efficiency, and other programs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and reversing a long list of environmental rollbacks under the Trump administration, he said, which included lifting restrictions on coal plant greenhouse gas emissions and opening parts of the Arctic to oil and gas drilling.

But when asked whether the committee would reconsider how it addresses contributions to members from the fossil fuel industry, Pallone — who does not take oil and gas money — noted his longstanding support of public campaign finance and said he believes that lawmakers should be judged instead by their record and agenda.

Asked if he thought the pledge by incoming Reps. Nanette Barragán and Darren Soto to refuse fossil fuel money would spread to other members of the committee, Rush — who receives the second least oil and gas money of the eight committee members who take it — told The Intercept that he wasn’t sure. “And that’s an individual decision among members of the committee. I would not dare try to dictate their fundraising strategies or techniques,” he said. Neither Barragán nor Soto responded to requests for comment.

Rep. Kurt Schrader, former chair of the conservative Blue Dog caucus, took the most money from the oil and gas industry last cycle at $77,500, with $75,500 coming from PACs and $2,000 from individuals. Next is incoming committee member Rep. Marc Veasey, who took a total of $63,050, including $40,500 from PACs and $22,550 from individuals. Rep. Gene Green took $24,000 from the industry, including $23,500 from PACs and $500 from individuals. Rep. Paul Tonko took $24,000 in PAC money. Rep. Mike Doyle took $18,000 from oil and gas PACs, and Rep. Peter Welch took $18,000. Rush took $13,000 in oil and gas PAC money, and Rep. G. K. Butterfield took $11,500.

Of 31 Democrats on the committee, those who signed the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge, in addition to Barragán and Soto, are Reps. Joe Kennedy of Massachusetts and Jan Schakowsky of Illinois.

Asked if Veasey would continue taking oil and gas money, his office did not answer the question but directed The Intercept to a tweet from his account announcing his support for public campaign financing, as laid out in H.R. 1. Schrader did not respond to a request for comment.

Vice Chair Yvette Clarke of New York, who has not signed the pledge but does not take oil and gas money, told The Intercept that she didn’t have a position on the issue. “I think that if that is a determination about how you vote or how you shape policy, that it’s definitely a conflict,” she said, but added that during her time in the committee minority, Democrats were unified in pushing back against bad actors. “I haven’t seen that as a major factor, as a factor at all,” she said.

Rep. Eliot Engel, also of New York, said he doesn’t take money from the industry. Asked if he thought his colleagues should join the pledge, he said he thought it was an independent decision. “I don’t take the money because I don’t agree with the philosophy, but I’m not gonna point the finger at anybody else,” he told The Intercept. He said he doesn’t think that taking oil and gas money presents a conflict of interest but that he “would love to see money get out of politics,” referencing New York City’s public campaign finance program as a model.

“Politicians making climate policy should not be taking money from the lobbyists and executives who have spent the past decades deceiving the public about the science and doing everything they can to protect their bottom lines, even when that means imperiling the entire planet,” said Hanlon, the Sunrise Movement spokesperson. “Any politician who wants the votes of young people in 2020 needs to sign the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge and back a Green New Deal. If Frank Pallone is serious about taking action on climate, he will use his chairmanship to put forward a vision for a Green New Deal in line with what science and justice demands.”

The post With Green New Deal Committee Neutered, Energy and Commerce Democrat Says “Smash and Grab” Is Over appeared first on The Intercept.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman arrives to meet with British Prime Minister Theresa May in London, England, on March 7, 2018.

Photo: Dan Kitwood /Getty Images

Last week, Saudi Arabia’s General Entertainment Authority announced 2019 as the “Year of Entertainment” in the kingdom. With a $64 billion budget granted by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the plan comes complete with a social media platform and an app — Enjoy_Saudi — and aims to “transform the Kingdom into one of the top ten international entertainment destinations.” The authority said it is negotiating contracts to bring international stars, such as Mariah Carey, Jay-Z, Trevor Noah, Chris Rock, and Seth Rogen, among others, to the kingdom.