Todo mundo sabe que Bolsonaro tem concepções toscas e rudimentares sobre assuntos sensíveis como o homossexualidade, a violência, a esquerda e a liberdade de imprensa. A julgar pelas últimas façanhas do presidente eleito, o Planalto não vai estancar sua verve autoritária.

O capitão tentou impedir que jornalistas entrassem no plenário do Congresso na comemoração aos 30 anos da Constituição Federal, trocou os pés pelas mãos em temas de política externa e anunciou, como um cacique arteiro, o fim do Ministério do Trabalho.

Também deu a luz ao Superministério da Justiça e da Segurança Pública, trazendo para a barra de sua saia o juiz que condenou, prendeu e tirou Lula da corrida eleitoral.

De qualquer forma alçado à condição de herói nacional pelo que fez na Lava Jato, Sérgio Moro, prestes a debutar na política depois de negar sua pretensão em pelo menos sete oportunidades, pode ser um muro de contenção aos disparates do novo governo. Para isso, precisa colocar em prática medidas do livro que empunhava durante o voo que o levou ao Rio de Janeiro para selar a sua indicação ao Ministério da Justiça.

A cartilha “Novas medidas contra a corrupção”, de iniciativa do portal Transparência Internacional e da Fundação Getulio Vargas, contém 70 proposições divididas em 12 blocos. Algumas delas, destacadas abaixo, parecem mais sensíveis à futura atuação do Sérgio Moro como ministro da Justiça. Se conseguir implementá-las apesar do ambiente em que ele próprio, Moro, foi gestado, já teremos algum avanço.

Capa do livro “Novas medidas contra a corrupção”, da Fundação Getúlio Vargas e da Transparência Internacional.

Imagem: Reprodução/FGV

Como é hoje: uma lei de 1965 regulamenta a matéria, mas possui baixíssima eficácia. Prevê, dentre outras sanções, pena de dez dias a seis meses de detenção. É comum que os crimes apurados de acordo com essa lei prescrevam.

O que propõe a cartilha: estabelece a responsabilização de agentes públicos que cometem atos de excesso de poder ou desvio de finalidade. Prevê como possíveis sanções, além da prisão e multa, o dever de indenizar o dano causado pelo crime, a perda do cargo, mandato ou função pública, a inabilitação para o exercício de cargo, mandato ou função pública por prazo de um a cinco anos, e penas restritivas de direito, incluindo a suspensão do exercício do cargo, mandato ou função pública e a proibição de exercer função de natureza policial ou militar em prazo de um a três anos.

Medida 25: Extinção da aposentadoria compulsória como penaComo é hoje: as Leis Orgânicas da Magistratura Nacional e do Ministério Público da União e dos Estados preveem a aposentadoria compulsória como uma das punições aos seus membros por infrações funcionais. Na prática, isso significa que, por exemplo, o juiz ou promotor de Justiça que cometer ato de corrupção pode ser aposentado e continuar recebendo remuneração.

O que propõe a cartilha: elimina a hipótese da aposentadoria compulsória como sanção e confere maior celeridade aos processos que investigam e punem membros do Judiciário e do Ministério Público.

Medida 26: Unificação do regime disciplinar do MPComo é hoje: o Ministério Público foi um dos grandes protagonistas nas operações que, nos últimos anos, trouxeram à tona casos escandalosos de corrupção nacional. Mas há gente que reclama que seus poderes não conhecem barreiras e que precisam ser limitados para que não haja excessos.

O que propõe a cartilha: cria um regime disciplinar para o Ministério Público, prevendo condutas irregulares, sanções cabíveis e regras do processo administrativo disciplinar a ser seguidas.

Medida 29: Transparência na seleção de ministros do STFComo é hoje: de acordo com a Constituição, o Supremo Tribunal Federal possui 11 Ministros, escolhidos entre cidadãos com mais de 35 e menos de 65 anos de idade, de “notável saber jurídico e reputação ilibada”. Depois de sabatinados e aprovados pela maioria absoluta do Senado, eles são nomeados pelo presidente da República.

O que propõe a cartilha: confere maior transparência ao processo de seleção de ministros do STF e impõe uma quarentena prévia, vedando a indicação de ocupantes de determinados cargos para a Suprema Corte, e posterior, proibindo que ministros concorram a cargos eletivos no prazo de quatro anos após saírem do tribunal.

Medida 41: Regulamentação do LobbyComo é hoje: a prática do lobby é uma realidade inegável, mas sua imagem é negativa. No cenário obscuro e malvisto das relações entre governo e iniciativa privada, o lobista é geralmente associado a alguém que se aproxima do Estado para corromper os agentes políticos e agir por baixo dos panos.

O que propõe a cartilha: a regulamentação profissional do lobby para conferir a maior transparência e mecanismos adicionais de controle social. A proposta busca ainda oferecer maior equilíbrio nas interações de diferentes interesses econômicos e sociais com autoridades públicas.

——

Na concepção dos seus idealizadores, as Novas medidas constituem uma política de Estado pautada em abordagem técnica. Ataca em frentes simultâneas e conta com a participação da sociedade civil para fomentar a atividade legislativa anticorrupção. É uma agenda pela qual o país anseia e da qual necessita.

Mas Bolsonaro já dá sinais de que se arrependeu de ter dado carta branca a Moro. Conforme o Valor Econômico, ele se antecipou e já puxou as rédeas do juiz, colocando o General Heleno Pereira, militar da reserva de su confiança, no comando do Gabinete de Segurança Institucional, que agora coordena os serviços de inteligência da Polícia Federal. Além disso, manteve a Controladoria-Geral da União como pasta separada da Justiça.

Sérgio Moro está pisando em ovos. Ele já não está mais no silêncio de seu gabinete, a sós com sua consciência jurídica. Sua metamorfose – de juiz herói da nação a político de um governo de extrema-direita – vai cobrar a conta.

Quando isso acontecer, o superministro precisará mostrar ao Brasil a que veio. Mesmo com a sombra do coronel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra à espreita.

The post Torça para que Moro siga o livro que levou à casa de Bolsonaro appeared first on The Intercept.

Richard Ojeda is running for president. Ojeda, a West Virginia state senator and retired U.S. Army major, lost his congressional bid in the state’s 3rd District on Tuesday, but saw the largest swing of Trump voters toward Democrats in any district around the country — overperforming 2016 by more than 35 points. Still, in a district that Donald Trump carried by 49 points, Ojeda, who rose to prominence because of his support for a teachers strike in West Virginia, lost by 12 points.

Ojeda’s case for his candidacy is straightforward: The Democratic Party has gotten away from its roots, and he has a unique ability to win over a white, black, and brown working-class coalition by arguing from a place of authority that Trump is a populist fraud. He’s launching his campaign with an anti-corruption focus that draws a contrast with Trump’s inability to “drain the swamp.”

His authority — and one of his greatest liabilities — would come, in part, from his own previous support of Trump in the 2016 general election. After backing Sen. Bernie Sanders in the primary, Ojeda refused to support Hillary Clinton, seeing her as an embodiment of the party’s drift toward the elite.

“The Democratic Party is supposed to be the party that fights for the working class, and that’s exactly what I do.”“I have been a Democrat ever since I registered to vote, and I’ll stay a Democrat, but that’s because of what the Democratic Party was supposed to be,” he told The Intercept. “The reason why the Democratic Party fell from grace is because they become nothing more than elitist. That was it. Goldman Sachs, that’s who they were. The Democratic Party is supposed to be the party that fights for the working class, and that’s exactly what I do. I will stand with unions wholeheartedly, and that’s the problem: the Democratic Party wants to say that, but their actions do not mirror that.”

Ojeda turned on Trump early in his term, concluding that the president’s interest in improving the lives of working people like those Ojeda grew up with in West Virginia, or served with in the military, was fake. Now, he wants to break the spell Trump still holds on half the country.

“We have a person that has come down to areas like Appalachia and has tried…and has convinced these people that he is for them, when in reality the people that he has convinced couldn’t even afford to play one round of golf on his fancy country club,” Ojeda said.

As a state senator, Ojeda led a push to legalize medical marijuana and played a central role in this year’s teacher walkouts that resulted in a rare pay increase for educators. In his congressional race, he ran on a thoroughly pro-labor, progressive platform, despite the partisan lean of the district, framing issues as pitting people against corrupt, out-of-touch elites. He focused heavily on the role of Big Pharma in sparking the opioid epidemic.

His energetic campaign style and pull-no-punches approach made him the focus of national attention during his congressional run. His announcement that he will run for president, which is first being reported by The Intercept, makes him one of the first Democrats to formally declare their intentions for 2020. Moves are being made early this year. As The Intercept reported over the summer, former Obama administration official Julián Castro floated a run as early as last summer, and there are already close to a dozen people considered likely to join him on the trail, including Sanders; Sens. Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Jeff Merkley; and former Vice President Joe Biden. A handful of billionaires, including Michael Bloomberg, have also floated the possibility.

Ojeda made his decision to run after surveying the field of potential presidential contenders and concluding that none of them would be able to stand up to Trump in the way that he could and draw the contrast that’s needed. “We’re going to have quite a few lifetime politicians that are going to throw their hat in the ring, but I guarantee you there’s going to be a hell of a lot more of them than there are people like myself — that is, a working-class person that basically can relate to the people on the ground, the people that are actually struggling,” he said. “I’m not trying to throw stones at people that are rich, but once again, we will have a field that will be full of millionaires and, I’m sure, a few billionaires.”

Speculation in Washington has begun to focus on the possibility that the ultimate Democratic nominee for president is not someone currently being discussed as a frontrunner. A recent poll found “none of the above” topped the list of presumed candidates.

Ojeda was backed in his House bid by the People’s House Project, a political action committee run by former congressional candidate and MSNBC host Krystal Ball. She’s supporting his presidential run, but acknowledged in an interview that he’s an unusual candidate for today’s Democratic Party. “I think the biggest challenge for Richard is whether or not people actually want real change. Whether they actually want a nation. Or if they’d prefer to just keep their tribes and their grievances,” she said.

Ojeda said he has never been to Iowa or New Hampshire — the states whose caucus and primary, respectively, formally kick off election season — but plans to make trips to both soon. As he prepares to campaign, Ojeda, who first assumed political office in 2016, will likely have to grapple with multiple immediate objections to his candidacy, even beyond his vote for Trump: political experience, identity, and his ties to coal country among them.

The Democratic Party’s coalition is fueled by women and an increasingly diverse base. When I asked if a white man from West Virginia could understand what was behind the Black Lives Matter movement, he argued that his experience living in and among the working class — which is heavily made up of black and Hispanic people — gives him insight into that struggle. “I can understand it far better than the millionaires and billionaires sitting around the conference tables in Washington, D.C. That’s a fact. Guess what? I’ve worked side by side with those people; I’ve served in the military with the people that lived in those communities,” he said. “I know far more about that life than [elites in Washington] know about that life. So when someone stands up that has a bank account that’s got $50 or $60 million in it, I personally could care less what they have to say about how they’re gonna … how they know what a single parent who is trying to put food on the table feels. Because they don’t.”

His identity, meanwhile, is not so simple. While both his grandparents worked in the West Virginia mines, as is common in the state, one of them immigrated illegally from Mexico to do so. One of his grandparents, after fighting in World World II, died in a mining accident. The Spanish pronunciation of the last name — “O-Hayda” — was tricky for people in the region, and it has evolved to “O-Jeddah.” Ojeda’s father, meanwhile, did not follow the career path into the mines, instead becoming a certified registered nurse anesthetist.

His lack of political experience, he said, should not be mistaken for a lack of organizational leadership experience. While he enlisted in the Army as a private out of high school, he said, he rose through the ranks to oversee a vast operation. “When I started in the military, I started as a private, the lowest rank you could possibly go, but I was also the chief of operations for the 20th Airborne engineers in Iraq, where we were in control of over 7,000 engineers. And every single operation that went on throughout the entire country of Iraq went through my JOC, and I was the chief of operations,” he said. The military helped put Ojeda through college and graduate school, and he now uses his experience overseas to argue against militarism and in favor of a diplomatic approach.

Another objection to his long-shot bid could come from the environmental community, which may worry that his advocacy for coal miners, and his roots in Logan County, West Virginia, would mean that he would push a fossil fuel dependent energy economy. Ojeda said that wouldn’t be the case, but he did note that he sees a limited use for metallurgical coal — which is mined in West Virginia — in the production of steel.

“If we can bail out the banks, there’s no reason we can’t create opportunity for the people who brought light to this country.”“I think it’s time for us to stop lying. Coal, in terms of energy, is gonna be overtaken; [natural] gas can do just as much far cheaper — it’s not gonna come back the way it was,” he said. “In terms of things like coal production, I just want to bring something to be able to replace, to give them an option. The fault lies in the leadership of the past; coal operators never wanted anything to challenge them. The truth is, we’ve got to offer these people options so they can transition to other jobs, and it can’t be minimum wage jobs. … If we can bail out the banks, there’s no reason we can’t create opportunity for the people who brought light to this country.”

His campaign will roll out a climate and environment plank soon, he said, but he wants to launch his campaign with a focus on lobbying and corruption in Washington, which he sees as a major obstacle to progress. To that end, he’s proposing an atypical suite of policy solutions: Members of Congress, he proposes, should be required to donate their net wealth above a certain threshold — Ojeda puts it at a million dollars — to discourage using public office for private gain. In return, retired members of Congress would get a pension of $130,000 a year and be able to earn additional income to reach $250,000. Anything above that would be donated.

“When you get into politics, that’s supposed to be a life of service, but that’s not what it’s been. You know, a person goes into politics, they win a seat in Congress or the Senate, and it’s a $174,000 [salary], but yet two years later, they’re worth $30 million, and that’s one of the problems that we have in society today. That’s how come no one trusts — or has very much respect for — politicians,” he said.

The notion of sacrificing for public service may seem radical, but it’s anything but that for millions of people in the military, said Ojeda. “Our servicemen that are in the military right now, staff sergeants in the United States Army out there in harm’s way, qualify for food stamps, but they truly live a life of selfless service,” he said. “Where I come from, the average family income is $44,000. So to me, this right here is something that everybody can relate to. We’re sick and tired of watching people that say that they’re going to fight for the people and run for office, but in reality they get in there and all they do is increase their wealth and power.”

He plans to pair that with other provocative ideas, such as requiring lobbyists to wear body cameras.

Ojeda, in positioning himself against Trump, is meeting right-wing populism with a left-wing variety. He uses language that is as direct as Trump’s, but unlike the president, he targets the nation’s elites, rather than vilifying vulnerable communities.

“The filthy rich convinced the dirt poor [that] the filthy rich are the ones who care,” he said. “We need someone in Washington, D.C., who’s going to be a voice for these people.”

Ryan Grim is the author of the forthcoming book, We’ve Got People: Resistance and Rebellion, From Jim Crow to Donald Trump. Sign up here to get an email when it is published.

Update: November 12, 2018

A previous headline on this story stated that Richard Ojeda led the West Virginia teachers strike. The headline has been clarified to reflect the fact that he played a key role in the strike but it was led by the state’s public school teachers.

The post Richard Ojeda, West Virginia Lawmaker Who Backed Teachers Strikes, Will Run for President appeared first on The Intercept.

Why, exactly, did Donald Trump not join Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, and Justin Trudeau at Saturday’s commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the original Armistice Day? I don’t know, and I don’t think anyone outside the White House does at this point.

What I do know is that one hypothesis that has shown up in many stories about his no-show—that Marine One, the presidential helicopter, “can’t fly” in the rain—doesn’t make sense.

As you’re looking for explanations, you can dismiss this one. Helicopters can fly just fine in the rain, and in conditions way worse than prevailed in Paris on November 10.

First, about helicopters and weather. (What follows is based on my having held an instrument rating as an airplane pilot for the past 20 years, and having worked in the Carter-era White House and occasionally having been aboard the Marine One of that era.)

There is nothing special about the rain-worthiness of the helicopter any president normally uses. In principle, any helicopter can fly in clouds or rain. The complications would be:

Icing: This is one of the big weather-related perils of flying. (The other is thunderstorms.) If (a) an aircraft is inside the clouds, and (b) the temperature is at freezing or below (down to about -15°C or -20°C, when it becomes so cold that the water behaves differently), there's a risk of icing: ice piling up on the wings, control surfaces, etc. This changes the shape of the airfoils, and it essentially makes a plane unable to fly. This was part of the story of the commuter plane that crashed going into Buffalo a few years ago. I did a long illustrated post about what icing looks like, and how it kills, back in 2011. Other posts are here and here.

But this only happens if a plane or helicopter is actually in the clouds (“visible moisture” is one of the requirements), and for a helicopter that, in turn, would mean a ceiling so low that a helicopter could not fly beneath it, clear of the clouds. Or, it could occur if the temperature profile were such that you get “freezing rain”—rain falling through a super-cooled atmospheric layer and being at or below 0°C when it hits, thus instantly freezing on whatever surface it touches.

Extremely low ceiling: If the ground were essentially fog-covered, so the pilot couldn't judge when he was about to touch down, that could be too dangerous to fly in. Think London pea-soup fog, or a bad day in Beijing.

So: Helicopters cannot safely fly inside the clouds when it's below freezing, and they can't safely or prudently land when there is dense fog or other very low-ceiling circumstances. And they cannot fly safely if it's extremely windy and gusty—which can make it dangerous to land.

Otherwise just about any helicopter can fly in rain, bad weather, etc.

From photos of Paris and the commemoration site Saturday, it didn’t appear that the ceiling was so low (or the temperature so cold) that icing would be a real factor. So just now I have dug up the archived “METARS”—the aviation-related weather reports—for Saturday at Orly airport in Paris, the closest reporting station to where Donald Trump was. Here’s the raw data for Saturday’s Orly METARs, at half-hour intervals essentially from dawn to dusk:

|

SA |

10/11/2018 17:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101730Z 20010KT 9999 BKN012 12/10 Q1002 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 17:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101700Z 20011KT 160V220 9999 BKN012 13/11 Q1002 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 16:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101630Z 20010KT 9999 BKN011 13/11 Q1002 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 16:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101600Z 20010KT 9999 BKN011 13/11 Q1002 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 15:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101530Z 23007KT 190V260 9999 BKN010 13/11 Q1001 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 15:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101500Z 20010KT 9999 BKN010 13/11 Q1001 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 14:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101430Z 20010KT 170V230 7000 -RA BKN010 13/11 Q1001 TEMPO 2500 RA BKN006= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 14:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101400Z NIL= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 13:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101330Z 21010KT 170V250 9999 -RA BKN011 12/11 Q1001 TEMPO 2500 RA BKN006= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 13:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101300Z 21009KT 180V250 9999 -RA BKN010 12/11 Q1001 TEMPO 2500 RA BKN006= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 12:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101230Z 25010KT 7000 -RA BKN010 12/11 Q1001 TEMPO 2500 RA BKN006= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 12:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101200Z 19012KT 9999 -RA BKN009 12/11 Q1001 TEMPO 2500 RA BKN006= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 11:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101130Z 20011KT 3000 -RA BR BKN006 OVC013 12/11 Q1001 TEMPO 2500 RA BKN006= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 11:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101100Z 19011KT 2700 -RA BR OVC006 11/11 Q1002 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 10:30-> |

METAR LFPO 101030Z NIL= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 10:00-> |

METAR LFPO 101000Z 18011KT 6000 RA BKN008 11/10 Q1002 NOSIG= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 09:30-> |

METAR LFPO 100930Z 19011KT 7000 RA BKN010 11/10 Q1002 TEMPO 4000 RA BKN009= |

|

SA |

10/11/2018 09:00-> |

METAR LFPO 100900Z 18010KT 9999 -RA BKN010 11/10 Q1002 TEMPO 4000 RA BKN009= |

I am not going to bother to decode this all. (Being able to read METARs is part of ground school in the learning-to-fly process.) But here are the essentials:

On Saturday morning, the weather in Paris was rainy and overcast—bad weather, but not any exceptional aeronautical challenge. The worst conditions during the day in Paris were at noon, when there was an overcast ceiling of 600 feet. (“101100Z 19011KT 2700 -RA BR OVC006”. The -RA means “light rain.” The BR means “mist,” and the mnemonic for remembering it is “Baby Rain.”) As a benchmark: To get an instrument rating, whether in an airplane or a helicopter, you have to show the ability to fly an approach “to minimums,” which (depending on the airport and the approach system) can be as low as 200 to 300 feet. Still, on Saturday morning, a helicopter trip from Paris would probably have meant spending part of the time in the clouds. The temperature in Paris through the morning was 11 to 12 degrees Centigrade, or the low 50s Fahrenheit. That is not very cold. The normal “lapse rate” for air temperature is about 2 degrees Centigrade colder for each thousand feet you go up. In normal circumstances, that would mean that the freezing level was at an elevation of around 6,000 feet. (To spell it out: 12°C at ground level, minus 2 for each thousand feet, means that you reach 0°C around 6,000 feet up.) So at an altitude of 3,000 or 4,000 feet this would not be an icing-peril scenario. It was not very windy. Through the morning the wind was reported at 11 or 12 knots—not enough to worry about.Of course, safety considerations are different when a president is traveling. The pilots and maintenance practices of Marine One are presumably the best that can be found, but the play-it-safe factor when carrying a president has to be larger than for other missions. So who knows whether some aviation official really said: Sorry, this is no-go.

But precisely because of those cautions and complexities, any known-universe past presidential travel plan would have a bad-weather option, or several of those, already lined up. This is the way it has worked in any White House I've been aware of.

Why didn’t an American president go to a once-in-a-lifetime ceremony? Might it have been a still-undisclosed security threat? Something else that Donald Trump had to do?

I don’t know. I do know that whatever the obstacle was, it wasn’t that “helicopters can’t fly in the clouds and rain.”

‘Camp Fire’: “Forest fires might be seen as the particularly horrific edge of a sword that is coming for us all,” writes Robinson Meyer on the two massive wildfires—the Camp and Woolsey fires—that have devastated communities in both the northern and southern parts of California. These conditions suggest the worst is yet to come.

On Veterans Day: President Donald Trump’s Paris visit over the weekend, and what he chose to say and do—or not—on the 100th anniversary of the end to the fighting in World War I, has underscored to European leaders like Emmanuel Macron of France that the U.S. administration’s “America First” message means just that. What else we’re thinking about on Veterans Day: Read our November 2017 series featuring perspectives from veterans on issues from universal health care to women in military service to how PTSD impacts children.

Birthright: What happens when a nation limits birthright citizenship? This Caribbean country offers a lesson on what follows, writes Jonathan M. Katz.

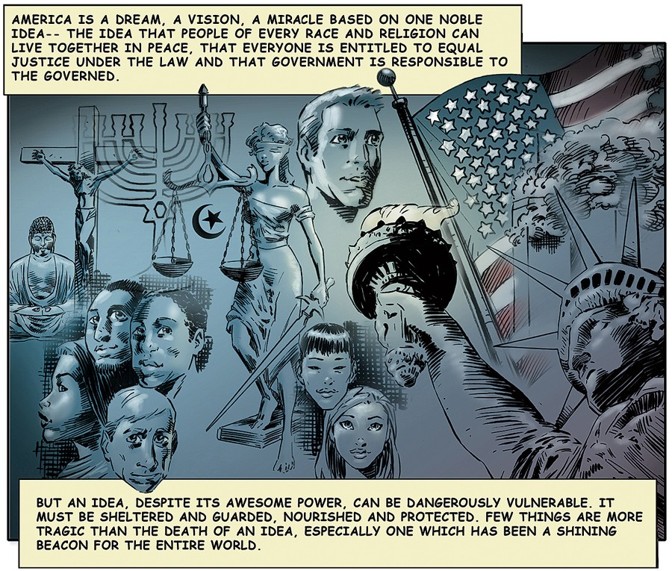

Snapshot "America is a dream, a vision, a miracle based on one noble idea," Stan Lee wrote in a piece—illustrated in the above panel by Anthony Winn—for The Atlantic's 150th anniversary issue in November 2007. "But an idea, despite its awesome power, can be dangerously vulnerable." See the full piece here. Lee, whose name has become synonymous with the American superhero comic, died Monday at age 95.Evening Read

"America is a dream, a vision, a miracle based on one noble idea," Stan Lee wrote in a piece—illustrated in the above panel by Anthony Winn—for The Atlantic's 150th anniversary issue in November 2007. "But an idea, despite its awesome power, can be dangerously vulnerable." See the full piece here. Lee, whose name has become synonymous with the American superhero comic, died Monday at age 95.Evening ReadIn 2000, Florida gave us a recount that ended with the Supreme Court showdown Bush v. Gore. But a more instructive moment to look to as the state begins historic recounts might instead be this 1985 Congressional race in Indiana, writes the historian Julian E. Zelizer:

Arguably, the Bloody Eighth is what led to the eventual GOP takeover of the House, under Newt Gingrich, in 1994. The Bloody Eighth was his trial run, and the 1994 election his proof of concept. Thus even though Democrats won their seat, they lost the long-term narrative.

When pundits look back at the 2000 presidential election, the lesson they tend to draw is that what really matters in a recount is raw power. Who cares that the Supreme Court’s Bush v. Gore decision was, by many lights, among the most partisan, least legitimate rulings ever issued? George W. Bush, not Al Gore, became president.

But what’s at stake in this year’s recount is not the presidency—it’s a Senate seat that won’t determine which party controls that chamber, and a governorship that was previously in Republican hands. Of course the result matters, but, as in the fight over the Bloody Eighth, the narrative matters, too. Indeed, how the public perceives the process could influence the 2020 election (and beyond) more than the actual outcome. Which side will claim the mantle of justice? Which will end up looking corrupt?

What Do You Know … About Education?1. In what was effectively the first-ever State of the Union address delivered at the then-provisional U.S. capital of New York City, this president pushed forward the idea of a national university in America.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. This public-schools superintendent and Democratic gubernatorial candidate defeated the two-term Wisconsin governor Scott Walker in last week’s midterm elections, running with a focus on education policy.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. According to a recent national survey, 58 percent of white people with a college degree say that America has gotten better since 1950. But this percentage of white people without a college degree say it’s gotten worse.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: George Washington / Tony Evers / 57

Dear TherapistEvery week, the psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb answers readers’ questions in the Dear Therapist column. This week, Evan from Delaware writes in about stressful living in a multigenerational household:

I am 24 years old and have lived at home with my grandparents and mother since I was in college. It was a nice arrangement for many of those years, and the deal has been simple: I get to live at home for basically nothing, and in return I clean, run errands, occasionally cook, and take care of whatever they need. In addition to this, for the past eight months I have been working part-time, and I’m actively seeking full-time work.

However, about seven months ago the arrangement changed rather dramatically. My grandfather had been suffering mildly from Parkinson’s disease and had not had many issues, but one day he fell and ended up in the hospital. This was followed by a short stay at a recovery home, and finally he came back home …

My grandfather has gotten better since then, but much of the same routine continues, with me being at my grandparents’ and mother’s beck and call for everything from the essential to the mundane. Every day I become more and more annoyed by their endless requests and nitpicking. I feel like home is just another job, and it’s hard to open up or connect to someone my own age about it, because no one I know is in the same situation.

Read Lori’s advice, and write to her at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Atlantic Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Written by Madeleine Carlisle (@maddiecarlisle2) and Elaine Godfrey (@elainejgodfrey)

Today in 5 LinesMultiple wildfires have engulfed California. The Camp Fire in Northern California is now the deadliest wildfire in modern California history, with 29 confirmed dead. The Woolsey Fire raging in the southern part of the state has forced 265,000 people to evacuate in Ventura and Los Angeles counties.

Mississippi Democratic Senate candidate Mike Espy criticized his opponent Republican Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith after a video emerged of her joking about attending a “public hanging.” Espy and Hyde-Smith will enter a runoff on November 27, and if Epsy wins he will be the state’s first black Senator since Reconstruction. Hyde-Smith has not apologized for her comments.

A Florida judged ruled against Senate candidate Rick Scott’s lawsuit alleging voter fraud in Broward County. In Georgia, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacy Abrams filed a lawsuit on Sunday to block two counties from rejecting absentee ballots with minor mistakes, potentially pushing the election into a run-off.

Arizona’s Senate race has not been called, but Democratic candidate Kyrsten Sinema’s lead over Republican Martha McSally has widened.

Police officers responding to a shooting early Sunday morning in Midlothian, Illinois shot and killed the 26-year-old black security guard, Jemel Roberson, who was on duty at the bar. The Cook County Sheriff’s office has launched an investigation into Roberson’s death.

Today on The AtlanticCalifornia, Ablaze: Three of California’s five largest fires on record have occurred in the last three years. The worst is likely yet to come. (Robinson Meyer)

‘Institutionalized Terror’: What happens when a nation ends birthright citizenship? Jonathan M. Katz looks at a case study of one country that did: The Dominican Republic.

Trump 2020: Despite the the Republican Party’s recent losses in the House, here’s why President Trump has a good shot at being reelected. (David A. Graham)

Shame on Amazon: The company's 14-month performative bidding war for its second headquarters is not only disgraceful, but should be illegal, writes Derek Thompson.

Remembering Matthew: As America struggles to confront bigotry, Matthew Shepard's legacy remains pertinent, writes Megan Garber.

Snapshot Firefighters battle the Woolsey Fire as it continues to burn in Malibu, California, U.S., on November 11, 2018. (Eric Thayer / Reuters)What We’re Reading

Firefighters battle the Woolsey Fire as it continues to burn in Malibu, California, U.S., on November 11, 2018. (Eric Thayer / Reuters)What We’re ReadingA Lesson in Kansas: Democrat Laura Kelly beat Trump-aligned candidate Kris Kobach in the Kansas gubernatorial race last Tuesday. How Kobachlost could be a playbook for how Democrats can defeat Trumpism. (Jane Mayer, The New Yorker)

The Forgotten Culture War: American conservatives were once staunch opponents of pornography. Now it’s a rapidly growing industry—with few adversaries. (Tim Alberta, Politico)

The Rise of E-Carceration: Michelle Alexander writes that the current trends of criminal justice reform toward dependence on algorithms and electronic monitoring risk building a new system “more dangerous and more difficult to challenge than the one we hope to leave behind.” (The New York Times)

A Star Is Born: Who Is Dan Crenshaw? The Republican Congressman-elect who appeared on SNL over the weekend is a rising star in the Republican Party. (Dan Zak, The Washington Post)

What a Wall Can’t Stop: As the Trump administration pushes for more border wall, the amount of smuggling tunnels running under the U.S.-Mexico border has only increased. (Sarah Troy, High Country News)

VisualizedThink Locally: Republicans still control large swaths of state politics. But Democrats made headway in the midterms. (Emily Badger, Quoctrung Bui, and Adams Pearce, The New York Times)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Matthew Palmer’s mother, Susan, doesn’t believe in clairvoyance. She can’t reconcile that, however, with the fact that a psychic predicted—with inexplicable accuracy—her husband’s untimely death. It would happen, said the fortune teller, when her son turned 13. At that point, Susan didn’t even have a son.

After Palmer was born, his parents would sometimes joke about the psychic’s prediction. Then, three weeks following Palmer’s 13th birthday, his father died. Susan recounts the eerie story in What the Psychic Saw, Palmer’s short documentary, told entirely through archival home videos and a recorded phone call with his mother.

“I only learned of the impact the psychic’s words had on my mom while making this film,” Palmer told The Atlantic. According to the filmmaker, the shock and trauma of his father’s sudden death left Susan with limited emotional capacity. She couldn’t process the fact that the prediction had come true.

“It wasn’t until about a year later, when life became more stable and manageable emotionally, that I reflected on the prediction,” Susan said. “At that point, my reaction was one of awe and discomfort.”

Like his mother, Palmer doesn’t believe that psychics can predict the future. “But the fact that this one did just that still amazes [my mother],” Palmer said. “A few times when she’s told the story, she ends it with some variation of ‘Who knows?’ as if to say that maybe—just maybe—some people know things about the universe that we don’t.”

Stan Lee was just 16 when he got his first job in the comic-book industry; in 1939 he joined Timely Comics, a new pulp division belonging to the publisher Martin Goodman. Born Stanley Lieber, the son of Romanian Jewish immigrants dreamed of writing the “Great American Novel.” He later said he took the nom de plume Stan Lee out of embarrassment: “People had no respect for comic books at all. Most parents didn’t want their children to read [them].” After a nearly 80-year career in comics, Lee died Monday at the age of 95 as the ultimate icon of the industry, the creator of characters like the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and the X-Men. His name is essentially synonymous with the American superhero comic, which has become an art form unto itself.

Lee’s initial work saw him keeping the inkwells filled and getting lunch orders. He quickly graduated to proofreading and editing, making his writing debut on a small story in 1941’s Captain America Comics Issue No. 3. Lee worked with legends like Joe Simon, Jack Kirby, Bill Everett, and Syd Shores before entering the U.S. Army in 1942. Upon his return, Timely Comics had been renamed Atlas, and superheroes had fallen out of vogue. Lee dutifully worked within the popular genres of the ’50s—romance, Westerns, and sci-fi—but he came close to quitting the industry out of boredom.

But by the late 1950s, the Atlas rival DC Comics had successfully revived some of its heroes past, including the Flash and the Justice League of America. Intrigued, Goodman assigned Lee and Kirby the task of creating their own superhero book, though Lee (who was given to mythmaking) said that his wife played a part in nudging him toward writing a comic he actually wanted to read. Together, Lee and Kirby produced The Fantastic Four, about a team blessed with unique powers, in 1961.

It was a commercial sensation, one that stood out from most comic books because of its tremendous sense of pathos. Superheroes, until then, had been framed as one-dimensional forces of justice, pillars of honor and duty serving a higher cause. The Fantastic Four were prone to bickering, wrestled with romantic drama of their own, and were recognizably flawed people, each with the potential to be remote, hotheaded, or arrogant. Lee and Kirby collaborated on Fantastic Four for 102 issues; the “Galactus trilogy,” spanning issues 48 to 50, is the indisputable pinnacle of the so-called Silver Age of comic books.

[Read: Stan Lee’s definition of the American idea, in comic form]

Lee and Kirby created many vital characters together, including the X-Men, the Hulk, the Avengers, Nick Fury, the Silver Surfer, and Thor; Lee also created Spider-Man and Doctor Strange with the recently departed Steve Ditko, Iron Man with Don Heck and Kirby, Daredevil with Everett, and many more. Lee relied on a writing approach he dubbed “the Marvel method,” where he would create a short story synopsis, the artists would draw the story themselves and create the plot-by-plot details, and then Lee would fill in the dialogue (he was fond of hyperbolic narration, goofy one-liners, and topical references).

That method led to many disputes over the years with Lee’s top collaborators. Certainly visionaries like Kirby and Ditko deserved just as much credit for the characters they created, though Lee was often reticent to grant it. The extent of Lee’s contributions to any particular Marvel Comics issue can be argued over endlessly, but the writer played a huge role in making comic-book storytelling what it is today. He emphasized character as much as action; was fond of serialized, soapy twists; and tried to keep his heroes relevant to the age they lived in, rooting stories in the countercultural movements of the day.

In 1972, Lee stopped writing comics and became Marvel’s publisher. He gradually transitioned into a figurehead role for the company, serving as a mascot of sorts and only occasionally writing issues. Still, his imprimatur remained crucial to Marvel as it continued to evolve with the times. By 2008, when the company made the risky play of launching its own film series with Iron Man, Lee was there to film a cameo role and give a sly wink and nod to the audience.

“I used to be embarrassed because I was just a comic-book writer while other people were building bridges or going on to medical careers,” Lee, who eventually took his pseudonym as his legal name, once said. “And then I began to realize: Entertainment is one of the most important things in people’s lives. Without it, they might go off the deep end. I feel that if you’re able to entertain, you’re doing a good thing. When you’re seeing how happy the fans are—as they [see up-close] the people who tell the stories, who illustrated them, the TV personalities—I realize: It’s a great thing to entertain people.”

Throughout his decades in the industry, that was Lee’s primary impulse: to entertain. Few can claim such a long legacy of sheer joy in their art, and whatever initial embarrassment he felt filling up those inkwells at Timely Comics, it vanished long ago. ’Nuff said.

As Florida begins a statewide recount to determine the outcome of its gubernatorial and U.S. Senate contests, commentators are rehashing the famous Bush v. Gore recount of 2000. That’s the most obvious reference—the same state and even some of the same counties are at issue, after all—but it’s not the only or even the most useful one. Democrats in particular should look to the now-forgotten fight over Indiana’s “Bloody Eighth” Congressional District.

Immediately after President Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory against Walter Mondale in 1984, which also returned to Congress a Democratic majority in the House and a Republican majority in the Senate, a bruising battle unfolded over Indiana’s Eighth Congressional District. The freshman Democrat Frank McCloskey, a 45-year-old first-term Democrat, led the Republican Richard McIntyre, a promising 38-year-old conservative state legislator, by 72 votes after the initial count. But a tabulation error in one county seemed to swing the election to McIntyre, by just 34 votes, at which point the Republican secretary of state, Edward Simcox, certified McIntyre the victor. After a full recount, McIntyre was up by some 400 votes—but many thousands of ballots were not counted for technical reasons.

The tight race was not a total surprise, since, like Florida today, the Bloody Eighth of Indiana, as it was known, was a notoriously competitive swing district.

[Read: Brian Kemp’s lead in Georgia needs an asterisk.]

Democrats responded with intransigence. They said that Simcox had certified the election prematurely, and that “irregularities” put the apparent result in doubt, including allegations that Republicans had unfairly disqualified a sizable number of African American voters in the urban parts of the district. When McIntyre arrived on Capitol Hill on January 3, 1985, Democrats refused to seat him; the House voted 238 to 177, along strict party lines, to keep the seat vacant pending a congressional investigation and a new recount.

Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, the Majority Leader Jim Wright, and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee chairman Tony Coelho charged one of their own, Representative Leon Panetta, to lead the recount. Under Panetta were two Democrats and just one Republican. Republicans cried foul that the majority was trying to steal the election. Even Minnesota’s Bill Frenzel, a gregarious Republican who was known as a moderate in his disposition and politics, characterized the process as a “rape” of the voters.

Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich, a young renegade elected in 1978, saw an opening to score partisan points. Gingrich was the leader of the Conservative Opportunity Society, a caucus of right-wing Republicans that he created in 1983. One of its goals was to encourage a more aggressive approach to challenging Democrats, who had been in the majority since 1954, than the 62-year old House Minority Leader Robert Michel had been willing to try. COS wanted to break with conventional norms and stretch procedure as far as possible to advance Republican objectives.

The Indiana recount fit nicely into Gingrich’s plans. Gingrich worked to convince reporters that this was a scandal of Watergate-like proportions. Indeed, he told one of his acolytes, Joe Barton of Texas, that the public needed to understand that “this is a constitutional issue! We have to make the press understand that.”

[Read: Stacey Abrams is still waiting for a miracle.]

Guy Vander Jagt, the chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee, was initially reluctant to take Gingrich’s advice. He feared that doing so would blow up any chance of future bipartisan civility. But he quickly caved. Vander Jagt sent out to every Republican in Congress a draft of an op-ed titled “Stealing a Seat.”

Partisan tensions reached a boiling point when Panetta’s task force determined in late April that the seat should go to McCloskey. By a party-line vote of two to one, the committee decided that McCloskey had won by four votes, 116,645 to 116,641. Republicans went ballistic. “I think we ought to go to war,” the Wyoming Republican Dick Cheney declared.

Seeking retribution, Republicans kept their colleagues in session all night after the committee announced the recount outcome and prevented the House from conducting any business for three days. Live on C-SPAN, a relatively new channel created in 1978, Republicans delivered one tirade after another alleging that Democrats were stealing an election.

Nevertheless, on May 1, the House voted 236 to 190 to seat McCloskey, with 10 Democrats joining the unanimous Republican opposition. And by a vote of 229 to 200, the House once again rejected a Republican proposal to hold a new special election to settle the matter at the ballot box.

Republicans weren’t quite finished, though: Theatrically, they stormed out of the chamber before O’Neill could officially seat McCloskey. “Would the gentlemen remain within until I have had an opportunity to administer the oath?” O’Neill asked. “No!” yelled House Minority Leader Robert Michel, usually considered one of the most civil voices on Capitol Hill.

As O’Neill swore McCloskey into office, Republicans stood side by side on the steps leading out of the House chamber to speak with reporters. “This has united the Republican Party as nothing else,” McIntyre told the press. “The American people are not going to forget.” Republicans compared Democrats to “slime” and “thugs.”

Some Democrats were uncomfortable with the outcome, which they considered dubious. The Massachusetts Democrat Barney Frank, for example, voted against the committee recommendation. O’Neill, Frank recalled, was “mad at me until I explained myself; then he became furious.”

[Read: The Democrats’ Deep South strategy was a winner after all.]

But most Democrats brushed aside the criticism. In their minds, what mattered most was that they’d held the seat. They didn’t understand that Republicans had succeeded in convincing the public that something was amiss—that, perhaps, the very legitimacy of the Democratic majority was suspect. Nor did they anticipate how the Bloody Eighth would embolden Republicans, convincing many of them that Gingrich’s way of thinking was fundamentally correct. In short: Enough with bipartisanship; it was time for a do-anything approach to taking back control of the House. “It validated Newt’s thesis,” Vin Weber, a COS ally, recalled. “The Democrats are corrupt, they are making us look like fools, and we are idiots to cooperate with them.”

Arguably, the Bloody Eighth is what led to the eventual GOP takeover of the House, under Gingrich, in 1994. The Bloody Eighth was his trial run, and the 1994 election his proof of concept. Thus even though Democrats won their seat, they lost the long-term narrative.

When pundits look back at the 2000 presidential election, the lesson they tend to draw is that what really matters in a recount is raw power. Who cares that the Supreme Court’s Bush v. Gore decision was, by many lights, among the most partisan, least legitimate rulings ever issued? George W. Bush, not Al Gore, became president.

But what’s at stake in this year’s recount is not the presidency—it’s a Senate seat that won’t determine which party controls that chamber, and a governorship that was previously in Republican hands. Of course the result matters, but, as in the fight over the Bloody Eighth, the narrative matters, too. Indeed, how the public perceives the process could influence the 2020 election (and beyond) more than the actual outcome. Which side will claim the mantle of justice? Which will end up looking corrupt?

Republicans understand that. President Donald Trump has been tweeting allegations that Democrats are up to no good. “Trying to STEAL two big elections in Florida!” he tweeted. “We are watching closely!” Senator Lindsey Graham joined in to say, “They are trying to steal this election. It’s not going to work.” Rick Scott has filed several lawsuits against county officials. He claims that there is evidence of fraud, even though state officials have found none.

Democrats need to counter GOP talking points with a clear message that they are trying to protect the integrity of the U.S. election system. The fight for a fair recount, they must explain, is a fight to push back against several decades of conservative attempts to restrict the franchise and undermine the legacy of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Every eligible person should be able to vote, and their votes must be counted. Those are bedrock principles for any democracy. Andrew Gillum, the Democratic candidate for governor, already took a step in the right direction by exchanging his election-night concession for a defiant statement: “I am replacing my words of concession with an uncompromised and unapologetic call that we count every single vote.”

Recounts are much more than legal disputes; they are fundamentally political fights. And in politics, story matters.

In October 1998, Reggie Fluty, a police officer responding to a phoned-in tip, came across a limp figure strung up on a fence in a desolate field on the outskirts of Laramie, Wyoming. There had been, initially, confusion about what Fluty was responding to: The teen boy who had called in the tip had initially assumed, riding his bike across the field, that he’d seen a scarecrow. He had not. The figure was the body of Matthew Shepard, 21 years old and a freshman at the University of Wyoming, who had been tied to the fence by two men he’d met in a bar in Laramie. They had robbed Shepard of the money in his wallet—$20—and then struck him across the head, repeatedly, with the butt of a large Smith & Wesson revolver. (The blows were so severe, a sheriff would later conclude, that Shepard’s injuries, including a fractured skull and a crushed brain stem, were less consistent with a beating than with a high-speed traffic collision.) The men then left Shepard, bloodied and swollen and barely alive, in the biting cold of the prairie night. It would be 18 hours before the bike-riding boy would find him.

The New York Times would later see in Shepard’s body, strung to that fence in the shadow of the snow-dusted Rockies, echoes of the Western custom of nailing dead coyotes to boundary markers—a warning to those who might consider intruding on private property. A message meant to foment fear, and also to make a statement about who belongs in a given space and who, in the assessment of the owners of the barriers, does not.

The state of Wyoming did not, in October 1998, have legislation against hate crimes. Despite everything that has taken place there, and in the country at large, since, it is one of five states that still lack such laws. The men who met and robbed and beat Shepard—who left him to die of his injuries nearly a week later in a hospital room in Colorado—were instead convicted of kidnapping and murder. They are each currently serving multiple life sentences for a killing that was a hate crime in practice if not in legal classification: The men beat Matthew Shepard, who was gay, because he was gay.

Because of that, Shepard, in his death, became an instant symbol: of bigotry, of violence, of hatred that is at once senseless and tragically consequential. His murder made national news those 20 years ago, horrifying a nation that reliably assumes itself to be better than it is. Lingering outrage about the murder inspired Congress to pass legislation against hate crimes: the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act—Byrd, a black man, had been chained to a truck and dragged to his death by white supremacists in July 1998—signed by President Barack Obama in 2009. Her son had always wanted his life to be meaningful, Shepard’s mother, Judy, would later comment; his horrific death brought a tragic fulfillment to that desire.

Twenty years later, Matthew Shepard remains a symbol of the tragic consequences of bigotry. His family, however, is hoping that he’ll live on in the American historical memory as much more than a martyr. To mark the anniversary of his death, Shepard’s family recently donated a collection of his belongings to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, which houses an extensive collection of LGBTQ-focused objects and documents. The items are currently not being exhibited in the museum’s public halls but are available to researchers; I was given an introduction to them by Katherine Ott, the museum’s curator for medicine and science, and Franklin Robinson Jr., the archivist at the Smithsonian who manages Shepard’s papers.

The items are familiar, even in their specificity. (“He grew up,” Ott put it, “as a typical young queer kid, finding his way.”) There’s the Superman cape, shiny and red and handmade by Judy Shepard, that Matthew Shepard had once worn as a costume. There’s the pair of his sandals, their soles still covered in a thin layer of mud. There’s the 4-H ribbon from the Wyoming State Fair that Shepard had won, Ott told me, for a cornbread recipe he and his mother had developed together. There’s a fourth-place ribbon for a track event. (Of Shepard’s lack of athletic prowess, Ott put it like this: “His parents said, ‘Fourth place—that means there were four people in the race.’”) There’s the small, plush pair of lips with kiss stitched onto them that Judy Shepard would include in her son’s lunch bag every day.

The Superman cape Shepard wore as a child (Richard W. Strauss / Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History)

The Superman cape Shepard wore as a child (Richard W. Strauss / Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History)There’s the thick, gold ring Shepard had bought with the intention that one day he would give it as a gift to his future husband. He’d had it customized. “He was a romantic,” Ott said.

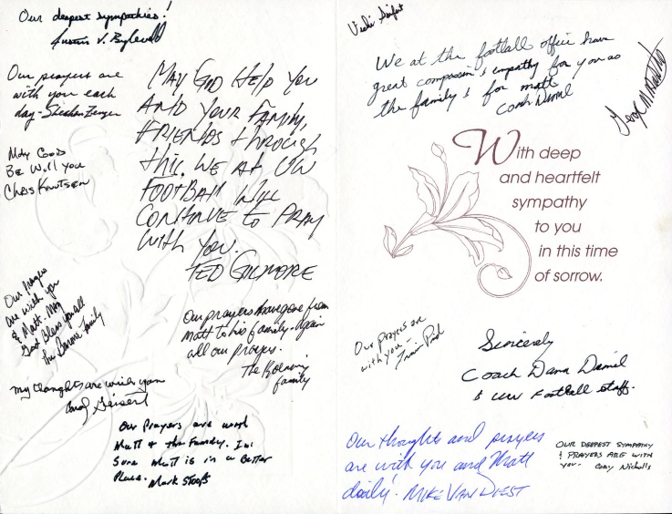

There’s also the collection of documents, housed away from the objects in a specialized archives area: stacks of condolence letters sent from Americans across the country to the Shepards, as the news of their son’s death reverberated across the country. A store-bought sympathy card scrawled with brief notes by members of the University of Wyoming’s football team. The brightly colored paper art—construction and tissue—that Shepard had made as a boy. The pencil-scrawled note from one of Shepard’s grade-school teachers, encouraging him to stay strong in the face of bullying about his small size: “Did you know,” it reads, “the very best things are often in small packages? I think you’re WONDERFUL. Love, Mrs. Babb.”

A sympathy card, signed by members of the University of Wyoming’s football staff, given to Shepard’s family after his death (Joe Hursey / Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History)

A sympathy card, signed by members of the University of Wyoming’s football staff, given to Shepard’s family after his death (Joe Hursey / Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History)Something can happen, when a tragic twist turns an ordinary life into an extraordinary one, to the person at the other end of the transformation: The idea of the person can overcome the truth of the person. A life, with all its kindnesses and contradictions and small truths and big ones, can give way to the soaring slights of hagiography. The symbolism—the martyrdom—can overtake everything else. That happened in 1998, as Matthew Shepard the person became Matthew Shepard the icon. His death would go on, in short order, to inspire multiple plays, and a film, and a chorale piece. His murder would become the subject of documentaries. It would become the subject of controversies. Elton John would write a song, “American Triangle,” about the circumstances of the slaughter. The fence where Shepard was left for dead, on that rocky prairie strewn with sagebrush and range grass, was briefly turned into a shrine, a repository for flowers and gifts and notes from people who did not know Matthew Shepard but, in another way, did. The fence would eventually be disassembled and removed, as if the landscape itself were ashamed of what had been allowed to take place on its barren expanse.

The objects in the Matthew Shepard collection, moved from the garage of the Shepard home in Casper, Wyoming, to the protective environs of the nation’s foremost historical museum, resist such acts of erasure. They are insistently present, and meaningfully—painfully—ordinary. They emphasize who Matthew Shepard the person was before he came Matthew Shepard the icon. He loved politics, and hoped one day to become a diplomat with the State Department. A child of Wyoming, he liked to camp and hunt and fish. He loved to act. He was exceptionally kind. He was unusually sensitive. In grade school, he’d dressed as Dolly Parton for three Halloweens in a row. In high school—his father was an oil-safety engineer for Aramco, the Saudi Arabian oil company, and his parents were stationed in the Gulf—Shepard attended an American school in Switzerland. While he was abroad, during a trip to Morocco, he’d been attacked and raped. He had just been emerging from the depression that the trauma had triggered, just been rebuilding himself and his life, when he was killed.

Shepard had been struggling. He’d been trying. He’d been hoping that things would get better. His papers, now filed and stored in a temperature-controlled facility that protects history for the future, testify to all that. Seen through the prism of the documents, Robinson, the archivist, put it to me, no longer is Shepard merely an image or an icon or “a symbol for the LGBT community and for hate crimes.” Instead, the objects encourage their viewers to ask, Robinson said, “If he had lived, what could he have accomplished?”

They ask other questions, as well, about the profound contingency of historical memory—the way some people are converted into icons, remembered and celebrated; the way others recede from view. The Shepard collection, evocative in its ordinariness, serves as a reminder that for every Matthew Shepard, enshrined in a museum—and for every James Byrd Jr., and for every Emmett Till, and for every other person whose name has been inscribed, in bold type, into the texts of American history—there are so many more. People who were robbed of their life by those who were fueled by hatred. People who are anonymous in their victimhood and silent in their suffering—people whose life has been made harder and sadder and worse than it might have been because there is a significant portion of people who look out on the American landscape and, gazing at all the rugged beauty, focus on the fences.

On October 26, in an event planned to coincide with the 20th anniversary of his murder, Matthew Shepard was interred at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. His family, in the past, had been reluctant to make such a move, fearing that his resting place might be vandalized by bigots; finally, however, they agreed to it, and Shepard’s cremated remains were placed in the soaring structure’s crypt, near those of Helen Keller and Woodrow Wilson. As part of the interment ceremony, a service celebrating Shepard’s life was held in the cathedral. It featured readings that sought light in times of darkness, and songs that emphasized love as a weapon against hatred. It was profoundly hopeful.

The day after the ceremony, a man driven by anti-Semitism burst into another such service, this one being conducted at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. With three pistols and an AR-15, he slaughtered 11 worshippers and injured seven more. It was the deadliest act of violence against the Jewish community in the nation’s history. It was also one more reminder of how normal hatred remains in a country that prides itself, despite so much evidence to the contrary, on its enlightenment. One more piece of evidence that violence, in America, is another thing that remains ordinary.

Smino isn’t afraid to get a little weird. The North St. Louis–bred rapper twists his voice into dizzyingly distinct harmonies. He delights in the indulgent poetics of slant rhyme. He weaves multiregional R&B into the tapestry of his rap.

The 27-year-old’s newly released sophomore album, NØIR, builds on his years of making funky, soulful music. It’s soothing, inventive, and fun. The video for “L.M.F.,” the album’s first single, begins with a phone conversation between two women. One of them relays the sight of Smino “riding around with a whole monkey on his lap,” then quickly gets to the reason for her call: “That nigga done went and got real Hollywood or whatever, but I did hear he was having a kickback tonight though.”

And so begins the charming conceit of the video: a giant dinner-turned-party, hosted at the rapper’s family home. Smino and his “monkey” (really a lemur) entertain guests with the help of a crew of aunties—and a version of Smino meant to look like his father, complete with gray hair, thick-rimmed glasses, and business-casual attire. The video’s bright yellows, reds, and greens leap off the screen. The scent of doughy dinner rolls and freshly snapped green beans and weed smoke practically wafts through the frame. It’s a delightful vignette, but the appeal of “L.M.F.” extends beyond this bite-size Soul Food. The song’s chorus is impossibly catchy—and captures Smino’s range of influences with remarkable precision:

Said she Rafiki, you a lion, Mufasa

Baby ain’t nothing ’bout me PG, rated X for extraordinary

The Mary got me merry, now I’m singing like Mary Mary

The coupe going stupid, call it Cupid it’s February

That Smino would reference both marijuana and the celebrated gospel duo Mary Mary in the same bar is just one example of the saucy, winking lyricism that characterizes his music. He excels in these moments, capturing the small rebellions of black youth without overstating any incongruence. The line also functions as a nod to his musical roots. Born Christopher Smith Jr., the young Smino began listening to rap largely at a cousin’s house because he wasn’t allowed to do it at home, where his parents insisted on “a bunch of jazz music, a bunch of soul music, so much gospel music,” as he recently told Rolling Stone.

On “Anita,” the second single from his debut album, BLKSWN, the artist offered a groovy dedication to the legendary singer-songwriter Anita Baker (and to all black women). Frequently name-checking his musical forerunners, Smino is both deferential and imaginative. On the track, which the musical juggernaut T-Pain later remixed, Smino’s affections send his voice into ecstatic wails somewhere between R&B and gospel. “Turn up the vala-yume,” he sings, stretching the word into three smooth syllables. “This feel like hallelu-jah.”

Eighteen months later, NØIR brings black love full circle. The album opens with “KOVERT,” which begins with a seductive whisper from Smino’s longtime girlfriend and frequent collaborator, the musician and filmmaker Jean Deaux. “Noir, what a beautiful name. Black, statuesque, you know?” she breathes. “Strong, sweet, that’s what I think when I think of Noir. That’s what I think when I think about you.” It’s a fitting start to an album that spends much of its 58-minute run time exploring the burdens and beauty of black life.

After “KOVERT,” Smino’s vocal zigzags and lyrical twists set the course for the album. The bounces of the Sango-produced “L.M.F.” are immediately followed by “KLINK,” the album’s second single. The song is named for the sound Smino’s many chains make as they clang against one another, and silvery production from the Chicago producer Monte Booker matches this metallic quality. The Windy City has become a second creative home for Smino, and several Chicago artists lend their talents to NØIR. On the booming “KRUSHED ICE,” the G.O.O.D. music signee Valee amps up the St. Louis rapper’s braggadocio. Smino reunites with the singer Ravyn Lenae for “MF GROOVE,” an aptly titled track that contrasts their ethereal voices with funky electronic production from the rapper himself. Like their prior collaboration, BLKSWN’s gorgeous “Glass Flows,” the song is absorbing and confident.

On “Z4L,” a bouncy and infectious track featuring the Chicago rappers Bari and Jay2, Smino employs a cartoonish trick of the tongue. “Neck on vegan, freezing, check my color palette, white like a bunny wabbit,” he raps before adopting a Looney Tunes–ian tone that recalls the antics of Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny. “You know I keep some carrots, eat a bitch like a sandwich.” The slip into vocal caricature is self-aware and comedic without tipping into blunt parody. Elsewhere, Smino stretches and contorts and relaxes his voice into more colloquial patterns. “PIZANO” finds him rhyming at a frantic pace on its verses, then vibing out on soulful choruses, describing a blunt so big, “it look like Green Goblin.”

The brand (this time its lingerie subsidiary) gets referenced again on the next track, “MERLOT”: “My boo don’t like designer shit / All she want is that Rihanna shit.” Later, Smino names an entire song “FENTY SEX.” The Dreezy-assisted song isn’t a salacious send-up of the famous Bajan singer and beauty mogul (as many men have done). Instead, it’s a sultry ode to an unnamed woman, a hypnotic offering laced with references to tropical fruit and flowery marijuana. It builds on the musical world of the final single from BLKSWN, “Wild Irish Roses,” a languid chronicle of drinking fortified wine and searching for Backwoods tobacco leaves with a lover.

Smino’s unabashed catering to the Fenty Beauty–wearing, natural-hair-having, coconut-oil-drenched demographic is a hallmark of all his creative endeavors. Zero Fatigue, the label he shares with Booker, Lenae, Bari, and Jay2, sells hoodies lined with satin—perfect for those whose textured hair requires protection from the breakage that harsh fabrics like cotton can cause. His visuals are similarly plaited. The NØIR cover depicts Smino sitting on the floor while a woman braids his hair. It’s all very D’Angelo, very Mario, very Maxwell. And it works—because the music does, too. Smino sounds the way Backwoods smell: warm, earthy, full-bodied. NØIR creates its own hazy world.

Where another artist’s catering to black listeners—and black women in particular—might come off as a cynical marketing ploy, Smino’s love of his people has always seemed homegrown. Some of that can be heard in the drawl of his voice, but it’s also in the substance of his words. The artist has long been concerned with the well-being and artistic pursuits of black people. Smino’s hometown pride swelled in the months and years following the police killing of Michael Brown in neighboring Ferguson, a devastating injustice that galvanized the local community and then black people around the country. “Black people only make up 13 percent of the U.S., but I’d rather satisfy that than any other percentile,” he told The Fader in 2017. “If something happens to me, I know who goin’ rally behind me. I’ve seen it.”

Smino’s music avoids sensationalizing the spectacle of hardship, but he doesn’t shy away from naming what haunts him. “It was gruesome / what we grew from,” he sings on NØIR’s “SPINZ,” before repurposing the words. “But we grew some in the end.” It’s a deft rhyme, a poetic reinterpretation. On NØIR, Smino keeps singing us love songs.

John Cuneo

John CuneoOne afternoon in the summer of 2013, Anna Todd was in the checkout line at Target when, as most of us do, she pulled out her phone. Then she propped her elbows on her shopping cart and began to type.

Todd was 24 years old and living near Fort Hood, Texas, with her husband, a soldier she had married a month after graduating high school, and their newborn, who suffered daily seizures. While caring for her son and taking online community-college courses, she helped support the family by babysitting for a neighbor and working the beauty counter at Ulta. For fun, she read. Wuthering Heights, Twilight, The Things They Carried. Since the previous fall, she’d also indulged an addiction to One Direction fan fiction—stories featuring the boy band in imagined scenarios. After blazing through all that she could find online and then tiring of waiting for updates from erratic authors (many of them teens juggling writing and school), Todd decided to attempt her own series. She called it After and wrote on her smartphone whenever she could steal a moment—while shopping for groceries, waiting to get her teeth cleaned, riding in friends’ cars. She used a pseudonym (imaginator1D) and hid her alter ego from family and friends. “My husband just thought I had a phone addiction or something,” she has said.

Without pausing to proofread, Todd uploaded a chapter a day to Wattpad, a free site that has earned a reputation as the YouTube of ebooks for its success in giving prose the social-media treatment. (Readers can chat with writers and discuss books with one another by leaving comments alongside the text as they read.) After, generously sprinkled with Pride and Prejudice allusions and oral sex, opens on Tessa Young, an innocent bookworm beginning her first day of college. It follows her torrid, tortured romance with the brooding sophomore Harry Styles—named after the One Direction heartthrob—as he initiates her into heavy drinking, heavy makeup, and heavy petting. (Aside from his accent, After’s Harry bears little resemblance to the British singer.)

By the time Todd wrote Chapter 90—of an eventual 295 chapters—her novel-in-progress had been read more than 1 million times. Multiple literary agents reached out to her, but she dismissed them as “crazy people,” figuring no legitimate professional would seek out One Direction fan fiction. Readers composed sequels starring After’s characters, uploaded video homages to the book, and—finally convincing Todd that she might have something big on her hands—chatted as Tessa and Harry on Twitter role-playing accounts. Seeing that, “I was like, ‘Holy shit,’ ” Todd once recalled. Representatives from Wattpad, which had never had such a blockbuster, contacted Todd and offered to help connect her with publishers. Before she flew to meet with Wattpad’s staff at the start-up’s Toronto headquarters, she overdrafted her bank account to pay for her passport.

Since then, Todd’s After series has been published as four volumes by Simon & Schuster in a six-figure deal, earned a spot on the New York Times best-seller list, been read nearly 1.6 billion times on Wattpad, been translated into more than 35 languages, and been adapted into a feature film, which Todd is co-producing, and which co-stars Selma Blair. (For the print and movie versions of After, Harry Styles has been renamed Hardin Scott.) On a recent book tour through Europe, cheering fans swarmed train stations waiting for Todd to disembark.

Her franchise has also helped establish Wattpad as a hub for young people drawn to its interactive approach to the written word. The site’s 65 million monthly users, who are overwhelmingly female and under 35, spend an average of 30 minutes a day reading authors who range from middle schoolers to Margaret Atwood. Building on its collaboration with Todd, Wattpad has helped hundreds of stories be adapted into books, TV shows, or films through deals with HarperCollins, NBCUniversal, Sony Pictures Television, and others; the site says it can forecast Gen Z hits and trends with far greater accuracy than industry gatekeepers acting on their gut. (Wattpad predicts that mermaids and cannibals are poised for stardom.) Netflix’s The Kissing Booth, described by an executive at the streaming company as “one of the most-watched movies in the country, and maybe in the world,” began as a Wattpad story written by a 15-year-old.

Todd sees no basis for the idea that young people have soured on books—a favorite complaint among those worried about kids these days. During my recent visit to her trailer on the film set of After, in Atlanta, she told me that an “insane” number of teachers had written to thank her for inspiring a love of reading. After discovering Tessa and Harry’s obsession with authors like Charles Dickens and F. Scott Fitzgerald, their students devoured classic literature. Todd recently lent her star power to several authors who in fan-fiction circles might be seen as underdogs: Her Italian publisher released special-edition translations of Anna Karenina, Pride and Prejudice, and Wuthering Heights prominently branded with Todd’s After-inspired logo (two interlocking hearts that form an infinity sign). “OMG PRIDE AND PREJUDICE IS LIKE AFTER,” tweeted one reader. “ANNA you are so smart I can’t even.”

Todd grew up in a trailer park in Dayton, Ohio. Her father, whom she describes as a drug addict, was stabbed to death shortly before her first birthday. She was raised by her mother, a caterer and longtime restaurant cook who also struggled with substance abuse, and her stepfather, who worked as a mechanic. Todd aspired to become a teacher or a nurse’s assistant, and remains mystified by her path to best-selling author and movie producer. “I never had any thought behind anything I did in the beginning, to be honest,” she told me.

Wattpad holds special appeal for Todd because it enables writers with backgrounds like hers—writers whose books would otherwise “never see the light of day because their names aren’t known, or they don’t have whatever following, or they don’t have experience in publishing”—to share stories that resonate with readers, regardless of whether those stories charm literary editors in New York. She worked with Simon & Schuster to publish her first book outside the After series, a retelling of Little Women called The Spring Girls. But she argues that publishing houses—“kind of an old machine”—are accelerating their decline by failing to consider a wide range of voices or offer young readers relatable protagonists. “The content that they’re pushing on young people is not what they want to read,” she told me in between takes, from her perch on a black director’s chair. “There’s so much anxiety coming from social media with teenagers that we have to give them characters that are real and that are not always happy; and that have bad parents and not great, supportive parents; and that are not going on these journeys to save the world with a bow.”

Todd understands more acutely than most writers what her readers want. She cultivates intimacy with her followers. (“You guys feel like my family,” she wrote in a Facebook post this September.) She participates in half a dozen Instagram group chats with her most die-hard fans—sneaking them behind-the-scenes footage of the After set—as well as a text-message chain with four readers she has befriended. (All of them, including Todd, got identical After-themed tattoos, and one adopted Todd’s English bulldog, Watty—named for Wattpad—when her hectic travel schedule made a pet unmanageable.) Rather than outlining her books—“it just messes up my entire story”—she prefers to “write socially.” With After, she’d review the comments on her most recent chapter and then tweak the story’s plot: If readers finished the section feeling happy, she’d throw in a twist to make them sad. If they were incensed at Harry, she’d have Tessa misbehave. “I had feedback every day, all day,” Todd said. “I always just felt like a puppet master playing with everybody’s emotions and doing this with the characters.” Wattpad is going even further by analyzing data on its stories—including sentence structure, vocabulary, readers’ comments, and popularity—in an effort to deduce exactly what makes a book succeed. In time, it may try to automate the editing process.