Is the Mueller investigation in its waning days? After nearly two years and dozens of indictments, some of the lawyers on the team are being reassigned to other positions in the Justice Department. If the investigation is indeed wrapping up, it’s still not quite clear what comes next and what it will portend for the president. The White House doesn’t yet seem to have a full plan on how to deal with the report once it drops, not including President Trump doing what Trump does best—tweeting up a storm.

It’s no shock that wherever you live could be significantly warmer in the coming years. But a new study tries to pinpoint what the conditions in various cities will look like relative to other places today—in other words, their “climate twins.” The effects are drastic, with the average American city moving more than 500 miles away from its current location, making Philadelphia resemble Memphis, New York City into Arkansas, and Minnesota into Kansas.

Last week, Apple delivered a warning that some apps might surreptitiously be recording users’ screens. The app developers in question had consulted with the analytics firm Glassbox to keep track of every button pressed and keyboard stroke entered while inside the app. The company claims that it uses machine learning to troubleshoot bugs and improve the user experience, though the technology could also be a tool to nudge customers into spending more time—and money—on the app.

Evening Reads

(Illustration: Matthew Shipley)

For all those who are getting divorced but can’t afford a divorce lawyer to help wade through the morass of division of assets and debt, child custody and support, and legal paperwork, Deborah Copaken documented her DIY divorce, for which she served as her own representation:

“Suddenly, what should have been an easy day in court became anything but. I quickly Googled 50/50 custody under the table. With precise, down-to-the hour 50/50 custody in New York State, I learned, the higher earner would be responsible for paying child support to the lower earner. Never mind that both of us knew precise 50/50 custody was impossible: I was, had been, and would always be our children’s primary caregiver. This was one of the many issues that tore us apart, the inequity in our domestic responsibilities. My smugness was gone. I longed for a lawyer.”

(Illustration: Getty / Life on White)

Do animals have feelings? Scientists in the West have only recently started to consider that possibility, but in India, that idea is deeply ingrained in the ideology of one religion:

“The bird hospital is one of several built by devotees of Jainism, an ancient religion whose highest commandment forbids violence not only against humans, but also against animals. A series of paintings in the hospital’s lobby illustrates the extremes to which some Jains take this prohibition. In them, a medieval king in blue robes gazes through a palace window at an approaching pigeon, its wing bloodied by the talons of a brown hawk still in pursuit. The king pulls the smaller bird into the palace, infuriating the hawk, which demands replacement for its lost meal, so he slices off his own arm and foot to feed it.”

Urban Developments

(Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

Our partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing urban dwellers around the world. Claire Tran shares today’s top stories:

The Green New Deal, CityLab’s Brentin Mock writes, must empower the people who face the most harm from climate change to help craft local solutions—all while challenging historical legacies of injustice.

The number of unsheltered homeless Americans living in their car is growing. Some cities have started Safe Parking programs to help them, offering bathrooms, security, and other social services.

Historic preservation is usually categorized in a binary way: Either buildings are historically significant, or they are not. That’s too limited, argues Patrice Frey.

Keep up with the most pressing, interesting, and important city stories of the day. Subscribe to the CityLab Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here.

Comments, questions, typos? Email newsletters editor Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

It’s Tuesday, February 12.

Lawmakers announced late Monday night that they had reached a deal to prevent another partial government shutdown. The final agreement includes $1.375 billion for a 55-mile physical barrier on the border, a far cry from the $5.7 billion for a concrete wall that President Donald Trump demanded before the last shutdown. And the president isn’t thrilled: During a Cabinet meeting today, he told reporters that he was “not happy” with the deal and didn’t confirm whether he would sign the new compromise before Friday. But he also said he doesn’t think another shutdown will happen.

A funeral for Representative John Dingell, the longest-serving member of Congress in American history, was held today in Michigan. Former Vice President Joe Biden delivered a speech at the funeral. A second memorial will be held for the former lawmaker later this week in Washington, D.C.

Noticeably Absent: Not one, but two efforts are under way to reach peace in Afghanistan, one of which is being facilitated by the United States. But the Afghan government isn’t at the negotiating table in either of them, reports Krishnadev Calamur.

Twin Cities: A new study found that by 2080, global warming will make American cities feel as if they’ve moved more than 500 miles toward the south or interior of the country. Imagine if New York City felt like Jonesboro, Arkansas. What will your home city’s 2080 climate-change twin be?

The Last Impeachment: It’s the 20th anniversary of former President Bill Clinton’s acquittal in the Senate. The biggest players of the moment recounted their memories of the impeachment, and the scandalous events leading up to it, for The Atlantic’s December issue.

— Madeleine Carlisle and Olivia Paschal

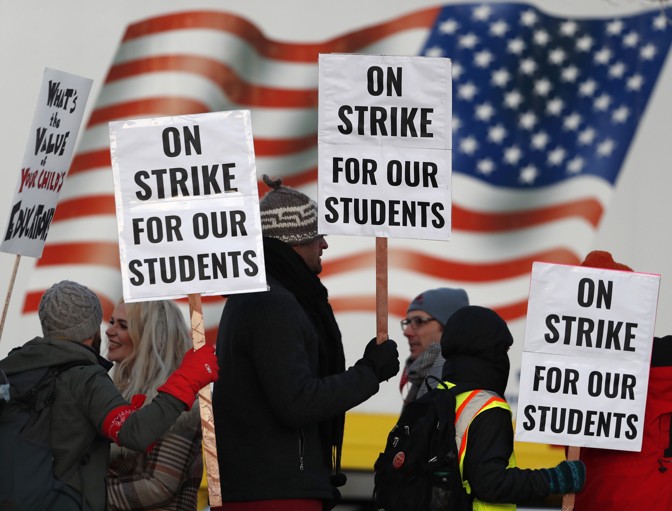

Snapshot

Teachers walk a picket line outside South High School early Monday, in Denver, Colorado. (AP Photo / David Zalubowski)

Ideas From The AtlanticThe Much-Heralded End of the Mueller Investigation (Mikhaila Fogel and Benjamin Wittes)

“But there’s actually a bigger problem than the possibility that all this eager Mueller-is-wrapping-up chatter may be wrong, just the latest instance of overly hasty anticipation of the Muellerpocalypse: No one knows what Mueller’s ‘wrapping up’ actually means.” → Read on.

A Reading List for Ralph Northam (Ibram X. Kendi)

“This list is for people beginning their anti-racist journey after a lifetime of defensively saying, ‘I’m not a racist’ or ‘I can’t be a racist.’ Beginning after a lifetime of assuring themselves only bad people can be racist.” → Read on.

The U.S. Doesn’t Deserve the World Bank Presidency (Annie Lowrey)

“American control over the bank is an unjustifiable tradition that harms the institution. Self-determination and a truly meritocratic process for choosing its leadership would be good for the bank, and for the world. It is not a case the Trump administration seems to have any interest in entertaining.” → Read on.

One Cheer for Maine’s Task Force on Police Killings (Conor Friedersdorf)

“A task force with more investigatory resources, a broader mandate, and more members willing to ask tough questions about police tactics could do useful work, if elected officials in Maine ever see fit to underwrite one. Meanwhile, many states are doing even less to study the problem than Maine.” → Read on.

◆ It’s Christian Politics, Not AIPAC Money, That Explains American Support for Israel (Sam Goldman, The Washington Post)

◆ The Complicated, Always Racist History of Blackface (Sean Illing, Vox)

◆ Border Report: The U.S. Is Sending Asylum-Seekers Back to Uncertainty in Mexico (Maya Srikrishnan, Voice of San Diego)

◆ Federal Shutdowns Cut Deep in Indian Country (Keerthi Vedantham, High Country News)

◆ San Francisco’s Accidental Surveillance State and the Future of Privacy (J. D. Tuccille, Reason)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here. We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

In January, The Atlantic published an investigation into several allegations of sexual misconduct against the filmmaker Bryan Singer, who’s directed many blockbusters in his long career, including the recent box-office sensation Bohemian Rhapsody. The news reverberated throughout Hollywood. But one producer who seemed untroubled was Avi Lerner. As the CEO of Millennium Films, Lerner was responsible for high-budget shlock such as the Expendables series, Olympus Has Fallen and its sequels, and an upcoming remake of Red Sonja, which had just hired Singer for a reported $10 million. This week, Deadline reported that the film was being moved to the “back burner” and taken off Millennium’s development slate.

Singer has dismissed the Atlantic’s story as a “homophobic smear piece,” calling the accusations “bogus.” Lerner backed him up in a January 24 statement, saying, “I know the difference between agenda-driven fake news and reality, and I am very comfortable with this decision. In America people are innocent until proven otherwise.” Less than three weeks later, things have changed: On Monday, Deadline reported that Red Sonja is being taken out of active development by its studio, which had been planning to start production in Europe later this year. Perhaps Singer’s reputation in Hollywood has now become too toxic even for Millennium Films. (Lerner was not immediately available for comment.)

For years, rumors had swirled in the industry about alleged sexual misconduct by Singer (fueled by several lawsuits, many of them dismissed for various reasons) and about his on-set behavior, with reports of clashes with other actors and persistent lateness. According to The Hollywood Reporter, before Singer was approved by Fox to direct Bohemian Rhapsody, the studio head Stacey Snider warned him not to break the law and to show up to work every day—an extraordinary demand to make of a person in charge of a $55 million project. But according to Fox, Singer failed to comply, and the studio fired him before production was complete (Directors Guild rules mandate that Singer retain the director credit).

[Read: ‘Nobody is going to believe you’]

Why would anyone be in line for a $10 million paycheck after such an experience? Lerner’s initial defense was that the movie Singer got fired from was still a commercial hit. “The over $800 million Bohemian Rhapsody has grossed, making it the highest-grossing drama in film history, is testament to his remarkable vision and acumen,” Lerner said in a statement. It’s worth noting that while Singer has directed many hits, he’s also overseen financial disappointments: 2013’s Jack the Giant Slayer was a notorious bomb, losing a reported $140 million for its studio, while his Superman Returns performed worse than expected, failing to produce a sequel and burdened by a staggering $200 million-plus budget.

Singer certainly doesn’t deserve sole credit for Bohemian Rhapsody’s success; the high grosses are at least partly thanks to the enduring popularity of the band Queen, one of the best-selling musical acts of all time. On the other hand, Red Sonja, a reboot of a Brigitte Nielsen–starring action drama that made $6.9 million in 1985, is a much more marginal property. Lerner and Millennium Films had not even secured financing for the project yet, and the company was looking to attract investors this month at the European Film Market, an annual gathering of movie-business operatives attached to the Berlin Film Festival. At the best of times, a Red Sonja revival might not be the hottest title at EFM; with Singer’s name attached, arguably no sage investor would jump on board.

Hence the apparent step back. Singer hasn’t been officially removed from the movie, but without any funding, cast announcements, or immediate plans to begin filming, the project essentially doesn’t exist. Lerner, for his part, has only somewhat backtracked on his original statement in defense of Singer, telling Deadline that his comments “came out the wrong way,” and that “I think victims should be heard and this allegation should be taken very, very seriously … I just don’t agree to judge by Twitter. I want [the accused] to be judged by the court.”

Lerner has his own experience with high-profile misconduct allegations. The actor Terry Crews told a Senate panel last year that Lerner had threatened to fire him from the fourth Expendables movie if Crews didn’t drop a sexual-harassment case against the Hollywood agent Adam Venit. (Lerner told The Hollywood Reporter that he was simply asking for “some kind of peace.”) In 2017, Lerner was sued by a former employee who alleged sexual harassment by the CEO and other top-level employees, gender discrimination, and the fostering of a hostile work environment. (Lerner called the suit “all lies” and “a joke.”) “Abusers protect abusers,” Crews told senators, recounting Lerner’s alleged intervention on behalf of Venit. But despite Lerner’s initial efforts to defend Singer, the shelving of Red Sonja suggests that the director’s reputation could finally be a meaningful roadblock for his career in Hollywood.

This year’s 143rd annual Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show is hosting 2,800 dogs, consisting of more than 200 different breeds or varieties. Below are images from the two-day competition and preliminary activities held in New York City at Piers 92/94 and Madison Square Garden. And, for a closer look at the road to Westminster and the life of a show-dog breeder, please read “Backstage at the Westminster Dog Show,” by Ashley Fetters.

Sarah Krebs is used to corpses going missing. As a detective who works in the missing-persons unit in Detroit, she has solved dozens of cases by matching up disappeared people to unidentified bodies left in state custody. But for older cases in which the county was supposed to have buried the body, Krebs says it’s common for her to order an exhumation from the local cemetery and discover that the body she’s looking for is not there.

Anywhere from a few days to a few years later, those bones might turn up in a separate burial plot, or in a box on a medical examiner’s shelf, or in a law-enforcement evidence room, or in a county employee’s house. “I have multiple, multiple cases where we thought the body was buried and we found a couple days later that someone had it at home,” Krebs says.

The reason for this morbid confusion is that the United States is enduring a cadaver pileup. Medical examiners around the country are being overrun with bodies that no one comes to pick up, a trend that many coroners attribute to the nation’s opioid epidemic. Drug-overdose deaths increased by 10 percent from 2016 to 2017, largely driven by fentanyls and similar drugs, according to the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. Now medical examiners in cities such as Detroit process dozens of new remains each day. And as Krebs has encountered, some of those bodies can slip under the radar.

[Read: What happens to a dead body no one can name?]

The bodies that remain accounted for, meanwhile, float in and out of state custody. No one is quite sure what to do with them. The United States has no uniform system for managing the unclaimed. There is no federal law outlining what steps to take, and many states do not have clear procedures, leaving individual medical examiners to make decisions about how to best deal with the bodies. As a result, examiners without money to simply bury or cremate the remains are resorting to inventive—and strange—solutions.

Among the unclaimed bodies processed in the United States, some are the unidentified remains from missing-persons cases like the ones Krebs works on, but the majority belong to people who were estranged from their family while they were alive, according to Kenna Quinet, an associate professor at Indiana University—Purdue University Indianapolis who co-wrote one of the only academic articles on unclaimed bodies. In most of these cases, the identity of the victim is known, but coroners or funeral directors can’t contact the next of kin, or the next of kin was reached and either doesn’t want the body or can’t afford to bury it. The unclaimed population skews poor and homeless.

Policy makers have rarely backed programs that would set clear terms for the management of the unclaimed, which has left coroners to cycle through a grab bag of disposition methods once a body enters their custody. Coroners often opt to cremate unclaimed remains to save money—burials cost at least twice as much—but some states don’t allow coroners to request a cremation for fear that it could infringe on the deceased’s religious values. In smaller counties that have fewer unclaimed bodies, bodies are kept in coolers; those that are cremated are left in boxes or in a coroner’s closet.

Los Angeles County has one of the more organized systems. There, unclaimed bodies are cremated if no one comes to retrieve them within a month of death, after which the cremains are kept in the county coroner’s office for another three years, according to the Los Angeles Times. If by that point no family has reached out, the cremains are buried alongside more than a thousand others in an annual interfaith funeral.

But because of a lack of funding, counties cannot always afford to pay funeral directors to cremate or bury unclaimed bodies. Only 14 states devote money to funeral costs for unclaimed bodies, and it rarely covers the actual volume of bodies that coroners and funeral directors face. West Virginia, which has the highest rate of opioid deaths in the United States, has run out of funds two years in a row, the state’s Funeral Directors Association told me. And while some counties and towns provide funds in addition to the state’s contribution, many don’t.

That has left cash-poor cities like Detroit to scatter remains in haphazard ways. Shortly after the financial crisis, according to Krebs, the county medical examiner stashed unclaimed bodies in a refrigerated semitrailer in a back parking lot, a last resort usually reserved for disasters like Hurricane Maria. Two funeral homes the City contracted with are currently under investigation after some bodies were found unburied. When unclaimed bodies are in fact buried, Krebs says, the process is cheap and unglamorous: In some cases, cemetery workers have “dug a trench and lined up body bags.”

Other cities have similarly drawn ire over their burial of the unclaimed. In 2015, Washington, D.C., discovered that, in some cases, the funeral home that the City paid to bury its unclaimed bodies had simply dumped the remains in unmarked graves beside trash cans. (The funeral home claimed that it followed the terms of its contract.)

Placing even more strain on medical examiners is the fact that a centuries-old method for clearing out unclaimed bodies—donating them to medical schools—is often no longer viable. Many states have long relied on donations, a tradition that surfaced in the 19th century following a series of riots against the then-common practice of robbing graves to supply bodies for anatomy research. The resulting Anatomy Acts, which passed in many U.S. states in 1831 and 1832, allowed medical schools to dissect “unclaimed bodies.” But as the historian Michael Sappol has written, many of these bodies were simply people who couldn’t afford burials. New York banned unclaimed-body donations in 2016 after an outcry, and even in states where handing over unclaimed bodies is legal, many medical schools now refuse to take them.

All this means that solutions for managing the dead are getting weirder and more controversial—though not necessarily worse. While Tennessee gives some unclaimed cadavers to “body farms” where researchers study decomposition, New York has buried more than 1 million unclaimed bodies on its inaccessible Hart Island, a 100-acre strip of land north of Manhattan. States such as North Carolina cremate unclaimed remains and scatter them at sea. Dallas, which is also overrun with unclaimed bodies, briefly debated liquefying remains through an environmentally friendly process known as alkaline hydrolysis. That initiative failed after lawmakers expressed revulsion for the technique, which reduces human bodies to a brownish liquid and a set of bones.

[Read: How to be eco-friendly when you’re dead]

In the meantime, some people are attempting to limit the number of bodies that go unclaimed in the first place. NamUs, a federal missing-persons database that has recently expanded to include unclaimed bodies, for instance, is attempting to make it easier for medical examiners to match unclaimed remains to missing persons. According to NamUs’s communication and case-management director, J. Todd Matthews, unclaimed bodies are often reported missing in a state other than where they actually died, but medical examiners don’t have direct access to the National Crime Information Center’s missing-person database. NamUs hopes its own database can provide an alternative search tool when medical examiners wind up with bodies whose family they can’t locate.

Still, many medical examiners don’t know NamUs exists, according to Matthews. Until any sort of procedure is standardized, unclaimed bodies in cities that see a high number of dead will continue to float from office to office, home to home, refrigerated truck to refrigerated truck. When Krebs needs to test the DNA of an unclaimed body for a missing-persons case, she will have to keep racing from building to building in search of the transient dead. And she won’t be surprised to find the bones she has been looking for in a glass display at a local university. She’s solved cold cases that way.

Sixty years from now, climate change could transform the East Coast into the Gulf Coast. It will move Minnesota to Kansas, turn Tulsa into Texas, and hoist Houston into Mexico. Even Oregonians might ooze out of their damp, chilly corner and find themselves carried to the central valley of California.

These changes won’t happen literally, of course—but that doesn’t make them any less real. A new paper tries to find the climate-change twin city for hundreds of places across the United States: the city whose modern-day weather gives the best clue to what conditions will feel like in 2080. It finds that the effects of global warming will be like relocating American cities more than 500 miles away from their current location, on average, mostly to the south and toward the country’s interior.

[Read: The American South will bear the worst of climate change’s costs]

For instance, the Philadelphia of the 2080s will resemble the historical climate of Memphis. By the time kids today near retirement age, Philadelphia’s average summer will be about 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than it is now. Winters in Philly will be nearly 10 degrees more temperate. Memphis’s scorching, sticky weather provides the best guide to how those climatic changes will feel day after day.

Meanwhile, Memphis’s climate will come to resemble that of modern-day College Station, Texas, by 2080.

A screenshot of the new tool from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. (Fitzpatrick et al. / UMCES)

A screenshot of the new tool from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. (Fitzpatrick et al. / UMCES)The paper was accompanied by the release of a new tool that lets Americans find their city’s climate-change twin.

“Everything gets warmer,” says Matthew Fitzpatrick, an author of the paper and a professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “I don’t think I’ve seen a place that doesn’t.” In the West and Midwest, cities also tend to get drier as the Great Plains shift east. So Chicago comes to Kansas, Denver drifts to Texas, and San Francisco starts to feel like Los Angeles.

Read: [The three most chilling conclusions from the climate report]

Fitzpatrick cautions that no city will perfectly match its climate twin, especially when it comes to rainfall. Many cities in the South simply do not have a good twin: “The climate of many urban areas could become unlike anything present” in North America, the paper says.

In the Northeast, you can envision the future as one big Arkansas-ification. The paper finds that if the world meets its goals under the Paris Agreement, then Washington, D.C., will enter the 2080s feeling a lot like Paragould, Arkansas. But if the world follows a worst-case scenario, then D.C. will more closely resemble northern Mississippi—and New York City will feel like Jonesboro, Arkansas.

That worries Virginie Rolland, a resident of Jonesboro and a professor of ecology at Arkansas State University. “That’s in line with what I know, that the eastern U.S. will become hotter and wetter, while the [Midwest] will become drier and hotter,” she told me. Her own research focuses on eastern bluebirds, which have historically spent the summer in New York before migrating south for the winter. But “they’ve started staying in New York” for the winter, she said, “so I know it’s getting warmer there.”

She also warned future New Yorkers about what Jonesboro has in store: “Summer-wise, it’s like Florida here. And I cannot imagine New York like Florida … it’s hard to think about how humid it will be.”

Read: [The new politics of climate change]

“I wouldn’t wish the hot and humid summer climate of Arkansas on anyone,” agreed David Stahle, a climate scientist at the University of Arkansas, in an email.

“I was shocked, to be honest,” at how southerly many cities would soon feel, Fitzpatrick told me. The research spun out of his own weather worries: “I really like snow, and I thought, Is that still going to happen up here?” he said. But when he looked up his current home in Cumberland, Maryland, he found that it would soon feel like southern Kentucky. He groaned. “I lived in Knoxville for several years, in central Tennessee, when I was doing my Ph.D., and I couldn’t wait to get out of there because it was so hot and humid. I thought, Ugh, the climate’s following me up here.”

Even though Fitzpatrick works with climate data all the time—and knew, as he put it, that “it’s gonna get warmer, whatever”—he had never thought about it like this. “If I have grandkids and they lived in the same place I do,” he said, “they might not recognize this climate that we’re living in now.”

The romantic comedy has been in a state of moderate crisis for the better part of a decade. After spending the early aughts making easy money with pairings of largely interchangeable stars—Kate Hudson, Matthew McConaughey, Katherine Heigl, Hugh Grant, Drew Barrymore, Adam Sandler, Jennifer Lopez … —rom-coms saw their box-office wave dry up abruptly around 2012. As the producer Lynda Obst, a doyenne of the genre, told Vulture that year, “It is the hardest time of my 30 years in the business.”

Some rom-coms began experimenting with out-there premises (the “She’s a woman, he’s a zombie” setup of Warm Bodies), while others presented themselves as another genre altogether (Silver Linings Playbook, for instance, or Moonrise Kingdom). Lately, many of the more successful entrants in the genre have been films that de-emphasized Hollywood movie stars and featured racially diverse casts (The Big Sick, Crazy Rich Asians, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before). But I think it’s safe to say that we are at a moment when no one has a particularly good sense of precisely where the rom-com is headed.

Into this cinematic breach steps Isn’t It Romantic, a would-be high-concept Rebel Wilson film that intends to revivify the romantic comedy by satirizing it. I am sorry (though unsurprised) to report that it does not succeed.

The movie opens to the song “Oh, Pretty Woman” and, moments later, to the movie Pretty Woman, which a slightly chubby Australian girl named Natalie is watching on TV. Her mother (a vastly underutilized Jennifer Saunders) warns the blissed-out child to “forget about love.” No one will ever make movies about “girls like us,” she explains, adding, “Someone might marry you for a visa, but that’s about it.”

Flash forward, and the now grown Natalie (Wilson) is an architect at a Manhattan firm. Sadly, her mother’s warnings about how no one will be interested in her appear to have come true, both romantically and professionally. Despite her career success, everyone in the office treats Natalie like a coffee girl. Even her best friend, Josh (Adam DeVine, Wilson’s co-star and eventual squeeze in the Pitch Perfect movies), seems to spend his days looking out the window at a billboard of a bathing-suited supermodel. Gone are the romantic fantasies of Natalie’s girlhood. She even berates her assistant, Whitney (Betty Gilpin), for enjoying rom-coms, and proceeds to enumerate all the tedious tropes thereof: the adorably clumsy lead, her gay best friend, her female nemesis, the cheesy pop songs, the interruption of a marriage to the Wrong Person. (Take notes. As you’ve probably surmised, these will be important later on.)

In the subway, a man seems to flirt with Natalie. But no! He’s only trying to get close enough to punch her in the stomach in order to steal her purse. (This is one of those movies with the message “What matters is what’s on the inside” that nonetheless tries to get as much early comic mileage as possible by making fun of how its protagonist looks on the outside.) In the fracas, Natalie bangs her head against a steel beam and passes out. When she awakens, she finds herself in a romantic comedy. All of the aforementioned tropes are in evidence; every good-looking guy is now more interested in her person than in her purse; etc., etc. Even New York “doesn’t smell like shit anymore!,” Natalie enthuses.

If this sounds an awful lot like last year’s Amy Schumer vehicle, I Feel Pretty (in which Schumer bangs her head and comes to believe that she is the most beautiful woman in the world), well, that’s because it is. Yes, it appears we now have an official subgenre of pseudo-feminist movies in which a woman is initially presented as completely unattractive; is concussed into a fantasy in which she becomes impossibly desirable; and from the experience gleans important, affirmative lessons about believing in herself.

[Read: When beauty is a troll]

Sigh. At least Isn’t It Romantic is not as sour and self-negating as Schumer’s film (which was already an improvement on its genre cousin, Shallow Hal). The new movie, directed by the comedy journeyman Todd Strauss-Schulson, offers flashes of charm here and there, and a couple of modestly fun musical numbers. But its moral messages are frequently confused or contradictory, and the movie is neither particularly funny nor particularly clever in its dissection of the rom-com genre.

Natalie stumbles (literally stumbles) into the Perfect Guy, a handsomely bearded billionaire played by the youngest Hemsworth brother, Liam. Likewise, Natalie’s sweet-natured friend Josh ends up dating the very same supermodel and “yoga ambassador” (Priyanka Chopra) from the swimsuit billboard. Will these two mismatched couples find enduring love? If you don’t already know the answer to that question, then you clearly have not seen enough rom-coms. Isn’t It Romantic ends precisely the way you assume it will by the movie’s second scene.

Along the way, there are plenty of references to Pretty Woman, as well as nods—some better than others—to The Wedding Singer, When Harry Met Sally, Jerry Maguire, Notting Hill, Sweet Home Alabama, She’s All That, and doubtless others that I’m forgetting. And Natalie of course acquires a gay friend (Brandon Scott Jones), who is written as swishily as any 1980s-movie caricature. The filmmakers evidently believe that if an unpleasant comic stereotype is presented with a touch of irony, it will somehow be rendered no longer unpleasant.

This is of a piece with the movie itself, which consistently wants to have it both ways. It’s true that it is no easy feat to succeed as both a romantic comedy and a send-up of romantic comedies. Alas, Isn’t It Romantic fails on both counts.

NEW YORK, N.Y.— On ordinary days, Mara Flood and her 18-year-old daughter, Becca Flood, interact like any other mother and daughter might, but on days like today, they’re more like colleagues—and rivals. The Floods, who breed and handle smooth collies together, have brought their dogs Cherry (whose full name is SugarNSpice Cherry On Top), Poe (Travler SugarNSpice Witches Do Come Blue), and Tiger (SugarNSpice Hear Me Roar) from Orange County, New York, to Manhattan to compete in Monday’s events at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show.

Becca and Mara came to Pier 94, on the west side of the city, on Sunday afternoon to set up their dogs’ grooming tables and then have dinner out together in the city (their annual pre-Westminster tradition). Monday’s workday started at 5:30 a.m., when Mara began bathing the dogs and then woke up Becca to ask her to start blow-drying them. And then at noon, the two Floods faced off against each other (and seven other handlers, one of whom was showing Cherry) in the Best of Breed competition, five-year-old Tiger at the end of Mara’s lead and two-year-old Poe at the end of Becca’s.

Mara, whose female dog Gretel won Best of Breed in 2016 at Westminster, wanted to win it again. This time, though, she says, Poe was a little squirrelly in the ring, and Tiger faced stiff competition from the other females. In the end, Tiger and Poe took home the Best of Opposite Sex and Select Dog titles, respectively; in other words, they placed second and third behind the dog who eventually went on to compete in the Herding Group round at Madison Square Garden.

“You’re always hoping to win Best, and you never, until you walk into that ring and get a ribbon, know how it’s gonna go,” Mara said later. “But we’re thrilled with what we got. Our dogs went in there and they showed well, and you can’t ask for more than that.”

Owners and handlers groom their dogs in the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show “benching area” at Pier 94 in Manhattan. A “benched” dog show is one in which each dog is required to be in its designated berth on the grounds for the entirety of the event unless it is showing, being groomed to show, or out for a brief walk, so that visitors and other exhibitors can stop by and observe them.

Owners and handlers groom their dogs in the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show “benching area” at Pier 94 in Manhattan. A “benched” dog show is one in which each dog is required to be in its designated berth on the grounds for the entirety of the event unless it is showing, being groomed to show, or out for a brief walk, so that visitors and other exhibitors can stop by and observe them. Two Old English sheepdogs relax in their section of the benching area. On a normal show day, it takes two hours to groom each one. Today, each dog requires four.

Two Old English sheepdogs relax in their section of the benching area. On a normal show day, it takes two hours to groom each one. Today, each dog requires four. Becca and Mara’s dog-show tack box is divided into two sections—one for the humans’ grooming supplies, and one for the dogs’. Of course, when they’re in a hurry, Becca says, every now and again she and her dogs end up sharing hair mousse or a brush. “I just try to pull out all the dog hair I can before I use it,” she laughs.

Becca and Mara’s dog-show tack box is divided into two sections—one for the humans’ grooming supplies, and one for the dogs’. Of course, when they’re in a hurry, Becca says, every now and again she and her dogs end up sharing hair mousse or a brush. “I just try to pull out all the dog hair I can before I use it,” she laughs. On show days, the Floods bring along seasoned chicken, hot dogs, and steak to use as “bait,” or treats to reward their dogs’ good behavior—and hold their attention—in the ring.

On show days, the Floods bring along seasoned chicken, hot dogs, and steak to use as “bait,” or treats to reward their dogs’ good behavior—and hold their attention—in the ring. Becca shares a piece of a pretzel (her “stress eating” snack between ring times, she says) with Tiger.

Becca shares a piece of a pretzel (her “stress eating” snack between ring times, she says) with Tiger. After changing into her suit, Becca puts on her armband, which helps judges and record-keepers identify her in the ring. Handlers often coordinate what they wear in the ring to complement and contrast with the coat color of the dog they’re showing; it’s important, Mara explains, that the silhouette of the dog always be distinct from the human’s as they run around the ring together.

After changing into her suit, Becca puts on her armband, which helps judges and record-keepers identify her in the ring. Handlers often coordinate what they wear in the ring to complement and contrast with the coat color of the dog they’re showing; it’s important, Mara explains, that the silhouette of the dog always be distinct from the human’s as they run around the ring together. Mara and Becca groom Tiger, taking special care to fluff up the fur around her neck. “It just gives the dogs more presence,” Becca says. Later, as the two waited for their dogs’ turn in the ring, they sprayed down the dogs’ backs with water to keep their fur from drying out and flattening under the hot indoor lights.

Mara and Becca groom Tiger, taking special care to fluff up the fur around her neck. “It just gives the dogs more presence,” Becca says. Later, as the two waited for their dogs’ turn in the ring, they sprayed down the dogs’ backs with water to keep their fur from drying out and flattening under the hot indoor lights. Left: Every year before they show their dogs at Westminster, the Floods get manicures together. Usually they do some variation on the official colors of Westminster, purple and gold. Right: A handler discreetly carries a brush into the ring to facilitate any necessary last-minute grooming.

Left: Every year before they show their dogs at Westminster, the Floods get manicures together. Usually they do some variation on the official colors of Westminster, purple and gold. Right: A handler discreetly carries a brush into the ring to facilitate any necessary last-minute grooming. Becca participates in her last-ever junior showmanship competition. In general, competitors age out of juniors when they turn 18, but Becca qualified for this year’s Westminster juniors event before her birthday.

Becca participates in her last-ever junior showmanship competition. In general, competitors age out of juniors when they turn 18, but Becca qualified for this year’s Westminster juniors event before her birthday. Left: A rough collie—a longer-haired collie variety, so closely related to the smooth collie that sometimes rough and smooth collies are born in the same litter—gets groomed in the benching area. Right: A handler wears a collie tie clip.

Left: A rough collie—a longer-haired collie variety, so closely related to the smooth collie that sometimes rough and smooth collies are born in the same litter—gets groomed in the benching area. Right: A handler wears a collie tie clip. A Neapolitan mastiff hangs out in the Westminster benching area.

A Neapolitan mastiff hangs out in the Westminster benching area. A Pomeranian gets groomed in the benching area.

A Pomeranian gets groomed in the benching area. The Floods’ dogs—from left to right, Cherry, Poe, and Tiger—took home Winners Bitch, Select Dog, and Best of Opposite Sex titles within the smooth collie breed, respectively.

The Floods’ dogs—from left to right, Cherry, Poe, and Tiger—took home Winners Bitch, Select Dog, and Best of Opposite Sex titles within the smooth collie breed, respectively.In Maine, police officers who use deadly force on the job are always justified in doing so—or at least that’s apparently the official position of the state attorney general’s office, where every deadly police shooting for the past 28 years has been dutifully reviewed, and the cops have always been found justified in their killings. Does that seem plausible?

Last year, after a spike in police killings, the Bangor Daily News editorialized that “this 100 percent justification rate rightly raises a lot of eyebrows,” and commended Maine Attorney General Janet Mills for announcing that she would convene a task force to look into “these deadly encounters.”

The task force’s report, released late last month, encompasses just 10 deadly force incidents. The final product isn’t as thorough in scope or as detailed in what it documents as criminal-justice reformers might wish. Law enforcement is arguably overrepresented among the members of the review team. And its heavy reliance on official records and lack of attempts to interview witnesses rendered it unable to discover any flaws in bygone reviews. But the report is still better than nothing. It attempts to identify and record “common elements or characteristics in these use-of-deadly-force incidents,” something that wasn’t previously done at all.

All of the 10 people killed were armed—seven with guns, two with knives, one with a weapon “consisting of railroad spikes attached to one end of a rope.”

The most striking findings:

“Of the ten cases reviewed … eight of the individuals were living with mental health challenges. In seven of those individuals, family and friends noted signs of depression or depression formally diagnosed. In only two cases was there evidence to suggest that the individuals were receiving treatment for their mental health challenges. In those cases, the individuals were receiving intensive services and supervision of their mental health concerns, including counseling, case management, and community supervision.” “In seven of the cases reviewed, the involved individuals had made statements indicating they were having suicidal ideation at the time, or prior to, the incident. In two cases, individuals had a history of actual suicide attempts.” “In seven of the incidents, involved individuals had either alcohol or drugs in their system at the time of the incident. More specifically, the average Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) of the individuals involved was 0.241%, with three individuals having a BAC of 0.30% or higher, and one having a BAC of 0.43%.” “... six of the individuals had been involved in domestic violence-related incidents.”The report’s conclusion underscored a flaw in the way that most jurisdictions in America respond to police killings: with inadequate efforts to collect information that might help to diagnose root causes or reduce the likelihood of future incidents. Or, as the task force diplomatically put it, “Because of the narrow scope of the Attorney General’s criminal investigation focusing on criminal liability, as well as the narrow scope of the Medical Examiner’s investigation, focusing on determining cause and manner of death, the task force did not have enough information to determine whether the individuals, or their family or friends had attempted to seek treatment for mental health or substance use issues.”

The task force ought to have been charged with gathering that information. Given a sample size of 10 killings, the work hardly seems like too much to reasonably undertake.

Most of the report’s 10 recommendations touched on mental health. The task force urged “access to mental health services, particularly the availability of forensic, crisis and crisis stabilization beds,” more frequent use of “multidisciplinary teams that provide intensive support and supervision of individuals with serious and persistent mental illness,” more collaborative work between police departments and the families of individuals with a serious mental illness, better training for cops “responding to calls for service where there is evidence a person is living with a mental health or substance use disorder,” better training for police dispatchers “in mental health, substance use, developmental disabilities, other vulnerable populations, and crisis response,” and the permanent addition of a “licensed mental health or substance use clinician” to the state’s Use of Deadly Force Internal Review Panel.

The task force’s focus on mental illness is defensible—at least in the popular imagination, it is an undervalued factor in police killings in the United States. Still, fixing the problem will require going much further than the task force did.

Maine’s population is roughly 1.3 million. In the two-year period that the task force says it reviewed, deadly force was used in the state about as often as it was over the same period in Germany, where there are 82.8 million people, including its share of knife-wielders, alcohol abusers, and the mentally ill. Germany differs in the proportion of its residents with guns and the attitudes and approaches of its cops. Both factors must loom larger in any realistic analysis of why U.S. police officers kill so many people, compared with police in other democracies.

A task force with more investigatory resources, a broader mandate, and more members willing to ask tough questions about police tactics could do useful work, if elected officials in Maine ever see fit to underwrite one. Meanwhile, many states are doing even less to study the problem than Maine.

Everyone is saying it: The Mueller investigation is winding down. The acting attorney general declared the investigation “close to completion” during a press conference. His wife, Marci Whitaker, has also insisted that the special counsel’s investigation is “wrapping up.” President Donald Trump’s nominee for attorney general, William Barr, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that, given his public actions, Mueller is “well along” in his investigation.

The press is buying it. NBC says we could be looking at “mid-February” for a delivery of the so-called Mueller report; that would be, well, now. Yahoo! News reported that the probe could be “coming to its climax potentially within a few weeks”—a few weeks ago.

There have also been reports that Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who has been overseeing the investigation, will likely step down soon, but only after the completion of the Mueller probe.

Other sheep entrails and tea leaves are signaling the end as well. Certain investigators in the special counsel’s office are being reassigned to other offices within the Justice Department. There are now only 12, as the president has said, “angry Democrats” (translation: lawyers) working on the Mueller team. (Peter Carr, a spokesman for Robert Mueller, listed the 12 lawyers on Mueller’s staff in an email this morning, along with two attorneys who are still representing the special counsel’s office on specific matters, despite having been reassigned to other Justice Department components.) We are also seeing a migration of investigations into the president’s conduct from the special counsel’s office to other Department of Justice offices, most notably the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Southern District of New York, and the proliferation of new investigations entirely outside the special counsel’s domain.

[Quinta Jurecic: A confederacy of grift]

Yes, some of the sheep guts are pointing in other directions, too. In January, Mueller extended the grand jury investigating l’affaire russe for an additional six months. The prosecutors are dealing with pending litigation, most notably the Andrew Miller and the mysterious Sealed v. Sealed grand-jury cases, not to mention ongoing prosecutions such as the newly filed Roger Stone case. And there are likely outstanding, yet-to-be-filed criminal matters in the Mueller probe as well; Jerome Corsi—who, by his own admission, was offered a plea agreement by the special counsel in November and proceeded to disclose that agreement to the press—has not yet been charged. Of course, remember that Mueller was going to be finished “shortly after Thanksgiving”—that is, Thanksgiving 2017—before he was going to be finished by or around January 1, 2018, before he was going to be finished by June 2018, before he was going to be finished by mid-February.

But there’s actually a bigger problem than the possibility that all this eager Mueller-is-wrapping-up chatter may be wrong, just the latest instance of overly hasty anticipation of the Muellerpocalypse: No one knows what Mueller’s “wrapping up” actually means.

Consider your own reaction to the news: When you learned that Mueller was wrapping up, did you immediately assume that meant things were coming to a confrontation, or did you assume it meant the president was getting away with everything? Did you assume it meant that Mueller’s investigation was petering out and that he would file some kind of report? That he would “clear” the president? That he would produce a dramatic spree of final indictments? Or did you assume it meant that Mueller was getting ready to issue some kind of devastating written work product that ends up driving an impeachment? All of these are consistent with “wrapping up,” but they are radically different outcomes.

It seems a bit weird to speculate breathlessly that we are careening toward some kind of finality without actually knowing either whether the endpoint is near or what we mean when we say that we are reaching it. But for what it’s worth, here are a few possibilities of what it could mean that Mueller is winding down—assuming that he is, in fact, winding down.

First, there’s a kind of commonsense understanding of the term, under which the scope of the work is nearly complete, with the exception of a few investigative loose ends that will take a little bit of time to tie up. The scope of the investigation, as stated in the appointment order issued by Rosenstein on May 17, 2017, includes:

(i) any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump; and

(ii) any matter that arose or may arise directly from the investigation; and

(iii) any other matters within the scope of 28 C.F.R. § 600.4(a) [which governs the jurisdiction of special counsels]

Rosenstein issued a second memorandum, a partially redacted version of which has become public, that clarified that Mueller’s mandate includes allowing him to investigate and prosecute certain activities of the former Trump-campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

[Read: The White House has no plan for confronting the Mueller report]

So if you imagine that “wrapping up” means this first option, then Mueller and his team have largely finished probing the story of the links and coordination between individuals associated with the Trump campaign and the Russian government. They have largely finished investigating efforts to obstruct the probe. And they are probably spinning off the matters that arose in the course of investigating these core things. Yes, there are still issues to be resolved, but those issues are squarely within the realm of what can be gleaned from filed documents. Some of these might include examining newly seized evidence from Roger Stone; waiting to see whether investigators will learn anything truly significant from Andrew Miller, a matter that is currently before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit; and resolving the mystery grand-jury case, which pertains to some foreign-government-owned institution. In this iteration of “wrapping up,” the team largely knows where it is heading, and it’s just a question of getting there. Think of James Comey’s comments about the Hillary Clinton email investigation; by the time the FBI sat down to interview her, he has said, it was quite clear there wouldn’t be a case unless she lied. But the interview had to happen anyway. The FBI was wrapping up.

The problem is that this explanation doesn’t answer the question of how significant those loose ends are to the investigation or how long they will take to tie off—putting aside the fact that it is now mid-February and the investigation still shows no signs of ending. The famed biographer Robert Caro has been wrapping up the fifth volume of his five-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson—the first volume of which was published in 1982—for years. The scope of work is known. He presumably knows what he’s going to say. And yet, as Caro has said, he is “still—at the age of 83—several years from finishing it.” Countless Game of Thrones fans have been waiting since 2011 for George R. R. Martin to wrap up The Winds of Winter, the next volume in his “Song of Fire and Ice” series.

There’s another plausible way to understand Mueller’s “wrap-up” phase. It could mean that the investigative phase of the probe is nearly complete—with or without significant loose ends—but that major decisions are still to come. In other words, if the Mueller team has all or almost all the information it needs, it may still have to decide exactly what to do with that information. Will there be more indictments when the investigation “wraps up,” or will prosecutors ride off into the sunset, leaving a report on Bill Barr’s doorstep?

To say that the investigation is done, in other words, doesn’t answer the question of investigative outcome. If you’re one of those people who have invested a great deal in the Mueller investigation, you might—quite plausibly—see in this decision point the great cataclysm, the moment in which Mueller reveals all in a set of climactic charges. Conversely, if you’re one of those people who think the premise is wildly overstated and the whole thing is a “witch hunt,” you’re waiting for the emperor to be revealed as naked. But the point either way in this iteration is that “wrapping up” is not necessarily the end; it’s merely the end of the investigation.

[Joshua Zoffer and Niall Ferguson: Mueller and a blue House could bring down Trump]

There’s a third possible explanation: Perhaps both the investigative and prosecutorial decision-making dimensions of the probe are nearly complete, and “wrapping up” means that the special counsel’s office is in the process of drafting a report. In this version, there will be no more indictment fireworks, no more Friday news surprises—or perhaps just a few more. The wrap-up is the writing of some kind of accounting.

But again, that leaves the question of what that accounting will say. It’s rather different if it contains explosive allegations of presidential misconduct that the prosecutor contends would be indictable if committed by someone other than the president than if Mueller slinks off into history with a report that simply says he found insufficient evidence of any crime to bring a case. Assuming this third explanation is accurate, we also don’t know what form such a report would take or how much the public or Congress would see of it. Will it be made public, as congressional Democrats have advocated? Will Congress even be sent the unredacted version of the report? Or will Mueller submit a document directly to Congress, as Watergate Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski did with his Road Map? So to say that Mueller is wrapping up in this sense says very little about the outcome of his work.

But consider a final possibility: All three of these processes could be taking place simultaneously. Mueller could be on an investigative downslope that will take a bit more time; he will then have decisions to make; and he is in the meantime completing his report.

To sum up, we don’t know how long Mueller will be working; we don’t know whether or how many indictments are left to come, or for what; we don’t know what any report will say; and we don’t know when any of this will happen.

It’s a good thing we know that Mueller is wrapping up.

As the Grammys dragged into its fourth hour on Sunday night, the storied producer Jimmy Jam told the audience that it was time to pay tribute to yet another titan of music. Dolly Parton had already presided over her own medley and Diana Ross had thrown herself a birthday bash; Aretha Franklin’s memorial was still to come. The recipient of the next fete, rather, would be Neil Portnow, the bespectacled, white-bearded 71-year-old who has routinely bored Grammys audiences since he became the Recording Academy’s president in 2002.

It’s Portnow’s last year in his run as the longest-acting chief in Grammys history. So after a montage about the Recording Academy’s good works—museums, charities, concerts, opportunities for Portnow to pose with Barbra Streisand—another montage had musicians rave about Portnow’s tenure. Celine Dion bid bon voyage. Chick Corea said, “You’ve helped us keep the music fires burning bright” and played a piano riff. Then it was Portnow’s turn to talk, which he did for longer than any musician’s acceptance speech.

It was a lot of time devoted to a bureaucrat, and Slate, helpfully, has put together a gallery of more Portnow content for the precisely zero people who were left asking for it. This was not just any insider indulgence though; it was an attempt to polish a damaged image. More and more, when it comes to the well-publicized flaws of the Grammys—and really, of gatekeeping institutions of all sorts—public scrutiny is turning toward the behind-the-scenes types who’ve called the shots for extreme lengths of time.

Portnow found himself in pop-culture controversy in 2016, when Kanye West requested a meeting about making the Grammys more “relevant,” which is partly to say, more inclusive of hip-hop, a genre that hasn’t won an Album of the Year award since 2004. Portnow said he was game to collaborate, but he also gave interviews in which he made statements such as, “No, I don’t think there’s a race problem at all” with the Grammys. West hasn’t attended the ceremony since then, and not until 2019—the first show after long-overdue expansions were made to the Academy’s voting body—did a rapper (Childish Gambino) win Song of the Year or Record of the Year.

But Portnow only became a true celebrity bête noire when, after the 2018 Grammys telecast gave out just one trophy to a female artist, he said women needed to “step up” in the music industry. Rebuking female artists and execs who’d long spoken about the structural obstacles facing them, the comment displayed breathtaking ignorance or insensitivity from someone with so much ostensible power in the industry. The ensuing backlash was fierce. Sheryl Crow and Pink tweeted complaints. Fiona Apple played a concert in a Kneel, Portnow tee. Vanessa Carlton campaigned for him to step down. Portnow apologized quickly, and after another scandal—accusations that the Grammys show siphoned money away from charity—announced that he would retire soon.

The brouhaha wasn’t forgotten Sunday so much as loudly atoned for. There was lots of celebrating women in music from the host, Alicia Keys, who started the show by summoning the team of Michelle Obama, Lady Gaga, Jada Pinkett Smith, and Jennifer Lopez. The female artists Kacey Musgraves, Cardi B, H.E.R., and Dua Lipa took televised prizes, though the latter did so with a dig at Portnow’s “step up” rhetoric. Then there was Portnow’s speech, which advocated inclusivity in parodically mealymouthed fashion. An actual quote that is not from a seventh grader’s civics essay: “The need for social change has been a hallmark of the American experience from the founding of our country to the complex times we live in today.”

The reaction shots from women in the audience during Portnow’s speech didn’t exactly radiate approval. The length and dreariness of his talk, in fact, asked frustrating questions of the viewer. Who wanted this combined display of contrition and self-celebration from Portnow? What could he say to cover up the fact that he had run the Recording Academy for more than 15 years and was still able to suggest in 2018, at the height of the #MeToo wave, that women are just not trying hard enough? How much denial did he have to be in about the resentment facing the Academy to say, “Please know that my commitment to all the good that we do will carry on as we turn the page on the next chapter of the storied history of this phenomenal institution”?

The Grammys—ever tepidly reviewed and rated—is, of course, not just Portnow’s mess. Which is why it was fitting that days before the show, another backstage figure made headlines for unhappy reasons. Ariana Grande had been advertised as a performer at the Grammys, but ended up pulling out. Ken Ehrlich, the telecast’s producer, told the Associated Press that it was just a logistical issue. “When we finally got the point where we thought maybe it would work, she felt it was too late for her to pull something together for sure,” he said.

But Grande, on Twitter, called Ehrlich a liar: “I can pull together a performance over night and you know that, Ken. It was when my creativity & self-expression was stifled by you, that I decided not to attend.” Grande said she’d offered three songs, presumably from her new album, to play at the show—but was encouraged to do something else in the interest of political game-playing and favor trading. It’s a flap that recalls reports from 2018 that Lorde, the only woman nominated for Album of the Year, didn’t play because the Grammys’ producers had only offered collaborative, not solo, performing slots, including in a Tom Petty tribute.

You know that, Ken has quickly become a catchphrase among Grande fans, one that—as with the Portnow controversies—brings new attention to a power player who’s been in plain sight for a very long time. The 76-year-old Ehrlich has been producing the Grammys since 1980, which is more than one and a half the amount of time Grande has been alive. He understandably has pointed to that epic tenure when defending himself. “The thing that probably bothered me more than whatever else she said about me is when she said I’m not collaborative,” Ehrlich told Rolling Stone.

“You can ask Christina Aguilera, who I asked to do ‘It’s a Man’s World’ for James Brown,” he continued. “You can ask Melissa Etheridge, who finished her cancer treatment and I put her out on stage, bald, doing Janis Joplin. You can ask Ricky Martin, who overnight became the creator of the Latin-music revolution. Ask Mary J. Blige, who was scared shitless to go out there and do ‘No More Drama.’ I basically worked with her to mold it.”

That litany indeed includes some of the highlight moments from Erhlich’s reign. Producing an event like the Grammys is an enormous task involving an overwhelming number of elements—personnel, equipment, creative concepts—and that he’s met that challenge for so long is a real feat. But Ehrlich’s 39-year stint has also seen perennial grumbles from viewers about strange performance choices and overlong, tribute-packed, gimmick-obsessed mediocrity, all of which was well on display Sunday night (one top-of-the-head example: J. Lo, of all people, doing the Motown medley).

It’s also seen, in recent years, mounting outcry from not just Grande and Lorde, but also other huge artists such as Frank Ocean and Justin Bieber who for one reason or another have been alienated from what’s supposedly “music’s biggest night.” After Sunday’s show, Nicki Minaj joined their ranks by blasting Ehrlich by name. “I pissed off the same man Ariana just called out for lying,” she tweeted. “Grammy producer KEN. I was bullied into staying quiet for 7 years out of fear.” The full details of their spat would be revealed soon, Minaj promised, building suspense in much the same fashion she has when beefing with rappers. Ehrlich has yet to respond.

Identity-based theories for why two white male Baby Boomers with incredible job security are in this position may be easy to come up with. But whatever the reasons, Ehrlich and Portnow have been very publicly faltering in the crucial superstar-relations department. Take last night’s viral moment when Drake popped up in a rare Grammys appearance to accept the Best Rap Song win. His speech mildly dissed the entire concept of giving awards for art: a classic gripe that he simply put in new terms. But when the show seemed to cut him off to go to commercial, it gave the appearance of producers with thin skin. Later, Grammys sources told The Hollywood Reporter that Drake actually finished his speech and was given a chance to return to stage. That they’re having to make such clarifications at all, though, hints at something amiss in the control room.

Ehrlich has one year left in his production contract, and has said he’s unsure about what comes next. Portnow has given his last Grammys speech, and the Recording Academy has not determined its next president. The latter leaves behind laudable things: legislative victories, philanthropic work, many supporters in the industry, and, as of this year, reforms in voting and awards giving to address widespread criticisms about representation and relevance. But the fact that such critiques were being made so fiercely for so long is explained, surely on some level, by the fact that the people in charge have been so long-serving. With new blood, maybe this show can be saved after all.

Accidents happen during home-improvement projects, even in space.

The mishap unfolded on the International Space Station, which orbits about 250 miles above Earth, circling the planet every hour and a half. Earlier this month, NASA astronauts had gathered in the bathroom to install a pair of stalls for an extra enclosure that would provide some more privacy. As they worked, they twisted off a metal bit that connects a water unit to a hose that astronauts use for toothbrushing, bathing, and other hygiene routines. And that’s when two and a half gallons of water came bursting out.

The crew responded as they would on Earth: They grabbed a bunch of towels and scrambled to mop up the water. They attached a new bit to the unit and completed their work.

The incident was detailed in one of NASA’s daily dispatches that describe events on the ISS. History has treated astronauts as nearly mythical figures, but their day-to-day activities are usually quite tedious. The thought of them frantically trying to stop a leak in the bathroom makes them wonderfully relatable.

[Read: How to brush your teeth on the International Space Station]

But a plumbing accident in space has little in common with one on the ground.

For starters, there’s the feeling of weightlessness. (Technically, astronauts are subject to 90 percent of the gravity that we feel here on Earth, but the station’s brisk traveling speed of 17,500 miles per hour keeps everything on board in a constant free fall that resembles zero gravity.) The ISS is equipped with handrails and footrests so that astronauts can push themselves around the station or stay in one place while they’re working on something. Tools can drift away and out of reach.

So can water. Unleashed in weightlessness, water behaves like soap bubbles blown from a wand. Water molecules are more attracted to one another than molecules of another substance. They like sticking together. On the ISS, that means water molecules pull themselves together into a shape with the least amount of surface area: a sphere. But unlike its soapy counterpart on Earth, this kind of bubble doesn’t pop and vanish.

There is no photographic evidence of the leak, according to a NASA spokesperson. To imagine how it may have transpired, I reached out to Tom Jones, a former NASA astronaut and the author of Ask the Astronaut: A Galaxy of Astonishing Answers to Your Questions on Spaceflight. Jones flew on the Space Shuttle three times before the program ended in 2011. He hasn’t spent any time on the ISS—he helped assemble the station during his last mission in 2001—but he has experienced firsthand the strange phenomena of water in microgravity.

“If it was a slow leak, it would have built up into a big, undulating blob that would have drifted off or crept along the wall with surface tension,” Jones says. “If it was under a higher pressure and it was coming out at a fast rate, it would spray and make droplets go flying across the cabin.”

Jones says the first scenario is preferable. It would be easier to chase after fat globs of water than tiny beads.

Water, like most earthly comforts, is a precious resource on the ISS. The loss of two and a half milk jugs’ worth of water seems concerning. But none of the liquid was actually wasted. The crew left the soaked towels out to dry, and the water eventually evaporated. The systems that control the station’s temperature and humidity sucked up the moisture and dumped it back into a mechanism that produces potable water.

It is thanks to water’s unpredictability in space that there are no faucets or showerheads on the ISS. Astronauts use squirt-gun–like hoses to dispense and carefully distribute water onto washcloths and toothbrushes. Showers are a distant daydream. There’s no toilet flushing, either. Contrary to some news reports about a leaky toilet, the toilet system on the ISS doesn’t use water.

Astronauts urinate into a hose with a special funnel on top. (Don’t worry, everyone gets a personal funnel.) They flip a switch to activate a fan in the tube, and the liquid is suctioned away. For solid waste, astronauts stick their feet into stirrups and sit down on a typical toilet bowl. Urine is recycled in the station’s life-support systems and converted into drinkable water. The rest takes a rather dramatic journey: Solid waste is sealed in plastic bags or metal containers. Astronauts eventually transfer the waste, along with other trash, to departing cargo ships. The ships undock from the station and fall back to Earth, where they burn up in the atmosphere like a meteor shower.

Astronauts upgraded the bathroom area this month as they wait for a brand-new toilet to arrive in 2020. Their current commode is a Russian-designed system that the United States bought from its partner on the ISS for $19 million in 2007. NASA promises that the new toilet, designed by an American company, is “simpler to use” and “provides increased crew comfort and performance.” The agency also wants the model to work in other, future space habitats.

[Read: What should we do about the International Space Station?]

Using the new toilet will likely require some preparation. Astronauts throughout history have received extensive training on the myriad spaceflight systems, the lavatory included. In the Space Shuttle days, astronauts had to practice using the toilet before they launched. The simulator came with a video camera at the bottom of the bowl, pointing up. Astronauts plunked down on the bowl, peered at a television monitor in front of them, and watched themselves, in real time, wiggle around and rehearse the proper placement.

“You had to be serious about it, because if you didn’t get those fundamentals down, then you’re going to make a mess for you and your crewmates up in space,” Jones says.

But it was still awkward. “The constant fear we all joked about was that that screen of your bottom being displayed on the simulator was also being piped over to mission control,” he says.

As far as leaks go, the recent watery fiasco is pretty tame. Last summer, crew members discovered a small hole in the Russian section of the ISS that had leaked air out into space, temporarily causing the air pressure inside the station to drop slightly. The incident drew considerable interest from the public, especially when the head of Russia’s space agency suggested that the hole may have been drilled deliberately, before or after that segment launched to space. NASA dismissed the sabotage rumors. Officials have yet to provide an explanation.

The crew wasn’t in any danger. The Russian cosmonauts patched up the opening soon after it was found, using sealant and gauze on board—just another instance of some DIY in space.

The potential judgment of students can lead a teacher to do strange things. For Monique Mongeon, an arts educator in Toronto, starting a job teaching adults sparked a small crisis of confidence. “I was in my mid-20s, and I was looking at things I could do to make myself feel like a person who had authority to stand in front of a bunch of other 20-somethings,” she says. After ruling out fancy bags and shoes as too extravagant, Mongeon settled on a sleek $45 water bottle. “I was scrolling through websites thinking, Which of these S’well bottles looks like the kind of person I want to be?”

Nine years ago, there was only one S’well, and it was blue. Now you can get the curvy, steel-capped bottles in more than 200 size-and-color combinations, including some that look like marble or teakwood. Many are customizable with your initials. The big ones will hold an entire bottle of wine, and smaller versions are made for cocktails or coffee. Teens offer S’well bottles to propose to prospective prom dates. They’re a common sight in Instagram photos of artfully stuffed vacation carry-ons and aesthetically pleasing desk tableaux.

S’well’s success is impressive, but the brand has a host of competitors nipping at its heels in what has become an enormous market for high-end, reusable beverage containers. If nothing in S’well’s inventory calls out to you, maybe you’ll like a Yeti, Sigg, Hydro Flask, Contigo, or bkr. A limited-edition Soma bottle, created in collaboration with the Louis Vuitton designer Virgil Abloh and Evian (itself a legend of designer water), was recently feted at New York Fashion Week. VitaJuwel bottles, which can cost more than $100, promise to “restructure” your tap water using the power of interchangeable crystal pods.

[Read: The art of woke wellness]

On the surface, water bottles as totems of consumer aspiration sound absurd: If you have access to water, you can drink it out of so many things that already exist in your home. But if you dig a little deeper, you find that these bottles sit at a crossroads of cultural and economic forces that shape Americans’ lives far beyond beverage choices. If you can understand why so many people would spend 50 bucks on a water bottle, you can understand a lot about America in 2019.

The first time I coveted a water bottle was in 2004. When I arrived as a freshman at the University of Georgia, I found that I was somehow the last person alive who didn’t own a Nalgene. The brand’s distinctive, lightweight plastic bottles had long been a cult-favorite camping accessory, but in the mid-2000s, they exploded in popularity beyond just outdoorsmen. A version with the school’s logo on it cost $16 in the bookstore, which was a little steep for me, an unemployed 18-year-old, but I bought one anyway. I wanted to be the kind of person all my new peers apparently were. Plus, it’s hot in Georgia. A nice water bottle seemed like a justifiable extravagance.

Around the same time, I remember noticing the first flares of another trend intimately related to the marketability of water bottles: athleisure. All around me, stylish young women wore colorful Nike running shorts and carried bright plastic Nalgenes to class. “With Millennials, fitness and health are themselves signals,” says Tülin Erdem, a marketing professor at NYU. “They drink more water and carry it with them, so it’s an item that becomes part of them and their self-expression.”

[Read: Everything you wear is athleisure]

Now, across Instagram, you can find high-end water bottles lurking around the edges of stylized gym photos posted by exercisers and fitness instructors. Usually these people aren’t being rewarded for the placement with anything but likes. Sarah Kauss, S’well’s founder and CEO, says people have been photographing her water bottles since the company began in 2010. “I’d receive hundreds of pictures a week from customers,” she says. “I wasn’t giving them anything for it. There wasn’t a free bottle or a coupon code or anything other than customers just wanting to show their own experience.”

Kauss says she always knew the bottle’s appearance would be important, even though positioning something as simple as a water bottle as a luxury product was a bit of a gamble. “As I moved up in my career, I was upgrading my wardrobe, and the bottle that looked like a camping accessory really didn’t serve my purpose anymore,” she says. When she noticed fashionable New Yorkers were carrying luxe disposable plastic bottles from brands such as Evian and Fiji, she realized reusable bottles could use a makeover, too.

Kauss and her contemporaries struck at the right time. The importance of fitness and wellness were starting to gain a foothold in fashionable crowds, and concerns over consumer waste and plastic’s potential to leach chemicals into food and water were gaining wider attention. People wanted cute workout gear, and they wanted to drink water out of materials other than plastic. Researchers have found that the chance to be conspicuously sustainability-conscious motivates consumers, especially when the product being purchased costs more than its less-green counterparts.

Nearly a decade on, the water-bottle trend shows no signs of slowing, and people just seem to like their fancy bottles a lot. The insulated metal variety, the most popular, does a far better job than plastic of keeping beverages at ideal temperatures. They’re durable and useful. When I put out a call for opinions on Twitter, I heard from hundreds of people about how much they loved theirs. Rebecca Thomas, a 28-year-old in Atlanta who owns three S’wells, says she once paid a ransom to an Uber driver after she left one behind in the car. (“That’s when I decided I’d never put wine in one again,” she says.) Others were similarly dedicated. “I will be buried with all of my different sizes of Hydro Flask,” says Elizabeth Sile, an editor in New York City. “Maybe by then Hydro Flask will come out with a coffin, so I can be buried in that, too.”