On October 2, Jamal Khashoggi walked into Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul and was not seen publicly again. One month later, the Saudi journalist’s fate has been pieced together incrementally, through media leaks, Turkish official statements, and (oft-changing) Saudi government admissions.

We still don’t know much about what happened to Khashoggi. “In a way,” Neil Quilliam, a Middle East expert at Chatham House, told me, “it’s almost easier to say what we do know, because there are so few things.”

The vast majority of what is known about what allegedly happened to Khashoggi has come via unofficial channels—namely, through a series of leaks from Turkish sources to media outlets. The first such leak, alleging Khashoggi’s death, emerged days after he disappeared. Others soon followed, involving reports of a Saudi hit squad, gruesome audiotapes, and a Khashoggi decoy.

[Read: Turkey is treating the Khashoggi affair like it’s must-see TV]

Here’s a rundown of what the officials have said, what leaks have revealed, and what remains unknown.

What Officials Have Said

Turkish security footage shows Khashoggi entering the Saudi consulate on the afternoon of October 2, where his fiancée, Hatice Cengiz, said he went to obtain paperwork for them to marry. Turkish authorities said that a group of 15 Saudi nationals then strangled Khashoggi at the consulate as part of a “planned operation,” which ended with his body being “dismembered and destroyed.”

Saudi Arabia’s account, which has undergone a series of revisions, offers a somewhat different story. Riyadh now says that Khashoggi was killed in the consulate as part of a “premeditated” attack, but the kingdom claims it was a “rogue operation” by members of the Saudi intelligence service. Riyadh said that it has fired five top officials and arrested 18 others for the murder, and has insisted that the royal family, including Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, was not involved.

What Leaks Have Revealed

Unnamed Turkish officials told the media that audio recordings of Khashoggi’s interrogation and murder exist, capturing gruesome details about the duration of his detention and torture. The Turkish government hasn’t publicly released any such recordings, though it has been reported that CIA Director Gina Haspel heard the audio during her visit to Turkey last week.

A senior Turkish official told CNN that a Saudi national posing as Khashoggi was dispatched around Istanbul just hours after Khashoggi entered the consulate, in an apparent attempt to cover up his disappearance. The individual was captured on Turkish surveillance footage wearing glasses, a fake beard, and clothes identical to those worn by Khashoggi that day.

An unnamed Saudi official told Reuters that Khashoggi’s killers removed the body from the consulate by rolling it up in a rug and giving it to a “local cooperator” for disposal.

What We Don’t Know

Three main questions remain regarding what happened to Khashoggi. First, the whereabouts of his body are unknown.

Second, we don’t know who gave the order for Khashoggi to be killed. Was it a rogue operation, as the Saudis claim? Or did Mohammed bin Salman, the country’s de facto leader, play a role?

The answer to the second question will have profound implications for the third: What impact, if any, will Khashoggi’s death have on Saudi Arabia’s global standing? A number of its allies chose to boycott last month’s investment conference in Riyadh and suspended political visits to the kingdom. Some, including Germany and Austria, have called for halting Saudi arm sales. Others, such as the U.S. and France, have ruled this response out entirely.

Speaking at a memorial in London this week, Cengiz urged President Donald Trump and other world leaders not to assist in a “cover up” of what happened to her fiancée. “I want justice to be served,” she said. “Not only for those who murdered my beloved Jamal, but for those who organized it and gave the order for it.”

Though Saudi Arabia and Turkey are conducting a joint investigation into Khashoggi’s death, it’s unlikely to yield definitive answers about what happened to him, nor will it necessarily result in a prosecution. Saudi Arabia has already rejected Turkish demands that the suspects be extradited to Ankara for trial.

“There is a forming narrative that is being shaped between Turkey and Saudi Arabia, and that’s symptomatic of them trying to come to some kind of agreement,” Quilliam said. “I don’t think we’re ever going to find out the definitive truth. It will be a sort of negotiated truth that both sides can sign up to.”

Hard-liners: President Donald Trump is looking to electrify his base with renewed anti-immigration fervor, releasing a racist ad on Thursday via Twitter and gesturing at an executive order on immigration to come next week. The GOP might need more than base voters to retain political control, though. What’s the long game of the close Trump adviser who’s at the root of some of this hard-line strategy? For those counting down: Five days to the U.S. midterm elections.

Fight for the Right: A consequential legal fight over voting rights is brewing in this tiny, predominantly white Texas county, where students at the historically black public university Prairie View A&M have alleged that the county’s early-voting plan uniquely restricts their options. The battle over voting rights here goes way back.

Give Me Space: There’s a big black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, with the weight of several million suns. Thanks to telescope data and some animation work, we can see what material getting sucked into a black hole might look like. Also: Do you give public transit a wide berth because you’re afraid of getting sick? Or do you think riding public transit has built up your general resistance to illness? Heading into flu season, here’s some real talk.

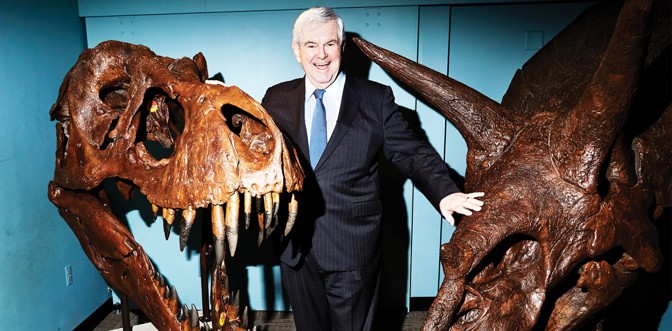

Snapshot “Few figures in modern history have done more than Gingrich to lay the groundwork for Trump’s rise,” McKay Coppins writes in this profile of the former speaker of the House, photographed above by Amy Lombard. “During his two decades in Congress, he pioneered a style of partisan combat—replete with name-calling, conspiracy theories, and strategic obstructionism—that poisoned America’s political culture and plunged Washington into permanent dysfunction.”Evening Read

“Few figures in modern history have done more than Gingrich to lay the groundwork for Trump’s rise,” McKay Coppins writes in this profile of the former speaker of the House, photographed above by Amy Lombard. “During his two decades in Congress, he pioneered a style of partisan combat—replete with name-calling, conspiracy theories, and strategic obstructionism—that poisoned America’s political culture and plunged Washington into permanent dysfunction.”Evening ReadIn weighing the costs and benefits—and respective contributions to gridlock—of buses with fixed routes versus ride-shares like Uber and Lyft, Jarrett Walker comes down on the side of buses.

When you drive alone (or take Uber alone) in a gridlocked street or freeway, you are taking more than your fair share of the limited space. When stuck in traffic, you are blocking others from moving freely.

If cities want to move people faster than walking while allowing them to take up only their fair share of space, two options arise. One is to use a vehicle that’s not much bigger than the human body, such as bicycles and scooters. Those tools work well for certain people in particular circumstances, but not for everyone. The other option is to share the ride in a vehicle. If space is really scarce, that vehicle will have to carry lots of people. In most cases, riders will have to share a vehicle with strangers, people who are not traveling for the same purposes or even to the same places. That’s what public transit is.

Fixed public transit deploys large vehicles flowing along a set path, and riders gathering at stops to use them. That way, the vehicles can follow a fairly straight line, and they don’t need to stop once for every customer. That is what makes them worth walking to get to. It is one of the best ideas in the history of transportation.

And walking is key to it.

Let’s not reinvent the wheel—or public transit, Walker argues.

What Do You Know … About Global Affairs?1. Which of the following countries offer automatic citizenship to babies born within their borders? Canada, Germany, Mexico, the United Kingdom.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. High tides and strong winds brought unprecedented flooding of up to five feet in this Italian city in the past few days.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. The controversial Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., recently confirmed what scholars had long suspected: Artifacts it had been displaying as authentic fragments of the __________________ are likely forgeries.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: CanadA; Mexico / venice / Dead sea scrolls

Urban DevelopmentsOur partner site CityLab explores the cities of the future and investigates the biggest ideas and issues facing city dwellers around the world. Gracie McKenzie shares today’s top stories:

Gerrymandering! Urban-rural divides! Nativists! Feminists! This deliciously wonky interactive map of House election results since 1840 has it all.

In the world of trap music, Ko Wen-je is an unlikely newcomer. And yet here we are: The mayor of Taipei, Taiwan, just dropped his first music video, “Do Things Right.”

“You can track Washington’s development through this narrow lens of tunnels. The emergence of industrial technology, the push in the 19th century for sanitation, the mid-century interest in mass transit—it’s all there.” This interactive history of underground D.C. reveals the quirks of the city.

For more updates like these from the urban world, subscribe to CityLab’s Daily newsletter.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Atlantic Daily, and we welcome your thoughts as we work to make a better newsletter for you.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

In an address from the Roosevelt Room Thursday, President Donald Trump criticized the nation’s immigration laws, decried the Central American migrant caravan moving through Mexico, and announced that he’s “finalizing a plan” that would limit who could claim asylum.

“Migrants will have to present themselves lawfully at a port of entry,” Trump said. “Those who choose to break our laws and enter illegally will no longer be able to use meritless claims to gain entry into our country.”

The plan—which Trump suggested could come via an executive order next week—would likely face immediate legal challenges: U.S. and international law state that migrants have the right to apply for asylum once on U.S. soil. Trump’s address on Thursday fell short of describing how he’d circumvent those laws; nor did the president detail any other major policy changes. Instead, his remarks seemed designed to keep the spotlight on immigration, the issue he’s betting the midterms on.

Trump has escalated his attacks against Central American migrants in the final days of the campaign, dubbing the caravan an “invasion,” releasing a racist ad, and calling into question reports that those traveling have valid asylum claims.

Despite the president’s urgent tone, the migrant caravan is still about 1,000 miles away. And the majority of its members—estimated to be around 4,000 people, with other, smaller groups following behind—are reported to be women and children. Many are expected to present themselves to authorities to claim asylum, not evade capture.

Trump spent much of his address condemning “catch and release,” the practice of letting immigrants who’ve claimed asylum into the United States while they await asylum proceedings, so long as they’ve demonstrated a “credible fear” of returning to their home countries.

Trump said that migrants will no longer be released after being apprehended, but it’s unclear whether his edict has the force of policy. He didn’t explain how his administration would follow through beyond mounting tents. “We have thousands of tents. We have a lot of tents. We have a lot of everything. We are going to hold them right there,” he said. He falsely claimed that immigrants purposefully miss their scheduled court hearings after being released. According to a study by the American Immigration Council, over a 15-year period, 96 percent of asylum-seeking families went to their immigration-court hearings.

Trump’s address was preceded by a press release from the Department of Homeland Security that condemned “catch and release loopholes,” referring to existing asylum laws and the Flores Settlement Agreement, which places a limit on how long children can be held in immigration detention. The department cited these so-called loopholes as a reason for “a dramatic transformation in the population of those seeking to enter our country illegally.”

Indeed, there have been shifts in the migrant population: In fiscal-year 2018, 56 percent of the people apprehended at the southern border were from Central America, according to DHS data. In 2010, it was 10 percent. Deteriorating conditions in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala have contributed to the uptick of migrants journeying to the U.S.-Mexico border from the region.

Trump’s address Thursday was the latest in a broad administration effort to limit asylum. Earlier this year, Attorney General Jeff Sessions drastically narrowed what the government considers grounds for asylum, barring victims of domestic abuse and gang violence from accessing the protections. “Asylum was never meant to alleviate all problems—even all serious problems—that people face every day all over the world,” he said in a June speech.

His remarks also came on the heels of the deployment of thousands of active-duty National Guard troops to the U.S.-Mexico border. Trump has repeatedly cited the military’s presence as a warning to those journeying to the border, prompting questions about whether troops are being used as a political tool ahead of next week’s elections, something Defense Secretary James Mattis denies.

Trump proclaimed Thursday that the number of troops could reach 15,000, far outnumbering the number of migrants expected to arrive. “We have already dispatched for the border the United States military, and they will do the job,” Trump said. “They are setting up right now and they are preparing. We hope nothing happens but if it does, we are totally prepared, greatest military anywhere in the world.”

What Trump doesn’t say is that the military is limited in what it can do on U.S. soil. Their time at the border will largely be spent assisting Customs and Border Patrol. This isn’t the first time troops have been deployed. Previous administrations have also sent them: Former President Barack Obama, for example, sent up to 1,200 Guard members to address drug and human trafficking. But in Trump’s mind, it may just be the show of force that counts. As my colleague David Graham reported earlier today, Trump appears to be doing everything he can to ensure his base turns out next Tuesday. His immigration address is yet another example of that effort.

Written by Elaine Godfrey (@elainejgodfrey), Madeleine Carlisle (@maddiecarlisle2), and Olivia Paschal (@oliviacpaschal)

Today in 5 LinesIn a speech from the White House, President Trump announced that he will issue an executive order next week on immigration, and accused asylum seekers of making a “mockery” of immigration laws.

In a last-minute effort to turn out his base ahead of the midterms, Trump released a race-baiting ad about immigrants and crime.

Robert Bowers, the suspect in Saturday’s mass shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue, pleaded not guilty to all 44 counts against him and requested a jury trial.

Billionaire Oprah Winfrey campaigned in support of Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams in Marietta, Georgia, but swatted down rumors of a 2020 presidential run.

In an interview, U.S. Ambassador to Russia Jon Huntsman said he has Stage 1 cancer.

Today on The AtlanticThe President’s Closing Argument: In the final week before the midterm elections, Trump has warned of an immigrant “invasion” and released a racist ad. To understand this thinking, you have to understand the mind of a close adviser, Stephen Miller. (McKay Coppins)

Tolkien Knew About Power: What can The Lord of the Rings teach us about the Trump moment? “The height of wisdom is to fear [one’s] own drive for power,” writes Eliot A. Cohen.

A History of Voter Suppression: At one historically black public university in Waller County, Texas, black students fought tooth and nail for the right to vote throughout the 1970s. Now, students there allege they’re facing voter suppression again. (Vann R. Newkirk II and Adam Harris)

An Endangered Species: Ideologically moderate candidates are increasingly rare. However, these middle-of-the-road candidates still think they have a place in Congress. (Elaina Plott)

The Rise of Cyberterrorism: Experts have warned about the threat of a major cyberattack for years. Why hasn’t there been one yet? (Kathy Gilsinan)

Snapshot Oprah Winfrey takes part in a town hall meeting with Georgia Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams ahead of the midterm election in Marietta, Georgia. (Chris Aluka Berry / Reuters)What We’re Reading

Oprah Winfrey takes part in a town hall meeting with Georgia Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams ahead of the midterm election in Marietta, Georgia. (Chris Aluka Berry / Reuters)What We’re ReadingWhy So Confident?: Democratic party leaders seem sure that they’ll win the House, even though polls are tightening. Jessica Taylor explains why. (NPR)

A Real Let Down: President Trump has identified himself as a nationalist, but his first term in office has been disappointing for those who adhere to one specific meaning of the label, writes Michael Brendan Dougherty. (National Review)

The Upsetter, Upset: Tea Party conservative Dave Brat shocked the country when he upset House Majority Leader Eric Cantor four years ago in Virginia’s Seventh Congressional District. This year, he’s in the fight of his political life. (Tara Golshan, Vox)

Helping Himself Out: Some voters are calling Kansas’s new voter-ID law “a modern-day poll tax”—one that could help the man who created it, Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, become governor. (Ari Berman, Mother Jones)

VisualizedFrom Abortion to Marijuana: Voters in 37 states will face 155 ballot questions on November 6. Here are some of them. (Kate Rabinowitz, The Washington Post)

Google employees around the globe walked out of their offices today to protest the way the company deals with sexual harassment. It was a well-meaning, but ultimately empty endeavor.

The walkout, which took place at 11 a.m. in all time zones, was prompted by a New York Times investigation last month that alleged that the company had mishandled sexual harassment for years to protect key executives. Google said that it has fired 48 employees for sexual harassment over the past two years.

But many of Google’s more than 85,000 employees want the company to do a lot more. One woman held a poster saying “What do I do at Google? I work hard every day so the company can afford $90,000,000 payouts to execs who sexually harass my coworkers.” Others held signs saying “Time’s up tech,” “Workers’ rights are women’s rights,” and “Not OK Google.” In Mountain View, California, more than 1,000 employees left their desks, according to CNN. In New York, walkout co-organizer Meredith Whittaker addressed the crowd via megaphone. “This is a movement,” she declared to cheers. “I’m here because what you read in the New York Times is a small sampling of the thousands of stories we all have ... the thousands of instances of abuse of power, discrimination, and harassment, and a pattern of unethical and thoughtless decision making that has marked this company for the last year ... This is it; time is up, and we’re just getting started.” The crowd subsequently broke into cheers of “Time is up.”

The first of many coordinated #GoogleWalkout protests has begun - this is at the firm’s office in Singapore. (Pic via https://t.co/h44RZYGGHV ) pic.twitter.com/QeFgmPbHnN

— Dave Lee (@DaveLeeBBC) November 1, 2018In a Thursday op-ed in The Cut, the walkout’s organizers outlined their demands: “All employees and contract workers across the company deserve to be safe ... We demand an end to the sexual harassment, discrimination, and the systemic racism that fuel this destructive culture,” they wrote.

The group and its supporters are advocating for five key changes. They want an end to forced arbitration in cases of harassment and discrimination; a commitment to end pay and opportunity inequity; a publicly disclosed sexual-harassment transparency report; a clear, uniform, and globally inclusive process for reporting sexual misconduct safely and anonymously; and promotion of the chief diversity officer to answer directly to the CEO and make recommendations directly to the board of directors, along with the appointment of an employee representative to the board.

[Read: How women are harassed out of science]

Sundar Pichai, Google’s CEO, sanctioned the walkout. In an email to employees on Tuesday, he wrote, “I understand the anger and disappointment that many of you feel. I feel it as well, and I am fully committed to making progress on an issue that has persisted for far too long in our society ... and, yes, here at Google, too ... In the meantime, Eileen [Naughton, the vice president of people operations] will make sure managers are aware of the activities planned for Thursday and that you have the support you need.”

We, Google employees and contractors, will walkout on November 1 at 11:10am to demand these five real changes. #googlewalkout pic.twitter.com/amgTxK3IYw

— Google Walkout For Real Change (@GoogleWalkout) November 1, 2018Of course, not allowing the walkout would have only further sullied the company’s reputation, and taking a public stance against sexual harassment in a post #MeToo era is hardly revolutionary. If the company truly wants to address deeper issues of sexism and harassment, meeting the organizers’ list of demands would be a start. And if employees want to force the company’s hand, they need to go further than a company-sanctioned symbolic walkout.

Just weeks ago, Google was forced to drop out of the running for a $10 billion cloud-computing contract with the Pentagon after internal revolt. In August, employees also protested after it was revealed that Google was developing a censored search engine for China. In a letter speaking out against the proposed partnership, Google employees declared, “We urgently need more transparency, a seat at the table.”

Not ok, Google. Sign making is underway in NYC! #GoogleWalkout pic.twitter.com/hMLKL0LHOz

— Google Walkout For Real Change (@GoogleWalkout) November 1, 2018Despite the fact that executives have repeatedly pledged to “do more” to work toward diversity, Google’s 2018 diversity report shows that the company is still overwhelmingly white and male. Without aggressive work from senior leaders, the corporate environment is unlikely to change. It’s telling that five out of the six organizers of today’s walkout were women and that the walkout originally began as a 200-person “women’s march.”

Mary Rinaldi, the founder of the Women’s Holding Company, a company aimed at helping female workers get legal advice, said that the PR attention the walkout received is a good thing, if interest can be sustained. “The #MeToo movement has uncovered all these things that have been happening in the shadows. It’s new for society to start accepting that this happens all the time; these aren’t one-off situations. The next step is to keep in the spotlight,” she said.

Risa B. Heller, a crisis-communication expert, is also optimistic about the walkout’s capacity to effect change. “These companies want to be a place where people want to work. They want people to be proud of working for them,” she said. “These kinds of actions certainly make the executives pay attention.”

But while a walkout may be a PR win, it isn’t really affecting Google’s business very much. “So far, #MeToo hasn’t really changed anything in the legal realm of many businesses. While we’ve gotten rid of a lot of terrible men, it hasn’t changed anything structurally,” said Ashish Prashar, a crisis-communication expert with experience in politics.

The Google walkout, in particular, has done a great job of raising awareness of company wrongdoings, but at the end of the day, Google is a for-profit corporation. The way to negotiate with a for-profit corporation isn’t through symbolism, but by jeopardizing profits.

“If women and men and anyone who supports these efforts had an actual strike, then you’d see lasting change,” Prashar said. “They need to say we’re not going to work unless these things actually change.” He also doesn’t see lasting changes coming from Google itself, or any other for-profit tech company for that matter. “It would be brilliant for businesses to do this [protect workers from sexual harassment and punish abusers], but to create a countrywide change, it’s going to require state and federal government to come in and change the laws too.”

As the costumes are put away, the decorations taken down, and candy wrappers gathered from every corner of the house, I thought it would be fun to take one last look at this year’s fun and creepy Halloween celebrations, with photographs from Canada, Turkey, the United States, China, Japan, Chile, England, Poland, and more. It’s only a matter of days before Christmas music will start to fill every public space.

With a few days left before the election, there’s an aroma of panic emanating from the White House. President Donald Trump appears to be trying everything he can to seize control of the news cycle and appeal to base voters with strident, xenophobic rhetoric.

That includes, on Thursday alone, the release of a race-baiting ad about immigrants and crime, and a scheduled speech at the White House in the afternoon, where Trump will reportedly discuss asylum for immigrants. Many members of a caravan working its way slowly toward the United States, and still hundreds of miles away, say they hope to apply for asylum.

The political play here is relatively simple to understand. As my colleague McKay Coppins writes, immigration hard-liners such as the White House senior adviser Stephen Miller see it not only as a midterm talking point, but also as part of a longer cultural battle. Predicting the results of the longer fight is a fool’s errand, but there are at least some reasons to believe that it might not be a perfectly potent technique for the midterms.

[Read: Trump’s closing argument for the midterms is dark and angry].

The ad has drawn immediate comparisons to the infamous “Willie Horton” spot that Republicans used to attack the Democrat Michael Dukakis in the 1988 election, though as the Princeton historian Kevin Kruse notes, it’s actually worse: The makers of the Horton ad were at least ashamed of inflaming racial tension, while the president is proudly trumpeting his. (It’s also not running on television anywhere. Instead, the Trump team is relying on word of mouth and media coverage to spread it, so that even writing critically turns critics into abettors.)

Fearmongering on immigration harks back, as I wrote last week, to Trump’s 2016 presidential run, in which immigration fears were central to his approach, beginning with the campaign kickoff, where he said, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best … They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

That was a highly effective strategy for winning over the Republican base, as demonstrated by Trump’s demolition of the rest of the GOP primary field. But it’s not clear that it’s a great strategy for the electorate as a whole. As The Washington Post’s Dave Weigel notes, immigration was a small part of Trump’s closing argument in November 2016, and perhaps not the decisive one.

After all, Trump had beaten the immigration drum throughout the campaign, and by mid-October, he seemed headed for a defeat in the election. His campaign was reeling from the Access Hollywood tape, but he’d also never been leading. Even his top advisers—even Trump himself—expected him to lose. Then came James Comey’s October 28 letter announcing the reopening of the FBI probe into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server. As FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver and others have concluded, that letter likely lost the election for Clinton. Or, put another way, that letter—and not immigration rhetoric—won the election for Trump.

There’s not a great deal of public polling on Trump and the caravan specifically, but strong majorities consistently disapprove of the president’s handling of immigration, suggesting the issue isn’t a winner for him, even though some of those Americans might feel he’s not going far enough. Meanwhile, polling consistently finds strong support for more dovish immigration policies than Trump’s, including a path to citizenship for recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. His hammering on immigration could also inflame Democrats, pushing more of them to the polls.

It seems just as likely that Trump is resorting to immigration at this stage because, even though the economy is strong, his signature policies, like a big tax cut, aren’t popular; because his health-care position is downright unpopular; and because, without Hillary Clinton in the mix, he doesn’t have an effective villain against whom he can campaign.

Just because it’s a desperation play doesn’t mean it won’t work. But if it does, it will do so not by persuading swing voters, but by driving as many Trump-supporting voters to the polls as possible, and neutralizing Democratic advantages on enthusiasm and turnout. The problem is that while Trump’s base remains devoted, it’s also slowly shrinking. Along with others, I have argued for months that Trump’s strategy of only appealing to his hardest-core supporters and not making any effort to expand his coalition is a dangerous strategy, since his base remains a small share of the electorate. The president’s decision to go all in on immigration in the last week of the midterms will provide a crucial test of whether the base is indeed insufficient—or whether he once more knows something the political class doesn’t.

Even as college students on the whole began to shun humanities majors over the past decade in favor of vocational majors in business and health, there was one group of holdouts: undergraduates at elite colleges and universities. That’s not the case anymore, and as a result, many colleges have become cheerleaders for their own humanities programs, launching promotional campaigns to make them more appealing to students.

As Benjamin Schmidt wrote in The Atlantic recently, humanities majors—which traditionally made up one-third of all degrees awarded at top liberal-arts colleges as recently as 2011—have fallen to well under a quarter. Meanwhile, at elite research universities the share of humanities degrees has dropped from 17 percent a decade ago to just 11 percent today.

[Read: The humanities are in crisis.]

“This wasn’t a gradual decline; it was more like a tidal wave,” says Brian C. Rosenberg, the president of Macalester College. The Minnesota campus, which is well known for its international-studies program, has “never been a science-first liberal-arts college,” Rosenberg said. But now 41 percent of its graduates complete a major in a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) field. That’s up from 27 percent only a decade ago.

The reasons for this national shift are many, but most academics attribute it mostly to the lingering effects of the Great Recession. One of the earliest memories for the generation entering college right now is of Americans losing their jobs and sometimes their homes. Financial security still weighs heavily on the minds of these students. Indeed, a long-running annual survey taken of new college freshman has found in the past decade that the No. 1 reason students say they go to college is to get a better job; for the 20 years before the recession hit in 2008, the top reason was to learn about things that interested them.

Unlike automakers, which can swiftly switch production lines when consumers start buying SUVs instead of sedans, colleges can’t adjust their faculty ranks as quickly in response to public demand. Often, schools wait for professors to retire to reassign those openings to disciplines with the greatest need. Even then, small schools might only recruit a handful of new faculty every year. When they hire, most colleges also need to keep a balance of professors across departments to teach introductory classes that are part of a core curriculum. Macalester, for instance, hired 11 full-time faculty members this year—four of them in computer science and statistics. “We have vacant positions in history and English, and we decided not to fill them,” Rosenberg says.

[Read: What can you do with a humanities Ph.D., anyway?]

With that pace of hiring, it’s nearly impossible for many colleges to keep up with increasing enrollments in popular majors while maintaining small classes. What’s more, faculty members hired for tenure-track positions who eventually earn tenure are essentially promised lifetime employment at the college. “When you put labor in position for 30 years, your ability to respond to future trends becomes really challenging,” says Raynard Kington, the president of Grinnell College, in Iowa. Grinnell expects 70 students to graduate with computer-science degrees this spring out of a class of around 400; four years ago, it graduated just 15 computer-science majors.

To avoid further slippage in humanities majors, elite colleges and universities have resorted to an all-out campaign to convince students that such degrees aren’t just tickets to jobs as bartenders and Starbucks baristas. Colleges are starting early with that push. Stanford University writes letters and sends brochures to top-notch high-school students with an interest in the humanities to encourage them to apply, says Debra Satz, the dean of Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. Prospective students can also take humanities classes at Stanford while still in high school.

What’s puzzling to the college officials I spoke to is that they say students’ interest in humanities majors remains high during the college-search process, according to what students indicate on their applications. Then something happens between when students apply and when they actually declare a major, usually in their sophomore year. Perhaps students’ intentions on their applications weren’t serious, but if they were, Satz says it’s critical that humanities courses in the freshman year capture their attention. At Stanford, she said introductory courses in the humanities are focused on “big ideas,” such as justice, ethics, and the environment, to appeal to students trying to choose their major.

“We have to make the offerings really good, really enriching,” Satz says. “Part of our challenge is when students see so many of their peers going into computer science.”

To help guide the course selection of incoming students, Grinnell sent a booklet to all freshmen this past summer that outlined the importance of a broad liberal-arts education. The college also added a session on the topic to orientation in advance of students meeting their academic advisers. Both initiatives, Kington said, were intended to encourage students to select courses across a range of academic disciplines, given that Grinnell lacks a traditional core curriculum with mandated requirements.

Macalester’s tactic has been to try to inject some humanities into STEM classes and some practical career training into the humanities. Last year, Rosenberg, the school’s president, brought the faculty together at a retreat to discuss the shifting balance of majors. One outcome was that faculty members were encouraged to pair together courses across academic disciplines so that, for example, a new class in social media might be a blend of computer science and philosophy. Professors in the humanities were also encouraged to give their students more career guidance than in the past, when many humanities students simply went to graduate school or law school after college.

“The typical English major is designed to get students to go to graduate school,” Rosenberg says. “We need to rethink the curriculum so that it’s more focused on what employers will immediately find attractive.”

Rosenberg was present when several presidents of elite colleges gathered last fall for a meeting in New York City. At our table during lunch, there was a debate about whether the changing distribution of majors was really a crisis. After all, at least at liberal-arts colleges, the humanities remain a central part of the curriculum, including for STEM majors. Indeed, Satz of Stanford says she’s less concerned about the 14 percent drop in humanities majors at the university over the past decade, and more focused on the 20 percent increase in enrollment in humanities courses.

“There’s only so much we can do to stem the tide in majors,” she says. “What I care about is that every student in engineering can think critically, can read carefully, and they can listen empathetically. That happens by taking courses in the humanities.”

Rosenberg, an English professor and Charles Dickens scholar by training, agrees. He says he doesn’t blame students for flocking to computer science and applied mathematics. Mathematical literacy and the ability to manipulate large data sets are becoming more critical in every job, including those the humanities traditionally trained, from journalists to sociologists. “We’re not giving students enough credit,” Rosenberg says. “They’re picking something that’s really interesting to them.”

Unless colleges in the United States want to follow the European model, where prospective students apply to specific degree programs instead of a given university, the choices of American students will likely always shift with the winds of employment. Some studies suggest that many of the tasks done by humans in STEM fields will be automated in the future; robots may well end up writing most programming and intelligent algorithms. So if elite colleges just wait long enough, perhaps the humanities will make a comeback as humans look for the kind of knowledge that helps them complement rather than compete with technology.

October, as it turns out, is not an optimal time to start sealing yourself into a tin can of humanity twice a day after years of riding the subway only occasionally.

I just got a new job at The Atlantic, and before that, I worked from home. Writing online doesn’t necessarily involve a lot of leaving the house, and most of the friends I see regularly live within walking distance of me, so for the past two years, I was, at most, a very occasional public-transit user. Because The Atlantic is an august establishment with an office and free snacks, starting this job meant I’d have to return to the subway-commute schedule that I abandoned in 2016.

Silently, I braced for the cold I feared that might bring, should my stay-at-home immune system not adjust quickly enough to its get-on-the-train future. And then, for a week, I took Amtraks and subways and shook hands with many incredibly kind strangers, all ready to welcome me into their professional lives.

Reader, I got a cold. And then I got this assignment.

[Read: Is gentrification the result of rich people’s quest for shorter commutes?]

The idea that public transportation will make you sick is an incredibly durable bit of pop-science wisdom, especially when you consider the relatively meager actual data on the topic, according to Stephen Morse, a professor of epidemiology at the Columbia University Medical Center. He says I was right that my newfound commute was a potential culprit, but not necessarily because of its newfoundness.

“I think it’s fair to say that in general, the flu and colds and other things are spread person to person,” Morse told me. “There’s no question that the more contact you have with people, the greater likelihood you are exposing yourself to infection. If you are a hermit and presumably have no contact with people, you are at very low risk.”

As with so many things in my past, leaving my house, in general, is probably where I went wrong. Before we get too finger-pointy at the subway, though, Morse cautions not to assume causation where mere correlation might be at hand. The main risk factor for contagion is proximity to other potentially sick people, no matter whether those people are on the train, in your office, or standing in line to get a lunchtime chopped salad just like you. So all those smiling faces, welcoming me to my new job with a firm handshake? One of them could have very easily been patient zero for my clogged sinuses, and how I got from my apartment to their cubicle or conference room wouldn’t have mattered at all. Cold and flu season is other people.

And in temperate regions like the northeastern United States, it really is a season—tropical and subtropical areas don’t experience the winter-specific cold and flu explosion that places with cold winter weather typically have, according to a 2016 study. So my big mistake might not have been getting on public transit or meeting my new coworkers, but instead, doing all that in the first chilly month of the year in New York. There have long been theories about why cold weather is a breeding ground for rhinovirus. It could be because you socialize more in close quarters when it’s cold out. A 2017 study from researchers at Yale University suggests the decreased temperature itself could be to blame. The study was conducted on mice, but it found that even a 7-degree dip in temperature was enough to suppress their natural immune response to infection.

[Read: Vaccine myth-busting can backfire]

If you’re feeling immunologically smug because you’ve been riding public transit to work every day for years and assume that’s built up your general resistance to illness, I hate to burst your bubble, but you have the same likelihood of coming down with the sniffles on any given day as anyone else who ventures along a similar path. People in this situation might be conflating their supposed resistance to the common cold with the hygiene hypothesis, according to Morse, which is the idea that allergic and autoimmune reactions are made worse when people are kept away from irritants, depriving their immune systems of the chance to build up a response. “The evidence on that is mixed,” Morse says. “And with colds and viruses, there are so many of them. If you ride the subway often, you’re likely to be exposed to more of them, and you may be getting colds more often.”

My two-year break from office work had not put me at an elevated risk for infection when I left the house—it had actually insulated me from a lot of small, daily potential exposures to illness. But now I have this job, which has been great so far, with the exception that getting to it requires me to star in my own low-budget remake of Contagion. Is there any way to fight back against the necessary health scourge of my own career, beyond becoming an independently wealthy and mysterious recluse? I spoke with Katherine Harmon, the senior director of category intelligence at the risk-management firm WorldAware, to see what she’d advise for both employers and employees looking to mitigate cold-weather risks. She told me to use hand sanitizer after I touch elevator buttons, and although I hadn’t ever really thought about how dirty those probably are, now I will think of nothing else for the rest of my life.

But according to Harmon, the biggest differences can be made by employers. “Making sure that people stay out an appropriate amount of time when they’re feeling ill is probably the single most important thing a company can do,” she says. And the best way to do that is for employers to let sick people take the time off they need and to let people work from home, in jobs where that’s feasible. (Lucky for me, I’m in one of those jobs.) “If somebody says they’re sick and they know they can work from home, there’s less of a risk of ‘presenteeism,’ which is when people who are sick come to work anyway because they’re obligated to be there,” says Harmon.

So if you want to stay healthy during cold and flu season and help others do the same, the answer is pretty simple: Stay home when you don’t feel well if at all possible, and bully (okay, “encourage”) your sniffly co-workers to do the same. You might not just be saving yourself, but also saving a woman on your train who doesn’t yet know the procedure to get permission to work from home at her new job.

Even Oscar Wilde, socialist and anarchist that he was, would likely bristle at the radical dysfunction of American politics today. Wilde famously preferred “everything in moderation, including moderation.” But 2018 may be the year that lawmakers and voters alike crystallize their preference for a slight spin on the playwright’s words: a Congress in which nothing is in moderation, except for moderation.

This shift has been some time coming. In the last midterm elections, in 2014, only about 4 percent of congressional candidates were ideologically moderate, according to data compiled by Danielle Thomsen, a political-science professor at UC Irvine, who categorized candidates by their campaign donors. The proportion of moderates on the campaign trail “has been steadily declining since the 1980s,” Thomsen told me. “It takes a lot of guts to run for Congress as a moderate in the current environment.”

This is not only because campaigns tend to favor personalities over policy goals and apocalyptic rhetoric over good-faith debate. It’s also because Congress itself disincentivizes reaching across the aisle. Work with a Democrat? Bid your perfect Heritage Action Scorecard farewell. Consider a GOP judicial nominee? Hope you weren’t too attached to that committee gavel.

It’s worth exploring, then, how moderate candidates today—however few they may be—manage to survive, and how they're pitching themselves in the final days of their midterm campaigns. The candidates and political strategists I've spoken with believe that constituencies that value compromise still exist, as well as voters who feel invested in issues rather than parties. Candidates have tailored their campaigns accordingly, focusing on local issues, largely uncontroversial national topics such as infrastructure, and as little talk of Donald Trump as possible. Call it the moderate playbook, whose fate in November could signal a new hope for bipartisanship—or affirm its extinction.

Harley Rouda is betting on that playbook to unseat a 28-year House incumbent. In Orange County, California, Rouda is challenging Dana Rohrabacher, the Kremlin-friendly Republican who’s been steadfast in his support for President Trump.

A liberal fantasy, Rouda is not. He’s a 56-year-old real-estate executive who donated to John Kasich’s presidential campaign and would rather not indulge in talk of impeachment.

He didn’t register as a Democrat until after the 2016 election; he’d been an Independent since 1997 and was a Republican before that.

He’s not the ideal conservative, either; he supports Medicare for all and free college tuition. But he’s still trying to attract conservatives to his campaign, which touts endorsements from local longtime Republicans. In one ad, a man wearing a palm-tree-emblazoned shirt lauds Rouda as “someone who can play to the middle, and bring us together.” It’s not unusual to see Republicans for Harley signs across Newport Beach and Balboa Island.

Rouda often refers to himself as “pro-business” and “pro-economy,” which have long been handy catchall descriptors for anything from regulatory relief to tax reform. It’s a smart move, one Democratic strategist told me, especially in Orange County, where pricey real estate and yacht-club-goers abound. “I have candidates create a list of what makes them different from a national Democrat,” said the strategist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of current involvement in midterm campaigns. “Often it’s that they served in the military or they run a business. That’s where a moderate campaign starts.”

Differentiating oneself from the national party is especially crucial in 2018, the source said, when candidates such as the self-described democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez dominate media coverage of the left. “The key is to be able to tell voters what you’re not,” the strategist said. “If you can’t find the few specific things to separate yourself, you’re starting from a real deficit.”

So voters won’t see a candidate like Rouda, for example, hypothesizing about Russian collusion or debating the merits of House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. Instead, he’ll lament that two years into Trump’s presidency, no infrastructure package has reached the floor. “We’ve had Infrastructure Week every week for 50 weeks,” Rouda told me in a recent phone interview. In his view, this is an example of how “continued partisan bickering and extremism” can prevent even an issue with “great bipartisan support” from moving forward.

When we talked, Rouda was careful to tie his discussion of any issue back to his district. This seems like a small point, but as campaigns continue to drift away from the Tip O’Neill–favored dictum that all politics is local, it may be crucial for Rouda as a moderate. When the candidate talked about health care, he talked about how his opponent had voted multiple times to eliminate coverage for preexisting conditions, which he said affected 300,000 people under the age of 65 in his district. When he talked about the environment, he talked about the need to contain the jet noise and pollution from John Wayne Airport, in Santa Ana.

The challenges on the campaign trail are steep for House and Senate hopefuls alike. The race for Senator Bob Corker’s seat in Tennessee lays this bare. Like Rouda, Democrat Phil Bredesen is adhering to the moderate playbook in the hopes of besting an ardently pro-Trump Republican. Bredesen, a popular former governor of the state, is challenging Representative Marsha Blackburn. John Tanner, a former Tennessee congressman who founded the Blue Dog Coalition—a group of the House’s most conservative Democrats—told me that Bredesen is the Platonic ideal of a moderate: “financially responsible and socially tolerant.” Blackburn, for her part, blends her views entirely with Trump’s. When the president held a rally for her in Nashville earlier this year, she focused her entire speech on supporting his agenda.

Tanner, who retired from Congress in 2010, said the race’s close polling gives him hope that voters do want a return to the middle. “But oftentimes they aren’t presented with that model,” he said.

Bredesen may be the only candidate, Democrat or Republican, whose press office has flooded my inbox with statements about the ballooning federal deficit, offering a plan (in all caps) to balance the budget within six years. Federal borrowing was once conservatives’ cause célèbre. But by the time Republicans shuttled through a massive tax-cut package late last year, even amid projections of a huge spike in the deficit, the issue seemed to have lost its appeal. Nevertheless, as with infrastructure, it remains a topic unlikely to draw partisan ire one way or the other—making it a valuable talking point for a candidate like Bredesen.

These issues are what candidates like Bredesen talk about instead of talking about Trump. Bredesen has largely avoided national media—he declined to be interviewed for this story—and thus the news of the day. One notable exception was Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination: Bredesen ultimately sided with his party’s lone yea, fellow moderate Joe Manchin, who’s facing a tough reelection in West Virginia. "If the FBI report had something in it which was much more strongly corroborative of [Christine Blasey Ford’s accusation of sexual assault], I think that would be a different issue," Bredesen told local media. "But it didn't, and of course I didn't get a chance to see what was in it."

Voters are more likely to hear Bredesen urgently discussing Asian carp. The fish has invaded much of West Tennessee, starving out native species, and this has hit the state’s commercial-fishing industry hard. This summer, Bredesen announced his agenda to curb the population. His campaign, according to a spokeswoman, has sold “hundreds” of hats that say Cut the carp.

Much like noise pollution from John Wayne Airport, Asian carp hardly matches the current tabloidlike nature of national politics. But as Tanner put it, “That’s a proper role for a legislator, in a campaign. You’re not running against Trump; you’re running for the Senate.”

A handful of incumbents in both chambers and parties have also pitched themselves as moderates in the 2018 midterm cycle. Democratic Senators Heidi Heitkamp, Joe Donnelly, and Manchin come to mind, as well as Republican Representatives Brian Fitzpatrick, Will Hurd, and Dave Joyce. But Rouda and Bredesen are not moderate incumbents desperately trying to stay afloat; they’re first-time candidates for Congress. Both men decided that even in this hyper-partisan moment, the moderate playbook was worth the gamble.

Yet Rouda and Bredesen are something like unicorns in the 2018 cycle. There are so few other moderate first-time candidates out there, underscoring just how hard it is to persuade a middle-of-the-road-minded person to run for elected office.

“It’s just gotten so contentious,” former Illinois Republican Representative Bob Dold, a moderate who lost his seat in 2016, told me. “You’re getting millions of dollars being spent against you on negative ads, and most of them aren’t even true. A lot of people will just say, ‘No, thank you,’ to that.”

The Democratic strategist Peter Cari told me that both parties are struggling to convince would-be moderate candidates of a viable path to victory. “When the right thinks anyone who votes for compromise is a sellout, and Democrats think the same thing, it makes it tough to want to run,” he said. “Everyone’s scared to death, and with reason.”

The arc of the moderate campaign is long and bends toward failure. Almost everyone I interviewed for this article said that gerrymandering was the chief culprit. Every 10 years, after the federal census, both parties exploit the ability to redraw districts and virtually guarantee their side’s dominance for the decade to come. It’s the reason, for example, a Republican stronghold like Maryland’s Sixth District was able to turn bright blue in 2011 with a few clicks of a computer mouse.

The result, as Dold explained to me, is a system in which “the primary is the election.” When a party reigns in a district without question, the real contest takes place during the primary. Democrats will try to outrun one another from the ideological left; Republicans attempt to pitch themselves as the field’s most conservative choice. Candidates in both parties often end up pandering to their base’s most extreme impulses, knowing that they won’t need to temper their message in the general election.

“I don’t think people realize or fully understand the corrosive effect that 50 years of gerrymandering has had on the system,” John Tanner said. “Gerrymandering has driven people who hold elected office into the red or blue world, where their only political jeopardy is in the primary. Not only is there no incentive to work across party lines; there’s actually a disincentive.”

Tanner is among the few lawmakers who have actively worked to regulate gerrymandering. “I had a bill each of my last four terms to change it,” he said. “But I couldn’t.” Meaningful change is unlikely anytime soon. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court declined to decide on the Maryland gerrymander’s constitutionality, sending the case back to a lower court on procedural grounds.

“This is the miserable system we’re stuck in,” Tanner concluded.

Duking it out in a primary, enduring waves of attack ads—that’s just getting to Congress. The challenges of the campaign trail are trivial compared with what moderates like Rouda and Bredesen would likely face in Washington itself.

Two of the most notable pieces of legislation in the past eight years—the Affordable Care Act and tax reform—passed the Senate without a single yea from the minority party. Kavanaugh’s confirmation process was a partisan bloodbath.

And ideological divisions within parties have become almost as fraught as cross-party relationships. A standoff between the House’s Republican leadership and the conservative Freedom Caucus is the rule, not the exception, for any legislative battle―preventing, for example, any progress on immigration reform. And as I reported last month, a group of House Democrats began pushing a measure that would make it more difficult for Nancy Pelosi to become speaker if her party takes the House—only to withdraw their petition when, at a caucus meeting a few days later, Pelosi herself showed up to address it.

Current lawmakers I spoke with expressed frustration with the gridlock. It’s an easy thing to pay lip service to. But representatives such as Tom Reed, a moderate New York Republican who watched as colleague after colleague announced his or her retirement this year—and who considered jumping ship himself—said they’re taking steps to ensure that the 116th Congress is different from past sessions.

Reed is the co-chair of the Problem Solvers Caucus, a group of centrist members that aims to achieve bipartisan consensus on major policies. Reed and his fellow co-chair, Democratic Representative Josh Gottheimer of New Jersey, formalized the 48-member coalition last year. The lawmakers are required to vote together on any bill that 75 percent of the caucus supports. Reed told me that when the group was developed informally in 2010, it had nearly 100 members. When he and Gottheimer introduced the consensus rule in 2017, the roster shrank by half.

Ahead of the midterm elections, 19 of the members have pledged not to vote for any speaker candidate who does not support a series of rules changes, such as forcing committees to send bills with more than 290 co-sponsors to the floor and making it easier for members to offer amendments to bills.

The proposed reforms are designed to shift power from the House majority leadership to more of the conference—and foster comity and cooperation in the process. “Unless leadership gives me the thumbs-up, I’m not allowed to get a bill to the floor. I’m not allowed to fail,” Reed said. “That frustration is shared widely.”

The Freedom Caucus blanched at a similar set of proposed changes in 2015, when Paul Ryan was up for the speaker post. Yet Reed said that he’s already succeeded in getting potential speaker candidates, including the ultraconservative Majority Whip Steve Scalise, to promise to support his group’s reforms this year. It’s a sign, perhaps, that the moderate caucus’s power could be growing. “I don’t want to be a bomb-thrower,” Reed told me. “I just want to be a member.”

The Senate is unlikely to consider similar changes—a smaller body means that legislators wield more power individually, and aren’t as hamstrung procedurally by leadership or a particular caucus. Yet whether senators are willing to break ranks is another question entirely; as Kavanaugh’s confirmation battle demonstrated, tribal fervor courses through the upper chamber as much as in the lower one.

Ultimately, November will be a test of whether moderate candidates still have a place in the American political system. If they do, this election will also test whether those candidates can stick to their centrist ideals. Will they strive to be a member, as Reed put it, or fall prey to the short-term promises of the bomb-throwers among them? The startling number of moderates who have chosen to retire in the past two years suggests that sticking to those ideals is too hard a task today. “The tragedy is that people who are being elected as slaves to one party or the other are just not able to govern,” Tanner said. “They can either resist or shove their agenda down someone else’s throat.”

Still, Bob Dold is optimistic that moderate lawmakers can be effective in Congress. “When I ran, we focused on accomplishments, working together, and being one of the most independent, bipartisan members of Congress,” he said. He told me that he was optimistic, too, that voters would ultimately reward such efforts at the ballot box.

He then paused for a few beats, realizing that losing his reelection in 2016 reflected just the opposite.

“I guess you can look at all that and say, ‘Yeah, but where did that land you?’”

Butch Otter, the outgoing Republican governor of Idaho, didn’t attract nearly as much attention for his big announcement on Tuesday as President Donald Trump did when he pledged to issue an executive order ending birthright citizenship.

But Otter’s endorsement of a ballot initiative to expand Medicaid in one of the nation’s most conservative states explains as much about the GOP’s situation in the 2018 midterm election as Trump’s legally implausible gambit; in fact, Otter’s move helps explain Trump’s.

In the final days of the midterm campaign, Trump and other Republicans are focusing their closing arguments on cultural confrontations, from immigration to the bitter confirmation fight over Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh. Otter’s announcement illuminates one key reason the party is placing so many chips on culture: GOP candidates appear to have lost faith that they can win the argument with voters over the key policies in their economic agenda, especially the longtime effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act and the huge tax cut Trump signed late last year.

[Read: The GOP is suddenly playing defense on health care ]

“They are ending up on the culture war because we have blunted them on taxes and they can’t talk about health care,” Democratic pollster Ben Tulchin said. “So they are left with one card to play.”

Republican candidates are still claiming credit for the buoyant economy, and some polls show them holding a substantial advantage over Democrats regarding which party can best promote prosperity. But the specific Republican policy initiatives that most directly affect voters’ economic circumstances haven’t proven nearly as popular.

While Republicans first expected the tax cut to anchor their midterm campaign, the public reaction to it has soured over the election year. An early October CNBC survey found that while 54 percent of Americans believe that the law provided “a lot of” benefits to large corporations, and 52 percent think that it similarly benefited the wealthy, the share who believe that it helped other groups is much smaller: 15 percent saw such gains for small business, 11 percent for average taxpayers, and a measly 8 percent for themselves personally. In campaigns across the country, Democrats have directly attacked the tax cut as a giveaway to the wealthy that will eventually compel Republicans to cut Social Security and Medicare.

The GOP’s relationship with the ACA is even more tenuous. For four consecutive elections, from 2010 through 2016, the vast majority of Republican candidates at every level ran on promises to repeal the ACA. But after Republicans gained unified control of Congress and the White House in 2016 and sought to repeal the law, they faced unexpected institutional and public resistance. Almost every major medical organization opposed repeal. And after years that saw more Americans opposing than backing the law, public opinion during the repeal fight tilted toward support, where it has remained ever since. In polling by the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation, individual elements of the law have proven even more popular.

Kaiser’s polling has found that nearly three-fifths of adults living in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA support doing so. Even more emphatically, about three-fourths of all Americans back the law’s requirement that insurers cover patients with preexisting conditions at no surcharge.

[Adam Serwer: Trumpism is ‘identity politics’ for white people]

Eliminating those protections was not an ancillary part of the GOP’s repeal legislation. It was an expression of the bill’s core philosophical argument: that the ACA compelled younger, healthy people to buy more insurance than they needed to subsidize consumers who were older or had greater health needs. Undoing that subsidy—or, more technically, disaggregating the risk pool—was the GOP plan’s central mechanism for lowering insurance premiums for the young and healthy. But the price of that was always reducing the affordability and availability of coverage for those who are old and sick.

One unequivocal message of the 2018 campaign is that the public rejects this trade. That clear consensus has compelled backflips from Republicans. Perhaps no one has become more contorted than Representative Martha McSally, now the GOP’s Senate candidate in Arizona. According to multiple sources, McSally, a former Air Force fighter pilot, rallied her colleagues with Top Gun swagger just before the repeal vote: “Let’s get this f-ing thing done,” she declared as legislators moved toward the floor. Now, in her television advertising, she insists that she’s “leading the fight” to “force insurance companies to cover preexisting conditions.” To borrow from her military career, that would define “leading the fight” as flying in precisely the opposite direction from the target.

McSally has plenty of company in shifting course. Trump, despite all evidence to the contrary, regularly insists that Republicans are more committed than Democrats to protecting consumers with preexisting conditions, even as his administration has joined a lawsuit to invalidate the ACA’s provisions doing exactly that. And while some Republican gubernatorial nominees continue to oppose Medicaid expansion (most prominently, Ron DeSantis in Florida and Brian Kemp in Georgia), others are hedging against Democratic opponents or wholeheartedly embracing it. In Ohio, GOP nominee Mike DeWine, after questioning the state’s Medicaid expansion during a Republican primary, endorsed it once he reached the general election. In Idaho, Lieutenant Governor Brad Little, who’s running to succeed Otter, has dodged a position on the ballot initiative but has promised to respect the will of the voters.

The fizzling of the tax bill and the backlash on health care help explain the GOP’s turn toward cultural confrontation in the campaign’s final turn. An even larger factor may be Trump’s apparent belief that he forges his strongest connection to the party’s preponderantly white base when he speaks to its anxieties about cultural and demographic change.

[Jay Caruso: I’m not leaving the Republican party]

That instinct has manifested in a glut of polarizing cultural signals from Trump over the past few days. These include sending the military to the Southwest border to resist what he calls “an invasion” of a convoy of Central American migrants; the hastily floated pledge to end birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants; and eliminating the transgender legal category under Title IX, which bars gender discrimination in education. Running like a backbeat through this policy flurry has been Trump’s stout defense of Kavanaugh, who faced multiple allegations of sexual assault, and the president’s warnings that men have been unfairly targeted by the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment.

Individual Republicans have dissented from some elements of Trump’s cultural offensive. (Most notably, House Speaker Paul Ryan dismissed Trump’s claim that he could end birthright citizenship through executive order.) But few Republicans are stepping off the train as Trump lurches even further to the right on immigration and other social issues. Even Ryan, while rejecting Trump’s means, didn’t express an opinion on his ends of terminating birthright citizenship. (That didn’t stop Trump from attacking him in a tweet on Wednesday.) Others, like South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, loudly echoed Trump’s call. By contrast, when the GOP platform in 1996 endorsed ending birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants, Bob Dole, as the party’s presidential nominee, publicly repudiated it.

All this follows the collapse of Republican skepticism on Trump’s border wall and the party’s turn toward opposing both illegal and legal immigration. Although proposed cuts in legal immigration didn’t pass Congress this year, about twice as many Senate Republicans supported it as they did in 1996, the last time Congress seriously debated the issue. Throughout the primary season, more mainstream Republican candidates fought off challenges from the Trump-inspired right by moving toward his racially infused nationalism, particularly through opposition to immigration.

Trump’s immigration-centered closing arguments show how thoroughly he believes that the GOP base is motivated not by rolling back government (through tax cuts or repealing the ACA) but by resisting cultural and demographic change. New national polling this week from the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute supports his instinct. That survey asked Americans whether they believed it was mostly positive or negative for the nation that minority groups will reach a majority of the U.S. population by 2045. While nearly two-thirds of all Americans and four-fifths of Democrats said that the change was mostly positive, slightly more than three-fifths of Republicans described it as mostly negative.

One of Trump’s most profound effects on American politics has been widening existing divides and accelerating ongoing trends. Long before he arrived, the parties were undergoing an overlapping demographic and geographic realignment, with Democrats mobilizing a “coalition of transformation” centered on the voters and regions most comfortable with racial, cultural, and even economic change, and Republicans countering with a “coalition of restoration” centered on the groups and places most resistant to it.

[Read: How the Democrats lost their way on immigration]

As Trump more overtly identifies the GOP with racial resentments and anxieties, this election seems destined to harden the lines and widen the trench between those inimical coalitions. The GOP’s final message in 2018 shows that it is relying more than ever on the cultural grievances of blue-collar white America in order to amass the political power to pass an economic agenda aimed primarily at those in the upper income brackets.

And yet the GOP appears at far greater risk next week of losing upper-middle-class voters on cultural grounds than it does of losing working-class voters for economic reasons. The major exception is a few midwestern industrial states, such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ohio, where Democrats appear to be clawing back into contention among working-class whites.

Trump’s closing emphasis on culture may, in fact, represent a kind of triage for the GOP that effectively concedes large suburban losses in the House, but tries to protect more rural and blue-collar districts, as well as GOP Senate candidates in states fitting the latter description. “That’s not an unreasonable interpretation of it,” Republican pollster Whit Ayres said. Trump’s cultural messaging, he added, “may help in some rural blue-collar districts, but it sure doesn’t help in the suburban districts that are so important to help keep the House.”

This re-sorting will push the GOP even further toward Trump’s politics of racial and social backlash, because in next week’s election it may doom many of the moderate suburban House members who most resist his direction. After November, the GOP caucus in both congressional chambers will almost certainly tilt even further toward predominantly white, heavily blue-collar, and religiously traditional places where Trump’s insular messaging resonates. The paradox that the final stage of the 2018 election reveals is this: As more upscale voters who benefit from the GOP’s economic agenda flee Trump’s racially infused definition of the party, Republicans will become even more dependent on stoking the cultural grievances of their working-class base.

In Thailand, a small group of Hmong women lived in a rural village, far from the nearest town. They grew everything they ate, mostly rice and vegetables. They boiled most of their food, and they rarely consumed meat.

But then something happened to these Hmong women that shocked their systems, permanently altering, in just a short time, the course of their health—as well as the very germs that dwelled inside of them. They immigrated to the United States.

In their new homeland—Minneapolis—they began to eat more protein, sugar, and fat. They indulged, like most Americans do, in processed food. Within a generation, the Hmong women went from having an obesity rate of 5 percent to one of more than 30 percent.

That statistic reflects one of the most vexing things about the well-being of immigrants in the U.S.: Many people who come to the U.S. for a better life end up with worse health. Many different studies have now shown that the longer certain groups live in the U.S., the worse some of their health outcomes get, especially when it comes to obesity. One study found that after one year in America, just 8 percent of immigrants are obese, but among those who have lived in the U.S. for 15 years, the obesity rate is 19 percent.

Using stool samples and dietary surveys from Hmong women living in Minneapolis, researchers from the University of Minnesota decided to see if the gut microbiome—the colony of bacteria that dwells in our intestinal tract—might play a role in immigrants’ obesity rates. In addition to Hmong immigrants, they recruited a group of Karen women who had previously lived in a refugee camp in Thailand. There, they had foraged in a nearby forest for food and had also eaten primarily rice and vegetables.

[Read: Vegan YouTube stars are held to impossible standards.]

The researchers compared the gut microbiota of Hmong and Karen women still living in Thailand with the gut microbiota of three groups: Hmong and Karen women who had immigrated to the U.S., these immigrants’ American-born children, and white American controls. The researchers also followed one group of 19 Karen refugees from their time in Thailand through their move to the U.S., tracking the components of their microbiota during their first year in America. (They limited the study to women because substantially more Hmong women than men were immigrating to the U.S.)

After about nine months in the U.S., the researchers found, the immigrants’ gut microbiomes had began to “westernize.” The microbiomes became less diverse—teeming with fewer types of bacteria—which is often associated with obesity. “Having low diversity in your microbiome is almost universally a sign of bad health, across almost every disease that has been studied,” says Dan Knights, a computational microbiologist at the University of Minnesota and a co-author of the study, which was published Thursday in the journal Cell.

The immigrants’ microbes became less able to digest certain types of fiber, and they shifted from being dominated by a type of bacteria called Prevotella to one called Bacteroides. Their gut microbiota, in other words, came to resemble those of the white Americans who acted as the control. The microbiome changes were even more pronounced among obese participants and in second-generation immigrants who were born in the U.S.

Cell

CellWhile the fact that microbiomes change as people move into different types of societies was already known, “to watch it happen six to nine months after people moved is startling,” says Justin Sonnenburg, a Stanford microbiologist who was not involved with the study.

However, this paper only showed that there is a correlation between westernization of the microbiome and obesity, not that one causes the other. And that’s a key piece of the microbiome puzzle that scientists are still missing. We don’t know if eating a less-healthy diet makes you obese and changes your microbiome, or if it changes your microbiome so it makes you obese.

Kelly Swanson, a nutritionist at the University of Illinois, for one, says that while “the microbiota are important for health, I don’t blame the obesity on bacteria. There are other things driving the ship.”

There is some evidence that bacteria alone can spur weight gain. In 2013, when scientists took the gut bacteria from one fat human twin and one skinny twin and implanted them into mice, the mice that received the fat twin’s bacteria grew fat, while the skinny-twin mice stayed thin. What’s more, when the mice were housed together, they tended to eat one another’s poop. When that happened, the skinny-twin bacteria would invade and colonize the guts of the other mice, even though the other mice had already been given the fat-twin bacteria. Those invaded mice, in turn, would lose weight. This meant “lean” gut bacteria can sometimes invade and conquer “fat” bacteria, but not, in this case, the other way around.

Here’s the twist: In that experiment, it was Bacteroides, the same bacteria that ended up dominating the immigrants’ microbes, that did the colonizing and the tamping down of the “fat” bacteria. In other words, even though it’s been associated with various diseases, it looks like Bacteroides can, in some cases, be a good guy. “And that’s one of the million-dollar questions: Are these [microbiome] changes bad?” Sonnenburg says.

After all, it’s little surprise that our microbes might change with our diets. The Prevotella strains that were wiped out among the Hmong and Karen people were used for digesting foods like tamarind, palm, and coconut. “It makes sense that if people stopped eating those foods, the microbes that used to subsist on them would go away,” Knights says.