MANILA—All Jefferson Soriano wanted was to go to bed. But the power was out, his tiny room felt like a furnace, and his friend Manuel Borbe had come by. The pair walked outside to chat and get some air, eventually stopping for a late-night coffee along a busy road.

Soriano and Borbe had lived nearly their entire lives in the area, a shantytown in a Manila community called Holy Spirit, and had met as teens on a neighborhood basketball court. They had been friends ever since, growing up together, and now both were new fathers in their 30s struggling to make ends meet—Soriano by working odd jobs in grocery stores and fast-food restaurants, Borbe as a construction worker.

At the time, Rodrigo Duterte’s first year as president of the Philippines was coming to a close, a violent period during which the government prosecuted a war on drugs, in which police swept down, arrested suspected drug sellers, and conducted sting operations against them. Officers were given wide latitude to shoot, and kill, suspected drug dealers—ostensibly in self defense—and Holy Spirit was one of the offensive’s epicenters.

Soriano and Borbe had themselves been caught up in police raids: The former had been reported for his contact with drug dealers, the latter had previously surrendered to police and admitted that he was a user of crystal meth, or shabu. In fact, just a month before, policemen had barged into Soriano’s home while he was in the bathroom naked and dragged him outside as he begged for his life. They took him to the police station and, he says, beat him as they questioned him about his association with drug dealers.

So that night—June 15, 2017—Borbe was anxious, worried for his wife and infant son were he to be arrested, or worse, killed. “My time,” he told Soriano as they sipped coffee, “will soon be up.”

While they sat and chatted, a car drove past, its headlights casting a glow on a tall, well-built man standing on the corner on the opposite side of the street. He was soon joined by another man, who arrived on a motorcycle. Each was clad in the same attire—a dark jacket, shorts, and a balaclava.

“Bro, cops,” Soriano told Borbe, believing that the men, despite their face coverings, were police officers. Their stocky build, their posture—hands on their sides, as though they were about to draw their guns—reminded him of the many policemen he’d had run-ins with over the years. Before either friend could do anything, one of the men raised his arm and fired a pistol. Borbe slumped to the ground, taking a fatal shot to the head. Soriano tried to run, but other shooters were waiting at nearby street corners, and fired at him from different directions, hitting him in the neck and leg. As he lay bleeding on the pavement, pretending to be dead, Soriano recalls, he heard the gunmen mount their motorcycles to flee, only for one of the bikes not to start, forcing two of the men to push it downhill to get away.

“The only thought I had in my mind then,” he said in an interview this year in Manila, where he is in hiding, fearing for his life, “was that I had to live for the sake of my son.”

Borbe’s death was posted on the police blotter and investigators were sent to the scene. Journalists arrived shortly after and reported the incident in the news. Photographs were taken, showing Borbe’s corpse splayed on the street corner, the blood from his head wound flowing into the storm drain.

Yet this well-publicized killing is not included in any official count of drug casualties. It has not been fully investigated. It is unclear who the shooters were. As we have found, that is far from unusual: Borbe is only one among a huge number of uncounted victims of Duterte’s drug war.

Elected in 2016 pledging to crack down on drug use, Duterte has now passed the halfway point of his six-year presidency. In that time, the president has employed populist tactics such as naming and shaming 150 judges, mayors, and police generals he says coddled drug dealers and releasing a list of 46 government officials running for office he claims were involved in illegal narcotics. Local officials across the Philippines are required to list suspected drug users and monitor their progress kicking the habit, while police stations must maintain watch lists of alleged drug suspects who are under surveillance. Duterte has assured the police that he has their backs, telling them, “You are free to kill the idiots” who violently resist arrest.

By some measures, that is having a positive impact: The overall national crime rate went down 20 percent in the past two years (though murder rates have gone up). And politically, this muscular approach to the drug problem has been a windfall for Duterte. His approval rating is close to 80 percent, and in midterm elections to the Senate in May, candidates who backed his drug war fared well, topping the polls even in the shantytowns where suspects were being gunned down.

But at what cost? The police say they have killed some 5,500 drug suspects in stings and other legitimate police operations in the past three years, and that unknown gunmen have killed more than 3,000 other drug suspects, amounting to a tenth of the nearly 30,000 homicides carried out in the Philippines since Duterte’s drug war began. (The police blame the drug-linked killings on narcotics syndicates; human-rights groups say these executions are often the work of off-duty cops or hired guns on the police payroll.)

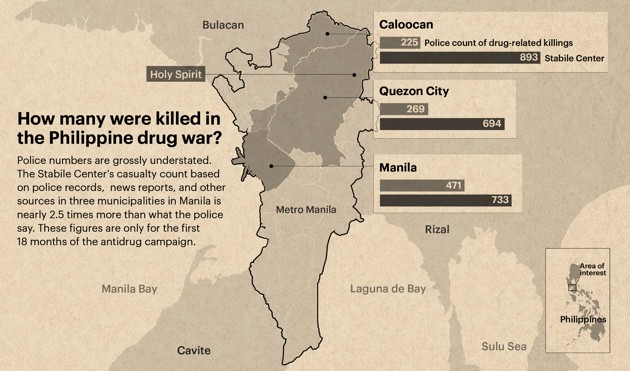

An investigation carried out by the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism shows, however, that these figures are a gross underestimation of the extent of drug-related killings in the Philippines. The data we have collected—based on documents and reporting on homicides, as well as multiple visits to neighborhoods where the killings took place—illustrate how large numbers of killings of drug suspects, by both police and unidentified shooters, have been excluded from official counts: In three municipal areas of Metro Manila, the sprawling Philippine capital of 13 million people, our data show that half of all homicides recorded by the police were tied to illicit narcotics, contrary to police claims that only a small proportion were related to drugs. In addition, we found hundreds of homicides that were not on the police record at all.

This discrepancy goes beyond a question of correctly labeling or reporting incidents of violence, and instead points to concerns about how this war on drugs is being carried out. Is what is taking place in the Philippines an anti-crime campaign, or something darker, in which large numbers of people are being denied due process, targeted for assassination, and offered little in the way of help to quit drug use, while the underlying issues driving the problem are left unaddressed? Filipinos themselves said soon after Duterte took office that, while they applauded the push against narcotics, it was important that suspects be arrested, not killed.

This has implications beyond the Philippines, too. Responding to concerns about the “staggering number” of drug-related deaths in the country, the United Nations Human Rights Council voted last month to investigate the killings, and the International Criminal Court is looking into charges that Duterte and other officials have committed crimes against humanity. Other countries, including Indonesia, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, are looking to the Philippines as a model for fighting drugs, but would they be so positive about Duterte’s strategy if they knew the true body count?

The Philippine leader has dismissed any concerns about whether his plan is the right one, arguing that drug users eventually graduate to more violent crime, and so cracking down on them saves lives overall. “Your concern is human rights,” he railed in a fiery speech last year. “Mine is human lives.”

According to the Manila police’s own guidelines, homicide victims who are reported to be involved with drugs or who are found with drugs or drug paraphernalia in their possession, and when no other motives could explain their death, should be classified as drug-related fatalities. Based on those standards, the police say that from July 2016 to December 2017, when the antidrug campaign had just begun and was at its most intense, 965 people were killed by gunmen or police officers in the three Metro Manila “cities” we focused on: Manila, Quezon, and Caloocan, which cumulatively account for roughly half of the capital’s population.

Our reporting shows, however, that the real death toll is actually far higher. We cross-referenced the police’s own data against news stories, police blotters as well as spot and incident reports, and memos on police shootings submitted to the internal-affairs department at the national police headquarters. We compiled lists of casualties with the help of church groups, human-rights organizations, academic researchers and journalists, as well as the Commission on Human Rights, a national watchdog. And we reviewed a database of drug-war casualties that researchers at the Ateneo School of Government constructed using news reports.

In all, we built a list of fatalities based on 23 different sources and visited four communities in the capital to verify the information. To be included on our list, a homicide victim needed to have a history of alleged drug use, been a drug user or seller, been listed on a drug watch list, or been accused in a drug-related case. In the majority of cases, this information was found in news reports, police records, and survivor testimonies. In some cases, killings were executed in the trademark style of drug-linked homicides—armed assassins wearing balaclavas on motorcycles or other vehicles—but there was no information on the victim’s drug links. We included 80 of these that were recorded in police documents, because they took place in neighborhoods where many similar killings had occurred.

Overall, we collected information on 2,320 drug-linked homicides in the first year and a half of Duterte’s drug war—more than twice as many as the police have claimed, a difference of some 1,400 lives in just three parts of the Philippine capital.

One reason for the gulf is that some killings are clearly improperly categorized. Borbe’s death, for example, was not listed as drug-linked but as a “homicide under investigation,” a label under which many cases languish for years. Fewer than 80 drug-related killings have been prosecuted by the country’s Department of Justice since Duterte took office. Countless others, including Borbe’s, remain unsolved. Guillermo Eleazar, the top police officer in the Manila region, told us that proper categorization was not important. “We respect the judgment of the investigator assigned to the case,” he said. “For our purposes, it doesn’t matter whether a case is drug-related or not.” Then he added: “We all know that drugs are the root of all crime.”

The police have also, notably, offered an inconsistent account of how many drug users have died at the hands of their own officers. In June, they said that 1,180 people had been killed across Metro Manila in the preceding three years, yet in mid-2017, the country’s then–police chief published a glossy report saying that more than 1,200 “drug personalities” had been killed in the capital in the previous year alone. When we asked about this difference, the police said that they could not ascertain the source of the police chief’s report and that “local police stations regularly update their records,” causing changes in the data. Each time we asked for clarity, we were sent new figures that conflicted with previous ones. And in interviews we conducted in the past two years, police commanders cited much higher casualty counts than what the current numbers show.

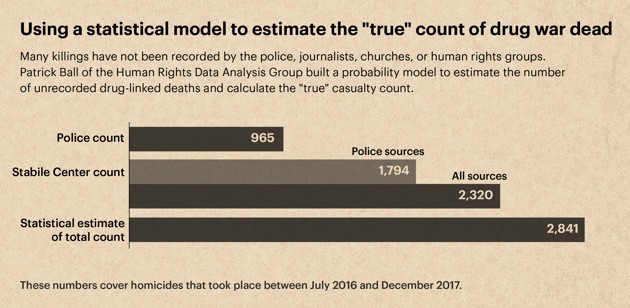

In fact, if anything, our casualty count may even be an underestimate. Many killings are not recorded by the police or by journalists, and the churches and human-rights workers that document the dead have limited reach.

Patrick Ball, a statistician with the Human Rights Data Analysis Group in San Francisco, used machine learning to analyze the various lists we obtained in building our own tally, relying on a technique called “multiple-systems estimation” to count undocumented conflict-related deaths, essentially comparing information from multiple data sets and inferring what was not recorded. He has previously estimated casualty counts in conflicts in Syria and Guatemala, predicted the locations of graves of missing victims of Mexico’s drug war, calculated the death rate of political prisoners in Chad, and served as an expert witness in international tribunals. (In one notable case, his testimony helped convict Guatemala’s General Efraín Ríos Montt of genocide.)

Based on Ball’s calculations, using our data, nearly 3,000 people could have been killed in the three areas we analyzed in the first 18 months of the drug war. That is more than three times the official police count.

Methamphetamine began trickling into the Philippines in the late 1980s. It was initially smuggled in from China, but then later began being manufactured locally and was sold to all manner of people—seasonal construction workers, taxi drivers, grocery baggers, waiters and busboys on short-term contracts, and call-center workers who labored around the clock, using shabu to stay alert. Shabu is the poor man’s drug—the rich, according to Duterte, prefer cocaine or heroin, both of which he considers safer and “not as destructive” as crystal meth.

But unlike in Central America, where drugs are sold by armed gangs, most shabu peddlers here are ordinary men and women for whom selling tiny sachets of meth is more akin to a side business, like hawking cigarettes or newspapers to help pay for food or school fees. Police and officials long ignored the trade, or at times even profited off it, protecting smuggled shipments of drugs as they were trafficked through the country’s porous ports.

It was this web that Duterte’s drug war sought to hit, and among the neighborhoods that were targeted was Holy Spirit, a network of densely packed alleys with one of the highest concentrations of drug-linked killings in Manila.

Holy Spirit, named after the order of nuns who set up a school for girls in a gated community in the 1970s, lies just a couple of miles away from the Philippines’ House of Representatives building and is a sprawling area that, in effect, houses two communities, each living parallel yet separate lives. The neighborhood’s gated villages have wide, tree-lined streets and are replete with their own churches, parks, and shopping areas, while residents have access to clubhouses and swimming pools. A short walk away, however, lie squalid squatter settlements, with families living in closet-size dwellings built along unpaved alleys. The streets are crowded, doubling as basketball courts, markets, and karaoke parlors.

At the start of the drug war, in mid-2016, Eleazar, the current Metro Manila police chief, was put at the helm of security in Quezon City, the municipality where Holy Spirit is located, replacing an officer accused of protecting drug dealers. He reshuffled five of 12 station commanders and exiled one to the southern island of Mindanao, then removed policemen who had allegedly been extorting money from drug suspects and brought in new officers willing to take the lead in the drug war.

The changes were welcomed in Holy Spirit. “That was the first time I saw the police were actually doing their jobs,” says Felicito Valmocina, the tall, lanky longtime kapitan of the Holy Spirit local council. The year before Duterte came to power, 321 crimes were recorded on the police blotter in the neighborhood—mostly thefts and robberies, but also 19 homicides. Valmocina claims that the shabu trade thrived in his community because cops were themselves the drug’s suppliers and the police looked the other way as shabu was traded in the open.

The drug war changed that. Police began making the rounds, focusing on the poor parts of Holy Spirit, areas where many, such as Soriano, still lived with their parents. Residents were encouraged to rat on their drug-using and drug-dealing neighbors by submitting anonymous reports in boxes. Based on these reports and on information gathered by neighborhood watchmen in the local council’s employ, Holy Spirit officials put 187 people on a watch list, knocking on their doors to warn them of the impending crackdown. Still, Valmocina says, many persisted in using shabu, and so while he wishes they were not killed, either by police or masked gunmen, the drug trade was so widespread that something needed to be done. The shift in policing tactics certainly had an impact: In the first year of Duterte’s new strategy, some 20 fewer crimes were recorded in Holy Spirit—but of the overall total, 58 were homicides, a threefold increase.

In Valmocina’s telling, many Holy Spirit residents accepted that trade-off. At the wakes of people who were killed, he would ask those in attendance how they were coping. “They’d say, ‘Ay kapitan, we’re grateful we have one less. That guy was a big headache,’” Valmocina recalls. “In none of the wakes I’ve been to has someone said, ‘Kap, why did they have to kill him?’”

“No one has complained to me,” he continues. “They say, ‘This is good.’”

Meth use in the Philippines is lower than in nearby Thailand and the United States, but Duterte has talked up the threat of drugs, stoking Filipinos’ worries about their safety, and it has made an impact. He remains popular, and his recent electoral success indicates that he retains a mandate.

Yet there is nevertheless significant disquiet among survivors of shootings, rights groups, and parts of the religious community. There are questions of legality (do the police have the right to embark on such an expansive drug war, seemingly curbing due process en route?); morality (is there not an obligation to try to help people kick their habit, rather than killing them outright?); and fairness (the majority of the victims are poor, young men—Noel Abecendario, a retired army sergeant who is now the head of public safety in the Holy Spirit district, acknowledges that richer suspects are pursued “up to the village gates, but the homeowners won’t let us in.”).

When Soriano left the hospital, he returned home and rarely ventured outside, afraid that gunmen would come for him again but lacking the funds to flee the neighborhood. Soon after, two middle-aged women knocked on his door to warn him that his life was in danger, and offered their help. They were part of a clandestine group of Catholic church workers and human-rights defenders providing sanctuary to drug-war victims and witnesses, and linked him with lawyers who filed for a writ of protection on his behalf at the national Supreme Court. At the end of 2017, months after he was shot, Soriano—then still recovering from multiple surgeries and walking with crutches, barely able to speak—briefly surfaced from hiding and appeared before the high-court justices as one of several petitioners asking that the government’s antidrug campaign be declared unconstitutional.

Finally, in April, the court partially agreed, ordering the government to submit police documents related to the antidrug campaign, including a list of casualties of drug-linked homicides. It was a rare victory. Undeterred, Duterte warned in May that the last three years of his term would be “the most dangerous time” in the war on drugs.

In Holy Spirit, the streets are now quieter. The killings by both police and gunmen wound down after the officers who were initially brought in were assigned elsewhere in late 2017. Most of the killings now take place in nearby provinces, and no longer in the capital. This year, Holy Spirit recorded four murders, none of which appears to be related to drugs, and local officials and church leaders have put a few dozen drug users in rehab.

But the drug trade continues. Sandie Caparroso, the barrel-chested major who heads the local police station’s antidrug unit, was raised in Holy Spirit and knows the area well. “What we know is that when we catch one seller, another one takes his place,” he says. Caparroso estimates that his officers have seized fewer than 10 kilograms of shabu since the drug war began, a relatively paltry figure, given the number of killings. And the costs of that brutal early period are still being counted. The high death toll in such a short time span overwhelmed human-rights groups, which lacked the resources to document so many cases.

Not far from the Holy Spirit police station, simple memorials to the drug war’s dead are tucked away in dark corners of the tiny cinder-block houses that line the alleys of squatter colonies. These shrines feature badly reproduced photographs of the departed, many alongside a rosary or statue of the Virgin Mary. In one, a pear was still wrapped in plastic netting; beside it was a single rose and a mug of coffee.

Among the victims was Jerwin Rivera. Well known in the neighborhood for organizing basketball games and emceeing local gatherings, the 36-year-old was charming, chatty, and popular among his neighbors. He worked construction jobs when they were available, and briefly for political campaigns. But Rivera also dealt shabu and, when the drug war began, surrendered to the local council, believing that he would be safe if he came clean and went into rehab.

In November 2016, while playing cards at a neighbor’s house, more than two dozen policemen charged in and shot him dead. Officers say they opened fire because Rivera shot at them, but his father, Ulysses, told us that his son was not armed. His death was one of dozens of drug-related killings that took place in Holy Spirit in the first two years of the drug war, but many victims’ surviving relatives have been too fearful or wary of the police to even dare ask why their loved ones were killed. Ulysses, an ailing former carpenter in his mid-70s, has been an exception.

“I’ve been telling him for a long time to stop selling,” he told us, referring to his son. “Why didn’t they give him a chance? Why didn’t they charge him first, sentence him, and jail him? If once he’s out, he still hasn’t changed, then they can go ahead and kill him. But why him? Why my son?”

This report was funded by the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Additional research was provided by the Security Force Monitor, a project of the Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute, and the Human Rights Data Analysis Group in San Francisco.

No comments:

Post a Comment