Tucked away in a drab industrial estate on the outskirts of the Swiss town of Spiez lies a multistory concrete office block flanked by a parking lot and a soccer field. A modest gate with a small plaque is all that greets visitors. A river rolls behind the building, fed from the peaks of the Blüemlisalp massif above. This is the Bernese Oberland, the corner of Switzerland where James Bond met Blofeld in a revolving mountaintop hideaway; where Sherlock Holmes plunged to his death.

The building in question, an outpost of Switzerland’s Federal Office for Civil Protection, might be unassuming—home to just 98 academics, engineers, apprentices, and technicians—yet its occupant, the Spiez Laboratory, is world-renowned. The elite facility focuses on global nuclear, chemical, and biological threats, and is one of a limited number of sites designated by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) to conduct research and analysis. Safely under the protective cloak of the country’s diplomatic neutrality, Spiez Laboratory carries out its work with little fanfare or controversy.

Over the course of a few months in 2018, however, this gentle existence was upended, as the lab became caught in a cold war between Russia on one side and the United Kingdom and the West on the other, fought in public and in the shadows, online and in person, occasionally flashing hot in deadly fashion. From the attempted assassination of a double agent in a sleepy English city to the expulsion of scores of Russian diplomats from Western capitals, this fight would grow and morph, drawing in a chemical-weapons attack in Syria and rolling scandals about Russian sports doping.

Through it all, Russia and Britain went toe-to-toe in an international intelligence and PR battle, one in which each landed blows, exposing fissures in their respective systems and societies. Yet, as NATO leaders meet in London this week to discuss the future of the military alliance 70 years after its founding, other lessons emerge, with implications for the wider contest between Russia and the West, which are vying for influence, respect, security, and raw geopolitical power.

Whereas NATO was founded to unite the Western world against the threat of conventional military aggression by the Soviet Union, eventually contributing to the Communist bloc’s demise, the alliance is today confronted with a recalcitrant Russia that seeks to leverage propaganda and disinformation to sow confusion and discontent, and that exhibits a willingness to use its traditional military force and intelligence agencies to expand its influence. It is a Moscow that is able to project disproportionate power—despite being dwarfed in economic size and resources by even mid-tier Western countries—thanks to a web of international influence, aggression, tactical cunning, and criminality.

At the same time, NATO and its members are divided, distracted, and shorn of a coherent strategy to deal with Russia’s efforts. The grouping’s superpower, the United States, is led by a president whose commitment to the alliance’s underlying principle of collective defense is in doubt; its other significant members are consumed by domestic strife (Britain), questioning NATO’s strategic future (France), or lack the military might and political will to fill the gap (Germany). And faced with a new array of threats from Russia, the alliance has more than once been caught unawares, at times thanks to its own unforced errors but also in no small part due to a lack of long-term vision to do anything other than de-escalate tensions. Despite Russia deploying a chemical weapon on the streets of a NATO member (also Britain), the country’s international freeze is already beginning to thaw, its economy is growing, and its leadership, on the face of it at least, remains secure. It has successfully expanded its influence in the Middle East and has secured its illegal land grab in Crimea.

The period from the attempted murder of the former Russian spy Sergei Skripal in March 2018 to a major Western counterblow exposing Moscow’s behavior in October 2018 offers a window not just into these challenges, but also into others that are only just emerging as technological advances change the very nature of information warfare. To understand how the battle played out, I spoke with several current and former officials—government aides, communications advisers, and members of the intelligence services—as well as politicians in London, most of whom would speak only on the condition of anonymity in order to discuss sensitive intelligence matters. I also consulted security, diplomatic, and cyber experts. (The Russian embassy in London declined to respond to a series of detailed questions I sent them, instead referring me to a statement on its website in which Moscow denies any involvement in the poisoning and claims it was an act carried out by the British secret services.)

Unlike a conventional battle, though in keeping with much of modern conflict, there are no obvious measures to determine who won and who lost. The months-long information war that Russia fought with Britain was one in which mistakes were difficult to judge and success hard to immediately quantify.

This is a story about disinformation and spycraft. It is also a story that again and again returns to the tiny Swiss town of Spiez.

The details of the Skripal poisoning are well known: On the night of March 4, 2018, the former Russian spy, who was living in retired exile in Britain, was found alongside his daughter, who was visiting from Russia, foaming at the mouth on a park bench in Salisbury, 90 miles southwest of London.

Eight days later, then-British Prime Minister Theresa May formally accused Russia of carrying out the attack. Britain’s Porton Down military-research facility—which, alongside the Spiez Laboratory, is one of the centers of expertise accredited by the OPCW—had determined that the Skripals were poisoned with a nerve agent called Novichok. The chemical weapon, May told Parliament, had been smuggled into the country by two hitmen working for Russia’s military-intelligence agency, the GRU. In response, Britain and its allies in 28 countries expelled more than 150 suspected Russian spies. Russia protested its innocence and denounced the Western response. (Skripal and his daughter ultimately survived. Another woman, Dawn Sturgess, died, after spraying what she thought was perfume, but was in fact Novichock, onto her wrists, and a police officer was hospitalized while investigating the poisoning of the Skripals.)

Details of the information war that ensued are only now emerging.

By the time May made her allegation in Parliament, a Russian campaign to discredit it was already in full swing. In just the first week after the attempted assassination, according to five British officials who spoke with me, the U.K. government tracked 11 alternative theories about the Skripal poisoning that all originated in Russia. A March 2019 report by King’s College London found that Russian-government funded outlets RT and Sputnik alone were responsible for 138 separate and often contradictory narratives about the Skripal poisoning in the four weeks following the incident. These included claims that the poison came from Porton Down; that the Skripals were never, in fact, poisoned; even that the poisoning was designed to distract from Brexit. Russian media also speculated variously that it was a British plot, an American plot, a Ukrainian plot, or a plot to frame Russia. May told members of Parliament that she had been personally accused of inventing Novichok.

The onslaught of such stories in the weeks and months after the Skripal attack—and their success in reaching a wide and receptive audience—emerges in lists of the most viral social-media content from that period. This data was gathered for The Atlantic by the online monitoring company NewsWhip, which tracks how many “interactions” a particular news story has garnered on social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest—measured by the number of likes, shares or comments it has received. In some cases, there appeared to have been genuine orchestration of these efforts, but other instances show opportunism, with Russia-friendly outlets jumping on apparent contradictions in Britain’s public statements.

Moscow’s goal, according to U.K. officials tasked with monitoring and counteracting the Russian propaganda war, was simply to flood social media with false narratives and information that would cast doubt on the established British and Western positions, not with the goal of offering one particular alternative explanation, but simply to muddy the waters sufficiently to make people question their own government. Russia denies the allegation and accuses the U.K. government itself of manipulating the media with leaks and censorship.

This Russian strategy is wearily familiar to former Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe (as well as the United States, during the 2016 presidential election), officials and experts I spoke with said. And early in the summer of 2018, there were concerning signs for London that it was having some effect. Internal government polling carried out in the months after the poisoning showed that a significant proportion of the population did not believe the British government’s assertion that Russia was behind the attack, according to an official briefed on the data, with the most skeptical being those aged 18 to 24. A September 2018 government memo, shared with The Atlantic, that distilled the results of polling showed that the “perception of Russian culpability” stood at just 55 percent. This was down from a peak of 65 percent at the end of March—the month of the attempted murders. (One of May’s aides told me that this lack of trust in government is now a major structural challenge when dealing with incidents of national security.)

Some of those I spoke with insisted that such setbacks were only temporary, but all largely agreed that Russia reacted quickly and effectively. “There was a private admission that we had lost the information battle,” one senior U.K. government official involved in the British counterattack told me. “We had ceded the ground. The Russians were just really quick off the mark.”

Numerous stories by outlets such as RT and Sputnik promoted dueling theories as to who carried out the Skripal poisoning, but when it comes to sowing confusion, one story stands out, and Spiez was at the center of it.

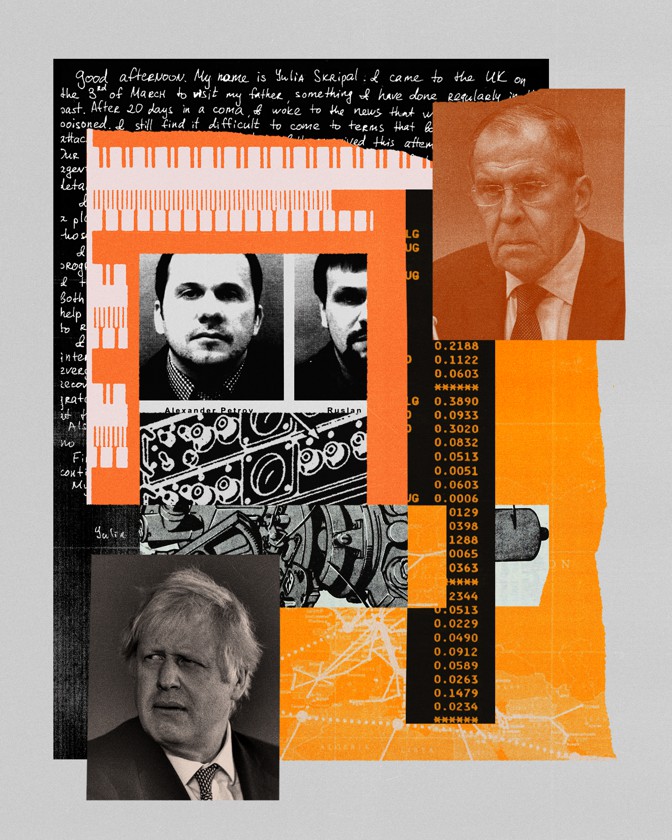

On April 14, 2018, RT published an article that would go on to become the most viral news story in 2018 about the incident as measured by online interactions, NewsWhip data shows. According to RT, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that a “Swiss lab” had discovered that a different toxin was used to poison the Skripals—not Novichock, but BZ, which was, as RT put it, “in service” in the United States, Britain, and other NATO countries.

The report would go on to be shared on social media by RT as well as by accounts such as the WikiLeaks Task Force, which describes itself as the “official @WikiLeaks support account,” verified with a blue checkmark on Twitter. The story would rack up 137,360 social-media engagements, still the most of any story published on the Skripal affair.

And yet the article was entirely misleading. Spiez was indeed one of a small number of international centers chosen by the OPCW to confirm the conclusions reached by Porton Down, and it did find a different toxin from Novichock. But that was part of the process: After receiving samples from the Skripal poisoning from the U.K., the OPCW, following protocol, added a new substance into the batch for quality control—a test, in effect, to ensure that Spiez’s and other laboratories’ results were accurate. If they did not find the added element, then whatever else they found could not be trusted. The toxin added by the OPCW was a derivative of BZ.

It would be surprising if Lavrov was not aware of this distinction. On April 11, the OPCW, of which Russia is a member, confirmed the British findings in a report that named the control substance. Was it a simple misstep on the foreign minister’s part? How did he know that Spiez had done the testing? That the Swiss lab was among those chosen by the OPCW to confirm Porton Down’s conclusions was kept confidential as per the OPCW’s security protocols, a rule seen as “sacrosanct,” according to one of the U.K. officials who spoke with me. Andreas Bucher, a spokesman for Spiez, told me that the research facility did not even know which other sites were used to test the findings. The Russian embassy in London declined to comment on the incident when I asked them about it.

Unsure of how to respond without confirming that it was one of the laboratories chosen by the OPCW, something it was not allowed to do, Spiez initially published a tweet saying that it could not comment on Lavrov’s assertions, and then later released another saying that it had “no doubt Porton Down has identified Novichock.” Lavrov claimed to be quoting from Spiez’s report on its tests, but Bucher said he had falsely cited the report. “We don’t write prose,” he said. “We write formulas.”

The U.K. government itself did not respond to Lavrov’s claims. The Spiez tweet partially correcting the story received only about 1,000 retweets—less than 1 percent of the engagements recorded by the original RT story. Regardless, the claim was out there, being shared across the world, even though the OPCW itself had said that its laboratories had confirmed Britain’s original findings.

If the most viral Skripal-related story illustrates how Moscow’s propaganda machine looked to actively plant disinformation, the second on that list highlights how Russia was able to take advantage of unexpected openings as well.

The Independent, an online British outlet, on April 3 published a story based on an interview given to Sky News by Gary Aitkenhead, Porton Down’s chief executive. Aitkenhead said that the British facility had confirmed that the toxin used in Salisbury was Novichock, but that its scientists “have not identified the precise source” of where it came from. Just days earlier, though, then–Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson had claimed that Porton Down had confirmed that the nerve agent originated in Russia.

The apparent contradiction exploded into life online, with the Independent story getting picked up and promoted by Kremlin supporters, as well as by the Russian embassy in Skopje, North Macedonia, an RT journalist in North America, and even a Facebook account, “San Diego For Bernie Sanders 2020,” eventually receiving 93,999 interactions on social media, according to NewsWhip, a high figure even for a story that was dominating the news. Britain rushed to repair the damage after a 10 Downing Street rapid-response unit, which monitors web traffic and works closely with the national-security communications team, noticed the story gaining traction online. (One security official told me that government analysis of social media showed that Salisbury-related posts made up 12 percent of the entire U.K. digital conversation on April 3, the second-highest figure during the entire crisis, after the day May blamed Russia for the attack.)

Later that day, Porton Down tried to clarify Aikenhead’s remarks, tweeting that the facility’s “experts have precisely identified the nerve agent as a Novichok. It is not, and has never been, our responsibility to confirm the source of the agent.” Security officials contacted journalists to explain the discrepancy, with calls made to Sky News in particular with a request for a public clarification. A week later, the U.K. released a letter sent from May’s national-security adviser to the secretary-general of NATO, which formally laid out the charges against the Russians.

The episode is seen by those inside Britain’s security communications team as the most serious misstep of the crisis, which for a period caused real concern. U.K. officials told me that, in hindsight, Aikenhead could never have blamed Russia directly, because that was not his job—all he was qualified to do was identify the chemical. Johnson, in going too far, was more damaging. Two years on, he is now prime minister.

The aftermath of the Skripal poisoning illustrated not only a PR offensive waged by outlets sympathetic to Moscow, but also the breadth of the Russian state’s capabilities and efforts to include its diplomatic corps as well as its intelligence agencies.

At the same time the media blitz was taking place, the Russian embassy in London was writing letter after letter to the U.K.’s Foreign Office with scores of detailed questions that British officials argued were designed to tie up their time and attention. From March 6—two days after the Skripal assasination attempt—to February 18, 2019, the embassy fired off dozens of note verbales, or official diplomatic correspondence, with 41 requests and 57 questions. (The Russian embassy has published a list of these demands.) Inside the U.K. government, an official told me, this barrage was referred to as a “diplomatic DDoS attack,” a reference to the cyberstrike in which a server is shut down simply by overwhelming it.

At the same time, a surge in malign Russian bot activity was detected online, in which social-media accounts were activated to amplify and spread messages. In the six weeks following the Skripal poisoning, through to the April 13 air strikes on Syria launched by the U.K., U.S., and France in response to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons, British officials say they calculated a 4,000 percent increase in this type of activity.

The GRU, the same organization that dispatched the two hitmen to Salisbury, also played a role, and, once again, Spiez was at the heart of it.

In May, 2018, OPCW facilities around the world received an email apparently from the Spiez Laboratory inviting them to a conference for specialists in chemical and biological warfare. The conference itself was real, the third such meeting organized by the Swiss research site, and the email was sent in the name of the Swiss Federal Department of Defence, the government agency responsible for the laboratory. Attached was a Word document that purported to contain information about the meeting.

There were, however, small giveaways that all was not right: The shade of red on the Swiss flag in the top left corner of the document was slightly off, and some formatting in the letterhead was wrong (the abbreviation FOCP—for Federal Office for Civil Protection—was used on the wrong line). In fact, the Word document contained malware that would embed itself into any computer that opened the file. But it would take weeks for anyone to notice, and only in July 2018 did Spiez issue a warning on its Twitter account that an email had been sent in its name without its knowledge, one that was actually a sophisticated spear-phishing attack, a cyber Trojan horse known as an advanced persistent threat, in which a computer is accessed by stealthily giving attackers full control of the compromised host’s network.

Who was behind the attack—and what they hoped to achieve—has never been confirmed. The Russian embassy declined to address this specific case when I asked them about it. Kaspersky, a U.S. cybersecurity firm that analyzed the incident, told me that it did not know for certain who the hackers were, whether they had been successful, or even what their goal was. In the shadowy world of spycraft, it’s almost impossible to be sure about what is a false flag and what is real, the company said.

Britain’s National Cyber Security Centre is less circumspect, however, assessing “with high confidence that the GRU was almost certainly responsible.”

Through a special “link door” from 10 Downing Street, deep inside the Cabinet Office in central London, lies the U.K. government’s main emergency-response center: Cabinet Office Briefing Room A—or Cobra. This is the British equivalent of the White House Situation Room. It is where emergency meetings are held at times of crisis, to coordinate strategy in the most secure environment.

Attached to Cobra are a number of boardrooms where officials can listen in to what their ministers are discussing inside. Throughout the spring and summer of last year, a group of some of the most senior government communications officials, dubbed “Comms Cobra,” met daily to discuss how to respond to the Russian disinformation blitz. They were in full crisis mode—not only was the Russian campaign overwhelming in its scope, but Russia seemed to be one step ahead of the U.K. as well.

Among the measures the group took was to tighten the circle of who was in the know. At one point in the summer, the number of people, government departments, and agencies involved in responding to the Salisbury case was huge. The Department for Environment was leading the clean up and the Home Office was dealing with security, while London’s Metropolitan Police, Britain’s intelligence services, and the local police force were investigating. Salisbury’s local council, the Foreign Office, Downing Street, and the Cabinet Office were involved too.

New processes were put in place, raising the level of official secrecy on some communications and resulting in often cumbersome procedures. Instead of having a single phone number for meeting participants to dial in to, for example, the Metropolitan Police—which leads Britain’s national counterterror and security operations—began holding conference calls by dialling each individual separately, one after the other, infuriating officials who were left waiting on the line for half an hour before discussions could start.

On September 5, 2018, Britain finally made its move. May told the House of Commons that the two Russian spies responsible for the Skripal poisoning had been identified, news that, because of the tightened communications, only a select number of cabinet ministers were even aware of. She outlined which flight the pair had arrived on, when and how they visited Salisbury, when they arrived at the Skripals’ house, and which flight they took back to Russia. CCTV footage was released of the two at various stages of their trip. Traces of Novichock were even found in their shared hotel room, May said. Hours earlier, the Metropolitan Police had held a “lock-in” with security journalists to brief them on the findings. (The Russian embassy claims the CCTV recording of the two Russians “only confirm the fact of their visit to Salisbury and do not point at any wrongdoings.”)

The effect of the surprise information barrage was dominance online. Only two of the 10 most viral stories in the weeks following the announcement were sympathetic to Russia, according to NewsWhip. Finally, officials recalled, it felt as though the U.K. was the aggressor. “This was all kept secret to put the Russians on the hop,” one told me. “Their response was all over the place from this point. It was the turning point.”

Amid an apparent failure to counter the British case, the accused hitmen appeared on Russian state media claiming that they had visited Salisbury on a sightseeing trip. Inside the Cabinet Office in Westminster, an official said, Britain’s security communications team sat “glued to the telly” watching their claims but ultimately decided not to react—across Europe, satirical TV shows and websites were picking up the story and making fun of it.

If September was the month Britain wrested control of the Skripal narrative, October was when it rocked Russia with a significant blow of its own, one that was months in the making.

On April 10, a month after the poisoning, four men arrived in the Netherlands on diplomatic passports. Three days earlier, Assad, a key ally of Russia, had launched a chemical-weapons attack on a suburb of Damascus, and the OPCW, which is based in The Hague, was tasked with investigating not only the Skripal poisoning but also the Syrian chemical-weapons attack. The men, all Russian intelligence officers, had been assigned a hacking operation in which they were to target the OPCW’s networks by sneaking in via Wi-Fi connections.

From their arrival, however, the group (subsequently identified as belonging to GRU Unit 26165) was being monitored by the Dutch security services, and on April 13, the four were arrested. Two of them had left their equipment in the trunk of a rental car parked outside the OPCW’s headquarters. For the Dutch, British, American, and Swiss secret services—all of which were involved in the operation—they had obtained a treasure trove.

The abandoned equipment revealed that the GRU unit involved had sent officers around the world to conduct similar cyberattacks. They had been in Malaysia trying to steal information about the investigation into the downed Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, and at a hotel in Lausanne, Switzerland, where a World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) conference was taking place as Russia faced sanctions from the International Olympic Committee. Britain has said that the same GRU unit attempted to compromise Foreign Office and Porton Down computer systems after the Skripal poisoning.

The arrests were not immediately made public, though. On October 4, the U.K. published a list of transgressions by the Russian state and specifically the GRU unit that was caught. That morning, the British ambassador to the Netherlands joined the Dutch defense minister at a press conference in The Hague where they lifted the lid on the attempted Russian hack of the OPCW. In the afternoon, the U.S. Department of Justice announced charges against seven GRU agents linked to the Dutch investigation, accusing them of hacking into WADA and the OPCW, and of cyberattacks aimed at a U.S. nuclear-energy facility. Security officials in London told me that everything was carefully coordinated and timed to coincide with the U.S. indictments. A joint statement from the British and Dutch prime ministers was released to ram home the message. The Russian embassy declined to comment on the operation or the U.S. indictment.

During the week of the OPCW press conference just one of the top 25 most viral stories was from a pro-Russian outlet—and even this was a relatively straightforward piece from RT. “There were some signs that we had landed a blow,” one senior security official told me.

The OPCW was not the only target on the unit’s itinerary on its trip through Europe. According to the U.S. indictment, also in the GRU team’s possession on the day they were arrested were train tickets to Basel, Switzerland. American authorities allege that they would have then traveled onward—to Spiez.

Having been at the forefront of the international PR battle with Russia, the U.K. feels that it is now well placed for any future battles. It has created a national-security communications team based at the heart of government in 10 Downing Street and the adjoining Cabinet Office. Communications strategy is now seen as being part of national-security strategy.

Nina Jankowicz, a fellow at the U.S.-based Wilson Center specializing in disinformation who has advised the Ukrainian government on how to combat the Russian threat, told me that the U.K. effort was “leaps and bounds ahead of what we had seen before.” British officials did a good job of highlighting “all the absurd claims” coming out of Russia, she said. “The fact the U.K. system was able to respond under such stress shows the system was working as it should,” she added, pointing in particular to Britain leading the coordinated expulsion of diplomats. “We’ve not seen anything like it since the Cold War. The U.K. is filling in the leadership gap where the U.S. now cannot—or will not.”

Still, if Britain won a victory, it was tactical, not strategic. Officials say the problem for Western countries is that while Russia might be a relative economic minnow, it has continued to fund its national-security state to superpower levels while NATO has become more and more reliant on the U.S. for its defense since the end of the Cold War. Russia is also aided and abetted by a willingness to ignore international law, norms, and conventions—and the West’s apparent refusal to do the same in return. (Russia’s intervention into British politics remains a live issue, after the U.K. government refused to publish a report into Moscow’s infiltration before Britain’s election this month.)

Even more fundamentally, in the absence of any coordinated Western strategy to forcefully respond to a crisis sparked by limited forms of Russian aggression, Moscow has been able to achieve a significant expansion of its influence. By moving quickly, Russia changed the rules of the game on the ground before the West could react. Whether in Syria, Crimea, or elsewhere, Russia has filled a vacuum left by American withdrawal or indecision—in some cases literally, by moving troops to occupy territory abandoned by the U.S.—meaning that any subsequent retaliation from Washington comes with an even greater risk than before, leading to further inaction. The effect, as in Syria, is to hand victory to Russia for as long as it can sustain the cost of Western sanctions or diplomatic isolation.

A similar story played out in Britain, where the full reaction to the Skripal assassination was slow-moving, taking months to play out. The cost imposed on Moscow—the loss of spies and networks around the world, as well as the damage to the Russian intelligence service’s reputation for efficiency and skill—was serious, but appears to have been absorbed. Moscow may have gone relatively quiet about Skripal (an October tweet by the Russian embassy in London linking to a Guardian story about Donald Trump expressing skepticism that Moscow was behind the poisoning is a rare recent intervention), but it has not changed its behavior.

And yet, the West has already been showing signs that it wants a thaw in relations. In August, the leaders of the world’s most powerful Western countries, the G7, met in Biarritz, France, where Trump suggested that Russia could be allowed back into the club. And he’s not alone in seeking to soften his country’s stance. The same month, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech saying that it was time for Europe to “pacify and clarify our relations with Russia,” arguing that pushing Moscow away would be a “profound” strategic error, and setting out opposition to any further economic sanctions on Russia. He has since repeated that message in an interview with The Economist and again last week in the run up to today’s NATO summit.

Those sanctions (which, along with Russia’s expulsion from the G8, were the result of the country’s annexation of Crimea) hit the Russian economy, but far from strangled it. In 2018, Russia’s GDP grew 2.3 percent. While growth is projected to slow in 2019 and 2020, Russia’s economy is nevertheless expected to continue to expand, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Since the October announcement, the U.K. has seen the Russian threat ease off, only for it to be replaced by other foreign-policy priorities: The future of the 2015 Iranian nuclear deal is uncertain and Tehran is testing the West’s collective patience; North Korea has resumed ballistic-missile tests; and months of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong have raised the specter of China taking more aggressive steps there.

But despite alleged British confidence—and clear Russian amateurism on occasion—it is clear that Moscow landed real blows in its 2018 communications battle with London. The U.K. was at times blindsided, fell into traps, made mistakes, and saw a worrying subsection of public opinion run toward conspiratorial skepticism. It is beyond doubt that Russia had some success muddying the waters of blame throughout the summer of 2018.

That may well have been enough for the GRU. With campaigning for the 2020 U.S. presidential election now well under way, the focus of Russian disinformation efforts might once again shift to the United States. Is it prepared for what is to come? What did Moscow learn from its six-month propaganda war with Britain?

“No matter what action you take against Russian intelligence services, they are going to put a massive amount of resources into a divergence campaign,” said Bill Evanina, the head of counterintelligence for the U.S. government. “Vladimir Putin's most amazing trait is his ability to deny that today is Thursday, and to convince people of that."

In Spiez, they know what that is like. “These people had us in the crosshairs,” Bucher told me. Who’s next?

Mike Giglio contributed reporting.

* First collage: Andrei Nekrassov, Getty, Max Ryazanov, Reuters, Shutterstock, Steve Taylor/SOPA Images, and Toby Melville.

* Second collage: Chris J Ratcliffe, EuropaNewswire/Gado, Getty, and Reuters

No comments:

Post a Comment