CHEMNITZ, Germany—One year ago, violent anti-immigrant protests turned this German city near the Czech border into a worldwide symbol of racial intolerance.

But on a recent summer evening, under the massive Karl Marx monument that served as a meeting point for far-right marchers back in 2018, hundreds of residents turned out to cheer on a politician with a very different message.

Robert Habeck, the 49-year-old leader of the German Greens and, according to some polls, the most popular politician in the country, ahead of Chancellor Angela Merkel, is taking his party’s progressive message on climate change and social cohesion to the heart of the former Communist East ahead of three state elections here that could shake up German politics and resonate beyond the country’s borders.

Chemnitz, in the state of Saxony, is hostile territory for the Greens. When the state votes on Sunday (the neighboring region of Brandenburg will hold an election on the same day, followed by Thuringia at the end of October), the big winner is expected to be the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

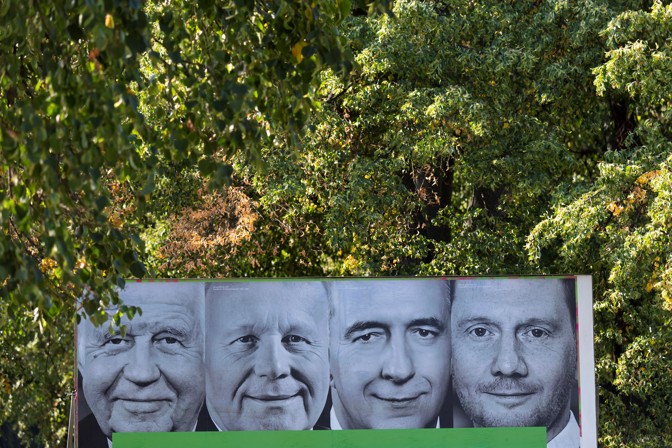

But the emergence of the Greens as an influential player in eastern Germany is an overlooked subplot. In past elections, the party was happy if it scraped over the 5 percent threshold needed to make it into the regional parliament. Now, following a dizzying rise in national polls that has put the Greens nearly level with Merkel’s conservatives, the party is aiming higher. Its new leadership duo, Habeck and Annalena Baerbock, have been hitting the campaign trail with abandon, holding town halls and open-air events in eastern cities that are drawing record crowds.

Read more: [The far right isn’t the only rising force in Germany]

The evening before Habeck spoke here, he held a campaign event in a renovated former gas-storage facility in Zwickau, a city that served as the base of an underground neo-Nazi cell that murdered scores of people with immigrant backgrounds in the early 2000s. Organizers of the Zwickau event had planned for 250 people to show up. Instead, nearly twice that amount came. “You do realize you’re at a Greens event I hope,” Habeck joked as the crowd packed in.

Polls put support for the Greens at roughly 11 percent in Saxony and Thuringia, and at 14 percent in Brandenburg, hardly dominant numbers but roughly double the party’s results five years ago. The AfD, despite its strength, has little hope of governing in any of these three eastern states, because other parties have ruled out forming a coalition with it. The Greens, by contrast, could end up being part of the government in all three regions.

“These are extremely important elections for Germany. Thirty years after reunification, we are debating whether the country will be divided once again,” Habeck told me before his campaign appearance in Zwickau. “If the people here in eastern Germany show they trust us … it will show that our ideas have a much broader appeal.”

Indeed, if the Greens, who have traditionally drawn support from well-to-do, left-leaning urban voters, can lure people in less affluent, rural states, it will prove that concerns about climate change, fueled by record summer temperatures across Europe, are spreading to new corners of the electorate, with potentially far-reaching implications for the political landscape in Germany and beyond.

The rise of the Greens—and of the AfD—is also a story about the decline of Germany’s Volksparteien, the centrist parties that have dominated politics since World War II and that now rule together in Merkel’s listless “grand coalition” in Berlin. Disastrous results for the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) next month could trigger a collapse of her coalition, some analysts believe, forcing early national elections that would end Merkel’s 14-year reign and likely vault the Greens back into the federal government, where they ruled once before, as the junior partner of the SPD from 1998 to 2005.

Read more: [The slow death of Europe’s traditional center]

Habeck, a writer turned politician who has wrapped his party’s climate-first agenda in a feel-good narrative of economic renewal, could then become Germany’s next chancellor.

“Habeck is a friendly new face. People like what he says,” Frank Decker, a political scientist at the University of Bonn, told me. “And Merkel won’t be running again. That is a game changer.”

In their early years, the Greens saw themselves as more of a grassroots movement than a party. When they made it into the federal Parliament for the first time, in 1983, three years after their founding, freshly minted Green lawmakers showed up in the Bundestag dressed in jeans, sneakers, and colorful hand-knit sweaters—an image that captured Germany’s shifting political landscape and that remains embedded in the country’s collective memory to this day.

Back then, the Greens were intent on removing U.S. cruise missiles from West German soil, putting an end to nuclear power, and stopping deforestation and acid rain. When the Berlin Wall collapsed, they badly misjudged the national mood. (Their slogan in the 1990 election was “Everyone is talking about Germany. We’re talking about the weather.”) For the establishment parties, and much of the electorate, particularly in eastern Germany, they were scary, tree-hugging peaceniks.

Within two decades, however, they had entered the mainstream and were sharing power in Bonn (and later Berlin) with Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s Social Democrats. Joschka Fischer, their longtime leader, became foreign minister and, in a sign of the party’s evolving realism, persuaded his colleagues to back the deployment of German troops to the Balkans, the country’s first foreign military mission since World War II.

When Fischer retreated from politics after Schröder’s loss to Merkel in 2005, long-simmering tensions between the party’s pragmatist Realo and more radical Fundi wings broke out into the open. A low point was the federal election campaign of 2013. Thanks to their opposition to nuclear power, the Greens seemed poised to benefit from the Fukushima disaster in Japan two years earlier. Instead they floundered, ridiculed for their plan to force school cafeterias to introduce a “Veggie Day” and haunted by their history of loose sexual morals in the 1970s, after excerpts from a book came to light in which the veteran Green politician Daniel Cohn-Bendit spoke of his sexual interactions with children.

Those troubles seem distant now. Habeck and the 38-year-old Baerbock, elected co-leaders in early 2018, have turned a party once known for its infighting into a model of decorum. Senior members of the party say the two get along well and complement each other: Habeck focuses on the big picture, while Baerbock takes care of the details, holding the party together.

The Greens won just over 20 percent of the vote in elections for the European Parliament in May, trailing only Merkel’s conservatives and winning more votes than any other party in Germany’s biggest cities, from Berlin and Cologne to Frankfurt, Hamburg, Munich, and Stuttgart. In the east, there have also been encouraging signs. Since the start of this year, party officials told me, membership has surged 27 percent in Saxony, 26 percent in Brandenburg, and 22 percent in Thuringia.

Read more: [Fighting the far-right and neo-Nazi resurgence]

One in four voters in these states may end up voting for the AfD. But for the three in four who don’t, there is rising interest in the Greens, particularly among women and young voters who are disappointed with Merkel’s conservatives and their flirtations with the far-right, Katja Meier, a co-leader of the Greens in Saxony, told me. Kai Friedrich, a local Greens activist, says anxiety about climate change is a growing issue in eastern Germany because forests are dying and water levels in the Elbe River are sinking.

Still, the argument the Greens are making on the campaign trail in eastern Germany is not an easy one. They want to accelerate the closure of Germany’s polluting brown-coal-power plants, four of which sit in the Lausitz region, near the border between Saxony and Brandenburg; and introduce a fuel tax to dissuade people from driving cars. They talk about the benefits of immigration in what is perhaps the most xenophobic corner of Germany.

“The traditional message—‘Vote for us and everything will get better’—doesn’t work any longer,” Habeck told me. “Our society and the global landscape are changing so rapidly that people feel these promises are empty. We are telling people that we won’t ignore them or try to return to a past that no longer exists, but rather shape the immense changes that we are facing.”

Volker Ratzmann, a leading Green from the southern state of Baden-Württemberg, told me that it is incumbent on a rich country like Germany to show others what is possible in fighting climate change.

At his campaign events, Habeck frames the elections as a choice between optimism and resignation: Voters can choose a bright future of cleaner new technologies coupled with some short-term pain, or double down on old, increasingly obsolete solutions that lead nowhere.

To fight populism, Habeck said, politicians need to tell a compelling story that arouses emotion and inspires, something Merkel is often criticized for failing to do. He spoke glowingly with me of the enthusiasm and energy he experienced during a week-long trip to Washington, D.C., shortly after Barack Obama’s inauguration.

The son of pharmacists, Habeck grew up in Schleswig-Holstein, on the Danish border. For years, he wrote books with his wife, with whom he has four sons. Only in his late 30s did he become a full-time politician, taking over the leadership of the Greens in his home state and later becoming agriculture minister there. Since taking over the co-leadership of the Greens at the national level, he has become the darling of a German media eager for charismatic new faces. Habeck, with his three-day stubble, open shirts, and bookish intellect, exudes a casual cool that appeals to many Germans after the staid Merkel era and at a time when other countries are turning to brash strongmen.

Still, some critics see more style than substance in Habeck, who uses terms such as radical realism to describe the party’s approach, and who raised eyebrows in June when he described himself as a “secular Christian.” “A lot of people like what he says and how he says it, but they don’t recall afterward what he was talking about,” the German weekly Der Spiegel wrote recently.

And yet the Greens are in the driver’s seat on climate change (Merkel’s government is scrambling to come up with its own plan for the environment after realizing belatedly how important it has become for many voters). But to build on their recent momentum, they will need to do more than impress in the looming regional elections.

Ralf Fücks, an influential early member of the Greens who now runs a progressive think tank in Berlin, says the party needs to get more concrete on a range of topics beyond its signature issue.

“Is there a coherent Green foreign policy? I would say that this is missing,” Fücks told me. “On Russia, on China, on transatlantic relations and the future of NATO, there are lots of question marks but no strategy.”

But here in Chemnitz, where protesters flashed Nazi salutes and chanted “Foreigners out!” one year ago after the death of a German man that they blamed on immigrants, Habeck has other issues on his mind.

“You will be deciding on September 1 what the government in Saxony looks like,” he told the crowd. “But you will also be determining whether Saxony sends out a signal to the world that it wants an open, democratic, optimistic society.”

No comments:

Post a Comment