The hotel is a pleasant California bland—a yellowish four-story stucco number with a red roof and a fringe of palm trees. It’s about a half-hour drive from Napa Valley; it has four stars on Yelp even though one guest complained last year about bugs in his room. And for the past month, hundreds of Americans evacuated from cruise ships and Chinese cities have called it home.

For Yanjun Wei, the Westwind Inn on the 6,000-acre Travis Air Force Base looked like heaven last month after 30 hours in transit from Wuhan, China, the center of the coronavirus outbreak. She’d just been through hell trying to get back home to the United States. She had battled with the State Department for seats on an evacuation flight with her two toddlers. When her son, age 3, started “going crazy,” harassing his 1-year-old sister after the plane landed at Travis, she started crying and yelling at him; “I had a meltdown,” she told me. A friend sitting nearby came over to hold and soothe her from behind a face mask; another person in her row took charge of her daughter so she could deal with her son. Finally Wei’s family made the short trip from the tarmac to the hotel that would serve as their temporary home. For Wei, the worst was already over, even though she wouldn’t see her husband, Ken, who was waiting for her in San Diego, for the next two weeks.

[Read: What you need to know about the coronavirus]

Staff members and evacuees who spent time at Travis described a period of friendly confinement, with intervals of normalcy, extreme boredom, and surreal reminders of the invisible danger. What those conversations also revealed was a sense of solidarity and affection among people thrust into the same bizarre situation, who struck up friendships and found ways to help and entertain one another even under enforced social distancing. There are not many good news stories in the relentless coronavirus updates, but here is one: In circumstances of extreme stress and uncertainty, people forged lasting bonds and took care of one another.

“It was a great group of people. Both staff and evacuees,” said Frank Hannum, who spent two weeks in quarantine at Travis. His wife, Hope, who was also quarantined, put on ball gowns she’d brought with her to entertain the kids. Frank, an engineer, borrowed a laptop charger every morning from a stranger who left it outside his hotel-room door. They never met in person. “We were all kind of in the same situation, and we were just, you know, biding our time, making sure that we weren’t sick, our families weren’t sick, that we didn’t, of course, expose anybody else,” he said.

Base hotels such as Westwind are generally reserved for military members, veterans, civilian defense officials, and their guests, whether they’re moving among bases or on vacation, looking for a discount rate to see the sights. In many ways, the Westwind looks like any normal hotel, as you can see in videos from the Defense Department and evacuees—the rooms with their TVs and coffee makers and mini-fridges, the dim hallways with patterned carpet. It’s just that the guests are wearing masks or keeping six feet apart, fenced in on the grounds and guarded by U.S. marshals, and getting their temperature checked twice a day. The Java City café in the lobby is closed; the hotel staff are now Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Health and Human Services personnel. It’s much the same at the other three military hotels turned quarantine centers in Georgia, Texas, and elsewhere in California, which are taking in nearly 1,000 evacuees from a cruise ship this week.

Given the restrictions on social contact, forming a community required being inventive. Many of the evacuees used WeChat, the Chinese messaging app, to offer comfort, encouragement, and news to fellow guests they hadn’t even met, since many kept to their room for fear of infection. That’s also how Frank Hannum coordinated with his mystery laptop-charger benefactor. Some guests shared their notes from the daily CDC town hall to allow others to skip it, or alerted fellow evacuees when snack supplies were restored (since, as one of them told me, “those went by fast!”). Some staff members arranged a religious service by teleconference; participants, a CDC spokesman told me, could push pound-six to request a prayer.

For exhausted mothers like Wei, some of the kindness came in the form of child care. Several families with children wound up at Travis after evacuating from China. Wei and her kids, for instance, had been visiting relatives in Wuhan during the Chinese New Year when the government locked down the city and much of the surrounding province.

The staff organized outdoor activities for the children—catch and soccer games—in part to allow mothers a moment to take a nap or shower. “Think about it, the children are jet-lagged too,” Hannum said. “So for the first week, nobody’s getting any sleep.”

Both history and current events make it clear that fear of “the other” can permeate communities during an outbreak. As Jonathan Quick, a doctor and an adjunct professor at the Duke Global Health Institute, wrote recently in The Wall Street Journal, during the Spanish-flu outbreak of 1918, “Chileans blamed the poor, Senegalese blamed Brazilians, Brazilians blamed the Germans, Iranians blamed the British, and so on.” Racist incidents have been reported in Europe during the current pandemic; both the New Jersey governor’s office and the human-rights organization Amnesty International have recently felt compelled to remind people on Twitter not to be racist.

[Read: Trump’s European travel ban doesn’t make sense]

Despite the close relationship between disease and xenophobia, Quick told me that “the reflex to help one another is actually more common than one might expect.” In his article for the Journal, Quick cited the book Pale Rider, by Laura Spinney, which explains how the Spanish flu brought out good Samaritans: “In Alaska, 70-year-old Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy came out of retirement to fight the flu; in Tokyo, doctors went out at night to give free vaccinations to the poor; in Germany, the Catholic Church helped to train young women as nurses.” He told me that in his own medical work in crisis-hit areas, whether in Afghanistan or the Democratic Republic of the Congo, “I was always struck by these people who had been through awful things. When they had a chance … they really maintained a positive attitude and worked together, despite the tough times that they’ve had.”

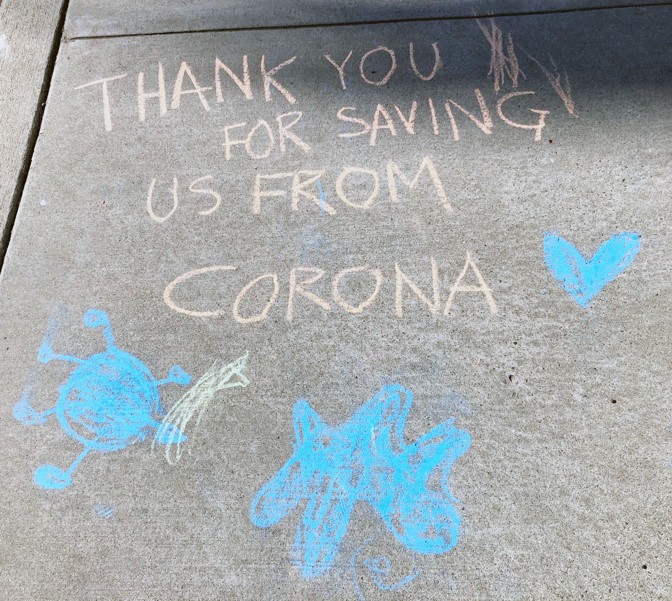

At Travis, this meant that Hope Hannum and another woman broke their boredom by drawing SpongeBob SquarePants and Pokémon characters on the walkways for the quarantined kids. Frank Hannum recalled one staffer who teared up after walking by a drawing of a virus with the caption “THANK YOU FOR SAVING US FROM CORONA.” Another evacuee, pining for red wine, got a gift from a staffer, according to a Wall Street Journal reporter who was herself quarantined at Travis: “four miniature bottles of vodka hidden in latex gloves.” Kristin Key, the comedian on the coronavirus-stricken Grand Princess cruise ship, who is currently in quarantine at Travis, told me that she heard there’s a ukulele circle, which she plans to join with her guitar.

At another quarantine site, Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, Matthew Price entered a haiku contest set up by the staff. His poem includes an affectionate nod to the staff’s personal protective equipment (PPE), which included masks, gloves, and medical gowns for when they got close to patients:

Please don’t spit on me

I’m wearing PPE

Love the CDC

This is not technically a haiku, and Price did not win the prize: Thai takeout, a respite from the monotony of the catered meals otherwise served three times a day. But the rules weren’t strict, and it was still a staff favorite.

The Hannums are now back in their small hometown outside Portland, Oregon, and oddly, Frank Hannum admits to feeling a touch of nostalgia for being in quarantine. Sure, it was boring, the food was so-so, and he and his wife were stuck together in close quarters for an average of 20 hours a day. But, he said, “we didn’t kill each other, which is great.” (He noted that they didn’t really have much choice but to work out whatever frictions arose over, say, clutter, because neither of them could actually go anywhere.) He hopes to put together a reunion for the evacuees, maybe a picnic next year. As he learned when he left quarantine, those people were special—not everyone is so welcoming during times of crisis. One night back in Oregon, when Hope Hannum was too tired to cook, the couple went out to a local Chinese restaurant. The proprietors knew where they’d come from. They asked the Hannums to leave.

No comments:

Post a Comment