ABUJA—Politics in Nigeria can be like General Hospital or Coronation Street—a long-running soap opera in which the cast rarely changes. Except here, it’s all about the military.

In 1979, General Olusegun Obasanjo handed over power to Nigeria’s first democratically elected government. The parade ending 13 years of military rule was organized by a young colonel, Abdusalam Abubakar. The elected administration was ousted in 1983, in a coup led by General Muhammadu Buhari, and the military remained in charge until 1999, when Abubakar, who by then had taken the reins, stood down in favor of Obasanjo, who had run for president as a civilian. Buhari himself won Nigeria’s most recent election (as a civilian) and is currently running for reelection against Obasanjo’s former vice president, with voting taking place Saturday.

In short, the same band of characters has run this country of about 180 million people for upwards of half a century. And while Nigeria is entering its third decade of uninterrupted democracy, it does so with the omnipresent influence of the military in its politics. Like in Egypt or Pakistan—countries where elected leaders are often overshadowed by senior officers—the military plays an outsize role here, and not just in the form of prospective political candidates. Former officers hold seats in private-sector boardrooms and bankroll political campaigns, too. The longer that continues, the harder it becomes to separate the civilian leadership from the military’s top brass, and the worse the impact on public life in Nigeria.

[Read: Nigeria democratically elects its former dictator]

“As a result of the kind of funds that they had access to while the military was in power, and the fact that they ingratiated themselves into Nigeria's power structures, they wield a lot of access to Nigeria's patronage networks,” Cheta Nwanze, the head of research at the Lagos-based SBM Intelligence, a risk advisory firm, told me about the military’s influence.

In 48 of the 58 years since Nigeria won independence from Britain, it has been led either by a general or by someone with a link to the military. The exceptions were in the first five and half years of Nigeria’s modern existence, and then during the leadership of Goodluck Jonathan. Jonathan, who made history in 2015 as the only incumbent in Nigeria to lose an election, only rose to the presidency when his boss, Umaru Yar’Adua (the younger brother of, you guessed it, a general) died of an illness in 2010.

And in the business world, military officials have had their pick of jobs, from controlling stakes in oil fields to executive roles in shipping companies and defense contractors, as well as board seats on charities. Three of the biggest farms nationwide belong, respectively, to two ex-generals, one of them former President Abubakar, and a one-time air vice-marshal. It doesn’t end there: Just months after his airline lost its license and went bust, another retired general was appointed ambassador to South Africa, while Yar’Adua’s elder brother was, until his death, a major shareholder in a Nigerian bank. In 2010, one former army chief of staff told a stunned public gathering that he made $500 million from oil wells (to say nothing of his board positions with a telecom firm and a beverage manufacturer).

The enormous role the military holds in public life here has consequences beyond the positions officers hold, and is affecting both how the law is applied and how Nigerians view their own democracy.

[Read: How to undermine a democracy]

As president, Obasanjo routinely instigated impeachments of state governors who refused to do his bidding, and attempted, unsuccessfully, to extend his tenure beyond the two terms presidents here are limited to (a former chairman of Nigeria’s human-rights watchdog has claimed that Obasanjo tried to bribe lawmakers to do so). Buhari, whose deputy is a law professor, has shown a spectacular disdain for the courts. Under his watch, secret police arrested judges in a midnight raid and detained journalists. In January 2019, the president suspended the chief justice, an unconstitutional move. And last summer, he told a room full of lawyers, including the now-suspended judge, that the “rule of law must be subject to the supremacy of the nation’s security and national interest.”

Support for elections remains high here—an Afrobarometer poll this month showed that 72 percent of Nigerians believe elections are the best way to choose the country’s leaders, but that figure was down from 82 percent in 2003. And public backing for democratic norms appears to be declining. Some Buhari supporters have suggested that the constitution be suspended temporarily for the president to enact reforms, arguing in favor of a strongman in the face of “unruly behavior”, as Buhari himself put it during his first address to the nation, on October 1, 2015—Nigeria’s Independence Day. Older Nigerians point to coups as useful ways to displace corrupt politicians, or reference Rwanda and Ghana (under Paul Kagame and Jerry Rawlings, respectively, both of whom commanded armed forces) as examples of strongman states that Nigeria could learn from. Expressions and mannerisms from the days of military rule are still part of the democratic lexicon; phrases such as with immediate effect, an inference that orders must be implemented without procedural hurdles, are commonplace on TV and radio.

“If you look at African history, you will come to the conclusion that even in cases where military intervention may have been a quick fix in a particular context, in the long run, strongman rule was extremely detrimental to our continent,” Chris Fomunyoh, the Africa director of the National Democratic Institute, which has observed all national elections in Nigeria since 1999, told me. “In today’s Africa, with youths who see themselves as citizens of the world and who aspire to have [the] same liberties as elsewhere, there can be no rationale for throwing them and the continent back to the dark days of strongman rule.”

There are, however, positives. Though the military has a significant impact on Nigeria’s politics, no serving officer has ruled the country since 1999. When Jonathan lost to Buhari four years ago, he conceded without much drama; Buhari himself could be defeated in Saturday’s elections. Fellow West African countries such as Ghana and Gambia have shown a commitment to democracy, which can itself have a positive knock-on effect.

But more needs to be done. Nigeria’s political structure has thrust too much authority into the hands of the president, and few updates have been made to the country’s constitution, which is little changed from when the military handed over power. “Nigeria’s constitution … has managed to over-concentrate power at the center, à la military command, rendering other operating units weak and ineffective,” says Adewunmi Emoruwa, an Abuja-based analyst who is the chief operating officer of the Nigerian consulting firm Gatefield. The country’s leaders, military or not, are also an elderly bunch. Legislation has been passed cutting the minimum age required to run for state and federal positions and, buoyed by this, a 35-year-old MIT graduate is contesting a senatorial race in Lagos, but Buhari is 76 and his challenger, Atiku Abubakar, is 72.

“I am still optimistic about Nigeria,” the National Democratic Institute’s Fomunyoh told me, before adding that the country still has to focus on strengthening its democratic structure. “You have to improve it—that’s a natural component of the democratic process.”

About two years ago, Republican Representative Devin Nunes, then the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, went on a “midnight run” to the White House that changed everything.

Nunes embarked on the late-night excursion just as the panel he oversaw was opening an investigation into President Donald Trump’s campaign and Russia. He then used the information he’d obtained from White House sources to allege surveillance abuses by President Barack Obama’s administration, raising critics’ concerns that his chumminess with the administration delegitimized the House’s Russia probe. It was also a sign, critics said, that the committee couldn’t operate in a bipartisan way.

So the public looked to the Senate Intelligence Committee for a comprehensive, bipartisan examination of Trump’s Russia ties—a reputation the panel’s Republican chair, Richard Burr, who had served as a senior national security advisor to the Trump campaign, has largely upheld by keeping the investigation scandal-free. “Nothing in this town stays classified or secret forever,” Burr told the Associated Press last August. “And at some point somebody’s going to go back and do a review. And I’d love not to be the one that chaired the committee when somebody says, ‘well, boy, you missed this.’ So we’ve tried to be pretty thorough in how we’ve done it.”

Though Burr and Mark Warner, the committee’s Democratic vice-chairman, have largely agreed on the parameters of the investigation, they have recently begun to disagree more publicly on what the facts they’ve collected add up to: Conspiracy? A series of coincidences and bad decisions? Or something in between?

The new Democratic chair of the House Intelligence Committee, Adam Schiff, does not believe those questions can be answered without a thorough examination of Trump’s financial history and his potential entanglements with Russian money launderers, especially given new revelations about Trump’s efforts to pursue a multimillion-dollar real-estate deal in Moscow in 2016. So he has revived the panel’s floundering Russia probe by hiring upwards of a dozen dedicated staffers with expertise in corruption or illicit finance, or prosecutorial experience. That brings the total number of investigators, which could increase, to 24 on the House panel alone. Many are bringing specific skills to the committee that the nine staffers working on the Senate’s Russia probe—despite their extensive intelligence-community experience—do not have, according to two people with direct knowledge of that committee’s work.

The reinvigorated House probe intends to pursue avenues of inquiry that may have been overlooked by the Republican-led House Intelligence Committee investigation, including the substance of Trump’s closed-door conversations with Russian President Vladimir Putin over the past two years. A particular emphasis will also be placed on Deutsche Bank—the Trump family’s bank of choice for decades, which was fined in 2017 over a $10 billion Russian money-laundering scheme involving its Moscow, New York, and London branches. “The concern about Deutsche Bank is that they have a history of laundering Russian money,” Schiff told NBC in December. “This, apparently, was the one bank that was willing to do business with the Trump Organization. If this is a form of compromise, it needs to be exposed.” Deutsche Bank representatives said last month that the bank was working with the House Intelligence and Financial Services committees to “determine the best and most appropriate way of assisting them in their official oversight functions.”

Special Counsel Robert Mueller is pursuing a separate federal investigation into a potential conspiracy between the campaign and Russia in 2016. While he can issue indictments, the congressional committees can pursue a broader inquiry assessing misconduct that may not rise to the level of criminal activity.

***

It is undeniable that the Senate Intelligence Committee has traditionally been far more unified than its House counterpart, mostly by virtue of longer term limits and different rules. The committee produced important bipartisan reports over the past two years, including one last July that reaffirmed the intelligence community’s assessment that Russia worked to harm Hillary Clinton’s candidacy in 2016, and another that provided a sweeping analysis of Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns. The panel has also interviewed more than 200 witnesses and sifted through hundreds of thousands of pages of documents.

Nevertheless, the bipartisan ground on which the Senate purported to have built its inquiry may be cracking. On Tuesday, Warner said he disagreed with Burr’s claim that the probe had found no “direct evidence” of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia. The comment left some legal experts perplexed, too. “I don’t think I’ve ever had a case where I have direct evidence of a conspiracy,” said Chuck Rosenberg, a Justice Department veteran who served as former FBI Director James Comey’s chief of staff until 2015. “If there is snow on your front lawn, you can safely conclude that it snowed,” Rosenberg told me. “Is that direct evidence? No. It’s circumstantial—someone could’ve driven up to your house and thrown snow on your lawn. But that’s unlikely. The law treats circumstantial and direct evidence as being of equal weight.”

Some Democratic aides were also confused by Burr’s recent claim that a key witness in the probe, the former British spy Christopher Steele, had not responded to the committee’s attempts to engage with him. In fact, Steele submitted written answers to the panel last August, two people familiar with the matter who requested anonymity to discuss the investigation told me.

The Senate’s subpoena for his testimony was dropped shortly thereafter—indicating that the senators were satisfied enough with his responses that they weren’t planning to compel further testimony.

Moreover, the House Democrats’ willingness to launch a full investigation into Trump’s financial history may not be “politically realistic” in the Republican-controlled Senate, said one of the people with direct knowledge of the Senate’s investigation. “The follow-the-money pieces of this are really important, but the question is, who is best positioned to do it?” this person said, referring to the committee’s jurisdictional limitations. The source added that it was “absolutely fair” to criticize the panel’s decision not to bring in outside investigators with expertise in financial investigations, ethics, and money laundering. “But I give full credit to Burr and Warner for keeping this investigation bipartisan, in a very difficult environment on such a fraught issue,” the source said.

Burr recently defended the decision not to hire outside investigators, telling CBS that they “would’ve never had access to some of the documents that we were able to access from the intelligence community.” A spokesperson for Warner declined to comment on whether the senator agreed with that assessment. A Republican committee aide, who requested anonymity to discuss the panel’s staff, reiterated that Burr has “full confidence in the bipartisan investigative staff, who were selected by both himself and the vice chairman. Over the last two years, members of the committee on both sides of the aisle have praised the investigators’ work and integrity.”

But Ryan Goodman, an expert in national-security law, told me he saw “red flags” in the way the investigation was being carried out, including the chairman’s “failure to hire outside staff with professional expertise and experience in complex investigations, and the failure to use the subpoena power to easily obtain financial records from entities like Deutsche Bank.”

“A successful congressional inquiry like this can stand or fall on the size and investigative skills of its staff,” Goodman added.

Another contention in the Senate’s inquiry is the extent to which Steele, the retired MI6 officer who in 2016 authored a collection of memos known as the Trump-Russia dossier, has cooperated with the committee. The body had prepared a subpoena for Steele’s testimony in March 2018, but withdrew it after he provided his written testimony in August. Investigators who have traveled to London since then have not approached Steele for an interview, according to Steele’s lawyer, who declined to be identified due to sensitivities surrounding the probe. Burr suggested in an interview with CBS last week that Steele remained out of reach. “We’ve made multiple attempts,” to elicit a response, Burr said.

Steele’s lawyer said that was “flatly not true,” and that the committee had actually agreed in writing not to seek further information from Steele after he submitted his written testimony. The panel has not reached out to request another interview, the lawyer said.

The Republican committee aide did not dispute that the panel had received Steele’s statements. But the aide said the committee had “made clear to Mr. Steele and his attorney that there is no substitute for a face-to-face interview when it comes to answering some of the committee’s most pressing questions.” A spokesperson for Warner confirmed that the committee “would like to speak with Mr. Steele.” The committee did not respond to Steele’s lawyer’s comments.

The dossier, which alleges serious misconduct and conspiracy between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin in 2016, was presented to Trump by the nation’s top intelligence officials in January 2017. Trump dismissed it as “phony,” but many of the document’s core allegations appear to align with events during the campaign and are slowly being corroborated.

It’s getting harder for the Senate committee’s Republicans and Democrats to remain in step as they near the point where they’ll have to draw conclusions from their findings. One Democratic Senate Intelligence Committee aide put it simply: “There is a common set of facts, and a disagreement on what those facts mean. We are closer to the end than to the beginning, but we are not wrapping up.”

Amazon announced Thursday that its expansion of a second headquarters in New York wouldn’t happen after all (its plans for the D.C. suburbs remain intact). The deal fell through after intense opposition from activists and politicians, the latest sign that cities are souring on the tech industry. That this activism somehow proved victorious could signal the start of a broader movement nationwide against the type of lavish tax incentives that lured Amazon to New York in the first place. Detractors might be on to something, argues Derek Thompson: This type of corporate welfare rarely is worth the cost for cities, and the tens of thousands of new Amazon workers would’ve exacerbated New York City’s spiraling housing-affordability crisis.

Thursday marks one year since the Parkland, Florida school shooting, which left 17 students dead and dozens more injured. After hearing shots, Sarah Lerner, an English and journalism teacher at the school, recalls that she huddled in her classroom with a group of her students for several hours. In the foggy year since, a sense of normalcy has been elusive—especially when she returned to school just 9 days later. She’s not the only one who found the process of going back to school traumatizing; after the shooting, some of the students were gutted to see the empty desks of lost classmates. Post-Parkland, there’s still one big question flummoxing investigators: How to prevent the next one.

Then-acting FBI director Andrew McCabe is now sharing details on what he considers the ethical and moral lines President Trump crossed during his tenure, in an exclusive adaptation from his forthcoming book. McCabe recalls that on his first full day in the acting director role, shortly after the President had fired then-director James Comey, he received a call from the White House; the president wanted to chat. Like his former boss, McCabe said he took contemporaneous notes of the conversation.

The White House said Trump will sign a compromise bill to avert a government shutdown but will take an “executive action,” including declaring a national emergency, to bypass Congress to secure funding for a U.S.-Mexico border wall. The president has dangled the prospect of declaring a national emergency for weeks—here’s what powers might be afforded to a president under such a declaration. (It’s also worth remembering that the U.S. currently is under roughly 30 other ongoing national emergencies, one of which was issued by President Jimmy Carter a full four decades ago.)

—Saahil Desai and Shan Wang

Evening Reads (Erin McCluskey)

(Erin McCluskey)After a married couple found out that the wife had terminal breast cancer, they made an unusual choice: keeping it a secret from the kids.

“Marla and I launched our stealth treatment strategy together: Everything would be tried; little would be shared. We saw no need to alarm friends, worry relatives, or derail the girls. Subterfuge was essential for survival—not just the literal, existential kind, but survival of the spirit. Our kids would not be robbed of stability; protecting their sense of the ordinary was everything. The ground would stay steady, and we would extend the runway for as long as possible.”

(Illustration: The Atlantic)

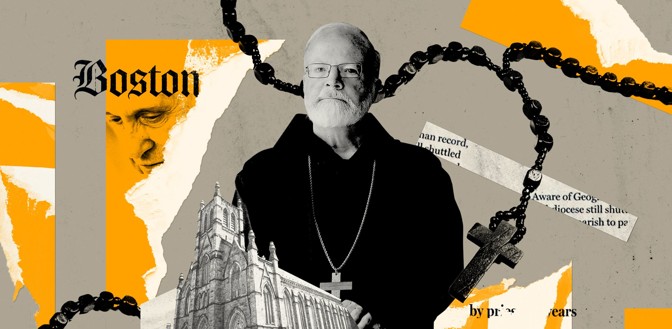

Cardinal Seán O’Malley, who runs the Archdiocese of Boston, is one of the closest confidantes of the pope, yet he has struggled in his quest to remedy the Church’s lingering sexual-abuse problem:

“In an interview on a recent cold morning in Boston, the cardinal spoke about the progress he believes the Church, and Pope Francis, have made in recent years, and what’s still lacking. He detailed his proposal to establish Vatican tribunals to deal with bishops accused of wrongdoing—one of the major problems the Church has yet to address. The pope ‘was convinced to do it another way,’ O’Malley said. ‘We’re still waiting for the procedures to be clearly articulated.’ He often described problems in the Church passively, without directly assigning agency or fault. ”

Urban Developments

(Photo: Warren M. Winterbottom / AP)

Our partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing urban dwellers around the world. Gracie McKenzie shares today’s top stories:

Why did California Governor Gavin Newsom scale back the quest for high-speed rail between San Francisco and Los Angeles? The new plan, Laura Bliss writes, risks turning the transportation project into an economic-development tool.

Looking for love this Valentine’s Day? Apparently, America left its heart in San Francisco: Residents of the Bay Area may be among the "most romantic" in the country, according to data from OkCupid.

In urban marketing campaigns, cities often focus on the same basic ingredients: hipster coffee shops, bike lanes, and farm-to-table restaurants. City branding needs a shot of creativity, Aaron Renn writes—it’s time to showcase distinct identities of place.

Keep up with the most pressing, interesting, and important city stories of the day. Subscribe to the CityLab Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here.

Comments, questions, typos? Email newsletters editor Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos recently accused the National Enquirer of “extortion and blackmail” over private photos of him obtained by the tabloid. In a Medium post, Bezos shared emails from the Enquirer that threaten to publish those photos unless he accedes to their demands. How did a celebrity magazine get into the rough and tumble world of extortion?

On this week’s Radio Atlantic, Alex Wagner is joined by Jeffrey Toobin, New Yorker staff writer and CNN’s Chief Legal Analyst. He shares insights from his 2017 profile of the man who runs the tabloid. How did the National Enquirer become what it is today? Why does it pay to silence stories about Donald Trump? And why is it at war with Jeff Bezos?

Listen for:

The unexpected history of the tabloid and what Jeffrey Toobin learned from spending time with David Pecker, CEO of the Enquirer’s parent company An episode ten years ago just like L'Affaire Bezos — except the celebrity subject of the Enquirer’s photos did as the tabloid asked How the Enquirer’s actions could impact journalism. As Bob Bauer, former White House counsel for Obama, put it in The Atlantic: Can Freedom of the Press Survive David Pecker?Voices:

Alex Wagner (@AlexWagner) Jeffrey Toobin (@JeffreyToobin)It’s Thursday, February 14. President Donald Trump plans to sign the congressional deal to avert a government shutdown, but the White House says Trump will “take another executive action—including a national emergency” in order to bypass Congress for border-wall funding. (Here’s a refresher on the legal showdown that might result.)

Meanwhile, William Barr was sworn in as the new attorney general after being confirmed by the Senate earlier today. Here’s what else we’re following:

“A Deliberate Liar”: Andrew McCabe writes in an exclusive book excerpt for The Atlantic that “the president and his men were trying to work me the way a criminal brigade would operate.” The former acting FBI director describes interactions with Trump himself—including when the president called him on an unsecured phone line to talk about his firing of former FBI Director James Comey—and his conversations with deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein about protecting ongoing investigations into Russian interference.

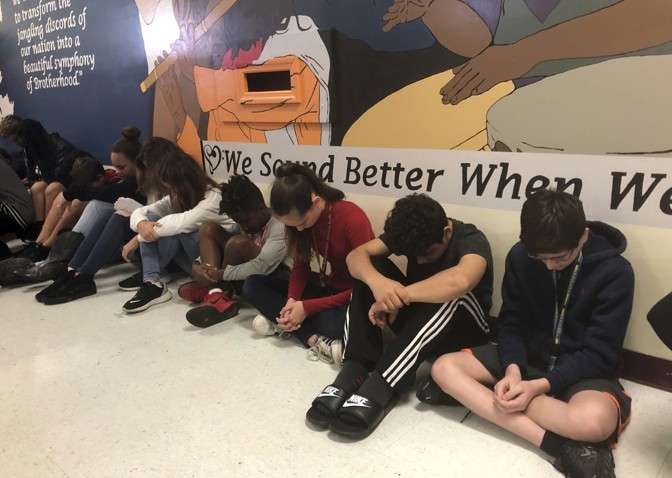

One Year After Parkland: How have students tried to recover from the trauma of a mass shooting, while still keeping the memory of their classmates alive? And although schools across the country have worked to improve security, administrators can only do so much to prevent another attack, Adam Harris reports.

Is This Just Fantasy?: In a speech yesterday at a gathering of police chiefs, Trump praised Art Acevedo, the police chief of Houston, Texas. The only problem? Acevedo has been consistently critical of Trump. His criticisms show that Trump’s “caricatured view of a uniformly macho, tough-on-crime law-enforcement establishment doesn’t totally match reality,” writes David A. Graham.

An Inside Look at the Church in Crisis: Cardinal Seán O’Malley has been at the forefront of the Catholic Church’s response to clergy sexual abuse for years. In the lead-up to next week’s gathering of top bishops at the Vatican to take steps toward addressing the crisis, O’Malley, in an exclusive interview, told The Atlantic’s Emma Green that he has been frustrated by the bishops’ inability to respond to the scandals that have rocked the Church for decades: “Every time we thought we were rounding a corner, there will be another explosion.”

2020 Vision: How many people are running for president anyway? Warren, Booker, Harris? Biden, Sanders, Clinton? What about de Blasio? O’Rourke? How does one pronounce Buttigieg? Here are the answers to all your most fundamental 2020 questions.

— Olivia Paschal and Madeleine Carlisle

Snapshot

Students at Seminole Middle School in Plantation, Florida, participate in a moment of silence for the 14 students and three staff members killed one year ago at the nearby Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. They are sitting in front of a new mural, depicting musicians from around the world, that was dedicated to the shooting victims. (Terry Spencer / AP)

Ideas From The AtlanticAmazon Got Exactly What It Deserved—And So Did New York (Derek Thompson)

“New York City doesn’t need an Amazon headquarters to be the global capital of advertising and retail, and Amazon doesn’t need New York subsidies to expand its footprint in the city. The larger truth is that corporate subsidies, including the $3 billion package offered to Amazon, are often pernicious and usually pointless.” → Read on.

How the Parkland Shooting Changed My Life (Sarah Lerner)

“I went to school the morning of February 14, 2018, to give a quiz to my senior English classes. I joked that I was ruining their Valentine’s Day by giving them the quiz. To make them smile, I put Hershey’s Kisses on their desks. Later that day, 20 minutes before school ended, my world changed forever. I left school shattered, broken, lost.” → Read on.

John Dingell Was a Gift to America (Norm Ornstein)

“This country is a better, more just, and cleaner place than it would have been without Dingell’s service in Congress. Which makes our current backsliding even more frustrating.” → Read on.

What Will Trump Do If He Realizes He’s Lost the Shutdown Fight? (Peter Beinart)

“Preventing the cycle from starting all over again may require allowing Trump to maintain his delusions of grandeur. It’s like dealing with small children: It’s safer to let them think they’ve won than endure the temper tantrum that will ensue if they realize they’ve lost.” → Read on.

◆A Year After Parkland, a Family Searches for Closure (Gabby Deutch, Politico)

◆ ‘Here’s the System; It Sucks’: Meet the Hill Staffers Hired by Ocasio-Cortez to Upend Washington (Jeff Stein, The Washington Post)

◆ TVA to Close Coal-Run Plants in Kentucky, Tennessee (Jim Gaines, Knoxville News Sentinel)

◆Green New Deal Activists Shift Focus to Vulnerable Republicans Ahead of Senate Vote (Alexander C. Kaufman, Huffington Post)

◆Texas Student After School Shootings: ‘I Feel We Are Always on Guard’ (Diane Smith and Anna M. Tinsley, Fort Worth Star-Telegram)

◆Inside the Largest and Most Controversial Shelter for Migrant Children in the U.S. (John Burnett, NPR)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here. We have many other free email newsletters on a variety of other topics. Find the full list here.

When the filmmaker Sindha Agha first went to the doctor about her pain, she experienced a phenomenon familiar to many women—she was not taken seriously. Then, it happened again. And again.

“It took me nearly 15 years of going to doctor after doctor to finally receive adequate treatment,” Agha told The Atlantic. “It's absurd that most people have never heard of a condition that one in 10 women have.”

Agha was ultimately diagnosed with endometriosis, a condition in which the tissue that lines the inside of the uterus begins to grow outside, spreading to the ovaries, the fallopian tubes, and even the pelvis. Women with endometriosis often experience severe pain, most commonly during their menstrual cycle or while having intercourse. Many seek treatment, only to be sent home with Tylenol and a shrug. Instances of the gaslighting of women’s pain litter the history of health care.

Agha’s powerful short documentary tells one such story. A woman whom Agha connected with through an online endometriosis support network recounts her experience of painful sex and demurring doctors. Like Agha, it took years for the woman to have her pain acknowledged. We hear her story over evocative, stylized imagery.

“I wanted the visuals to make viewers experience something viscerally,” Agha said. “I can't physically transport you into the body of someone with endometriosis, but maybe if we poke a hundred nails into some Jell-O, you might get an idea.” Agha underwent a process of “unnerving free association” to create the specific visuals. “I'd think of an object, like a sheet cake, and think of what I wouldn't want to see happen to it. And then I'd do that.” She hoped to represent the sense of discomfort that women with endometriosis often feel inside their own bodies.

Agha believes that the overall cultural shift toward believing women should extend into the doctor's office. “When women say they're in pain,” she said, “they deserve to be believed.”

This film originally appeared on BBC Three.

An established musician lavishes an unknown one with praise and career help: recording sessions, songwriting advice, a spot on a tour. What to call the two of them? Boss and employee? Nothing so straightforward. Collaborative equals? Not if one’s success depends on the other’s largesse. Really they’re mentor and mentee, a central arrangement in pop-music mythology, most recently given Hollywood glorification in A Star Is Born.

But in real life, that story can involve the mentor exploiting their power for sex, and without actually helping the mentee. The #MeToo tales to emerge in the music industry have, to an overwhelming extent, exposed men who tried to trade access to the music industry for access to a musician’s body. Many of the women allegedly abused by R. Kelly were young, aspiring singers lured into his orbit by the prospect of professional development. It happens in formal arrangements, too: Among the women alleging rape by Russell Simmons is Tina Baker, an artist he managed. Now, the accusations surfacing about the rocker Ryan Adams offer a stark reminder of how such mentorship can be weaponized.

Adams’s country-tinged rock won acclaim and sold hundreds of thousands of albums in the early 2000s, and since then he’s been an alternative-music fixture, releasing a steady stream of songs and engaging in splashy collaborations. A New York Times article published on Wednesday quotes multiple women—some famous and some not—who allege Adams dangled career boosts only to then pursue sex. Again and again, that pursuit is reported to have resulted in exactly the opposite of the fruitful partnership Adams promised. These women say he sabotaged their ambitions.

Ava, a bass player who was 14 when Adams reached out on Twitter, says his texts and video messages mingled talk of recording together with explicit come-ons. Phoebe Bridgers, a now-acclaimed singer-songwriter, received promotion, distribution, and production assistance from Adams—and says their relationship quickly turned not only romantic but also emotionally abusive. Another musician, Courtney Jaye, says she received a Twitter message from Adams asking her to jam with him, but when they met up, Adams made physical advances on her.

There is also Mandy Moore, the onetime teen pop star who now acts on the NBC show This Is Us. She and Adams were married for six years. During that time, she alleges he took over her music career, promising to record her next album—while shooing her away from other music producers—but never following through. Moore reports that belittling comments (“you’re not a real musician”) intermingled with other forms of harsh treatment by Adams. The experience resembled the emotional abuse alleged by another Adams ex, Megan Butterworth.

In many of the cases, the women describe Adams damaging or derailing their careers. Jaye told the Times, “Something changed in me … It made me just not want to make music.” Said Moore: “His controlling behavior essentially did block my ability to make new connections in the industry during a very pivotal and potentially lucrative time—my entire mid-to-late 20s.” Regarding Ava, the Times writes, “the idea that she would be objectified or have to sleep with people to get ahead ‘just totally put me off to the whole idea’ of being a musician, she said. She never played another gig.”

Adams’s lawyer has denied the allegations and called some of them “grousing by disgruntled individuals.” Adams took a somewhat more conciliatory tone on Twitter, writing, “To anyone I have ever hurt, however unintentionally, I apologize deeply and unreservedly.” But he added, “the picture that this article paints is upsettingly inaccurate. Some of its details are misrepresented; some are exaggerated; some are outright false. I would never have inappropriate interactions with someone I thought was underage. Period.” He also tweeted this: “As someone who has always tried to spread joy through my music and my life, hearing that some people believe I caused them pain saddens me greatly.”

As someone who has always tried to spread joy through my music: It’s a statement that resurfaces old bromides about creativity and genius. Over the years, Adams’s general public presentation has been that of a hard-partying bad boy who’s also arguably the dean of alternative rock, prolific with albums and team-ups and covers. The allegations in the Times piece draw a clear line between his clout and his reported ability to manipulate and hold back women. “Music was a point of control for him,” Moore said, and the pattern even predates the Times story. When Moore in 2017 spoke publicly about their divorce, Adams hit back on social media by mocking her as a cultural lightweight, someone he was now embarrassed of. In one tweet he wrote, “She didn’t like the Melvins or BladeRunner. Doomed from the start … .” Another compared being married to Moore to being “stuck to the spiritual equivalent of a soggy piece of cardboard.”

The dichotomy he drew in those tweets—which he later apologized for—painted him as a serious man who deigned to associate with an unserious woman. It is a deeply ingrained idea in pop culture, bound up with the way mentor-mentee relationships between men and women are so easily and destructively sexualized. Take the 1960s story of the singer Marianne Faithfull. She found entrée into the industry through the Rolling Stones, whose manager referred to her as an “angel with big tits.” In 1967, she became the object of public mockery when she was discovered wearing only a fur rug during a police bust of Keith Richards’s home. It took a decade before she returned to music-making, and her string of profoundly moving albums has continued up through the present. “The whole thing of being considered a chick on the arm of a great rock star is an insult to me,” she said in 2014.

You see glimmers of the alleged Ryan Adams pattern even in A Star Is Born, a basket of beloved tropes about men conferring greatness upon unknown women—and falling in love with their bodies at the same time. Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga’s version explicitly plays with the notion of gravitas-steeped guys who first lend credibility to women, and then try to control them by calling them frivolous and putting the woman’s professional goals in tension with their personal relationship. The fable Hollywood clearly wants to tell is how a woman can benefit from a man’s affections, and then transcend his resentment and vindictiveness. But the reality, as Adams’s accusers hint, doesn’t often work out that way.

It’s of course not just a myth that men can help aspiring women succeed—it’s simply a reality based on who holds power. #MeToo-era conversations about why it’s been so hard for women to “step up” into successful music careers make clear that the story told by the Adams allegations is part of a systemic problem. How to unwind it? For many musicians, the workplace has no formalized hierarchy or HR departments. When an unsigned artist gets harassed by the rock star who’s positioned himself as her A&R man, producer, and promoter, who does she complain to? When a consensual relationship devolves into manipulation and career undermining, what’s the recourse?

The law only gets you so far: The Times story overtly suggests one potential criminal violation, regarding the case of Ava, who Adams’s attorney says he didn’t know was underage. For Moore, Bridges, Butterworth, and Jaye, though, the alleged offenses are to the women’s careers and senses of self. Protecting other aspiring artists will take the rewriting of myths and the naming and shaming of supposed heroes. It will also take replacing some of those heroes from the ranks of women who’d otherwise be thwarted.

Summertime in Antarctica is winding down these days, with the first sunset of the year coming to the South Pole in about two weeks. The people living and working at Antarctic coastal stations were able to experience a few weeks of constant daylight around Christmastime. Gathered below, recent images of the Antarctic landscape, wildlife, and research facilities, and some of the work taking place there.

Amazon said on Thursday that it will cancel its plans to add a second corporate headquarters in New York City. The company had pledged to build a campus in Queens’ Long Island City in exchange for $3 billion in subsidies.

In a statement, Amazon blamed local politicians for the reversal. “For Amazon, the commitment to build a new headquarters requires positive, collaborative relationships with state and local elected officials who will be supportive over the long-term,” the statement read. “A number of state and local politicians have made it clear that they oppose our presence and will not work with us to build the type of relationships that are required to go forward with the project.”

In a period of growing antipathy toward billionaires, Amazon’s corporate-welfare haul struck many—including me—as a gratuitous gift to a trillion-dollar company that was probably going to keep adding thousands of jobs to the New York region anyway. The company has more than 5,000 employees in the five boroughs, including 2,500 at a Staten Island fulfillment center and at least one thousand more in the Manhattan West office building.

[Read: Amazon’s HQ2 will only worsen America’s “great divergence”]

At first, Amazon seemed to withstand the backlash, comforted by polls showing that the deal enjoyed broad support. A recent poll from Siena College Research Institute found that 56 percent of voters statewide support the Amazon deal, including a majority of union households and people between the age of 18 and 34.

But over time, Amazon’s patience wore thin. Executives were reportedly livid at the nomination of the Queens state Senator Michael N. Gianaris, an outspoken opponent of the deal, to a Public Authorities Control Board that would give him power to “effectively kill the project.” Amazon leaders were grilled at a February city council meeting about the company’s resistance toward unions and the working conditions of its fulfillment centers. (By contrast, Virginia—the other winner of the HQ2 sweepstakes—has embraced Amazon with open arms, and the state has already authorized $750 million in state subsidies for its Crystal City headquarters.) Last week, The Washington Post (which is owned by the Amazon CEO, Jeff Bezos) reported that the retailer was having second thoughts about its New York campus, given the level of opposition from local politicians, advocacy groups, and the media.

Within a week, the company officially canceled the project.

The company said it does not plan to reopen the HQ2 search. “We will proceed as planned in Northern Virginia and Nashville,” the statement said.

The most obvious losers in Amazon’s reversal are real-estate speculators. In November, The Wall Street Journal reported that brokers embarked on a “condo gold rush” in anticipation of the Queens campus construction. “This is like a gift from the gods for the Long Island City condo market,” one realtor told the Journal. Alas, the gods, like the billionaires, giveth and taketh away.

[Annie Lowrey: Amazon was never going to choose Detroit]

But it is not clear that either New York City or Amazon will suffer with this announcement. In fact, it is more likely that neither the city’s nor the company’s economic trajectory will be materially altered. New York City doesn’t need an Amazon headquarters to be the global capital of advertising and retail, and Amazon doesn’t need New York subsidies to expand its footprint in the city.

The larger truth is that corporate subsidies, including the $3 billion package offered to Amazon, are often pernicious and usually pointless. Studies show that these sorts of measures “have no discernible impact on firm expansion, measured by job creation.” Yet every year, local governments spend more than $90 billion to move headquarters and factories between states, a wasteful zero-sum exercise whose cost is more than the federal government spends on affordable housing, education, or infrastructure. In the most garish example of corporate-welfare absurdity, Foxconn, the Taiwanese manufacturing company, solicited up to $4 billion in subsidies from Wisconsin in exchange for a factory and tens of thousands of workers. Now it’s an open question whether that facility will ever get built.

But even the less garish examples are galling. New York City doesn’t have an employment problem; it has a housing-affordability problem. Yet the original language of the Amazon deal used tax breaks that might have gone to infrastructure or low-income housing investment in the Long Island City region. While it’s hard to draw a direct line between corporate handouts and foregone public spending, the fact that states and cities cannot run persistent deficits or print their own currency, like the federal government can, implies that tax dollars lavished on corporations limit the amount of money available to other public projects. Meanwhile, the New York City subway is a disaster, and tuition is rising at the City University of New York system.

“I am a bit surprised that Amazon pulled out,” Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, told me by email. “The unrest over inequality and gentrification is starting to have tangible business consequences.” The irony is that the quasi-socialist revolution behind this unrest has voided a corporate-welfare deal that is more corporate cronyism than capitalism. It has taken far-left protesters to inject a measure of sanity into the free market.

Well, that didn’t take long.

Amazon announced today that it was “not moving forward” with the plans to build out a massive corporate office, which it called HQ2, in Long Island City, Queens. The announcement followed months of intense opposition by activists and local politicians dismayed that Amazon would receive up to $2.5 billion in tax subsidies to—as they saw it—accelerate the gentrification of local neighborhoods.

“While polls show that 70% of New Yorkers support our plans and investment,” Amazon sniffed, “a number of state and local politicians have made it clear that they oppose our presence and will not work with us to build the type of relationships that are required to go forward with the project we and many others envisioned in Long Island City.”

Critics such as state Senator Michael Gianaris blasted the statement. “Like a petulant child, Amazon insists on getting its way or takes its ball and leaves,” Gianaris told The New York Times. “The only thing that happened here is that a community that was going to be profoundly affected by their presence started asking questions … Amazon admits they will grow their presence in New York without their promised subsidies. So what was all this really about?”

Securing subsidies was certainly one thing the HQ2 search was about, using the great game to paper over what has become a common tactic—leveraged by corporations from sports teams to Tesla to Foxconn—of playing local regions off one another to secure sweet deals. These economic-development deals have not always gone well. Companies don’t deliver on their promises or change plans. Teams leave. Cities, somehow, are usually left holding the bag, and by bag, I mean debt.

[Read: Amazon’s HQ2 spectacle isn’t just shameful—it should be illegal]

Nonetheless, cities kept doing it, driven by a model that the sociologist Harvey Molotch described as “the city as growth machine.” It’s as if Molotch was describing the actual HQ2 search in his 1976 paper.

“An elite competes with other land-based elites in an effort to have growth-inducing resources invested within its own area as opposed to that of another,” he wrote. “Governmental authority, at the local and nonlocal level, is utilized to assist in achieving this growth at the expense of competing localities.”

As residents of the biggest winners of the city lottery—say, San Francisco, New York, Seattle, Denver, Washington, D.C.—have found, a rich city is great for the rich, but it’s very hard on everyone whose labor is not valued as highly as tech engineers and financiers. The poor are forced to the outer reaches of the metro area, or suffer ever greater alienation from the changing city around them. As the West Oakland activist Brian Beveridge once put it, in a rising tide, “all boats don’t rise, because people don’t have a boat.”

San Francisco now serves as a metaphor for how tech money can transform even one of the most charming and irascible cities into a place where no teachers can afford to live, even young rich people are terrified of losing their apartments, and longtime residents mutter under their breath as they wander through suddenly alien streets.

These cities are the spatial embodiment of the rocketing inequality of the past several decades, which shows that it’s quite easy to grow a city, or a nation, or a global economy while only the very, very, very rich eat up all that income growth.

And what better avatar for this situation than Jeff Bezos, currently the world’s richest man, versus Queens? Deposed Uber CEO Travis Kalanick played a similar role in the company’s canceled new corporate headquarters in uptown Oakland. These guys are bad, opponents said—why are we inviting them into our city? Or as activists put it candidly, in nearly daily graffiti on the in-progress building, “Fuck Uber!”

For decades, cities’ answer to the questions posed about their economic practices has been simply, These projects bring jobs. But urban activists have finally found an opponent that is easier to beat than the Raiders or even a condo builder: the technology industry.

Self-driving cars promise to change cities, mint billionaires, and push robots into the everyday lives of millions of people. The only problem is, no one knows quite when or how. And with all the research and development locked up inside private companies, the public has little information to judge the progress of the technology, aside from the occasional PR reveal or disaster.

We have one (imperfect) yardstick, however: the numbers that the California Department of Motor Vehicles requires that any company testing an autonomous vehicle in the state file every month. Those are rolled up and released in January of each year. Though people in the industry don’t like what they see as the uneven comparisons between companies, this is the best we’ve got. The data include two primary numbers: the number of autonomous miles driven, which gives a rough indication of the scale of a program in the state, and the number of disengagements, or when a human driver takes over for the computer.

For every year of these disclosures, Waymo, the self-driving-car project within Google’s parent company, Alphabet, has been the leader by a wide margin.

The year 2018 was no different. Waymo drove 1.2 million miles in the state, which is not even its primary testing ground. Its cars disengaged 114 times, for a rate of 0.09 disengagements per 1,000 miles. That’s down from 0.18 in 2017. GM Cruise cemented its position as the key challenger to Waymo supremacy, logging nearly 448,000 miles with 162 disengagements, for a rate of 0.19 per 1,000 miles, and that’s on San Francisco’s difficult streets, a fact that GM Cruise’s Kyle Vogt is fond of pointing out. Together, the two companies’ cars drove 86 percent of the autonomous miles in the state.

[Read: Inside Waymo’s secret world for training self-driving cars]

Apple, whose self-driving program is less high-profile, came in at No. 3 in miles driven, with nearly 80,000 autonomous miles. However, the company’s disengagement rate was 871.65 disengagements per 1,000 miles, according to the DMV methodology—the highest of the 27 companies that submitted data.

Apple’s cover letter to the DMV indicates that the company changed its reporting methodology halfway through the year, and that after July 2018, the company’s rate of “important disengagements” would land it in the realm of 0.5 disengagements per 1,000 miles, which would be in the top tier of performances.

That enormous discrepancy highlights what the various companies don’t like about the reporting processes. They don’t have a true standard for what must count as a “disengagement,” leaving room for companies to make their numbers look better (or even worse) than they might otherwise be. Where the miles are driven obviously matters, too: It’s harder to drive in Manhattan than Palo Alto. And these cars are trying to learn, which means you don’t necessarily want to encourage drives on empty highways, where the learning rate per mile is low.

Nonetheless, no other state requires any kind of disclosure about miles driven or disengagements. These numbers are all we have, in large part because none of these companies want to self-report, nor do their interactions with the DMV seem to indicate that they’d like more stringent standards.

Huge, huge, huge money is at stake in the race to build autonomous vehicles of all kinds, and no company wants to give away more secrets than it has to.

This year, the field of real competitors has grown. More companies have attained the basic ability to run a self-driving car on the streets of California for fairly extended periods of time. The most advanced ones have expanded their driving greatly. And it’s worth noting that much of the action occurs in special training facilities outside California (whether that’s in Arizona or the traditional seat of the car industry, Michigan), or in simulated worlds filled with real data.

In just the past week, two new players received $1.4 billion of funding: $940 million to Nuro, a driverless delivery company, and $500 million to Aurora. Amazingly, both companies can trace their lineage to the Google self-driving-car project that eventually spun off into Waymo, a company that financial analysts value at tens of billions of dollars. In 2018, self-driving-car company Zoox also raised $500 million. Many others have secured or are eyeing tens of millions, a hundred million, or even a billion dollars.

Nuro, Aurora, and Zoox all appear on the DMV list. Zoox and Nuro both posted top-five disengagement numbers and ranked fifth and sixth in miles driven (30,000 and 25,000, respectively). Aurora drove almost 33,000 miles (fourth in the pack), but showed a very high disengagement rate of 10.01 per 1,000 miles. That could be consistent with the kind of long-term-oriented program that founder Chris Urmson has outlined.

[Read: All the promises automakers have made about the future of cars]

Nuro’s regulatory filing was also unusually detailed in its description of the problems that its vehicles encountered, making concrete the general problems that self-driving cars can encounter. Among them: Cars can have trouble identifying objects; the mapping information they rely on to function can be out-of-date or inaccurate; they can have problems with their sensor inputs. And they can simply make bad decisions with the information they have; the filing includes entries such as “planned trajectory failed to leave adequate room for parked car on narrow road” and “planned trajectory resulted in erroneous sharp braking, recklessly tailgating motorist may have been unable to stop.”

What about Tesla, which has talked a big self-driving game? Like last year, the company used the necessity of filing a letter with the DMV to lobby for its heterodox mode of self-driving-car development, which included huge numbers of real-world miles logged by human drivers and its Autopilot mode, albeit with a more limited range of sensor data than other self-driving cars. Tesla drivers have logged 1 billion miles in Autopilot mode, according to the company’s filing. If that turns out to be the winning strategy, clearly Tesla will suddenly come into focus as the leader in autonomous driving. But until that day, we don’t really know how far up the ladder toward true autonomy their approach can take them.

The ways in which schools and students think about the possibility of mass violence on campus changed a lot between the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School and the 2018 one at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Dave Cullen’s last book, 2009’s acclaimed nonfiction work Columbine, chronicled the public and private lives of high-school students who survived the 1999 Columbine massacre as they grappled with the question of why this unthinkable horror had happened at their school. Cullen’s newest book, Parkland—about the activism of the survivors of the February 14, 2018, attack that killed 17 students in Parkland, Florida—follows a group of students determined to not let the world forget that of course this horror had happened at their school. Why wouldn’t it have? It was happening everywhere else. These students, unlike those who survived the tragedy at Columbine, grew up under the ever-looming threat of school gun violence, and then it materialized. Still, the Parkland kids’ back-to-school experience looked a lot like the Columbine kids’. They missed their dead classmates; they feared more violence in their classrooms; they had to fight through post-traumatic–stress symptoms to get to calculus on time.

There’s a developing set of protocols for how to handle the process of reintroducing kids to school after a shooting takes place on campus. As I reported last year, there are now “best practices” for how to reopen a school after a shooting, and that’s partly because many administrators at schools where a mass shooting has taken place call the administrators of the school that had the last mass shooting to ask for advice on how to ease kids back into the school setting. It’s one thing to hear about post-shooting protocols from experts, though, and quite another to see them in action through students’ eyes. Parkland, reported over the course of the 10 months after the shooting, mainly focuses on the gun-reform movement that took shape after the Douglas shooting, but it also paints a vivid portrait of what going back to school after a shooting is really like for students.

Douglas students returned to class two weeks after the shooting, on February 28, but on the Sunday prior, the school held an open house. In one of the book’s more heartbreaking scenes, Cullen notes how painful and scary the first reunion between students and their terrorized school can be. The high school that Sunday still felt, in some ways, like a crime scene: Helicopters hovered, capturing video of the school for TV news, and the sound of the chopper triggered anxiety and panic for some of the students who had heard the motors over their school the day of the shooting. One student notes that walking around that day, he and his friends heard a car engine go pop pop pop, “and we all started hyperventilating.”

When classes did resume, though, Cullen describes a school transformed into something more like a rehab center. Classes weren’t really classes at first: “So much Play-Doh, so many comfort dogs,” one student, Daniel Duff, says. (The Play-Doh he found somewhat ridiculous; the comfort dogs he found wonderful.) Another student, Lauren Hogg, describes coming back to school to find “therapists literally everywhere,” even in the school library. Their on-call availability, she says, was immensely helpful for students who were experiencing grief that came in waves, washing over them at unpredictable and sometimes inopportune moments.

[Read: The developing norms for reopening schools after shootings]

The weeks that follow a school shooting, Cullen writes, are shaky. Students’ routines resume, and many find comfort in the returning familiarity and controllability of their days, but many still experience sudden moments of fear, worry, and sadness at school. When Matt Deitsch, the older brother of two of the survivors, tells Cullen about his little sister’s accounts of being at Douglas after the shooting, he says she’s one of many students who get anxious when they use the bathrooms. “She says, ‘Now when I go to the bathroom I think if I take a little longer to wash my hands maybe I’ll survive if it happens again,’ ” Deitsch says. Or sometimes she’ll take the long way back from lunch and wonder if this choice will save her life.

Many of the students Cullen spoke with mention the never-quite-normal presence of empty desks where students killed in the shooting used to sit. One student says sitting next to a slain friend’s empty desk in classes they used to share is “when it hits [him] the worst.” Another finds it haunting that during other periods of the day, “people probably sit there [in the conspicuously empty desk] and they have no idea this desk is the one we all look at in our class.”

Parkland also illustrates all the tiny ways in which the memory of a shooting can find ways to disrupt students’ lives even after their daily schedules and routines have long since picked back up. Before Douglas students performed their much-publicized production of the musical Spring Awakening last May, for example, their theater director had to confront the question of how, or even whether, to portray a fatal gunshot scripted into one of the final scenes. It was necessary to the plot of the show, she told Cullen, but it also seemed like an especially ghastly thing for this particular audience to have to witness. (Ultimately, the directors decided to keep the gun in the scene, but instead of a gunshot sound effect, they simply blacked out the lights.)

Throughout the rest of the school year, Cullen notes, certain events caused the student body’s emotions to flare up again—and they highlight the fact that the school is full of kids who are moving forward at different speeds and in different ways. Hogg, for example, found herself crying at school in April while looking over a special edition of the school paper dedicated to the 17 victims. Other students nearby laughed at her for weeping. Many kids felt bad about enjoying springtime school events such as prom when they knew their dead classmates couldn’t, while others balked at the idea of incorporating a memorial for the shooting victims into their prom event.

“Somebody brought up this idea of having something about the shooting at prom, and we were like, ‘That’s the worst idea you’ve ever come up with!’ ” one student told Cullen. Prom, the student added, needed to be a night when students could feel some modicum of normalcy kicking back in. In the end, prom included a 17-second silent tribute to the victims.

And graduation—“the most conflicted day” of recovery for school-shooting survivors—was a similarly fraught occasion, Cullen writes. To some seniors, it felt like a statement of strength, of fortitude in the face of tragedy. To others, moving forward into their college and adult years without their fallen classmates felt unfair.

Most of how Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School handled the aftermath of the shooting last February, it’s worth noting, tracks closely with what experts consider to be best practices, such as the open-house event before classes resume, the many counselors and therapy dogs stationed all over the building or campus, the slow easing back into academics in the classroom, and the heads-up to teachers that kids will be moody or upset or weeping on particular days for the rest of the school year. Cullen’s Parkland offers a rare and vital glimpse into what all these measures look like in action—and a reminder that no matter how many active-shooter trainings or lockdown drills have been implemented, no matter how many school-reopening protocols are in place, these tragedies cannot be prepared for before they happen or quickly resolved after they do.

It is a very odd thing to think of myself as a school-shooting survivor. The first time I acknowledged that I was a survivor was on October 5, 2018, when I attended an event as a guest of Everytown for Gun Safety. I went over to the Moms Demand Action table to sign up to be a volunteer. As I filled out the form, I stared at the question asking how I was connected to gun violence. I stood there for what felt like an hour. Finally I checked the box to indicate that I was a survivor of gun violence. I had never thought of it that way before.

I wasn’t in Building 12. I didn’t see anyone get shot. I never saw the shooter. I didn’t think of myself as a survivor. When I said that to my husband, he told me that I absolutely was. I was on campus that day. I heard the shots when I got outside after the fire alarm went off. I returned to my classroom, where I kept 15 students safe in my classroom for two and a half to three hours, until the SWAT team entered my room. I might not have seen anything, but I was there and didn’t know whether I’d be next.

I remember the day vividly. It’s the hours, days, and weeks following that are a blur. I went to school the morning of February 14, 2018, to give a quiz to my senior English classes. I joked that I was ruining their Valentine’s Day by giving them the quiz. To make them smile, I put Hershey’s Kisses on their desks. Later that day, 20 minutes before school ended, my world changed forever. I left school shattered, broken, lost.

[Read: The next Parkland could happen anywhere]

On February 15, I did a 12-hour media marathon, appearing on TV stations across the country. It was surreal to stand across the street from my school and talk about an event that had happened less than 24 hours before. In the afternoon, I attended a vigil at Pine Trails Park, a mile north of the school. I saw students who I had seen only the day before, but it felt like a lifetime ago.

On February 16, I attended the funeral for Meadow Pollack, whom I had as a freshman in my English class. That was the first time I cried since leaving the school two days earlier.

On February 17, I met with my yearbook staff. I told them how much I loved them, and how glad I was that they were safe. Several members of the staff not only were in Building 12, but were in the classrooms the shooter turned his gun on. They watched their friends and classmates die. They were injured. If the shooting had happened one day later, it would have taken place during yearbook class. I couldn’t wrap my head around how many of them could have been traveling around the building getting quotes, or taking pictures. The thought that I could have lost anyone was too much to take. I began to cry. They cried too.

On February 18, I attended the funeral for Jaime Guttenberg, who was in my Journalism 1 class that year.

After that, I don’t know what I did most days. I just know that I tried to keep myself busy.

On February 23, I went back to school for the first time. I entered my classroom, and it looked like a freeze frame of the moment before the shooting, like time had stood still. The date February 14 was still on the board; the quizzes were still on the desks; students’ phones were still plugged in; the computers were still on. I began to have an anxiety attack and couldn’t breathe. I had to get out of there. I was in the room for a total of five minutes.

When school resumed on February 28, I hugged each one of my students. I told them that I would always be there for them. Within the next few weeks, my students started opening up about what they had experienced. I never prompted them. I always listened. It broke my heart that these things had happened at all, but especially to children—because that’s what they are.

In the months that followed, we put together a yearbook like no other; one that was perfect, that honored the victims. We added pages for profiles of those we had lost, and yet more pages to cover what happened that day and in the weeks after. I edited and published a book, Parkland Speaks, that features Parkland students’ writing about that day. I have worked hard to take care of myself. I see a psychologist weekly. I also spent much of 2018 planning my son’s bar mitzvah, which was last month. That would have stressed me out in a different period of my life, but it turned out to be a nice diversion from the stress and pain that permeated every other second. It was nice to make sure he felt special and to not focus so much on myself. Perhaps this was my way of putting off the feelings I knew I’d have as February 14 drew close again, but I was okay with that.

Moving forward, I plan to take things one day at a time. That’s really all I can do. I’m a survivor, after all.

Donald Trump has again folded in his negotiations with congressional Democrats—accepting a second budget deal that includes nothing close to the $5.7 billion in funding for a border wall that he demanded. This outcome was entirely predictable. The sequence of events that led here has occurred again and again when Trump negotiates. Think of it as a play in four acts.

Act I: Trump Invents a Crisis

Since entering the presidential race, Trump has relentlessly described unauthorized immigration—which has been decreasing—as a national emergency. In the final days before last November’s elections, he returned to that theme with a vengeance. In a November 1 speech from the Roosevelt Room, he offered “an update to the American people regarding the crisis on our southern border—and crisis it is.” Later in the speech, he called it “an invasion.”

He’s employed similar hyperbole on trade. During the campaign, Trump called NAFTA “the single worst trade deal ever approved in this country” (a statement with which, Politifact noted, “few [experts] agree.”) He was still at it last August, when he declared, “We lost thousands of factories and millions of jobs because of NAFTA” (a statement The Washington Post gave three Pinocchios).

[Read: Why Trump keeps creating crises]

Trump also invented a crisis with North Korea. Rather than see Pyongyang’s nuclear program for what it was—an effort at deterring an American invasion—Trump in his first year as president described it as an immediate threat. And rather than contain North Korea’s nuclear program via diplomacy—as Bill Clinton’s administration did fairly successfully in the 1990s—Trump described negotiations as a waste of time. “Being nice to Rocket Man hasn’t worked in 25 years,” he announced in October 2017. “Why would it work now?”

Act II: Trump Creates a Crisis

Having described an imaginary crisis, Trump—in all three cases—created a real one. To combat the supposed emergency at the border, he demanded billions for a wall and thus provoked the longest government shutdown in American history. To remedy the supposed catastrophe of NAFTA, he imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from Canada and Mexico (among other countries), which prompted Ottawa and Mexico City to retaliate with tariffs of their own, thus plunging America’s relations with its neighbors down to their lowest level in decades. And to protect the United States from the supposedly imminent threat of a North Korean missile strike, Trump repeatedly threatened war—and, according to Bob Woodward’s book, Fear, came close to actually starting one.

Act III: Trump Folds

As the crises took shape, it became clear that Trump lacked the power to achieve his stated goals. Congressional Democrats—buoyed by polls showing that most Americans blamed Trump for the shutdown—held firm against a border wall. The governments of Canada and Mexico—buoyed by public revulsion against Trump’s bullying—held firm in trade negotiations. And Trump’s military advisers warned him that he couldn’t launch a preventive military strike on North Korea without incurring hideous costs.

[Read: Trump was always going to fold on the border wall]

So in all three cases, Trump ended up accepting deals that were little better—if not worse—than the ones he had derided in Act I. He inked a new trade agreement with Canada and Mexico that, according to Politifact, constituted “mostly a symbolic shift” away from NAFTA. (Congress has yet to ratify it.) He signed a nuclear deal that secured fewer concessions from Pyongyang than the previous agreements Trump had scorned. And this week, he accepted a budget deal that includes less money for the border wall than the one he spurned last December.

Act IV: Trump Claims Victory

Having failed to achieve his goals, Trump returns to the deception of Act I, but with a twist. Instead of pretending there is a crisis, he pretends the crisis has been solved. While most experts noted that Trump’s successor to NAFTA—the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA)—wasn’t much different, Trump called it a “model agreement that changes the trade landscape forever.” Although Kim Jong Un provided no concrete guarantees of denuclearization in his summit with Trump last year in Singapore, Trump tweeted that the “problem is largely solved” and “there is no longer a Nuclear Threat from North Korea.” And although not one inch of new border wall has been built since Trump took office, he now justifies his shutdown gambit by claiming that the border wall is almost complete. During Trump’s speech this week in El Paso, Texas, when the crowd chanted “Build the wall,” he replied, “You really mean finish that wall, because we’ve built a lot of it.”

[Read: Trump’s NAFTA strategy: bluff, rebrand, declare victory]

Act V? Back to the Beginning

What remains unclear, in all three cases, is whether the show stops at Act IV. Can Trump sustain the fiction that he’s won a glorious victory, or does reality intrude, thus starting the cycle all over again?

Last November, The New York Times published a remarkable front-page story entitled, “In North Korea, Missile Bases Suggest a Great Deception.” At first glance, the headline implied that North Korea was deceiving the United States government about its ongoing nuclear efforts. But the text of the article suggested that the actual deception was quite different. The authors reported that “North Korea is moving ahead with its ballistic missile program at 16 hidden bases that have been identified in new commercial satellite images, a network long known to American intelligence agencies but left undiscussed as President Trump claims to have neutralized the North’s nuclear threat.” In other words, North Korea wasn’t deceiving American intelligence.

One interpretation of the Times article is that Trump was deliberately deceiving the American people so as not to puncture the illusion that he had successfully “neutralized the North’s nuclear threat.” But it’s also possible that the intelligence agencies deceived Trump, withholding evidence for fear that, were Trump forced to acknowledge that his apparent triumph had been a sham, he would take America back to the brink of war.

The question is whether, when Trump declares victory, he’s merely pretending to have won, or actually believes it. As bad as it would be for a president to deliberately and repeatedly lie to the public, it might be worse for a president to deliberately and repeatedly lie to himself. If Trump wakes up one morning and realizes that, despite the USMCA, American manufacturers are still relocating to Mexico, he might tear up the agreement and provoke a new trade war. The more Trump is forced to admit that his border wall isn’t actually being built, the more likely he is to declare a national emergency, thus creating a legal and even constitutional crisis.

Preventing the cycle from starting all over again might require allowing Trump to maintain his delusions of grandeur. It’s like dealing with small children: It’s safer to let them think they’ve won than endure the temper tantrum that will ensue if they realize they’ve lost. As dangerous as Trump is when he lies, he might be even more dangerous when forced to temporarily admit the truth.

After this week’s CNN town hall, it’s more and more clear that any money Howard Schultz might spend on an independent presidential bid would function as an in-kind campaign contribution to Donald Trump.

Schultz offered few policy specifics during the hour-long session Tuesday night and repeatedly retreated to platitudes when pressed to clarify his position on core issues, including taxes and health care. But to the extent that Schultz did explain his views, they stamped him as a moderate Democrat, tilting toward the party’s center on economics while firmly identifying with its solidifying liberal lean on social and racial issues.

It’s hard to imagine that the mix of perspectives Schultz presented—from opposition to a border wall to support for new limits on gun ownership—will ultimately attract many voters drawn to Trump’s hard-edged racial nationalism. That means that if Schultz runs and his views become better known, he’s likely to draw mostly from the pool of voters discontented with Trump, not the president’s previous supporters.

Though Schultz repeated again Tuesday that he doesn’t intend to do anything to help Trump get reelected, almost everything else he said underscored the likelihood that he would do exactly that. “The fact that he’s doing this is potentially catastrophic,” says Matt Bennett, the executive vice president for public affairs at the centrist Democratic group Third Way. “Republicans are very unlikely to vote for him in this tribal moment. The only votes he would get would come at the expense of our nominee. And if he peels away some Democrats and independents, he could reelect Trump.”

[David Frum: Howard Schultz may save the Democratic Party from itself]

Schultz, who described himself as a “lifelong Democrat” before exploring this independent candidacy, has quickly endorsed an array of positions that distance him from the vast majority of Republican-leaning voters, especially those enthusiastic about Trump.

On Tuesday, Schultz embraced legal status not only for Dreamers, the young people brought to the country illegally by their parents, but for all the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. And he dismissed Trump’s signature call for a border wall.

On guns, Schultz clearly affirmed his support for banning assault-style weapons. “I have a hard time understanding why people need to carry an AR-15 around in the streets of where they live,” he said. In a speech at Purdue University last week, he’d previously endorsed “universal and enhanced background checks with no loopholes.”

On climate change, his concern is “at the highest level” and dealing with it “would be a top priority” for him as president, Schultz told a questioner Tuesday. And while he steadfastly resisted specifics, Schultz did clearly say that he would seek to raise taxes on the wealthy and roll back at least part of the GOP’s huge tax cut for corporations. He denounced the Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, and took a “Mend it, don’t end it” approach to next steps: “Now we got to go back in and fix the Affordable Care Act.”

And he clearly signaled sympathy for those arguing that the nation must do more to expunge systemic racism and discrimination, saying Americans must recognize “unconscious bias” and expose themselves to “uncomfortable conversations.”

That isn’t exactly a catalog of positions designed to drive wedges in Trump’s coalition. Take the border wall: Just 5 percent of voters who approve of Trump’s job performance said they disapproved of the wall in the latest CNN survey. That compares with 90 percent opposition to the wall among voters who disapprove of Trump.