Still Gone: Saudi Arabia has acknowledged the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, though Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has insisted he was never involved, leaving an incomplete outline of horrific events. Amid the ongoing crisis, a delegation of American evangelical Christians, including some of President Donald Trump’s advisers, moved forward on a meeting with the crown prince. “Do you believe MbS when he says he didn’t authorize the murder?” Sigal Samuel asked one of the delegates. Read his response.

Mueller … : Special Counsel Robert Mueller is spoken of often but never speaks himself (zero public words since his appointment 18 months ago), as Washington awaits his final report. With an acting attorney general reportedly skeptical of the Russia investigation’s scope, Mueller and his team may still have recourse should the new attorney general take steps to gut their work. In any case, Benjamin Wittes argues, there are multiple reasons why the window of opportunity to fire Mueller has passed.

Kristallnacht: On the 80th anniversary of a night of pogroms against Jews throughout Germany and Austria, David Frum reflects on the potent lesson history has to offer. And in this short film, several Holocaust survivors recall their experiences in Weimar Germany and the early days of the Nazi regime.

Snapshot A wildfire whipped through Paradise in Northern California near Sacramento, burning down the city and displacing tens of thousands of people. Now wildfires are threatening other parts of the state. 13,000 residents of the beach city Malibu have been ordered to evacuate. What causes California’s wildfires, and how can they be stopped—or even just slowed? (Justin Sullivan / Getty)Evening Read

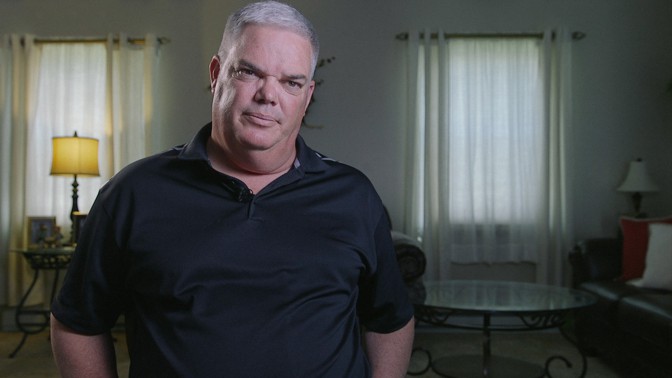

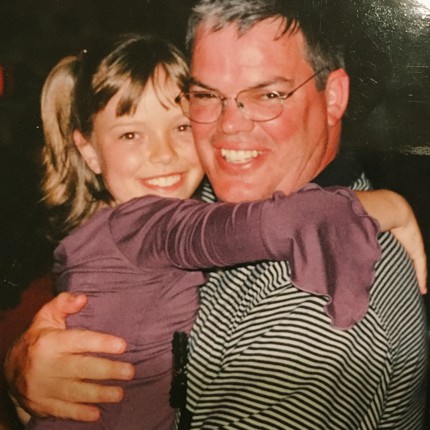

A wildfire whipped through Paradise in Northern California near Sacramento, burning down the city and displacing tens of thousands of people. Now wildfires are threatening other parts of the state. 13,000 residents of the beach city Malibu have been ordered to evacuate. What causes California’s wildfires, and how can they be stopped—or even just slowed? (Justin Sullivan / Getty)Evening ReadAs a narcotics officer, Kevin Simmers locked up hundreds of drug users—including his own daughter—as the opioid epidemic worsened:

Just nine days after [his daughter] Brooke’s release, Simmers awoke to tire tracks through the front yard—Brooke had apparently maneuvered around his car. Hours later, Dana Simmers received a call from Brooke’s friend Alison Shumaker, who told her she had spoken to Brooke in the predawn hours. Shumaker, who was trying to quit heroin herself, said that Brooke had relapsed and, full of self-loathing, had told her, “I’m a piece of shit.” In a recent interview, Shumaker recalled that Brooke feared her father’s response, and told Shumaker, “I can’t go home. He’s going to be so disappointed.” Eventually, the line went silent.

“She might have died talking on the phone with me,” Shumaker said. The possibility that faster action may have saved Brooke’s life haunts Shumaker, but her inaction is not unique. Research suggests that after decades of Simmers-style drug policing, the most important reason drug users don’t seek timely medical help is the fear of prosecution.

Simmers later changed his mind on the War on Drugs. Read on.

What Do You Know … About Culture?1. The final season of this Netflix drama, featuring a truncated season, ends “on the cynical cliché that every new master will be just like the old one,” writes our critic Spencer Kornhaber.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. “Sour Milk Sea” was one of the songs written for possible inclusion in this famous 1968 album, now reissued 50 years later to include the demos and sessions that ended up on the cutting-room floor.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. In The Front Runner, Hugh Jackman plays this American politician, whose promising 1988 presidential campaign came to a halt after allegations of an extramarital affair.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: house of cards / White Album / Gary Hart

Poem of the WeekSunday marks 100 years from the official end to the fighting in World War I. Here, a portion of “Red Seed” by Fannie Stearns Davis, published in our June 1919 issue, captures the uneasiness of the ensuing peace:

Now perhaps there is Peace.

But dare you say that you know it? …

The Wind caught a wild red seed,

And is wild to blow it

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Atlantic Daily, and we welcome your thoughts as we work to make a better newsletter for you.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Written by Madeleine Carlisle (@maddiecarlisle2), Olivia Paschal (@oliviacpaschal), and Elaine Godfrey (@elainejgodfrey)

Today in 5 LinesThe Wall Street Journal reported that President Donald Trump was involved in “nearly every step” of hush-money agreements with former adult-film star Stormy Daniels and ex-Playboy model Karen McDougal. Trump has repeatedly denied any involvement.

A wildfire in Northern California killed at least five people in the city of Paradise, authorities said. Several thousand people have been evacuated in Southern California due to a second wildfire near Los Angeles.

Democrat Kyrsten Sinema gained a small lead over Republican Martha McSally in the Arizona Senate race, which is still too close to call.

The Florida recount for the governor and Senate races is still underway, and embroiled in lawsuits and allegations of voter suppression and voter fraud.

Cesar Sayoc, the man who allegedly sent at least 16 pipe bombs by mail to some of the president’s most vocal critics, was indicted on 30 counts.

Today on The AtlanticThe Activist Dilemma: Leftist activists are driving the Democratic Party’s agenda, writes Peter Beinart in the December issue of The Atlantic. Could they go too far?

It’s Too Late: With Jeff Sessions gone, many are worried that Trump might act to rein in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation. Benjamin Wittes offers 10 reasons why that probably won’t happen.

An Unexpected Upset: Here’s how a 27-year-old graduate student with no government experience toppled a highly respected Republican moderate in Houston. (Andrew Kragie)

Spaced Out: Trump needs Congress if he wants to create a Space Force. But the Democratic House will probably ground the project, reports Marina Koren.

Snapshot A White House staff member, on the right, carries personal luggage and papers for President Donald Trump and first lady Melania Trump to Air Force One before Trump’s departure for Paris. A military aide follows with briefcases containing the military launch codes, known as the nuclear football. (Carlos Barria / Reuters)What We’re Reading

A White House staff member, on the right, carries personal luggage and papers for President Donald Trump and first lady Melania Trump to Air Force One before Trump’s departure for Paris. A military aide follows with briefcases containing the military launch codes, known as the nuclear football. (Carlos Barria / Reuters)What We’re ReadingWhy Are Democrats So Sad?: They wanted the midterm elections to be a total rebuke of Trump, writes Amy Walter. And that didn’t happen. (The Cook Political Report)

Still No Governor in Georgia: Less than two percent of votes separate Democrat Stacey Abrams from Republican Brian Kemp—and Abrams won’t concede until every vote is counted. (Amanda Arnold, New York)

Big Money, Big Wins: Affordable-housing activists across the country were hoping to pass progressive reform policies in Tuesday’s midterm elections. But after the real estate industry got involved, many of their initiatives lost. (Jimmy Tobias, The Nation)

Not an Excuse: After every mass shooting, the National Rifle Association and its allies argue that the problem is the mental health of the perpetrators, not the guns themselves. That’s wrong, argues Elizabeth Bruenig. (The Washington Post)

On the Other Hand: Gun-control advocates argue that reasonable gun laws would prevent mass shootings. But those laws didn’t prevent the most recent massacre in California. (Jacob Sullum, Reason)

VisualizedPeople Showed Up: Turnout in midterm elections is usually much lower in presidential ones. However, these 13 states actually increased turnout compared to 2016. (Dan Keating and Kate Rabinowitz, The Washington Post)

Six for Six: These six first-time candidates attempted to flip their congressional districts from red to blue this year. All six won. (Diane Tsai and Charlotte Alter, Time)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

A delegation of American evangelical Christians met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman last week in Riyadh. The group included some of President Trump’s top evangelical advisers, though they weren’t there in any official capacity. They’d come to talk about religious freedom with the young, self-styled reformer. But they found the trip overshadowed by the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

The kingdom has acknowledged responsibility for the murder. The crown prince, known as MbS, says he did not authorize it. While the delegation knew it would be controversial to visit him in the wake of the crisis, they decided to go ahead with the trip, which was planned before the Khashoggi affair came to light.

“I think it would have been immoral not to accept this invitation, because of the potential implications of it in the long-run,” Johnnie Moore, a delegate who serves on the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, told me. He’d come to advocate for the religious rights of the 1.4 million Christians who are estimated to live in Saudi Arabia, though reliable figures are difficult to find (legally, all citizens are required to be Muslim).

This wasn’t his first such trip: He and his fellow evangelical delegates had just visited the United Arab Emirates, and last year they traveled to Egypt to meet with President Abdel Fattah El Sisi. Moore told me they aim to build bridges between Islamic and Christian communities across the Middle East as a means of “making sure our community is thought of and represented.”

Yet one could see his group’s decision to sit down with MbS at such a precarious moment as legitimizing the kingdom’s human-rights violations. Moore and I discussed that risk, as well as his impressions of the crown prince, whom he described as philosophical and introspective. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Sigal Samuel: What was the goal of your trip?

Johnnie Moore: Evangelicals are now 60 million in the United States, and there are at least 600 million around the world. It’s one of the largest segments of the Christian Church. So for a group of evangelicals to be invited for a dialogue in what has long been considered one of the most restrictive countries in the world as it relates to religious freedom, that’s really important to us.

Religious freedom was the focus. We all had the opportunity to ask questions along the way, and my specific questions related to churches in Saudi Arabia. Of course, right now, there isn’t a single church building, there’s certainly not a synagogue, it’s a country full of countless thousands of mosques. … That’s not to say there isn’t worship of other kinds that takes place quietly, in people’s homes. … But when it comes to public worship it’s a different story.

Samuel: What did MbS say about the possibility of churches being built in the kingdom?

Moore: He said, “I’m not prepared to do that now. And the reason is because it’s the one thing that al-Qaeda and [the Islamic State] and the terrorists want. If I did it now, bombs would fall, and it would not be the right thing for the safety of our people.” … He made the point that it would embolden the terrorists and extremists, so you shouldn’t plan on it anytime in the future.

I found it to be a thoughtful, logical response even though it’s not the response I hoped for. ... It wasn’t this visceral anti-Christian sentiment.

On the contrary, he made it a point to mention the wonderful meetings he’d had with the Coptic pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury. … You can’t deny the significance of those actions. And I think they were not actions principally meant to send a message to the West. They were principally meant to send a message within his own country, that this is an appropriate and reasonable thing for Saudi leaders to do. And I believe that even more because it fits into the greater context of our discussion, which was about very strategic actions they’re taking to move the country in the direction of reform.

[Read Jeffrey Goldberg’s interview with Mohammed bin Salman]

Samuel: Did you ask MbS about the murder of Jamal Khashoggi?

Moore: It was the first question we asked. We knew we were going in this context … so we weren’t going to dodge it. We just asked it outright. He was totally consistent with what he’d said publicly before—he said this is a terrible and heinous act and they were going to find and prosecute everyone involved with it. He emphatically denied involvement.

But then he got sort of introspective and he said, “I may have caused some of our people to love our kingdom too much, and therefore to take their delegated authority and do something heinous that they absurdly thought would be pleasing.”

He was making sort of a philosophical observation—which he did quite a bit actually—he’s a really interesting figure.

Samuel: Do you believe MbS when he says he didn’t authorize the murder?

Moore: I’m choosing not to have an opinion on that, because I’m focused on other things. My focus is on the long game, on the long-term status of religious freedom in the region. It’s not that I’m not disgusted by the whole thing, but … my choice is to take at face value what the Saudis are saying, and focus on the area that I can actually have an impact on.

I’m very much a realist in this way: I’m a religious freedom advocate. That’s the only thing I am.

Samuel: It seems to me that there’s an unbundling of religious freedom from human rights. Religious freedom is one part of human rights. It seems that under the Trump administration especially, there’s been a lot of talk about religious freedom, almost in a one-to-one mapping with human rights—as if the two are coextensive. But can we justify fighting solely for religious freedom concerns and putting to the side human-rights concerns like the war in Yemen, like the imprisonment of women’s-rights activists?

[Read: Pence declares global religious freedom a “priority of the Trump administration”]

Moore: I think it’s a totally worthwhile criticism. I don’t disagree with you. I do think that in previous administrations the value of religious freedom has been many degrees below the value attributed to general human-rights advocacy. This administration has a perspective that it’s easier to move the overall human-rights agenda through the religious freedom channel.

Oftentimes, the human-rights questions, you can’t untangle the politics from it. With religious freedom, when I sit down—as a devout Christian with degrees in religion, as an ordained minister—across the table from an Islamic leader who’s devout and theologically trained, I have other things to talk about than politics. So tactically, there is a perspective that we can move the needle more easily in the area of religious freedom, and the concomitant effect will be making it easier to move the needle on other human-rights issues. It’s like, when the ocean rises all ships rise.

The Saudi crown prince meets with evangelicals in his palace (Reuters / Saudi Royal Court)

The Saudi crown prince meets with evangelicals in his palace (Reuters / Saudi Royal Court)Samuel: I think that’s a really interesting point. To me, the risk of that approach is that focusing on religious freedom and appearing willing to unbundle that from broader human-rights concerns—it risks giving the Saudis the impression that it’s okay. That here are these devout U.S. leaders who are close to the president and they’re unbothered enough by the human-rights concerns that they’re willing to sit down and talk about other things. Do you perceive that as a risk?

Moore: Well, first of all, if you’re concerned about risks, you’re going to get nothing done in the Middle East, at any time with anyone in any way. It’s just the most complicated region in the world. Risk is not something I pay very much attention to. …

I actually think the exact opposite happened. ... As religious leaders we had another connection point [with MbS]. We didn’t find him defensive at all. And we didn’t find him spinning. If he was spinning, he would have given us a different answer on the church question. It was two and a half hours of an open conversation, I think precisely because we are religious leaders.

Samuel: I think that what people have difficulty with in regards to MbS is that, even as he paints himself as a reformer he does things that seem to cut directly against that. So for example, he depicted himself as being very pro-women’s rights, lifted the ban on women driving, but also imprisoned some of the very women who campaigned for that right to drive. People have difficulty squaring the two MbS’s.

Moore: The phrase you just used is a key to the observation: “squaring the two.” That’s a very Greco-Roman, Western way of Americans trying to get their heads around this—not you, I know you’ve spent time in the region. One of my favorite phrases when it comes to the Middle East is, it’s all true. And you can choose to take the long view or the short view. I take the long view.

If you take the long view, you engage when these people are ready to engage. And you do it on their terms.

In a little-noticed hearing this week before the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, attorneys for Special Counsel Robert Mueller laid out how much authority the acting attorney general has over the Russia investigation, including the ability to reject a proposed subpoena and scuttle an indictment. Although on its face the hearing had little to do with Matthew Whitaker, the man President Donald Trump just appointed to the post, it raised fresh questions about how far Whitaker could hypothetically go in gutting the investigation—and how the special counsel could fight back.

On Thursday, a three-judge panel considered a legal challenge to Mueller’s authority brought by an assistant to Roger Stone, the longtime Trump confidant who is being investigated by Mueller for his ties to Russia and WikiLeaks. The aide, Andrew Miller, has been trying to fend off a grand-jury subpoena issued by Mueller earlier this year. Miller’s lawyers tried to argue that Mueller’s work isn’t lawful, saying that he’s effectively acting as a principal officer of the U.S. government without having gone through the proper Senate confirmation process that position requires. (“Principal officers” include Cabinet officials, among other posts.) But Michael Dreeben, Mueller’s lawyer, insisted that Mueller doesn’t qualify as a principal officer, because he “has a regular reporting obligation to the acting attorney general.”

Who Mueller reports to is of major consequence. Jeff Sessions, the former attorney general, had recused himself from oversight of the federal Russia investigation, so Mueller reported to his deputy, Rod Rosenstein. Now that Trump has fired Sessions, those oversight responsibilities fall to his replacement, Whitaker, who has previously expressed skepticism about the scope of Mueller’s probe.

And in that role, as Dreeben explained in court, Whitaker has significant power: While Mueller’s team is “independent on a day-to-day basis,” if the acting attorney general found anything to be “inappropriate” or “unwarranted,” he could intervene. Indeed, the special-counsel guidelines allow the acting attorney general to overrule any “investigative or procedural step” proposed by Mueller if the move is deemed “inappropriate or unwarranted under established department practices.”

It’s unknown whether Whitaker would shut down Mueller’s investigation if the president asked. But Dreeben’s explanation suggests that Whitaker need not fire Mueller in order to stymie his work. Whitaker wrote last year that the Mueller inquiry had “gone too far” and opined on CNN about the ability of a potential Sessions replacement to grind the investigation almost to a halt. He could opt for a death-by-a-thousand-cuts approach instead of risking the inevitable political blowback from firing Mueller directly. And he could try to hinder Mueller from revealing his findings without having to justify his decision to Congress until after the probe is over.

“According to the regulations, should the attorney general determine that an action is so inappropriate that it must not be pursued, he or she has to report that to Congress along with the justification,” several national-security–law experts wrote in Lawfare earlier this week. “Such a report, however, is not required until the ‘conclusion of the Special Counsel’s investigation,’ so this oversight protection is unlikely to be helpful in the short term.

“Put simply,” they continued, “if someone in Whitaker’s new role wants to create big problems for Mueller, he has ample tools to do so.”

The D.C. circuit court is now examining what influence, if any, Sessions’s ouster and Whitaker’s appointment could have on the Miller case. It is possible that the court will decide that Rosenstein, not Whitaker, is Mueller’s rightful boss, according to Neal Katyal, a former acting solicitor general under President Barack Obama.

Short of that conclusion, however, Mueller may have some recourse in the event that Whitaker maintains control over the investigation and attempts to either suppress it or shut it down. Several legal experts have argued that Trump’s appointment of Whitaker may have been unconstitutional. At issue is the same question of who qualifies as a principal officer. Because Whitaker reports directly to the president, he is a principal officer, these experts say, and would have required Senate confirmation.

“That has a very significant consequence today,” Katyal and the conservative lawyer George Conway wrote in The New York Times on Thursday, citing Justice Clarence Thomas’s opinion in National Labor Relations Board v. SW General, Inc. “It means that Mr. Trump’s installation of Matthew Whitaker ... is unconstitutional. It’s illegal. And it means that anything Mr. Whitaker does, or tries to do, in that position is invalid.”

Questions over Whitaker’s legitimacy could work to Mueller’s advantage, according to Jens David Ohlin, a professor at Cornell Law School who specializes in criminal law. Ohlin explained that Mueller could challenge Whitaker’s appointment in federal court on both statutory and constitutional grounds, the latter of which is “most likely to succeed.”

“In order to get either of these issues before a federal court, someone needs standing to bring the claim, which means they’ve been specifically harmed,” Ohlin told me. “If Mueller is fired, which is Whitaker’s ‘nuclear option,’ Mueller certainly has standing to object to Whitaker’s appointment.”

He added that Trump’s decision to appoint a “constitutional nobody” to head the Justice Department “is so far from mainstream practice” that a federal court would likely “scrutinize this carefully and would be skeptical that this is consistent with the [Constitution’s] Appointments Clause,” which outlines how appointments are to be made. Before he went to work at the Justice Department under Sessions, Whitaker served as the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Iowa from 2004 to 2009, then worked in private practice and appeared as a cable-news pundit throughout 2017.

Marty Lederman, who served as the deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel under Obama, is less sure, writing Thursday that the constitutionality of Whitaker’s appointment is “technically an open question.” But he tentatively assumed that “anyone who suffers an ‘injury in fact’ by virtue of something Whitaker does would have … standing to challenge his appointment in court.”

William Yeomans, a former deputy assistant attorney general who spent 26 years at the Justice Department, had similar reservations. “I think the constitutional argument is more complicated than many are suggesting and I am undecided,” he told me. Yeomans noted, however, that if Whitaker’s appointment was unlawful, Mueller “theoretically could refuse to carry out his instructions and could contest, for example, his firing.”

Whether Mueller would actually take such a dramatic step is another question. Paul Rosenzweig, a former senior counsel on the Whitewater investigation in the 1990s, doubted that Mueller would challenge Whitaker’s appointment, “both because it is no slam dunk legally and because he is bound” as a Justice Department employee by the opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel, which concluded in 2003 that “a Senate-confirmed position may be temporarily filled on an acting basis” by any “officer or employee” who “has served in the agency for at least 90 days in the preceding 365 days”—regardless of whether they are confirmed by the Senate. “It is also strategically incautious,” Rosenzweig said.

Still, if Mueller were to challenge Whitaker, one “solid way” to do it would be to defy him, Rosenzweig said, setting up a “live case” in which the court would have to address Whitaker’s legitimacy directly.

Mueller is not known for disobedience or public spectacles. In the 18 months since he was appointed, he has not said a single word about the Russia investigation, and his spokesman is best known for declining to comment in response to press inquiries. With his final report already in the works, however, and various elements of the investigation farmed out to prosecutors in New York and Washington, D.C., it is unlikely that Mueller’s findings—as they relate to a potential conspiracy between the Trump campaign and Russia—will never see the light of day.

If Whitaker were to refuse to release Mueller’s final report, for example, Mueller and the grand jury could make their evidence available to Congress through a report transmitted by the court, as the former Watergate prosecutors Richard Ben-Veniste and George Frampton recently noted. And “with the fox now guarding the henhouse,” they wrote, “there is sufficient precedent” for them to do so.

A visit to the Swiss Museum of Transport, NATO soldiers on patrol in Afghanistan, a giant’s house in Russia, new advances in powered exoskeleton technology, Californians mourn the victims of a mass shooting as they brace for destructive wildfires, autumn colors pass their peak in the North, Victoria’s Secret holds a fashion show in New York City, Bonfire Night across England, observing the centenary of the end of World War I, and much more

“Women’s anger is not taken seriously as politically consequential and valid, in part because women are sucked back into a maternal or wifely aesthetic framework,” Rebecca Traister said in a recent interview with The Masthead, The Atlantic’s membership program. “We need to understand their fury as politically and socially catalytic.”

In November, as part of The Masthead Book Club, members read Traister’s Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger. Members discussed the book on The Masthead forums with Atlantic staff, and submitted questions for Traister via video. Watch the conversation, and read on for an excerpt:

Is female anger really always taken less seriously? While reading the book, a a member reminded me of the phrase, “When mama’s unhappy, everyone’s unhappy.” It seemed to her that, especially when women invoke their roles as wives and mothers when angry, their anger is extremely effective. — Caroline Kitchener

Rebecca Traister: That is historically the context in which women have been offered what power is on the table. Their power is within a domestic sphere, within familial relationships. But if the only way we can invoke our authority is by making a comparison to a domestic and maternal sphere, that’s a very limited scope. Part of what this book is about is the fact that women’s anger is not taken seriously as politically consequential and valid, in part because women are sucked back into a maternal or wifely aesthetic framework. And we need to understand their fury as politically and socially catalytic.

Are movements like #MeToo and #TimesUp making a difference? — Barbara Didrichsen, Masthead member

Traister: Sure, they are making a difference insofar as there’s actually a difference in how consequences are being meted out. For years, even for very specific men about whom allegations have been made, those allegations were out in public for years and years and years. Nobody did anything about it.

I reported on sexual-harassment allegations against Bill O’Reilly when I was a young reporter in 2004. He remained the top anchor of Fox News, a network that was so powerful, it propelled presidents into office. So am I shocked by what has happened in the past year, that some of those very specific men lost their perches? Yes. But we should also remember that they didn’t lose their power.

It’s important to note that the No. 1 book on the best-seller list is written by Bill O’Reilly. He may have lost his perch at Fox, and that’s important, but he has not lost his voice, or his ability to make millions of dollars.

Do you think that the Ford-Kavanaugh hearings, and Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, might allow women to hear each other in new ways, and make greater strides against institutional oppressions? — Barbara Kellam-Scott, Masthead member

Traister: What happened with Brett Kavanaugh long-term is going to be formative—ultimately, probably, catalytic—in a way that’s hard to recognize right now. What was made visible to so many Americans in those weeks of September and early October is going to have a galvanizing effect on young people.

I do some of the work I do today because I sat and watched Anita Hill 27 years ago in high school. There are young and old people whose lives and views of how power works in this country and is abused has been shaped by what has just happened. I believe that 30 years from now, there’s going to be a journalist telling us about how Ana Archila and Maria Gallagher demanding Jeff Flake look at them in the eyes in the elevator was a catalytic, communicative movement, a way of channeling the fury of so many millions of women who are isolated in their homes, who couldn’t be in that elevator and couldn’t be at that protest, but felt their fury communicated. We’re going to say that was a moment of political import, in ways that we can’t predict now.

The Masthead Book Club chooses a new title each month—previous selections include Educated by Tara Westover, Political Tribes by Amy Chua, and The Road to Unfreedom by Timothy Snyder. This month we’re reading The Library Book by Susan Orlean. To learn more about the Book Club and The Masthead, visit www.theatlantic.com/join.

The killing of 12 people Wednesday night in Thousand Oaks, California, represents the second mass attack against gatherings of country-music fans in a little more than a year. Unthinkably, among the patrons of the “College Country Night” at the Borderline Bar and Grill were people who survived the massacre at Las Vegas’s Route 91 Harvest Festival in October 2017.

Gun violence is a hazard of American life whether in city streets or synagogues, but the targeting of country fans involves its own sort of politics. Mass shootings regularly result in calls for gun control, which in turn prompt a response from gun-rights advocates—many of whom listen to and make country music. Taste of Country’s “10 Best Gun Songs” list had plenty of material to work with. The NRA has a branch devoted specifically to strengthening the bonds between the lobbying group and Nashville.

It is that bond that Rosanne Cash spotlighted with a widely discussed New York Times column published after the Las Vegas massacre, headlined, “Country Musicians, Stand Up to the N.R.A.” “Not everyone will like you for taking a stand,” she wrote to her peers as she urged them to support gun control. “Let it roll off your back. Some people may burn your records or ask for refunds for tickets to your concerts. Whatever. Find the strength of moral conviction, even if it comes with a price tag, which it will.”

The year since hasn’t quite seen a revolution in country’s politics on firearms. Many mainstream artists have stayed vague on the issue, though there have been statements on behalf of gun control from Faith Hill, Tim McGraw, Maren Morris, and Jason Aldean, who was performing onstage when the shooting began in Vegas.

Cash is still speaking out. The day after the Thousand Oaks shooting, she tweeted: “12 killed, including the ‘good guy with a gun,’ plus survivors of Las Vegas shooting. We can’t go on like this. I don’t want to hear about thoughts and prayers. I want #GunControlNow.” She followed up with a specific call for a ban on high-capacity magazines.

I spoke with her that same day. This conversation has been edited.

Spencer Kornhaber: I wanted to get a perspective on Thousand Oaks from someone who’s a figurehead in country music and has been vocal about guns.

Rosanne Cash: We should clear up the fact that I’m not a figurehead in country music. In some ways, I’m persona non grata in country music. The Americana community has embraced me; I love country music and used to be part of the mainstream, but not anymore. So I can’t pretend to speak for country artists or that community.

I wish there were more people outspoken about this issue in country music. They all seem afraid to do it because of the blowback, and some of them have sponsorship relationships with the NRA, which is deeply troubling because somehow people have conflated country music, patriotism, and guns. Those threads have to be pulled apart.

Shootings like Las Vegas happen in the equivalent of a musician’s office. That’s where we work. So for people to say, “Shut up and sing; you don’t have a right to talk about this”: Well, it affects us. This Thousand Oaks shooting happened just 15 miles from where I grew up in Ventura, California. To read that some of the survivors also survived Las Vegas, it’s incomprehensible—the trauma these people have endured.

Kornhaber: How do you respond to those who say that guns are part of country music’s identity?

Cash: Look, I don’t vilify all gun owners. I don’t think a responsible citizen shouldn’t have their own handgun or shooting rifle. Most of the men in my family hunt. I don’t have any problem with that. But to be able to have a personal arsenal of military-style weapons is wrong. No civilized society should allow that.

I served for 10 years on the board of this organization [PAX, later renamed and merged with the Brady Campaign] that was devoted to protecting children from gun violence. And I met grieving parent after grieving parent until it was crushing me. These secret pockets of the deepest suffering imaginable are scattered throughout the country, and you can go your whole life without knowing they exist. When a child is killed by random gun violence, it shatters so many lives, from the parent to the family to the extended family to the school to the city. The suffering is multigenerational.

Kornhaber: You tweeted about gun control, and some of the replies pointed out that California already has strong firearm regulations and in fact recently passed some more.

Cash: It’s as if they think California is an island. Chicago has some of the strictest gun laws. People go across the border to Indiana to buy the guns. This should be a federal law.

Kornhaber: The attacker in Thousand Oaks was using a handgun that is legal in California, but also an extended magazine, which may have been banned there.

Cash: Yeah, I don’t know how he got it. Step back and take the wide view and see that we have a systemic problem in this country. These were college kids, right? We use young people as collateral damage for the Second Amendment, and it’s wrong.

Kornhaber: Have country artists taken up your call in the last year to speak out against the NRA?

Cash: No. There’s a lot of fear. Particularly from younger artists who know the blowback they’ll get. Look at the blowback Taylor Swift got for just telling people to vote. I’ve gotten threats for speaking out. Like I said in the op-ed, people wanted to kill us because we spoke out against gun violence. There’s a level of insanity that’s taken root.

I heard from some musicians, privately, after Las Vegas and the op-ed, [who] said, “Thank you; my mind has been changed by this.” But very few came out publicly.

Kornhaber: How have you tackled this issue as an artist?

Cash: There’s a song, on my new record, that I did with Kris Kristofferson and Elvis Costello called “8 Gods of Harlem.” I’d recently read about a kid being killed in Harlem by gun violence, and we played it out like a theater piece: I wrote the mother’s, Kris wrote the father’s, Elvis wrote the brother’s point of view. I think it’s a powerful song. I mean, I don’t know if it’s going to change anybody’s mind—people are entrenched. But you have to say what’s in your heart, don’t you?

Kornhaber: You also sang on Mark Erelli’s recent song about gun violence, “By Degrees.”

Cash: That’s a heartbreaking song. It was subtle and so sharp at the same time. Like, you can learn to live with the worst imaginable possible thing when it’s happening incrementally. You don’t notice until there’s carnage all around you and the fabric of your country is torn apart.

Kornhaber: Your New York Times column mentioned that gun-rights proponents often say your dad, Johnny Cash, wouldn’t be on board with your cause. What’s your line on that claim?

Cash: Oh, it’s so ridiculous, and I never use him to support my own agenda. But he was on the advisory board of PAX, the anti-gun-violence-against-children organization. So, come on. He had hunting rifles and antique Remingtons, but he didn’t have an arsenal of military weapons, and he never believed in that.

Kornhaber: Do you have anything else to say about the fact that country-music fans have been targeted twice in a very explicit way?

Cash: I wish they would take notice and start defending themselves by supporting more commonsense gun laws. Not by adding more guns to the mix.

For almost a year, the U.S. Olympic Committee has been struggling with the question of what is to be done about USA Gymnastics, the Olympic subsidiary accused of covering up decades of sexual abuse perpetrated by the sports doctor Larry Nassar. During a week-long sentencing hearing in January, 169 young women testified against Nassar, describing their assaults in wrenching detail. He was sentenced to a maximum of 175 years in prison.

After the hearing, the Olympic Committee fired the entire USAG board. Then USOC leadership overhauled the organization’s bylaws to increase the board’s accountability. A few months after that, they forced out the new CEO they hired in the wake of the Nassar allegations, after she became embroiled in a series of scandals of her own.

But on Monday, the USOC finally resorted to what gymnastics insiders are calling “the nuclear option”: The Olympic Committee is moving to decertify USAG, the organization that has overseen and financially supported gymnastics, one of the most popular Olympic events in America, since 1963. (If the decertification process goes smoothly, USAG will continue to exist as an umbrella organization for gymnastics clubs across the country—but without Olympic affiliation or funding, multiple sources told me, those clubs will probably stop paying for membership, and the organization will soon go bankrupt.)

“We believe the challenges facing the organization are simply more than it is capable of overcoming in its current form,” Sarah Hirshland, CEO of the USOC, wrote in an open letter to the U.S. gymnastics community. Instead of taking further steps to correct the toxic culture within USAG, which allowed a predator such as Nassar to cycle through dozens of victims undetected, the USOC has decided to get rid of the organization altogether.

[Read: Larry Nassar and the impulse to doubt female pain]

The #MeToo movement has sparked countless conversations about the culture of companies plagued by sexual harassment, particularly about how that atmosphere developed in the first place and how it can be fixed. Especially at the elite level, gymnastics creates an environment where it is easy for predators to take advantage of athletes, said Michelle Simpson Tuegel, the attorney representing several former gymnasts in a lawsuit against the USOC. Young girls practice, sometimes for weeks, at remote training facilities far away from their parents. And they are encouraged not to listen to their bodies, she told me, and are often praised for competing while injured.

Various leadership teams at corporations rife with sexual harassment have employed an array of strategies: Fire the alleged harassers, fire the CEO, hire a diversity and inclusion officer, and make commercials about the extent to which the culture has changed, then blast them across American TV networks. But the tactic that the USOC will likely employ—dissolve the problematic organization and make a new one—appears to be something of a new idea. And it’s not at all clear whether that tactic will work.

When the USOC announced its decision to decertify USAG, Nassar victims and other high-profile Olympic gymnasts praised the move. “THANK YOU,” tweeted Rachael Denhollander, one of the victims, after the announcement. “This is for every survivor.” The Olympic medalist Aly Raisman, who was also abused by Nassar, described the decertification as “a significant step forward that is necessary for the overall health and well-being of the sport and its athletes.”

[Read: Where Larry Nassar’s judge went wrong]

Still, the dissolution of one organization, and the possible creation of another, might not be enough to permanently change a culture of abuse that victims claim has existed within American Olympic gymnastics for more than 30 years. “Decertification is not going to overhaul the cultural problems inherent to the sport,” Simpson Tuegel told me. “The Olympic Committee will just be stamping a different name on the same thing.”

She suggested that the move might have something to do with the pile of lawsuits pending against both USA Gymnastics and the U.S. Olympic Committee, filed by former gymnasts who say they were sexually assaulted while on the U.S. Olympic team. “It seems awfully convenient that the announcement comes now, right as these lawsuits are really starting to move,” Simpson Tuegel said. “It really appears that USOC is trying to distance themselves from USAG.” USAG, not the USOC, has borne the brunt of the criticism for its handling of the Nassar case, so establishing some distance between the two organizations, she told me, could work in the USOC’s favor.

The decertification announcement was noticeably lacking in detail. Hirshland said there might be a new organization—one that “lives up to the expectations of the athletes and those that support them”—but did not describe how that organization would function. The question of whom it will employ, Simpson Tuegel told me, is on everyone’s mind: “Will these be all new people?” The USOC has not made any public statements about who might work for the next manifestation of USA Gymnastics. But because there are relatively few professional sports administrators who specialize in gymnastics on the national level, multiple people with knowledge of the situation told me, it’s likely that at least some portion of former USAG employees will transfer over. So then the question becomes, How many firings are required to create a blank slate?

Even if the USOC fired every one of USAG’s employees and hired a completely new staff, the process still wouldn’t necessarily prompt a culture change, said Catherine Mattice Zundel, a professional workplace-culture consultant. When she helps companies combat a culture of widespread sexual harassment, she said, her first step is to determine what stopped people from speaking up in the first place. If an HR representative looks the other way after hearing an allegation, she said, that doesn’t necessarily mean that particular person is the problem. Firing that employee, who is likely acting out of fear of backlash from people at the top, she told me, probably wouldn’t have a tangible impact on company culture.

When building the leadership team at the new organization, Zundel said, the USOC would need to conduct extensive training with new employees and watch closely for what she called “sexual-harassment risk factors”: a lack of diversity, a bunch of men at the top, and obscure reporting mechanisms. “It’s not enough to say, ‘We’re going to start a new company,’” Zundel told me. “The new company has to do things differently.” In the world of gymnastics specifically, Simpson Tuegel said, the leadership has to put the health and well-being of its young female athletes above competitive success.

“What would have happened to Uber if they’d tried to rebrand?” Zundel mused as we wrapped up our interview. In 2017, almost 500 former and current employees filed a lawsuit against the ride-sharing company over incidents of harassment and workplace discrimination. The wave of complaints, prompted first by a viral essay written by an Uber alumna named Susan Fowler, was a PR nightmare. But if Uber had shirked its old name and identity for a second incarnation of itself—the path that the USOC has proposed for USAG—Zundel wonders whether the company could ever have actually transformed, as it seems to be trying to do. “There is a value to owning up to something that went wrong,” she told me, “as yourself, not as someone else.”

Graphic novels aren’t just for kids or comics enthusiasts. The written word can evoke rich imagery, but in graphic storytelling, every aesthetic and narrative choice—from the colors used, to the spacing of each frame, to how and when dialogue is portrayed—can affect a reader’s experience.

In The Sculptor, Scott McCloud depicts the grandest of ideas (life, death, family, fame) in small, detailed frames, through the eyes of a young artist. For Tillie Walden (the Eisner Award–winning cartoonist) and Lisa Hanawalt (the artistic brain behind BoJack Horseman), the visual medium makes way for their stunning worlds focused on women who disrupt the science-fiction and Western genres, respectively. And while Jérôme Ruillier’s The Strange features anthropomorphic animals, the story it tells about the anxieties of being an undocumented immigrant is very much of this world.

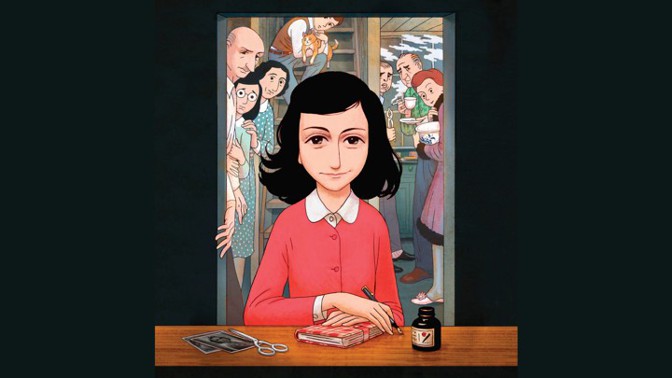

Sometimes, words are still the best medium. Seventy-one years after Anne Frank’s diary was first published, a new graphic adaptation visualizes Frank’s story for a new generation of readers, but what gets lost in the translation?

Each week in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas, and ask you for recommendations of what our list left out. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

What We’re Reading

The Quandary of Illustrating Anne Frank

“The book’s carefully crafted images interpret elements of Frank’s story with beauty and humor. But … the girl who breathed dimension into an unfathomable history is flattened, her power diluted.”

📚 ANNE FRANK’S DIARY: THE GRAPHIC ADAPTATION, adapted by Ari Folman and illustrated by David Polonsky

An Intergalactic Tale Populated by Women

“Walden has created a science-fiction universe that is about women, queer love, old buildings, and big trees. It may piss off science-fiction purists.”

📚 ON A SUNBEAM, by Tillie Walden

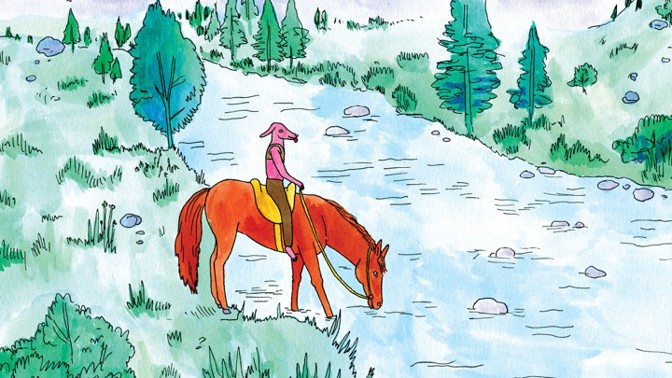

Coyote Doggirl Gives the Western a Whimsical, Watercolor Spin

“Hanawalt’s graphic novel respects its heroine’s restlessness. Her freedom, it seems to argue, is sacred.”

📚 COYOTE DOGGIRL, by Lisa Hanawalt

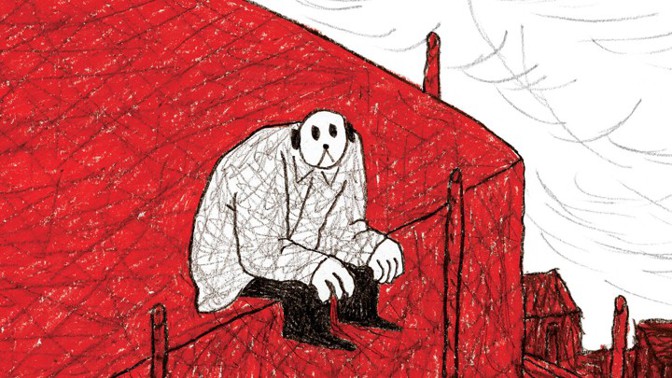

The Graphic Novel That Captures the Anxieties of Being Undocumented

“The protagonist is not a ‘stranger,’ with the opportunity to become known, or perhaps to even become a friend; he’s a ‘strange,’ and therefore always alien.”

📚 THE STRANGE, by Jérôme Ruillier

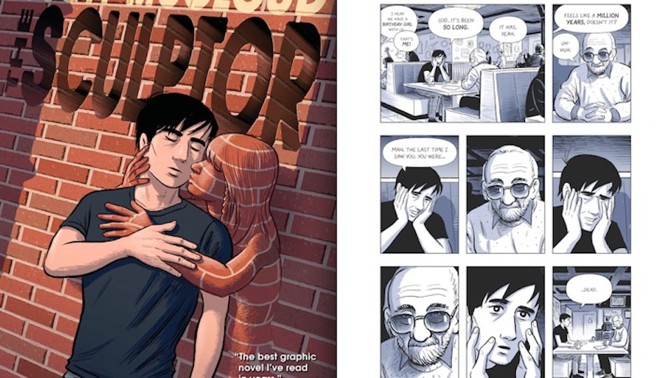

Scott McCloud’s The Sculptor Proves How Much Graphic Novels Can Do

“The story boils down to a magical dilemma about weighing the urge for a family down the road against the desire for professional validation today. Only this time—thanks to a deal with Death—it’s a man whose clock is ticking.”

📚 THE SCULPTOR, by Scott McCloud

You RecommendLast week, we asked you to share your favorite novels and stories centered on a specific place or location. Deborah Green, from Moose Pass, Alaska, said Willa Cather’s classic My Ántonia “brings the Plains alive in all its complexity; from searing heat to blizzard storms, [it’s] a land that gives abundantly and can also reduce a person to the most desperate straits.”

Kathleen Parks recommended Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid, a novel about refugees and migration. Kathleen recalled a scene set in the “hillsides overlooking San Francisco and Marin County” as “an alternative vision of serenity, where relieved immigrants create new homes in tents and shelters on the hills. I can never see the coastline without remembering that scene.”

What’s a graphic novel that you think everyone should read? Tweet at us with #TheAtlanticBooksBriefing, or fill out the form here.

This week’s newsletter is written by J. Clara Chan. The book on her bedside table right now is This Little Art, by Kate Briggs.

Comments, questions, typos? Email jchan@theatlantic.com.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

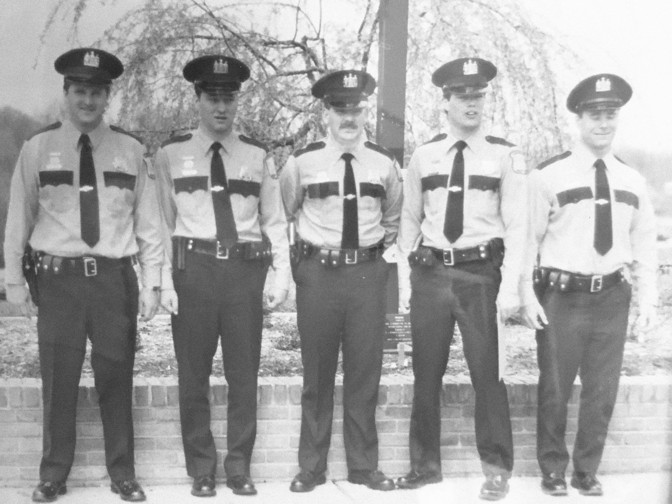

Kevin Simmers is a former police sergeant in Hagerstown, Maryland. During his tenure as a narcotics officer, he aggressively pursued drug arrests—especially those related to heroin. “I believed my entire life that incarceration was the answer to this drug war,” Simmers says in a new documentary from The Atlantic.

Then his 18-year-old daughter, Brooke, became addicted to opioids.

In the short film, Simmers shares the personal tragedy that led to a radical transformation in his ideology. “I did everything wrong here,” he admits. “I now think the whole drug war is total bullshit.”

Read Jeremy Raff’s article, “A Narcotics Officer Ends His War on Drugs,” for more.

Subscribe to Radio Atlantic: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Play

Executive Editor Matt Thompson interviews Atlantic reporters on what lessons they drew from the midterm elections, speaking in turn with: Vann Newkirk, Emma Green, Ron Brownstein, Adam Harris, and David Graham.

Links

- “The Democrats’ Deep-South Strategy Was a Winner After All”(Vann R. Newkirk II, November 8, 2018)

- ”Tuesday Showed the Drawbacks of Trump's Electoral Bargain” (Ronald Brownstein, November 7, 2018)

- “The Year of the Woman Still Leaves Women With Terrible Representation in Government” (Emma Green, November 7, 2018)

- “The Democrats Are Back, and Ready to Take On Trump” (David A. Graham, November 7, 2018)

- “America Is Divided by Education” (Adam Harris, November 7, 2018)

- “The Georgia Governor’s Race Has Brought Voter Suppression Into Full View” (Vann R. Newkirk II, November 6, 2018)

Robert Sherrill was an outsider by the nature of his work as a Washington correspondent for The Nation. A prolific anti-establishment voice, Sherrill was unafraid to play contrarian to the left or right of the aisle.

“He took the shibboleths of liberalism and exposed them as what he felt they were,” Ralph Nader told The Washington Post when Sherrill died in 2014. “He took liberals and progressives down a peg or two, or 10 pegs or two.”

But Sherrill was also an outsider for a more obvious reason: He was denied White House press credentials—and fought in the courts for a decade to obtain access in a case that has become an important precedent this week.

After receiving credentials to the House and Senate press galleries in 1965—a prerequisite for receiving White House credentials—Sherrill received a letter in 1966 from the U.S. Secret Service denying him access to the grounds. No explanation was given. When he asked why his request for credentials was rejected, the Secret Service replied, “We can’t tell you the reasons.”

Thinking that his writing got him in trouble, Sherrill did not try to appease the Johnson administration. His 1967 book, The Accidental President, and the book that followed in 1968, The Drugstore Liberal, were assaults on President Lyndon B. Johnson and Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, respectively. If he was being shut out for political reasons, so be it.

[Read: The president and the press]

In January 1972, when Sherrill reapplied for White House press credentials, he was again denied without explanation. That’s when the American Civil Liberties Union took his case to federal court. With the ACLU’s help, Sherrill sued the Secret Service for violating his First and Fifth Amendment rights.

By the time a D.C. circuit-court judge ruled in his case in 1977, it had been 11 years after his credentials were originally denied.

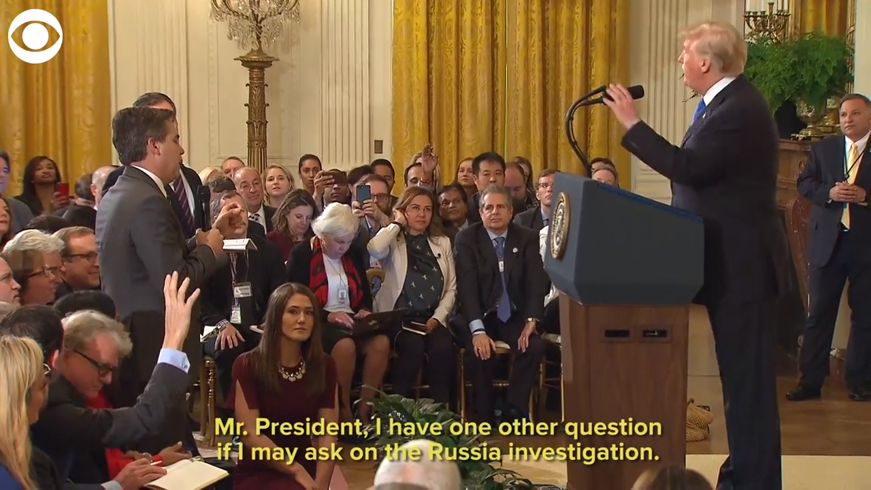

When Donald Trump clashed with Jim Acosta, the chief White House correspondent for CNN, at his post-midterms news conference on Wednesday—and later revoked his press credentials—he most likely knew nothing about the precedent set by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in Robert Sherrill’s case—precedent, experts said, that put the law squarely on Acosta’s side.

“Thank you Mr. President. I wanted to challenge you on one of the statements that you made on the tail end of the campaign in the midterms,” Acosta started, microphone in hand, staring ahead toward the president from the front row of the press conference.

Trump’s lips pursed and then released. “Here we go,” he said, practically breaking the fourth wall.

“If you don’t mind, Mr. President—” Acosta tried.

“C’mon, c’mon, let’s go.” The president let out a half whistle from his mouth and motioned to his rival to hurry up and ask his question.

“—that this caravan was an invasion.”

“I consider it to be an invasion,” Trump replied.

The exchange became testier and Trump’s complexion reddened. “Honestly, I think you should let me run the country. You run CNN. And if you did it well, your ratings would be better,” Trump told the reporter.

Acosta held on to the microphone as a White House intern tried to grab it back from him. “Mr. President, I had one other question, if I may ask, on the Russia investigation,” Acosta said. “Are you concerned that—”

Trump lifted a finger and wagged it from the podium. “I’m not concerned about anything about the Russia investigation, ’cause it’s a hoax.” He walked away from the podium momentarily, readying for his next hit. Acosta gave in and relinquished the mic.

“I’ll tell you what,” the president huffed. “CNN should be ashamed of itself, having you working for them. You are a rude, terrible person. You shouldn’t be working for CNN … You’re a very rude person. The way you treat Sarah Huckabee [Sanders] is horrible and the way you treat other people are horrible. You shouldn’t treat people that way.”

When Acosta returned to the White House grounds later that evening to do a live shot for Anderson Cooper 360°, the Secret Service asked for his hard pass, which he had held since 2013, and confiscated it. They were just following orders, and he understood that; the orders came from higher up. His access was revoked: He was locked out of the Trump White House.

To explain why Acosta’s credentials had been revoked, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, Trump’s press secretary, tweeted a highly edited video on Wednesday that appeared to show Acosta hitting the intern who tried to grab his microphone. Sanders wrote on Twitter, “President Trump believes in a free press and expects and welcomes tough questions of him and his administration. We will, however, never tolerate a reporter placing his hands on a young woman just trying to do her job as a White House intern...” Acosta tweeted back, “This is a lie.”

In actuality, the video Sanders shared was doctored and originally posted by Paul Joseph Watson, a British conspiracy theorist associated with the fake-news website Infowars.

[Read: Video doesn’t capture truth]

CNN immediately issued a strongly worded protest: “The White House announced tonight that it has revoked the press pass of CNN’s Chief White House Correspondent Jim Acosta,” the network’s statement read. “It was done in retaliation for his challenging questions at today’s press conference. In an explanation, Press Secretary Sarah Sanders lied. She provided fraudulent accusations and cited an incident that never happened. This unprecedented decision is a threat to democracy and the country deserves better. Jim Acosta has our full support.”

The decision to revoke Acosta’s credentials has led to condemnation from other journalists.

The White House Correspondents’ Association denounced “the Trump Administration’s decision to use US Secret Service security credentials as a tool to punish a reporter with whom it has a difficult relationship.” The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press wrote, “This is clearly inappropriate and unprecedented punishment by the Trump Administration for what it perceives as unfair coverage by the reporter, and White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders’ false description of the events leading up to it is insulting not only to the nation’s journalists, but to its people.”

Journalists and a number of politicians shared support for Acosta, some calling for solidarity on both sides of the aisle and among the press corps. “News the White House pulled Jim @Acosta’s credentials is not an attack on one journalist but all of the press,” the veteran journalist Dan Rather, formerly of CBS News, tweeted. “There should be complete solidarity. This is a moment for any Republican who says they believe in the Constitution to stand up.”

Many Republicans and conservative journalists did stand up for Acosta.

“The media is not the enemy of the people,” the former Florida Governor Jeb Bush tweeted. “The freedom of the press is protected by the Constitution. Presidents never enjoy pointed questions from the press, but President Trump should respect their right to ask them and respect Americans enough to answer them.”

The conservative blogger Erick Erickson tweeted, “Y’all, I’m sorry to defy the tribe, but I’ve watched this video over and over and it looks more like @Acosta had his arm out pointing with his finger and when she tried to pull the microphone down, both his arms went down rather naturally.”

Howie Kurtz, the host of Fox News’ Media Buzz, said that while he criticized Acosta’s behavior, “The [White House] escalation is just making him into a journalistic martyr.”

“No ref would throw flags for the physical altercation,” Ari Fleischer, a former White House press secretary under George W. Bush, said in an interview. “It wasn’t a physical altercation; it was incidental contact. No flags should be thrown.” Fleischer refused to defend Acosta’s behavior or blame the White House for its actions, but he agreed that this was not about Acosta assaulting anyone.

Among those in media and politics, the widespread consensus was an obvious one: This was not about safety and security; this was not about an assault. Acosta was punished for the way he went about his reporting.

[Read: How does Donald Trump think his war on the press will end?]

“The White House Correspondents Association, the White House, and CNN should be sitting down together and separately to address this,” Frank Sesno, the director of George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs, told me. Sesno is a former CNN Washington bureau chief and White House correspondent as well. “If there are professional concerns that the White House has about Jim Acosta or anyone else, they should express that professionally. They should be talking about that openly and there should be an effort to determine what, if anything, needs to change. The response is not engaging the Secret Service to pull someone’s credentials.”

“That’s just completely inappropriate and just this side of thuggery in my view,” Sesno added.

In public remarks on Friday morning, Trump seemed unremorseful about pulling Acosta’s credentials. The president threatened further punishment for reporters like American Urban Radio Networks’ April Ryan, calling her a “loser.”

“It could be others also” if they “don’t treat the White House and the office of the presidency with respect,” Trump said.

Sherrill never knew why the Secret Service had refused to issue him credentials; they wouldn’t tell him. Only in 1972 did White House counsel John Dean and John Warner, the assistant to the director of the Secret Service, inform the ACLU that “Sherrill had been denied accreditation ‘for reasons of security’ on May 3, 1966.”

The Secret Service cited two incidents that had little to do with the president’s safety or White House security: Sherrill had gotten into a physical altercation in 1964, while he was a political writer for the Miami Herald, when he punched the press secretary to Florida Governor C. Farris Bryant aboard a Johnson campaign train. (He was arrested and fined for physical assault.) Additionally, the Secret Service noted that Sherrill had been charged with assault in 1962 in Texas.

The D.C. circuit court ruled in Sherrill’s favor in 1977. While the court did not demand that the Secret Service issue him a press credential, it did set forth a series of new, transparent steps to ensure that no reporter’s First Amendment rights were violated.

“Once the government creates the kind of forum that it has created, like the White House briefing room, it can’t selectively include or exclude people on the basis of ideology or viewpoint,” said Ben Wizner, the director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project.

The new steps enunciated in the Sherrill decision to ensure that reporters’ First Amendment rights are not violated include the requirement to give the reporter notice and the right to rebut a formal written decision, which must accompany any revocation. “We further conclude that notice, opportunity to rebut, and a written decision are required because the denial of a pass potentially infringes upon First Amendment guarantees,” the court’s ruling states. “Such impairment of this interest cannot be permitted to occur in the absence of adequate procedural due process.”

“If the Secret Service makes this kind of determination that they’re going to no longer let someone have access, or limit access from the start, there should be a really good reason for that,” Michele Kimball, a media-law professor at George Washington University, said. “And if you are denied that access, there should be some sort of procedural due process for you, [so] that you can find out what happened. And it’s sort of that check to make sure that, again, it’s being handled evenhandedly.”

CNN declined to comment on Acosta’s situation. The network did not respond to questions about whether Acosta planned to sue or whether he is taking the steps put forth in Sherrill that allow him to object, rebut the decision, and seek written explanation from the Secret Service.

“What they’ve done here is not only unwise, but probably illegal,” the ACLU’s Wizner concluded.

In 1990, The Los Angeles Times profiled The Nation in its 125th year.

Sherrill had continued to cover the White House in the Carter and Reagan administrations, and he kept up his role writing about major corporations.

“Sherrill is the ultimate outsider, journalistically speaking, which makes him the quintessential Nation writer,” the Times wrote.

He clearly relished that role as an outsider, because when he won his 11-year battle with the White House to get credentialed, he opted against it.

“The fun thing about this was that when I was finally going to get a press pass, I never applied,” Sherrill told the Times. “I didn’t want to be in the White House. I had been in Washington long enough to realize that was the last place to waste your time sitting around for some dumb [expletive] to give a press conference.”

When all was said and done, Sherrill knew his best work would be done far away from the place he was never allowed to visit.

On Thursday night, Acosta’s name was part of a triple-byline story on CNN.com. “Trump considering [Chris] Christie, [Pam] Bondi, [Alexander] Acosta for attorney general,” he reported alongside Jeremy Diamond and Sarah Westwood.

“When they go low, we keep doing our jobs,” Acosta said on air Wednesday afternoon.

Acosta, like Sherrill, had shown that the White House could revoke his credentials, but it couldn’t stop him from doing his job.

Yesterday, tens of thousands of residents fled their homes in Paradise, California, north of Sacramento, escaping a fast-moving wildfire driven by high winds that swept through their community. Within 24 hours, the Camp Fire has burned more than 20,000 acres, and has virtually destroyed the town. Thousands of homes and other structures in Paradise have been consumed or badly damaged by the blaze. As firefighters struggle to gain control of the Camp Fire, several other wildfires are threatening other parts of the state, including the Woolsey Fire near Malibu, which has just prompted evacuation orders for some 13,000 residents.

Last week, Eliot A. Cohen used The Lord of the Rings to analyze a phenomenon he observed among the “erstwhile NeverTrumpers” who “attempt to cleanse themselves of the stain of having signed letters denouncing candidate Trump by praising President Trump’s achievements and his crudely framed, rough-hewn wisdom.” When power is corrupt, Cohen argued, there is no way to escape its toxic influence.

I’ve long felt that The Lord of the Rings was underappreciated for its analysis of morality, honor, and the traps that power sets for the unwary and the ambitious. You’re quite right to compare Ross Douthat to Saruman.

However, some conservatives have made a worse bargain than Saruman did. They’ve taken the equivalent of one of the Nine Rings of Power that Sauron handed out to Mortal Men. And in doing so, they’ve become hollowed-out shells. They’ve thrown honor, decency, and everything else that conservatives used to claim was important into the flames in order to grasp political power above what they could have gained on their own.

Kirstjen Nielsen strikes me as a prime example of a thoroughly modern Ringwraith. She’s given up her morality and perhaps her soul to hang on to her position as the head of the Department of Homeland Security.

Unfortunately, no wise and just philosopher-king is lurking in the wilds of America to set everything right. Aragorn isn’t coming to save the day with the banner of the Kings. We must do it ourselves, and it’s going to be hard, if not impossible. My son told me that he believes this to be the task that is set before his generation.

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

Nancy Ott

Pittsburgh, Pa.

Professor Cohen has hit the nail on the head. The Lord of the Rings story characterizes the struggle of men and women at any time in history who try to fight temptations of personal gain at the expense of personal values.

Tom Houser

Sheppton, Pa.

Eliot Cohen writes a clever and insightful article on the morality embodied in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and he does a good job of applying it to the modern American political landscape. But he applies that lens a bit narrowly when he applies it only to former NeverTrumpers now finding accommodation with our president. Would Democrats have reacted any differently had Hillary won the election and a subsequent investigation turned up credible evidence of malfeasance on the part of her and her team? At the conclusion of The Lord of the Rings, it is not Frodo’s resolution or courage that saves Middle Earth (he cannot bring himself to destroy the Ring), but only his pity for Gollum. That’s a lesson Democrats would be well served to remember.

Daniel H. Smith

Highlands Ranch, Colo.

Eliot Cohen likens Ross Douthat to Saruman, who in The Lord of the Rings made a pitch to the good men of Middle Earth to recognize that Mordor’s time has come, and that they would do well to ally with it. They may even, according to Saruman, come to direct Mordor’s decisions.

It was a trap, of course. Cohen says a recent Douthat column about NeverTrumpers put him in mind of Saruman’s trap.

That is a deeply unfair characterization. I urge you to read the entire column. Douthat has never hidden his contempt for Trump. But he is trying to be what NeverTrumpers like the establishmentarian Eliot Cohen are not: realistic. In his column, Douthat recognizes that whether we like it or not, Trump has changed what it means to be politically conservative in America.

Rod Dreher

Excerpt from a blog post on theamericanconservative.com

Excellent piece. This is a perfect example of why the study of literature continues to be a critical component of a solid education. Despite our current focus on STEM education, it’s literature that gives us insight into how to understand human nature, politics, law, and culture.

Mary Vreeland

Fredericksburg, Va.

Andrew Parker wrote: Lord of the Rings is an allegory for the rise of fascism. This author’s metaphor is very germane.

Jary May Blige wrote: “The stakes are not nearly as high for conservative thinkers as they were for the inhabitants of Middle Earth.” Ehm, not so sure about this.

While I’ve been reading THE LORD OF THE RINGS aloud to my kids, I’m also reading @flemingrut’s magisterial commentary alongside; @EliotACohen’s in the same vein, letting Gandalf speak clearly & forcefully against any moral shortcut & excusehttps://t.co/C26qTD426G#LOTR #Tolkien

— Josh Hale (@expatminister) November 5, 2018Fwiw I think NeverTrumpers who want to resist Trump himself but see something of use or importance or necessity in populism are closer to Boromir than Saruman:https://t.co/Ol9mtB4Za3

— Ross Douthat (@DouthatNYT) November 1, 2018I think the important insight we can take from this piece is that the Presidency and, by extension, the whole of the Federal government and bureaucracy, is the One Ring, which must be cast into the fire and eternally destroyed. https://t.co/EJHs5mb0Bn

— Fr. Brendon Laroche (@padrebrendon) November 1, 2018Eliot A. Cohen replies:I appreciate the kind words about “The Saruman Trap.” The Lord of Rings is indeed a modern epic, but we should allow writers a bit of room for whimsy—having a bit of fun while making a serious point. Because it is an epic, LOTR addresses universal themes, and, Democrats being human, I quite agree that they are as subject to temptations of power as Republicans. But it is the latter who are in charge now. As for Rod Dreher, he uses the word establishmentarian in the way Douthat uses the words apostate and convert, i.e., as a way of reading out of a community those whose ideas he does not accept by using a label in place of an argument. I dislike that. I also reject the notion that “Trump has changed what it means to be politically conservative in America.” Just because the Republicans have abandoned conservatism does not mean that I have to. Like an Ent, I don’t change.

The past few months have been busy for the student activists of March for Our Lives, an advocacy group founded after a gunman killed 17 people at a Parkland, Florida, high school earlier this year. In anticipation of the midterm elections, organizers toured the country encouraging young people to vote for candidates who support stricter gun-control laws. That didn’t quite pan out exactly the way they had hoped on Tuesday night, as their favored Senate and gubernatorial candidates in Florida didn’t win outright, and those elections are currently still being contested.

And then two days after the election, they woke up to yet another mass shooting, as at least 13 people were gunned down during college night at the Borderline Bar and Grill in Thousand Oaks, California, which was frequented by students from the nearby Pepperdine University, California Lutheran College, and California State University Channel Islands.

[Read: A mass shooting in one of the “safest cities in America”]

Matt Deitsch, the older brother of two Parkland survivors and a member of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School class of 2016, is the chief strategist for and one of the founders of March for Our Lives. He spoke with me on Thursday about what happened in Thousand Oaks, the push March for Our Lives has been making for stricter gun control, and how the group plans on responding to the latest shooting.

Natalie Escobar: I want to start off by acknowledging that today must be hard. Could tell me about what’s on your mind?

Matt Deitsch: I had a thought of being back to those horrific moments [right after I learned about the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas]. I also thought about how before the midterm elections, politicians were talking about things that weren’t really a threat to American citizens [instead of talking about gun violence], and now after the election, mass shooters are still in the headlines. We’ve had over 300 this year, and it’s not going to slow down until we do something about it. I think now we have a Congress that will at least potentially take the conversation beyond where it’s stalled for so long.

Escobar: Reportedly, two of the people at the bar last night were there celebrating their 21st birthday—that detail hit a lot of us in the newsroom pretty hard. It’s supposed to be a milestone of adulthood, and I’m wondering if you think that how young people feel about coming of age has changed at all in a time when events like this keep happening.

Deitsch: We understand that we have a long life ahead of us, and we don’t want to live a long life in fear. And so we’re going to do something to stop this horror. I turned 21 last month. We hear about all the young people with so much potential gunned down, and we have to stop it, because the future is suffering and our youth are traumatized.

Escobar: March for Our Lives has recently been focused on the midterms and getting young people to the polls. What was your Election Day like? Can you tell me about the things you were doing in the hours before results came in?

Deitsch: A week and a half before the election, we did a tour of 25 colleges around the country. We came to Parkland for Election Day, and we created a “war room” with local students. In the war room, we set up a phone bank and called 18-to-21-year-olds across the state of Florida, and we made over 9,000 phone calls in one day. Then we went to a viewing party at night. The Florida numbers weren’t surprising, but it definitely reminded us where we are in Florida. The youth turnout was the highest it has ever been in American history, so it’s a huge step in the right direction.

Escobar: Are the election results going to change your strategy at all? What are you planning next?

Deitsch: Our organization has never really been candidate-centric or policy-centric. We hope to expand the electorate of the people who care about this issue, and understand the urgency of putting this issue first. We’re going to keep doing what we’re doing and create a blueprint for young people to have more of a force in the electoral process. Elected officials now know that they’re going to need young people to win these close races.

Escobar: I’m wondering what you observed in your Parkland community on the night of the election and if you’ve seen people change since February.

Deitsch: There’s a reason it takes you three times voting to become a lifetime voter, because you understand the wins and the losses and what’s necessary to be a part of the system, to feel your own power. I think Parkland is starting to see its own power. I felt really hopeful, and there’s so much to celebrate.

David Mackenzie is a great Scottish director who hasn’t really made a film set in Scotland in years. In 2003, he emerged with Young Adam (starring Ewan McGregor), a moody yarn set in 1950s Glasgow, but since then has only occasionally revisited his native land. His most recent films—the English prison drama Starred Up and the Texas bank-robber thriller Hell or High Water—were some of his best. But with Outlaw King, Mackenzie returns to his homeland to tackle one of its biggest legends: Scotland’s medieval battle for independence. It’s a tale that’s been covered before, most notably by Mel Gibson’s Oscar-winning hit Braveheart.

Outlaw King has a star of its own—Chris Pine, in the role of King Robert the Bruce. Robert was portrayed in Braveheart as a calculating but gutless politician who ultimately abandons the rebellious cause of William Wallace (Gibson). Outlaw King chronicles what happened afterward, as Robert takes up the mantle of Scottish independence in the early 14th century and begins a guerrilla campaign against the English King Edward I (Stephen Dillane). The film is intent on dashing the romantic myths of Gibson’s movie and many other medieval dramas, laying bare the grimy truth of period warfare.

What was that truth? A lot of men charging at one another in fields, whacking folks off their horses with swords and halberds, and mud—lots and lots of mud. Robert was a noted tactician, and Mackenzie wants to dramatize that, though the king’s idea of tactics mostly involves baiting English soldiers to charge into slimy pits littered with spikes. As innovative as Robert was, he still lived during the early 1300s, and Outlaw King is caked with the grubby details of that time. The film may be too much of a bloody slog for some; others will be on board for every gruesome minute, as I was.