BARCELONA—As Manuel Valls walked through La Sagrada Família, the Antoni Gaudí basilica, French tourists would every so often look with a start and point his way. Trailed by one of his security guards, Valls listened impassively as a guide explained the challenges to the over-the-top building project—sandcastle on the outside, sci-fi columns on the inside—which has been ongoing for more than a century and remains unfinished.

“C’est Manuel Valls,” one tourist said. Oui, it was Manuel Valls, the former prime minister of France. Sí, it is Manuel Valls, a candidate for mayor of Barcelona.

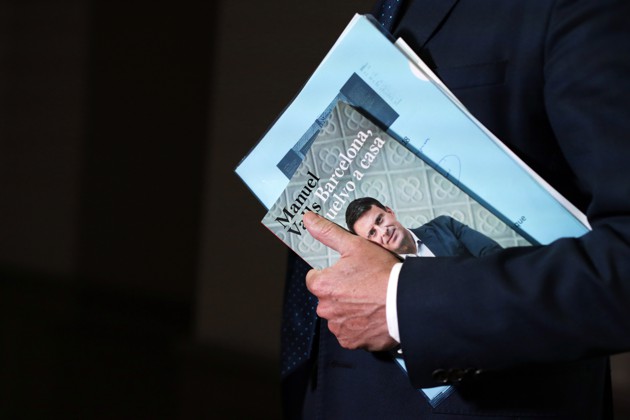

On the face of it, Valls’s latest political adventure is revolutionary. A French career politician who served as prime minister from 2014 to 2016—years marked by terrorist attacks that Valls controversially called acts of “war”—is now running to be mayor of another country’s city, where he was born but hasn’t lived since infancy.

His candidacy is a grand gesture—one that represents the ideal of the European Union, of late so beleaguered, as a space where national borders and identities can dissolve into a glorious, larger transnational project. In practice, Valls’s campaign is a living example, even a cautionary tale, of how all politics is local, and of how that European ideal can be a vague and elusive abstraction in the rough-and-tumble of an election.

That much is immediately clear the minute Valls speaks about his candidacy. Valls is a dual French-Spanish citizen and a fluent speaker of Catalan and Spanish. When I asked him why he wanted to run for mayor of Barcelona in the first place, he began with a long windup. “I’m very attached to nations, to nation states,” he told me, speaking in French as we sat on a sunny morning in his campaign headquarters on Passeig de Gràcia, one of the most elegant avenues in Barcelona.

“Europe,” he continued, is a “very beautiful alliance between democracy, liberty, and the market economy,” and its social-welfare state distinguishes itself from North America. It upholds a respect for the rule of law, and an independent judiciary. It is, he said, “a space of civilization,” and one that “we must, above all, defend.”

It was just after 10 a.m. Barcelona had roused itself and was headed to work. And Valls, the consummate French politician, refreshed by a morning workout, was already making speeches, as if unspooling white papers from his brain. He studied history at the Sorbonne before dedicating himself fully to the French Socialist Party, and tends toward the lofty rhetoric that defines French political life but that feels out of place in Spain, where political discourse and most human interaction tend to be far more direct. After a detour through the differences between the United States and the EU, an entity of “intergovernmental actions,” as he put it, Valls alighted on the answer—or one of the answers—to my original question: Why did he decide to leave France, move to Barcelona, and run for mayor?

“I think it’s a beautiful way of telling the story of Europe, which today lacks a heart, a soul,” he said. “Europe is the euro, it’s trade, it’s the economy, it’s the economic crisis. But how to talk about Europe and how to embody it? How to give it a soul, and feelings? So that’s why I came to Barcelona. I was following the path of a European.”

The path of a European. It’s a noble idea. Upon further inspection, though, it also looks a lot like the path of man who needs a fresh start after a significant political defeat. Or the path of an outsider into a city with its own unique identity. Or, quite simply, the path of a Frenchman into Spain.

Valls was born in Barcelona. His father, a painter who went into exile under Franco, was Catalan. His mother, a retired teacher, is Swiss-Italian. He was raised in France, with occasional visits to Barcelona. (His sister, Giovanna, an author who has written about her struggles with drug addiction, has lived here for years.)

He joined France’s Socialists, the party of François Mitterrand and, later, François Hollande, as a youth and rose through their ranks, eventually becoming mayor of Évry, a suburb of Paris, in 2001, and later winning election to the country’s National Assembly. Hollande made him his interior minister in 2012, before promoting him to prime minister (a move largely seen as an effort to neutralize him as a rival).

Then came the decisive moment of Valls’s political life, the terrorist attacks of 2015. In January of that year, terrorists killed 12 people at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and four more at a kosher supermarket; then in November, militants killed 130 others in coordinated attacks at the Bataclan concert hall, cafés, and the main Paris sports stadium. After the January assaults, Valls gave an impassioned speech in the National Assembly, in which he said that anti-Semitism had no place in France, that its “reawakening” was “the symptom of a crisis of democracy.” France was “at war against terrorism, jihadism and Islamic radicalism,” he said then, a message he reiterated later that year when he called the November 13 attacks “an act of war.” These statements won him admiration from much of France’s Jewish community, the largest in Europe, but further alienated him from its Muslim community, also the largest in Europe, as well as from the base of the Socialist Party.

That would mark the beginning of the end of Valls’s political career in France. He stepped down as prime minister at the end of 2016 to run in the Socialist presidential primaries, which he lost to the more left-leaning Benoît Hamon. That was just ahead of national elections that saw the implosion of the Socialists and the victory of Emmanuel Macron and his En Marche party. Valls quit the Socialists to join En Marche, narrowly winning a contested election to the National Assembly only for Macron to spurn his advances.

[Read: What the November 13 attacks taught Paris]

By then, Valls was one of the most disliked politicians in France. Socialist voters felt betrayed not only by his joining En Marche, but also by the policies he had championed while in power: market-friendly labor reforms that didn’t go over well with the party’s left-wing base, and his stance in what could loosely be called identity debates, such as his efforts to strip French jihadists of their citizenship, a proposal the Socialists ultimately withdrew for lack of support. Valls was essentially seen as a neo-conservative.

The season of terrorism also affected him not just politically, but personally. “It completely upended my life, which also explains my desire for change—for personal change in my private life,” he said. Last year, Valls and his wife, Anne Gravoin, separated, and he moved to Barcelona for a fresh start.

In 2017, as Valls’s political career in France was ending, Catalonia held a referendum on independence and decided to leave Spain, but Spanish authorities deemed the vote illegal. In proceedings that are live-streamed eight hours a day on Catalan television and radio, the referendum’s organizers are now standing trial on charges including disobedience, rebellion, and misuse of public funds.

At the height of the independence push, when Valls was still an elected official in France, he made impassioned speeches in favor of Spanish unity, saying that “unmaking Spain is unmaking Europe,” and in this moment, the germ of his candidacy first sprouted. Valls has repeatedly said, including to me, that he’s a republican in France, which replaced its monarch in the French Revolution, and a royalist in Spain, where he sees the royal family as defenders of Spanish democracy. Opposition to the Catalan independence movement is a pillar of his mayoral campaign. One of Valls’s opponents in the race is an independista running his campaign from jail, adding an element of romantic martyrdom to the political drama.

I asked Valls if he saw himself as Catalan, Spanish, or French. “We all have multiple identities,” he told me. “I feel and have always felt very French.” Here he began to expound on the American and French Revolutions, after which patriotism and the nation became “positive ideas, progressive ideas.” Then, he went on.

“I feel Barcelonian because I think one always identifies with a city. I feel Catalan because Barcelona is Catalonia—it’s a language, it’s a culture, it’s a way of being Spanish.” But he didn’t exactly say he felt Spanish. “I have dual nationality. I have always loved Spain a lot. My father was very Catalan, very Catalanist, and raised us with a love of Spain.”

The Barcelona mayoral race might be the only political contest in Catalonia, though, that doesn’t actually revolve around the independence movement. It will likely be decided on municipal issues—how to regulate Airbnb and digital nomads who are flocking to Barcelona and driving up the price of rent in a city with a dearth of public housing, where the average annual salary is just under 30,000 euros, or $33,600. Locals complain of the blight of narcopisos, squats where people go to buy and consume drugs, an issue that has cropped up in recent years in apartments left vacant after corporations bought buildings and evicted tenants but not yet converted into more expensive rentals.

Valls is one of at least half a dozen candidates vying to depose the incumbent, Ada Colau, a popular mayor with a background in tenants’-rights activism who has been weakened by the city’s difficulties contending with quality-of-life issues, including the cost of rent and the narcopisos.

After Valls’s visit to La Sagrada Família the day I met him, he blasted Colau for her “tourismphobia.” He said vast numbers of people in Barcelona make a living on visitors, and criticized her for calling cruise-ship tourism a plague. When he took questions from the press, one journalist asked what Valls plans to do for the people who live in apartment buildings next to La Sagrada Familia that are slated for demolition to build a larger entrance to the basilica.

We were far from the ideals of Europe, but very much in the thick of issues facing every major European tourist city.

Here in Barcelona, Valls is seen as a curiosity, an ambitious former French Socialist—known in France for his staunch defense of laïcité, France’s sacred belief that religion should be excluded from public life, and a ban on “burkinis”—running on a law-and-order platform in a laid-back, progressive city.

Barcelonians don’t seem to resent Valls for being an opportunist or a carpetbagger. The city has a pretty open heart for welcoming newcomers from all over the world, to say nothing of Catalans such as Valls. But it isn’t so keen on the fact that he lived here for only a matter of months before announcing his intention to run in September. That he keeps making gaffes doesn’t help. Valls got some flak after a television interview in which he admitted that he didn’t know how much a metro ticket cost here.

His style hasn’t gone over well, either. “He campaigned with a bit of arrogance, since he had been a prime minister, and people don’t like that,” Lola García, the deputy editor of La Vanguardia, a conservative Barcelona daily newspaper, told me. “He’s very well educated, much more than local politicians, but at the same time, he doesn’t connect with people.” And Barcelona’s business community doesn’t seem terribly enthusiastic. Why? “Because he’s not from here, and he’s not going to win,” Marta Angerri, the head of Cercle d’Economia, a think tank and business association, told me.

The latest polls place him in the middle of the pack, and whoever wins will likely need to form a coalition, though campaigning won’t formally begin until 15 days before the May 26 election.

At the outset, Valls might have been a candidate with broad, cross-party appeal to voters opposed to the independence movement who still have a strong Catalan identity. But just before he formally announced, Valls was endorsed by Ciudadanos, a liberal, anti-Catalan-independence party that since their endorsement of Valls has drifted rightward. Its association with Valls has put off what might have been natural allies, such as the Catalan Socialist Party and the center-right People’s Party. And that was even before Ciudadanos made a power-sharing deal in Andalusia with not just the People’s Party, but also Vox, a far-right party, after regional elections there in December ended nearly 40 years of Socialist Party rule.

“He wanted to be the candidate of more people,” Antoni Fernández Teixidó, the head of Lliures, a tiny, new center-right business-friendly party that’s supporting Valls, told me of Valls’s candidacy. But that hasn’t happened. “The shadow of Ciudadanos is huge,” he added.

[Read: Spain’s fresh memories of dictatorship]

Then, in mid-February, the Socialist government of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez collapsed—in part over the “Catalan question”—and new national elections will be held on April 28, a month before the Barcelona mayoral election. What happens if after those polls, Ciudadanos decides to ally with Vox in the national Parliament? Valls has been vehement in his critique of Vox, and told me that Ciudadanos would be misguided in making any alliances with the party. But he nevertheless attended a nationalist rally in Madrid in February at which Vox was also present. Valls later told me via a spokesman that he went to the rally “to defend the unity of Spain.” It would, he continued, “be absurd to relinquish patriotism and the colors of the flag to national populism.” He added that he was “a staunch supporter of patriotism, which is the love of ones own, against nationalism, which is the hatred of others.” He said the far-right considered him an enemy in both France and in Spain, and insisted he would “fight the far right with all my strength.”

Valls seemed aware that he’s in a bind. “Ciudadanos is supporting me; I’m not supporting them,” he told me, insisting that Ciudadanos is a “liberal, progressive, and European party.” That’s true. And yet at the same time, under its ambitious leader, Albert Rivera, it’s been more than flirting with Vox. The morning I met Valls, El País published a story about how Vox has put forward a candidate for a provincial election who has written a book denying the Holocaust. When I mentioned this to Valls, he hadn’t known and seemed taken aback.

It would be a great irony if a man known in France for his stance against anti-Semitism winds up two degrees of separation from a Holocaust denier in Spain. The more I spoke with him, the more I began to think that Valls is a man with two countries, three languages, and no political home.

Beyond the civic issues that will decide the mayoral race, Valls and his candidacy are a provocation, the start of a number of conversations about identity—personal, political, cultural, linguistic, European, national, regional, urban—and about the evolution, which is to say the decline, of the center-left Socialist tradition in which Valls came of age.

That political space has been occupied in France by Macron and his party. Valls told me that he might have wanted to break away from the Socialists, but that he didn’t have the nerve to do so in a season of terrorist attacks. Macron had better timing. And the center-left has been overtaken in Spain by new forces on both the right and the left. Spain is one of many populist political laboratories in Europe today. What sets it apart from some of the others—Italy, France, Poland—is the role of the housing market in an economic collapse that has redrawn the country’s political map, as well as the fact that the Catalan independence movement is seen as a kind of progressive force: utopian and perhaps naive, but a left-wing populism, unlike, say, the right-wing nativism of Italy’s League party or Poland’s governing Law and Justice Party.

By running in Barcelona, Valls wants to embody what being a European means, but he might instead represent the crisis of the European center-left. In Valls’s view, the left has been more comfortable in the opposition than in power, and has fractured across Europe over how to handle terrorism and the rise of Islamic radicalism. In France as in Britain, anti-Semitism has become a key issue dividing the left. Valls knows that his stance on the issue, and his comments following the 2015 attacks, were part of his undoing in the Socialist Party. Meanwhile, his electorate in Évry, outside Paris, feels like he’s abandoned it to move to greener pastures in Barcelona.

Not long after meeting Valls, I went for a drink with Maruja Torres, a chronicler of Spain’s transition to democracy and one of the first women of her generation to become a war correspondent. At 76, she’s now a novelist and sometime columnist. “Ah, Valls, he is interesting,” Torres said over a vermouth. She is an unsparing student of power. Her curly hair was magenta and she had a fierce glint in her eyes when she smiled. “The Shakespearean question is interesting. Is he aware of his own failures?”

I told Torres that I think Valls is, or that he is at least aware that he’s missed the moment—in France, where Macron captured it, and in Barcelona, where he’s one voice in a crowded and confusing field—but that he is a born politician who doesn’t know how to be anything else, that he will keep fighting because he is hardwired to do so, whether or not he succeeds. Besides, the political crosscurrents shift quickly in Spain and in Europe these days, and he might well find a new tailwind, if not here, then maybe in Madrid or Brussels, depending on what happens in the Spanish national elections and the European parliamentary polls, which are the same day as the Barcelona mayoral election.

When I asked Valls what he hopes his political legacy will be, he said his was “a European fight.”

“It’s not my fate that’s at stake,” Valls said. “I’ve already done a lot, and if I don’t win, I don’t win.” He said he plans to stay in Barcelona no matter what happens in the race, for personal reasons. His new paramour is Susana Gallardo, who comes from a pharmaceutical fortune and whose ex-husband reportedly sold Pronovias, a wedding-dress company, for 550 million euros in 2017. Valls and Gallardo have become regulars in Spanish tabloids, and even in Paris Match, which Valls sued last summer after it published photos of the couple relaxing on a Spanish beach.

Then, for a second, he seemed to catch himself sounding a bit defeatist. “I’d like to win because it’s more personal, because it would be a way of showing what Europe is,” he said. “That’s something that’s never been done before.” Never before, and probably not yet.

No comments:

Post a Comment