Numa das tardes mais quentes do ano, em uma cafeteria da Asa Norte, em Brasília, Dom Werneck pediu a segunda dose de vodka com muito gelo. Ele é um dos líderes do movimento intervencionista, que quer a volta da ditadura militar no Brasil. Em quase três horas de conversa, ele explicou os motivos que fizeram com que boa parte dos militaristas decidisse apoiar um candidato – Jair Bolsonaro – e depois passasse a conspirar abertamente contra ele.

Em uma incursão a grupos e canais militaristas pela internet, vi que o que ele falava é endossado por outros representantes, e que o grupo intervencionista tem mais poder de fogo do que se supunha quando começou a aparecer, a partir de 2013.

Ele tinha carisma, boa lábia e nenhum pudor em defender o regime militar.

Foi também a partir desse ano que os intervencionistas passaram a ver em Bolsonaro a solução para os seus anseios, uma vez que um golpe militar nos moldes tradicionais, como o de 1964, estava longe de acontecer. A saída seria alçar alguém pelas vias democráticas, e o ex-capitão parecia se encaixar perfeitamente no papel. Ele tinha carisma, boa lábia e nenhum pudor em defender o regime militar.

O agora presidente, inclusive, falava abertamente sobre “acionar o artigo 142″ quando chegasse ao poder. O artigo em questão é sempre evocado por intervencionistas como a prerrogativa constitucional para um golpe militar, ao apontar que caberia às Forças Armadas a garantia da “lei e da ordem” no país.

Werneck tinha isso em mente quando, a partir de 2013, se aproximou do ex-capitão. Ele reivindica a autoria de atos que ajudaram a tornar Bolsonaro conhecido pelo grande público e alega ter sido o autor da ideia de levar militantes para recepcionar o ex-deputado federal no aeroporto de Brasília semanalmente e publicar vídeos de Bolsonaro nos braços do povo – o que se tornou uma das marcas da sua caminhada até o Planalto. Também criou o grupo “Bolsonarianistas” no WhatsApp, que teve mais de 80 subgrupos pelo país – um embrião do que viria a ocorrer na campanha eleitoral.

“Gosto de quebrar estereótipos”, diz Werneck ao comentar que usa barba comprida e camisa jeans “como um comunista”.

Foto: Reprodução/Facebook

Como uma espécie de “assessor informal”, Werneck seguia Bolsonaro pela Câmara dos Deputados, fazendo entrevistas “exclusivas” e transmitindo os discursos do parlamentar em lives em suas páginas – hoje ele tem duas no YouTube, uma com 76 mil assinantes e, a outra, 47 mil; além de 55 mil fãs no Facebook. Em setembro de 2016, ele teria avisado o então deputado sobre uma comissão com Maria do Rosário, pouco após o incidente em que ele disse que “não a estupraria porque ela não merece”. Bolsonaro foi ao local, bateu boca com meio mundo e virou notícia. Werneck registrou ao vivo.

Os intervencionistas se incomodam com a receptividade de Bolsonaro à ideologia liberal e a subserviência a países como EUA e Israel.

A estratégia com as ações era dar visibilidade para o ex-deputado. Até então o ex-capitão reformado era um parlamentar apagado, que nunca relatou projetos relevantes, presidiu comissões ou liderou bancadas, e que somente ganhava a luz dos holofotes por causa das polêmicas em que se envolvia.

Werneck se apresenta em vídeos como um dos organizadores das greves de caminhoneiros, categoria que se aproxima cada vez mais dos intervencionistas. Nos atos, principalmente na paralisação de 2018, não foi raro ver caminhões com faixas pedindo socorro das Forças Armadas e manifestando apoio a Bolsonaro – que chegou a apoiar a greve e depois recuou – como de praxe.

Relação esfriaMesmo agindo como cabo eleitoral, Werneck diz que sempre teve um pé atrás com Bolsonaro. “Todo mundo sabia que ele era um mau militar, e isso pega mal no meio”, afirma. Ele diz que dava “apoio crítico” ao deputado apenas para alçar ao poder uma pessoa minimamente ligada ao militarismo.

Os intervencionistas também se incomodavam com a receptividade de Bolsonaro à ideologia liberal, com a aproximação com o atual ministro da Economia, Paulo Guedes, e a frequente subserviência a outros países, principalmente Estados Unidos e Israel. Essas características, segundo Werneck, demonstravam uma aproximação com o “establishment” e conflitavam com o nacionalismo pregado pelo meio militar. Aos poucos, ficou difícil não enxergar o ex-deputado como um “traidor da causa”.

‘A gente não concorda com nada do que a Maria do Rosário prega, mas pelo menos ela é fiel à sua ideologia.’

“Na época, Bolsonaro tinha um discurso mais nacionalista e reconhecia que no atual modelo republicano seria impossível colocar o Brasil nos trilhos. Depois, ele foi para o lado liberal. Isso me irritou profundamente. Eu e muitos intervencionistas rompemos com ele e voltamos nossos esforços para uma insurgência militar”, afirma Ricardo Dex, intervencionista que fez parte de um dos grupos que costumava recepcionar o ex-deputado no aeroporto de São Paulo.

A falta de coerência no discurso de Bolsonaro é o ponto mais criticado. Nessa lógica, até uma das inimigas do ex-deputado teria mais valor que ele. “A gente não concorda com nada do que a Maria do Rosário prega, mas pelo menos ela é fiel à sua ideologia, e isso a gente respeita”, alfinetou Priscila Azevedo, esposa de Werneck, também youtuber da causa militar.

Werneck era dono de restaurantes, Azevedo trabalhava em um banco privado. Os dois deixaram os empregos há cerca de seis anos. Hoje, pagam as contas com a venda de produtos militaristas e doações dos seguidores.

Foto: Reprodução/Facebook

Ainda durante a campanha eleitoral, diz Werneck, a estratégia mudou: se distanciar de Bolsonaro e transformar seu vice, general Hamilton Mourão, em candidato a presidente. O general acabou se tornando vice na chapa bolsonarista e tudo foi por água abaixo.

Os militaristas se dividiram. Werneck e Azevedo passaram a fazer campanha pelo boicote às eleições e para pressionar a Mourão a dar um golpe. Outros grupos continuaram apoiando Bolsonaro, contando que a presença de Mourão na chapa era decisiva.

Como as eleições aconteceram, a esperança se tornou a de que “algo” eventualmente impedisse o cabeça de chapa de se manter na Presidência, de modo que o vice assumisse. Na visão deles, Bolsonaro estaria sendo usado pelo grupo militar apenas para vencer a eleição, por ter bons resultados nas pesquisas eleitorais. O grupo militar que encabeça o governo, formado pela maior presença de militares no primeiro escalão desde a redemocratização, é quem estaria dando as cartas de verdade.

“Pode ver todas as vezes que o Bolsonaro teve que recuar em tão poucos dias de governo [a nossa conversa ocorre no dia 15 de janeiro]. Ele fala uma coisa e, se o grupo militar não gostar, é obrigado a voltar atrás”, comentou Priscila. Um dos exemplos foi a permissão para os Estados Unidos abrirem uma base militar no país, que foi defendida por Bolsonaro, sofreu grave resistência dos militares do alto escalão e em seguida foi descartada.

“Não vai ter golpe interno. Não precisa. O próprio Bolsonaro vai se destruir”, comentou Werneck. “Ele [Bolsonaro] sabe que as pessoas da Presidência estão usando ele protocolarmente, institucionalmente, para ser o presidente. Ele era o cara que deu arranque, pegou popularidade. Não tinha como colocar outra pessoa pra disputar. Os militares usaram o que tinham. Usaram ele”, disse.

Os intervencionistasApesar de se apresentar como Dom Werneck na internet, seu nome verdadeiro é Reginaldo Florêncio Verneque. Ele é autor de transmissões ao vivo pelo Facebook e YouTube com centenas de milhares de visualizações, em que defende qualquer coisa relacionada às Forças Armadas. Tem barba comprida e usa camisa jeans, “como um comunista”, segundo o próprio. “Gosto de quebrar estereótipos”, disse. Sua esposa, Priscila, nos acompanhava no café. Vestia camiseta verde-oliva com adereços que imitavam insígnias militares.

Agora o “grupo de malucos” intervencionistas tem trânsito na Esplanada. E tem como maior representante o vice Mourão.

Werneck admite que, há até pouco tempo, os intervencionistas eram tratados como um balaio de malucos, em que alguns poucos gatos pingados protestavam nas ruas e basicamente ninguém dava bola. O movimento cresceu nos últimos anos, amparado pelos escândalos de corrupção e o sentimento de ódio à política tradicional. O ponto alto veio em 2015, durante os atos pelo impeachment da ex-presidente Dilma Rousseff, em que até 48% das pessoas disseram apoiar um novo golpe militar, segundo pesquisa da Universidade de Vanderbilt, dos Estados Unidos, em parceria com a Universidade de Brasília e apoio da Capes.

O casal coleciona milhares de seguidores e haters pela causa que defende. Apesar de serem os intervencionistas mais conhecidos, e talvez os mais influentes, também são alvos de acusações de se apropriarem do dinheiro de viúvas de militares que sonham com a intervenção. Werneck era dono de restaurantes, Azevedo trabalhava em um banco privado. Os dois deixaram os empregos há cerca de seis anos. Hoje, pagam as contas com a venda de produtos militaristas e doações dos seguidores.

Agora o “grupo de malucos” intervencionistas tem trânsito na Esplanada. E tem como maior representante o vice-presidente, general Hamilton Mourão.

Em vídeos de outros intervencionistas, é flagrante o incômodo com o escândalo de corrupção que envolve Flávio Bolsonaro.

Mourão já defendeu a intervenção militar para “salvar o país” da corrupção – ele perdeu um cargo no Exército e se aposentou por causa dessas declarações. Durante a campanha eleitoral, no ano passado, despertou comichões prazerosos nos militaristas quando falou da possibilidade de um “autogolpe” do presidente, junto às Forças Armadas, na hipótese de anarquia. Hoje, seu discurso é bem mais moderado. Ainda assim, é visto como herói por militares e simpatizantes. Intervencionistas juram de pé junto que são próximos a ele. Werneck foi o único civil convidado para a cerimônia interna que homenageou o general quando passou à reserva.

Apesar de o movimento ser heterogêneo, as opiniões do casal parecem ter respaldo no universo militarista. Em vídeos de outros intervencionistas, é flagrante o incômodo com relação ao possível escândalo de corrupção que envolve o senador Flávio Bolsonaro, filho de Jair, e o motorista Fabrício Queiroz.

“Essa história do Queiroz está me cheirando cabide de emprego (…) Eu não boto a minha mão no fogo”, disse Plaucio Pucci, um militarista que poucas semanas antes pedia voto para Bolsonaro. “Meu filho, passa logo um antivirus nessa máquina. Caso contrário ela apagará rapidamente”, ameaçou outro, Alexandre Bellei. “Qual é a diferença de um corrupto de R$ 90 milhões e um de R$ 90 mil? (…) Agora fica esse nhenhenhé. Não tem nhenhenhé, é corrupto igual”, afirmou mais um youtuber, José Márcio.

Após Mourão defender a intervenção militar em uma palestra, Werneck mandou fazer um banner com 10 metros de altura em homenagem ao general.

Após Mourão defender a intervenção militar em uma palestra, Werneck mandou fazer um banner com 10 metros de altura em homenagem ao general.

Quando Mourão apareceu no noticiário nacional, em setembro de 2017, após dizer em uma palestra que poderia haver intervenção militar no caso de o Judiciário “não solucionar o problema político”, Werneck viu a notícia e foi para uma gráfica do Gama, cidade do Distrito Federal onde mora, mandar fazer um banner com 10 metros de altura com uma foto de Mourão e a frase “Obrigado militares por nos salvar. Obrigado General Mourão”. Levou o banner para a frente do Congresso e o içou.

Passou a acompanhar de perto o general e por isso foi chamado para a despedida dele, que registrou em um vídeo de 25 minutos em seu canal. Por causa dessa proximidade, Werneck foi procurado no começo do ano passado por Levy Fidélix, que queria levar o general para a política, filiando-o ao PRTB.

O intervencionista gravou dois vídeos com Fidélix. Em um deles, o presidente do PRTB aparece comicamente vestido com roupas militares em uma loja de produtos militares dizendo que está “pronto para a guerra” e que é “intervencionista de coração”.

Werneck e Priscila são amigos do general Paulo Assis, que foi comandante de Mourão nas Forças Armadas e já contou ao Intercept como o aconselhou a entrar no mundo da política. O casal estava presente no dia em que o general assinou sua filiação ao partido. Os dois também se filiaram. Depois, tomaram um chope gigante para comemorar.

O casal é próximo de Mourão e esteve presente no dia em que o general assinou sua filiação ao PRTB.

Foto: Reprodução/Facebook

Werneck reclama que Fidélix usou Mourão como ferramenta para garantir ao seu partido a continuidade no mundo político, já que não elegeu nenhum parlamentar este ano – nem ele próprio, que concorreu à Câmara – e, por isso, seria impactado pelas limitações da cláusula de barreira, que impede que partidos sem representantes no Congresso tenham acesso a recursos do fundo partidário e tempo de televisão.

Uma frase que Werneck disse me chamou a atenção. Era que Bolsonaro não sabia lidar com a oposição dos intervencionistas, já que eles não podem ser considerados comunistas ou esquerdistas, como costuma atacar seus inimigos políticos. “Somos de direita, somos conservadores. Somos até mais radicais do que os próprios militares, porque nós queremos que se feche Congresso e Supremo e tenha uma junta militar governando o país”, disse.

“É a tal da mão amiga e braço forte. Nós somos a mão amiga. Eles são o braço forte”.

The post Como os intervencionistas criaram o ‘mito’ Bolsonaro e depois pularam do barco appeared first on The Intercept.

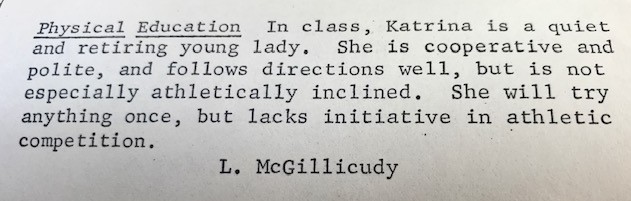

Pressure for Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam to resign is mounting after a medical school yearbook page surfaced showing a photo of a man in blackface, initially understood to be Northam, standing next to a man in Ku Klux Klan robes. Over the weekend, Northam denied being in the photo, but apologized for wearing blackface while impersonating Michael Jackson on another occasion. Reports also revealed that Northam’s Virginia Military Institute yearbook page listed him with the nickname “Coonman.”

Northam has not yet decided whether he’ll resign, but patience among members of his cabinet is wearing thin.

Virginia Education Secretary Atif Qarni posted a statement on the progressive political blog Blue Virginia in which he called his state to reflect on its “ugly history.” He argued that “change is taking too long” and denounced statewide political leadership for its lack of racial and ethnic representation. He went on to express empathy for the disparate treatment that Black Americans face at the hands of police.

“Experiences of several marginalized communities pale in comparison to the Black experience in America,” Qarni wrote. “I have had a few unpleasant experiences with law enforcement; however, I can’t imagine what it must feel like to be slammed to the ground and handcuffed without cause. Or even worse, shot dead.”

The secretary compared anti-black racism to the experiences of him and his wife, Fatima. “My wife wears a hijab and when she and I travel by air, I feel like all eyes are on us; however, I can’t imagine what it must feel like to have your actions be monitored and scrutinized every day of your life, even while running basic errands.”

“I feel anger that my ancestors were colonized by white people; however, I can’t imagine living in a country where my ancestors were trafficked, shackled, beaten, raped, lynched, and enslaved,” Qarni’s statement continues. “White and other people of color can empathize and try to relate to the Black experience in our nation; however, no one can truly grasp the depth of the pain, trauma, humiliation and anguish felt by Black Americans over the last 400 years in this country.”

The governor called an all-staff meeting Monday morning, but made no decision on how to respond to an increasing number of requests from state and national political leaders for him to step down.

In an email to The Intercept, state Finance Secretary Aubrey Layne said that while he serves “at the pleasure of the Governor, I work for the people of Virginia. I just plan to keep doing my job.” Other members of Northam’s cabinet did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Former Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe; Virginia Sens. Tim Kaine and Mark Warner; Rep. Bobby Scott; House Speaker Nancy Pelosi; Congressional Black Caucus Chair Karen Bass; former Attorney General Eric Holder; and former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton are among Democrats who’ve called for the governor to resign. Democratic presidential hopefuls Sens. Cory Booker, D-N.J.; Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y.; Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.; Kamala Harris, D-Calif.; and San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro have also called for Northam to resign.

Virginia’s Democratic leader in the state Senate defended Northam in an interview with the Washington Post on Friday, saying there is no need to examine “something that occurred 30 years ago.” Sen. Dick Saslaw, who’s facing his first primary challenge as a state senator in June, has a controversial history of questioning whether racial or religious minorities could win in the majority-white, majority-Christian state and of defending the state’s Confederate history. Qarni, in 2015, wrote an op-ed detailing challenges he faced while running as a Muslim candidate for the state House of Delegates, and in a comment on a Facebook post criticizing the op-ed, he named Saslaw as part of the problem.

The post “Change Is Taking Too Long” — Cabinet Member Speaks Out Amid Gov. Ralph Northam’s Blackface Fallout appeared first on The Intercept.

“Uma guia que trabalha na Casa Dom Inácio de Loyola marcou vários dos matadores profissionais de João de Deus, pedindo para me localizarem”, escreveu Sabrina Bittencourt. A mensagem de WhatsApp chegou às 14h50 de sábado. Menos de seis horas depois, a mulher que ajudou a denunciar os estupros cometidos por Prem Baba e João de Deus publicou sua carta de suicídio.

“Sou imparável até o fim dos meus dias”, ela havia postado dois dias antes. A notícia de seu suicídio foi aterradora. E a cobertura da imprensa sobre o caso, revoltante. No domingo, seu suicídio foi anunciado por diversos veículos da imprensa. Na manhã seguinte, a história já era outra. A incerteza sobre o local exato da morte, a falta de provas do suicídio e a ausência de detalhes sobre seu velório fizeram a imprensa dar um passo atrás: teria a ativista realmente tirado a própria vida? Começava ali a caçada pelo corpo de Sabrina Bittencourt.

Uma notícia do jornal O Globo, que destacava as “informações desencontradas” sobre a morte, apresentou a hipótese de que Sabrina teria forjado seu suicídio e assumido uma nova identidade. Já textos da revista Carta Capital e do Hypeness citavam a opinião de pessoas próximas a ela sobre a possibilidade de uma “morte simbólica”, inventada para que as ameaças contra ela e sua família cessassem.

Trabalhar para provar que essa mulher forjou sua morte para poder continuar viva é colocar sua cabeça de volta numa guilhotina.Nada poderia ser mais irresponsável. Se a morte for real, a falta de respeito da imprensa pela dor dessa família é, para dizer o mínimo, insensível. Se não for, trabalhar para provar que essa mulher forjou sua morte para poder continuar viva é colocar sua cabeça de volta numa guilhotina com a lâmina pronta para despencar.

Como eu, todas as jornalistas que mantinham contato com ela – que costumava nos enviar mensagens diariamente no WhatsApp por uma lista de transmissão – sabiam o quanto ela temia por sua vida. Ainda assim, de alguma forma, a hipótese de ela ter mentido sobre a própria morte parece soar muito mais plausível do que a possibilidade de essa mulher, alvo de ameaças há meses e que havia tocado no assunto naquele mesmo dia, ter sido assassinada.

Print de mensagens enviadas por Sabrina Bittencourt a jornalistas horas antes de publicar uma carta de suicídio no Facebook.

Imagem: Reprodução/WhatsApp

A notícia da morte de Sabrina veio cerca de três semanas depois de conversarmos por uma chamada de vídeo. Nunca tinha visto ou ouvido uma pessoa tão exausta. Isolada em algum canto do mundo, ela contava, abatida, as denúncias que vinha recebendo; sua dedicação em tempo integral ao acolhimento das vítimas; as ameaças incessantes contra ela e sua família; e a mudança constante para evitar ser localizada por quem a ameaçava.

Seu suicídio não deixa de ser uma espécie de assassinato. Os responsáveis são aqueles que ameaçavam matá-la.Nessas condições, seu suicídio não deixa de ser uma espécie de assassinato. Os responsáveis são aqueles que ameaçavam matá-la. Conseguiram. Mas, ao embarcar na hipótese de uma morte forjada sem que isso represente qualquer benefício para a sociedade, a imprensa constrói não apenas um crime sem autores, mas também, como me disse um amigo, um crime sem vítimas.

Em vídeo de 13 de dezembro de 2018, Sabrina desmente notícia de que teria cometido suicídio na época e diz que está “no seu limite” e não irá tolerar “jornalista urubu”.

Qual é o propósito? Qual é a finalidade de ligar para consulados, embaixadas e importunar o único familiar de Sabrina a ter se pronunciado sobre o caso – um menino de 16 anos – sabendo que arriscar a vida de Sabrina (se ela ainda tiver uma) é o único resultado possível da busca por seu corpo?

Esse jornalismo que lava as mãos de suas consequências, cegado pela busca utópica de uma (inexistente) objetividade inabalável, não me interessa. É irresponsável e umbiguista. Seus defensores podem dizer: “É nosso trabalho ir atrás dos fatos, sejam eles quais forem, e reportá-los ao público”. Eu rebato: mesmo quando o único impacto possível de seu trabalho for facilitar o assassinato de uma mulher?

The post A caçada ao corpo de Sabrina Bittencourt appeared first on The Intercept.

House Republican lawmakers are being encouraged by their party’s leadership to play up gruesome murders, rapes, and other crimes committed by undocumented immigrants in the United States.

In a newsletter sent on Friday, House Republican Conference Chair Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., provided the caucus and staff with a messaging update that compiled immigrant crimes by date and congressional district. The newsletter is used by the GOP caucus to provide talking points and messaging guidance. The edition of the newsletter dealing with immigrant crimes, which was obtained by The Intercept, offered a messaging opportunity to leverage the government shutdown against House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.

“Speaker Pelosi made one thing clear during the government shutdown: she doesn’t care about the tragic consequences of illegal immigration on American families,” the newsletter says.

Under the header “The Democrats’ far-left immigration agenda has tragic real-world consequences,” the newsletter goes on to list crimes committed over the last two decades.

The list includes alleged crimes and points out which Republican House members’ districts the events took place in. In one case, “an illegal immigrant from El Salvador was charged with murdering four people” in Rep. Mark Amodei’s Nevada district, the newsletter says. In another, it recounts “the story of a 16-year-old, who was killed in 2000 by an illegal immigrant in a car crash on Father’s Day” in Rep. Barry Loudermilk’s Georgia district. Yet another bullet point describes “an illegal immigrant who previously had been deported in 2015 for a felony drug trafficking conviction [who] was charged with first degree rape” in Rep. Gary Palmer’s Alabama district.

The congressional document mirrors recent tweets by President Donald Trump linking crimes committed by immigrants to the need to expand the wall along the U.S. southern border with Mexico.

Just before the midterm election last year, Trump tweeted a 53-second video featuring Luis Bracamontes boasting about murdering two sheriff’s deputies in 2014. After the clip of Bracamontes, the video flashes text that claims, “Democrats let him into our country … Democrats let him stay.” As independent fact-checkers noted, the message was highly misleading. Bracamontes was deported under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

The House Republican Conference messaging document includes several stories that were simply shared by Republican lawmakers without any names or news stories attached. The House Republican Conference spokesperson declined to comment on the newsletter.

Studies have consistently shown that crime rates are actually lower among foreign immigrants than among native-born Americans. But the strategy does not appear to be a fair-minded discussion of immigration policy — or crime, for that matter.

Across the world, demagogues have deftly exploited bigotry to whip up anger using incidents of murder and rape. Increasingly, social media has become an effective way to weaponize tragic acts and use them for partisan political goals. In Germany, the far-right Alternative for Germany party has singularly focused on several cases of murders committed by refugees to intensify hatred of Middle Eastern immigrants. In Myanmar, lurid stories posted on Facebook detailing purported acts of rape and murder by the Muslim Rohingya minority against the Buddhist majority were used to justify a brutal ethnic cleaning in the northwest Rakhine State. In some cases, the stories were false. Viral stories that focus on the identity of killers to stoke ethnic tension can also be found in India, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, and beyond.

In the U.S., there is a long history of racist violence following politicians’ focus on crimes — real or imagined — by particular minority groups. Across the ideological spectrum, many on social media continue to fixate on the racial or ethnic identity of criminals. Trump’s embrace of the strategy now appears to have reverberated across the Republican Party, with GOP lawmakers now openly encouraged to stoke fear over immigrant crime.

The post GOP Leadership Instructs Lawmakers to Play Up Gruesome Murders and Rapes by Immigrants appeared first on The Intercept.

The Supreme Court will decide this week whether to intervene in a case that could lead to the closure of all but one abortion clinic in Louisiana, potentially leaving tens of thousands of women without meaningful access to care. It is the first of more than a dozen abortion-related cases that are moving through the system and toward the high court. Unless the court takes action, two of Louisiana’s three remaining clinics would likely shutter operations.

At issue is a state law passed in 2014 that requires abortion doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the abortion clinics where they practice. It is identical to a law passed a year earlier in Texas — a law that was stuck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the 2016 decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt.

The admitting privileges law is what is known as a targeted restriction on abortion providers, or TRAP law. Theoretically, it is designed to ensure a continuum of care in the exceedingly rare event that serious complications arise from an abortion procedure. The problem, however, is that it can be nearly impossible for abortionists to obtain admitting privileges — for example, some hospitals require a certain number of admissions as a requisite for granting privileges, but because abortion is so safe, doctors are unable to meet that threshold. (Serious complications requiring hospitalization occur in just .05 percent of first-trimester abortions.) The requirements for obtaining admitting privileges vary from hospital to hospital and can be decided based on politics alone. In Louisiana, two doctors were denied privileges precisely because they provide abortion care, according to court documents filed by the Center for Reproductive Rights, which is challenging the state law.

In Texas, the admitting privileges law in part led to the closure of roughly half of the state’s clinics. CRR challenged that law, and in 2016 the Supreme Court ruled that it could not stand. While the alleged purpose of the regulation was to protect the health and safety of women seeking care, the law did not do that. The court ruled that in order to survive a legal challenge, the actual medical benefit of such a restriction must outweigh the burden it places on abortion access.

While both the Texas and Louisiana laws were making their way through the legal system, a federal district judge in Louisiana blocked that state’s law in a meticulous 112-page ruling. “Without an injunction, Louisiana women will suffer significantly reduced access to constitutionally protected abortion services, which will likely have serious health consequences,” Judge John W. deGravelles concluded in January 2016, roughly five months before the Supreme Court would rule in the Texas case. “The substantial injury threatened by enforcement of the Act — namely irreparable harm to women and the violation of their constitutional rights — clearly outweighs the impact of an injunction” on the state.

Louisiana appealed the ruling to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, the intermediate court that handles appeals coming out of Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana — the same court that ultimately concluded that Texas’s restriction passed legal muster before being slapped down by the Supreme Court. The Texas law, the high court ruled in the Whole Woman’s Health case, “provides few, if any, health benefits for women, poses a substantial obstacle to women seeking abortions, and constitutes an ‘undue burden’ on their constitutional right to do so.”

Theoretically at least, that should have signaled the fate of the Louisiana law. Instead, in a confounding opinion, the majority of a three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit in late September 2018 upheld the Louisiana law. In invalidating the measure, the district court had “overlooked that the facts in the instant case are remarkably different from those that occasioned the invalidation of the Texas statute,” the 5th Circuit Court wrote, and placed the blame for whatever clinics might close squarely on the abortion doctors who the court decided simply had not worked hard enough to secure privileges.

In a strenuous dissent, Senior Circuit Judge Patrick Higginbotham called out his colleagues, writing that the “divergence between the findings of the district court and the majority is striking — a dissonance in findings of fact inexplicable to these eyes.” The ruling, he wrote “ought not stand.” The Center for Reproductive Rights asked the full court to reconsider the panel’s decision, but on a 9-6 vote, the court declined. All four of President Donald Trump’s appointees to the 5th Circuit voted against rehearing the case.

On January 25, CRR took its case to the Supreme Court, asking it to intervene and reverse the appellate court decision. Without action from the court, the law would have taken effect on February 4, leaving a single clinic and doctor left in the state to provide care for the roughly 10,000 women who annually seek abortion in the state, a clearly impossible situation. There are nearly 1 million women of reproductive age in the state.

Late on Friday, February 1, Justice Samuel Alito filed a brief order, staying the case until February 7 to allow the court time to review the court filings. The order, he wrote, does not reflect “any view” on the merits of the case.

The case is the first of nearly 30 involving reproductive rights that are making their way through the court system and will likely signal what direction the new court — now with two Trump appointees — will take in deciding challenges to women’s reproductive autonomy. Indeed, Trump long ago promised that he would appoint only “pro-life” judges to the bench who would be willing to overturn the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade case that legalized abortion nationwide. While the Louisiana case is unlikely to upset Roe, it could reveal the court’s willingness to chip away at the right to abortion by upholding medically unnecessary restrictions that have been passed by dozens of states across the country.

In a stinging op-ed published last week in the New York Times, Nancy Northup, head of the Center for Reproductive Rights, called out the 5th Circuit for going “rogue,” and warned of dire consequences if the high court fails to follow precedent and allows the Louisiana law to stand. “Anti-abortion politicians are hoping that the Supreme Court will stand by and let them legislate abortion out of reach — without the court ever having to reverse Roe v. Wade and related cases assuring access to abortion. That would be death to Roe by a thousand cuts,” she wrote. “The rule of law is on the line, and so is the ability of women in Louisiana and beyond to make their own health decisions and control their own fate.”

The post Louisiana Tests the New Supreme Court on Abortion appeared first on The Intercept.

Less than a month after Democrats — many of them running on “Medicare for All” — won back control of the House of Representatives in November, the top health policy aide to then-prospective House Speaker Nancy Pelosi met with Blue Cross Blue Shield executives and assured them that party leadership had strong reservations about single-payer health care and was more focused on lowering drug prices, according to sources familiar with the meeting.

Pelosi adviser Wendell Primus detailed five objections to Medicare for All and said that Democrats would be allies to the insurance industry in the fight against single-payer health care. Primus pitched the insurers on supporting Democrats on efforts to shrink drug prices, specifically by backing a number of measures that the pharmaceutical lobby is opposing.

Primus, in a slide presentation obtained by The Intercept, criticized single payer on the basis of cost (“Monies are needed for other priorities”), opposition (“Stakeholders are against; Creates winners and losers”), and “implementation challenges.” We have recreated the slides for source protection purposes.

Slide: Recreated by The Intercept

Democrats, Primus said, are united around the concept of universal coverage, but see strengthening the Affordable Care Act as the means to that end. He made his presentation to the Blue Cross executives on December 4. “We don’t discuss private meetings, if there was such a meeting,” said a BCBS spokesperson. Primus said that he did not discuss any kind of deal with the insurers. Henry Connelly, a spokesperson for Pelosi, said that the assessment of single payer was not related to any dealmaking with the industry. “We’re not going to barter lower prescription drug costs for inaction in the rest of the health care industry. The presentation was a broad look at the health care environment and some of House Democrats’ legislative priorities over the next two years in a period of GOP control of the Senate and White House,” Connelly said.

The debate over Medicare for All is playing out on a number of different levels, with no clear consensus over how the government-run, single-payer health plan ought to take shape. Presidential candidates are arguing over whose plan is stronger and gets to full Medicare for All faster, with a debate raging over whether private insurance should be banned outright or operate in addition to universal Medicare coverage.

In the House, even as the idea has picked up momentum with voters and members of the Democratic caucus, Democratic leadership has remained deeply skeptical. Pelosi’s consistent messaging, instead, has been around protecting the Affordable Care Act and lowering prescription drug prices.

“Speaker Pelosi has ensured that Medicare for All will have hearings in the House and tapped Congressman Brian Higgins to take the lead on Medicare buy-in legislation. For the first time, House committees will be seriously examining and tackling some of the questions and possible solutions raised by Medicare for All legislation,” said Connelly.

“The biggest obstacles facing Medicare for All right now are Mitch McConnell and Donald Trump,” he added. “But in the near term, there is a window for Democrats to press Trump to help pass aggressive legislation to negotiate down the skyrocketing price of prescription drugs.”

Primus concluded his presentation with a bullet point that summarized Pelosi’s mission on health care: “Lower your health care costs and prescription drug prices.”

Slide: Recreated by The Intercept

The “your” refers to insurers, who bear costs for medical expenses covered under their plans. That puts insurers and Pelosi, at least in one sense, in alignment, as both have an interest in lower costs. Indeed, insurers regularly negotiate to lower their health care costs, but in practice their efforts have had little effect on the general trend in costs. Drug company patents give pharmaceutical giants outsized power to set prices, and hospital consolidation has also given providers more power in those negotiations. Even where insurers have been able to negotiate lower prices for their own customers, that has done little to shrink the list price of drugs for the public.

At the briefing, Primus mentioned three avenues that Pelosi, a California Democrat, sees toward lower drug prices, sources said. The first, the CREATES Act, is bipartisan legislation, strongly opposed by Big Pharma, that would make it easier for generic drug companies to get access to a sufficient quantity of medications needed to produce generics.

The second measure addresses what’s known as “pay for delay,” in which a drug company pays a generic manufacturer to not produce a generic version of an expensive drug. Democratic leadership wants to ban that practice. The third revolves around the issue of “evergreening,” which is a pharmaceutical industry practice of extending patent protection for a particular drug through a variety of practices. Democrats want to restrict evergreening to encourage cheaper generics make it to the market faster.

Primus’s approach has a strong political logic to it, as taking on every health care stakeholder at once is arguably more difficult than singling out one industry and hammering away, even if the effort is out of step with where progressive energy is at the moment.

Primus is known in Congress as one of the staunchest foes of Big Pharma, while Pelosi’s posture toward Medicare for All is more complicated. Publicly, she has long said that she supports it aspirationally. “I was carrying around single-payer signs probably before you were born, so I, you know, I understand that aspiration,” she said in 2017 during an interview with TV host Joy Reid.

“This is an idea that if we had a tabula rasa, if we were just starting clean, would be the most cost-effective way to go forward. We don’t have that,” she said. “Over 120 or 150 million people in our country have employer-based access to their health coverage and insurance.”

At the time, her objection to Medicare for All was that it distracted from the fight to defend the ACA, which Republicans were trying to gut. “So right now, I’m going to be crude. Now we’re in my living room, so I can be crude. It isn’t helpful to tinkle all over the ACA right now,” Pelosi said. “Right now, we need to support the Affordable Care Act and defeat what the Republicans are doing.”

At other moments, she has said that single payer isn’t popular, arguing, also in 2017, that “the comfort level with a broader base of the American people is not there yet.”

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which operates under Pelosi, in 2017 presented House Democrats with survey data, claiming that it showed that single-payer was a political loser, and that Democrats should focus their messaging on lowering drug prices and protecting the ACA.

Yet a significant number of Democrats who flipped Republican districts blue in 2018 were publicly supportive of Medicare for All, suggesting that it isn’t necessarily the albatross Pelosi and the DCCC believe it to be. A poll from October found that more than half of Republicans support the concept.

Pelosi’s agreement to hold House hearings on Medicare for All came after pressure from the Congressional Progressive Caucus. Yet the hearings will be held by the Budget Committee, which, unlike the powerful Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce committees, would not have final jurisdiction over Medicare for All in the event of a genuine attempt to pass it.

Primus, like Pelosi, is well-known to be a deficit hawk, and both subscribe to the argument put forward by the late Pete Peterson that the debt and deficit are among the gravest threats facing the country. When Peterson, a billionaire who spent hundreds of millions of dollars to push Washington policymakers toward austerity, died in 2018, Pelosi delivered a floor speech that praised him and his vision effusively, speaking of the man as if he’d dedicated his life to eradicating child malnutrition or curing cancer, rather than as a Wall Street tycoon who spent millions pushing for major cuts to Social Security and Medicare. “Pete was a clarion voice for fiscal responsibility, and a strong moral conscience in Washington,” Pelosi said in her House floor eulogy of Peterson, who, by 2012, had already spent half a billion dollars targeting Social Security, Medicare, and other spending programs.

“Pete’s prophetic voice on the importance of fiscal sustainability brought together generations of policymakers, no matter their political background,” Pelosi said. “His legacy will endure in many ways, but especially through the work of the Peterson Foundation, which continues to focus on solutions to America’s fiscal and economic challenges.”

Slide: Recreated by The Intercept

Two of Primus’s five objections to single payer before the Blue Cross audience related to such alleged fiscal challenges. That argument, though, runs headlong into a surge of new interest among Democrats in Modern Monetary Theory, the idea that policymakers are still constrained by a mindset that was justifiable when the U.S. was on the gold standard, but is no longer defensible. Now that the U.S. issues a currency independent of its gold reserves, the obstacle to government spending is inflation, not the debt or deficit, proponents of MMT say. “This zero-sum mentality has no place in a post-Bretton Woods world,” said economist Stephanie Kelton in reaction to Primus’s argument that spending on Medicare for All would foreclose other priorities. (Post-Bretton refers to the global agreement that the dollar will be the global economy’s reserve currency, ultimately decoupled from gold.)

“The U.S. dollar is no longer tethered to gold, which means the federal government is not constrained in its spending by the need to raise revenue. The federal government cannot run out of dollars. This should be painfully obvious, but the gold-standard mentality continues to grip many lawmakers,” Kelton said.

As long as inflation remains low, the government can continue to authorize additional spending. That’s not so much an argument as it is simply an observation of the post-gold-standard reality that austerity advocates like Peterson have spent billions to distort. “The government can afford any new program it chooses to fund. The limits are in the real economy — if producers can’t keep up with the additional demand, inflation will result,” said Kelton, a former adviser to the Senate Budget Committee when it was chaired by Sen. Bernie Sanders. “The federal government — as the issuer of the U.S. dollar — can create all the money that is needed to guarantee health care for all of its people. It’s the rest of us — who merely use the dollar — who have to worry about costs and where to come up with the money to pay a huge medical bill when our private insurer refuses to cover the cost of care.”

This reality has been recognized by former Federal Reserve Chairs Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, as well. “The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So, there is zero probability of default,” Greenspan once said.

Ryan Grim is the author of the forthcoming book “We’ve Got People: The End of Big Money and the Rise of a Movement.” Sign up here to get an email when it’s released.

The post Top Nancy Pelosi Aide Privately Tells Insurance Executives Not to Worry About Democrats Pushing “Medicare for All” appeared first on The Intercept.

President Trump embraced contradiction in his second State of the Union address Tuesday night, offering a rhetorical olive branch to his political opponents while also standing strong on some of his most controversial policies.

In a long and sometimes strange speech—punctuated by a spontaneous outbreak of song and occasional chants of “USA!”—Trump acknowledged the newly claimed Democratic control of the U.S. House and called for “cooperation, compromise, and the common good.” Yet the president also gave no indication he would compromise on his demand for billions of dollars for a wall on the Mexican border; delivered a strong riposte to Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who has called that project “immoral”; and lashed out at investigations into his administration, claiming they imperil American prosperity. The result was a speech that exalted bipartisanship without displaying a strategy, or even an appetite, for achieving it.

The tension in the president’s message was made clear early in his remarks. “The agenda I will lay out this evening is not a Republican agenda or a Democrat agenda—it is the agenda of the American people,” he said, reaching out yet unable to resist the snide habit of refusing to call the Democratic Party by its name.

[Read: The state of the president]

Trump’s implicit response to both House Democratic investigations into his administration and Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s probe was one of the more striking moments of the night. In last year’s speech, he avoided any mention of the Mueller inquiry.

“An economic miracle is taking place in the United States—and the only thing that can stop it are foolish wars, politics, or ridiculous partisan investigations,” Trump said. “If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation. It just doesn't work that way!”

That remark echoes Trump’s habit of labeling the investigations a “witch hunt” in other forums, but doing so in the State of the Union is an acknowledgement that they pose an existential threat to his presidency. If Trump hoped to convince listeners that his own fate and that of the nation are inextricable, it did not seem to work. The line fell flat in the House chamber.

As is often the case, Trump seemed most comfortable and expansive when discussing immigration. He has recently failed to gain much purchase on the issue. Despite embarking on the longest government shutdown in history, he was unable to break Democratic will or convince voters he was making the right call. Instead, Pelosi stared him down and eventually forced him to concede on a short-term funding measure. With funding set to expire again on February 15, Trump on Tuesday tried once more to gain the upper hand, playing on Pelosi’s labeling of the wall as “immoral” without mentioning her name.

“This is a moral issue,” Trump said. “The lawless state of our southern border is a threat to the safety, security, and financial well‑being of all Americans. We have a moral duty to create an immigration system that protects the lives and jobs of our citizens. This includes our obligation to the millions of immigrants living here today, who followed the rules and respected our laws.”

Noting that both parties have voted for some form of border barrier in the past, he insisted that the U.S. must build “a smart, strategic, see-through steel barrier—not just a simple concrete wall.”

Yet the president also seemed to stumble into what would be a major policy announcement. While his administration has worked to limit not just illegal but also legal immigration, Trump said Tuesday, “Legal immigrants enrich our nation and strengthen our society in countless ways. I want people to come into our country in the largest numbers ever, but they have to come in legally.” That diverged from his prepared remarks, which said only, “I want people to come into our country, but they have to come in legally.”

Turning to foreign policy, Trump announced plans to hold a second round of meetings with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un in Vietnam on February 27 and 28. But he punctuated that point with a strange, unverifiable, and self-aggrandizing claim: “If I had not been elected president of the United States, we would right now, in my opinion, be in a major war with North Korea.”

He noted the recent American recognition of Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate leader, but used the moment largely as a bludgeon against the newly resurgent American left. “We are born free, and we will stay free. Tonight, we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country.” Although his plans to withdraw American troops from Syria and Afghanistan have raised hackles among many members of Congress, especially in the GOP, he won bipartisan applause when he said, “Great nations do not fight endless wars.”

As expected, Trump also boasted at length about positive economic indicators, including strong job growth. But he was unable to resist the temptation to exaggerate and dissemble, saying the U.S. had the hottest economy in the world (it doesn’t) and that his administration has cut more regulations than any in history (it hasn’t).

The two most striking takeaways from the speech weren’t things that Trump said. One came when the president recognized Judah Samet, a Holocaust survivor who also survived the massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in October. After Trump noted that Tuesday was Samet’s 81st birthday, the chamber broke into an impromptu rendition of “Happy Birthday.”

The second was a visual: the sight of the women of the House Democratic caucus, sitting together in a bloc and clad in white, both a nod to the women’s suffrage movement and a statement of the new political power of women in the party. Many of these lawmakers were elected in November and ran strongly against Trump. For the most part, they sat, often stone-faced, as Trump spoke—yet at one point, they did jubilantly cheer.

“No one has benefited more from our thriving economy than women, who have filled 58 percent of the new jobs created in the last year. All Americans can be proud that we have more women in the workforce than ever before,” Trump said. A few of the women rose to applaud.

The president spotted them and quipped, “You weren’t supposed to do that,” then added with a grin, “Don’t sit yet, you’re going to like this.” The next line—“And exactly one century after the Congress passed the constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote, we also have more women serving in the Congress than at any time before”—had the bloc of women in white on their feet chanting “USA,” an unexpected moment of bipartisanship.

But that warm and fuzzy moment was notable because it was an outlier. Though Trump spoke the language of compromise early in the speech, there is no indication that he has the will or a strategy to actually govern that way.

“We must reject the politics of revenge, resistance, and retribution—and embrace the boundless potential of cooperation, compromise, and the common good,” Trump said. “Together, we can break decades of political stalemate. We can bridge old divisions, heal old wounds, build new coalitions, forge new solutions, and unlock the extraordinary promise of America's future. The decision is ours to make.”

[John Dickerson: Trump’s hollow call for unity]

Though he would surely object, this passage sounded strikingly like his predecessor in the Oval Office. Trump sounded even more like Obama when he proclaimed his proposals neither Republican nor Democratic but American, paraphrasing Obama’s famous 2004 line that “there’s not a liberal America and a conservative America; there's the United States of America.”

Both Obama and Trump campaigned promising to change the way Washington worked, and both found the reality of governing much harder, though Obama was able to achieve far more in his first two years. And if Trump struggled to find a way to enact his agenda with unified Republican control of Congress, the next two years will be far more challenging for him. Trump won some of his heartiest applause Tuesday night when he discussed the successful passage of criminal-justice reform, a bipartisan priority. But that bill seems like an anomaly—a rare case, in a polarized nation, where both parties actually agreed on substance.

“Many of us have campaigned on the same core promises to defend American jobs and demand fair trade for American workers to rebuild and revitalize our nation's infrastructure, to reduce the price of health care and prescription drugs, to create an immigration system that is safe, lawful, modern, and secure, and to pursue a foreign policy that puts America's interests first,” Trump said. “There is a new opportunity in American politics if only we have the courage, together, to seize it.”

The president is right that members of both parties share some of the same goals. But they have real and deep disagreements about the best ways to achieve them, and even about what success looks like. The problem is not a lack of courage, and if Trump realizes that and has a plan to overcome it, he offered no hint in his speech.

In the midst of a lengthy and mostly familiar discussion of the lawless state of America’s southern border during Tuesday night’s State of the Union address, Trump said, rather unexpectedly, “I want people to come into our country in the largest numbers ever, but they have to come in legally.” It’s a line that immediately attracted the ire of restrictionists, many of whom noted that the “in the largest numbers ever” part was not in Trump’s prepared remarks. Given his propensity towards hyperbole, this could be dismissed as little more than a rhetorical flourish. One wonders, though, if it’s a sign of things to come.

For one thing, it’s in keeping with Trump’s apparent openness to high-skill admissions, as evidenced by his stated desire to revamp the H-1B visa program“to encourage talented and highly skilled people to pursue career options in the U.S.” Embracing high-skill immigration could give Trump something to talk about other than his polarizing border wall.

And the president could use a dose of immigration centrism. Trump’s fixation on a border wall has done little to boost his political fortunes, let alone the restrictionist cause. There is considerable evidencethat his vocal opposition to immigration has made voters more inclined to support it rather than less, and though this effect is most pronounced among Democrats, as one might expect, Republicans haven’t been entirely immune. The net effect of Trump’s rise seems to be that while a shrinking GOP coalition has embraced restrictionism, the country as a whole is moving firmly in the opposite direction. Though jettisoning the cause of immigration control would be a mistake, railing against immigration per se has proven a dead end.

What could the Trump administration do to change the conversation? The White House has already called for a small tweak to the H-1B visa lottery that would significantly boost the chances that foreigners with advanced degrees from U.S. universities would be able to remain in the country as guest-workers. Trump could go further by expanding the number of H-1B visas, an idea that restrictionists tend to oppose, while increasing the H-1B minimum wage, an idea they generally support. Taken together, these policies might help Trump woo high-wage employers eager to hire talented foreign workers, or at least make them less hostile to his broader agenda.

Of course, this would do little to ease the path of H-1B visas who’d like to permanently settle in the U.S. As it happens, Trump has tweeted that “H1-B holders in the United States can rest assured that changes are soon coming which will bring both simplicity and certainty to your stay, including a potential path to citizenship.” One path to citizenship could be adjusting the allocation of green cards so that aspiring immigrants who’ve already secured remunerative employment in the U.S.—H-1B holders tend to fit the bill—are given higher priority over those who apply purely on the basis of extended family ties. Last year, then-Senator Jeff Flake proposedshifting family-preference visas for the siblings and adult children of U.S. citizens to employment-preference categories that grant green cards on the basis of skills. If Trump really wants “to encourage talented and highly skilled people to pursue career options in the U.S.,” this would be a surefire way to do it.

This doesn’t sound like a terribly Trumpy approach. But the president has charged Jared Kushner with brokering a bipartisan deal on immigration(and for that he deserves our sympathy). No one is especially confident Democrats and Republicans in Congress will devise a border-security compromise over the coming days that President Trump will deem worthy of support, including the president himself. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Trump pegged the chances that a satisfactory deal would be struck at “less than 50-50,” which is to say he’s not quite convinced of his son-in-law’s negotiating prowess.

But if the White House looks beyond the current impasse, to the larger question of how Trump and his allies might reorient the immigration debate, Kushner’s effort could still bear fruit. Although Jared has sometimes been derided as an ingenuous junior plutocrat who makes Howard Schultz look like a centrist Machiavelli, no less an authority than Chris Christie, the former governor of New Jersey and a Trump confidant, has said, “there is simply no one more influential in the White House on the president than Jared Kushner.” And Tuesday night’s speech may reflect his influence.

It’s worth at least considering the possibility that the president has been touting the virtues of H-1B holders for a reason, and that his praise for legal immigrants in the State of the Union was more than a mental lapse.

Stacey Abrams delivered the Democratic Party’s official rebuttal to the State of the Union on Tuesday night. Considered a rising star in the party, Abrams ran for governor in Georgia last year, before losing to Republican Brian Kemp, and is currently weighing another bid for higher office.

Below, the full text of her remarks as delivered.

Good evening, my fellow Americans, and happy Lunar New Year. I’m Stacey Abrams and I'm honored to join the conversation about the state of our union.

Growing up, my family went back and forth between lower middle class and working class, yet even when they came home weary and bone-tired, my parents found a way to show us all who we could be. My librarian mother taught us to love learning. My father, a shipyard worker, put in overtime and extra shifts, and they made sure we volunteered to help others. Later, they both became United Methodist ministers, an expression of the faith that guides us. These were our family values: faith, service, education, and responsibility.

Now, we only had one car, so sometimes my dad had to hitchhike and walk long stretches during the 30-mile trip home from the shipyards. One rainy night, my mom got worried. We piled in the car and went out looking for him, and we eventually found my dad making his way along the road, soaked and shivering in his shirt sleeves. When he got in the car, my mom asked if he had left his coat at work. He explained that he'd given it to a homeless man he'd met on the highway. When we asked why he'd given away his only jacket, my dad turned to us and said, “I knew when I left that man, he'd still be alone, but I could give him my coat, because I knew you were coming for me.”

Our power and strength as Americans lives in our hard work and our belief in more. My family understood firsthand that while success is not guaranteed, we live in a nation where opportunity is possible. But we do not succeed alone. In these United States, when times are tough, we can persevere because our friends and neighbors will come for us. Our first responders will come for us. It is this mantra, this uncommon grace of community that has driven me to become an attorney, a small-business owner, a writer, and most recently, the Democratic nominee for governor of Georgia.

My reason for running was simple. I love our country and its promise of opportunity for all. And I stand here tonight because I hold fast to my father's credo. Together, we are coming for America, for a better America.

[Read: Stacey Abrams’s prescription for a maternal-health crisis]

Just a few weeks ago, I joined volunteers to distribute meals to furloughed federal workers. They waited in line for a box of food and a sliver of hope, since they hadn't received paychecks in weeks. Making livelihoods of our federal workers a pawn for political games is a disgrace. The shutdown was a stunt, engineered by the president of the United States, one that defied every tenet of fairness, and abandoned not just our people, but our values.

For seven years, I led the Democratic Party in the Georgia House of Representatives. I didn't always agree with the Republican speaker or governor, but I understood that our constituents didn't care about our political parties. They cared about their lives. So when we had to negotiate criminal-justice reform or transportation or foster-care improvements, the leaders of our state didn't shut down—we came together and we kept our word. It should be no different in our nation's capital. We may come from different sides of the political aisle, but our joint commitment to the ideals of this nation cannot be negotiable.

Our most urgent work is to realize Americans' dreams of today and tomorrow, to carve a path to independence and prosperity that can last a lifetime. Children deserve an excellent education from cradle to career. We owe them safe schools and the highest standards, regardless of ZIP code. Yet this White House responds timidly, while first graders practice active-shooter drills and the price of higher education grows ever steeper. From now on, our leaders must be willing to tackle gun-safety measures and face the crippling effect of educational loans, to support educators and invest what is necessary to unleash the power of America's greatest minds.

In Georgia and around the country, people are striving for a middle class where a salary truly equals economic security. But instead, families' hopes are being crushed by Republican leadership that ignores real life or just doesn't understand it. Under the current administration, far too many hard-working Americans are falling behind, living paycheck to paycheck, most without labor unions to protect them from even worse harm.

[Read: Why unpaid federal workers can’t strike during a shutdown]

The Republican tax bill rigged the system against working people. Rather than bringing back jobs, plants are closing, layoffs are looming, and wages struggle to keep pace with the actual cost of living. We owe more to the millions of everyday folks who keep our economy running, like truck drivers forced to buy their own rigs, farmers caught in a trade war, small-business owners in search of capital, and domestic workers serving without labor protections—women and men who could thrive if only they had the support and freedom to do so.

We know bipartisanship could craft a 21st century immigration plan, but this administration chooses to cage children and tear families apart. Compassionate treatment at the border is not the same as open borders. President Reagan understood this. President Obama understood this. Americans understand this and the Democrats stand ready to effectively secure our ports and borders. But we must all embrace that from agriculture to health care to entrepreneurship, America is made stronger by the presence of immigrants, not walls.

And rather than suing to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, as Republican attorneys general have, our leaders must protect the progress we've made and commit to expanding health care and lowering cost for everyone. My father has battled prostate cancer for years. To help cover the cost, I found myself sinking deeper into debt, because while you can defer some payments, you can't defer cancer treatment. In this great nation, Americans are skipping blood-pressure pills, forced to choose between buying medicine or paying rent. Maternal mortality rates show that mothers, especially black mothers, risk death to give birth. And in 14 states, including my home state, where a majority want it, our leaders refuse to expand Medicaid, which could save rural hospitals, save economies, and save lives.

We can do so much more: take action on climate change, defend individual liberties with fair-minded judges.

But none of these ambitions are possible without the bedrock guarantee of our right to vote. Let's be clear. Voter suppression is real. From making it harder to register and stay on the rolls, to moving and closing polling places, to rejecting lawful ballots, we can no longer ignore these threats to democracy. While I acknowledge the results of the 2018 election here in Georgia, I did not, and we cannot, accept efforts to undermine our right to vote. That's why I started a nonpartisan organization called Fair Fight, to advocate for voting rights. This is the next battle for our democracy, one where all eligible citizens can have their say about the vision we want for our country. We must reject the cynicism that says allowing every eligible vote to be cast and counted is a power grab.

[Read: The Georgia governor’s race brought voter suppression into full view]

Americans understand that these are the values our brave men and women in uniform and our veterans risk their lives to defend. The foundation of our moral leadership around the globe is free and fair elections, where voters pick their leaders, not where politicians pick their voters.

In this time of division and crisis, we must come together and stand for and with one another. America has stumbled time and again on its quest towards justice and equality. But with each generation, we have revisited our fundamental truths, and where we falter, we make amends. We fought Jim Crow with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. Yet we continue to confront racism from our past and in our present, which is why we must hold everyone, from the highest offices to our own families, accountable for racist words and deeds and call racism what it is: wrong.

America achieved a measure of reproductive justice in Roe v. Wade, but we must never forget: It is immoral to allow politicians to harm women and families, to advance a political agenda. We affirmed marriage equality, and yet the LGBTQ community remains under attack.

So even as I am very disappointed by the president's approach to our problems, I still don't want him to fail. But we need him to tell the truth, and to respect his duties, and respect the extraordinary diversity that defines America. Our progress has always been found in the refuge, in the basic instinct of the American experiment, to do right by our people. And with a renewed commitment to social and economic justice, we will create a stronger America, together. Because America wins by fighting for our shared values against all enemies, foreign and domestic. That is who we are, and when we do so, never wavering, the state of our union will always be strong.

Thank you, and may God bless the United States of America.

President Donald Trump delivered his second State of the Union address Tuesday night before a joint session of Congress. The speech comes as lawmakers are negotiating a deal over border security in an effort to prevent a second government shutdown. The president’s remarks were originally planned for last week, but were postponed after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi disinvited Trump from giving the address while the government was closed.

Below, the full text of Trump’s speech as delivered.

Thank you very much. Madam Speaker, Mr. Vice President, members of Congress, the First Lady of the United States.

And my fellow Americans. We meet tonight at a moment of unlimited potential. As we begin a new Congress, I stand here ready to work with you to achieve historic breakthroughs for all Americans. Millions of our fellow citizens are watching us now gathered in this great chamber hoping that we will govern not as two parties but as one nation.

The agenda I will lay out this evening is not a Republican agenda or a Democrat agenda, it's the agenda of the American people. Many of us have campaigned on the same core promises to defend American jobs and demand fair trade for American workers to rebuild and revitalize our nation's infrastructure, to reduce the price of health care and prescription drugs, to create an immigration system that is safe, lawful, modern, and secure, and to pursue a foreign policy that puts America's interests first. There is a new opportunity in American politics if only we have the courage, together, to seize it.

Victory is not winning for our party. Victory is winning for our country.

This year, America will recognize two important anniversaries that show us the majesty of America's mission and the power of American pride. In June, we mark 75 years since the start of what General Dwight D. Eisenhower called the Great Crusade, the Allied Liberation of Europe in World War II. On D-Day, June 6th, 1944, 15,000 young American men jumped from the sky and 60,000 more stormed in from the sea to save our civilization from tyranny. Here with us tonight are three of those incredible heroes. Private First Class Joseph Reilly, Staff Sergeant Irving Locker, and Sergeant Herman Zeitchik.

Gentlemen, we salute you. In 2019, we also celebrate 50 years since brave young pilots flew a quarter of a million miles through space to plant the American flag on the face of the moon. Half a century later, we are joined by one of the Apollo 11 astronauts who planted that flag, Buzz Aldrin. Thank you, Buzz.

This year, American astronauts will go back to space on American rockets. In the 20th century, America saved freedom, transformed science, redefined the middle class, and, when you get down to it, there's nothing anywhere in the world that can compete with America.

[Read: Trump’s call for unity was never going to be real]

Now we must step boldly and bravely into the next chapter of this great American adventure, and we must create a new standard of living for the 21st century. An amazing quality of life for all of our citizens is within reach. We can make our community safer, our families stronger, our culture richer, our faith deeper, and our middle class bigger and more prosperous than ever before.

But we must reject the politics of revenge, resistance, and retribution and embrace the boundless potential of cooperation, compromise, and the common good. Together we can break decades of political stalemate. We can bridge divisions, heal old wounds, build new coalitions, forge new solutions, and unlock the extraordinary promise of America's future. The decision is ours to make. We must choose between greatness or gridlock, results or resistance, vision or vengeance, incredible progress or pointless destruction. Tonight, I ask you to choose greatness.

Over the last two years, my administration has moved with urgency and historic speed to confront problems neglected by leaders of both parties over many decades. In just over two years, since the election, we have launched an unprecedented economic boom, a boom that has rarely been seen before. There's been nothing like it. We have created 5.3 million new jobs, and, importantly, added 600,000 new manufacturing jobs, something which almost everyone said was impossible to do, but the fact is we are just getting started.

Wages are rising at the fastest pace in decades, and growing for blue-collar workers who I promised to fight for. They're growing faster than anyone else thought possible. Nearly 5 million Americans have been lifted off food stamps.

The U.S. economy is growing almost twice as fast today as when I took office and we are considered far and away the hottest economy anywhere in the world, not even close. Unemployment has reached the lowest rate in over half a century.

African American, Hispanic American, and Asian American unemployment have all reached their lowest levels ever recorded. Unemployment for Americans with disabilities has also reached an all-time low. More people are working now than at any time in the history of our country, 157 million people at work.

We passed a massive tax cut for working families and doubled the child tax credit. We virtually ended the estate tax, or death tax, as it is often called, on small businesses, for ranches, and also for family farms. We eliminated the very unpopular Obamacare individual-mandate penalty. And to give clinically ill patients access to life-saving cures, we passed, very importantly, right to try.

[Read: The GOP is suddenly playing defense on health care]

My administration has cut more regulations in a short period of time than any other administration during its entire tenure. Companies are coming back to our country in large numbers thanks to our historic reductions in taxes and regulations.

And we have unleashed a revolution in American energy. The United States is now the No. 1 producer of oil and natural gas anywhere in the world.

And now, for the first time in 65 years, we are a net exporter of energy. After 24 months of rapid progress, our economy is the envy of the world. Our military is the most powerful on Earth, by far, and America—America is again winning, each and every day.

Members of Congress, the state of our Union is strong. [Some in the House chamber break into “USA” chants.]

That sounds so good. Our country is vibrant, and our economy is thriving like never before. On Friday, it was announced that we added another 304,000 jobs last month alone, almost double the number expected.

An economic miracle is taking place in the United States and the only thing that can stop it are foolish wars, politics, or ridiculous partisan investigations. If there is going to be peace and legislation, there cannot be war and investigation. It just doesn't work that way. We must be united at home to defeat our adversaries abroad. This new era of cooperation can start with finally confirming the more than 300 highly qualified nominees who are still stuck in the Senate, in some cases years and years waiting, not right.

[Read: Trump’s most lasting legacy could be his judges]

The Senate has failed to act on these nominations, which is unfair to the nominees and very unfair to our country. Now is the time for a bipartisan action. Believe it or not, we have already proven that that's possible. In the last Congress, both parties came together to pass unprecedented legislation to confront the opioid crisis, a sweeping new farm bill, historic VA reforms, and after four decades of rejection, we passed VA accountability so that we can finally terminate those who mistreat our wonderful veterans.

And just weeks ago, both parties united for groundbreaking criminal-justice reform. They said it couldn't be done.

Last year, I heard through friends the story of Alice Johnson. I was deeply moved. In 1997, Alice was sentenced to life in prison as a first-time, non-violent drug offender. Over the next 22 years, she became a prison minister, inspiring others to choose a better path. She had a big impact on that prison population and far beyond. Alice's story underscores the disparities and unfairness that can exist in criminal sentencing and the need to remedy this total injustice. She served almost that 22 years, and had expected to be in prison for the remainder of her life. In June, I commuted Alice's sentence. When I saw Alice's beautiful family greet her at the prison gates hugging and kissing and crying and laughing, I knew I did something right. Alice is with us tonight, and she is a terrific woman, terrific. Alice, please.

Alice, thank you for reminding us that we always have the power to shape our own destiny. Thank you very much, Alice, thank you very much.

Inspired by stories like Alice's, my administration worked closely with members of both parties to sign the First Step Act into law. Big deal, big deal.

This legislation reformed sentencing laws that have wrongly and disproportionately harmed the African American community. The First Step Act gives non-violent offenders the chance to reenter society as productive, law-abiding citizens. Now states across the country are following our lead. America is a nation that believes in redemption.

We are also joined tonight by Matthew Charles from Tennessee. In 1996, at the age of 30, Matthew was sentenced to 35 years for selling drugs and related offenses. Over the next two decades, he completed more than 30 Bible studies, became a law clerk, and mentored many of his fellow inmates. Now, Matthew is the very first person to be released from prison under the First Step Act. Matthew, please.

Thank you, Matthew. Welcome home.

Now, Republicans and and Democrats must join forces again to confront an urgent national crisis. Congress has 10 days left to pass a bill that will fund our government, protect our homeland, and secure our very dangerous southern border. Now is the time for Congress to show the world that America is committed to ending illegal immigration and putting the ruthless coyotes, cartels, drug dealers, and human traffickers out of business.

As we speak, large organized caravans are on the march to the United States. We have just heard that Mexican cities, in order to remove the illegal immigrants from their communities, are getting trucks and buses to bring them up to our country in areas where there is little border protection. I have ordered another 3,750 troops to our southern border to prepare for this tremendous onslaught. This is a moral issue. The lawless state of our southern border is a threat to the safety, security, and financial well-being of all Americans. We have a moral duty to create an immigration system that protects the lives and jobs of our citizens. This includes our obligation to the millions of immigrants living here today who followed the rules and respected our laws. Legal immigrants enrich our nation and strengthen our society in countless ways.

[Read: A border is not a wall]