The depths-of-winter holiday season always seems to bring more than its share of prominent deaths. Two I particularly noted and mourned these past few weeks, and that recent news makes more relevant, were of the writers Ward Just, on December 19, and Bill Greider, on Christmas Day.

The two men had established very different reputations by the end of their lives: Ward Just in the literary world, as author of more than a dozen novels plus numerous short stories; Bill Greider as author of trenchant books and magazine articles about politics, finance, economic justice, and inequality. Just spent most of the past few decades living and writing in New England or in Europe; Greider lived through most of his working career in Washington. In personality, Bill Greider had the sunnier disposition (as the writer Jim Lardner, who worked with Bill at The Washington Post, recalls in a lovely appreciation). If Ward Just were portraying himself in one of his stories, he might have applied terms like crusty or gruff (before getting to generous and kind.)

But I had long thought of them as a pair. Both were born in the mid-1930s, in the Midwest: Ward Just in the fall of 1935, in Indiana, to a newspapering family; Bill Greider the following summer, in Cincinnati, where his father was a chemist and his mother a schoolteacher. Though neither had any trace of the “academic” in his bearing, both had brushes with fancy education. Just went to the private Cranbook school in Detroit and then started but did not finish at Trinity College. Bill Greider graduated from Princeton before heading into newspapering. “The Princeton thing came as a bit of a shock to me,” Jim Lardner pointed out in his tribute, even after knowing and working with Greider for decades. “I had Bill pegged as the product of a mining or milling family.”

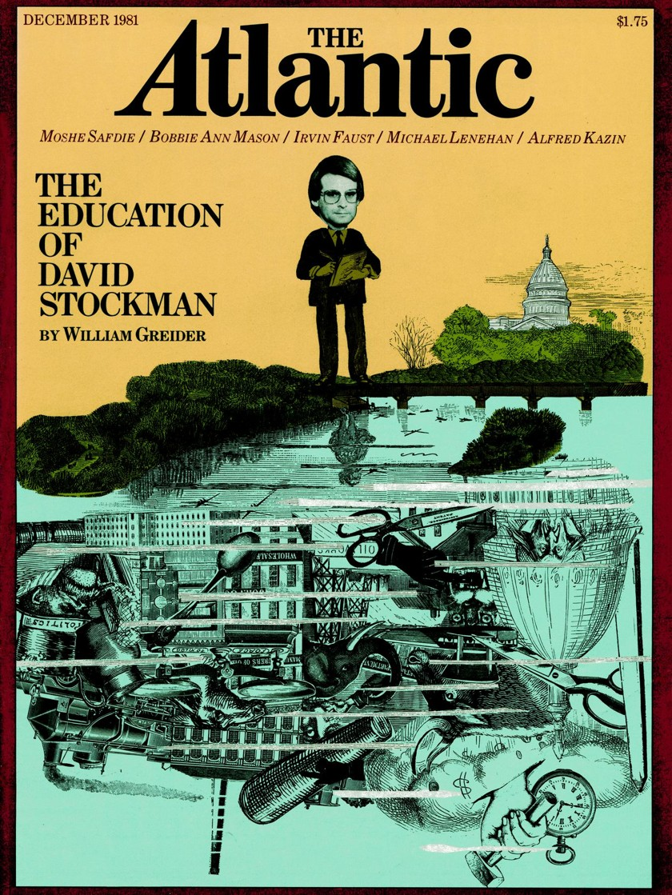

Both men had episodic but significant connections with The Atlantic. For Greider, this was mainly through his hugely influential 1981 cover story, “The Education of David Stockman,” which revealed the hollowness of the new Reagan administration’s claim that it cared about reining in federal spending or reducing deficits. (All it actually cared about, as the story laid out with incredible-but-true damning inside detail, was cutting taxes.)

For Ward Just, the magazine was home for some of his reports about the U.S. debacle in Vietnam, and the predicament of the post–Vietnam War military. When I was writing my own Atlantic pieces about the military in the early 1980s, which became the book National Defense, I carefully reread, and tried to learn from and aspire to, the multi-month reporting project Just did a decade earlier for The Atlantic. This was a cover story called “Soldiers,” which won the National Magazine Award and became the basis for Just’s book Military Men. Among its passages that have stayed with me, and that grew from Just’s bona fides as a combat reporter in Vietnam, is one in which he is talking with an officer about “dumb” soldiers in that war, “those with IQs of 80, the ones called Shitkick and Fuckhead, the clumsy ones”:

“Well what the hell, you have got to have those guys who will go out there when no one else will,” a major at Leavenworth told me and when I didn’t say anything but just sat looking at him he colored and half apologized and said that he didn’t mean it quite the way it sounded. But he did.

In those days, no one knew what was going to be inside a magazine—Harper’s, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, the nascent Rolling Stone—until a fresh issue showed up in the mail or at a newsstand. In a way almost impossible to imagine now, those fresh-issue debuts were big events. Half a century later, I can remember spotting Ward Just’s “Soldiers” issue of The Atlantic at a terminal newsstand on my way out of the country to start graduate school. A few months after that, an issue of Harper’s that featured David Halberstam’s “The Programming of Robert McNamara” (later part of his renowned The Best and the Brightest) arrived as the cover story of a sea-mail copy of Harper’s. I stood in the college courtyard and read it page by page.

No doubt the strongest link between Just and Greider is that both were reporters and writers for The Washington Post, during a golden age of reporting and writing there, under the editor and impresario Ben Bradlee. Ward Just came to the Post from Newsweek around age 30, and was dispatched to Vietnam—where he was wounded in a grenade attack a year later, in 1966. Greider came from the Louisville Courier-Journal in 1968, in his early 30s, and stayed at the Post as a reporter and editor for nearly 15 years. At certain moments, certain institutions have lasting influence, and Bradlee’s Post in those days, before and after its central role in Watergate, was such a place.

I was half a generation younger, just starting in journalism in the early 1970s, in my early 20s, and there were no two people whose work I studied or respected more than Ward Just and Bill Greider. Some of the reasons were evident then; others I have come to appreciate all the more in retrospect. Both men set examples in how to portray public life through their writing, and in living a life of principle as well.

By his mid-30s, and no doubt hastened by his physical and emotional ordeal in Vietnam, Ward Just had begun to shift from newspapers to writing novels and short stories. Not all of his fiction concerned politics or public affairs, but his work in that field was revolutionary at the time. In 1973, he published a collection of short stories called The Congressman Who Loved Flaubert and Other Washington Stories. At the time I was starting my first magazine job, at the Washington Monthly. The impact of Just’s work was such that I wrote an article about its implications, called “Will Editors Ever Love Flaubert?”

In those days the three main conventions of political writing were: (1) the straight “Congressman X said today” dispatch, which these days we might call the C-SPAN approach; (2) fantastical roman à clef fictionalized accounts, which back then meant novels like Seven Days in May or Advise and Consent, and these days might mean a series like House of Cards; or (3) the omniscient-toned “informed sources say” D.C.-based column, a staple over the years. The journalism of the very early Watergate era had not yet developed what a decade later had become a cliché: the snarkily “observational” profile or column. “Candidate X looked exhausted. Over eggs and sausage at the Holiday Inn Des Moines, he glanced wearily at his aides and obviously wished he were anyplace else.”

In his stories, Ward Just applied a fully novelistic (rather than satirical or polemical) sensibility to public figures. With allowances for the hyper-certainty of someone fresh out of graduate school, here is what I noticed about Ward Just, at the start of his career in fiction. (The reference to “Reedy” in this passage is to George Reedy, a press secretary for Lyndon Johnson who had recently published a book called Twilight of the Presidency—and “Frankel” is Max Frankel, at the time a hugely influential reporter and bureau chief at The New York Times. Sic transit ...)

In one of the two really first-rate stories in the book, “A Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D. C.” (the other is the title story), Just gives us what Reedy attempted to give and what all the journalists like Frankel never put in their stories: a demonstration that he understands the complexity and motivation of human beings in political situations. In his story, a White House aide, facing a change of administrations, is preparing to leave but trying desperately to stay. This is a familiar political situation: Frankel must have written about ones like it, and the political theorists have, too. But Just adds a dimension missing in the other accounts, and in so doing comes much closer to telling the truth about this part of government:

“He remembered the black Mercury sedans, with the telephones and the reading light in the rear seat. He was up every morning at seven sharp, swinging into the big circular lobby at quarter to eight. He remembered the silence of the lobby, and the wan light from hidden lamps. In the early morning there were always one or two visitors seated on couches, nervous men waiting for appointments, who put down their newspapers when they saw him. It was as if they felt newspapers were an unnecessary frivolity, a sacrilege in his presence, something profane... .

“Then, safely inside the sanctum, he’d relax and stroll down the hallway to his office and the morning's business. Before he did anything he checked the appointment book to see what was scheduled. What was public, what private, and what personal. Then he checked the Oval Office to see if the old man was in. To see if there was anything special that day. Anything that needed doing. Anything at all.”

This is not just nice detail; it has as much to do with understanding the way decisions are made in government as anything the political reporters and theoretical analysts can say.

I think (and argued 25 years later in another Washington Monthly piece) that the skills and insights Ward Just brought to his Washington fiction are ones that all public-affairs writers, plus historians and people in general, should develop as well. For more about Ward Just’s accomplishments as a writer and person, see David Stout in ArtDaily.com; the New York Times obituary, also by Stout; a Washington Post obituary by Harrison Smith; and a 1999 profile-interview, by Roger Cohen, in The New York Times. Plus “Why America’s Best Political Novelist Is Required Reading in 2018,” by Susan Zakin, which came out during the Kavanaugh hearings of that year.

The turn Bill Greider made was not from newspapering toward “literature,” as Ward Just had done, but, as Greider himself once put it, from mere “facts,” toward truth. Not long after his Atlantic piece on Stockman, Greider left the Post, where he had been one of Ben Bradlee’s most celebrated protégés, to work for Rolling Stone. There and in subsequent venues he essentially extended the logic of the Stockman piece: namely, about the way economics and politics had become skewed toward the interests of the already powerful, and away from the ordinary households of the United States or the rest of the world.

He wrote a series of influential books, starting with Secrets of the Temple, a best-selling exposé of the Federal Reserve system, in the late 1980s. The titles of some of his other books suggest their themes: One World, Ready or Not: The Manic Logic of Global Capitalism; andThe Soul of Capitalism: Opening Paths to a Moral Economy; and The Trouble With Money: A Prescription for America's Financial Fever; and Who Will Tell the People?: The Betrayal of American Democracy. His message was increasingly hard-edged and cautionary, even as his personal and literary tone remained upbeat and approachable. He was an analyst and a beacon, never a scold. And if you wanted to find one journalist whose work gave a clear-eyed perspective on the “financial-ization,” the inequalities, and the Gilded Age–ism of the American economy of the past generation, you would have a hard time doing better than Bill Greider. His articles, broadcasts, and books will stand up.

It was a sign of Bill Greider’s gregarious and generous personality that his death occasioned so many personal tributes, especially from economically progressive writers. Apart from Jim Lardner’s “Hail and Farewell,” I noted: “On the Death of My Friend and Mentor,” by Mike Elk; “Bill Greider Showed Us What American Journalism Could Be,” by Robert Borosage; “In Memoriam,” by Tony Wikrent; and “A Fearless Tribune of Progressive Journalism Is Gone,” by Jessica Corbett. I’m sure there are more.

The definition of journalism is that it is of the moment. What we put out is our best approximation of the truth, by deadline time. If you didn’t have a deadline, you’d be in another business. It is natural that most of a reporter’s work is writ in water, and most of their names are forgotten when they step aside.

But there are writers we learn from because they have found truths that last beyond the moment. They maintained the long view, while wrestling with the immediate. Ward Just, with his reporter’s eye guiding the spare elegance of his fiction, and William Greider, with his determination to convey truths that might not neatly fit the conventions of regular journalism, are among those whose works and examples will last.

No comments:

Post a Comment