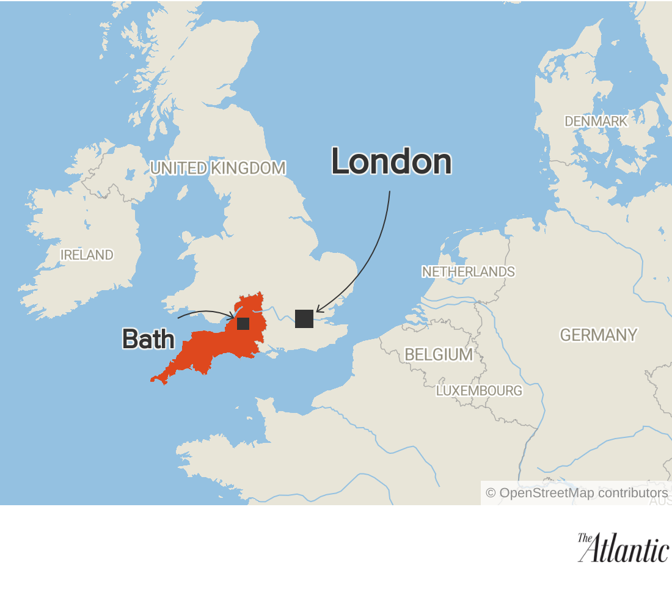

BATH, England—In the run-up to the 2016 referendum on whether Britain should remain in the European Union, people living in England’s South West had more at stake than most. Even though their region benefits from significant EU funds for development, many of them were pro-Brexit. Three years on, as the country votes in elections for the European Parliament, the EU’s legislative chamber, little has changed.

In some ways, this area serves as a microcosm for the way Brexit has been approached across Britain. The focus has been on colorful figures and their hyperbolic rhetoric rather than the mechanism by which Britain will exit the EU, or indeed what the costs and benefits will be.

The South West conjures picture-postcard images—its sandy beaches and bucolic countryside make it a playground for well-heeled vacationers. The reality can be different. Particularly at its extremities, the region contains pockets of serious poverty. Public services are sometimes inadequate. Many people feel isolated and overlooked by the national government in London.

Since 2014, the South West has received more of the EU’s “structural funds,” money earmarked for poorer regions neglected by their home governments, than any other part of England. The funds have improved roads and rail lines in the area, allowed colleges and businesses to expand, and in some places, made the internet faster. After Brexit, it is unclear how the region will make up for this funding shortfall.

[Read: Britons can’t help but make the European elections all about Brexit]

I was born and raised in Plymouth, a moderately big city deep in the South West that has received sizable European investment. During the 2016 Brexit referendum, I was the area organizer on the campaign to keep Britain in Europe. The local financial benefits of membership were a key reason I signed on, and I often tried to steer my conversations with voters toward the issue. Most people I spoke with, however, preferred to discuss (or vent about) national themes, such as immigration, national sovereignty, and the economy. Pundits, who mostly expected the national vote to go the other way, often ignored parts of the country such as the South West ahead of the referendum. In the end, 51.9 percent of British voters opted to leave the EU. In the South West region, that figure was higher. In Plymouth, it was nearly 60 percent.

Unlike in 2016, the South West has attracted national attention ahead of these European Parliament elections. It has done so, however, as a theater for party-political melodrama, not for what’s likely to happen to the region once Brexit happens and EU investment goes away.

A zany roster of high-profile candidates is running in the region. Rachel Johnson, the pro-Europe sister of Boris Johnson, is one of them. Another is Carl Benjamin, a YouTuber known as “Sargon of Akkad” whose comment that he “wouldn’t even rape” a female lawmaker sparked national outrage. Other candidates include Andrew Adonis, a Labour member of the House of Lords whose incessant advocacy for a second Brexit vote was likened to the bubonic plague by a BBC anchor, and Ann Widdecombe, a former Conservative heavyweight now standing for the Brexit Party, a new hard-line anti-Europe group. These days, Widdecombe is better known as a reality-TV star following turns on the British versions of Dancing With the Stars and Celebrity Big Brother. Another competitor on the latter show? Rachel Johnson.

Last week, I attended rallies for Benjamin and Johnson. Benjamin, who is running for the pro-Brexit UK Independence Party, stood on a makeshift sidewalk stage in Exeter, a liberal college town, and goaded protesters to debate with him, mostly on non-Brexit topics such as political correctness and feminism. At one point, a protester threw a milkshake at Milo Yiannopoulos, who had turned up to support him. Johnson’s event, in Bath, another liberal town, was much slicker; she’s running for Change UK, a new pro-Europe party formed by centrist political insiders who left the Conservative and Labour parties over their ambivalent Brexit policies. At neither event, however, did I hear much talk of South West–specific issues related to Brexit.

[Read: The far right wants to gut the EU, not kill it]

The race, in short, has become something of a circus. “I welcome anything that brings attention to our region,” Clare Moody, who currently represents the South West as a Labour member of the European Parliament, told me. “The problem I have about it is that it means the media are again reporting on personalities, and not on substance, and not on our region.”

Moody is one of only three South West MEPs elected in 2014 to be standing for reelection. Three others not only aren’t running again, but are no longer members of the parties they were elected to represent. One of them, Julie Girling, a vocal pro-European, was suspended by the Conservatives for defying the party line on Brexit. She was later expelled. (MEPs are elected through a system of proportional representation, meaning each constituency has more than one representative.)

Girling told me she feels that the celebrity-laden race in the South West trivializes the work MEPs do on behalf of the region. She doubts that any of the high-profile candidates would put in the necessary hard work if elected, though of all of them, she thinks only Widdecombe is likely to win. “The idea of having her as my MEP makes my skin crawl,” Girling said. “She’ll just make us more of a laughing stock as she struts about.”

This week’s elections are likely to be dominated by the state of Brexit nationally, partly because the issues that loomed over the first Brexit vote, including immigration and sovereignty, remain relevant for most voters. These elections weren’t supposed to happen at all—we were supposed to have Brexited by now—but politicians failed to agree on exit terms in time, and so the vote must go ahead. (Although, as Yasmeen Serhan wrote in The Atlantic, no one knows how long newly elected British MEPs will take their seats. It could be weeks, months, years—or possibly not at all.) Unsurprisingly, it’s shaping up to be a proxy battle over Brexit itself. Voters will put their cross next to their preferred party’s list of candidates. The implicit, underlying question, however, is whether we should cut a deal with Europe, leave without one, or call the whole thing off.

The national focus is understandable. But it speaks to a key, ongoing flaw in Britain’s drawn-out efforts to leave the EU: Three years later, the discussion is dominated by personalities, party factionalism, and—this past week—the ethics of throwing milkshakes at right-wing politicians, rather than the potential impact of Brexit.

[Read: Why protesters keep hurling milkshakes at British politicians]

The European Parliament might lack the power of other branches of the EU apparatus, but its MEPs nonetheless have important input on key issues facing Britain. In the South West, its oversight of the farming and fishing industries is particularly central. In 2016, many in these sectors supported leaving the EU, citing excessive bureaucracy. Moody and Girling acknowledged problems with European regulation mechanisms in these areas. Nonetheless, they said, the EU is working to help both sectors, and remains an important market for the export of South West meat and fish.

For some here, the EU funding remains the most important issue. The South West’s disproportionately high share of that funding is due, in no small part, to Cornwall, on England’s southernmost tip. Cornwall is the poorest area in the South West and the only English region currently classified as economically “less developed” by European policy makers. (Parts of Wales also fit that bracket.) Nonetheless, in the 2016 referendum, 56.5 percent of Cornwall voters chose Brexit.

The British government has said it will replace the regional funding lost to Brexit, but so far it hasn’t outlined many specifics. In fact, earlier this year, when the government announced a new regional development fund, the South West got the second-lowest allocation among the eight regions listed.

Girling told me she frequently asked the British government for more details on South West funding after Brexit. “I gave up because it wasn’t getting anywhere. All you get told is bland assurances: ‘Don’t worry, it’ll be fine,’” she said. Parts of the country that currently rely on European money, she added, are “just going to suffer. It’s as simple as that.”

No comments:

Post a Comment