To the Left?: Democrats think they can pick up governor’s seats in these states this midterm election. Meanwhile in New England, popular Republican governors of solidly blue states seem to be holding on to their leads. In Texas, strategies like strict voter-ID laws and redistricting have kept the GOP in power, Adam Serwer argues, detailing his own laborious process of registering to vote there for the first time. But that grip may be loosening. In Iowa, a state that’s traditionally purple but has swung right in the past few years, Democrats may be well positioned to take back some seats. (Plus: Wherefore art thou, moderate candidates for office?)

Iran Dealt: A round of U.S. sanctions on Iran officially went into effect Monday. (This past May, the U.S. exited the Iran nuclear agreement, made under the Obama administration in 2015.) In the past, Iran has played with a number of obfuscations and legalities to skirt U.S. sanctions and continue selling its oil. Here are a few potential efforts, though—spoiler alert—many of these evasions will likely fail.

Enemy of the Good: Perfectionism in all its forms seems to be on the rise, psychologists are finding—from holding high standards for others to a desire to live up to social expectations to the self-directed kind. Do “we strive for perfection, it seems, because we feel we must in order to get ahead”? What are some ways to combat the negative impacts of aiming for perfection?

Snapshot What is the definition of “middle class” in America today? Is it best judged by household income, which can go further in Missoula, Montana, than in, say, Brooklyn, New York? “Today there can be no pretending that middle-class status is anchored by a single economic reality,” Caitlin Zaloom argues. “Instead, it is primarily an aspiration.” (Illustration by Katie Martin)Evening Read

What is the definition of “middle class” in America today? Is it best judged by household income, which can go further in Missoula, Montana, than in, say, Brooklyn, New York? “Today there can be no pretending that middle-class status is anchored by a single economic reality,” Caitlin Zaloom argues. “Instead, it is primarily an aspiration.” (Illustration by Katie Martin)Evening ReadDavid Frum debated Steve Bannon on stage in Toronto on the question of the future of Western politics—would it be populist, or would it be liberal?

Why share a platform, then, with Bannon, one of the most adept and successful of the challengers to all I hold dear?

I hoped to speak, first, to the small numbers of the genuinely undecided, to those who might imagine that populism offers them something. This is not true. The new populist politics is a scam and a lie that exploits anger and fear to gain power …

I hoped to speak, next, to the many people who see populism for what it is—and who resist it. Since the economic crisis of 2008 and 2009 and the Euro currency crisis that began in 2010, the so-called populists have won election after election in this country and in Europe. Even when the anti-populists have won, as they won in France in 2017, they have won by dwindling margins. Countries that formerly seemed secure against populism, like Germany, have been trending in ominous directions …

I hoped to speak, finally, to those who see populism for what it is—and support it. I hoped to look in the face of their most self-conscious and articulate champion, Steve Bannon, and tell them: You will lose.

The audience voted before and after the two sparred, to determine who moved the collective needle of the room. From beginning to end, it was a strange and heated affair.

What Do You Know … About Education?1. The Florida gubernatorial candidate Andrew Gillum, who’s played up his HBCU bona fides this campaign season, graduated from this 130-year-old university based in Tallahassee.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. The share of ___________________ degrees at elite research universities dropped from 17 percent a decade ago to just 11 percent today.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. One federal survey found that 70 percent of American teachers assign homework that needs to be done online. That’s a difficulty for the ______ percent of U.S. households with school-age children who lack high-speed internet at home.

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University / Humanities / 15

Dear TherapistEvery week, the psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb answers readers’ questions in the Dear Therapist column. This week, an anonymous reader writes in about a painful secret:

My parents divorced when I was very young, and afterward my father began sexually abusing me, which went on for years. I never told anyone in my family, and once I moved away from home I cut all contact with my father. I’m in my late 20s now, and my life is significantly better without him in it.

The problem is that my not talking to my father has started to raise questions. Recently my mother brought up the fact that I haven’t spoken to him in years and said something to the effect of “What could he possibly have done?” On the one hand, I’ve been through enough counseling to feel that I don’t owe anyone an explanation for not wanting a toxic person in my life, and bringing it up now, 10-plus years after the fact, wouldn’t change what happened. I’m also not emotionally prepared for the level of uproar it would cause if I started talking about it (my family are fabulous gossips).

On the other hand, I wonder if I should come forward. Many members of my mother’s family still have a friendly (if not especially close) relationship with my father, and I’d be lying if I said that didn’t hurt me a little.

Read Lori’s advice, and write to her at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Atlantic Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Written by Elaine Godfrey (@elainejgodfrey)

Today in 5 LinesThe U.S. renewed the sanctions against Iran that were lifted under the 2015 nuclear deal, but issued “temporary” waivers to eight countries, allowing those nations to continue buying oil from Iran without penalty.

NBC and Fox News said they will no longer air an immigration ad from President Donald Trump that has been widely criticized as racist. Facebook said it wouldn’t allow the video to run as an ad on its platform, but individual users can still share it.

The deployment of National Guard troops to the U.S.-Mexico border could cost at least $200 million, according to an estimate from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and figures from the Pentagon.

Trump is holding rallies in Ohio, Indiana, and Missouri to make his closing arguments ahead of Tuesday’s midterm elections.

Voters across the U.S. will head to the polls on Tuesday, the last of which will close at 11 p.m. ET. We’ll be back in your inbox tomorrow and Wednesday with special editions of the Politics & Policy Daily.

Today on The AtlanticFear and Loathing: Republican Representative Duncan Hunter of California is running the most anti-Muslim campaign in the country, writes McKay Coppins.

‘All Politics Is Local’: America’s current political culture focuses almost entirely on national-level issues and campaigns. Can these organizations shift voters’ attention to down-ballot races? (Emma Green)

How Far Have Democrats Moved Left?: There are more progressive candidates running than ever, but the most significant shift is among voters, not politicians. (David A. Graham)

A Twist in the Plot: David Frum agreed to debate against former White House strategist Steve Bannon about the false promise of populism. After the two faced off, things took a strange turn.

There’s Something Happening in Texas: Republicans in the Lone Star State have kept their majority by strategizing to disenfranchise black and Latino voters, argues Adam Serwer. But that won’t work forever.

‘The President’s Lies’: On the eve of the midterm elections, President Trump’s penchant for spreading falsehoods seems to be intensifying. (Vernon Loeb and Andrew Kragie)

Snapshot A boy looks to the stage as President Trump speaks during a rally at the IX Center in Cleveland, Ohio. (Carolyn Kaster / AP)

A boy looks to the stage as President Trump speaks during a rally at the IX Center in Cleveland, Ohio. (Carolyn Kaster / AP)Did Beto Blow It?: If Senator Ted Cruz’s Democratic challenger loses on Tuesday, it could be because he didn’t try to win over Republicans in a state as red as Texas. (Tim Alberta, Politico)

The Waiting Game: Farmers in the Midwest are hoping President Trump ends his trade war with China before their soybeans start to rot. (Binyamin Appelbaum, The New York Times)

What Is a Wave?: Democrats are in a good position to do well on Tuesday, but what, exactly, constitutes a blue wave? Sean Trende explains. (Real Clear Politics)

VisualizedHealth Care, Taxes, or Jobs?: Which are the most commonly discussed issues in your state? Check out this map. (Demetrios Pogkas and David Ingold, Bloomberg)

Sometimes it seems like Democrats and Republicans aren’t even speaking the same language. But when it comes to online advertising, there are some surprising similarities between the big topics for both parties.

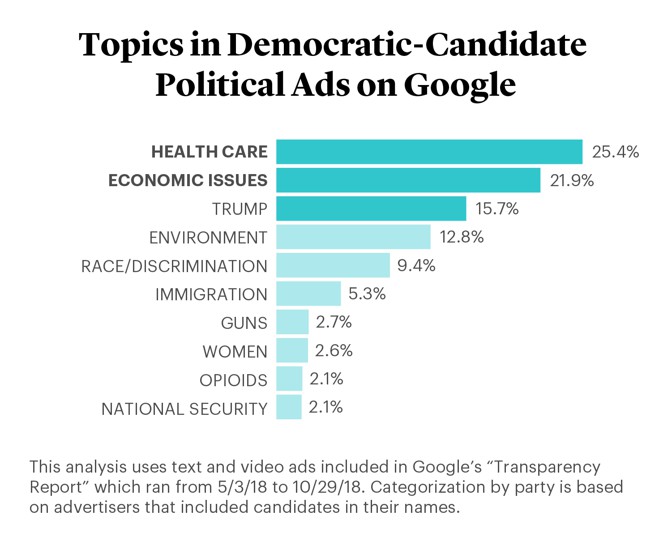

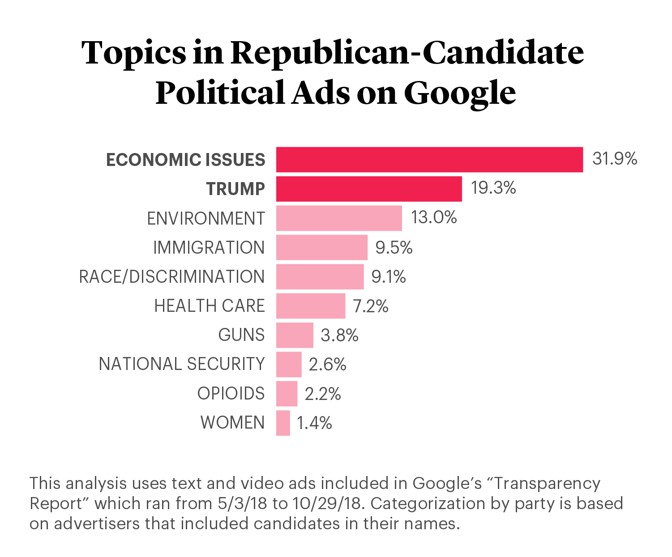

The topic mentioned most often in Democratic ads on Google, according to an Atlantic analysis, is health care—which lags well down among the Republican topics. But the next two leading Democratic subjects are economic issues and President Donald Trump, similar to the Republican results. The figures are derived from an analysis of Google’s “Transparency Report,” which collects advertisements run on Google Ad Services, the largest online advertising platform. The numbers cover any actor who has spent at least $500 on ads, including candidate campaigns, party political-action committees, and independent advocacy groups.

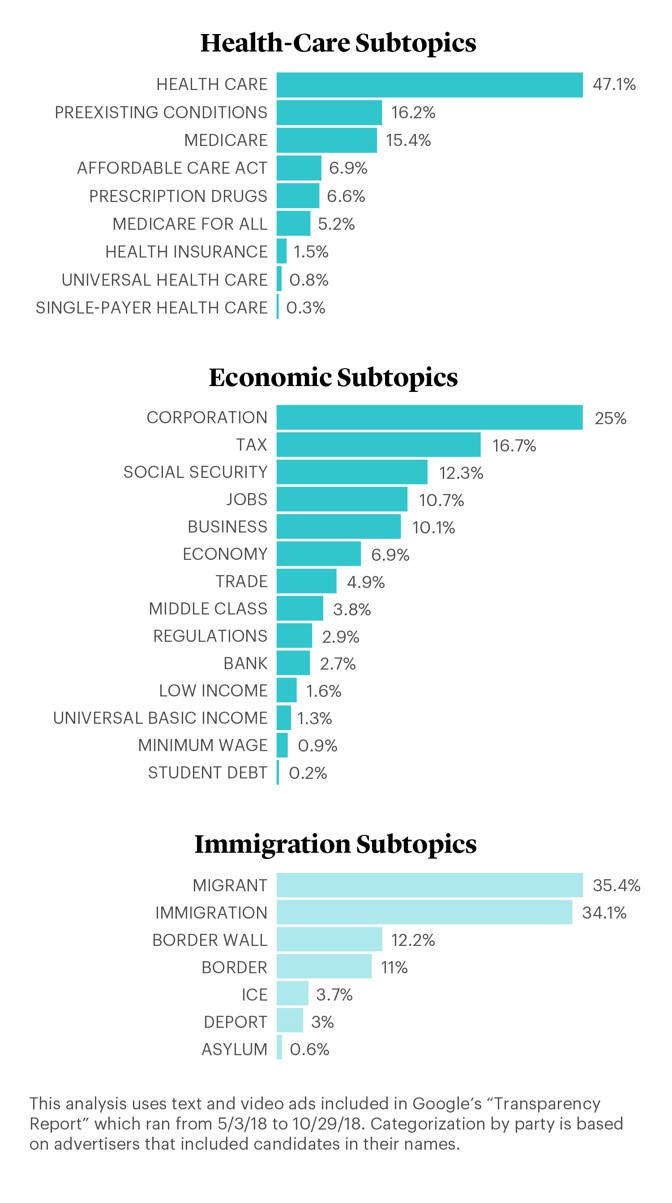

The Democratic focus on health care, at roughly a quarter of ads run, is not surprising. As Annie Lowrey reports, the party has found health care to be a potent issue in the midterm elections, pointing to numerous Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Notably, a significant share of the ads about health care focus on preexisting conditions, a reference to Obamacare’s most popular provision. Despite their claims to the contrary, Republicans have sought to eliminate the measure, which guarantees that people with preexisting conditions can obtain insurance.

The next two issues, the economy and Trump, are a little more unexpected. Although Democrats are quick to note that economic gains are not widely distributed, most standard indicators point to a strong economy, from stock-market gains to job growth to wage increases. Traditionally, a strong economy favors the party that controls Congress and the White House. But Republicans have struggled to turn that good fortune into an effective messaging tool, and Democrats are running on the issue as well.

It’s the focus on Trump that’s most interesting. Sixteen percent of Democratic Google ads mention Trump, barely lower than the 20 percent of GOP ads that do. As NBC News reported, based on a Wesleyan University analysis of broadcast spots, Trump was surprisingly absent from Democratic ads on TV from mid-September to mid-October, appearing in just one in 10. (What’s more, only half of those were negative.) Online, it’s a different story, with Trump emerging as a major theme.

Given that Republicans are on the defensive on health care, and that Obamacare has grown more popular as it’s been on the chopping block, it stands to reason that it would be a more minor topic in GOP-placed ads—appearing in just 7 percent of them.

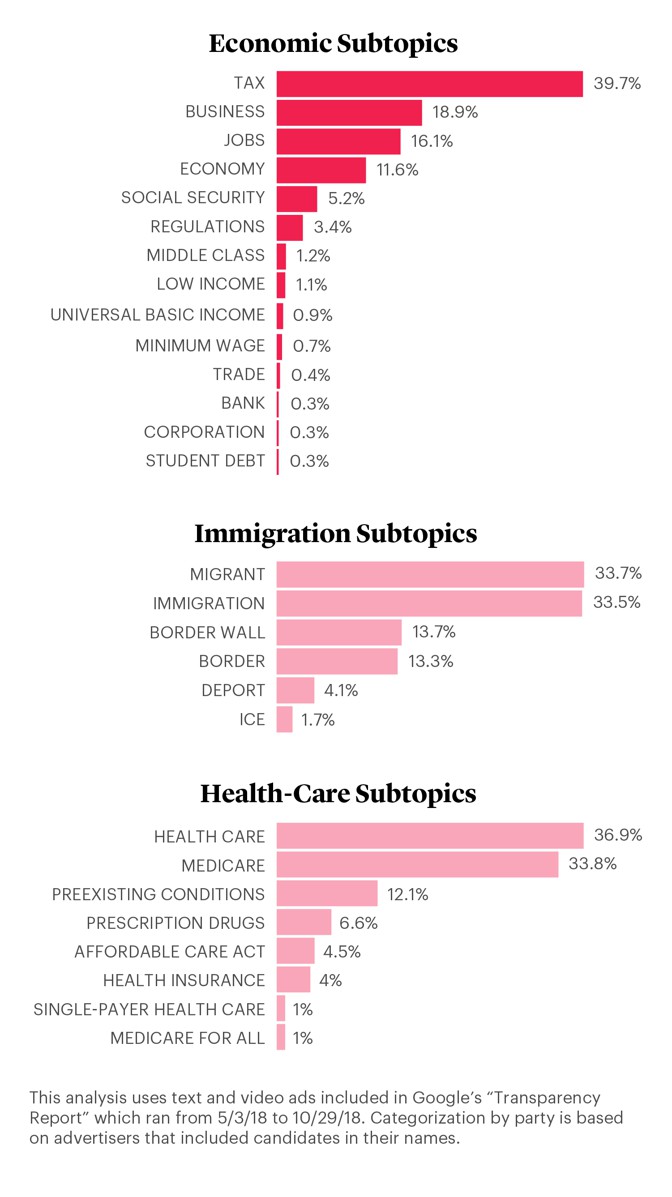

Republicans are seeking to capitalize on the positive economic news. Far and away the biggest economic topic is taxes. Late last year, the Republican-led Congress passed a large series of tax cuts, which they hoped would give the party a boost in the midterms. But those cuts have proven unpopular with voters.

The reasons for that are complicated. But surely one reason that the economy isn’t lifting Republicans as much as they’d like is the next biggest subject of ads: Donald Trump. The president remains unpopular and divisive, and Republican candidates for office have had to wrestle with how to deal with that. One option is to try to distance oneself from the president and appeal to voters turned off by him. But that’s a tactic that often comes up short—just ask the Democrats who tried to keep former President Barack Obama at arm’s length in 2010 and found themselves jobless. The second option is to embrace the president and hope that enthusiasm among Trump fans balances out the disadvantages.

What’s missing from advertising can be as telling as what’s there. Just 10 percent of Google ads from Republicans deal with immigration, even though Trump has tried to make it the focus of the campaign in the closing weeks. Republican candidates and their allies seem less eager to embrace that debate, perhaps reflecting the reality that Trump’s immigration views are not especially widely shared.

For the first four days of November, the streets of Toulouse, France, were transformed into a performance space for the massive robotic puppets Ariane and Asterion. The giant spider and 50-ton Minotaur were featured in the French street-theater company La Machine’s multiday show Le Gardien du Temple. Live music accompanied the giants as La Machine performers guided them through the “labyrinth” formed by the streets of Toulouse. Here, from the Agence France-Presse photographer Eric Cabanis, a few shots of the show and some of the more than 600,000 audience members.

In the fall of 2015, while rummaging through the fossil collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Matthew McCurry came across a very strange skull. It belonged to an extinct dolphin named Eurhinodelphis, and it was incredibly long. The braincase was only slightly bigger than McCurry’s outstretched hand, but the snout stretched farther than his entire arm. “I was amazed that something could have a snout that long,” he says.

Today’s oceangoing dolphins have snouts on the short side, ranging from the flattish bumps of orcas to the, er, bottle noses of bottlenoses. River dolphins like the Amazonian boto or the Ganges susu have much more distended snouts that can be almost twice as long as the rest of their skulls. But Eurhinodelphis’s snout is five times longer than its braincase. It looked like a dolphin that was trying to do an impression of a swordfish, or perhaps one that had told one too many lies. For good reason, its name literally means “well-nosed dolphin.”

McCurry, a paleontologist who normally works at the Australian Museum, found many similar species of dolphins within the Smithsonian’s vaults. Parapontoporia. Xiphiacetus. Zarhinocetus. Zarhachis. Pomatodelphis. All had long snouts, and some had more teeth than any other mammal on the planet—up to 350 in some species. “People have been describing these species for a long time,” says McCurry, “but no one’s really gone further than naming them and noting that they have a long snout.”

In these bizarre skulls, McCurry saw a mystery. Many aquatic animals, from river dolphins to gharial crocodiles, have evolved long, toothy snouts to help them catch fish. But why did these particular dolphins take their snouts to such an extreme? In a curious twist, these species weren’t all part of the same lineage. Rather, they evolved from short-snouted ancestors on at least three different occasions, all during the Miocene period between 5 and 23 million years ago. “There must have been something going on in their environment at the same time to drive their evolution,” says McCurry.

To work out what that was, he first had to understand how these animals used their snouts. Working with Nick Pyenson, the Smithsonian’s expert on prehistoric whales, McCurry used a medical scanner to create digital models of the skulls of several long-snouted dolphins. He then analyzed those models with techniques that engineers use to measure the strength of beams and girders.

He found that the dolphins could easily have swept their snouts through the water at high speed, stunning fish in the way that modern billfishes like swordfish do. The different species likely used different techniques. Some, like Zarhachis, had flattened snouts, and probably swept the water from side to side at stunning speeds, just like today’s swordfish. Others, like Xiphiacetus, had snouts that were circular in cross section; like today’s marlins, they sacrificed a bit of speed for the ability to attack in any direction.

Crucially, these long-snouted species arose during a time in the middle of the Miocene when ocean temperatures started climbing. In cold water, warm-blooded predators like dolphins have an advantage over cold-blooded prey like fish or squid, because they’re better at maintaining a high metabolism and swimming at high speeds. As the oceans warm, fish can move faster and the dolphins’ advantage disappears. Perhaps some of them regained the upper hand by evolving long snouts that could swiftly sweep through shoals of prey.

[Read: In a few centuries, cows could be the largest land animals left]

During the mid-Miocene, sea levels also rose, flooding the shorelines and creating a variety of new shallow habitats. This varied coastal world effectively gave dolphins permission to be weirder. Some evolved massive underbites and perhaps used their lower jaws to skim through mud. Others developed walrus-like tusks, which they could have used to extract buried shellfish. And still others, of course, evolved extremely long snouts.

But this extraordinary period of evolutionary experimentation ended when the Miocene gave way to the Pliocene. Temperatures fell, the climate became more erratic, and the planet entered into a series of cycling ice ages. Creatures that evolved during the more stable climatic heyday disappeared. “That explains why we don’t have these weird, long-snouted dolphins around today,” says McCurry.

Studies like these are important because they highlight how the shapes of animals are shaped by their environment, and how much diversity can be lost when that environment changes, says Karina Amaral from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, who was not involved in the study. “At a time when many people insist on ignoring our changing climate,” she adds, this kind of research can help to paint a clear—and concerning—image of the consequences.

Donald Trump has a habit of taking to Twitter first thing in the morning. So when he fired off a slew of tweets early one late-October morning, it wasn’t much of a surprise. “In Florida there is a choice between a Harvard/Yale educated man,” Ron DeSantis, he wrote, before vilifying DeSantis’s opponent, Andrew Gillum, who is vying to become the state’s first black governor, and just the fifth black governor in U.S. history.

Trump’s tweet was an example of the time-honored tradition of equating an Ivy League degree with a person’s bona fides for a position. But Gillum had a reminder for the president. “I am a graduate of THE Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University (FAMU),” he responded the next day on Twitter. “An HBCU founded on October 3, 1887. Google it.”

[Read: Andrew Gillum is Florida’s homecoming king].

The exchange was interesting not least because the Trump administration has made a show of courting historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs. And despite a number of public missteps, it has consistently pointed to its work with black colleges as one of its “wins” with the black community. These institutions, which were founded primarily after Reconstruction to educate black Americans who had been shut out of the rest of higher education, have had their fair share of struggles over the past few decades—budget woes, enrollment dips, and accreditation concerns among them. But they have seen a renaissance, of attention and enrollment, in the Trump era.

Another, perhaps unforeseen renaissance, however, has been the rise of black politicians who graduated from these colleges. In addition to Gillum, Stacey Abrams, a gubernatorial candidate in Georgia, and Mandela Barnes, a candidate for lieutenant governor in Wisconsin, both attended historically black colleges. The prospect of so many black-college graduates being elected to statewide office in the same year is unprecedented, Keneshia Grant, an assistant professor of political science at Howard University, told me.

Now, of course, there are HBCU alums across all levels of government. Senator Kamala Harris graduated from Howard University, and the mayors of Atlanta, New Orleans, and Birmingham—all of whom were elected in 2017—also attended HBCUs. And there have previously been governors who attended black colleges: In 1989, Douglas Wilder became the governor of Virginia and the first elected black governor in the United States. In the 1870s, there was P. B. S. Pinchback, who very briefly served as the governor of Louisiana. These candidates—Abrams, Gillum, and Barnes—are continuing that black political tradition.

[Read: Stacey Abrams’s prescription for a maternal-health crisis]

However, just as the sheer number of these candidates is different, so too is the energy behind them, particularly for Abrams and Gillum, says Grant—and it’s making them more popular with students at HBCUs. The politicians are vocal in boosting black colleges. They’re celebrities at homecoming. And they’re unyielding in their clap backs during debates.

“It changes the students’ engagement with the materials for the [candidates] to look like them and quote Migos. If you show a clip of a person who is a legitimate candidate who is good on policy and can talk about ‘walking it like he talks it,’” alluding to the viral clip of Gillum that references the lyric from the rap group Migos, “it just takes the lesson [in class] to another level.”

Abrams, Gillum, and Barnes are sending a message, says Walter Kimbrough, the president of Dillard University, an HBCU in New Orleans. “It’s a reaffirmation, not only for students but for families, that you can go to an HBCU and compete with anyone.” Kimbrough told me it’s important not only that the candidates attended a historically black college, but also that they’ve embraced it as a fundamental part of their identity.

And the candidates are taking up the mantle of defending black colleges as important institutions, he says. For instance, when Representative Cedric Richmond criticized Senator Bernie Sanders’s education plan for not mentioning HBCUs, Abrams tweeted her agreement: “HBCUs are vital for economic independence,” she wrote. And the institutions, which have struggled across sectors, both public and private, could use the boost.

While it’s unclear whether these black politicians will pull out victories tomorrow, their candidacies could still prove important for HBCUs. “I always tell people you can go wherever you want to go,” says Kimbrough. “We want people to go where there’s a good fit. But don’t just assume because the person went to an HBCU that they aren’t as good.”

Carly Simon summed up the musical subgenre of tunes about famous lovers with her 1972 riddle of a chorus: “You’re so vain, you probably think this song is about you.” When singers of breakup songs drop hints but don’t drop names, what is the listener to do but speculate? As tabloid media and the internet have intensified such guessing games, the art of the subtweet has only become more important, as seen in the career of Taylor Swift.

But Ariana Grande—perhaps taking inspiration from her far franker friends in hip-hop, like the frequent namer-and-shamer Nicki Minaj—is done being coy. Already, on her latest album, Sweetener, she broke with pop’s imperatives toward vagueness by titling one song “Pete Davidson,” after the SNL comedian she was then engaged to. Their relationship at that point was as intense as it was new, and perhaps accordingly, the song lasted only a little more than a minute. Grande rapped about him being her soulmate, and then violins joined in as she faded out, singing, “Gonna be happy, happy / I’ma be happy, happy.”

Alas, that relationship disintegrated in October. The breakup added to the list of meta-musical reasons to talk about (and maybe even pity) Grande following the terrorist attack at a 2017 concert of hers and the sudden death of the rapper Mac Miller, her most recent ex. Amid such setbacks, Grande has all along made a show of public resolve rooted in joie de vivre: Her bottom line is that love heals all. With one new single, she’s added a tough edge to that message—highlighting her ownership of not only the gossip, but also her romantic life, her growth as a person, and her career as a maker of catchily inspirational bops.

That song, “Thank U, Next,” appeared online Saturday night, and it’s got a doozy of a first verse. As reverberating chimes conjure a fairy-tale atmosphere, Grande sings:

Thought I’d end up with Sean

But he wasn’t a match

Wrote some songs about Ricky

Now I listen and laugh

Even almost got married

And for Pete, I’m so thankful

Wish I could say, “Thank you” to Malcolm

’Cause he was an angel

It’s a list of former lovers: the rapper Big Sean, the backup dancer Ricky Alvarez, Davidson, and Miller. One taught her “love,” one taught her “patience,” one taught her “pain,” she sings as she locks into a suspenseful melody. Then comes the fluttery, immediately catchy chorus. “Thank you, next,” Grande repeats, eventually arriving at a descending, carefree trill: “I’m so fucking grateful for my ex.”

This all might read as sarcasm, setting up a diss-y or dishy elaboration on the names mentioned in the first verse. But instead, Grande begins to sing about meeting someone new: “Her name is Ari.” With that, the point of the song is revealed to be the opposite of what it initially appeared to be. It’s about Ariana Grande, not Ariana Grande’s guys. Love, patience, and pain—all self-taught lessons, too.

This is a feminist rewriting of the public narrative—about a woman defined by, and perhaps even brought down by, men—pulled off with lightness. The vibe is sly and swinging; a high hat in the chorus makes like a drum crash during a stand-up roast. In the bridge, she envisions her wedding, at which she wants to have her mom by her side (“I’ll be thanking my dad / ’Cause she grew from the drama,” she sings, presumably referring to her parents’ divorce during her childhood). She only wants to get married once, but if “God forbid something happens,” she shrugs, at “least this song is a smash.” Very deft: classic pop romanticism, cut with shit happens realism, spiked with trendy swagger-as-empowerment.

The timing was deft, too. Last week, Grande criticized Davidson for joking about their breakup publicly, but this song—released minutes before SNL aired on Saturday—takes the lyrical high road. On “Weekend Update,” the perhaps chastened Davidson made a bland statement about him and Grande’s situation being “nobody’s business.” But Grande’s song acknowledges that it has become, for better or worse, everybody’s business—and insists that it’s going to be so on her own terms. Breezy and bold, “Thank U, Next” puts the gossip in perspective: However long her relationships have lasted, her life is a lot bigger than them.

“Major League Baseball has long been losing its grip on the title of America’s pastime,” Hayley Glatter wrote after the Red Sox won the 114th World Series. The game, she argued, is too long, lacks star power, and has been cannibalized by its crushing quest for metrics.

As a die-hard baseball fan, I think this is a great article. Baseball is genuinely at war with itself to keep the elements that its casual appreciators enjoy without sacrificing what its die-hard fans enjoy—at some point, it may just need to pick a side. I think it should probably pick the casual side: There are more casual fans, and diehards like me are just committed enough to grin and bear it.

But anyone who’s trying to get into the Red Sox specifically and struggles to because of the team’s “lack of a transcendent star” is defining “transcendent star” as someone who is as talented and famous as LeBron James, Michael Jordan, and maybe Tom Brady, if I’m feeling generous. If Mookie Betts isn’t meeting your criteria, I feel they are unreasonable criteria. He’s probably the second-best player in baseball, he’s charming, and he’s young, with his best possibly still ahead. Mike Trout would meet the criteria as well if he weren’t such a dud of a personality. Francisco Lindor is another strong candidate, though the smaller market won’t help him. Aaron Judge is a striking dude who smashes dingers.

Pace of play, confusing rules, hyper-granular managing and analytics, sure. But lack of star power is not something it looks like the MLB has to worry about.

Kyle Dawson

Brooklyn, N.Y.

I must respectfully and vociferously disagree with your assessment of the baseball played in this 2018 World Series—it has been nothing short of captivating.

Yes, I am a lifelong Red Sox fan, but even more than that, baseball has been a lifelong love (as it is for my 13-year-old and so many girls and boys and men and women I know). I found the series entirely transporting. And I’m convinced I am no outlier. The pitching and hitting were so brilliant, so evolved—and the margin for error so small, and consequences so large—that each pitch of every at bat was its own enthralling odyssey.

I’m a far cry from a baseball expert, but even I can see how the game is evolving in particularly evocative ways these days. I can’t avert my eyes from each pitch and swing. There are reasons it took more than seven hours for a team to emerge victorious in Game Three. Just as there are reasons home runs so often now dictate wins and losses. Even I can appreciate just how high the level of play has been—from pitch location and movement to swing speed and trajectory. It has been incredibly exciting.

To steal a line from the iconic Field of Dreams, I respectfully suggest: Perhaps if you’d experienced even just a little bit of what I see in the game of baseball these days, maybe you’d love it too.

Susan Gerson

Washington, D.C.

I agree with the author’s assertion that the game needs to be sped up. Here is how to do it:

1. Decide on a reasonable amount of seconds between pitches.

2. If, by that time, the batter is not ready to hit, call a strike.

3. If, by that time, the pitcher has not thrown the pitch or to a base to hold a runner, call a ball.

4. Each team may stop the pitch clock with a limited number of time-outs.

Baseball’s problem solved. You’re welcome!

Bob Tewes

Sandwich, Mass.

I consider myself a die-hard Red Sox fan and watched as many games as I could in the 1970s and ’80s. Today, not so much. For me, the biggest turnoff is player turnover. Only one member of the 2018 team played on the 2013 World Series team. I have a hard time relating to the constant coming and going of players.

Rick Conlon

Brandenton, Fla.

This age of lies, greed, haste, superficiality, inequality, and partisanship may be properly represented by the NFL, but give me baseball every time. As the temperature goes down and we start driving home from work in the dark of winter, I already miss baseball. I look forward eagerly to next year. Leave my sport alone.

Edward J. Szewczyk

Belleville, Ill.

I don’t know what to do except bemoan the fact that baseball just doesn’t seem well suited to today’s internet-shortened attention spans.

I sat through all 18 innings of Game Three and loved it! But then, I’m a grouchy old fart.

I will say that baseball’s current obsession with analytics reminds me of how bland, poll-tested politics has robbed that sphere of its vitality. And the unfettered greed of everybody in the sport is disheartening. I’d go to a lot more games if a beer didn’t cost so much.

One technical change that could improve the game: Move the fences back. MLB evidently thinks that fans demand lots and lots of home runs, but when every batter comes to the plate swinging for the fences, a lot of the game’s complexity and beauty is lost.

Rob Lewis

Langley, Wash.

I’m 61 and a lifelong baseball fan. Each October, I watch the World Series and am almost always satisfied. The Series doesn’t need the hype that always seems to surround the Super Bowl or NBA finals; the night games, the October chill, the faces of the players and managers in the dugouts are all compelling to me.

I admit that there are more pitching changes than I’d like, but one reason that teams such as the Red Sox, Yankees, and others play long games—which is a testament to their success—is that their hitters are patient and make pitchers work deep counts. The game lasts longer because of that, but I don’t see this as a flaw of the game itself.

I agree that the four wild cards have been an asset to the game, but I’m afraid that I don’t see eye to eye with you on limiting extra innings, on lamenting the lack of star power (another satisfying element of many past World Series has been watching a Steve Pearce or a Mark Lemke get locked-in and lift their team when the stars aren’t quite getting it done), or that we need a “livelier” version of the game. Perhaps I’m in the minority, but I just don’t see how this Series was bad for the game.

Mike Canning

Oak Park, Ill.

The article left out a major reason for declining attendance and viewership of major sporting events in general: the cost of tickets and media to view them.

Steve Rova

Lincoln City, Ore.

Playoff baseball is a “dreadful chore,” according to Hayley Glatter. No, the recent World Series was lots of fun: The 18-inning game that could have turned the tide for the Dodgers but didn’t; the clever pitching strategies by the Red Sox manager Alex Cora; the joyful home-run trots; the unexpected heroes. Fans, regardless of their loyalties, were privileged to witness one of history’s best baseball teams slug, throw, and think its way to victory. Great stuff for those who love the sport.

Jim McMahon

Honolulu, Hawaii

Patience and a respect for the past. This is what baseball has to offer the contemporary world, a valuable counterweight to the instant gratification and worship of the new that diminish modern life.

Yes, small tweaks can be made to improve the pace of play. But perhaps we should acknowledge that baseball is no longer and will not return to being America’s game (or Canada’s, for that matter); that it will have fewer fans as time goes on; and, that there will be less money made and fewer millionaire players. So what? Does everything have to be measured in terms of popularity and money? The cancer in our economic system is the fundamental assumption of growth. It will consume the planet and kill us all. Maybe growth isn’t the answer for baseball, either. Keep the game the same, settle for fewer fans, and manage the steady state instead of championing the malignancy of constant growth. Some say that baseball is a great metaphor for life. Perhaps, in settling, it can be a sobering metaphor for our collective future as well.

Brian Green

Thunder Bay, Ontario

Been following the Red Sox since the 1950s, and if it wasn’t for a DVR, I wouldn’t have seen the playoffs. How do you attract young fans when the pace of the game is mind-numbing, and the late starts east of the Mississippi make it impossible for them to stay up? This also includes old guys like me and most of the workforce. May not be as much fun as watching live, but next-day watching is less stressful.

Kevin O’Neil

Franconia, N.H.

8:15 p.m. EST is far too late for baseball to start.

Cassie Julia

Waterville, Maine

If you don’t like baseball, don’t watch baseball. That seems far more logical to me than trying to change baseball to appeal to people who don’t like to pay attention to anything anymore. Short attention spans and reality-television addiction are negatives, and certainly not things that should be enabled on a national level at the expense of a game that is nearly 150 years old.

Personally, I don’t watch much tennis, soccer, or darts. But I certainly don’t want any changes to be made to those games on my behalf. Just play on without me.

David Pye

Montreal, Quebec

I agree that something needs to be done about the pace of the game—maybe borrow another page from tennis, which recently instituted a “serve clock,” and institute a “pitch clock.” Another problem plaguing baseball is how the networks show the product. The majority of what is shown on TV is rotating close-ups of four things: the pitcher, the batter, someone spitting in a dugout, and random fans. How about swapping out one of those last two for a shot of the whole field?

John H. Campbell

Portland, Ore.

Jennifer Pelot Rysewyk wrote: Or, maybe it was because these were two big market teams with bloated salaries. Analytics aren’t killing this game. Neither is the duration of nine innings. It’s knowing if you don’t follow a large market team that can afford to rent the best players, you won’t have a chance. Until legitimate salary caps are in place, it’s just going to get worse.

Gayle Mills writes: Loved watching the games but I really wish that some of the games were during the daytime. This is for my grandson who would have loved to watch a game. Come on MLB !!!

Hayley Glatter replies:Make no mistake: The 2018 Red Sox were an incredibly talented and entertaining team. The two games I caught at Fenway Park this season were captivating and dramatic, and there’s nothing quite like spending an evening in the glow of Boston’s Citgo sign. Despite its skill level, however, I argued in this piece that the team is without a transcendent star. A lot of readers, Kyle Dawson included, disagreed with this assessment and pointed specifically to Mookie Betts as a counterexample. Betts is an undoubtedly dynamic player and, at just 26 years old, likely has many productive seasons ahead of him. But being a great ballplayer doesn’t necessarily mean he’s catching the attention of casual fans outside of New England.

Though it’s an imperfect measure of fame and influence, Betts has just 582,000 Instagram followers and 180,000 Twitter followers. The 76ers center Joel Embiid, meanwhile, has 3 million Instagram followers and 1.55 million Twitter followers; and the Giants running back Saquon Barkley has 1.3 million Instagram followers and 240,000 Twitter followers. Neither Embiid nor Barkley is the most famous player in his sport. But both are younger than Betts and have stronger name recognition than he does. Baseball players today are not any less talented than those who played in the past, but the sport is in a transition period as athletes like Betts and the Yankees’ Aaron Judge establish themselves. For now, the game is without a magnetic standard-bearer who can successfully energize casual fans and motivate them to turn on a game that their team isn’t playing in. Perhaps in a few seasons, Betts will be as prominent a household name in Boise as he is now in Boston. But it won’t happen overnight.

SAN DIEGO, Calif.—Congressman Duncan Hunter had a problem.

The California Republican was supposed to coast to reelection this year. A square-jawed ex-marine who inherited his father’s House seat in 2008, Hunter had won each of his past five elections by a wide margin. His district, a collection of inland San Diego suburbs, was solid GOP territory, and few campaign watchers expected that to change anytime soon.

But then Hunter got indicted.

On August 22, federal prosecutors charged the lawmaker and his wife with stealing $250,000 in campaign funds. In a 47-page indictment littered with galling details, the Hunters were accused of using campaign cash to fund lavish family vacations; to pay for groceries, golf outings, and tequila shots; and even to fly a pet rabbit across the country. To cover their tracks, the indictment alleged, the Hunters often claimed that their purchases were for charitable organizations like the Wounded Warrior Project.

The political backlash was swift and severe. Hunter was stripped of his committee assignments in the House. His fund-raising dried up, and Democratic money flooded into the district. When he tried to defend himself on Fox News, he exacerbated the crisis by appearing to pin the blame for the scandal on his wife.

[Read: Duncan Hunter’s indictment is a threat to the GOP House majority.]

Publicly disgraced, out of money, and facing both jail time and a suddenly surging challenger—what was an indicted congressman to do?

Eventually, Hunter seemed to arrive at his answer: Try to eke out a win by waging one of the most brazenly anti-Muslim smear campaigns in recent history.

In the final weeks of the election, Hunter has aired ominous ads warning that his Democratic opponent, Ammar Campa-Najjar, is “working to infiltrate Congress” with the support of the Muslim Brotherhood. He has circulated campaign literature claiming the Democrat is a “national security threat” who might reveal secret U.S. troop movements to enemies abroad if elected. While Hunter himself floats conspiracy theories from the stump about a wave of “radical Muslims” running for office in America, his campaign is working overtime to cast Campa-Najjar as a nefarious figure reared and raised by terrorists.

As multiple fact-checkers in the press have noted, these smears have no basis in reality. Campa-Najjar—a 29-year-old former Barack Obama aide who is half-Latino, half-Arab—is a devout Christian who received security clearance when he worked in the White House. His grandfather was involved in the massacre at the 1972 Munich Olympics, but he died 16 years before Campa-Najjar was born, and the candidate has repeatedly denounced him.* (Growing up, Campa-Najjar became estranged from his father, a former Palestinian Authority official, and was raised primarily by his Mexican American mother.)

But facts do not appear to be Hunter’s chief concern. The political strategy here is self-evident: Feed on anti-Muslim prejudice to scare enough conservative voters into pulling the lever for the incumbent—indictment be damned.

California’s Fiftieth District hasn’t drawn much attention from horse-race obsessives this year. There are other races with tighter polls, other House seats more likely to flip. But what’s unfolding here in the suburbs of San Diego represents an unnerving microcosm of this campaign season: white Republicans frightened by cynical conspiracy-mongers; religious minorities frightened by the fallout; a community poisoned by Trumpian politics—and a bitter question hovering over the whole ugly affair: Will it ever get better?

Duncan Hunter is not an easy man to find these days. He rarely holds campaign rallies, and doesn’t attend town halls or debates. When I emailed his office asking for an interview, I was politely told my request would be added to the “list”—and then ignored when I tried to follow up.

Recent polls have shown that around half of the voters in Hunter’s district are sticking with him. But finding surrogates to talk on Hunter’s behalf proved as daunting as nailing down the candidate himself. Emails, phone calls, and Facebook messages to local conservative groups went unreturned. Not even Hunter’s former GOP primary challenger had nice things to say: Shamus Sayed, a Muslim businessman and longtime Republican, told me he found the congressman’s mudslinging “pathetic,” and that he planned to vote for “anyone but Hunter.”

To find an outspoken Hunter supporter, I turned to the land of the professionally outspoken: conservative talk radio. In a nondescript office building just outside La Jolla, I met Andrea Kaye, a drive-time host whose show is beamed out across San Diego County each night. A Louisiana transplant who bills herself on air as “dynamite in a dress,” Kaye takes pride in having her finger on the SoCal conservative pulse. I found her in the KCBQ studio preparing for her show. She wore big, gold hoop earrings and sipped from a mug made to look like a stack of frosted donuts.

Kaye blamed a climate of militant political correctness for Hunter’s lack of vocal boosters in the district. “It’s the ultimate bullying,” she complained. “You’re not allowed to ask questions about [Campa-Najjar] or you’re going to be called Islamaphobic.”

And that pesky indictment? The charges were troubling, she admitted. “But I always say, Innocent until proven guilty.” She’s been urging her listeners to reelect Hunter and then let the chips fall where they may once he’s back in Washington.

[Read: Democrats want to flip six seats in California.]

Kaye told me Hunter had likely been helped by a recent controversy that provided an important local backdrop to the current congressional race. Earlier this year, a group of parents sued the San Diego school district over an anti-bullying initiative aimed at creating “safe spaces” for Muslim students. Predictably, the lawsuit became a rallying point for right-wing culture warriors, who claimed the program—which included adding Muslim holidays to the calendar and teaching Islamic culture as part of the social-studies curriculum—was actually an effort to indoctrinate children with Islamist propaganda and make their schools “Sharia-compliant.”

While Kaye conceded that Hunter’s campaign probably went too far by labeling his opponent a “national security threat,” she insisted it was only natural for voters to demand serious scrutiny of Campa-Najjar’s background.

“There are multiple fronts of jihad,” she told me, her voice taking on a grave tone. “One is jihad through the sword, and the other is creeping Sharia.”

Hunter is not the only politician in America trying to win an election with Muslim-bashing. A recent report by Muslim Advocates, a civil-rights group based in Oakland, California, named 80 office seekers in federal, state, and local races across the country this year who have expressed anti-Muslim sentiments. (All but two are Republicans.)

The report’s author, Scott Simpson, told me Donald Trump—who made hostility to Muslims a centerpiece of his presidential campaign, going so far as to declare, “I think Islam hates us”—seems to have inspired a legion of copycat candidates in 2018. “There’s been this sort of wave of anti-Muslim candidates who are making the calculation that now is their time,” he said.

Simpson said some of these people are acting on bone-deep bigotry, while others are simply opportunists. But even if their stump screeds come off as “shrill and out of touch with reality,” he cautioned against ignoring them outright. “There’s a very coherent story that’s being told about Muslims … that’s actually really sophisticated.” At the core of this story, he said, is the idea that Islam is not really a religion, but a violent political ideology whose adherents want to take over the government and replace the Constitution with Sharia law. Simpson told me that of all the candidates he has tracked this year, Hunter is the one who has “most fully digested the conspiracy theory, and is repeating it back.”

Simpson was quick to point out the silver lining in his report: Of the 80 candidates he wrote about, only 12 are safely projected to win their election. According to the organization’s polling data, the vast majority of voters—including many conservative Christians—are put off by politicians who attack Islam. “This isn’t a winning strategy,” he said.

And yet, whether they win or lose, these candidates can end up leaving a trail of collateral damage in their communities. The Muslims I interviewed in Hunter’s district still remember how they felt the day candidate Trump called for a travel ban on their coreligionists. They remember the rabid cheers from his supporters, and the wall-to-wall coverage on TV, and the sinking dread they felt as he proceeded to climb in the polls.

“It was scary,” said Ellen Molla, a Muslim mother of three who lives in Escondido. “It was kind of a shock that there were so many people that supported that. In everyday meetings, I would never have guessed that my neighbors next door had a problem with me.” After Trump, though, she began to suspect they might.

Tasir El-Quolaq, a former U.S. federal agent who served in Iraq, has been registering Muslim voters in the San Diego area for years. But since Trump’s election, he’s noticed that some people at his local mosque are simply disengaging from politics. They feel like the process is rigged against them—and Hunter’s recent smear tactics have only added to the exhaustion. “We are always on the defensive,” El-Quolaq told me. “Always.”

[Read: The proud corruption of Donald Trump]

Meanwhile, the Islamaphobia on display in the modern GOP has been especially frustrating to Muslims who are politically conservative. “When we first came here, most of us sort of favored the Republican Party,” said Mohammed Kasabati, a retiree from Pakistan who moved to the U.S. decades ago. He noted that many Muslim voters hold socially conservative views, and belong to higher income brackets. In 2000, about 70 percent of them supported George W. Bush—and Kasabati still remembers the way that president defended the Muslim community in the wake of 9/11. Of course, Bush went on to lose Muslim support in the years that followed, with policies like the Patriot Act, which made it easier for the government to surveil Muslim Americans, and the war in Iraq. But Kasabati still thinks there could be a place in the GOP for people like him—if only Trump and his imitators would stop vilifying their faith.

“This is a country that was founded by people fleeing religious persecution,” Kasabati said. Was it really too much to ask that the party of religious freedom extend them the same courtesy now?

On a warm night in October, about 80 students gathered in a softly lit auditorium at the University of San Diego to hear Ammar Campa-Najjar and other panelists offer advice for minorities entering politics.

After weeks of pitching himself nonstop to Trump voters in his deep-red district, Campa-Najjar had built up a collection of cringe-inducing encounters—and now he seemed eager to unload them. He talked about the man who refused to shake his hand and called him a terrorist, about the supporter who suggested he shave his beard so he wouldn’t look so much like a terrorist. As he spoke, I wondered just how much time he’d been forced to spend on the campaign trail assuring voters that he didn’t want to kill them.

[Read: How American Muslims are trying to take back their government]

These interactions had clearly made him hyperalert. Even here—at the kind of event where he could comfortably riff on “toxic masculinity,” and get away with saying things like, “Fellas, we need to be more woke”—he couldn’t quite let his guard down. When another panelist said something about raising an “army” of allies, Campa-Najjar’s ears perked up. “See,” he cracked, “that’s something I could never say.”

After the event, we went outside and took seats at a table in the courtyard. Campa-Najjar looked every bit the well-coiffed congressional candidate—shiny hair, dark suit, flag pin—but he also exuded a kind of underdog exhaustion. I told him he looked tired. He told me he was.

The attacks of the past few weeks had left him indignant, but also darkly amused. He joked that if an Islamic terrorist ever actually encountered the two candidates together, he would likely take out the ex-Muslim apostate first. And for all the nonsense about Campa-Najjar being a potential “security threat,” he noted it was Hunter—the one under indictment—who couldn’t obtain a security clearance.

On the whole, Campa-Najjar said he was surprised by how ham-fisted Hunter’s strategy had been. “I thought there would be more finesse to it,” he told me.

Now, though, he was more confident than ever that victory was at hand. With Obama-esque audacity, he began ticking off all the reasons to be optimistic. The district was more diverse than many realized. “McCain Republicans” were repelled by the Muslim-bashing. While his own campaign was infused with idealism and “youth,” Hunter’s was cloaked in the stench of “desperation.”

Very soon, he assured me, the good voters of the California Fiftieth would reject the ugly politics that had permeated their community this year and send him to Congress.

Perhaps detecting my skepticism, Campa-Najjar tried to conjure an alternative happy ending. “And if we fall short,” he tried, “we proved that we exceeded expectations and that—” but then he stopped himself. He couldn’t do it.

“I think we’re going to win.”

* A previous version of this article mischaracterized the events at the 1972 Munich Olympics. We regret the error.

Since launching its original-film division with Beasts of No Nation in 2015, Netflix has had a single hard-and-fast rule about its movies: Subscribers never have to wait an extra second to see them. If a new project received a theatrical release, it would debut on the streaming service at the exact same time. This approach clashed with the fact that most theater chains want to screen their features exclusively. As a result, Netflix films have rarely played in cinemas, and when they do, it’s only as a nominal concession to Oscar rules that demand a theatrical release for movies to qualify for trophies.

This year, Netflix has the rights to Roma, Alfonso Cuarón’s achingly personal new epic, which is being touted for huge success during awards season. In the coming months, the company will also release the latest film from the Coen brothers (The Ballad of Buster Scruggs) and a sci-fi thriller starring Sandra Bullock (Bird Box). With those debuts, the studio’s rules are changing, signaling a potential détente between Netflix and theater exhibitors going forward. Roma will open in two theaters on November 21, gradually expand to more screens over the following few weeks, and finally hit Netflix on December 14.

For years, Netflix’s chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, has claimed that his “day and date” strategy, whereby movies get simultaneous digital and theatrical releases, is “going to be more and more accepted as part of the distribution norm.” There continues to be little evidence of that, mostly because Netflix doesn’t publicize detailed viewership data for its films. Certainly some Netflix projects, such as Dee Rees’s Mudbound and this year’s romantic-comedy hits Set It Up and To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, have made waves with critics.

But the company has some $10 billion in long-term debt and hasn’t demonstrated that its model of pumping out content is eventually going to be more stable and profitable than the current theater model. Recent years have also seen a series of public fights over the future of cinema, like Netflix’s withdrawal from the Cannes Film Festival in May over rules barring movies without a planned theatrical release in France, or public skepticism about the company from figures like Steven Spielberg and Christopher Nolan. A more sustainable compromise may have finally arrived.

[Read: What Christopher Nolan gets right about Netflix]

Roma isn’t the only Netflix film that’s screening around the United States before becoming available online. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs will be in select cinemas for one week before hitting Netflix on November 16, and Bird Box will also have a one-week window of theatrical exclusivity in December. Roma’s three-week theatrical run is an acknowledgment of the film’s impressive cinematic qualities. Cuarón designed the project to take advantage of state-of-the-art Dolby Atmos sound technology, and now cineasts will have more of a chance to enjoy that presentation in full before streaming becomes the only option.

“Seeing Roma on the big screen is just as important as ensuring people all over the world have the chance to experience it in their homes,” Cuarón said in a statement. “Roma was photographed in expansive 65 mm, complemented by a very complex Atmos sound mix. While a movie theater offers the best possible experience for Roma, it was designed to be equally meaningful when experienced in the intimacy of one’s home.”

Some other Netflix projects vying for awards this year—such as Tamara Jenkins’s Private Life, David Mackenzie’s Outlaw King, and Paul Greengrass’s 22 July—got the nominal theater release required for Oscar consideration. But because the films went online the same day, they never had any chance of making real money at the box office. Netflix has always argued for the virtues of its widespread membership; it reported that 14 million people watched 22 July in the first three weeks after the film’s debut, more than would have been possible for a big-screen release. But the company’s new strategy is an admission that staggering a movie’s theatrical and online runs can offer the best of both worlds.

This revised approach is also a concession to major artists such as Cuarón, the Coens, and Martin Scorsese (who’s working on Netflix’s The Irishman, slated for a 2019 release). These directors make their movies to be seen in theaters—that is, and always will be, an intrinsic part of the medium, no matter how fancy televisions become. It’s not just about the size of the screen or the power of the speakers, but also about being cloistered in a space where you can’t look away, pause the action, or easily distract yourself with other devices.

If Roma scoops up some serious Oscar nominations (or even wins one or more statues), Netflix’s breaking its ultimate rule will have paid off. Garnering that kind of industry prestige will draw in other desirable filmmakers as the company presses forward in its efforts to become a major movie studio. A cessation of hostilities with theaters was the first step toward that goal, but more adventurous, big-screen storytelling from great directors may come next.

At the end of October, after the New York Giants had stumbled off to their second consecutive 1–6 start, the freshman general manager Dave Gettleman posted a figurative estate-sale sign on the team’s locker-room door and challenged his fellow GMs to make him an offer he couldn’t refuse. With the October 25 deadline looming on the most hectic mid-season trade period in recent memory, Gettleman shipped Damon Harrison (an All-Pro defensive tackle playing the third year of a five-year, $46 million free-agent pact) to Detroit in exchange for a fifth-round pick in next spring’s NFL draft.

Twenty-four hours earlier, Gettleman also sent Eli Apple (an underachieving cornerback whom the Giants scooped up with the 10th overall selection in 2016) to New Orleans and yielded fourth- and seventh-round draft choices in that bargain, which pro-football followers greeted with a fair amount of head scratching at first. The longer the news lingered without a correction, the more Giants supporters and skeptics agreed: They traded away the wrong Eli.

Pity Eli Manning, maybe the least respected good quarterback there ever was. Despite his impeccable gridiron pedigree (Archie Manning, the much-beloved former Saints quarterback, is his father; Peyton Manning, the five-time league MVP and two-time Super Bowl champion, is his older brother), the 37-year-old Giants signal caller has never quite fit the role of fair-haired cornerstone to one of the NFL’s blue-blooded franchises. Who could forget how he barged into New York after a record-setting tear at Ole Miss, spurned the San Diego Chargers (the team that would pick him first in the ’04 draft), and forced one of the most consequential trades in NFL history?

[Read: The sheer absurdity of favoring Eli Manning over Peyton Manning]

From there followed four uneven seasons of drive-killing sacks and soul-crushing turnovers, each new error in judgment twisting Manning’s oft-ruddy game face into eminently meme-worthy expressions of slack-jawed bemusement. Even Tiki Barber, the Giants’ all-time rushing leader and a former teammate of Manning’s, piled on, describing one of the QB’s early attempts to take charge of an offensive meeting as “comical.”

Jump-cut to late in the 2007 NFL season: Just when it appeared as if regard for Manning couldn’t sink any lower, he led the Giants to four consecutive road playoff victories. They then defeated the unbeaten New England Patriots in Super Bowl XLII in one of the biggest upsets in sports, with Manning making the play of the game on an improvised 32-yard heave, aka “the helmet catch.” And when his time-capsule-worthy moment seemed in danger of fading from memory as the Giants missed the playoffs in the next two seasons, and Manning’s humble claim to elite quarterback status became fodder for debate, he sparked another late-season win streak and shocked the Patriots—again—in Super Bowl XLVI.

It was in the wake of this heart-stopping performance, after which Manning was voted MVP of the championship game for a second time, that the conversation around Archie’s son and Peyton’s kid brother started to shift. ESPN’s Trent Dilfer hailed the Giants’ signal caller as “the poster boy for what a Hall of Fame quarterback should be,” while Manning’s NFL peers ranked him 31st among the league’s top 100 players for 2012, after leaving him off the list entirely in previous years. Even Manning’s nagging habit of underthrowing his receivers was reframed as the reboot of a once-trendy football fashion: the back shoulder pass.

The honeymoon lasted until the 2013 season. As if throwing a league-leading 27 interceptions as the Giants missed the playoffs after yet another 1–6 start weren’t bad enough, Manning was sued in 2014 by a group of memorabilia collectors who charged him with hawking fake “game-worn” helmets and jerseys. (The case was settled out of court last spring.) That annus horribilis could have been motivation for the Giants to start making serious plans for the future; instead, they doubled down, betting that Manning could enjoy the same late-career resurgence that his brother had in Denver.

[Read: The NFL off-season is full of quarterbacks. ]

And so the Giants paired Manning with a slick new play-caller named Ben McAdoo, and for a while the two worked well together. So well, in fact, that Manning—whose accuracy and touchdown-to-interception ratio improved so dramatically over the next two seasons that the Giants re-signed him to a four-year, $84 million extension in 2015 that also included a no-trade clause—recommended McAdoo for a promotion to head coach for the 2016 season. McAdoo would later repay this loyalty by dealing Manning the most stinging humiliation of his career.

After going from 11 wins his first year as head coach to a 2–9 start in 2017, McAdoo did the inconceivable: Not only did he bench Manning—who at the time boasted more consecutive appearances in the starting lineup than any other active NFL player—but he sat Manning for Geno Smith, a dual-threat quarterback who’d already flamed out spectacularly with the New York Jets. “It’s been a hard day to handle this,” a near-tears Manning told reporters upon learning of his demotion, “but [I’ll] hang in there and figure it out.”

And while that decision wound up getting McAdoo fired, along with the general manager Jerry Reese, many now argue they made the right call, citing Manning’s halting ability to exploit the rookie running back Saquon Barkley and the veteran wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr. as proof. (The obvious subtext of this argument: Manning can’t throw it deep anymore.) Foremost among these second-guessers is Beckham, the three-time Pro Bowler who, in an ESPN interview on October 7 (with the rapper Lil Wayne at his side for some reason), insinuated that Manning was holding the team back. The Giants’ coach, Pat Shurmur, was quick to scuttle that theory and fine Beckham for his comments, but two weeks later, Shurmur was caught by ESPN cameras yelling “Throw it to Odell!” after Manning missed a clear chance to throw a touchdown to him in a game in which they were trailing by seven.

All that said, Beckham, and those aforementioned wisenheimers who say the Giants traded the wrong Eli, have it backwards. While it’s true that OBJ and Barkley rate among the league’s most explosive one-two punches, it’s also true that the Giants have played Manning behind some truly appalling offensive lines over the course of his 15 seasons. The team’s recent efforts to patch its protection holes—selecting the hulking Ereck Flowers ninth in the 2015 draft, signing Tom Brady protector Nate Solder to a four-year, $62 million contract in March—have thus far resulted in Manning getting sacked a league-high 31 times through eight games. Meanwhile, Barkley has rushed only for more than 100 yards in two games.

What’s more, the Giants haven’t done Manning any favors by not adding any backup quarterbacks who might actually light a fire under him. Instead, they’ve signed guys like Smith and David Carr—former starters who have buckled under pressure time and again. The leadership touted fourth-round rookie Kyle Lauletta and then, when he was arrested during the team’s bye week for nearly running over a police officer, moved on to hyping seventh-year journeyman Alex Tanney. If anyone’s holding the Giants back right now, it’s owners John Mara and Steve Tisch, for not trusting the process. (Likely, Manning doesn’t get benched and then reinstated without their say-so.) And it’s Gettleman, who had a ripe opportunity to find Manning’s replacement in this year’s draft but instead added Barkley, an incandescent talent who nonetheless plays a position with the league’s worst shelf life.

The Giants, despite Gettleman’s recent maneuvering, don’t figure to land a worthwhile Manning successor (or even a credible challenger) anytime soon. The 2019 draft already has pro quarterback evaluators “terrified.” In the past two years, they’ve seen seven of the best prospects for that draft leave school early. Many of those standouts who would have been in the class of 2019—like Mitchell Trubisky, Deshaun Watson, and Patrick Mahomes—have already gone on to become marquee NFL stars (in Chicago, Houston, and Kansas City, respectively). The three most intriguing prospects that remain—Oregon’s Justin Herbert, Missouri’s Drew Lock, and Auburn’s Jarrett Stidham—are still under-seasoned, scouts say. The best veteran quarterbacks all signed lavish free-agent deals last spring. And any attempt to move on from Manning before next season would cost the Giants at least $6.2 million in “dead” salary-cap commitments. Granted, that’s peanuts in the grand scheme of the team’s $164 million 2019 spending budget. But it’s enough to discourage the Giants from off-loading their most important player without a viable alternative.

New York might be stuck with Manning for at least another season, but is that such a bad thing? He has his coach’s support and a fresh vote of confidence from Mara. In other words, this is fine. For all of Manning’s obvious faults, no one can say he fell short of expectations. If anything, you can argue he had a better career than his more statistically prolific older brother (who could never quite solve the Patriots and was a loser in two Super Bowls), simply because he made more of his potential. Manning beat Tom Brady in the Super Bowl twice. And he’s brought home more Super Bowls than any other New York QB. Anything beyond that should be considered a bonus.

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz.—After the 2016 election, Anna French gave up on politics. The 28-year-old had been in the Javits Center in New York City on election night to hear Hillary Clinton give her victory speech. She was deeply involved in nonprofit circles focused on women’s rights and international development; she and her friends had spent the months leading up to the election trading updates about the landmark presidential race.

Then, Clinton lost. “At that point, I had kind of lost hope, like it was a lost cause,” French told me. “I always felt like my vote didn’t count, even though I voted. I always felt like politicians are all the same.”

So when her mom, Felicia, floated the idea of running for the Arizona statehouse in 2018, well: “I just didn’t think it was a good idea,” she said. Her mom is always “very optimistic and idealistic,” she said. “I guess I was afraid that politics would be the thing that finally ruined that about her.”

Despite her daughter’s objections, Felicia French decided to run. At first, Anna agreed to help her out for a few weeks, which turned into a few months. Then she was hooked. “The further we went on the campaign, the more energized I got,” Anna said. “The people we were meeting … saw my mom as this person who could really create positive change.” The more she saw other people getting excited about a state-level election, she said, “the more I realized: Well, maybe this is the way we change it.”

Elections on this level have a different feel than multimillion-dollar national races. Candidates are less polished. Many of the issues are more immediate. With margins of victory sometimes as close as a couple hundred votes, it’s easier to imagine that every ballot could determine the outcome of races.

But for all the inspiration that state- and local-level elections might offer, candidates also face extraordinary challenges—including having to argue that their races actually matter. National issues seem to have become the center of American politics, expanding to take over even the most parochial races.

This year, a slew of organizations, volunteers, and nominees have tried to refocus voters’ attention on what’s happening in their states and towns. To succeed, they’ll have to transform an entire political culture in which voters are obsessively focused on Washington, intensely tribalized, and essentially ignorant of how government can powerfully shape their lives, starting at the statehouse.

Former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill used to evangelize his view that “all politics is local,” but these days, it often seems like all politics is national. Local news coverage has collapsed and become increasingly centralized. President Donald Trump is at the center of every cable-news story. Research suggests that voters are less engaged and informed on local issues than national ones. And according to organizations working to influence state- and local-level races this year, faraway scandals have often been the central conversation when local candidates knock on voters’ doors.

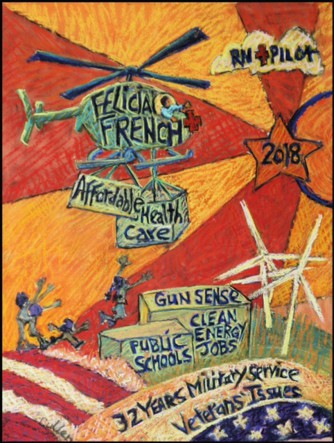

A local Sedona artist, Polly Cullen, reached out to French after being inspired by her campaign and offered to create a piece of art for her. (Courtesy of Polly Cullen)

A local Sedona artist, Polly Cullen, reached out to French after being inspired by her campaign and offered to create a piece of art for her. (Courtesy of Polly Cullen)In the rural areas of north-central Arizona, people often start political conversations with, “I’m a Republican, but …” according to French, who is running for the statehouse there as a Democrat. A lot of people are upset about state-level issues: Arizona’s low-ranked schools, for example, or the possibility that areas around the Grand Canyon will be opened up to uranium mining. But when French attends events, many people also share their perspectives on national issues that she would never be involved in as a state legislator: the way the U.S. Senate handled the nomination of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, for example, or the Trump administration’s decision to separate parents and children at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“It’s become worse and worse as the campaign goes on,” French said. “It does suck the oxygen, so to speak, out of the issues that we can [affect].”

[Read: Fighting for the right to vote in a tiny Texas county]

This year, national groups—especially on the left—have poured unprecedented resources into state and local elections. One of these organizations, Future Now Fund, has become a major funder in five states, including Arizona. “For years, narrow special interests have focused on states and it’s poisoned our entire democracy,” said Daniel Squadron, a former state senator in New York who runs the group. “We aren’t going to win the argument at cocktail parties in Washington, D.C. We’ll win it in state capitols like Phoenix by electing good people who are actually interested in improving lives.”

For Democrats in particular, this is a huge culture shift: Even before he left office, former President Barack Obama had started talking about Democrats’ fatal neglect of nonnational races—something for which he is partly blamed. According to the historian Julian Zelizer, Democrats lost upwards of 1,000 governorships and seats in state and federal legislatures during Obama’s time in office.

The premise of federalism is that government works best when it’s functioning at levels big and small; that politicians can be most effective and accountable when they are close to the people they represent. In practice, it can be difficult to see evidence of the connection between local politicians and their constituents—and easy to see why so many people seem to prefer national battles over state-level politics.

When French retired as an Army colonel in 2010 after 32 years as a nurse, a medevac helicopter pilot, and a senior medical adviser, she took on part-time gigs as a community-college instructor and a hospice nurse, and she volunteered for a regional search-and-rescue team. The 58-year-old has pepper-gray hair and an athletic build, and talks 10 times faster than she drives; she’s a rule follower, full of energy and newly found political fire.

In the past, French has been involved with environmental-advocacy efforts, and she has a special passion for endangered species like the Mexican gray wolf. But two summers ago, she decided to attend a boot camp hosted by a group called Emerge America, which trains women who are interested in becoming political candidates. The organizers were impressed by her résumé, and particularly her experience flying helicopters; for a while, she was the only woman in her flight-school class. Lead with that, French remembers them saying. “That’s badass.”

French long considered herself a Goldwater Republican: a career in the military, a fan of Ronald Reagan, proudly fiscally conservative. She switched her voter registration to independent around the time of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, during which she was deployed: She saw those wars as wasteful, she said, and by that point, “the Republican Party [had] left me,” particularly on climate and environmental issues. She only became a Democrat once she decided to run, because it made more sense to get the backing of a party.

Republicans hold all three state-legislature seats in Arizona’s sixth legislative district. In each district, voters can choose two candidates for the state House and one for the state Senate, and nominees from the same party will often run as a slate. The sixth is one of a handful of Arizona districts identified by Future Now Fund and other groups as potentially flippable in 2018. The district strongly leans Republican, but roughly one-third of voters aren’t registered with any party. That’s who French and her campaign have been trying to reach over more than a year of campaigning: the persuadable voters in the middle.

[Read: The midterms could permanently change North Carolina politics.]

From the beginning, French set the goal of reaching every part of her district, including tiny townships with barely 200 residents. When she’d visit rural areas, “people were shocked to see a candidate out there,” she said. Many people have no idea who their state representatives are, or even what their state legislators do; French has become an evangelist for voter registration. Especially in rural areas, she often asks conservative voters whether another candidate for statehouse has ever knocked on their door. No one has ever said yes, she told me.

As French has discovered, campaigning in a district like this is brutal. LD-6 stretches over a vast, Y-shaped area reaching from regions well below her rural hometown of Pine all the way up to the southern rim of the Grand Canyon. Traveling to different sections can take hours and hours of driving time. In the past, this has not been the “chosen district” for the state party, said one of French’s campaign managers, Sharon Edgar: The Democratic Party tends to pour its energy into the districts surrounding Phoenix, where a majority of its voters live. In the half-decade since the state’s districts were redrawn, the party has never been able to convince a Democrat to run here twice.

French has gotten some help from the state party: The Arizona Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, or ADLCC, sent several field organizers to her district. But she and the party have also disagreed. A party official advised French to refrain from listing her two master’s degrees and academic qualifications on her campaign materials, saying it would be “intimidating” or “not relatable” to the average person in the district. (French and her daughter said no.) The party also put a lot of pressure on French to do “call time,” which involves reaching out to potential donors and asking for money. After a few months of this, French flat-out refused to keep fund-raising this way, describing it as “demeaning.” She got by using money out of her military pension and attending house parties hosted by friends of friends of friends. According to state filing records, French has raised more than $135,000—more than four times as much as her opponent, the Republican incumbent, Bob Thorpe.

The past 14 months have been overwhelming, French said: “I haven’t had a day off since last year.” She has quit her two jobs, lost money on car mileage and meals, and faced her first attack ad. Normal life is impossible: She has no time for laundry or home repairs or grocery shopping. On her bad days, French often wonders to herself, “‘Why didn’t I just volunteer with Doctors Without Borders?’”

Still, despite everything, she would do it all again: She has pledged to run at least one more time, no matter what.

Felicia French and her daughter, Anna (Courtesy of Felicia French)