No dia 31 de agosto de 2018, jipes blindados alinharam-se ameaçadoramente ao longo de uma rua da Cidade de Guatemala. No meio da manhã, começaram a circular imagens dos veículos diante do escritório de uma comissão anticorrupção patrocinada pela ONU que havia ajudado a derrubar políticos corruptos. Jipes e soldados também foram vistos nos arredores do Palácio Nacional. Em um país com uma história relativamente recente de golpes militares e massacres, as fotografias e vídeos se espalharam como fogo em mato seco, gerando preocupação em uma população desorientada.

Para Feliciana Macario, essa demonstração de força lembra os piores anos do regime militar guatemalteco, durante os 36 anos de conflito armado entre forças militares e paramilitares apoiadas pelos EUA e guerrilhas de esquerda. Macario é uma das coordenadoras nacionais da Conavigua, uma organização de direitos humanos fundada por mulheres cujos maridos morreram ou desapareceram na guerra.

“É como se estivessem nos ameaçando com uma volta aos anos 1980”, diz Macario, uma mulher quiché (um dos grupos étnicos maias) que trabalha com vítimas e sobreviventes do período de repressão.

O conflito armado deixou mais de 200 mil mortos e 45 mil desaparecidos. Mais de 80% das vítimas eram civis indígenas, e o responsável, na esmagadora maioria dos casos, era o exército. Uma comissão da verdade patrocinada pela ONU e dois tribunais guatemaltecos classificaram os atos do exército no início dos anos 1980 como genocídio. O conflito terminou em 1996 com a assinatura dos Acordos de Paz, mas Macario diz que o atual presidente da Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, está violando os termos do tratado.

“Um dos compromissos que destacamos é o do papel do exército na sociedade. Nos termos do acordo, o exército devia reduzir seu efetivo, orçamento e tudo o mais. Mas Jimmy Morales está indo na direção contrária. Ele está aumentando o orçamento do exército e quer remilitarizar o país”, disse Macario ao Intercept.

Cerca de duas horas depois que os primeiros jipes foram avistados do lado de fora do escritório da Comissão Internacional Contra a Impunidade na Guatemala (CICIG), Morales apareceu no Palácio Nacional, rodeado de comandantes militares e policiais, e anunciou a não renovação do mandato da CICIG, o que provocou ações judiciais, protestos e uma crise política ainda em andamento. A mobilização dos jipes aumentou a preocupação de muitos guatemaltecos com Morales – ainda mais depois da revelação, por parte da embaixada dos EUA, de que os veículos haviam sido cedidos para serem usados nas fronteiras, e não na capital. Morales e seus apoiadores vêm tentando obter o apoio do governo Trump e do Partido Republicano contra a CICIG, e o tradicional apoio dos EUA à comissão parece estar enfraquecendo.

“Os veículos foram doados pelos EUA para combater o narcotráfico na fronteira, mas foram usados para intimidar a CICIG, violando completamente a letra do acordo”

Dois meses depois, as justificativas oficiais para a mobilização de veículos blindados do dia 31 de agosto continuam desencontradas: segundo o ministro do Interior, tratava-se de uma patrulha de rotina para combater a criminalidade; segundo documentos da polícia, o objetivo era proteger instituições e repartições públicas; para o presidente, os veículos estavam lá para evitar protestos violentos. A cada declaração ou documento oficial que vem a público, a história dos J8s fica ligeiramente – ou bastante – diferente.

Apesar das explicações cambiantes, uma coisa já está clara: o governo guatemalteco violou o acordo de doação de jipes J8 assinado com os EUA. Tanto o Departamento de Estado quanto o Departamento de Defesa americanos confirmaram ao Intercept que os veículos foram cedidos para operações específicas de combate ao narcotráfico nas fronteiras da Guatemala. Segundo ambos os órgãos, a transferência e emprego dos veículos fora desses parâmetros constituiriam uma violação do acordo de doação. E, segundo documentos da polícia guatemalteca obtidos pelo Intercept, foi exatamente isso que aconteceu no dia 31 de agosto – e nos meses anteriores.

“Os veículos foram doados pelos EUA para combater o narcotráfico na fronteira, mas foram usados para intimidar a CICIG, violando completamente a letra do acordo”, afirma Jordán Rodas, chefe da Procuradoria de Direitos Humanos da Guatemala, que acionou o Tribunal Constitucional do país contra a mobilização de 31 de agosto.

O presidente Jimmy Morales anuncia a não renovação do mandato da comissão anticorrupção da ONU em uma coletiva de imprensa na Cidade da Guatemala, no dia 31 de agosto de 2018.

Foto: Orlando Estrada/AFP/Getty Images

O antagonismo entre Morales e a CICIG vem crescendo há mais de um ano. A comissão atua em conjunto com o Ministério Público há mais de uma década, mas foi nos últimos anos, durante a chefia de Iván Velásquez, um ex-procurador e juiz colombiano, que essa parceria acumulou êxitos em casos de grande notoriedade. Graças às investigações, dezenas de políticos, advogados e executivos do setor privado foram presos por corrupção, incluindo um ex-presidente.

Morales, um ex-comediante de TV apoiado por militares linha-dura de direita, foi eleito presidente no fim de 2015, aproveitando-se de uma onda de fervor anticorrupção e prometendo apoiar o trabalho da CICIG. Um ano e meio depois, contudo, a promessa foi esquecida quando Morales, dois de seus parentes e seu partido viraram alvo de investigações criminais. Em agosto de 2017, Morales tentou expulsar Velásquez do país, mas foi impedido pelo Tribunal Constitucional.

Desta vez, Morales agiu para impedir que Velásquez voltasse ao país, mas o decreto também foi declarado inconstitucional. O presidente e vários membros do governo reclamam de ordens ilegais e manipulação internacional, e dizem que não vão permitir a volta de Velásquez. O Ministério da Defesa e o exército anunciaram que vão respeitar a decisão da Justiça, mas Morales e seus aliados mais próximos continuam desafiando o Tribunal Constitucional. Com o apoio da ONU, Velásquez continua chefiando a CICIG do exterior.

“Jimmy Morales está aumentando o orçamento do exército e quer remilitarizar o país”

Com o aumento da instabilidade e dos protestos, o governo mudou sua versão sobre o envio de carros blindados para o escritório da CICIG no mesmo dia do anúncio do fim do mandato da comissão. Em uma coletiva de imprensa, o ministro do Interior, Enrique Degenhart, a ministra das Relações Exteriores, Sandra Jovel, e outros membros do gabinete de Morales afirmaram que os J8s estavam em uma patrulha de rotina, parte de uma operação de combate ao crime. Um relatório do Ministério do Interior redigido depois do incidente, ao que o Intercept teve acesso, descreve planos de operações que vão de um mês antes até um mês depois do 31 de agosto. No entanto, a operação dos dias 30 e 31 de agosto, segundo o documento, foi diferente das outras. A missão do destacamento teria sido monitorar e proteger instituições e repartições públicas. Membros do governo usaram essa versão dos acontecimentos em declarações posteriores.

Porém, no dia 3 de outubro, em uma entrevista no rádio, Morales contradisse publicamente seus ministros – e relatórios de seu próprio gabinete obtidos pelo Intercept – e declarou que os jipes haviam sido mobilizados para evitar protestos violentos.

Oscar Pérez, porta-voz do Ministério da Defesa, encaminhou o Intercept ao Ministério do Interior para quaisquer perguntas sobre os J8s, recusando-se a comentar a contradição entre as diferentes versões oficiais do ocorrido. Mesmo após a insistência da reportagem, Pérez não quis dizer se havia soldados ou funcionários do exército presentes nas operações do dia 31 agosto. Segundo ele, os jipes e a força-tarefa estariam sob comando civil. O Ministério do Interior e Morales não responderam às inúmeras tentativas de contato da reportagem.

Por e-mail, um porta-voz do Departamento de Estado americano afirmou que o órgão monitora atentamente o uso dos veículos cedidos pelos EUA, acrescentando que a embaixada manifestou sua preocupação em um comunicado público quando os jipes foram vistos pela primeira vez. “O governo dos EUA leva muito a sério toda acusação de uso indevido de material bélico americano, e vai tomar as devidas providências após o término das investigações”, disse o porta-voz.

Segundo outro porta-voz do Departamento de Estado, o acordo determina que os J8s devem ser usados na luta contra o narcotráfico. Além disso, ainda segundo o porta-voz, as operações de combate a atividades criminais, principalmente ao tráfico de drogas, devem ser realizadas nas fronteiras da Guatemala. Já o Departamento de Defesa ressaltou a mesma questão, só que de maneira mais detalhada.

“Os jipes J8 foram cedidos entre 2013 e 2018 para dar apoio às operações de três Forças-Tarefas Interinstitucionais [IATFs, na sigla em inglês] guatemaltecas – Tecún Umán, Chorti e Xinca –, compostas por unidades policiais, militares e aduaneiras e lideradas por um chefe de polícia sob a tutela do Ministério [do Interior]”, disse ao Intercept Johnny Michael, porta-voz do Departamento de Defesa, em um e-mail de resposta a uma série de perguntas.

“Os contratos de cessão desses veículos determinam que as IATFs se concentrem no combate a atividades criminais, principalmente ao tráfico de drogas, nas fronteiras da Guatemala. O emprego dos J8s deve priorizar a segurança das fronteiras e áreas com alto índice de criminalidade. Os documentos determinam que os J8s devem ser usados em operações antidrogas”, escreveu Michael.

Segundo ele, o governo da Guatemala não notificou os americanos de nenhuma transferência ou alteração na missão dos veículos cedidos, mas o Departamento de Defesa dos EUA estaria investigando “comentários que apontam para uma aparente transferência e ampliação dos usos do J8” e consultando o Departamento de Estado sobre futuras providências a tomar.

Não há dúvidas de que essas transferências aconteceram. O Intercept teve acesso a mais de 100 páginas de documentos e relatórios da polícia e do Ministério do Interior da Guatemala entregues ao Tribunal Constitucional, que havia exigido uma explicação para a presença dos veículos em frente ao escritório da CICIG no dia 31 de agosto. Segundo relatórios policiais, os jipes foram deslocados para a Cidade de Guatemala no início de abril de 2018 “com o objetivo de reduzir a criminalidade”.

“Cada país tem três chances antes de sofrer alguma sanção? As ajudas futuras são interrompidas? Não sabemos”

A transferência de quatro J8s das forças-tarefas Chorti e Xinca foi requisitada no dia 23 de abril para uma operação de segurança de dois dias na Cidade de Guatemala. A polícia continuou transferindo mais veículos das forças-tarefas para diversas operações na capital nos quatro meses anteriores ao 31 de agosto.

Essas transferências demonstram que o emprego dos jipes pela Guatemala desrespeitou todos os três itens ressaltados pelo Departamento de Estado e pelo Departamento de Defesa dos EUA: finalidade (combater o narcotráfico), geografia (regiões fronteiriças) e comando (forças-tarefas interinstitucionais).

O acesso a dados sobre o monitoramento das doações de equipamento militar americano a forças de segurança estrangeiras pode ser difícil, segundo Adam Isacson, diretor do programa Defense Oversight, do Washington Office on Latin America. Entre 1990 e 2005, o governo dos EUA impôs restrições às ajudas militares à Guatemala devido ao histórico de violações de direitos humanos no país.

Desde então, segundo Isacson, a maior parte da ajuda recebida pelos guatemaltecos – onde estão incluídas as forças-tarefas interinstitucionais – tem vindo do Pentágono. “Mais especificamente, de um programa do Departamento de Defesa. Antes chamado de ‘Seção 1.004’, ele foi rebatizado de ‘Programa de Combate às Drogas e ao Crime Organizado Transnacional’. Como o nome indica, as ajudas só podem ser usadas para isso”, diz.

Para Isacson, o Departamento de Defesa é menos exigente em termos de prestação de contas do que o governo federal. O único relatório apresentado ao Congresso é uma planilha contendo apenas o nome do país e a categoria, sem entrar em detalhes sobre o conteúdo da ajuda.

“Não temos acesso ao acompanhamento desses acordos. Nunca temos. Essas informações são confidenciais, como de costume”, afirma Isacson. Como resultado, as consequências das violações de contrato são desconhecidas. “Cada país tem três chances antes de sofrer alguma sanção? As ajudas futuras são interrompidas? Não sabemos”, lamenta.

Manifestantes protestam contra a decisão do presidente da Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, de não renovar o mandato de uma comissão anticorrupção patrocinada pela ONU. Cidade da Guatemala, 14 de setembro de 2018.

Foto: Luis Echeverría/Reuters

Na tarde do dia 31 de agosto, Rodrigo Batres, pesquisador do grupo de análise política El Observador, compareceu a uma manifestação improvisada na praça principal da capital poucas horas depois do anúncio de Morales.

Não era a primeira vez que a população protestava contra as tentativas do governo de sabotar a comissão anticorrupção, e algumas pessoas já tinham até preparado cartazes de apoio à CICIG. Outras agitavam bandeiras da Guatemala. Foi nesse momento que a embaixada americana emitiu o comunicado sobre os jipes doados. Mais cedo, a representação diplomática dos EUA já havia reagido à notícia de que o mandato da CICIG não seria renovado.

Os EUA estavam “cientes” da decisão, afirmava o comunicado inicial, acrescentando que o governo americano acreditava que a CICIG era “uma parceira importante e eficaz na luta contra a impunidade, melhorando a governança e fazendo com que os corruptos respondam por seus crimes na Guatemala”. Para depois afirmar que os EUA “continuarão a apoiar a luta da Guatemala contra a corrupção e a impunidade”, considerada “parte indissociável” das relações bilaterais entre os dois países. Para muitos guatemaltecos, ao não condenarem inequivocamente a decisão de Morales e continuarem a apoiar a luta do governo contra a corrupção – mas sem a CICIG –, os EUA estavam defendendo o presidente.

“Aquele comunicado foi muito importante. Os EUA disseram que iriam respeitar a decisão do governo e que continuariam a apoiar o combate à corrupção. Acho que foi uma forte declaração de apoio a Morales, e essa mudança foi concomitante à mudança de governo aqui nos EUA”, disse Batres ao Intercept.

Os EUA são o maior financiador da CICIG, tendo contribuído com 44,5 milhões de dólares de 2007 a 2017 – mais de um quarto do orçamento total da comissão. No passado, os EUA faziam coro com os outros grandes doadores – Canadá e União Europeia –, na defesa da CICIG. Mas desta vez o país ficou de fora da declaração conjunta dos financiadores, que lamentava a decisão da Guatemala de proibir a entrada de Velásquez no país. Alguns observadores suspeitam que a mudança de tom seja consequência do intenso lobby de Morales e seus apoiadores, que apresentam o presidente como um aliado fundamental dos EUA na região.

A Guatemala foi um dos únicos países que apoiaram a decisão de Donald Trump de reconhecer Jerusalém como a capital de Israel. Dias depois da transferência da embaixada americana para a cidade, a Guatemala fez o mesmo. Morales também foi o último líder centro-americano a condenar a política do governo Trump de separação familiar na fronteira. A direita guatemalteca alega que a CICIG é um terreno fértil para agentes estrangeiros radicais, e essa visão tem ganhado força no Congresso dos EUA. O senador republicano Marco Rubio bloqueou 6 milhões de dólares destinados à CICIG em maio (os fundos já foram liberados).

Em sintonia com o primeiro comunicado da embaixada americana, membros do governo Trump têm reiterado seu apoio a Morales. O secretário de Estado, Mike Pompeo, tuitou no dia 1º setembro: “Temos muita admiração pelos esforços da Guatemala na segurança e na luta contra as drogas” – sem nenhuma menção à CICIG. Cinco dias depois, Pompeo ligou para Morales para manifestar o apoio dos EUA à soberania da Guatemala e “o contínuo apoio dos EUA a uma CICIG reformada”. Pompeo prometeu trabalhar com a Guatemala na implementação de uma reestruturação da comissão no que vem, segundo o Departamento de Estado. Mas os detalhes dessa reforma não foram revelados.

Batres acha que os EUA vão continuar apoiando Morales enquanto defendem, da boca para fora, o combate à corrupção e à impunidade. “Embora defendam as instituições, eles não vão deixar de respaldar um dos governos mais submissos da região”, disse ele, levantando a voz em meio aos gritos dos manifestantes.

Tradução: Bernardo Tonasse

The post Cedidos pelos EUA para combater o tráfico de drogas, veículos militares foram usados para intimidar comissão anticorrupção na Guatemala appeared first on The Intercept.

Republican leaders in the House of Representatives undercut a bipartisan effort to end U.S. involvement in Yemen by sneaking a measure that would kill an anti-war resolution into a vote about wolves.

On Tuesday night, the Republican-led House Rules Committee voted to advance the “Manage Our Wolves Act,” which will remove gray wolves from the endangered species list. The Rules Committee waived all points of order against the bill and voted to advance it to the floor.

The catch: Republicans inserted language that would block a floor vote on whether to direct President Donald Trump to end U.S. involvement in the Saudi- and UAE-led intervention in Yemen. The intervention has been highly destructive, flattening homes, roads, markets, hospitals, and schools, and leading to the world’s largest humanitarian crisis.

On Wednesday evening, the House approved the rule 201-187, largely on party lines, successfully blocking a vote on the Yemen resolution.

In September, Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., introduced the Yemen resolution, which would have directed the Trump administration to remove U.S. forces from “hostilities” related to the Saudi-led intervention. Because it invoked the 1973 War Powers Act, Khanna’s resolution was “privileged” under House Rules, meaning it could bypass a committee vote and, barring any interference from the powerful Rules Committee, get a vote on the floor. The Republican gambit caused Khanna’s resolution to be stripped of its “privileged” status, meaning that it did not come up for a vote on its own.

If the Yemen measure had come up for a vote, it would have been the first time a chamber of Congress, which is notorious for avoiding votes on issues of war and peace, took an up-or-down vote that could end U.S. involvement in the conflict in Yemen.

On Capitol Hill, outrage against Saudi Arabia is at an all-time high following the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi at the hands of Saudi agents last month. The measure had 81 co-sponsors, including four Republican members and several top Democrats. Two Democratic aides told The Intercept that Khanna’s measure needed about 30 Republican votes to pass, and they were optimistic about getting them.

“Republican leadership had to kill the bill in a surprise, underhanded maneuver,” Eric Eikenberry, advocacy officer at the Yemen Peace Project, told The Intercept in an email. “If they didn’t, they risked further rank-and-file Republican cosponsors and a floor vote, a prospect which leadership, always bent on ensuring impunity for the administration, could not abide.”

After a strong showing in last week’s midterm elections, Democrats can revive Khanna’s resolution after January, when the House switches to Democratic control. The top Democrat on the Rules committee, Jim McGovern, D-Mass., is a co-sponsor.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates began their intervention in Yemen in March 2015, aiming to retake the capital from a rebel group called the Houthis. The Trump and Obama administrations have stood by the coalition, providing weapons, intelligence, and midair refueling of coalition aircraft. The Washington Post reported on Friday that the Trump administration would cease midair refueling amid a growing outcry, but that did not satisfy many of the war’s critics on Capitol Hill.

Update: November 14, 2018, 6:07 p.m. EST

This story has been updated to include the results of the House vote on the rule removing gray wolves from the endangered species list and blocking a resolution to withdraw U.S. support for the Saudi-led bombing campaign in Yemen.

The post Republicans Used a Bill About Wolves to Avoid a Vote on Yemen War appeared first on The Intercept.

Cuba anunciou hoje que vai encerrar o contrato que tem com o Brasil no programa Mais Médicos. Declarou o governo da ilha em nota oficial: “O presidente eleito do Brasil, Jair Bolsonaro, com referências diretas, depreciativas e ameaçadoras à presença de nossos médicos, disse e reiterou que modificará os termos e condições do Programa Mais Médicos, desrespeitando a Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde e o que esta acordou com Cuba, ao questionar o preparo de nossos médicos e condicionar sua permanência no programa à revalidação do título e como única forma de se contratá-los a forma individual.”

A saída dos médicos cubanos do Brasil é uma porrada política forte no novo governo que ainda não começou. Talvez a mais forte delas até agora porque, dessa vez, por mais que tente, Bolsonaro não controla a narrativa.

O problema objetivo: os médicos cubanos atuam, sozinhos, em 1575 cidades (lembrem que o Brasil tem 5.570 municípios). Esses médicos cubanos cuidam de 24 milhões de pessoas. Ainda não há data para que os profissionais parem de atuar no Brasil mas, de uma hora pra outra, muita gente pode ficar sem médico. É uma crise gigantesca sem solução fácil. As bravatas de Bolsonaro, dessa vez, não servirão para nada além de agradar ao fandom. Isso abre as portas para que milhões de pessoas comecem o ano irritadas com o novo governo.

Leiam o que escreveu a repórter Nayara Felizardo em uma reportagem sobre a cidade de Guaribas, no interior do Piauí, publicada no mês passado:

“Outro programa que os moradores temem que termine é o Mais Médicos. Os médicos cubanos, contam, estão disponíveis todos os dias e ainda visitam as famílias em casa, se for preciso. Antes, não havia nenhum médico residente na cidade, e o atendimento acontecia uma vez a cada um ou dois meses.”

Guaribas não é exceção. Muitas cidades não tinham médicos antes do começo do programa, em 2013.

Do ponto de vista da retórica de Bolsonaro, as opções postas na mesa até agora são péssimas:

1. Ele pode voltar atrás de suas declarações (pra variar) estapafúrdias e sem pé na vida real e negociar com Cuba pra manter os 8.612 médicos por aqui – e se tornar automaticamente aquilo que critica, um “financiador de uma ditadura comunista®”, o que deve pôr boa parte de seus eleitores em tilt ideológico.

2. Ele pode ver os cubanos indo embora e começar a lidar nos primeiros meses de governo com a insatisfação de milhões de pessoas em todo o país.

Bolsonaro fala demais. Verba volant, mas às vezes é um bumerangue que volta direto na sua cara.

Bom feriado.

The post O desembarque de Cuba do ‘Mais Médicos’ embretou Bolsonaro entre o comunismo e a desaprovação popular appeared first on The Intercept.

Chicago detective Dante Servin shot Rekia Boyd in the back of the head late on a warm night in March 2012. Servin was an off-duty detective, a 20-year Chicago police veteran who lived on the block of the shooting, just off Douglas Park on the city’s West Side. Boyd was a 22-year-old African-American woman hanging out in the park with some friends. She was unarmed.

As police converged on the scene, Servin told his fellow officers that he had asked Boyd and her friends to quiet down as he drove out of the alley next to his house. According to Servin, a man in the group, Antonio Cross, responded by pointing a gun at him. Servin then fired five shots over his shoulder from inside his car. One hit Cross’s hand. Another hit Boyd, who fell to the ground.

Ambulances rushed both victims to the hospital while detectives prepared charges against Cross. Officers, including a canine team, spread out to look for the gun Servin claimed he had seen. Meanwhile, Servin freely wandered the scene, talking with a succession of detectives and police supervisors.

Soon, a deputy chief named Eddie Johnson took command of the crowd of officers outside Servin’s house. As the designated on-call incident commander, Johnson assumed responsibility for the department’s initial investigation of the shooting. The OCIC is a central part of the department’s response to police shootings, operating at the scene “with the authority of the superintendent of police,” according to Chicago Police Department regulations.

Johnson faced a difficult task. The first hours after the shooting were marked by conflicting accounts from Servin and multiple civilian witnesses. The undisputed facts of the case were also disturbing: An off-duty officer had shot an unarmed woman in the head. And he had fired into a group of civilians, typically a violation of department rules.

Yet Johnson and the officers under his direct command proceeded to make a number of troubling decisions. In the days after the shooting, witnesses told investigators that Servin appeared to have been drinking. When asked several months after the shooting if he had been drinking that night, Servin told a film crew, “That’s my damn business.” Police investigators waited six hours to administer a blood alcohol test.

Detectives also discovered cameras mounted on Servin’s house that looked directly over the scene of the shooting. When Servin said the cameras didn’t work, instead of insisting on inspecting them or obtaining a search warrant, detectives dropped the matter, eventually asking him to sign an affidavit swearing that the cameras were inoperable.

Detectives also quickly uncovered evidence that Cross had been unarmed. Civilian witnesses denied that Cross had a weapon, and although there was a trail of blood and dashcam footage clearly showing Cross’s path after the shooting, police were unable to find a gun. Despite these findings, police asked prosecutors to charge Cross with felony assault and issued a press release falsely claiming that Servin had fired only after Cross began to “approach him with a handgun” and “pointed the weapon in the direction of the detective.”

At 10:40 a.m., about nine hours after the shooting, Johnson concluded his initial investigation into Servin’s use of force and endorsed the detective’s account in his official use of force report. “Based on the facts available at this time, Officer Servin acted in compliance with department policy,” he wrote, approving Servin’s decision to open fire. “Officer Servin fired his weapon at the offender after the offender pointed a firearm at Officer Servin.” Johnson did not check the box in his report that would have recommended the case for further investigation. The official use of force report Johnson signed never mentioned Rekia Boyd.

Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

Boyd died the next day. In the weeks that followed, the official police narrative unraveled. Search teams never found Cross’s alleged gun at the scene. Cross also continued to insist that he had been holding only his cellphone. Five people eventually testified that he was unarmed that night. Police dashcam video also shows that Cross flagged down a police car within moments of the shooting. “I wanted police to catch the person who shot me,” he later testified. Within a week, 200 protesters rallied in Douglas Park, and Boyd’s case helped fuel a national movement to end police violence against black women. Eventually, prosecutors dropped charges against Cross, and the city paid Boyd’s family a $4.5 million settlement. Servin was eventually indicted for involuntary manslaughter, but charges were abruptly dismissed after a judge ruled that prosecutors should have charged him with murder.

On November 23, 2015 — three and a half years after the shooting — Superintendent Garry McCarthy initiated the process of firing Servin. Less than 24 hours later, faced with a court order, his department also released video footage of the police killing of Laquan McDonald.

That grainy dashcam footage of Officer Jason Van Dyke firing 16 shots into a teenager upended Chicago, sending thousands of protesters into the streets. Mayor Rahm Emanuel fired McCarthy and delivered an emotional speech, in which he apologized for McDonald’s death and acknowledged the existence of a police “code of silence” — a stunning admission in a city where the political establishment has long paid deference to the police. Emanuel promised that the CPD’s next leader would be a transformational figure, declaring that he was “looking for a new leader for the Chicago Police Department to address the problems at the very heart of the policing profession.”

Four months later, Emanuel announced his choice: Eddie Johnson, the 27-year police veteran who had approved Rekia Boyd’s shooting as a justified use of force.

Photo: Chicago Police Department via AP

In early 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a comprehensive report on the Chicago Police Department, concluding an investigation opened in the aftermath of the Laquan McDonald video release. Finding a “pattern of unlawful force” by officers, the DOJ declared that “the failure to review and investigate officer use of force has helped create a culture in which officers expect to use force and not be questioned about the need for or propriety of that use.”

Craig Futterman, a civil rights attorney and law professor at the University of Chicago Law School who helped lead a lawsuit that sought to force the CPD to undergo court-monitored reform, said that Johnson’s actions on the night of Rekia Boyd’s shooting could be described as “investigation as cover-up.”

“My assessment is that he did indeed in this case endorse a false report in affirmatively writing and documenting, despite the absence of evidence of a gun, that this is a justified shooting because the person had been pointing a gun,” Futterman said.

At least one CPD official has been punished for making a similar decision: Chicago’s inspector general recommended that Deputy Chief David McNaughton be fired in part for signing off on a false use of force form in the killing of Laquan McDonald. McNaughton quietly retired soon after.

In an interview with CBS Chicago shortly after his selection as superintendent, Johnson insisted that he could direct Chicago’s police reforms, declaring, “I’ve actually never encountered police misconduct, ’cause you got to understand, officers that commit misconduct don’t do it in front of people that they think are going to hold them accountable for it.”

The statement was widely mocked, with one columnist questioning whether the superintendent had “come down with a case of temporary misconduct blindness.” But few publicly considered another explanation for the baffling statement — that Johnson was telling the truth and saw shootings like Boyd’s not as misconduct, but as acceptable police procedure.

In fact, the Rekia Boyd case was not an aberration. An investigation of Johnson’s record, drawing on documents obtained by the Invisible Institute via litigation and included in the Citizens Police Data Project, shows that he repeatedly approved police shootings or ignored allegations of excessive force over his years as a supervisor, consistently finding that they did not qualify as misconduct.

Dante Servin’s use of force report from the night of Rekia Boyd’s shooting. Servin did not mention Boyd in his report. Eddie Johnson approved Servin’s decision to use force about nine hours after the shooting.

In a decade as a senior CPD supervisor, Johnson personally investigated or commanded the officers responsible for six controversial shootings that left five people dead — all young African-Americans — and cost Chicago more than $13 million in misconduct payments. Moreover, Johnson’s tenure as commander of Chicago’s 6th Police District from 2008 to 2011 was marred by serious allegations of misconduct by an elite tactical squad led by a scandal-plagued lieutenant named Glenn Evans. During six months in 2010, members of the roughly 45-person team participated in the fatal shootings of three men, all unarmed or fleeing. During the same period, the entire rest of the CPD killed four people. Another of Johnson’s officers was credibly accused of killing a teenager and planting a gun on his body. After his promotion to deputy chief in 2011, Johnson reviewed and approved more disputed shootings, including the killing of Boyd and a case in which an officer fatally shot a teenager in the back. Johnson was recently called to testify in that final case, but otherwise neither Johnson nor Emanuel has ever acknowledged the superintendent’s involvement in some of the department’s most notorious recent police shootings.

Johnson’s history in the department raises troubling questions about the future of police reform in Chicago. Although Emanuel has announced that he won’t be seeking re-election, he will nonetheless wield considerable power over Chicago’s new police oversight agreement during his remaining half-year in office. Emanuel also appointed Johnson with the unanimous approval of Chicago’s City Council, circumventing the official process and ignoring two outside reformers carefully vetted by Chicago’s Police Board. No politician or newspaper raised the issue of Johnson’s involvement in some of the department’s most notorious scandals. Can a man whose career embodies the CPD’s failure to rigorously review and investigate officers’ use of force — the unlawful pattern the recent Department of Justice report placed at the center of the reform agenda — transform the department?

Photo: Jose M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune/TNS via Getty Images

Johnson first took charge of Chicago’s 6th District in March 2008. The predominately African-American district stretches from blocks along West 79th Street that rank among the city’s poorest to the tidy, middle-class bungalows of Chatham that have been home to generations of the city’s black political, business, and civic leaders.

Johnson had risen quickly through the ranks of the CPD. Just a year earlier, he had been a sergeant, a position that typically directs up to a few dozen officers. As a district commander, he was now responsible for approximately 350 police officers serving 105,000 residents.

As the CPD — like departments nationwide — places increasing emphasis on data-driven policing, its commanders face relentless pressure to produce good numbers: high arrest figures and declining reports of crimes. Upon assuming his new post, Johnson made changes, picking a new leader for his tactical team. Such teams — usually composed of roving plainclothes officers — handle more aggressive police work, serving warrants and targeting high-crime corners. The size of the tactical team varied slightly over time, but typically there were between 40 and 45 officers. Assignment to a tactical team is often a step up for patrol officers, but it also brings extra risks. Johnson chose a hard-charging lieutenant named Glenn Evans to lead his tactical team.

“These kinds of units are almost by definition likely to be involved in more use of force incidents,” said Sam Walker, a policing expert from the University of Nebraska who consults with police departments, including the CPD. “Departments have to take special precautions in terms of clear policies, much closer supervision, than would be the case with just regular patrol units.”

Many officers and residents respected Evans’s dedication to police work — he was known to sleep in his office and patrolled the streets alongside his officers — but he also racked up dozens of complaints and several lawsuits as he rose through the ranks. A formal investigation into a 2005 complaint by Evans’s ex-girlfriend found that he called her a “whore” and damaged her car. The city also paid a nearly $100,000 settlement after a partially paralyzed city worker accused Evans of beating him up. Those cases were not outliers. A report on 1,500 CPD officers compiled by a former epidemiologist and obtained by WBEZ showed that Evans garnered more excessive force complaints than any other officer between 1988 and 2008.

In a sworn deposition taken in 2015, Evans displayed a cavalier attitude toward CPD procedures, declaring that “department orders are a guideline and nothing more.”

Johnson knew Evans long before he moved him to the tactical team. Early in their careers, the two served together as patrolmen in the 6th District. Both were also among the small number of black officers in the CPD’s upper ranks. Johnson explained his support for Evans in a 2017 deposition: “He had a reputation as being a good aggressive officer.”

Evans’s approach to policing soon triggered a backlash, and allegations of excessive force began to swirl around his tactical team as a cadre of younger officers with lengthy complaint records joined the squad. Among the new additions was Jason Landrum, who had shot three people in five years, including a man he shot in the stomach after his partner handcuffed him to a fence.

The new officers appear to have had a major impact on the squad. By mid-2011, toward the end of Johnson’s tenure as commander, officers serving on his tactical team had received an average of seven complaints each over the previous three years, a 70 percent increase from when he took over the district and four times that of the average CPD officer.

Graphic: Moiz Syed/The Intercept

A string of lawsuits accompanied the complaints. The city paid a settlement of nearly $500,000 after allegations that a 6th District officer shoved a man down a flight of stairs — fracturing his leg — and a tactical officer shot his dog. A nearly $41,000 settlement followed allegations that tactical officers handcuffed a man with a heart condition and then tased him twice, and a $60,000 settlement came after a man alleged that tactical officers illegally searched him and then harassed him after he filed a complaint. A woman named Rita King alleged that Evans fractured her nose inside the 6th District headquarters, repeatedly telling her, “I’m going to push your nose through your brain.” The city of Chicago paid King $100,000 to settle her case.

Beyond the lawsuits, Johnson reviewed many of the formal complaints in his capacity as commander. In one case, a woman accused Evans of unjustly shooting her dog. Investigators cleared Evans despite acknowledging that all five non-police witnesses had provided accounts that “drastically contradict” Evans’s explanation of the shooting. Johnson affirmed that the shooting was justified.

The growing stream of brutality complaints and lawsuits against the tactical team reached its peak in 2010, when tactical officers were involved in three fatal shootings — all of which killed young men who were unarmed or fleeing — in just six months.

The first took place in July, when two tactical officers approached a young black motorist named William Hope Jr., who was parked outside of a Popeyes around lunchtime. According to the officers, Hope responded by trying to run over one of the officers with his car. The officer’s partner then fired four shots, fatally wounding the 24-year-old.

A lawsuit brought by Hope’s family presented a starkly different account. On the witness stand, one of the officers admitted that Hope’s car had been moving at three miles per hour, matching eyewitnesses who claimed that Hope presented no danger to the officers. Ultimately, the jury ruled that the shooting was unjustified and awarded Hope’s family over $4.5 million. The verdict also ordered the officers to present the case to police recruits as an example of bad policing.

Less than two months later, officers took off in pursuit of a motorist named Garfield King. King had fled a routine traffic stop, worried that officers would find his illegal gun. The multi-car pursuit ended in a collision between King’s vehicle and a police car. King’s car caught fire, and two officers suffered fractured bones. Seven officers, including three tactical officers and two 6th District patrolmen, then opened fire, killing King and wounding his girlfriend, one of three unarmed passengers who had been trying to convince King to surrender. She later told investigators that King never tried to use the gun. The officers who chased King and fired 30 shots into his car knew only that he had fled a traffic stop.

A photograph of Garfield King’s car. After a high-speed chase, his car collided with an unmarked police vehicle. Officers claimed that he then tried to hit officers with his car. Seven officers fired 30 shots at King, killing him and wounding his unarmed girlfriend who had been trying to convince King to surrender.

Photo: Chicago Police Department

Chicago’s Independent Police Review Authority, or IPRA, ruled the shooting justified, but the department’s policy at the time stated that “when confronted with an oncoming vehicle and that vehicle is the only force used against them, sworn members will move out of the vehicle’s path.” The Department of Justice later raised concerns about shootings of motorists as well, pointing out that “shooting at a moving vehicle is inherently dangerous and almost always counterproductive.”

Troubling details also emerged about the third tactical team shooting, when tactical officer Tracey Williams shot and killed Ontario Billups in December 2010. Williams claimed that Billups menaced her with a dark object, possibly a handgun. Investigators eventually confirmed that Billups was unarmed. The dark object Williams saw was likely a plastic bag of marijuana. The city paid Billups’s family $500,000 to avoid a trial.

Reached by phone, Glenn Evans said that both his lawyer and the CPD superintendent’s office, “told me not to speak, but I will until they give me a direct order not to.” Evans proceeded to defend his officers, highlighting a 2010 case in which a suspect opened fire on tactical officers, including Evans. Officers resolved the situation peacefully. “We were able to talk it out. … We didn’t beat anyone up, we didn’t torture anyone, we didn’t abuse anyone.”

Evans said that the officers involved in the three fatal shootings in 2010 were “exceptional officers, exceptionally decorated … extremely good officers.” When asked about the names of the three men killed by his officers — Ontario Billups, William Hope Jr., and Garfield King — Evans said, “I don’t even know who these guys are.”

Chicago Police officers serving on the 6th District Tactical Team in May 2011. Graphic: Invisible Institute

The killings of Billups, Hope, and King within a six-month period by members of a single squad of 45 officers was highly unusual. During the second half of 2010, the other members of the CPD — nearly 13,000 officers — killed just four people. “If [a tactical squad] has more of these incidents compared with other tactical squads, there’s an obvious issue there related to supervision,” said Walker, the policing expert.

Commanders are generally “very aware” of misconduct investigations involving their officers and have wide authority over their tactical teams, said Robert Lombardo, a 30-year CPD veteran who later served as deputy chief of the Cook County Sheriff’s Police Department and is now a criminal justice professor at Loyola University Chicago. “If they have a personal concern, as they’re called, you put them back in uniform. You take them off the TACT team,” he said. “They have no right to the TACT team, it’s not in the contract. You serve at the pleasure of the commander, so if he doesn’t like the way you’re working, you go back in uniform and he puts someone else there.”

Following the fatal shootings, none of the officers were moved off the squad or off the street. Nor was Evans, their supervisor, reassigned, choices that had serious consequences. Over the next five years, the seven 6th District officers who fired shots in the three fatal shootings would open fire another eight times — nearly 30 times the CPD average. Those subsequent shootings, many in the 6th District, wounded four people and left 19-year-old Niko Husband dead.

The officer who shot Husband was Marco Proano, a non-tactical officer who had also fired shots in the killing of Garfield King. Proano was one of a number of regular patrol officers accused of serious misconduct while serving under Eddie Johnson.

Proano killed Husband outside a South Side dance hall in July 2011. Officers claimed that the teenager was holding a young woman hostage and brandishing a gun. The same woman testified in court that she was a childhood friend of Husband’s and that the two had been hugging when the officers approached. She also denied that her friend had a gun. A jury awarded Husband’s family $3.5 million after a trial in which the family’s lawyer alleged that Proano and two other officers had planted a gun on Husband’s body after killing him. Under Johnson, Proano was not punished. The CPD instead awarded him a medal for valor for the shooting.

Former Chicago police Officer Marco Proano leaves the federal building in Chicago on Aug. 28, 2017.

Photo: Terrence Antonio James/Chicago Tribune via AP

In November 2017, a federal jury convicted Proano on charges of using excessive force for firing multiple shots into a car full of unarmed black teenagers, injuring two, while on patrol in the 6th District in 2013, after Johnson had left his role as commander. Charges against Proano came after a retiring judge in a criminal case involving one of the teenagers leaked video of him shooting into the car to the Chicago Reporter, calling Proano’s actions one of the worst things he’d seen in over 30 years as a judge and public defender. He told the Reporter that “I’ve seen lots of gruesome, grisly crimes, but this is disturbing on a whole different level.”

Proano’s shooting of Husband was one of four controversial shootings by non-tactical officers working in the 6th District under Johnson. These cases included two other fatal shootings in which either the autopsy or eyewitnesses raised questions about the police account. The city also paid a man $100,000 after he claimed that two 6th District officers shot him and then planted a gun on him.

Abuses by 6th District officers outside the tactical team during Johnson’s time as commander also led to major misconduct payments and criminal cases. A jury awarded $750,000 to a woman beaten by a 6th District officer who accused the 20-year-old of violating curfew. An Internal Affairs investigation also found that 6th District officers, including a lieutenant, covered for a drunk officer named Richard Bolling — the son of a retired CPD commander — after he struck and killed a 13-year-old out riding his bike. One unidentified officer promised Bolling that “I’m gonna try to help you out as much as possible.” Sixth District officers on the scene waited over two hours to administer a sobriety test. Bolling was eventually sentenced to three years in prison.

The shootings and other misconduct allegations cost taxpayers millions. The Invisible Institute analyzed unit assignment data and a Chicago Reporter database that tracks all police misconduct payments from 2011 through 2016. Johnson’s 6th District was just one of 25 police districts but accounted for roughly $8 million, fully one-sixth of the entire CPD’s misconduct payments during his time as commander. Since the end of 2016, Chicago has paid at least another $3.7 million related to misconduct by 6th District officers during Johnson’s time as commander.

Over Johnson’s tenure, dozens of officers serving on the tactical team were involved in lawsuits that led to settlements totaling $6 million. That total accounted for a huge share of overall CPD misconduct payments, costing the city about $130,000 for each of the team’s roughly 45 officers — nearly 40 times the average for all other CPD officers.

Walker, the University of Nebraska police accountability expert, argues that Johnson’s handling of misconduct as a commander has a strong bearing on his role as superintendent. “It’s another reason why he’s probably not qualified for his current job,” he said. “He just doesn’t think in terms of these kind of problems or see them as problems and take corrective action. … He’s just not qualified to be the chief executive of a police department, especially one as large and complex as Chicago.”

Photo: Zbigniew Bzdak/Chicago Tribune/TNS via Getty Images

Johnson left the 6th District in August 2011, and from 2012 to 2014, he served as deputy chief of patrol for Area Central, directly supervising nine district commanders.

Johnson’s time as a deputy chief followed a similar pattern as his tenure as commander. He was credited with major reductions in gun crime and murders in 2013 (though only after a spike in 2012), while continuing to sign off on cases like the shooting of 17-year-old Christian Green. As the on-call incident commander in that shooting, Johnson took aside the four officers who witnessed the shooting and interviewed them one by one. The officers all gave Johnson similar accounts: Green had turned around and pointed a gun at pursuing officers, prompting one to return fire. Johnson also conferred with detectives on the scene. He did not speak with any civilian witnesses, he said in a deposition.

Security cameras captured images of Green running from the police and carrying a gun. At one point, Green tried to throw the weapon in a trash can, but it bounced out. Green hurried back to collect it before sprinting off again. Green and his police pursuers then moved out of the cameras’ view. Moments later, he was dead.

One of the pursuing officers had fired 11 shots at the teenager. An eyewitness later testified that the officer stood over Green’s body and shouted, “Motherfucker! You wanna run? Huh? Huh? … You see how fucking far you got?” The same witness said that Green was running away and not facing the officer when he opened fire. Green’s gun was found in an abandoned lot, 75 feet from his body.

Johnson approved the officers’ use of force. While on the scene, he also gave a walkthrough to investigators from IPRA, telling them that Green had been shot in the chest when he turned to point his gun at officers. An autopsy would later reveal that Green had been shot in the back.

Photo: Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune/TNS via Getty Images

In 2017, a jury found that the officer who killed Green had shot without cause and awarded his family $350,000. After the trial, the family’s attorney criticized the investigation overseen by Johnson, declaring that it “fell short on every level.”

Prior to the trial, Johnson testified in a deposition that he did not know that the shooter had previously belonged to a notorious crew led by Sgt. Ronald Watts. Just a year before Green’s shooting, Watts and his partner had been arrested for stealing money from an FBI drug informant. After Watts’s arrest, some questioned why the rest of his team — which included three of the four officers Johnson interviewed — remained on the street. Years later, as superintendent, Johnson placed all three on desk duty after Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx’s office found serious problems with over a dozen cases tied to Watts’s team, leading to the largest mass exoneration in Cook County history.

Aggressive officers like Glenn Evans also continued to receive Johnson’s support, even as allegations of excessive force followed him as he entered the highest ranks of the CPD. Evans took charge of the 3rd District in August 2012, becoming one of the nine district commanders who reported directly to Johnson. Former CPD Superintendent Garry McCarthy said in a deposition obtained by WBEZ that he likely promoted Evans based on a recommendation from Johnson, though Johnson has disputed this.

Evans ultimately garnered nine complaints in two years as a commander, an exceptional amount for a senior official, who tend to receive far fewer complaints than street-level officers. Only 23 of Chicago’s roughly 13,000 officers received more complaints. One of the complaints against Evans concerned a man named Ricky Williams, who claimed that in 2013, Evans cornered him in an abandoned building and shoved his gun down his throat. Johnson directly supervised Evans at the time, but he and McCarthy took no action — even when IPRA recommended Evans be stripped of police powers after finding Williams’s DNA on his gun.

Evans was eventually indicted over the Williams incident in the summer of 2014. After a controversial acquittal the next year, the department demoted him to lieutenant. During Evans’s brief time as a commander, his subordinates killed two teenagers in troubling circumstances. Investigators ruled one shooting unjustified — though Chicago’s Police Board recently overturned their ruling — and recently reopened an investigation of the second after finding video contradicting officer accounts from the scene. The first shooting — a 15-year-old named Dakota Bright shot in the back of the head — took place while Evans reported directly to Johnson and led to a $925,000 settlement paid to Bright’s family.

“CPD standard operating procedure is, and has been for years, when an officer is accused of misconduct, when an officer uses force, it’s to justify it and circle the wagons and get the officer’s back,” said civil rights attorney Craig Futterman. “You don’t even need a conspiracy, it’s just standard operating procedures, and [Eddie Johnson] has been a part of that for 30 years.”

In response to a detailed list of questions for this article, Johnson provided the following statement:

During my entire career with the Chicago Police Department I have and will always approach every decision, action and investigation with the highest level of integrity and thoughtful deliberation of available facts and evidence. The trust between police and the community is paramount to everything we do and it is vitally important to me as the Police Superintendent and as a lifelong resident of Chicago. Since becoming Superintendent, I implemented a comprehensive reform agenda to solidify CPD’s path toward becoming a model agency that all of Chicago could be proud of. I support the federal consent decree and have embraced and advocated for investments into our police officers including, better training, support and mentoring. I also reinvigorated our community policing philosophy because CPD is only as strong as the community’s faith in our officers and we cannot create a safer Chicago without standing shoulder to shoulder with the people that live and work here.

All of the use of force incidents you reference have gone through an independent use of force investigation, a review by state or federal prosecutorial agency and independent deliberation by the then-Superintendent and Chicago Police Board. All of the answers to your inquiries can be found in the publicly available case records and court transcripts for those incidents.

Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images

Johnson took charge of the CPD in 2016, the same year Chicago endured a massive increase in homicides, with the murder rate jumping nearly 60 percent. Though homicides declined in 2017, they remained well above historic levels. Other types of crime also rose, with reported carjackings more than doubling between 2015 and 2017.

In the first months of his tenure, Johnson moved to implement some of the mayor’s key reform promises, greatly expanding the use of body cameras and supplying Tasers to more officers. The department rewrote its use of force rules, which reform advocates largely praised. Johnson also responded to some police shootings more forcefully than his predecessors, immediately suspending officers in a handful of officer-involved shootings, including a case in which an officer killed an unarmed teenager named Paul O’Neal.

But in the context of rising violence, calls to let the police return to their old ways are growing louder. Addressing the possibility of court oversight of the CPD, Fraternal Order of Police President Kevin Graham last year declared, “Already facing an explosion of crime because the police have been so handcuffed from doing their job by the intense anti-police movement in the city, this consent decree will only handcuff the police even further.”

Former CPD Superintendent Garry McCarthy, now running for mayor, has voiced similar sentiments, denouncing the DOJ report and insisting that “the problem in Chicago is not the police.”

Faced with pressure from within his own ranks, Johnson has returned to a familiar approach to police shootings. He defended Officer Robert Rialmo, who shot and killed Quintonio LeGrier, a college student in the midst of an emotional disturbance, and Bettie Jones, a 55-year-old bystander, sparking pushback from several African-American aldermen. Johnson’s move to prevent Rialmo’s firing came after he also sought to block the firing of the officer who shot and killed 15-year-old Dakota Bright.

Two and a half years into Johnson’s appointment, Chicago’s police department is far from reformed. Three separate lawsuits filed last year — one by a broad civil rights coalition, including the Chicago branches of Black Lives Matter, the NAACP, and the Urban League, represented by civil rights attorneys Craig Futterman and Sheila Bedi; one from the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois and community groups such as the Community Renewal Society; and one from Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s office — all insisted that only court-overseen reforms will truly change the department. (Andrew Fan provided pro bono data analysis of a CPD use of force database to the first coalition suing the CPD).

The Madigan lawsuit pushed Mayor Rahm Emanuel to begin negotiations to accept formal court oversight of police reforms in Chicago. In July, Madigan and Emanuel announced a 225-page draft consent decree that outlines sweeping changes that the department must complete in the coming years.

In early September, Emanuel’s announcement that he would not run for re-election jolted the mayoral race, prompting many of Chicago’s most prominent politicians to consider jumping into the contest. Many observers pointed to the approaching trial of Jason Van Dyke, the officer who killed Laquan McDonald, and the likelihood of renewed public attention toward Emanuel’s record on police misconduct as a key factor in his decision to step down.

Still, Emanuel will remain in office for over six months, during which time the city will finalize and begin to implement its historic court-ordered reforms. Emanuel’s unwillingness to embrace police reform is now as important as ever, with the mayor in a position of power but unconstrained by the threat of an election. Despite his repeated reform promises, in the wake of Donald Trump’s inauguration, Emanuel sought to strike a deal with then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions that would have staved off court oversight of the CPD. Even after public pressure ended that effort, Emanuel spoke openly of his fear that reform could worsen the city’s crime rate, worrying that “other cities have done this to the police department and it’s come at the expense of public safety.”

The support of Emanuel and Johnson is crucial even with a formal consent decree. Chiraag Bains, a former DOJ attorney who worked on the federal investigation of the Ferguson, Missouri, police department, argues that “the orientation of the political leadership and the leadership of the police department are key to whether the reform process is successful or not.”

Futterman echoed Bains’s point, but lamented that “sadly under this administration, I’m seeing the antithesis of that. A failure to own [the problem] and a lack of genuine commitment to address the realities that brought the DOJ to Chicago in the first place.”

Photo: Todd Heisler/The New York Times via Redux

The problems posed by Eddie Johnson’s leadership extend far beyond the mayor who appointed him. When Emanuel appointed Johnson in early 2016, his hold on the mayor’s office was in jeopardy. After the release of the Laquan McDonald video, one poll showed that a majority of Chicago voters wanted him to resign. The selection process was a rare opportunity for Chicago’s City Council and the media to check the mayor during a moment of weakness, especially after the mayor picked an insider to run the police department even as he promised Chicago “nothing less than complete and total reform of the system.”

Rather than digging into Johnson’s record, political leaders and media outlets, in a deeply familiar Chicago process, instead fixated on Johnson’s political ties and loyalties. A Chicago Tribune editorial congratulated Emanuel on the politics of the pick, noting that “the mayor scored the support of the Black and Latino caucuses and the Fraternal Order of Police, a rare trifecta.”

None of the city’s major news outlets connected Johnson to his role in approving Rekia Boyd’s killing, despite devoting major coverage to Dante Servin’s trial less than a year prior. Chicago media also failed to report on Johnson’s record as a senior CPD leader, including the troubling pattern of killings hanging over his time as commander of the 6th District. Chicago’s aldermen, fresh from helping to push out McCarthy for his role in the McDonald shooting, approved Johnson by a vote of 50-0.

Chicago will soon decide on new leadership for the city and its police. With Emanuel’s retirement, voters have a wide range of options, including Garry McCarthy, Bill Daley — brother and son of former Chicago mayors — and Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, a supporter of police reform who once condemned McCarthy as a “racist bully boy.” With neither an incumbent nor an obvious frontrunner, the city faces perhaps its most wide-open mayoral contest since 1983.

Six years after Rekia Boyd’s killing jolted Chicago activists and three years after video of Laquan McDonald’s shooting channeled activist anger into a citywide movement, Chicagoans face a momentous choice on police reform.

How to fix Chicago’s police is a longstanding and difficult question, but this time the decision lies not in the hands of a powerful mayor, but with the people of Chicago.

This story will appear on the cover of next week’s issue of South Side Weekly, a nonprofit newspaper based on Chicago’s South Side.

Roman Rivera contributed data analysis.

The post Chicago Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson’s Long Record of Justifying Police Misconduct and Shootings appeared first on The Intercept.

Subscribe to the Intercepted podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, Radio Public, and other platforms. New to podcasting? Click here.

Donald Trump is waging a political counterinsurgency. This week on Intercepted: Columbia University professor Bernard Harcourt lays out the multidecade history of paramilitarized politics in the U.S., how the tactics of the war on terror have come back to American soil, and why no one talks about drone strikes anymore. Academy Award-winning director Michael Moore talks about his recent visit from the FBI in connection to the pipe bomb packages and who he thinks should run against Trump in 2020. Journalist and lawyer Josie Duffy Rice analyzes the battle over vote counts in Florida and Georgia, the Republican campaign to suppress black voters, the gutting of the Voting Rights Act, and why she isn’t protesting the firing of Jeff Sessions. Jeremy Scahill explains why Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer need to go away.

Transcript coming soon.

The post Donald Trump and the Counterrevolutionary War appeared first on The Intercept.

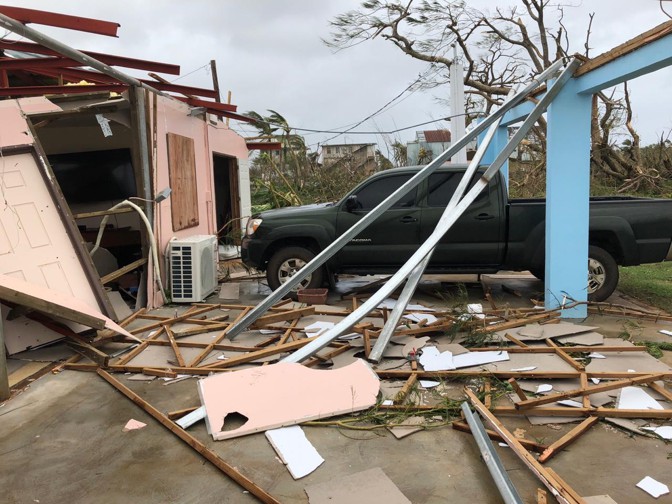

Yutu: Or, what we weren’t following: A super typhoon that destroyed the U.S. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands several weeks ago was a relative blip in U.S. media coverage. Tens of thousands of Americans were affected—what happened while few eyes were turned to the region?

Deal or No Deal: The original referendum on Brexit took place more than two years ago. Since then, the actual process of leaving has been throttled by impasses, infighting, indecision, and resignations. Britain is poised to leave the European Union in fewer than 140 days. What does the embattled U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May now need to do to pass her plan for Britain’s life after the EU? And what will hold up the deal before the finish line?

Private Practice: Kim Kardashian and Kanye West reportedly hired private firefighters to help save their home and neighborhood as wildfires continue to burn across swaths of California. Celebrities aside, the incident has spotlighted the American system of privatized firefighting operations. Another often forgotten contribution to firefighting efforts: prison inmates.

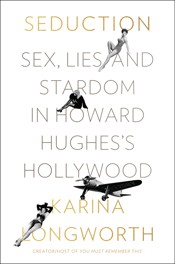

Snapshot The writer and critic Karina Longworth injects new life into the stories of classic cinema, and the myths and stars of Old Hollywood, through her podcast, You Must Remember This, introducing a new generation to forgotten figures—including many women whose talents had been overshadowed in most retellings of the history of the entertainment industry. Sophie Gilbert profiles Longworth and explores how she came to have such a cult following. (Image collage by The Atlantic)Evening Read

The writer and critic Karina Longworth injects new life into the stories of classic cinema, and the myths and stars of Old Hollywood, through her podcast, You Must Remember This, introducing a new generation to forgotten figures—including many women whose talents had been overshadowed in most retellings of the history of the entertainment industry. Sophie Gilbert profiles Longworth and explores how she came to have such a cult following. (Image collage by The Atlantic)Evening ReadPresident Donald Trump’s appointment of Matthew Whitaker as acting attorney general goes against the U.S. Constitution, argues John Yoo, who was deputy assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush administration and has been known for his expansive view of presidential powers:

Whitaker’s appointment must still conform to a higher law: the Constitution. As the Supreme Court observed as recently as this year, Article II provides the exclusive method for the appointment of “Officers of the United States.” The president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States.” The appointments clause further allows that “the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments.”

Read the rest of Yoo’s reasoning.

What Do You Know … About Science, Technology, and Health?1. Every year, American cities and states spend upwards of how many billion dollars in tax breaks and cash grants to encourage companies to move among states?

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

2. When Jeff Sessions was forced to resign last week, stock prices for businesses in which industry went up?

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

3. Where did the Camp Fire, the deadliest and most destructive fire in California state history, get its name?

Scroll down for the answer, or find it here.

Answers: 90 / cannabis / Where the fire started: On Camp Creek Road

Looking for our daily mini crossword? Try your hand at it here—the puzzle gets more difficult through the week.

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Atlantic Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

Written by Elaine Godfrey (@elainejgodfrey) and Olivia Paschal (@oliviacpaschal)

Today in 5 LinesHouse Republicans elected Representative Kevin McCarthy as minority leader. Senators Mitch McConnell and Chuck Schumer were each reelected to their respective positions as Senate majority leader and minority leader. House Democrats will vote for Speaker of the House later this month.

The Trump administration defended its choice to revoke CNN reporter Jim Acosta’s press pass in a court filing, asserting that it has “broad discretion” to limit reporter access to the White House.

The Justice Department issued a memo stating that the appointment of Matt Whitaker as acting attorney general is constitutional. President Donald Trump chose Whitaker to replace Jeff Sessions last week.

Democrat Andy Kim officially defeated Republican Representative Tom MacArthur in New Jersey’s third district. Democrats have brought their House gains to a net total of 34 seats, and that number could increase, since several more races are undecided.

Trump announced his support for The First Step Act, a criminal-justice reform bill that has already passed the House.

Today on The AtlanticMeet Peter Navarro: He’s the madman behind President Trump’s “madman theory” approach to trade policy, and one of the most important generals in the U.S.’s trade war with China. (Annie Lowrey)

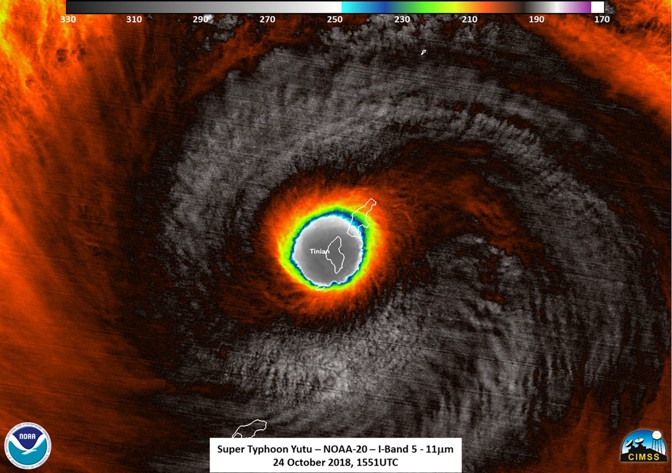

Who Booted Scott Walker?: Early data shows that increased black and Latino voter turnout might have helped defeat Scott Walker in last week’s midterm elections. (Vann R. Newkirk II)

Part of a Broader Pattern: On October 25, a super typhoon struck the Northern Mariana Islands and left thousands homeless. U.S. media outlets barely covered it. (Alia Wong and Lenika Cruz)

Not All White Women: After the midterms, many progressives held white women responsible for several high-profile Democratic losses. But the actual results were more nuanced, argues Conor Friedersdorf.

Still Waiting: A dramatic intervention by the Vatican at this week’s conference of American Catholic bishops highlighted the difference between Rome and the United States on how to address the Church’s ongoing sex-abuse crisis. (Olivia Paschal)

Who’s Responsible?: Americans are too quick to place moral blame for political violence on public figures, argues David French: “To hold anyone morally responsible for acts he did not condone, encourage, or seek...is to risk becoming what we hate.”

Snapshot Jason Coffman, right, father of Cody Coffman, is comforted by Anthony Ganczewski at a funeral service for his son in Camarillo, California. Cody was among a dozen people killed in last week’s shooting at a country music bar in Thousand Oaks, California. (Jae C. Hong / AP)What We’re Reading

Jason Coffman, right, father of Cody Coffman, is comforted by Anthony Ganczewski at a funeral service for his son in Camarillo, California. Cody was among a dozen people killed in last week’s shooting at a country music bar in Thousand Oaks, California. (Jae C. Hong / AP)What We’re ReadingThe Vaporware Presidency: More than any president before him, Trump is an expert in saying he’ll do things that never end up happening. (Jonathan V. Last, The Weekly Standard)

Eyes on Miami-Dade: While an overall strong showing for Democrats, the midterms reveal several of the party’s weak spots going into 2020. (Nate Cohn, The New York Times)

A Conscious Uncoupling: Heading into 2018, the new Congress is more divided than ever. Is it time to split up the states? (Sasha Issenberg, New York)

An Activist Lineage: You can’t understand Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez without understanding the long history of Latino organizing in New York, writes Pedro Regalado. (The Washington Post)

VisualizedWhat’s Left?: These are the races that have yet to be called, over a week after the midterm elections. (Emily Stewart, Vox)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Old habits die hard.

As House Republicans settle into their new status in the minority—a post in which members typically unify to obstruct policy proposals from the majority—intraparty tensions remain as strong as ever, and could spell trouble for the GOP’s efforts to reclaim the chamber sooner rather than later.

In a conference-wide election on Wednesday, Republicans anointed their leaders for the 116th Congress. Outgoing Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy won minority leader with 159 votes, besting House Freedom Caucus co-founder Jim Jordan, who won 43. Rounding out the party’s top three positions, Republicans also elected Steve Scalise as minority whip and Liz Cheney as conference chair, a position once held by her father, former Vice President Dick Cheney.

“We serve in a divided government, in a divided country,” McCarthy told reporters following his election. “Our goal is to unite us back together again.”

McCarthy might have added that he serves not just in a divided government and country, but also in a divided party. In the last week, many of the ideological factions that have stymied House Republicans’ legislative efforts in recent years also threatened to complicate McCarthy’s rise. The California Republican had long been the favorite to lead the conference. Even so, conservative members and outside groups spent their post-midterm days attempting to gin up support for his challenger, Jordan, a perpetual gadfly of House Republican leadership. And, as Politico first reported on Wednesday, McCarthy faced overtures from President Trump himself to help Jordan acquire a prominent committee post following his expected failed bid for minority leader.

Nevermind that McCarthy has little say in committee leadership, something determined by the committee members themselves. The implication of Trump’s move was clear: Even in the minority, the lower chamber’s most conservative members will still attempt to exert whatever influence they have left over their leadership. It’s a sign that House Republicans could struggle even in the most basic tasks of unifying against the Democrats’ legislative agenda. And as Democrats consider opening investigations into the executive branch, that could mean trouble not only for Trump, but for the GOP’s attempts to reclaim the majority in the speedy timeframe McCarthy said he hopes for.

A telling sign that conservatives still intend to make life difficult for leadership came on Tuesday night, when candidates gathered to make their pitches to the conference. According to two sources in the room, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the gathering, conservatives lobbed a round of hostile questions at McCarthy after he laid out his vision for the next year. Texas Representative Louie Gohmert, the sources said, accused McCarthy of “spending money to promote himself over the team” ahead of the midterm elections. Gohmert cited ads that aired on conservative radio promoting McCarthy’s Build the Wall, Enforce the Law Act, largely seen, among even Republicans, as a show bill to fund Trump’s border wall. The sources said Gohmert criticized McCarthy for “talking up” the wall even as Republicans had failed for two years to adequately fund it.

That grudge will likely carry into the lame-duck session over the next two months, where in their last days in the majority, Republicans will have to cobble together a funding bill in order to avoid a government shutdown. During a conference meeting on Wednesday morning, according to two sources in the room who asked not to be named because of the private nature of the meeting, a handful of conservative members echoed Gohmert’s remarks from the night before, arguing it was incumbent upon leadership to take wall funding and other immigration measures seriously while they still have the chance.

In other words, McCarthy will round out his time as majority leader engaging in the same battles he’s fought for two years now: attempting to placate Trump and his allies’ desire for aggressive action on immigration, while putting together a funding bill that can pass muster with the rest of his conference. He’ll avoid those responsibilities as minority leader once the next Congress begins. But, as Gohmert indicated, he may still enjoy the ire of conservatives who believe leadership lost them meaningful progress on immigration—and control of the House altogether.

Following the leadership elections on Wednesday, McCarthy acknowledged his party’s crushing defeat to reporters. He noted that Republicans had lost ground in suburban areas, and suffered for it in the midterms.

But neither he nor any other Republican leader mentioned Trump by name, or engaged in good faith with the question of just why the party had, for example, lost ground in the suburbs. Instead, McCarthy and Scalise explained their loss by stressing that “history was working against [them],” citing the fact that the president’s party usually loses control of one or both chambers of Congress in the first midterm election after he or she takes office.

Even if GOP leadership can expect intraparty scuffles in the months to come, they made clear that Democrats would surely face the same. Jason Smith, the newly elected conference secretary, alluded to the youth crisis, of sorts, roiling the soon-to-be majority. “This team right here, the average age of all of us combined is 52 years old,” he said. “The average age of the top three leading candidates on the other side is 78 years old.” Republicans may not have maintained control of the chamber, Smith seemed to suggest, but they had fresh faces ready to take over the next time they do.

And in an apparent acknowledgement of reports of party fissure, McCarthy told reporters after his victory that he hoped the early date of their leadership elections would signal Republican unity. “It’s healthy to have a debate,” McCarthy said. “I want to thank Jim Jordan for running.”

With all the problems plaguing America today, it can be difficult to prioritize which to address. But just because a problem may not be headline-worthy doesn’t mean it isn’t a problem.

Take gas-powered leaf blowers, for example.

In a new Atlantic Argument, writer James Fallows advocates for phasing out the machines—which emit noise up to a dangerous 112 decibels—in favor of quieter and safer battery-powered leaf blowers.

This shift, says Fallows, “has community interest, worker interest, public health, and technological momentum on its side. To really ‘make America great again,’ we need to ban gas-powered leaf blowers.”

As the mail-in votes are counted and the recounts finished, the Democratic advantage in the 2018 elections grows and grows.