Ser jogador de futebol. Quanta gente já não sonhou com isso?

Com 11 anos, eu levei essa ideia a sério e entrei para as categorias de base de um time de Porto Alegre. Fiquei apenas seis meses. Felizmente, minha família tinha condições financeiras que me permitiram priorizar os estudos. Depois dessa breve experiência, só voltei a pensar no assunto aos 17 anos.

Engraçado que, quando você entra nesse mundo, percebe que os sonhos vão ficando cada vez mais distantes. E, ao mesmo tempo, você está lá, lutando. As pessoas de fora veem você como uma “estrela”, como se sua vida fosse igual à dos caras que aparecem na TV. Mas a realidade é uma merda. Acham que você tem dinheiro, um carro bom, roupas de marca, sendo que às vezes nem tem travesseiro pra dormir ou cobertor para se esquentar. No caso do meu ex-treinador Emerson, que jogou nas categorias de base, o cobertor era sua toalha de banho. Ele a deixava secando de manhã cedo para se cobrir de noite. Aliás, sorte a sua se houver arroz e feijão em dia de jogo, diferente do meu amigo “Índio”, que jogou o campeonato estadual no Mato Grosso. Lá o seu almoço era um pote de bananas – e isso que ele já jogava no profissional.

Uma vez perguntei se o treino iria continuar, e o treinador respondeu, me xingando: “tu tá com medo de raio?”Fora as condições precárias, vocês acham que a gente ganha quanto por mês? Dedicamos todo nosso tempo, esforço e foco para isso, dormindo regrado, acordando cedo, dando a vida nos treinos, faça sol, chuva, calor, frio e até raio caindo – uma vez perguntei se o treino iria continuar, e o treinador respondeu, me xingando: “tu tá com medo de raio?”

Depois de nos doarmos ao máximo, longe de nossas famílias, quanto vocês acham que recebemos de remuneração? Menos de um salário mínimo. Ou às vezes nenhuma, como ocorre com meu parceiro Luquinhas, que joga na quarta divisão de Portugal. Em outros clubes, é só um vale-transporte mensal, porque, querendo ou não, os jogadores precisam ir para os treinos durante a semana. Pelo menos disso os dirigentes se dão conta.

Mas e quando não dá para reservar a grana só para o transporte? E quando você tem filhos? Quando tem que ajudar a família com o pouco que ganha? Sua mãe? Seus irmãos? Eu tenho amigos que seguem no futebol, mas já abandonaram o sonho de se tornar grandes ou de ter uma vida melhor: eles jogam apenas porque é o que lhes resta, é isso que eles têm, e pronto. É o que eles foram ensinados a fazer, é o que eles sabem fazer em um país com cada vez menos investimentos em educação pública. E essa é a única saída “limpa” e “justa” que eles encontram, para quem sabe um dia sair da pobreza. Na verdade, eles têm outro caminho a seguir, e vocês sabem de qual eu estou falando. Esse mesmo: o crime. Às vezes, alguns até conseguem conciliar os dois, tráfico e futebol.

Na segunda-feira, mesmo dia em que o alojamento do Bangu pegou fogo, um ex-companheiro de clube, que está jogando a segunda divisão do Campeonato Gaúcho, no profissional, me pediu dinheiro emprestado porque a polícia pegou a droga dele, e ele estava devendo para os donos da boca. Decidiu vender drogas para aumentar sua renda, que não é suficiente para sustentar sua mãe e seus irmãos.

Situação parecida aconteceu com meu amigo Adilio, que jogou comigo no profissional da segunda divisão do Rio de Janeiro. Ele nunca vendeu droga, nada disso. Mas, com o salário de R$ 1 mil que recebia, já ajudava a manter sua família e sua casa na favela. Só que a temporada durava apenas seis meses. No resto do ano, fechava “contrato” com o pai dele e virava pedreiro na pré-temporada. E o Léo, um dos melhores volantes do campeonato nessa mesma temporada? Lá estava ele, vendendo chá-mate na beira da praia durante as férias – quando não fazia um bico de barbeiro.

Em 2017, disputei a Copa São Paulo de Juniores pela equipe sub-20 da Chapecoense. Os clubes de cada grupo ficam no mesmo lugar durante a primeira fase. Dividimos hotel com o Nova Iguaçu, do Rio de Janeiro, e o Sampaio Corrêa, do Maranhão. Na sala de jogos, jogando pingue-pongue, um dos meninos do Nova Iguaçu perguntou quanto que a gente ganhava por mês. Eles ficaram impressionados: R$ 600, um salário do qual nós mesmos reclamávamos o tempo inteiro. Eles ganhavam R$ 80 por mês. Com o time do Maranhão não tivemos a oportunidade de conversar sobre isso, mas sei que eles ficaram três dias dentro de um ônibus para chegar até São Paulo, algo comum com equipes do Norte ou Nordeste que tentam jogar a principal competição de base do Brasil. As federações ajudam pouco ou nada.

Em 2015, mais de 82% dos jogadores de futebol recebiam menos de R$ 1 mil por mês, segundo a CBF.Eu poderia escrever um livro sobre todas as histórias que eu ouvi ou testemunhei no verdadeiro mundo do futebol. Isto que eu descrevi é a situação atual da imensa maioria dos atletas no Brasil. Mesmo entre os profissionais: em 2015, mais de 82% dos jogadores de futebol recebiam um salário inferior a R$ 1 mil, de acordo com a Confederação Brasileira de Futebol. E deve ter muita história pior, que eu nem sei ou nem imagino. Cada dia é uma surpresa: quando você acha que já viu de tudo, você acaba tomando banho de mangueira na frente do vestiário, porque os chuveiros estão todos estragados. No clube onde isso aconteceu, a água que tomávamos vinha em um cooler – na verdade, era uma mistura de água com grama, com bolhas de óleo por cima. Um amigo meu até brincava “rapaz, a piscina lá de casa é mais limpa que essa água”. Nós que vivemos do futebol não temos ideia do que pode acontecer. Sempre tem algo novo, mas nós não nos damos conta, porque estamos sempre focados no nosso sonho, que é o que nos motiva perante a inúmeras dificuldades e humilhações.

Ramiro jogando pela seleção gaúcha durante a Copa de Seleções Estaduais Sub-20, em 2017.

Foto: arquivo pessoal/Ramiro Simon

Acho que é por isso que o futebol continua. Porque no fundo, no meio de tudo isso, nós temos fé de que um dia sairemos dessa situação, de que um dia vamos alcançar este lugar privilegiado, que poucos conquistam, e que todo mundo assiste na televisão. Por mais impossível que pareça, e que a realidade do mundo grite na nossa cara que não dá, que é um em um milhão que chega lá.

Ainda assim, continuamos. A gente carrega a alma daquela criança sonhadora. Ela ainda sonha dentro de nós, esperando o dia em que nos tornaremos jogadores de futebol. Agora, aos 21, sigo correndo atrás desse objetivo. Sou volante e estou em teste para jogar em um time da primeira divisão do Canadá.

E é por essa persistência que a ganância de quem organiza o futebol passa despercebida. Às vezes até percebemos, mas não tem o que fazer, né? Vamos arriscar nosso sonho reclamando que gostaríamos de um salário digno? Ou de uma alimentação melhor? Ou de uma cama melhor? Ou um ventilador? É assim e deu. Se você incomodar muito, é mandado embora, e eles acham outro por aí. O que mais tem é garoto querendo o nosso lugar. Para a maioria dos que financiam o futebol no país, esses princípios básicos são “desperdício de dinheiro”, porque não dão retorno a curto prazo. Ninguém entrou nessa para perder, não é? E quem paga a conta somos nós. No pior cenário, pagamos com a vida. Foi o que aconteceu com os garotos do Flamengo.

Este é o mundo do futebol: milhares de sonhos no meio de falsidade, ganância, corrupção e egoísmo. E tudo isso longe da família, longe de casa, desde bem cedo. Abrimos mão de tudo pelo nosso objetivo.

Muitos falam que jogador de futebol só fala em Deus. Não é para menos: só Ele é capaz de nos manter firmes diante disso tudo. No papel, as chances são mínimas.

The post ‘Se você incomodar muito, está na rua. O que mais tem é garoto que sonha em viver do futebol.’ appeared first on The Intercept.

In a stinging rebuke to the Trump administration’s cozy relationship with Saudi Arabia, the House of Representatives passed a resolution directing the administration to remove U.S. forces from supporting the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen.

The measure, which passed by a vote of 248-177, is one of the first major pieces of legislation approved by the Democratic House. It is a significant achievement for the progressive wing of the party, whose members have long argued in favor of cutting off military support for Saudi Arabia.

The resolution, which invokes the 1973 War Powers Act, directs President Donald Trump to remove U.S. forces from “hostilities” in the Saudi-led intervention against an Iranian-backed rebel group in Yemen. In both the Trump and Obama administrations, the U.S. has provided weapons, targeting intelligence, and mid-air refueling support for the Saudi-led coalition.

A Republican-sponsored amendment, passed Wednesday, weakened the resolution slightly by allowing continued intelligence sharing with the coalition. The amendment, which passed by a vote of 252-177, allows the U.S. to continue sharing intelligence with foreign powers “if the President determines such sharing is appropriate.”

Under House and Senate rules, the resolution enjoys “privileged” status, meaning that it can bypass a committee vote. The Republican-held Senate passed a similar resolution in December by a vote of 56-41, but with a new Congress, the Senate will have to pass it again to send it to Trump’s desk. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., has promised to bring it up for another vote.

Rep. Ro Khanna, a California Democrat who sponsored the resolution, told The Intercept that the vote was a “historic” assertion of Congress checking war powers.

“This has never happened before — since 1973. It’s Congress reasserting our role in matters of war and peace,” Khanna said. “It’s a major signal to the Saudis to end the war.”

When the House first considered the measure in 2017, it was championed by progressives like Khanna but opposed by Democratic leadership. When supporters reintroduced the measure in September, it had the backing of a number of top Democrats, including Democratic Whip Steny Hoyer, D-Md. The explosion of anger surrounding the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in October drew members from both sides of the aisle, many of whom saw it as a way to hold Saudi leadership accountable.

Humanitarian groups have held the Saudi-led coalition partially responsible for creating the worst humanitarian crisis in the world. Since the war broke out in 2015, coalition warplanes have bombed food sources, water infrastructure, and medical facilities, all while delaying or restricting the flow of food into the country.

On Wednesday, however, debate largely centered on whether it was appropriate for Congress to use the War Powers resolution to check the president’s power.

“The Congress has lost its grip on foreign policy, in my opinion, by giving too much deference to the executive branch,” Elliot Engel, D-N.Y., the chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said Wednesday on the House floor. “Our job is to keep that branch in check, not to shrug our shoulders when they tell us to mind our own business.”

Republicans opposing the bill argued that it would embolden Iran and expressed concern that it could open the door to Congress scrutinizing other U.S. military alliances.

“This overreach has dangerous implications far beyond Saudi Arabia,” said Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas, the top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee. “This approach will now allow any single member to use this privilege mechanism to second-guess U.S. security cooperation relationships with more than 100 countries throughout the world.”

Some progressive advocates welcomed that idea. “It’s no coincidence that progressives, both inside and outside Congress and across the country, drove the House of Representatives to invoke [the War Powers Resolution],” said Kate Kizer, policy director for the progressive group Win Without War. “This historic vote is just the opening salvo of building power behind progressive foreign policy.”

At the last minute, Republicans also managed to add language condemning anti-Semitism, an apparent shot at Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., for a Sunday tweet about the Israel lobby that critics said invoked anti-Semitic tropes.

The post House of Representatives Orders Donald Trump to Stop Backing Saudi-led War in Yemen, Paving the Way for Decisive Senate Vote appeared first on The Intercept.

Immigrant rights groups are reacting angrily to the border deal to keep the government open, which President Donald Trump has said that he will sign into law, averting a shutdown. The bill, which has not yet officially been drafted, gives Trump more than $1 billion in funding for new barriers on the southern border, and funds a potential increase in immigrant detention capacity.

The barriers that the bill would fund are a rhetorical downgrade from Trump’s signature policy of erecting a border wall, which House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., has repeatedly rejected to fund. Funding for immigration detention, which has soared under the Trump administration, was a key issue in talks over keeping the government open. Democrats had pushed for cuts to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s detention budget, but ceded that demand in the interest of moving negotiations forward. The bill would fund the government through September 30.

The central problem with the deal, leaders of the immigrant rights community say, is that Democrats, from a position of strength given their control of the House of Representatives, merely entrenched Trump’s immigration policy. The deal, they say, puts a bipartisan stamp of approval on the dark chapter of American history that Trump’s policies have brought upon us.

Ana María Archila, co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy, said that Democrats appeared to be negotiating as if the November elections hadn’t happened. Trump made the midterms a referendum on his border wall, driving 24/7 news coverage of a migrant caravan walking through Central America. He declared the caravan a national crisis and sent the military to the border.

Voters responded by giving Democrats the biggest midterm win since Watergate.

“Schumer needs to understand that his mandate is different. He’s negotiating as if the elections didn’t matter,” said Archila, referring to Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. “I think that the deal essentially accepts Trump’s paradigm that there is a security crisis at the border that needs more investment and enforcement. It displays a level of a lack of moral grounding in some ways. The country now knows what enforcement looks like. It’s ugly. It’s children in cages. It’s families that’ll never see each other again. That’s what this funding will do.”

Javier Valdes, co-executive director of Make the Road NY, an immigration group, said that if the details of the deal match the reporting, he would urge Congress to reject it. His biggest objection is that it expands immigration enforcement, he said. “There’s been a national conversation about the role of ICE and detention, and folks expected we’d see something that actually decreased the level of detention and came with actual oversight. It’s not just about the wall. It’s the other enforcement mechanisms and the impact they’re having on our communities on a day-to-day basis.”

Republican leaders Sen. Mitch McConnell and Rep. Kevin McCarthy are pushing the deal, but it is not entirely clear how the rest of the GOP caucus, many of whom wanted to see a wall built, will vote on the funding bill. In some ways, opposition from immigration groups and progressives could make the deal more likely to pass, as the outrage convinces Republicans that the deal Trump got does indeed expand his deportation regime.

There are, on average, about 50,000 people in immigration detention on any given day, even though a 2018 spending deal provided funding for 40,520 beds. Democrats had fought to shrink or limit the number of beds available to immigration authorities, in an effort to slow the expansion of the administration’s deportation infrastructure. But the party withdrew that demand under pressure from Republicans, and the new bill allows for the further increase of detention capacity from the current level.

Silky Shah, executive director of Detention Watch Network, lambasted the deal for “making major concessions on detention.”

“The funding bill was a chance to put a check on the detention system, which is a key driver of mass deportations.”“ICE’s budget has skyrocketed and despite this, they keep getting bailed out for overspending. Some action needs to be taken and reducing funding is a start,” Shah said. “The administration is quietly expanding detention all over the country in behind-the-scenes deals with local counties and private contractors, and the funding bill was a chance to put a check on the detention system, which is a key driver of mass deportations.”

Democrats were hamstrung in negotiations by their own previously enthusiastic support for deportations and border enforcement. Before Trump made the issue partisan by demanding a wall during his presidential campaign, both parties eagerly spent billions to militarize the southern border.

“For decades, both parties have built up the deportation [machine] without question, and this deal represents the ‘enforcement-only’ status quo that Washington has been stuck in for too long,” said Greisa Martinez Rosas, deputy executive director of United We Dream and a recipient of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. On Wednesday, activists from United We Dream, which advocates for immigrants who arrived in the United States as children, occupied a portion of the Cannon House Office Building.

“This was an old-fashioned shakedown — Trump threatened to shut down the government again unless Congress gave him and his deportation force more cash to execute their racist vision of mass deportation, and while Democrats gave him the money, immigrant families will pay the price,” Rosas said.

One senior Democratic aide, who was close to the negotiations but not authorized to speak publicly, said that the alternative to the deal that was struck was a continuing resolution, a temporary funding measure that would keep the system running as is. That meant that either way, there would be a further expansion of beds. “That’s the best argument,” he said.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., a co-chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said on Wednesday that she’s still trying to get all the details of the deal, but is strongly leaning toward voting no because of “the lack of accountability around the detention system” and the increased number of detention beds.

She said she would like a guarantee from the Trump administration that the Department of Homeland Security will use its funds as appropriated by Congress, instead of moving money around to fund the wall, as Trump has threatened. “Without that accountability, it becomes very difficult to approve that,” Jayapal said.

Rep. Adriano Espaillat, D-N.Y., said he’s “leaning as a strong no” on the deal. “I think for far too many times, Dreamers and immigration reform in general get pushed to the back,” Espaillat told The Intercept. “And we won’t have comprehensive immigration reform on a nice sunny day or on a spring morning. We will have it in the middle of a crisis that will yield a give and take, that will force people to reach a consensus, and I think we missed another opportunity.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., also told The Intercept she will “probably be voting no.”

The post Immigrant Rights Groups Trash Border Deal: “Immigrant Families Will Pay the Price” appeared first on The Intercept.

Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York City who now serves as President Donald Trump’s personal lawyer, called for the overthrow of Iran’s government on Wednesday during a rally in Poland staged by a cult-like group of Iranian exiles who pay him to represent them.

Speaking outside the Warsaw venue for an international conference on the Middle East attended by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Giuliani said that his message for the 65 governments discussing ways to confront Iran was simple. “The theocratic dictatorship in Tehran,” Giuliani said, “must end and end quickly.”

Former NY Mayor @RudyGiuliani in Warsaw:

In order to have peace & security in the Mid-East there has to be a major change in the theocratic dictatorship in #Iran. It must end & end quickly in order to have stability#FreeIranWithMaryamRajavi#PolandSummit#IStandWithMaryamRajavi pic.twitter.com/aKafMjxq4k

— NCRI-FAC (@iran_policy) February 13, 2019

Giuliani went on to suggest that peace in the region would only come when Iran was ruled instead by his clients, the National Council of Resistance of Iran, an exile group of former terrorists also known as the Mojahedin-e Khalq, or People’s Mujahedin. The group’s leader, Maryam Rajavi, already refers to herself as “President-elect.”

.@RudyGiuliani: We have seen regime change work & fail. In #Iran's case we don’t have to worry. There is a viable alternative. Maryam Rajavi's 10-point plan stands for a #FreeIran w/ a democratically-elected Gov instead of a tyrant/monarch.#FreeIranWithMaryamRajavi #WarsawSummit pic.twitter.com/EFJHIw2WUV

— NCRI-FAC (@iran_policy) February 13, 2019

Off-stage, the U.S. president’s lawyer admitted that he was paid by the exile group, but stressed to reporters that he was in Warsaw on behalf of the MEK in his personal capacity and would not be attending the diplomatic conference organized by the State Department.

Even before the conference began, the Israeli prime minister appeared to shrug off efforts by the State Department and the Polish government to portray the gathering as broadly focused on Middle East peace, describing it as primarily a meeting of Iran’s enemies.

In video posted on the prime minister’s official Twitter feed, Netanyahu characterized a meeting with Oman’s foreign minister as “excellent,” and one focused on “additional steps we can take together with the countries of the region in order to advance common interests.”

According to the English translation of Netanyahu’s remarks in Hebrew prepared by his office, the prime minister then added: “What is important about this meeting — and it is not in secret because there are many of those — is that this is an open meeting with representatives of leading Arab countries that are sitting down together with Israel in order to advance the common interest of war with Iran.”

A screenshot from video posted on the official Twitter feed of Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

Netanyahu’s use of the word “war” seemed to throw Israel’s diplomatic corps into chaos. Within minutes, as journalists speculated that the prime minister’s office might have mistranslated his comment, Netanyahu’s spokesperson to the Arab media, Ofir Gendelman, wrote that the Israeli leader had described his nation’s common interest with Arab nations as “combatting Iran,” not “war with Iran.”

The subtitled video produced by the prime minister’s office was then deleted from his Twitter feed and replaced with the text of Gendelman’s alternative translation.

As my colleague Talya Cooper explains, however, Netanyahu did in fact use the Hebrew word for “war” in the video, which has not yet been deleted from his Hebrew-language YouTube channel. In a separate video, posted by Netanyahu’s office on Facebook earlier in the day, the prime minister had used the Hebrew word for “combat.”

Aron Heller, an Associated Press correspondent based in Jerusalem, also filmed the remarks and reported that although Netanyahu had mentioned “war,” his office said later that he was referring to “combatting Iran.”

Did @netanyahu really say “war” with Iran? I was there and the word was ”milchama” = war. pic.twitter.com/ZzhrDs2lWA

— Aron Heller (@aronhellerap) February 13, 2019

Iran’s foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, seized on the Israeli leader’s apparent Freudian slip as evidence that Netanyahu’s true aim of provoking a war with Iran was now out in the open.

We've always known Netanyahu's illusions. Now, the world – and those attending #WarsawCircus – know, too pic.twitter.com/0TSDzIak9e

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) February 13, 2019

Zarif also suggested that the Trump administration and the exiles of the MEK might have been behind a suicide bombing on a bus in southeastern Iran on Wednesday, which killed 41 members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.

“Is it no coincidence that Iran is hit by terror on the very day that #WarsawCircus begins?” Zarif tweeted. “Especially when cohorts of same terrorists cheer it from Warsaw streets & support it with twitter bots? US seems to always make the same wrong choices, but expect different results.”

The foreign minister was clearly referring to the MEK, which spent three decades trying to achieve regime change in Iran through violence, including terrorist attacks. The well-funded exile group was also suspected of being behind social media trickery discovered by the BBC, which reported that Twitter bots had been deployed “to artificially create a trend which hints at popular support for the summit and — by extension — widespread resentment towards the Iranian establishment.”

The Iranian exiles have been caught in the past paying nonsupporters to fill out its crowds at rallies, a tactic reportedly used at the event in Warsaw on Wednesday, according to journalists on the ground.

The MEK is having a rally in Warsaw where as usual about a third of the crowd is random non-Iranians who've been bussed in from Slovakia and can't read the signs they're holding pic.twitter.com/NnJyqMxnEY

— Gregg Carlstrom (@glcarlstrom) February 13, 2019

Spoke to journalist in #WarsawSummit. He had attended the MEK terrorist org's rally. Many of the "demonstartors" were Slovak high school kids who couldnt really provide an answer as to why they were there.

Just as the MEK buys bots on Twitter, they do so in real life as well…

— Trita Parsi (@tparsi) February 13, 2019

Members of the MEK helped foment the 1979 Iranian revolution, in part by killing American civilians working in Tehran, but the group then lost a struggle for power to the Islamists. With its leadership forced to flee Iran in 1981, the MEK’s members set up a government-in-exile in France and established a military base in Iraq, where they were given arms and training by Saddam Hussein as part of a strategy to destabilize the government in Tehran that he was at war with.

In recent years, as The Intercept has reported, the MEK has poured millions of dollars into reinventing itself as a moderate political group ready to take power in Iran if Western-backed regime change ever takes place. To that end, it lobbied successfully to be removed from the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations in 2012. The Iranian exiles achieved this over the apparent opposition of then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, in part by paying a long list of former U.S. officials from both parties hefty speaking fees of between $10,000 to $50,000 for hymns of praise.

Despite the claims of paid spokespeople like Giuliani and John Bolton — who predicted regime change would come at a lavish MEK rally in Paris just months before being named Trump’s national security adviser — the MEK appears to be as unprepared to take power in Iran as Ahmad Chalabi’s exiled Iraqi National Congress was after the American invasion of Iraq.

#JohnBolton 8 months ago among MEK supporters tells them they will overthrow #Iran’s regime and celebrate in #Tehran with Bolton himself present, “before 2019” pic.twitter.com/H7oaaU3faU

— Bahman Kalbasi (@BahmanKalbasi) March 22, 2018

Ariane Tabatabai, a Georgetown University scholar, has argued that the “cult-like dissident group” — whose married members were reportedly forced to divorce and take a vow of lifelong celibacy — “has no viable chance of seizing power in Iran.”

If the current government is not Iranians’ first choice for a government, the MEK is not even their last — and for good reason. The MEK supported Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq War. The people’s discontent with the Iranian government at that time did not translate into their supporting an external enemy that was firing Scuds into Tehran, using chemical weapons and killing hundreds of thousands of Iranians, including many civilians. Today, the MEK is viewed negatively by most Iranians, who would prefer to maintain the status quo than rush to the arms of what they consider a corrupt, criminal cult.

Despite such doubts, spending lavishly on paid endorsements has earned the MEK a bipartisan roster of Washington politicians willing to sign up as supporters. At a gala in 2016, Bolton was joined in singing the group’s praises by another former U.N. ambassador, Bill Richardson; a former attorney general, Michael Mukasey; the former State Department spokesperson P.J. Crowley; the former Homeland Security adviser Frances Townsend; the former Rep. Patrick Kennedy, D-R.I.; and the former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean. That Paris gala was hosted by Linda Chavez, a former Reagan administration official, and headlined by Newt Gingrich, the former speaker who was under consideration to be Trump’s running mate at the time.

Fears about Bolton’s apparently open desire to start a war with Iran have been exacerbated by his boosting of the MEK and his steadfast denial of the catastrophe unleashed by the invasion of Iraq that he worked for as a member of the Bush administration. Last year, when Fox News host Tucker Carlson pointed out that Bolton had called for regime change in Iraq, Libya, Iran, and Syria, and the first of those had been “a disaster,” Bolton disagreed.

“I think the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, that military action, was a resounding success,” Bolton insisted to Carlson. The chaos that followed in Iraq, he said, was caused by a poorly executed occupation that ended too soon. On the bright side, Bolton said, the mistakes the U.S. made in Iraq offered “lessons about what to do after a regime is overthrown” in the future.

Earlier this week, Sen. Chris Murphy pointed out, Bolton appeared to be laying the groundwork for war in a belligerent video message from the White House to mark the 40th anniversary of the Iranian revolution.

Here Bolton says Iran is seeking nuclear weapons. This simply isn’t true. The intelligence says the opposite and he knows it. He is laying the groundwork for war and we all must be vigilant. https://t.co/1zHR5vaEGn

— Chris Murphy (@ChrisMurphyCT) February 12, 2019

The post As Rudy Giuliani Calls for Regime Change in Iran, Benjamin Netanyahu Raises the Specter of “War” appeared first on The Intercept.

A former Goldman Sachs lobbyist who now works as the top lawyer for Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., declined to name 19 of his 20 former clients in his financial disclosure last year.

Mark Patterson, who also served as former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s chief of staff during the Obama administration, joined Schumer’s office last year. He had been a co-chair of the Perkins Coie law firm’s public and strategic affairs practice since 2014.

An archived version of Perkins Coie’s website says that Patterson provided “policy analysis and strategic counsel to clients such as major corporations, financial institutions and nonprofit organizations.” He gave few specifics in his 2018 financial disclosure, asserting that he had to withhold the identities of nearly all of his clients based on rules of professional conduct for lawyers.

It’s the same rationale that former Sen. Jon Kyl, R-Ariz., used last month to avoid naming nine of his 36 previous clients, as The Intercept previously reported.

A Schumer spokesperson did not respond to questions.

At Schumer’s office, Patterson is now at the center of a fight over corporate governance. Since President Donald Trump took office, organizations like Demand Progress and the Revolving Door Project have pressured Schumer to use the limited powers at his disposal to encourage stricter oversight by recommending progressive watchdogs to regulatory agency boards. (Schumer, as minority leader, selects appointees for Democratic seats on regulatory bodies, who then need to be formally nominated by the White House).

The effort has produced mixed results: Although Schumer last year proposed nominees that progressives support, the White House didn’t nominate two of them, and Republicans didn’t hold votes on the other two nominees.

A coalition of 20 organizations recently wrote to Schumer demanding that he work to fill Democratic vacancies at the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the Merit Systems Protection Board. The letter faulted Schumer for allowing Trump’s judicial nominees to win confirmation by unanimous consent. Schumer could have used those vacancies as leverage to force votes on his party’s regulatory nominees, the progressives argued.

HuffPost this week called the fight over the regulatory bodies a “moment of truth” for Schumer and Senate Democrats. Jeff Hauser, who leads the Revolving Door Project in Washington, D.C., believes that Patterson deserves some blame for the botched vacancies. After Patterson was hired, Schumer’s office told The Nation that the former Goldman lobbyist — unlike his predecessor — wouldn’t be involved in vetting appointments to federal commissions. That’s a problem, said Hauser.

“I think we should in general try to not hire people for senior jobs where they’re going to be recused from certain matters,” Hauser said. “It would make sense that your chief counsel would be involved in the SEC and FDIC hiring process. It’s something you want your chief counsel to be involved in. If he is complying with his recusal, that might explain the relative indifference, because the senior person on leadership staff who should be raising alarms that these nominations are languishing with Trump is disempowered.”

Hauser said Patterson’s financial disclosure “illustrates a lot of the weakness in our ethics rules, because there is insufficient skepticism about self-reported matters.”

“We only have his word that those 19 clients required that level of confidentiality,” Hauser said. “If he’s hiding his clients, it’s hard to even know what we don’t want him involved in, by definition, because he’s preventing us the ability to know what is a conflict of interest.”

This story is a collaboration between The Intercept and MapLight, a nonpartisan research organization that tracks money’s influence on politics.

The post Goldman Lobbyist Turned Schumer General Counsel Is Hiding Most Former Clients’ Names appeared first on The Intercept.

American descendants of slaves identifying themselves with the hashtag #ADOS have been openly critical of 2020 presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Cory Booker over the past weeks.

Some prominent black political commentators are now speculating that these critics are Russian bots.

Angela Rye, a CNN political commentator and board member of the Congressional Black Caucus PAC, has said she believes that some ADOS arguments are not organic, but were “paid for by Russia.” She added that she’s “not saying everyone who uses the hashtag is a Russian bot,” but she does believe “it originated from Russian bots.” Rye went on to argue that the same is true of critiques relating to “some of the stuff around the crime bill” circa 2016 — presumably referring to critics of Hillary Clinton who questioned her support of the bill now widely understood to have caused overwhelming harm to black Americans.

We stand with #ados #notabot #tonetalks #angelaproject pic.twitter.com/9t1ty9cVeW

— Amos Jones (@amosnjones) February 5, 2019

On a segment of Joy Reid’s MSNBC show titled “how to spot a bot,” Shireen Mitchell, founder of Stop Online Violence Against Women, argued that the ADOS hashtag is a way to identify foreign influence. “A lot of the ones that are pretending to be black people, black women in particular, who are focusing on black identity, have these sort of aspects in the ways that they’re talking about language,” she said. She went on to say that bots are posing as black Americans using “the vernacular or the language of someone that believes they are a part of our community” to claim authority to represent black Americans.

“This has become a challenge particularly for the Democratic candidates because obviously, in 2016, all this activity was directed to help Donald Trump, or to hurt Hillary Clinton, to do both,” Reid said. “So I’m wondering if this time the party is going to be a bit more prepared. Reid appeared to co-sign Mitchell’s claim, saying, “I did see a huge uptick of bot activity when Kamala Harris announced,” focusing on critics who argue that Harris “is not really black.”

For years, identifying as a black American “descendant” of slaves or ADOS has been a way for black Americans to advocate for the specific needs and interests of those brought to the United States via the transatlantic slave trade hundreds of years ago, as distinct from the interests of more recent African and Caribbean immigrants.

Some critics using the ADOS hashtag have focused on Harris’s race, pointing to Kamala’s Indian and Jamaican heritage as a possible explanation for why, as a prosecutor, she supported policies that disproportionately harmed black Americans. The ADOS movement does have some nativist elements. But it is also true that much of the commentary surrounding Harris appears to relate less to her racial background than her public record. Booker, also a target of ADOS criticism, is an American descendant of slavery himself.

As Attorney General Kamala opposed legislation requiring her office investigate police shootings. When CA was ordered to reduce prison overcrowding she argued against it. The question is basic: Would you elect @SheriffClarke? What's the hell is the difference? #ADOS #kamalaharris pic.twitter.com/LQwdy57UQr

— Tim Black ™ (@RealTimBlack) February 11, 2019

The creators of the hashtag — Antonio Moore, an attorney in California, and Yvette Carnell, a political commentator — are neither Russian nor bots and are demanding an apology.

Carnell told The Intercept that she thinks calling out ADOS is an effort to delegitimize the grassroots movement they’ve worked to cultivate and to “undermine a real debate that we have about Kamala Harris within the black community.” For years, Moore and Carnell have been doing regular YouTube and radio shows together where they discuss issues like reparations and the racial wealth divide under the lens of “native descendants of American slaves.”

Moore said that accusations like Reid’s are a McCarthyite tactic in the same vein as the attempts to publicly discredit Martin Luther King Jr. “It’s troubling, the lengths that these people will go to undermine authentic Black advocacy in order to prop up the Democratic establishment,” he said in an email. An MSNBC spokesperson declined to comment.

Indeed, people of color who challenge the Democratic Party from the left are often erased or dismissed as somehow not being real. During the 2016 Democratic primary, the hashtag #BernieMadeMeWhite spread as a response to the “Bernie Bro” stereotype, which wrongly claimed that nearly all Bernie Sanders supporters were young white men.

Carnell and Moore cited a truancy program Harris created as San Francisco’s district attorney that threatened parents with prosecution if their children missed school — a policy that progressives argue disproportionately hurts minority and low-income communities — as one of their main criticisms of her. As for Booker, they said they have a problem with his corporate alliances, specifically his ties to the pharmaceutical industry and widely criticized vote against allowing drug reimportation to the United States.

So….

Reparations for #ADOS

Debilitating effects of the Crime Bill

Questionable acts of Kamala Harris’ AG tenure

Dems lack of specific policies that roll back effects of injustice

are ‘divisive’ issues put out by Russian bots and not legitimate concerns of Black people?

— Bishop Talbert Swan (@TalbertSwan) February 4, 2019

Moore said they will be holding their first American DOS conference in Louisville, Kentucky, on October 4-5, and intend to ask Booker and Harris to attend to “talk to black Americans about what their black agenda is.”

This is not the first time Reid has dabbled in conspiracy theories. Last year, Reid found herself in hot water when decade-old homophobic blog posts resurfaced. Instead of immediately apologizing, Reid told Mediaite — without offering any evidence — that hackers planted the offensive blog posts as “part of an effort to taint my character with false information by distorting a blog that ended a decade ago.”

Correction: February 13, 2019, 11:52 a.m.

Due to editing errors, a previous version of this article stated that Cory Booker is a “defendant” of slavery, rather than a “descendant.” The article also misgendered Yvette Carnell, who uses “she” pronouns.

The post Black Critics of Kamala Harris and Cory Booker Push Back Against Claims That They’re Russian “Bots” appeared first on The Intercept.

“I really don’t like their policies of taking away your car, taking away your airplane flights, of ‘let’s hop a train to California,’ or ‘you’re not allowed to own cows anymore!'”

So bellowed President Donald Trump in El Paso, Texas, his first campaign-style salvo against Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ed Markey’s Green New Deal resolution. There will surely be many more.

It’s worth marking the moment. Because those could be the famous last words of a one-term president, having wildly underestimated the public appetite for transformative action on the triple crises of our time: imminent ecological unraveling, gaping economic inequality (including the racial and gender wealth divide), and surging white supremacy.

Or they could be the epitaph for a habitable climate, with Trump’s lies and scare tactics succeeding in trampling this desperately needed framework. That could either help win him re-election, or land us with a timid Democrat in the White House with neither the courage nor the democratic mandate for this kind of deep change. Either scenario means blowing the handful of years left to roll out the transformations required to keep temperatures below catastrophic levels.

Back in October, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a landmark report informing us that global emissions need to be slashed in half in less than 12 years, a target that simply cannot be met without the world’s largest economy playing a game-changing leadership role. If there is a new administration ready to leap into that role in January 2021, meeting those targets would still be extraordinarily difficult, but it would be technically possible — especially if large cities and states like California and New York escalate their ambitions right now. Losing another four years to a Republican or a corporate Democrat, and starting in 2026 is, quite simply, a joke.

So either Trump is right and the Green New Deal is a losing political issue, one he can smear out of existence. Or he is wrong and a candidate who makes the Green New Deal the centerpiece of their platform will take the Democratic primary and then kick Trump’s ass in the general, with a clear democratic mandate to introduce wartime-levels of investment to battle our triple crises from day one. That would very likely inspire the rest of the world to finally follow suit on bold climate policy, giving us all a fighting chance.

Those are the stark options before us. And which outcome we end up with depends on the actions taken by social movements in the next two years. Because these are not questions that will be settled through elections alone. At their core, they are about building political power — enough to change the calculus of what is possible.

That was the lesson of the original New Deal, one we would be wise to remember right now.

The New Deal was a process as much as a project, one that was constantly changing and expanding in response to social pressure from both the right and the left.Ocasio-Cortez chose to model the Green New Deal after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s historic raft of programs understanding full well that a central task is to make sure that this mobilization does not repeat the ways in which its namesake excluded and further marginalized many vulnerable groups. For instance, New Deal-era programs and protections left out agricultural and domestic workers (many of them black), Mexican immigrants (some 1 million of whom faced deportation in the 1930s), and Indigenous people (who won some gains but whose land rights were also violated by both massive infrastructure projects and some conservation efforts).

Indeed, the resolution calls for these and other violations to be actively redressed, listing as one of its core goals “stopping current, preventing future, and repairing historic oppression of indigenous peoples, communities of color, migrant communities, deindustrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth.”

I have written before about why the old New Deal, despite its failings, remains a useful touchstone for the kind of sweeping climate mobilization that is our only hope of lowering emissions in time. In large part, this is because there are so few historical precedents we can look to (other than top-down military mobilizations) that show how every sector of life, from forestry to education to the arts to housing to electrification, can be transformed under the umbrella of a single, society-wide mission.

Which is why it is so critical to remember that none of it would have happened without massive pressure from social movements. FDR rolled out the New Deal in the midst of a historic wave of labor unrest: There was the Teamsters’ rebellion and Minneapolis general strike in 1934, the 83-day shutdown of the West Coast by longshore workers that same year, and the Flint sit-down autoworkers strikes in 1936 and 1937. During this same period, mass movements, responding to the suffering of the Great Depression, demanded sweeping social programs, such as Social Security and unemployment insurance, while socialists argued that abandoned factories should be handed over to their workers and turned into cooperatives. Upton Sinclair, the muckraking author of “The Jungle,” ran for governor of California in 1934 on a platform arguing that the key to ending poverty was full state funding of workers’ cooperatives. He received nearly 900,000 votes, but having been viciously attacked by the right and undercut by the Democratic establishment, he fell just short of winning the governor’s office.

All of this is a reminder that the New Deal was adopted by Roosevelt at a time of such progressive and left militancy that its programs — which seem radical by today’s standards — appeared at the time to be the only way to hold back a full-scale revolution.

It’s also a reminder that the New Deal was a process as much as a project, one that was constantly changing and expanding in response to social pressure from both the right and the left. For example, a program like the Civilian Conservation Corps started with 200,000 workers, but when it proved popular eventually expanded to 2 million. That’s why the fact that there are weaknesses in Ocasio-Cortez and Markey’s resolution — and there are a few — is far less compelling than the fact that it gets so much exactly right. There is plenty of time to improve and correct a Green New Deal once it starts rolling out (it needs to be more explicit about keeping carbon in the ground, for instance, and about nuclear and coal never being “clean”). But we have only one chance to get this thing charged up and moving forward.

The more sobering lesson is that the kind of mass power that delivered the victories of the New Deal era is far beyond anything possessed by current progressive movements, even if they all combined efforts. That’s why it is so urgent to use the Green New Deal framework as a potent tool to build that power — a vision to both unite movements and dramatically expand them.

Part of that involves turning what is being derided as a left-wing “laundry list” or “wish list” into an irresistible story of the future, connecting the dots between the many parts of daily life that stand to be transformed — from health care to employment, day care to jail cell, clean air to leisure time.

Right now, the Green New Deal reads like a list because House resolutions have to be formatted as lists — lettered and numbered sequences of “whereases” and “resolveds.” It’s also being characterized as an unrelated grab bag because most of us have been trained to avoid a systemic and historical analysis of capitalism and to divide pretty much every crisis our system produces — from economic inequality to violence against women to white supremacy to unending wars to ecological unraveling — in walled-off silos. From within that rigid mindset, it’s easy to dismiss a sweeping and intersectional vision like the Green New Deal as a green-tinted “laundry list” of everything the left has ever wanted.

Now that the resolution is out there, however, the onus is on all of us who support it to help make the case for how our overlapping crises are indeed inextricably linked — and can only be overcome with a holistic vision for social and economic transformation. This is already beginning to happen. For example, Rhiana Gunn-Wright, who is heading up policy for a new think tank largely focused on the Green New Deal, recently pointed out that just as thousands of people moved for jobs during the World War II-era economic mobilization, we should expect a great many to move again to be part of a renewables revolution. And when they do, “unlinking employment from health care means people can move for better jobs, to escape the worst effects of climate, AND re-enter the labor mkt without losing” (her whole Twitter thread is worth reading).

Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images

Investing big in public health care is also critical in light of the fact that no matter how fast we move to lower emissions, it is going to get hotter and storms are going to get fiercer. When those storms bash up against health care systems and electricity grids that have been starved by decades of austerity, thousands pay the price with their lives, as they so tragically did in post-Maria Puerto Rico.

And there are many more connections to be drawn. Those complaining about climate policy being weighed down by supposedly unrelated demands for access to health care and education would do well to remember that the caring professions — most of them dominated by women — are relatively low carbon and can be made even more so. In other words, they deserve to be seen as “green jobs,” with the same protections, the same investments, and the same living wages as male-dominated workforces in the renewables, efficiency, and public-transit sectors. Meanwhile, as Gunn-Wright points out, to make those sectors less male-dominated, family leave and pay equity are a must, which is part of the reason both are included in the resolution.

Drawing out these connections in ways that capture the public imagination will take a massive exercise in participatory democracy. A first step is for every sector touched by the Green New Deal — hospitals, schools, universities, and more — to make their own plans for how to rapidly decarbonize while furthering the Green New Deal’s mission to eliminate poverty, create good jobs, and close the racial and gender wealth divides.

My favorite example of what this could look like comes from the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, which has developed a bold plan to turn every post office in Canada into a hub for a just green transition. Think solar panels on the roof, charging stations out front, a fleet of domestically manufactured electric vehicles from which union members don’t just deliver mail, but also local produce and medicine, and check in on seniors — all supported by the proceeds of postal banking.

To make the case for a Green New Deal — which explicitly calls for this kind of democratic, decentralized leadership — every sector in the United States should be developing similar visionary plans for their workplaces right now. And if that doesn’t motivate their members to rush the polls come 2020, I don’t know what will.

We have been trained to see our issues in silos; they never belonged there. In fact, the impact of climate change on every part of our lives is far too expansive and extensive to begin to cover here. But I do need to mention a few more glaring links that many are missing.

A job guarantee, far from an opportunistic socialist addendum, is a critical part of achieving a rapid and just transition. It would immediately lower the intense pressure on workers to take the kinds of jobs that destabilize our planet because all would be free to take the time needed to retrain and find work in one of the many sectors that will be dramatically expanding.

This in turn will reduce the power of bad actors like the Laborers’ International Union of North America who are determined to split the labor movement and sabotage the prospects for this historic effort. Right out of the gate, LIUNA came out swinging against the Green New Deal. Never mind that it contains stronger protections for trade unions and the right to organize than anything we have seen out of Washington in three decades, including the right of workers in high-carbon sectors to democratically participate in their transition and to have jobs in clean sectors at the same salary and benefits levels as before.

A job guarantee, far from an opportunistic socialist addendum, is a critical part of achieving a rapid and just transition.There is absolutely no rational reason for a union representing construction workers to oppose what would be the biggest infrastructure project in a century, unless LIUNA actually is what it appears to be: a fossil fuel astroturf group disguised as a trade union, or at best a company union. These are the same labor leaders, let us recall, who sided with the tanks and attack dogs at Standing Rock; who fought relentlessly for the construction of the planet-destabilizing Keystone XL pipeline; and who (along with several other building trade union heads) aligned themselves with Trump on his first day in office, smiling for a White House photo op and declaring his inauguration “a great moment for working men and women.”

LIUNA’s leaders have loudly demanded unquestioning “solidarity” from the rest of the trade union movement. But again and again, they have offered nothing but the narrowest self-interest in return, indifferent to the suffering of immigrant workers whose lives are being torn apart under Trump and to the Indigenous workers who saw their homeland turned into a war zone. The time has come for the rest of the labor movement to confront and isolate them before they can do more damage. That could take the form of LIUNA members, confident that the Green New Deal will not leave them behind, voting out their pro-boss leaders. Or it could end with LIUNA being tossed out of the AFL-CIO for planetary malpractice.

The more unionized sectors like teaching, nursing, and manufacturing make the Green New Deal their own by showing how it can transform their workplaces for the better, and the more all union leaders embrace the growth in membership they would see under the Green New Deal, the stronger they will be for this unavoidable confrontation.

One last connection I will mention has to do with the concept of “repair.” The resolution calls for creating well-paying jobs “restoring and protecting threatened, endangered, and fragile ecosystems,” as well as “cleaning up existing hazardous waste and abandoned sites, ensuring economic development and sustainability on those sites.”

This is a potential lifeline that we all have a sacred and moral responsibly to reach for.There are many such sites across the United States, entire landscapes that have been left to waste after they were no longer useful to frackers, miners, and drillers. It’s a lot like how this culture treats people. It’s what has been done to so many workers in the neoliberal period, using them up and then abandoning them to addiction and despair. It’s what the entire carceral state is about: locking up huge sectors of the population who are more economically useful as prison laborers and numbers on the spreadsheet of a private prison than they are as free workers. And the old New Deal did it too, by choosing to exclude and discard so many black and brown and women workers.

There is a grand story to be told here about the duty to repair — to repair our relationship with the earth and with one another, to heal the deep wounds dating back to the founding of the country. Because while it is true that climate change is a crisis produced by an excess of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, it is also, in a more profound sense, a crisis produced by an extractive mindset — a way of viewing both the natural world and the majority of its inhabitants as resources to use up and then discard. I call it the “gig and dig” economy and firmly believe that we will not emerge from this crisis without a shift in worldview, a transformation from “gig and dig” to an ethos of care and repair.

If these kinds of deeper connections between fractured people and a fast-warming planet seem far beyond the scope of policymakers, it’s worth thinking back to the absolutely central role of artists during the New Deal era. Playwrights, photographers, muralists, and novelists were all part of a renaissance of both realist and utopian art. Some held up a mirror to the wrenching misery that the New Deal sought to alleviate. Others opened up spaces for Depression-ravaged people to imagine a world beyond that misery. Both helped get the job done in ways that are impossible to quantify.

In a similar vein, there is much to learn from Indigenous-led movements in Bolivia and Ecuador that have placed at the center of their calls for ecological transformation the concept of buen vivir, a focus on the right to a good life as opposed to more and more and more life of endless consumption, an ethos that is so ably embodied by the current resident of the White House.

The Green New Deal will need to be subject to constant vigilance and pressure from experts who understand exactly what it will take to lower our emissions as rapidly as science demands, and from social movements that have decades of experience bearing the brunt of false climate solutions, whether nuclear power, the chimera of carbon capture and storage, or carbon offsets.

But in remaining vigilant, we also have to be careful not to bury the overarching message: that this is a potential lifeline that we all have a sacred and moral responsibly to reach for.

The young organizers in the Sunrise Movement, who have done so much to galvanize the Green New Deal momentum, talk about our collective moment as one filled with both “promise and peril.” That is exactly right. And everything that happens from here on in should hold one in each hand.

The post The Battle Lines Have Been Drawn on the Green New Deal appeared first on The Intercept.

Congress has reportedly reached an agreement to fund the government and avoid another shutdown on Saturday, though with the grumbling in conservative circles about the deal, it’s anyone’s guess whether President Donald Trump will sign it. But even if the government doesn’t shut down again, the rare breakout of competence will have come too late for people like Dorothy Leong of Stratford, Connecticut.

Leong, 83, took out a reverse mortgage on her home in 2004, which gives seniors with equity in their home the opportunity to take money out and defer repayment until they die or resell the property. She used up the line of credit from the reverse mortgage long ago and receives no more money from the deal, but as with all reverse mortgages, she’s still required to cover property taxes and homeowner’s insurance. At the same time, Leong suffers from multiple medical maladies, including a recent heart attack and problems with her legs. With health care bills mounting, and her family’s only means of support being her Social Security check and a meager income from her disabled adult son, Leong eventually fell behind on tax and insurance payments.

Leong’s condition qualifies her for a government program called an “at-risk extension.” The Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, which oversees the reverse-mortgage program, allows homeowners over 80 who have serious medical conditions to avoid foreclosure if they miss housing-related payments. The program seeks to avoid the cruelty of throwing sick elderly people out onto the street.

The at-risk extension, however, must be renewed every year. Leong was approved at the end of 2017 but needed a renewal at the end of last year. “Our experience is, if the doctor says these are the issues, HUD approves it,” said Sarah White, an attorney representing Leong, who sent her request for an extension to HUD on December 10. The government shut down 12 days later, and nobody at HUD ever approved the renewal.

Leong’s at-risk extension lapsed, and she was served with a foreclosure notice in late January on the home she’s lived in since 1962.

The case is one of several scenarios in which lack of staffing during a government shutdown could leave borrowers at risk of preventable, unnecessary foreclosures. HUD and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA, which is also involved with home loans, have provided no data about how many foreclosures were advanced during the shutdown. But with critical bottlenecks inherent in the process, housing advocates warn that the number could be high — and even one preventable foreclosure is a policy tragedy.

A closed meeting room at the Capitol, as bipartisan House and Senate bargainers negotiate to avoid another government shutdown in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 11, 2019.

Photo: Andrew Harnik/AP

If another shutdown hits, the backlog of cases would only increase. “People are losing homes that don’t need to,” said Alys Cohen, staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center’s Washington office.

HUD spokesperson Brian Sullivan said that the agency is finalizing its contingency plan in the event of another government shutdown, including how to address foreclosure timelines. He declined to comment on how HUD was handling leftover cases from the initial shutdown, like Leong’s. USDA did not respond to a request for comment.

Over 9 million borrowers have loans provided or insured by either HUD or USDA. The majority of them are low-income individuals, seniors, or rural residents.

In addition to reverse mortgages, HUD insures loans through the Federal Housing Administration. Meanwhile, the USDA’s Farm Service Agency has two types of loan programs: a loan-guarantee program, which, like the Federal Housing Administration, backs mortgages made with private lenders, and a Direct Farm Ownership Loan program, in which the government issues the mortgages itself.

Direct loans can go toward the down payment or purchase of farms or ranches, expansion or renovation of an existing plot, or to fund capital expenses. They are often heavily subsidized, with monthly payments rising or falling depending on farm income. “I have clients with payments of $120 a month,” said Geoffrey Walsh, a staff attorney with the National Consumer Law Center.

These variable payments mean that farmers must constantly report their income so that the Farm Service Agency can adjust payments or approve an alternative to foreclosure. All FSA direct loans are handled through one centralized servicing center in St. Louis. And when the shutdown happened, that servicing center closed its doors.

“Nobody was answering the phone for 35 days,” said Walsh, describing the chaotic situation during the nation’s largest-ever government shutdown. Not only could alterations to direct-loan payments not be updated, but struggling borrowers at risk of foreclosure could also not be considered for loss mitigation programs to stay current on their loans.

While foreclosures on direct USDA loans are handled by private servicing companies or in some cases the local U.S. Attorney’s office, if there are disagreements over the amount owed or requests for hardship assistance, answers must come through the USDA’s centralized servicing center. Meanwhile, most foreclosures have timelines for borrower action to stop the march toward eviction and sale of the property. “None of those clocks stopped running during the shutdown,” Walsh said.

Eventually, the USDA caught on to the shutdown’s detrimental impact on farmers — yet it seemed unperturbed by the specific harms facing mortgage borrowers. On January 22, the agency reopened Farm Services Agency offices to assist farmers, but explicitly excluded Farm Ownership loans from the list of programs that would be serviced. The USDA told the National Consumer Law Center that it stopped foreclosure sales during the shutdown, but it never clarified how it handled foreclosure timelines.

The National Consumer Law Center asked the USDA for a stay of all foreclosure activity on its loans during the shutdown, but received no response. “There was no written guidance from USDA about what they were doing,” said Steven Sharpe, an attorney with the Legal Aid Society of Southwest Ohio.

In January, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution profiled Willie Donaldson, a homeowner caught up in this situation. After losing his job due to a stroke, Donaldson appealed to the USDA’s rural housing program, which assisted him with his loan to help prevent foreclosure. But nobody answered the phone. His foreclosure hearing was scheduled for February 5.

When the shutdown ended, problems for USDA borrowers were not immediately alleviated. The centralized servicing center needs to work through a tremendous backlog of claims and appeals, with no additional funding support to accelerate the process. “We think it’s still a mess,” said Walsh.

The situation at HUD is similar to the USDA. In addition to reverse mortgage homeowners with at-risk extensions like Leong, newly widowed spouses whose names aren’t on the reverse mortgage need assistance from HUD to keep foreclosure at bay. But HUD officials who typically approve this deferral were furloughed during the shutdown. Borrowers with Federal Housing Administration-insured loans can normally contact HUD personnel for assistance to prevent avoidable foreclosures, like loss mitigation options; this help was also not available during the shutdown since the main point of assistance, the agency’s national servicing center, was almost entirely furloughed.

Advocates asked HUD for a foreclosure moratorium during the shutdown, without a response. “A couple times, we wrote to HUD and someone responded that they would do something on that case,” said Cohen of NCLC. “But it can’t be the case that you have to send an email to Alys Cohen to get your foreclosure stopped.”

White, Leong’s attorney, said her client was served with foreclosure on January 23. Connecticut has a mandatory mediation program that will prevent the foreclosure from occurring immediately. However, the stress of the situation has led to a further decline in Leong’s health. “She should not be in foreclosure again,” White said.

Any completed foreclosures could trigger payouts from the USDA and HUD’s mortgage insurance funds, costing the government money for no good reason.

Attorneys and housing advocates want the USDA and HUD to extend all foreclosure-related deadlines by 35 days to account for the shutdown. They also want an immediate stay on foreclosures in their programs and extended deadlines for assistance until the backlog is cleared. Finally, all foreclosures executed during the shutdown should be rescinded, they said.

If the government shuts down again, not only would the backlog of cases continue to pile up, but borrowers awaiting an answer on their particular situation would again have no recourse at the USDA or HUD, and find themselves at the mercy of a relentless foreclosure timeline. Many borrowers don’t have attorneys helping them through the intricacies of the system. Low-income rental assistance could also be affected by a renewed shutdown, and if that dries up, substantial numbers of evictions could ensue.

But merely averting a shutdown won’t avert the foreclosure the first shutdown caused.

The post How the Government Shutdown Caused a Foreclosure — and Could Cause More appeared first on The Intercept.

Subscribe to the Intercepted podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, Radio Public, and other platforms. New to podcasting? Click here.

The U.S. is weaponizing humanitarian aid in an effort to sell its regime change campaign against Venezuela. This week on Intercepted: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi officially endorses the attempted coup in Venezuela, joining forces with Donald Trump and his posse of neoconservatives. Venezuela’s Vice Foreign Minister Carlos Ron responds to the threats of military action and the reports about covert U.S. activity in the country. He also discusses the impact of the sanctions on Venezuela. Former United Nations rapporteur Alfred de Zayas is accusing the U.S. of attempting to “asphyxiate” Venezuela with economic warfare and says the U.S. should be investigated by the International Criminal Court. Zayas wrote a U.N. report on Venezuela in late 2018 that was scathing in its assessment of U.S. policy toward Venezuela under both Obama and Trump. He talks about what he found during his investigation. And we go inside the mind of journalist Sam Husseini, who tried to ask convicted criminal Elliott Abrams about his past and the present U.S. lies about Venezuela.

Transcript coming soon.

The post Neoliberalism or Death: The U.S. Economic War Against Venezuela appeared first on The Intercept.

After the foreclosure crisis of a decade ago, American homes were left empty and buyer-less. In that absence, big private investment firms scooped up nearly 200,000 homes under the premise that, as landlords, they could streamline an often shoddy renting process. But, for many of the renters who had thought they had struck gold with lovely homes and lush yards, things didn’t pan out that way. Tenants conveyed stories of rapacious corporate landlords who fleeced them at every turn, from not returning security deposits to forestalling and skirting necessary repairs. One family finally moved out after a series of flooding incidents left them with health problems and a decaying house.

The U.S. government seemed to be careening toward yet another shutdown—but then! Congressional negotiators agreed to a new funding deal, one that only includes a fraction of the billions that President Donald Trump requested for a border wall—the same sticking point that led to a 35-day partial government shutdown starting at the end of last year. While factions of the right-wing media are buzzing in Trump’s ear about a shutdown redux, he so far seems to be taking a different strategy than he did the last time around, indicating that while he doesn’t like the deal, he’ll (likely) vote for it anyways.

Allegations against Bryan Singer finally seem to be turning into an anvil weighing down his reputation and career. The director of Bohemian Rhapsody should be looking forward to the Oscars, where his film is up for Best Picture, but he’s been dogged by an exposé last month that laid out numerous allegations of sexual misconduct over his decades-long career. Despite the maelstrom of negative press, Singer hung on to his gig directing Red Sonja, which was slated to start production later this year, and for which he would have received a reported $10 million paycheck. Now, the company behind the film is putting the project on hiatus (it hadn’t yet secured any financing).

Evening Reads (Hekla / Dasha Petrenko / Goodmood Photo / Shutterstock / The Atlantic)

(Hekla / Dasha Petrenko / Goodmood Photo / Shutterstock / The Atlantic)Since Marie Kondo’s book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up was published in the U.S. in 2014, millions of people have absorbed her lessons on how to declutter and purge their homes of items that don’t bring them happiness. Years after doing the cleanout, most people speak favorably about the experience, though it fosters pangs of regret for some:

“The most missed item in all these purges was a special-edition pack of Pepsi bottles, each emblazoned with a cartoon alligator, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the University of Florida’s football program. The bereaved: Imani Clenance, a 34-year-old graduate of the university who lives in New York City. ‘Every now and then I think about those, like, Hmm, those might’ve been kind of cool to keep … But if I really wanted them, I could probably find them somewhere on eBay,’ Clenance says. (I looked—she could.)”

(Illustration: The Atlantic)

Steven Soderbergh, the director behind films like Ocean’s Eleven and Erin Brokovich , says in an interview with critic David Sims he has “a lot of crackpot theories about how moviegoing has changed and why”:

“One of the most extreme is, I really feel that why people go to the movies has changed since 9/11. My feeling is that what people want when they go to a movie shifted more toward escapist fare. And as a result, most of the more “serious” adult fare, what I would pejoratively refer to as “Oscar bait,” all gets pushed into October, November, December.”

Look Back

(Photo: Warren M. Winterbottom / AP)

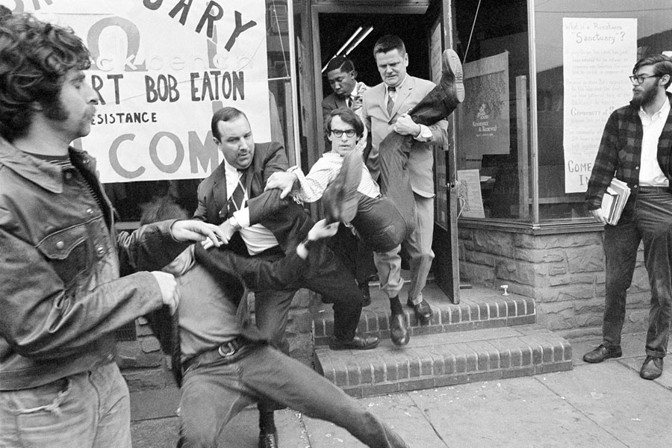

In the above photo, FBI agents carry the Vietnam War draft resister Robert Whittington Eaton, 25, out from a home in Philadelphia, where Eaton had chained himself to 13 young men and women.

Also fifty years ago: Sesame Street premiered, humankind sets foot on the moon, and more. Glimpse more of the global events of 1969, in this gallery from The Atlantic’s photo editor Alan Taylor.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here.

Comments, questions, typos? Email newsletters editor Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

It’s Wednesday, February 13.

The House passed a bill to end U.S. support for Saudi Arabia in the Yemen civil war. It’s essentially the same legislation that passed the Senate back in December, but was never taken up by the House.

Almost Averted: Even though President Donald Trump said he’s not “thrilled” with the bipartisan border-security deal reached by congressional negotiators, he’ll likely give the spending bill his signature anyway. According to multiple sources in the White House and on Capitol Hill, Trump, for the first time, feels as if he has more latitude to act unilaterally to build the wall. That could include rerouting funding from other agencies, or declaring a national emergency. “He’s inclined to sign it and go the executive-action route,” said one House Republican aide.

The deal still needs to pass through both chambers of Congress and receive a signature by the president before midnight on Friday to avoid another government shutdown.

Most Wanted: The U.S. Justice Department charged a former U.S. Air Force counterintelligence officer with revealing classified information about her former colleagues to the Iranian government. The agent, Monica Elfriede Witt, was born and raised in Texas but defected to Iran in 2013.

So Long: The administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Brock Long, resigned from his position after less than two years on the job. Long oversaw the response to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, for which the government is still under heavy scrutiny. He has also been criticized for allegedly misusing government vehicles to travel to his home in North Carolina.

End of an Era: NASA announced that it will stop trying to contact the Opportunity rover, which was sent to Mars 15 years ago to search for signs of life. That leaves only one functioning rover on Mars, Curiosity, which landed on the planet in 2012.

Snapshot

Bacon, an Australian terrier, competes with the terrier group at the 143rd Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show on Tuesday in New York. (Frank Franklin II / AP)

Ideas From The Atlantic

(Image: Library of Congress)

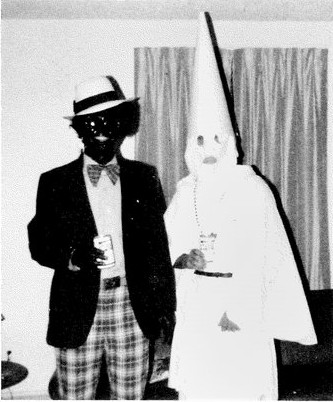

The ‘Loyal Slave’ Photo That Explains the Northam Scandal (Kevin M. Levin)

“The performance of blackface reinforces the belief that blacks smiled through slavery, and later, the post-Reconstruction period of white-supremacist terrorism, on through the indignities of Jim Crow—that these darkest periods of American history were, in fact, not so dark, but joyous times when all people knew their place.” → Read on.

Maria Butina Is Not Unique (Joseph Augustyn)

“The gun-toting Russian graduate student who pleaded guilty in late 2018 to conspiracy to act as an illegal foreign agent creates a media frenzy every time she opens her mouth. Lost in the noise so far, however, is the fact that Butina may be one of many. For years, countries including Russia and China have regarded their citizens who study in the United States as an intelligence-gathering resource.” → Read on.

◆Minnesota Jewish Leaders Talked With Ilhan Omar About Anti-Semitism Last Year. Why They Remain Frustrated. (Dave Orrick, Pioneer Press)

◆ Everyone’s Running—And That Could Be Dangerous for the Democrats (Nate Silver, FiveThirtyEight)

◆ Schumer Recruits Famed Fighter Pilot to Challenge McConnell in 2020 (Alex Isenstadt, Politico)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here. We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

Medias and William, a young couple in rural Uganda, are trying to have a baby—to no avail. They’ve been together a long time, and their options are becoming limited.

“People say, ‘She’s not a woman. She doesn’t have a child,’” Medias says in Paul Szynol’s short documentary, premiering on The Atlantic today. “I try to avoid people because they show me that I’m worthless.”