The latest in the Ralph Northam scandal: A picture—of a man in a Ku Klux Klan outfit and another in blackface—from the Virginia governor’s medical-school yearbook page has thrown his tenure into tumult. Northam quickly apologized for the image, but claimed in a later press conference that he was neither of the people depicted. The revelation is a betrayal of the black voters who propelled Northam to office in 2017, under promises of ushering in a new era in Virginia’s history that would turn a page on its Confederate, white-supremacist roots, Vann R. Newkirk II writes. But more than Northam’s career is at stake: By remaining in office, argues Adam Serwer, he gives current—and future—public servants a way to squirm out of their own racist statements and actions.

Facebook turns 15 today. As the platform aged from scrappy dorm-room start-up to Silicon Valley behemoth, it’s transformed the social lives of millions, if not billions, of people. The platform has created a new category of relationships: the zombie friendship of Facebook friends who only vaguely keep in touch from afar through posts and updates on the site, extending a friendship far beyond its normal life span. Facebook’s meteoric rise has been predicated on a zealous belief in the power of “connection,” but that blinkered faith has led Facebook to undervalue how the site could be misused. (For more: Alexis Madrigal talks to people present for TheFacebook.com’s founding.)

Tell us: How old were you when you first joined Facebook, and do you remember why you joined? Has the way you use it changed over the years? What might cause you to leave the platform for good? Write to letters@theatlantic.com, and we may feature your response on our website and in future editions of The Atlantic daily.

Democrats are getting excited about a topic that makes many snooze: taxes. Representative Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Elizabeth Warren have both put out gargantuan plans to lessen income inequality by massively raising taxes on the über-rich: The former’s plan would hike marginal tax rates to nearly double what they are now, while the latter would target wealth such as property, assets, and even art. Both plans could be stymied by the same problem: an ineffectual IRS. For decades, the tax-collecting agency has been hamstrung by a lack of resources that the wealthy exploit to their benefit, leading to $18 billion in lost government revenue each year.

Evening Reads

(Jae C. Hong / AP)

When Chinese immigrants first moved to the United States, they forged their own ethnic enclaves to stave off discrimination. However, Chinatowns across urban America are now at risk of becoming historical remnants:

But now, as Baby Boomers and Millennials move back into center cities, Chinatowns are some cities’ hottest neighborhoods. Sale prices in Boston’s Chinatown were among the fastest-growing in the city in 2017, increasing by $285,000; one of New York City’s biggest condo projects is a $1.4 billion, 815-unit tower in Chinatown that features a 75-foot swimming pool, an “adult tree house,” and an outdoor tea pavilion. According to an analysis by the website Zumper, rents for a one bedroom in the “historic cultural” neighborhood of Los Angeles, which includes Chinatown, were $2,350 in June 2017—among the highest in Los Angeles, more than listings in popular neighborhoods such as West Hollywood and Silver Lake.

→ Read the rest.

(Mike Segar / Reuters)

Typically, the Super Bowl halftime show is an eye-popping sensory overload that complements the thrill of the game. But this year, Maroon 5’s underwhelming performance couldn’t enliven the most boring Super Bowl in recent memory:

To the extent that this halftime show will be remembered at all, it’ll be for outside factors: a boycott of the NFL triggered by Colin Kaepernick’s protests against racism; Atlanta’s queasy clearing of homeless camps in preparation for the Super Bowl; Tom Brady’s sixth ring; the trauma of seeing the Bud Knight’s skull crushed by a Game of Thrones brute. “Moves Like Jagger” is the sort of prescription-grade jingle meant to jam brain circuitry, but even it couldn’t, on Sunday night, whistle away the show’s dreary context.

→ Read the rest.

Have you tried your hand at our daily mini crossword (available on our website, here)? Monday is the perfect day to start—the puzzle gets bigger and more difficult throughout the week.

→ Challenge your friends, or try to beat your own solving time.

(Illustration: Araki Koman)

Dear Therapist

(Bianca Bagnarelli)

Every Monday, Lori Gottlieb answers questions from readers about their problems, big and small. This week, an anonymous reader writes:

“We recently moved to a new country and my daughter quickly made some friends who make me uncomfortable. Specifically, there is one boy who used spectacularly sexually explicit language with her in a text, which I find degrading and demeaning.

I found this out because after my daughter came home late from an outing with friends for her birthday, I used that as an excuse to go through her phone, as I’d suspected that there was something off about this boy. To complicate matters, he’s the son of a colleague.”

→ Read the rest, and Lori’s response. Have a question? Email Lori anytime at dear.therapist@theatlantic.com.

Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Email Shan Wang at swang@theatlantic.com

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.

It’s Monday, February 4.

President Donald Trump has nominated acting Interior Secretary David Bernhardt to lead the department. Bernhardt, an ex–oil lobbyist, will replace Ryan Zinke, who stepped down from the role in December following a year of scandals.

Speaking of Nominations: Trump told The Wall Street Journal over the weekend that he prefers to have acting Cabinet secretaries rather than permanent ones because “it gives me flexibility.” But no matter how much Trump likes flexibility, the Constitution doesn’t, argues David A. Graham.

Testing His Staying Power: Democrats are still urging Governor Ralph Northam to resign after a blog surfaced a photo of two people dressed in blackface and Ku Klux Klan robes in his medical-school yearbook. Northam, despite initially issuing an apology for the photo, now denies appearing in it but reportedly met with aides over the weekend to discuss the possibility of stepping down. If he does, Lieutenant Governor Justin Fairfax would take over for the rest of Northam’s term. Fairfax, though, is now facing some serious allegations of his own.

Trump’s Greatest Opponent: In the first month after recapturing the speaker’s gavel, Nancy Pelosi has emerged not only as the highest-ranking woman in the history of the republic, but also as the leader best able to frustrate and outfox Donald Trump, writes Todd S. Purdum. “Trump’s a silly man, and she knows it,” says one admirer. “He’s not going to be a problem for her.”

Done Biden His Time?: Former Vice President Joe Biden is leaning toward running for president, reports Edward-Isaac Dovere. But his deliberations now are focused on whether Democrats will support a centrist—especially one of his age. Another septuagenarian’s potential entrance into the 2020 presidential race might be the push Biden is waiting for.

Snapshot

Omar Castillo, an immigrant from Honduras who says that he is an actor, pretends to be President Trump as he sits with other migrants in the back of a platform truck during their journey toward the United States, in Matehuala, Mexico. (Alexandre Meneghini / Reuters)

Ideas From The AtlanticHow to Soak the Rich (Annie Lowrey)

“If the goal is to raise more money for redistributive policies and to ensure that millionaires pay their fair share, Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal isn’t particularly efficient. It might not even raise that much money, instead discouraging employers from paying workers more than $10 million or workers from trying to earn more than that threshold.” → Read on.

The NFL’s Truce With Trump Wasn’t Worth It (Jemele Hill)

“You might think the NFL’s strategic behind-the-scenes groveling and appeals to the president’s ego would have bought the league even more leeway with Trump, but on Sunday, Trump couldn’t resist throwing a jab at the league on its holy day.” → Read on.

Ralph Northam Should Go (Adam Serwer)

“If Northam remains governor, he gives license to any number of future scoundrels to remain in office despite engaging in bigotry against their constituents. There is more at risk here than Northam’s political career.” → Read on.

Democrats Overplay Their Hand on Abortion Rights (Alexandra DeSanctis)

“By defending more expansive abortion rights even in the face of these facts, Democrats are exposing an uncomfortable reality that they would rather not acknowledge: They embrace abortion as a woman’s right to end the life of her fetus at any stage—not the right to end her pregnancy.” → Read on.

◆Lobbyist at Trump Tower Meeting Received Half a Million Dollars in Suspicious Payments (BuzzFeed News)

◆Protesters Try to Storm Federal Jail in Brooklyn With Little Heat or Electricity (Annie Correal, Andy Newman, and Christina Goldbaum, The New York Times)

◆Insider Leaks Trump's "Executive Time"–Filled Private Schedules (Alexi McCammond and Jonathan Swan, Axios)

◆‘There Is Going to Be a War Within the Party. We Are Going to Lean Into It.’ (David Freedlander, Politico)

We’re always looking for ways to improve The Politics & Policy Daily, and will be testing some formats throughout the new year. Concerns, comments, questions, typos? Let us know anytime here.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for our daily politics email here.

There was a time when Facebook was small. After all, it only existed in one place on Earth: Harvard University, where Mark Zuckerberg was a sophomore. He lived in Kirkland House, a square of brick buildings arranged around a courtyard, one side hemmed in by JFK Street. For all the tendrils that Facebook now has snaked across the globe, it feels strange that one can pinpoint the moment it all began: 6 p.m. on February 4, 2004, as the temperature dipped below freezing on another day in Cambridge.

Within weeks, the social network would spread across the school; within months, the Ivy League. High schoolers arrived the next year, then college students across the globe, and finally anyone who wanted to in September 2006. Four years after it was founded, Facebook hit 100 million users. Four years after that, 1 billion. Now 2 billion people use Facebook every month. That’s 500 million more users than the total number of personal computers in use around the globe.

Sarah Goodin was there in Kirkland House too. She was a sophomore like Zuckerberg, and friends with Chris Hughes, another one of the site’s co-founders. So, shortly after it launched, Zuckerberg emailed her and asked her to try his new thing. As far as anyone can tell, she was the 15th total user. “Supposedly, I am the first woman on Facebook,” Goodin, now an exhibit developer and interactive designer at the California Academy of Sciences, told me.

She can’t quite remember her first impression of the site. “It was kind of a nonevent. He made this kind of stuff and we were buddies ... so, I thought, I’ll try it,” she said. “I don’t remember the time I first logged in being like, Oh, wow!”

But something did happen. She got a bunch of her friends to sign up. I don’t know for sure, but she was probably how I ended up on Facebook, because I, too, was in Kirkland House and was friends with Sarah Goodin.

There was no photo sharing, no News Feed, no apps, no games, no events. TheFacebook, in those first few months, was merely a database of profile pages of other people at Harvard. It combined the insularity and intimacy of an elite college with the user-generated network-effect frenzy of what was just beginning to be called Web 2.0. I’d been on the internet for more than 10 years at that point, and I’d never seen anything spread like that, not even Harvard’s anonymously run local file-sharing movie server, Llama, or its other, less couth file-sharing server, which distributed porn. TheFacebook conquered Harvard immediately and completely, and then it did precisely the same thing over and over again, whether it was with fishermen in Tamil Nadu or bus drivers in Ontario or high schoolers in Sarasota. Everything about Facebook has changed from then to now, except Mark Zuckerberg and the network’s ability to spread.

[Read: The education of Mark Zuckerberg]

Let’s stipulate that TheFacebook’s origins are contested by multiple people—famously, the Winklevosses, and less famously, Aaron Greenspan, another Harvard programmer. Local bulletin-board systems (BBSs) and early blogging approximated some of its pleasures. AOL Instant Messenger buddy lists and status updates made a kind of ambient social awareness de rigueur for young people in the late ’90s and early ’00s. Online communities—from The WELL to BlackPlanet to SixDegrees to Friendster to Myspace—predated Facebook by years. And competing systems existed at other universities, including Greenspan’s houseSYSTEM at Harvard and Columbia’s CUCommunity. To take a line from Mark Zuckerberg’s IM conversation with Greenspan discussing his dispute with the Winklevosses: “apparently the winklevoss twins are spreading that i took the idea for thefacebook from them,” he wrote, “as if there was an idea haha.”

And that’s actually right: The idea of the social network clearly was not important. Its features (profiles, statuses, a photo) were basically generic—implemented by scores of other companies—by the time the site was founded. What mattered about TheFacebook was how it worked, which is to say, how it made its users feel and behave.

Fifteen years later, Harvard students and faculty still remember those early months watching the new network generate a new kind of reality, one where your online activity became permanently entangled with your offline self, where a relationship wasn’t real unless it was posted to Facebook, where everyone was assumed to have an online presence.

This was the epicenter, even if we had no idea how big the quake would be.

The computer-science professor Harry Lewis was Harvard’s dean of students from 1995 until June 2003. He’d had Mark Zuckerberg in class, and had seen the young man’s attempts to build interesting things on the web. In late January 2004, a few days before Facebook was incorporated, he received an email from Zuckerberg. The subject line was “6 Degrees to Harry Lewis.”

Zuckerberg had scraped the Harvard Crimson archives and created a network map connecting people who’d been mentioned together in Crimson stories. As Lewis was the dean, he appeared in the paper more than anyone else. So, Zuckerberg wanted to know, would it be okay if he starred as the central node in this network, so anyone could see how they were connected to Lewis?

“I had a very interesting reaction,” Lewis told me recently. “I told him, ‘It’s all public information, but there is somehow a point at which aggregation of too much public information begins to feel like an invasion of privacy.’ So ‘invasion of privacy’ was actually in the very first email that I wrote to Mark Zuckerberg in 2004 in response to the first glimpse of the prototype.”

Lewis liked Zuckerberg. “I wrote back, ‘Sure, what the hell, seems harmless?’” he said. “And then I went on and nudged him, in true professorial style, about the inconsistencies and things that looked like bugs and [how] he hadn’t implemented each thing correctly.”

“Six Degrees to Harry Lewis” was a toy, but Zuckerberg was already looking at doing something real. What he decided to do was incredibly simple: make an online version of Harvard’s paper Facebooks, most famously the one handed to all incoming students, the Freshman Register, a book containing photos of one’s classmates along with their dorm residences—called “houses” at Harvard—and high schools. Other attempts had been made at creating an online version of it, one by Greenspan and others within individual houses.

Charlie Cheever was one of the first Harvard alumni to join TheFacebook, and eventually one of its key early employees. By 2004, he’d already graduated and gone to work at Amazon in Seattle. But he’d worked on the Crimson website while in school and still read the paper, which announced that the site had launched. Why was he reading the old school paper? “It’s hard to remember this, but there just wasn’t really a lot of stuff on the internet.”

But now there was TheFacebook. “You could edit your profile yourself, and the whole school was on it,” Cheever says. Instead of reading the pages of the paper, you could read the pages of your classmates. And that was what people did, clicking through profile after profile.

TheFacebook was a stunningly simple product. “It was really just a directory,” recalled Meagan Marks, another Harvard student who became an early Facebook employee in 2006. “Before [October 2005], you could only even have one picture.”

“There was the physical Facebook,” Goodin said. “This was an enhanced digital version of that. People understood the utility of a Facebook. That core functionality enabled it to spread, and the more that it spread, the more that it was capable of spreading.”

So what did people do now that they had the long-awaited online Facebook? Most of the people I talked with couldn’t really remember. “I don’t remember anything like ‘I’m going on Facebook to do this,’” Teddy Wright, another Kirkland resident, who is now a teaching associate at the University of Washington School of Social Work, told me.

“I remember staring at Facebook in my Harvard dorm room on my giant laptop (before wifi was widespread, back when you still had to be plugged into an Ethernet cable to get online) totally perplexed as to why this site was appealing,” Laura Weidman Powers wrote in an email to me.

Mostly, it seems, people went on Facebook to do nothing. But it was the best way of doing nothing.

They also poked people, which no one ever understood, even way back at the beginning. “My friends and I poked each other a few times to see what the appeal was, and I never got it,” said Weidman Powers, who went on to co-found Code 2040, a nonprofit dedicated to diversifying the technology industry. “However, I do have a friend who met his wife via Facebook poke, so go figure.”

By far the most cited common use was to check on someone’s relationship status, which now suddenly posed a new problem for couples. Defining or ending a relationship meant choosing a new answer in a dropdown; one of life’s enduring human messes now required an answer that a computer could understand.

But there were two features, long since disappeared or buried in obscurity, that were themselves useful, and that hinted at the power the data underlying the service could hold. The first was that you could see who else was in your classes. A new information layer now sat over the top of every class you were in. See someone interesting? Need help with homework? Now there was an entirely new route to reaching people you had class with. The second was that if you listed a band name—for example, Godspeed You! Black Emperor—as an interest in your profile, and then clicked on the link that generated, you would see everyone who had listed that as a favorite band. Any book or movie or artist suddenly had a visible network of people attached to it. “It struck me as a very efficient way to find communities of common interest around these pretty quickly, and this was a novel and very useful feature,” John Norvell, an anthropologist who was teaching at Harvard that year, wrote in an email.

And if you think about how Instagram hashtags work now, it’s not too far off from that very early vision. Courses showed the power that layering Facebook on top of existing real-life groups of people could have. And the other feature showed an enduring truth about social media: Liking certain cultural products and hobbies put you in a particular social grouping, according to the machine, if nothing else.

Norvell ended up thinking a lot about TheFacebook that year, as he’d just developed a new course called “Life Online,” which he taught for the first time the very semester TheFacebook launched. He lurked on the site and watched his students take to it.

“Facebook seemed to take over so fast,” Norvell said. “Expressions like ‘a relationship isn’t official until it’s Facebook official’ started to be heard right away.”

Heather Horn, now an editor at The New Republic, was an incoming freshman in the fall of 2004. Many of her classmates had signed up over the summer, so they never experienced a day on campus without Facebook. “Pretty continually through the next four years, I had people berate me that my three-year, rock-solid relationship wasn’t listed on Facebook,” Horn told me. “I remember my roommate’s boyfriend thought I must not be serious about my boyfriend, if he wasn’t listed on Facebook. I remember thinking that was just bananas.”

[Read: When you fall in love, this is what Facebook sees]

Of course, then as now, the romantic possibilities of TheFacebook were not limited to merely listing or checking a relationship status. Most people’s stories about the early service revolve around what Wright called “the flirtation machine.” People were thirsty, and here was the perfect blue oasis. “Facebook seemed like someone had taken the high-school game of deciphering people’s mental statuses and crush pursuits from AOL instant-messaging statuses and said, ‘How do we make this bigger and more all-encompassing?’” Horn said.

How exactly to approach someone on Facebook, though, was not entirely settled. Katie Zacarian was a senior who would go on to work at Facebook. She remembered a roommate calling her in to look at her computer screen. A fellow student had sent a message to her that said something like “Hey, you’re cute. Would you like to meet up?” But who was this guy? Nobody knew him. “We pored over his profile to [try] to figure out who he was and where she could have possibly collided with him on campus,” Zacarian, now an environmental-conservation technologist, said. “Being asked out by someone you’d never met nor ever seen in person was completely new to us ... In February 2004, it was hard for us to believe that a photo and a few things you wrote about yourself would prompt a guy to ask you out and, at first, seemed sort of weird.” (In the end, the roommate and messenger had a single, awkward date.)

Though cruising classmates was an embarrassingly common pursuit, TheFacebook wasn’t all dating. Norvell, one of the few faculty members with a profile in the early months, observed all kinds of interesting behavior from the students in and outside his classes.

“I remember that people took Facebook features like ‘liking’ and the various components of the profile back then to do creative and funny things with them, tons of inside jokes and multiple layers of irony,” Norvell recalled. “My own students wrote whole papers on what a ‘like’ could mean. I think all that took the Facebook developers by surprise, and they struggled to keep up with it. They expected much more literal uses.”

In other words, the culture of TheFacebook exploded in technicolor.

Thirteen days (13!) after launch, the future New Yorker editor Amelia Lester began a Crimson column about TheFacebook, joking, “For the uninitiated—all three of you ...” She then went on to detail a remarkably complete critique that could be applied to Instagram 2019 as well as TheFacebook 2004: “Just about every profile is a carefully constructed artifice, a kind of pixelated Platonic ideal of our messy, all-too organic real-life selves who don’t have perfect hair and don’t spend their weekends snuggling up with the latest Garcia Marquez.”

In a sense, everybody became Harry Lewis, the central node in the network. Facebook induced new behaviors along with the new pressures on the self. People became addicted, thirsted for the most friends possible, registered wry criticisms about the meaning of “friending,” and conscientiously objected to joining.

And if it’s hard to peg real three-dimensional people as one thing or another, TheFacebook not only made this possible, it practically required it. “Online social networks prove endlessly fascinating as long as I continue to subconsciously sort everyone I know into neat little categories,” Lester wrote.

But if the downsides of this new thing were obvious to the critical eye, what made people keep coming back and back and back? Lester had a theory there, too. “There are plenty of other primal instincts evident at work here: an element of wanting to belong, a dash of vanity and more than a little voyeurism probably go a long way in explaining most addictions (mine included),” she wrote. “But most of all it’s about performing—striking a pose, as Madonna might put it, and letting the world know why we’re important individuals. In short, it’s what Harvard students do best. And that’s why, wildly misleading photos aside, it would be difficult if not near-impossible to go cold turkey in the face of thefacebook.com.”

As Lester’s column implies, within weeks, Facebook’s first users had—like water rushing down a hill—come to occupy every position that it was possible to have on TheFacebook. So many of the behaviors that have come to dominate social media were visible right then, in miniature. Weeks in, Goodin noted, there were already “the ironic users,” who gave funny answers to the profile prompts and listed themselves as married to friends or roommates.

Almost everyone I talked with had a hard time remembering how the world was before this all happened. In particular, there is so much information about real people online now. Back then, information that linked a real physical person with their digital manifestations was sparse.

“That was really the first time that people ever made an account with their real name on it,” Cheever says. Before TheFacebook, “pretty much everything was like ‘Username: mds416.’ It was considered unsafe to use your real name. Cybervillains would come to your house and kidnap you.”

But TheFacebook borrowed some of the intimacy of the college environment to make this fairly radical step away from privacy feel safe. So people at Harvard, and then elsewhere, started giving more and more of themselves to the web.

[Read: Social apps are now a commodity]

“We were so open. For a while, anybody who ever went to Harvard could see whatever I posted,” said Natalie Bruss, a partner at the venture firm Fifth Wall, who was also in Zuckerberg’s class.

And so it went from school to school, establishing a new norm of how to be on the internet that was firmly enmeshed with how to be in college. An early marketing innovation, according to Marks, was that the company’s founders created demand at a school before launching there. “It meant people were dying to be on Facebook, so it launched with this high density, and that brought all this engagement early on,” she said.

A launch of TheFacebook created a frenzy. Who had time to think about the theoretical relationship between one’s online persona and the offline self? Later, there would be the real-names policy and Cambridge Analytica and the creeping understanding that we have all given the most sophisticated advertising mechanisms in the history of the world all the information they need to sell us things. Kids would get smart and switch back to usernames and private, ephemeral messaging platforms. A new, savvier generation is creating new norms. That’s good, but that’s not the same thing as returning to the world I took for granted until February of my senior year.

To watch these dynamics play out on ever-larger scales has been disorienting. The world should not be this perfectly fractal. And normally, it is too huge to comprehend: the millions of ways to live and talk and eat, the forgotten corners, deserts, farmers, bayou dwellers, towers in Singapore, welders in Accra, vaqueros, fly-fishing guides, hole-punch manufacturers, rare-earth-mineral-mining children, chocolatiers, shamans, and painters. But with Facebook, my dorm became coextensive with the world. This whole jumble of 2 billion people share something now, this thing called Facebook. There is almost nowhere on Earth that you can definitively say: There is no Facebook here and Facebook has changed nothing. Even the uncontacted indigenous people of the Amazon have gone viral.

I have wondered through the years whether another group of people could have accomplished this so quickly and so thoroughly. Was Mark Zuckerberg the only person who would have made this particular mark in the world?

And should I have seen it in him? When I was passing him on the way to a late-night bagel or some popcorn chicken, should he have glowed, predestined, charmed?

He really was just a guy. Cheever, a serious ultimate-Frisbee player, tells a funny story about Zuckerberg. He had met a great ultimate-Frisbee player, Mark Zuckerman, whom he wanted on the team, but at a tournament, Mark Zuckerberg signed up to play too. It was a windy day, and as Zuckerberg warmed up with a teammate, a gust of wind sent a Frisbee crashing into his nose. Bleeding, the poor freshman had to be driven to the hospital.

“So for two years of my life, anytime someone said ‘Mark Zuckerberg,’ I thought, Do you mean bizarro Mark Zuckerman? He was a joke character,” he said. “Then all of a sudden, here he is appearing in my Crimson newspaper.”

And that’s probably the best way to explain how watching Facebook take over the world feels to me. One minute, people are sending jokes about pokes and making detailed Friendster comparisons. The next, the thing has become central to all information flow and geopolitics.

“I often think about, you know, obviously Mark didn’t know it was gonna go this way. I still have his business card, from when his title was ‘I’m CEO, Bitch,’” said Goodin, the first woman on Facebook. “What’s weird is that it seemed like this kind of fun thing, and all of a sudden it’s a utility and it’s warped into something else that is not that great because of the way it has transformed social interaction.”

If it feels like a discontinuity, however, one thing has been constant from February 4, 2004, to today: Nothing in the world is better at getting people to put their selves on the internet. And there’s nothing more interesting than other people.

Was gym class a traumatizing part of school that still brings back shivers about that one particularly menacing bully? New research backs up what all too many of us already know: P.E. is kind of the worst.

Tell us: What was your childhood P.E. experience like?

Here’s how readers responded.

A handful of readers explained how gym class creates a culture where bullying thrives:

Twelve years old, entering high school, physically underdeveloped and socially challenged, I was a prime candidate for bullying. Our high school allowed upper-class students to choose where they spent their time during free periods. One of the options included the gym. There was a group of older students who spent their study time in the bleachers during my gym classes. To this day (I’m now 77), I remember their taunts and jeers as I participated in the exercises. They had a nickname for me, one I can’t say even after all these years, so real is the pain when I recall it, not because it was forbidden language, but because of the mocking way in which they used it.

A painful experience, yes, but suffering that was mitigated by my very wise eighth-grade teacher. He had taken me aside one day to tell me that my brain had developed faster than my body but in the long run that was an advantage, and that my body would catch up to my brain someday. That short piece of mentoring stayed with me through high school, enabling me to use my intelligence to attract friends and thwart enemies, succeeding where I could and minimizing those areas where success was beyond my reach.

Anne Hayes

Derby, Conn.

P.E. brings back memories of everything awkward about school and adolescence. Being picked almost last. Communal showering. Not being able to wear glasses because they might break, so therefore not being able to see, so therefore not being any good. As a girl in the ’70s, not learning how to play soccer, but having to memorize the size of the field; same for basketball and baseball. Don’t even get me started on dodgeball. The game where the kids who were already being picked on daily got battered, and it was sanctioned by the teachers.

The P.E. I was exposed to was not evil, just sad.

Marjorie Colletta

Alexandria, Va.

As an artistic, bookwormy type of kid, P.E. was my idea of a nightmare. Especially since at my school, the girls had to wear these hideous, shapeless, green polyester one-piece sacks that snapped on over each shoulder. The mean girls would chase after the nerdy girls (me) and yank at the snaps, making the top of the sack fall down while we were out on the field near where the boys were (in their non-sack-like T-shirts and shorts). And don’t get me started on how our gym teacher, whose whistle-adorned neck resembled that of a pit bull, used to look at me in utter derision when I klutzed my way through whatever activity we had that day. P.E. made me hate exercise even more than I did to begin with!

Pamela J. Kincheloe

Rochester, N.Y.

Girls’ P.E. in middle school was great. I learned to play volleyball. But I was the only Jewish player on the team and the Christian girls didn’t socialize with me. Sadly, they didn’t invite me to eat lunch with them. I’ve never forgotten that experience.

Donna Myrow

Palm Springs, Calif.

One reader recently rediscovered her P.E. report card:

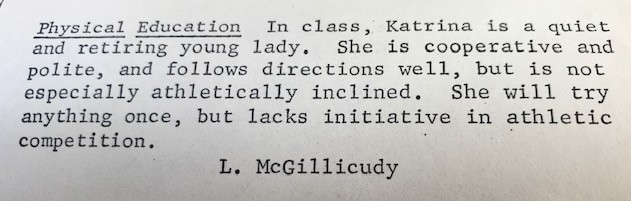

I recently came across my third-grade report card, from 1967. My P.E. teacher had commented that “Katrina ... is not especially athletically inclined. She will try anything once but lacks initiative in athletic competition.”

(Courtesy of Katrina Weinig)

(Courtesy of Katrina Weinig)Fortunately, I don’t think my parents ever showed me that report card so I never internalized its negative message! As it turned out, sports have been a major part of my life, on both the amateur and professional level. I’m turning 60 this year and, while I no longer compete, I still backpack, ski, scuba dive, cycle, swim, and ride horses, among other things. These sports have kept me healthy in mind and body, allowed me to share incredible experiences with family and friends, and brought me great joy.

Takeaway lesson for P.E. teachers: Encourage kids to find sports they can be passionate about. Competitive team sports aren’t for everyone, but with a little guidance and positive reinforcement, almost all people can find a sport they’ll enjoy and succeed at.

Katrina Weinig

Washington, D.C.

Forget gym class; for some readers, the locker room alone was anxiety-inducing:

I was in high school in Los Angeles in the 1960s, when gym class every day was mandatory and no one thought of questioning it. What was also mandatory was that everyone showers after gym class, and to ensure compliance, the gym teachers—all women—would stand at the entrance to the shower room checking off our names as we left. If they suspected that a girl had simply pretended to take a shower, they would pull her towel away to see if she had water drops on her naked body (many girls learned to splash a few drops on themselves so they could pass the test, as most of us preferred to shower at home). This felt not only tyrannical, but intrusive and embarrassing—and if you didn’t have enough showers on the teachers’ dreaded lists at the end of the semester, you got an “Unsatisfactory” in behavior on your report card.

Claudia Plimpton

Amherst, Mass.

In my seventh-grade gym class—in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1959—we girls had to line up each day in military fashion so the teacher could look down the collar of our droopy, one-piece gym suits to make sure we were wearing either a bra or an undershirt. If found wanting, we were called out, in all senses of the word.

Julia McGregor

Minneapolis, Minn.

I was in a public middle school (which was then called “junior high”) in the late 1960s in Louisville, Kentucky. We girls had to wear a horrible royal blue one-piece outfit with sort-of-bloomer legs and snaps up the front. I was small and thin and very physically inept. I shrank into the background as much as possible, but in team play that was impossible. The very, very worst memory, though, is that after class, we had to strip and take a big group shower. For girls going through puberty, it was the ultimate humiliation.

Caren Nichter

Martin, Tenn.

Other readers found ways to avoid participating altogether:

Being a music, drama, and English devotee, I found P.E. a horrible and jarring way to spend an academic period. It was the only subject I ever failed, due to my boyfriend’s trunk, which was my escape route to skip, skip, skip that harrowing high-school subject. Today I am a certified yoga teacher and yoga therapist and love to swim and hike, but would always choose to read a book before engaging in physical activity.

Susan Borofsky

Düsseldorf, Germany

I don’t blame it on the gym teachers or the classes. But I thought it was cool to always complain about my period. I took pride in doing as little as I could without getting in trouble.

Joan Chandler

Chicago, Ill.

What was gym class like to a nerdy, depressed adolescent? Torture. I loathed games, was an unpopular pick for teams, and dreaded gym class. Fortunately, Mrs. Pratt, our ancient gym teacher, had a policy of excusing girls with menstrual cramps from participation—with a “note” from a parent. I always had a “note.” I had cramps three days a week, every week, throughout junior high school.

Diana Dubrawsky

Silver Spring, Md.

In high school in Queens, New York, I menstruated with “horrible” cramps at least four times a month to avoid P.E. and the dreaded “gym suit.”

Yvette Sedlewicz

Garland, Texas

I hated it. Constant harassment. Team sports are evil. I finally stopped going. Got into trouble because of it. Did not care.

William Milne

Barrie, Ontario, Canada

Because it was 55 years ago, I have forgotten why we did this, but my best friend and I decided to protest P.E. We refused to put on P.E. uniforms one high-school semester. At the time, our school was giving number grades in every subject and the P.E. teacher gave us a 70—for merely sitting on the gym bleachers, I suppose. Those low grades in P.E. ruined our overall four-year grade averages. That protest cost us the valedictorian and salutatorian honors our senior year and it was a graduating class of 31 students. Since then, I think very carefully about what and how I protest.

Helen Albanese

Oakton, Va.

One reader found a way to customize P.E. to fit her needs:

Oh, how I hated P.E.! I hated my body, was terribly self-conscious in those awful gym shorts, and was terrified of being the weakest link in the team chain. Every week, weather allowing, my high-school P.E. class went for a 45-minute run through the woods around the school. My mother had recently been trying to get fit and was spending her mornings speed-walking through the neighborhood. I read an article in one of her fitness magazines about how a fast walking tempo was as good for you as going for a run. The next day I took the magazine to school, screwed up my courage, and confronted my gym teacher. He was a towering, gruff man and I was an overly sensitive, poetry-reading, theater-department geek. I stated my argument—“Scientific research shows that a brisk walk is as beneficial as a jog, therefore I plan to walk the jogging route at a fast pace instead of running.” I showed him the magazine article, said I had my mother’s blessing, and waited, shaking in fear, for the backlash. However, I was met with approval. My plan was allowed! I was the only one allowed to speed-walk, cementing my reputation as the weird one who did everything her own way. But the respect I had for my gym teacher grew and, I would like to think, his for me. I still grumbled while I fell behind in burpees, but I was pleased as punch speed-walking through the woods.

Amy McGriff

Delft, Netherlands

Many readers had positive experiences—one even discovered a lifelong love for distance running:

I enjoyed my childhood P.E. classes. They were a welcome break from the rest of the day and a fun way to release steam.

Mohammed Siddiqui

Doha, Qatar

I don’t remember much of what we did in gym class, but I do remember having lots of outdoor playtime regardless of the weather. If it rained, we still went out. If there was snow and cold, we bundled up. We played a lot of dodgeball and kickball and there were always jump ropes (double Dutch) going and we practiced shooting baskets from the basketball free-throw line. And here’s the best: We were taught dances of all sorts. I remember square dancing, but in particular I remember we learned the minuet. Of all things, the minuet? It was so not an East Chicago thing. Go figure.

Jan Clifford

South Pasadena, Calif.

I started kindergarten in 1974 in Northwest Florida, in the deepest of the Deep South. Two P.E. teachers team-taught in my elementary school, one male and one female, and I probably remember them better than most of my other teachers through all of K–12. They were very kind and made P.E. fun. They started a running program where we started out running a half mile each day and then built up to a mile. Some students chose to walk the distance, but I chose to run and discovered a lifelong love for distance running. I ran competitively in cross-country and track through junior high, high school, and college, which I attribute to my wonderful elementary-school P.E. teachers. I even got a small college scholarship after I was among the top-ranked Florida high-school women in the mile, two-mile, and 5K.

Yes, we played the much maligned game of dodgeball, but we also participated in a creative variety of games ranging from disco dancing to group activities with a silk parachute to my very favorite, field day with popcorn and snow cones afterward for 15 cents. Many of the activities were group-oriented rather than competitive, and they built community at the same time as they promoted physical activity. I also loved rainy-day P.E., with such classics as Heads Up, Seven Up, an indoor game played at tables which involved putting your head down, having one of the kids choose someone while everyone’s eyes were closed, and then trying to guess who was “it.”

I realize that not everyone has such idyllic memories of P.E. However, as someone who has struggled with depression as an adult, I think that P.E. and running together acted as a natural antidepressant that stabilized my mental health without my even realizing it. I probably would have had to start taking medication at a much younger age had it not been for developing a love for exercise early in life.

Karen Kruse Thomas

Baltimore, Md.

For me, P.E. was a godsend. I was a good student in school (straight A’s), and I owe it to some good teachers and to ... P.E.! We had class twice a day in grade school, plus during our long lunch breaks. All afternoon and morning, looked forward to getting out to play softball, football, dodgeball, rassle with the other guys, whatever. It enabled me to sit for the rest of the school day without too much agony.

Robert Sarracino

St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada

Finally, one reader had a recommendation for how to fix P.E.:

Students would be better off by starting each school day with 20 minutes of simple teacher-demonstrated calisthenics!

Michelle Miller

Toronto, Canada

“Ben Mezrich clearly aspires to be the Jackie Collins of Silicon Valley.”

It was the summer of 2009, and I had just published my book The Accidental Billionaires, about the founding of Facebook—which Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher would soon adapt into the Oscar-winning film The Social Network. I was on my book tour, bouncing from cable-news outlet to cable-news outlet, and at nearly every stop, Mark Zuckerberg’s refutation was waiting for me, passed along by his company’s spokesman, Elliot Schrage. I believed—and still believe—that what I had written was a fair and true telling of Facebook’s origins in a college dorm room, an almost Shakespearean drama involving socially awkward friends who had launched a revolution. Zuckerberg disagreed; at the time, his main concern seemed to be that I had implied that he’d founded Facebook to meet girls. A secondary concern seemed to be with the subtitle of my book—A Tale of Sex, Money, Genius, and Betrayal. When news of The Accidental Billionaires leaked onto the internet before publication, along with that subtitle, the word that seemed to rile up the biggest number of panicked missives from Facebook’s PR team was that kicker: Betrayal.

Who, the PR flacks kept asking, was betrayed?

A decade later, having watching Facebook grow into the multibillion-dollar, multibillion-user behemoth we know today, buffeted by scandals ranging from accusations of misuse of personal data to the Facebook platform being appropriated for election meddling, that question feels even more important. The answer gets right to the heart of what Facebook has become.

[Read: The thrilling Facebook creation myth]

Facebook’s origin story, as portrayed by my book and the movie, is well known. Late one night after a date gone bad, Zuckerberg made a website, FaceMash, which allowed his fellow Harvard students to compare female classmates based on photos he pulled from various dorm registries. When the prank site reached the attention of the Harvard administration, Zuckerberg was nearly kicked out of school for “breaching security, violating copyrights and violating individual privacy.” Though he managed to avoid any substantial punishment, he was written up in The Harvard Crimson, where he caught the attention of Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, the 6-foot-5-inch identical-twin Olympic rowers who couldn’t have been more perfect foils if they’d actually been invented whole-cloth out of Aaron Sorkin’s fevered imagination.

The twins were building their own social website, HarvardConnection, which later morphed into ConnectU, and were in the market for a coder. They reached out to Zuckerberg, who readily agreed to work for them. It was around that time that Zuckerberg went to his friend and classmate Eduardo Saverin and pitched him on an idea to create a new website, a place where people could connect, putting up their own profiles—a site that wouldn’t get him nearly kicked out of school. He asked Saverin to fund the endeavor; Saverin offered up $1,000, the most prescient investment in the history of the world, in exchange for the title of CFO and 30 percent of the company.

Weeks later, in February of 2004, after stalling Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss with a series of emails claiming he was too busy with classwork to finish their coding, Zuckerberg launched TheFacebook.com, which rapidly grew into a phenomenon. Zuckerberg ended up in California, where he met up with Sean Parker—and Eduardo Saverin, too, quickly found himself cut out of the story, his name erased from the Facebook masthead, his shares in the company diluted away.

[Read: Sean Parker’s lasting influence on Facebook explained]

The first few months of Facebook’s existence already offered plenty of candidates for the tail end of my subtitle. But the personal, dorm-room story was only one component of a much larger drama, still being played out on a global scale.

From the very beginning, Facebook wasn’t supposed to be just another social network—it was supposed to be a social revolution. Zuckerberg had never cared about making money with the site; in high school, he’d turned down a lucrative offer for software he’d developed, instead giving it away for free. As much as Saverin had pushed for Zuckerberg to figure out ways to monetize Facebook, Zuckerberg had never made that a priority. Instead, Facebook was supposed to be something “cool,” something that changed the world by changing how we interacted with one another. Facebook wasn’t some site you visited—it was a place where you lived. By sharing yourself among intersecting circles of friends, family, and colleagues, you became connected to an ever-growing village. The more you shared, the more connections could be made. Consequently, the less you protected your data, the better Facebook functioned, and the more powerful the revolution.

Yes, Zuckerberg created Facebook to help socially awkward kids like himself meet girls—but he was also intent on growing an online village designed to break down the barriers between people by changing our conceptions of privacy. Zuckerberg believed that the world was a better place the more we shared, whether we liked it or not. Although he’s seemed genuinely surprised at the privacy scandals that have hit Facebook over the years, nothing he’s done to break down our privacy walls has been unintentional. Privacy is antithetical to the engine that makes Facebook work. Privacy limits connection, whether it’s a connection with friends and family over a photo you put on your profile or a connection to a company trying to sell you something that you, according to your personal data, obviously want. This is the experience that Facebook was always meant to offer. The data you put on Facebook was never supposed to be private.

And this leads back to my subtitle, and to the concept of betrayal. From the very beginning, Zuckerberg has shown a pattern of deflecting and discarding things and people that don’t conform to his worldview or his ambition. In the same way that Zuckerberg discarded people like the Winklevoss twins and Eduardo Saverin in his quest to launch his revolution, he’s endeavored to shake off our fears about attacks on privacy and mishandled data. When we discover that our private information isn’t actually private, we feel betrayed.

And that’s why I believe I was right about Mark Zuckerberg—and why every one of us knows a little bit what it feels like to be a Winklevoss.

A man walks to an old farmhouse, his hands grazing stalks of grass, in a primal American image: something out of an Andrew Wyeth painting, or Days of Heaven. He’s greeted by his grandpa, whom he hasn’t seen in a long time. Inside the house sits a beautiful car. Is this real life? No, it is the hallucination of an office worker with a cashew blocking his airway. A colleague Heimlichs him back to reality, and he appears bummed to discover that he is not, in fact, dead.

This was Audi’s way of announcing that it would electrify its cars by 2025, part of a Super Bowl ad class that not-so-gently warned the viewer that consumer products would shape not only their life, but also their death. The commercial-break culture war of the past few years—brands image-washing themselves with gender-role reversals, multiculti montages, and Kendall Jenner wandering into a protest—seemed somewhat on pause, perhaps with the blowback to Gillette’s masculinity lecture too fresh. What instead emerged was a lurid, almost putrid sensibility, culminating in the eerie resurrection of Andy Warhol smearing ketchup on a soggy hamburger bun. Chunky milk, murderous nuts, flying reptiles barbecuing a barbecue: The end will be nasty, and it will not be in your control.

“IT’S WORSE THAN IT WAS YESTERDAY” read a fake newspaper headline in the home-security gizmo SimpliSafe’s Super Bowl spot, an explicit work of fearmongering that also featured an Amazon Echo–type device that malevolently spied on users. Amazon, meanwhile, advertised itself with an oddly chipper affirmation of the nightmares people have about its AI-adjacent products. The company infiltrated private spaces, as per Forest Whitaker’s Alexa-enabled toothbrush. It took command of a user’s credit card when Harrison Ford’s dog, wearing an Echo collar, stocked up on kibble. It hijacked civilization at a supervillain scale, with an Alexa-rigged space station taking down the country’s power grids. The point was that Amazon would never actually allow these things. But also, definitely, that it could.

The sense of mutating capitalism—of products gaining sentience then running amok with horrifying results—also defined one of Sunday’s more effective WTF moments. Bud Light has branded itself with a medieval shtick for years now, but on Sunday night a campy joust of beverage-affiliated warriors turned gruesome, with the reenactment of a Game of Thrones scene in which a hero had his eyes gouged out. Then a dragon swooped in and roasted Bud Light’s royal court, and the Thrones theme song started to play. Twist: This was an ad both for beer and for HBO’s biggest hit show. Another wall between discrete cultural-commercial kingdoms has fallen, and not even the stupidest mascots are safe from the ensuing chaos.

Bud Knight will be back, though, as no one—fictional or otherwise—dies in ad land. Hence Martin Luther King Jr. returned to the Super Bowl in arguably an even dicier context than the much-loathed Dodge spot from last year. The NFL has been buffeted by fans and celebs swearing it off in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick, who accused team owners of blacklisting him for his anti-racism protests. The league, on Sunday, tried to strike back with an ad-like montage of King’s words preceding the coin toss, which was overseen by King’s daughter Bernice King, U.S. Representative John Lewis, and former United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young.

“Humanity is turning the tide and our efforts must include bridge builders, strategic negotiators and ambassadors,” Bernice King tweeted on Sunday, an implicit response to critics on Kaepernick’s side. Social-justice leaders can and obviously do disagree tactically about when to build bridges and when to refuse to participate with alleged oppressors. But MLK’s words were being used, more than anything, for football’s own PR efforts against dissenters. They were, in effect, being weaponized against supporters of his own cause.

But the spookiest haunting, still, was by Andy Warhol’s ghost. The late artist’s spiel about the universality of Coca-Cola—“A Coke is a Coke, and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking”—provided the seed for a decidedly un-Warholian bit of doggerel used to hawk that drink. Warhol himself made an appearance, too, in a Burger King commercial that showed him sitting at a table and eating a Whopper on camera, at length. A pioneer of the postmodern blurring between art and ads, Warhol is an apt figure for such treatment, but also an ominous one. Count off another vertebrae engulfed by the snake eating its own tail.

The Warhol footage came from the Danish filmmaker Jørgen Leth’s 1982 documentary, 66 Scenes From America, and the original clip—of Warhol unwrapping the burger, eating it, sitting in uncomfortable silence, and then saying his name—made the kind of gnomic statement on consumerism that Warhol specialized in. Burger King rebroadcast it undoctored, save for, in both the 45-second TV spot and the nearly five-minute internet version, a flash of text: #EatLikeAndy. It also tried to mascot-ify him by handing out “mystery boxes” containing white-bob wigs before the game. Said the brand’s marketing materials: “You’ll know exactly what to do with everything that’s inside the box, and you’ll have your own 15 minutes of fame, or should we say, flame.”

The Warhol ad did make for one of the most arresting spots of the night, with silence and mystery cutting against the game’s loudness. And it’d certainly be hard to argue impropriety in a fast-food chain decontextualizing and commodifying a pop-art adman who famously admired Madison Avenue’s talents for … decontextualization and commodification. “Warhol’s great advance was collapsing any distinction between commercial and noncommercial modes of experience,” Stephen Metcalf wrote recently in The Atlantic, elsewhere citing his quote “Making money is art, and working is art, and good business is the best art.”

Even so, a line is being crossed. Warhol said that the ad-swaddled surfaces of modern life were canvases; now a corporation has taken not only his art but also his own likeness in the act of art making, and represented it as an ad. If he is the prime target for such treatment, there is no reason to think he’d be the only one. In an almost visceral way, the morbid mood of Sunday’s ads hinted at an expansion of Warhol’s 15-minutes-of-fame principle past the truism it’s already become. One day we will each leave this Earth, but our image no longer will. If gods or accomplishments or loved ones do not ensure immortality, at least the corporations might, as there’s no buyer that can’t also become a seller.

Michael Apa remembers the first time a patient told him she wanted her teeth fixed because she didn’t like the way they looked in selfies. It was 2015, and Apa’s patient was Huda Kattan, who had good reason to care about her smile: Kattan has leveraged her popular beauty blog and millions of Instagram followers to build a global cosmetics brand, Huda Beauty. In the process, her path to success has been dotted with thousands of close-up images and videos of her own face.

To perfect her teeth, Kattan opted for porcelain veneers, which have exploded in popularity in the past 10 years. Apa, an aesthetic dentist with a quarter-million Instagram followers of his own, documented her procedure on his YouTube channel. Although veneers have been used less glamorously for decades to help non-famous people with serious size or shape problems in some of their teeth, they can also be used to perfect someone’s already-nice smile beyond the capabilities of traditional orthodontia. Veneers start at about $1,000 a tooth, and for top-tier aesthetic dentists such as Apa, they can easily hit $3,000 to $4,000 apiece.

For years, using veneers to perfect already-good teeth was mostly confined to the professionally attractive and fabulously wealthy. They started to gain wide favor among traditional celebrities in the late 1990s and might have stayed confined to those rarefied circles were it not for Instagram. The platform’s cabal of mostly young, mostly female, mostly preternaturally attractive power users, often referred to as “influencers,” are under immense pressure to meet the same beauty standards as their traditionally famous—and often far wealthier—Hollywood counterparts. Now Apa hears the desire to look better in selfies all the time, from people with all kinds of jobs. “Every cosmetic procedure has just gone crazy in popularity since Instagram became a thing,” he says.

[Read: Who would spend $17 on toothpaste?]

These influencers have a different, more intimate relationship with their fans than the celebrities of the past, which has helped Instagram collapse any remaining gap between the things actors and models do to their bodies and what young consumers will aspire to (and spend money on) for their own bodies. As a result, influencers have begun to normalize a whole host of cosmetic enhancements, including veneers, for a generation of young consumers.

Dental veneers date back as far as 1928, when the pioneering aesthetic dentist Charles Pincus was asked by Hollywood studio execs to perfect the look of an actor’s teeth. That version of the procedure was temporary, and actors could pop off their perfect smiles at the end of the day. Now veneers are more permanent. Thin porcelain covers are glued to the fronts of teeth that have been sanded down to accommodate the addition, and they last at least 10 years on average. They’re in a tier of cosmetic procedures common among influencers, alongside things such as lip injections and Fraxel laser treatments: more invasive and longer-lasting than a good makeup application, but not as extreme or expensive as plastic surgery.

“[Influencers] have to perform traditional beauty,” says Brooke Erin Duffy, a communications professor at Cornell University. “If they don’t do enough and aren’t looking great, they’re going to get called out.” At the same time, there’s a risk of doing too much and looking too fake, which can turn fans against them, Duffy says. That puts Instagram stars in a bind that the veneers tier of procedure can ease: Audiences want to feel like they’re following someone authentic, but also someone who’s authentically prettier, richer, and happier than anyone they know in real life.

“Part of this is a push to stick with aesthetics that are safe and which do well, metrics-wise,” says Emily Hund, a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania who studies Instagram influencers. For many women whose accounts focus on fashion, beauty, or lifestyle, that includes adhering to basic norms of feminine grooming: flowing hair, even skin, a small waist, manicured nails, plump lips, and a straight, white smile. According to Hund, achieving those features drives positive engagement and helps accounts gain followers, which in turn better situates an influencer to make sponsorship deals and earn an income.

Often the easiest way for these influencers to generate money is to sell the tools of their own aesthetic achievement back to their followers, giving fans a way to replicate the look they admire. Kattan, for instance, started a beauty company that’s now worth a billion dollars by selling her own line of false eyelashes to her followers. But usually this strategy means partnering with a third party to endorse a product or service, which the influencer then receives for free, often in addition to payment for posts. That dynamic has helped a lot of influencers end up with a new set of pearly whites, free of charge.

“It’s almost hard to find an influencer without veneers now,” Apa says. When he expanded his New York City practice to include an office in Dubai in 2014, inviting the region’s Instagram stars in to get their teeth done was the primary way he built a new client base, he says: “It just completely changed the landscape of how I thought of attracting business and patients.” Apa notes that now up to 90 percent of his business in both offices comes from people who know about him from Instagram, and influencers and traditional celebrities alike seek him out. (The actress Chloë Sevigny and the reality-TV star Kyle Richards both recently appeared on his account.)

On Instagram, anything beloved by celebrities quickly finds a huge audience of normal users, hungry to experience the lifestyles of the rich and famous. “It’s mind-blowing how much influence social media has on people,” says Anabella Oquendo Parilli, a dentist and the director of New York University’s aesthetic-dentistry program for international students. While most people can afford a new lipstick or an occasional new pair of shoes, selling $10,000 worth of new teeth is something else. But social media is an environment where users expect to get a more intimate view of a person’s life, which sets the stage for influencers to recommend more than just clothing or makeup to their followers.

To meet that expectation, beauty and lifestyle influencers have created a class of Instagram-famous medical professionals such as the plastic surgeon Dr. Miami or the dermatologist Simon Ourian, who now have millions of followers in their own right. Being their patient has become a widely understood luxury good, like a designer handbag for your corporeal form, and it’s increasingly common to see cosmetic procedures advertised in the same ways as more traditional high-end status accessories on social media. A pair of Christian Louboutin shoes and a set of plumped-up lips cost about the same, and for a lot of young social-media users, they feel like similar consumer decisions.

Taking a medical procedure and recasting it as a marketable consumer good isn’t a simple process, but it’s one for which Instagram’s structure and culture work almost perfectly. It’s where you see what your friends had for brunch, one tap away from an internet celebrity showing off her new teeth. People’s ability to process those things separately just hasn’t caught up to the technology we now have at our disposal. “We use the framework we’d use for our friends and neighbors” when evaluating posts from influencers, says Duffy. “We have this expectation that social media gives us a glimpse into the ‘real’ person behind the scenes.”

[Read: When a sponsored Facebook post doesn’t pay off]

Social-media users now also live in an environment where they have far more opportunities to judge their own appearance than previous generations did. “You really get to see yourself age over however long you’ve had one of these phones,” says Apa. That creates pressure on regular users to perform to the same standards as the famous and wealthy. Those standards are aesthetic, but they’re also socioeconomic: It costs a lot of money to be that pretty. Instagram rewards people who perform beyond their economic lot in life, which spurs a whole host of purchases and can push people to less experienced, less expensive practitioners. Oquendo Parilli and Apa believe comparison photos on social media paint a vivid picture of what’s possible, but they warn that most depict work performed on someone who had good teeth to begin with. “A lot of people can take okay teeth and make them look white,” Apa says. “When there’s real complications, it becomes much more evolved and complicated, and requires much more experience.”

On the vast, unmediated plane of the internet, influencers do serve an important function that a lot of users find valuable. They’re a moderating force, filtering all the available products, services, and experiences that regular people don’t have the time to investigate fully. If you can find a couple of Instagram stars who share your personal style, they can help you redecorate your bedroom or pick a new winter coat.

But as consumers become more comfortable with Instagram as a place to shop, its ability to sell things spreads into more and more areas of life. The faux intimacy of influencer relationships and Instagram’s quick, seamless shopping infrastructure make the platform an effective advertising backdrop for all kinds of things, says Hund. “If you’re following an influencer and they tag their makeup artist or dermatologist, you can instantly click over to that person’s profile and maybe get an appointment,” she says. The combination of forces can be irresistible, even if you’re fully aware of how they all work. I may like my teeth just how they are, but I did look at them a little more closely in my bathroom mirror last night.

In December, Kate Julian asked why young people are having so little sex.

Julian devotes extensive space in her article to the ways in which [apps like Tinder] fail to bring people together, even for casual intimacy … But then she notes in a parenthetical that the impact has been very different in the gay and lesbian community. There, the apps have been much more successful, and active dating is much more common. “This disparity raises the possibility that the sex recession may be a mostly heterosexual phenomenon,” she says.

That’s a very important aside … It suggests … that men and women increasingly just do not know how to relate to each other in intimate situations. The feminists may well be right that it’s straight men who have more adapting to do, but if the evidence is to be believed both straight men and straight women are suffering from the situation they’re in and both have a powerful incentive to find a way out.

Noah Millman

Excerpt from a post on TheWeek.com

American women’s cultural and political power has grown exponentially over the last 30 years, and it’s likely that people are having less sex for the same reason they’re delaying marriage and children: It’s what women want …

I’m not sure that the current sexual “decline”—which is actually quite slight—is something to worry about. In fact, a lot of the concern seems to be part of a broader backlash against women’s rising autonomy.

Jessica Valenti

Excerpt from a post on Medium.com

Studies show young people are having less sex than previous generations. I knew I was ahead of my time.

— Conan O'Brien (@ConanOBrien)November 17, 2018

Julian is extending the economic sense of a recession, a period of temporary economic decline marked by a reduction in trade and industry … Let’s hope, then, we don’t see a Sex Depression.

John Kelly

Excerpt from a post on oxforddictionaries.com

Julian writes, “If people skip a crucial phase of development, one educator warned—a stage that includes not only flirting and kissing but dealing with heartbreak and disappointment—might they be unprepared for the challenges of adult life?” I read that and thought, Okay, so basically everyone’s a gay kid now. It used to be just the gay kids who made it to young adulthood without ever having dated or flirted or fucked or gotten broken up with. We watched our straight peers and siblings—with the encouragement of parents, educators, and the culture—date, go steady, hook up, lose their virginities … and learn to deal with heartbreak and disappointment. And for the most part, we gay kids didn’t get to do any of that. And still don’t, in places or in families where it’s not safe for young gay kids to be out. That’s why high-school-like drama tends to characterize the dating lives of a lot of young gays and lesbians. Because as young adults, we have to make all the same mistakes and learn all the same lessons that straight kids did back in high school and middle school.

Dan Savage

Transcript from Savage Lovecast

The bird-and-bee cover illustration for the December issue is charming, but I found it perplexing that the magazine chose to use a European robin (Erithacus rubecula) to represent the Platonic form of a bird rather than a North American species, considering the story that follows is primarily about U.S. trends. Why not the American robin (Turdus migratorius), a familiar bird whose understated beauty becomes apparent upon closer inspection? If you’re looking for a colorful, compact species like the European robin, why not the eastern bluebird (Sialia sialis), the state bird of Missouri and New York, or the American goldfinch (Spinus tristis), honored by Iowa, New Jersey, and Washington? The subtle orange splash found on the European robin’s breast has an approximate match in females of the Baltimore oriole (Icterus galbula), named after a city not far from The Atlantic’s headquarters.

Conor Gearin

Quincy, Mass.

Donald Trump likes to pit elite and non-elite white people against each other. In December, Joan C. Williams explored why white liberals play into his trap.

I appreciated this article, especially as I’ve learned that having conversations with working-class whites about economic issues often reveals that we share a lot of similar progressive views. But I’d also urge that this doesn’t need to be zero-sum. Concentrating on economic issues does not mean turning your back on issues of gender, race, environmentalism, etc. Economic inequality, gender imbalances, structural racism, and environmental devastation are not isolated issues—the same economic system that disenfranchises women and people of color is also pushing our planet to the brink of catastrophe. Democrats should be telling narratives about the interrelatedness of the issues that face our country and our world.

Andrew L. Guthrie

Portland, Ore.

I am a working-class black person and have always voted for Democratic candidates. However, I have come to conclusions similar to Joan C. Williams’s. The Democrats are far too invested in identity politics as a way to political victory and have abandoned millions of whites who supported them in the past.

Deonne Fulton Cooper

Kingstree, S.C.

Williams contends that “Democrats have banked a lot on the prospect that their voters’ anger can outmatch the anger of the voters who propelled Trump to office.” Implicitly, Williams seems to believe that the Democrats have focused their messaging entirely or primarily on anti-Trump and race-related ideas. This is quantifiably false. In the midterm elections, Democrats and outside Democratic groups spent more than half of all advertising dollars on health-care-related messages alone. Anti-Trump messaging was common, but messages rooted in economic populism dominated across all media markets. Williams specifically mentions “open borders” and taking the bait on immigration. But again, Democrats spent more advertising dollars on education, the budget, and taxes than on immigration. Clearly, Democrats do not “take the bait” on immigration to the degree that Williams thinks they do.

Davis Larkin

Chicago, Ill.

There is one very good reason Democrats cannot concentrate on the economy: Nothing can be done about the economy, so one might as well focus on other things.

Our free-market system, when left to itself, cannot help but produce tremendous economic inequality. Only government intervention can possibly correct this, and the American ethos of individualism anathematizes such regulation as “socialist.” Thus, so long as politicians are beholden to their corporate sponsors, they might continue making vague and vote-getting promises, but they will not do anything to improve the situation.

Besides, polls show that most voters are not particularly interested in the economy, but are more concerned (especially Trump voters) with threats to their status.

Stephen E. Silver

Santa Fe, N.M.

I’m a woman, 35, working-class, nonreligious, and I gladly voted for Obama in 2008. That was the last time I voted for a president, and my own lack of participation bothers me. But I don’t know what to do about it.

If I’d voted in 2016, it would have been for Trump, in large measure to vote against Hillary Clinton. And this article is dead-on accurate about everything I know to be true about the election and the frustration felt by middle America. For me, that frustration is mostly directed at my peers-of-a-different-class who arrogantly mock my very real questions, label me ignorant, and team up to hurl insults in my direction. I seem to trigger an angry response from these people, and I don’t understand why.

Here’s an example: An acquaintance posted a meme to Facebook a few days ago. It read, “While Trump had you focused on the migrant caravan, here’s what you missed at home,” then proceeded to list murders and almost-murders that had happened over a couple of weeks in America. I don’t understand how those things are related, or why anyone would be able to learn about one or the other but not both. I asked what the point of the meme was. Within minutes I was called a racist, idiotic Trump supporter—no joke. Four people belittled me, but zero gave an answer that wasn’t a rewording of the meme itself. Why is it easier to call me racist and dumb than it is to answer the question?

It’s therapeutic to see someone finally “getting it.”

Jodie L. Shokraifard

Greenville, Texas

For the third time in a century, Peter Beinart wrote in December, leftists are driving the Democratic Party’s agenda. Will they succeed in making America more equitable, or overplay their hand?

Peter Beinart’s article draws a parallel between today’s leftist energy and that of the progressive movements of the 1930s and ’60s. Beinart points out that the ambitious agendas of these movements were possible to achieve only with coordinated pressure applied by activists on the far left, including the occasional threat of disorder. He cautions that the newly energized left should be careful to convince the American people of its cause lest it face an electoral backlash like the ones faced by previous movements.

Perhaps caution is the wrong lesson to learn from history here. Many of the crowning achievements of the New Deal (such as Social Security) are still integral to society today. Similarly, the Voting Rights Act (albeit with some gutting by conservative Supreme Courts) and the Civil Rights Act endure. Even more recently, the Affordable Care Act has become part of the fabric of modern American society, and something that Republicans have had trouble finding the political will to dismantle (despite having controlled all three branches of government).

Truly useful progressive legislation can endure momentary electoral backlash by right-wing reactionaries; the newly energized left should focus on a new Voting Rights Act for the 21st century, radical reform of the criminal-justice system, federal jobs guarantees (or better yet, a universal basic income), and access to health care for all American citizens.

Ilya Nepomnyashchiy

Mountain View, Calif.

Employee emails contain valuable insights into company morale, Frank Partnoy wrote in September. Text analytics has other applications, too, he showed: According to recent research, a company’s stock price can decline significantly in the months after the company subtly changes descriptions of certain risks—which algorithms may spot more easily than people do.

I am compelled to respond to Frank Partnoy’s article, purportedly on the use of automated textual analysis to uncover corporate malfeasance. Mr. Partnoy cites only two examples: Enron and my company, NetApp. He concludes that a change to one risk factor in NetApp’s 2011 annual report subtly predicted deep trouble ahead: “Embedded in that small edit was an early warning. Six months after the 2011 report appeared, news broke that the Syrian government had purchased NetApp equipment through an Italian reseller and used that equipment to spy on its citizens.”

As our public filings show, we disclosed the Syria allegation explicitly and promptly, and we fully cooperated with the government. What’s more, the Department of Commerce determined that NetApp had not violated U.S. export laws, a fact that was not noted in the article.

The boring, but accurate, truth is that I made the risk-factor update shortly after I joined the company as general counsel in late 2010, to be explicit that our business model (like many IT-equipment providers) was largely channel-driven. When I made this small change, we were not aware of any Syria allegations, which first surfaced in November 2011, many months after the six-word edit on which your accusation of foul play is premised.

Matthew Fawcett

General Counsel, NetApp

Sunnyvale, Calif.

Frank Partnoy responds: