Jair Bolsonaro tomou posse nesta terça-feira amparado por um movimento que, apesar de recente no país, é constituído de elementos muito conhecidos de nossa história republicana. O bolsonarismo, o fenômeno que transformou um congressista radical do mais baixo clero em presidente, está assentado sobre três pilares: o autoritarismo militar positivista, o cristianismo conservador e o liberalismo autoritário.

O mais óbvio desses elementos é o autoritarismo militar positivista. Apesar de estar afastado do Exército há quase 30 anos, Bolsonaro ainda cultiva a imagem de soldado. É um patriota, um homem simples, incorruptível e disciplinado. Apartado da classe política tradicional e corrupta, ele é o único que pode resolver os problemas do país, reeditando o velho mito do Dom Sebastião de coturno.

Nossa república nasceu de um golpe militar contra a monarquia, liderado por republicanos civis (com predominância do Partido Republicano Paulista) e por militares entusiastas do positivismo. O próprio lema de nossa bandeira, em substituição ao brasão imperial, foi retirado das escrituras de Augusto Comte: “Ordem e Progresso”.

O historiador e filósofo uruguaio Arturo Ardao (1963) afirma que “no Brasil, o positivismo de Comte, como filosofia política, derivou-se da Sociedade Positivista do Rio, fundada em 1876 por Benjamin Constant”. Constant foi um dos mais importantes e influentes militares do Brasil daquele período. Ardao argumenta ainda que “apesar de ser Republicano”, Comte “era contrário ao liberalismo democrático”. Preferia o filósofo francês uma terceira via entre a aristocracia e a democracia, “baseada no que ele chamava de ‘ditadura republicana’”. Na visão positivista, para controlar e fazer avançar uma sociedade, é preciso um governo forte, apartado dos baixos interesses da política tradicional, capaz de modernizar a sociedade de cima para baixo.

Os governos de Deodoro (1889-1891) e Floriano Peixoto (1891-1894) encarnavam essa visão militar. Porém, os republicanos civis conseguiram tomar as rédeas do governo a partir de 1894, com Prudente de Morais.

Apesar do insucesso relativo no campo nacional, o positivismo sentou raízes profundas no Rio Grande do Sul, possivelmente por conta da histórica concentração de tropas naquela região de fronteiras secas do país. A constituição daquele estado, “escrita” por Júlio de Castilhos, refletia essa visão mais positivista da política. Borges de Medeiros, por exemplo, governou o estado quase que ininterruptamente entre 1898 e 1928. Um verdadeiro caudilho.

Talvez não seja por acaso que Vargas, Costa e Silva, Médici e Geisel – quatro de nossos seis ditadores desde 1930 – tenham nascido naquele estado.

A ideia positivista de “democratura” estava por detrás dos movimentos de 1930 e 1964. Ambos esses autoritarismos estavam baseados na ideia de um governo forte, centralizado e capaz de modernizar o Brasil de cima para baixo. A cereja do bolo era que eles se diziam representantes da luta contra a corrupção, o populismo e o comunismo.

O anticomunismo paranoico é outro pilar do bolsonarismo, manifestado em sua plenitude no “olavaodecarvalhismo”, já analisado por mim e outros autores no Intercept.

Aqueles que clamavam por “intervenção militar” durante os protestos contra Dilma. Esses que acreditam que só o Exército pode acabar com a baderna (política e social) e a roubalheira em nosso país são representantes tardios dessa tradição do século 19.

Teologia da danaçãoO segundo pilar do bolsonarismo é o cristianismo reacionário, fortemente influenciado pelo Velho Testamento. Quem já leu a Bíblia percebe que há uma grande descontinuidade entre os dois livros.

A mensagem do Cristo, presente no Novo Testamento, muito facilmente se presta a uma leitura “progressista”, como a da Teologia da Libertação.

Do Evangelho de São Lucas, há essa famosíssima passagem em que “uma pessoa importante perguntou a Jesus: ‘Bom Mestre, o que devo fazer para receber em herança a vida eterna?” Jesus lhe diz que é preciso obedecer aos mandamentos, mas complementa:

“Falta ainda uma coisa para você fazer: venda tudo o que você possui, distribua aos pobres e terá um tesouro no céu”.

Com a evidente tristeza no rosto do homem, Jesus completou:

“Como é difícil para os ricos entrar no Reino do Céu! De fato, é mais fácil um camelo entrar pelo buraco de uma agulha, do que um rico entrar no Reino de Deus”.

Em vez de “Deus é amor”, tem-se aí a teologia do “Deus é vingança”.Como compatibilizar essa mensagem clara e cristalina, com os pastores mi e bilionários que apoiaram entusiasticamente Bolsonaro? A mensagem fundamental de Jesus é de amor: “ame ao próximo como a ti mesmo”. Mas o que menos sai da boca desses fariseus é amor. Eles só vomitam ódio, rancor, desprezo, violência.

Jesus perdoou “certa mulher conhecida na cidade como pecadora”, Jesus impediu o apedrejamento da mulher adúltera, Jesus disse “não julguem, e vocês não serão julgados”, Jesus pregou que se deve sempre oferecer a outra face. Jesus disse “Eu não vim para chamar os justos, e sim os pecadores para o arrependimento”.

Na cruz, clímax da narrativa cristã, um bandido ao lado de Jesus lhe disse: “Jesus, lembra-te de mim, quando vieres em teu Reino”, ao que Jesus respondeu: “Eu lhe garanto: hoje mesmo você estará comigo no Paraíso”.

Como casar essa mensagem de amor, de empatia, de compreensão, de caridade, com a baba odiosa que escorre da boca desses pastores picaretas?

O fato é que eles esquecem Jesus e se apegam a passagens selecionadas e mais raivosas do Velho Testamento, em vez de “Deus é amor”, tem-se aí e teologia do “Deus é vingança”, que massacra os infiéis e salva apenas os escolhidos. Como no Livro de Samuel, em que Javé (um dos nomes de Deus) diz:

“Agora, vá, ataque, e condene ao extermínio tudo o que pertence a Amalec. Não tenha piedade: mate homens e mulheres, crianças e recém-nascidos, bois e ovelhas, camelos e jumentos”.

Eis o embasamento da Teologia da Danação.

A justificativa econômicaO terceiro pilar do bolsonarismo é o liberalismo de Chicago à moda chilena. Assim como o cristianismo – capaz de ser a base das atitudes de Madre Teresa, mas também do reverendo assassino Jim Jones –, a ideologia liberal pode ser usada para justificar objetivos diametralmente antagônicos.

De uma ideologia revolucionária, que defende o Estado Democrático de Direito e as liberdades econômicas (inclusive da circulação de capitais, mercadorias e trabalhadores), o liberalismo de raízes mais profundas no Brasil é aquele reacionário, que clama por um governo autoritário para ser posto em marcha. Chicago boys que mandavam “às favas quaisquer escrúpulos” – como disse Jarbas Passarinho durante uma reunião do AI-5 em 1968 –, felizes com a possibilidade de pegar um país autoritário e utilizá-lo como uma folha em branco, uma tábula rasa de seus projetos.

Chicago boys mandavam “às favas quaisquer escrúpulos”, felizes com a possibilidade de pegar um país autoritário e utilizá-lo como uma folha em branco.Como afirma o especialista em história moderna da América Latina Patricio Silva (1991), no caso do Chile, os “Chicago boys desempenharam um papel-chave na institucionalização da ditadura. Agindo como intelectuais orgânicos, eles elaboraram respostas sofisticadas para a latente contradição existente entre liberalismo e o autoritarismo político”. O discurso era que o país só havia vivido até então uma falsa democracia, na qual apenas grupos organizados tinham seus interesses atendidos, em detrimento da maioria da população.

“Eles enfatizavam a necessidade de um governo forte que fosse capaz de impor um sistema de regras gerais e imparciais sobre toda a sociedade, sem permitir a pressão de grupos de interesse”. Seria através desse grupo de abnegados que se conseguiria modernizar o país. Um grupo de interesse detestado por esses economistas são os sindicatos. Qualquer interferência legislativa ou de ordem sindical sobre os contratos de trabalho é vista como perniciosa. Não por acaso, a tal carteira de trabalho verde e amarela é uma das bandeiras do plano de governo de Bolsonaro.

No caso do Brasil, durante a ditadura, com o desmonte dos sindicatos e com a imposição de uma regra oficial que comprimiu o salário mínimo, o que houve desde o início foi uma forte tendência à concentração de renda, como demonstra Pedro de Souza (2016) em sua premiada e já clássica tese. Pedro é economista do Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas Aplicadas, o Ipea, e foi orientado no seu doutoramento em Sociologia na Universidade de Brasília por Marcelo Medeiros, que é o principal pesquisador sobre desigualdade de renda no Brasil.

Para esses liberais, porém, desigualdade não é problema. Eles acreditam que dando maior liberdade aos ricos, maior serão os benefícios sociais para todos no longo prazo. Ou, numa versão famosa no Brasil dos anos 1970, distribuir renda significa tirar recursos dos ricos, o que reduz o nível de investimentos e de crescimento econômico do país.

Em resumo, são esses os pilares filosóficos do bolsonarismo. Note-se que todos eles são defensores, apologistas ou plenamente compatíveis com o autoritarismo. Com o agravante de que talvez pela primeira vez em nossa história, um presidente assumirá o poder já contando com uma base assustadora de entusiastas fanáticos.

Quem chama político de “mito”, pode facilmente se confundir e acabar o chamando de “duce”.

The post As ideias do bolsonarismo já foram testadas e só trouxeram desigualdade ao Brasil appeared first on The Intercept.

The post Bolsonaro, Distopia com Bordão: é a Nova Era! appeared first on The Intercept.

Many of the world’s troubles are legacies of American intervention. In Iraq, there is the continuation of a war that began with the U.S. invasion in 2003. One of the casualties is an American citizen imprisoned in Iraq for more than a decade, a victim of torture, secret evidence, and witnesses who later recanted. Decades of U.S. meddling in Central America, and support for repressive dictatorships there, have undermined social fabrics; gangs are rampant, and if joining them is easy, getting out is not. In Yemen, where the Saudi-led war has been supported by the U.S. military, children are dying of starvation.

Photo: Nadia Bseiso

By Cathy Scott-Clark, Murtaza Hussain

Illustration: Clay Rodery

By Danielle Mackey

Photo: Samar Hazboun

By Alice Speri

Photo: David Guttenfelder/AP

By Maryam Saleh

Photo: AFP/Getty Images

By Sarah Aziza

Photo: Johan Ordonez/Getty Images

By Cora Currier, Danielle Mackey

Photo: Salvador Meléndez

By Danielle Mackey, Cora Currier

Photo: Alex Potter

By Alex Potter

Photo: Alex Potter

By Laura Kasinof

Photo: AFP/Getty Images

By Johnny Dwyer, Ryan Gallagher

Illustrations: Matt Rota

By Simona Foltyn

Photo: Jan Kuhlmann/AP

By Simona Foltyn

Photo: Mídia Ninja

By Glenn Greenwald

Photo: Fabio Teixeira/AP

By Glenn Greenwald

The post The Long Hand of U.S. Intervention: The Intercept’s 2018 World Coverage appeared first on The Intercept.

(Photo by David Goldman / AP)What We’re Following

(Photo by David Goldman / AP)What We’re Following10 new factors that will shape the Democratic primary (Edward-Isaac Dovere)

A pundit president, impeachment fever, grappling with the Obama legacy, and more. → Read on.

Elizabeth Warren doesn’t want to be Hillary 2.0 (Edward-Isaac Dovere)

“Operatives working for several other Democratic candidates about to make their own announcements have insisted she’s the Hillary Clinton of 2020—and not in a complimentary way. ” → Read on.

What was the Massachusetts senator trying to prove with her DNA test? (Sarah Zhang)

“So here we are: A national politician has taken a DNA test to prove her heritage. To which President Donald Trump, who has repeatedly mocked Warren as ‘Pocahontas,’ responded … ‘Who cares?’” → Read on.

Republicans used to force government closures in the name of fiscal restraint. Now? (Charlie J. Sykes)

“In the new Trumpian reality, the wall is worth it. Costly, crude, dumb, and obsolete, it is now central to the GOP agenda.” → Read on.

The year of the complicated suburb (Amanda Kolson Hurley)

“White-picket-fenced realm of white-bread people and cookie-cutter housing. That’s still the stereotype that persists in how many of us think about and portray these much-maligned spaces surrounding cities. But if there was once some truth to it, there certainly isn’t today.” → Read on.

Illustration by Paul Spella / The Atlantic

Illustration by Paul Spella / The AtlanticWhat does it mean to teach a person to surrender? (Matt Thompson)

“That word, miseducation, has been in the air … Every person has two choices for how to cope with any aspect of society that is uncomfortable: act to change it, or surrender. Miseducation is the art of teaching people to surrender.” → Read on.

Don’t go out tonight, on New Year’s Eve (Julie Beck)

“If you have ever turned on your television on New Year’s Eve and felt even a little bit jealous of the partyers gathered in Times Square to watch the ball drop, I want you to remember one thing: A lot of those people are wearing diapers.” → Read on.

2018: The year of the YIMBY (Kriston Capps)

“Not only did Minneapolis prove that a major American city could pass pro-housing zoning reforms beloved by Yes-In-My-Backyard types, it could pass them all at once, and without forcing the mayor to flee by cover of night.” → Read on.

A swimmer jumps into the Songhua River to mark the coming new year, in Harbin, China. See Alan Taylor’s full gallery of 2019 festivities, from the countries that have already crossed into 2019. (Photo by Tao Zhang / Getty)

A swimmer jumps into the Songhua River to mark the coming new year, in Harbin, China. See Alan Taylor’s full gallery of 2019 festivities, from the countries that have already crossed into 2019. (Photo by Tao Zhang / Getty)

This special edition of the Daily was compiled by Shan Wang. Concerns, comments, questions? Email swang@theatlantic.com

Were you forwarded this newsletter? Sign up for the daily email here.

Festive and colorful images from Australia, China, the United States, Spain, and many other countries around the world as people greet the new year with fireworks, polar-bear swims, traditional festivals, and solemn observations

A little over a year ago, Louis C.K. published a statement in The New York Times, after several women had come forward to confirm the rumors that had, for years, been swirling around him. “These stories are true,” he wrote, expressing regret for several instances of sexual misconduct and suggesting that the acts being made public would be a turning point for him. His confession concluded with contrition: “I have spent my long and lucky career talking and saying anything I want,” C.K. wrote. “I will now step back and take a long time to listen.”

The statement was, for all its labored hand-wringing—a literary critic might think of it as foreshadowing—not an apology. It was instead, like so much of C.K.’s comedy, notably self-centered. In its nods toward introspection, though, the statement was marginally better than the half-hearted defenses offered by many other men of #MeToo, and so it was accommodated, in many quarters, with relief and a great deal of patience: Maybe he could learn. Maybe he could do better. Maybe he could find a way to make amends to the women whose persons he had disrespected and whose careers he had compromised. C.K., with more TK: Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

But 2018 has been a year of hard truths, and here, just before the calendar turns its page to whatever fresh hell might lie in wait, is one more: C.K.’s promise to listen and learn, it seems, was itself a lie. On Sunday evening, instead, an audio recording of a recent appearance C.K. made, reportedly, at Governor’s comedy club on Long Island, New York, leaked on YouTube. The set suggests that while C.K. may have been up to a lot of activities over the past year, listening and learning have not been among them.

In the set—one of many unscheduled appearances he has made as part of a quiet comeback—C.K. makes jokes about the word retarded. (He bemoans being unable to use the word as an apparent compromise on his freedom of self-expression.) He mocks the activist students of Parkland, Florida, who have been trying to convert a personal tragedy into social good. (“You’re not interesting because you went to a high school where kids got shot. Why does that mean I have to listen to you? How does that make you interesting? You didn’t get shot, you pushed some fat kid in the way, and now I gotta listen to you talking?”) C.K. also mocks Asian men, and black men, and nonbinary people. (“‘You should address me as they/them, because I identify as gender neutral,’” C.K. says, dripping with sarcasm. “Oh, okay. Okay. You should address me as there, because I identify as a location. And the location is your mother’s cunt.”)

It’s the kind of comedy that is so lacking in depth or insight that it’s not worth examining, on its own, in any more detail. What’s notable, though, is the broader implication the new jokes represent for C.K.’s alleged efforts at redemption. Over the years, C.K.’s comedy evolved, as any comic’s will, but at their best and most well known, his jokes were about interrogating himself as a means of interrogating American culture. As C.K. shuffled uncomfortably on stages and sets, clad in rumpled T-shirts and slouchy dad jeans, he served as his own act’s useful idiot: C.K., author and character at once, played the privileged guy who—he’d be the first to admit it—didn’t fully deserve his privilege. It was classic observational humor, bending its lens to examine the warped terrain of C.K.’s own psyche, and while it was winking and postmodern and self-hating and self-elevating, it also contained an implied transaction: Hearing C.K.’s confession would offer, for his audience, its own kind of reconciliation. His performed selfishness could seem, in its twisted way, generous.

But while offense, in that sense, has always been an element of C.K.’s comedy—offense as a means of inflicting discomfort, and thus, the promise went, of illuminating awkward realities—offense, now, is all there is. The layer of alleged truth-telling is entirely missing from the new material. C.K.’s new set, according to its leaked version, doesn’t merely punch down; it stomps, pettily, to the bottom. None of it is smart or brave; it is simply cruel. And yet it tries to justify itself by suggesting that C.K. himself has been the recipient of cruelty. One of the key moments of the leaked set comes when someone, either by walking out or by shooting him a look, seems to question C.K. as he complains about being unable to use the word retarded. C.K. responds with a rant:

What’re you gonna take away my birthday? My life is over; I don’t give a shit. You can, you can be offended—it’s okay. You can get mad at me. Anyway.

It’s an old story: The guy who abused others, claiming his own victimhood. The man who has so much, still, complaining about what he has lost, with no seeming interest in or regard for the people he has hurt along the way. It’s not merely a violation of Poe’s law; it’s a much more basic affront. It suggests that empathy itself is a fair-weather attitude, fragile and tenuous and, in the end, inconvenient. Then: I will now step back and take a long time to listen. Now: You can get mad at me. Anyway.

It all makes for an especially petulant form of nihilism—and what’s especially tragic about the transformation is that it’s not at all isolated to Louis C.K. This period last year found many other people implicated in #MeToo expressing their regrets, seeming to take responsibility, and promising to do better. Harvey Weinstein said he would try to be better (“That is my commitment”). Kevin Spacey said he would be “examining my own behavior.” Charlie Rose said something similar. Mario Batali said. John Hockenberry said. Matt Lauer said.

A year later, however, the he saids that followed the she saids have been revealing themselves, again and again, to have been little more than empty performances. Charlie Rose and Matt Lauer and Mario Batali have been rumored to be staging comebacks. John Hockenberry wrote an essay in which he framed himself as a tragic hero, one deserving to play a key role in crafting a new cultural concept of romance. Kevin Spacey recently released a video in which, in character as Frank Underwood, he uttered the teasing line, “We’re not done, no matter what anyone says—and besides, I know what you want: You want me back.” Bill Shine, ousted from Fox News for his alleged efforts to cover up patterns of sexual abuse at the network, has been promoted to a job at the White House.

Earlier this month, another former Fox News executive, Ken LaCorte, announced that he would be establishing a new network. It will be helmed by Mike Oreskes, who was ousted from NPR last year after an investigation into repeated incidents of sexual harassment, and by John Moody, who left Fox in 2018 after writing a column that referred to the U.S. Olympic team as “darker, gayer, different.” As LaCorte put it to Politico, “I couldn’t have afforded either one of these guys had we not been in this crazy type of atmosphere … In a weird way, I’m actually a beneficiary of companies being hypersensitive.”

It’s all part of another old story: semi-apologies that, in time, nullify themselves. The status quo, reassembling to its familiar, fusty order. Louis C.K., who has been treating cruelty as a game since long before this year, seems to be hoping that he can benefit from “hypersensitivity” in a similarly warped way—and in his new brand of comedy are the contours of tragedy: lessons unlearned, abuses unaccounted for, the people who truly deserve their anger written, once again, out of the story. You could read C.K.’s evolution as a gradual loss of control, as a wayward id winning out over everything else. You could read it, as well, as something more strategic: a calculation that his core audience, now, is the red-pill crowd, with humor that is marketed accordingly. Either way, C.K. has reason to have confidence in his new brand of comedy: In person, his jokes about the inconveniences of empathy have been commonly met with laughter. And with enthusiastic applause.

An odd thing happened to the woman who came onto the scene as an anti-banking, anti-establishment, burn-down-the-castle revolutionary: Elizabeth Warren became the castle.

In the past few years, she raised millions of dollars to build a political machine. She began talking up policy issues beyond the bread-and-butter economic proposals she became famous for. She bolstered her foreign-policy credentials with trips abroad. She built up a large team of staffers who carefully engineered policy rollouts and email blasts. She became a front-runner in the 2020 presidential race.

But as she announces her exploratory committee—which is really announcing her presidential campaign—Warren wants to be the outsider again.

As always happens with front-runners, Warren has become a target. She’s considered less shiny than some of the newer firebrands, who have themselves become the anti-establishment. Operatives working for several other Democratic candidates about to make their own announcements have insisted she’s the Hillary Clinton of 2020—and not in a complimentary way. They describe her as overly cautious and cold, carefully curating her “authentic” moments and struggling to escape a relatively small issue—her claim of American Indian heritage—that’s threatened to overtake her entire candidacy. Her big speech just after Thanksgiving on “a foreign policy that works for all Americans” sounded a whole lot like Clinton’s focus-grouped emphasis on “everyday Americans,” several operatives argue. She even has Bernie Sanders threatening to run to her left.

Along the way, each spot of drama—from the heritage controversy to whom she might pick as her campaign manager—has been hungrily covered by the press.

No other candidate has experienced anything quite like this this cycle. Then again, no other candidate has built herself up into quite this kind of dreadnought.

On Monday, Warren tried to rewind history, reminding voters in a launch video of who she was before. With home movies and old news clips flashing on the screen, she talks about being the daughter of a janitor who became a university professor—and later, after the 2008 crash, a central figure in the national reckoning over the economic system.

“These aren’t cracks that families are falling into—these are traps. America’s middle class is under attack. How did we get here? Billionaires and big corporations decided they wanted more of the pie, and they enlisted politicians to cut them a fatter slice,” she says in the video, narrating from her kitchen.

[Read: Sanders and Warren are heading for a standoff]

At the core of the video seems to be a Clintonesque assessment of the 2020 campaign: This isn’t going to be pretty, this isn’t going to be poetic, but it’s too important to get caught up in all of that. Even her announcement’s timing of New Year’s Eve morning—to the bewilderment of the chattering class—had that feel: The whole announcement game is silly, so she might as well just get it out of the way now and move on to the real stuff.

“If we organize together, if we fight together, if we persist together, we can win—we can and we will,” she says toward the close of the video.

According to Warren associates who’ve spent the past year with her preparing for her bid, she sees the road ahead as a long, hard slog, where she puts together enough of a coalition between Clinton and Sanders voters to win. Will it be a movement like the ones that propelled Barack Obama and Donald Trump to the presidency, or like the one her primary run against Clinton might have been in 2016? No.

But, her advisers believe, she will win. That’s the thing about a dreadnought: It might not have as flashy a design, but it blows a lot of other ships out of the water.

“She knows that this is going to be a fight,” said a current Warren campaign adviser, who requested anonymity in order to discuss internal thinking. “She’s a fighter.”

Warren’s team doesn’t like the Clinton comparisons. They see any of that talk as reeking of sexism, people seeing one woman as the same as another woman because of their gender and aspirations. But so far, at least, the Clinton comparisons aren’t being made about any of the other women who have been just as obvious in recent months about their 2020 intentions.

Some Clinton-campaign veterans say they’re sympathetic to what Warren is going through, but their own trauma from two years ago makes them skeptical she’ll be able to get out of it. “I’ve just seen how hard it can be to escape the tailspin of negative stories,” one former Clinton confidant said recently.

The comparisons have turned other Clintonites into loud Warren defenders—witness, for example, the recent backlash at The New York Times on Twitter when it ran a story about Warren staffers’ alleged backbiting around her decision to take a DNA test to prove her American Indian heritage. As with the endless Clinton-email-server stories, they raged. They insisted that the Times was blindly taking down a strong woman over an issue that Republicans have tried to drum up.

Warren and her team have a response to anyone who tries to make her into Clinton: Martha Coakley.

Coakley, the former Massachusetts attorney general, lost what should have been an easy win—Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat in the 2010 special election—with a parade of gaffes. As a result, Scott Brown ascended to the Senate, ended the Democrats’ filibuster-proof majority, blew up hopes for Obamacare, and set the tone for the 2010 Republican wave.

[Read: 10 new factors that will shape the 2020 Democratic primary]

Two years later, when Warren launched her own campaign against Brown, all she got at first were stories about how she was the second coming of Coakley.

As in the launch video she released on Monday, she played up her Oklahoma roots and her economic-policy work—the likes of which made her a regular on The Daily Show and in appearances with Obama. In the end, the Coakley attack didn’t go on for long.

“What happened in Massachusetts is she had a chance to tell her story—her upbringing, what her background really is,” the Warren adviser said. “And on top of that, she was able to tell people about her fight.”

Now, with all the attention on her campaign and with trackers and reporters following her every move, Warren and her team think she can slowly, slowly do that again.

That word, miseducation, has been in the air. All year long, essayists, musicians, podcasters, and others have been revisiting Lauryn Hill’s masterpiece, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, on the occasion of its 20th anniversary. A sudden burst of cinema about conversion therapy began in early August with the premiere of Desiree Akhavan’s film, The Miseducation of Cameron Post. ProPublica published an interactive database in mid-October of racial disparities in U.S. schools, titling it “Miseducation.” It’s a strange word, with unusual resonances, so its sudden prevalence is striking. The culture is giving us a timely reminder that a school can be a curse.

Hunt for the origins of that enduring formulation, the miseducation of, and you will find your way eventually to an 85-year-old book, Carter G. Woodson’s opus, The Mis-Education of the Negro. You may already know it as a mainstay in some African American studies classes, thought of mostly as a dry paean to the importance of teaching black history. But dust off the book, and open it, and you’ll unearth something remarkable: a boldly argued, deeply perceptive autopsy of a pattern in human societies that very much persists.

Every person has two choices for how to cope with any aspect of society that is uncomfortable: act to change it, or surrender. Miseducation is the art of teaching people to surrender. To be miseducated, as Woodson had it, is not merely to be poorly educated, although that’s often a byproduct. Miseducation is a deeper evil, one that arises whenever an intrinsic trait, such as sexuality or ethnic heritage, is treated as a flaw to be overcome, rather than a gift to be developed. It is the process of teaching people to sand off pieces of themselves to fit into their society’s constraints, rather than teaching them how to shape that society for themselves.

The aftermath of that trauma, of being taught to diminish one’s own self-worth, to question one’s very right to take up space in the world, can engulf entire lives. Given the booster shot of a school or education system, it can swallow whole communities. This makes miseducation so enticing as a means of social control that it recurs again and again, in an endless variety of contexts.

Stories of miseducation echoed across 2018, in Lauryn Hill’s New Jersey studio, in Cameron Post’s fictional boarding school, in a scrap heap in rural Idaho, and beyond. Figuring out the common melody that courses through these disparate stories was what sent me back to Woodson’s book. What I found was not only a strikingly current set of lessons on how miseducation works, but a prescription for how to work against it.

There are few purer distillations of how miseducation works than conversion therapy. Alongside its sunny depictions of gay and lesbian comings-of-age, 2018 featured two feature films depicting the practice: Boy Erased and The Miseducation of Cameron Post. The latter film takes place in the ’90s in a Christian boarding school called God’s Promise, which is dedicated to ridding adolescents of their same-sex attractions. But the movie hints that the process it describes isn’t limited to making students detest their sexuality alone. It has in mind a much larger history of miseducation in America—a savaging of cultures and identities that began before the nation’s founding, and continues today.

The students at God’s Promise are instructed to fill out their “icebergs,” a drawing on which they write out the hidden traumas or inner deficiencies presumed to lie beneath the surface of their same-sex attractions. The camera lingers for a moment on each student’s iceberg, as the movie’s eponymous protagonist, Cameron Post (played by Chloë Grace Moretz), tries to figure out what she should write on her own. One of the icebergs belongs to Adam Red Eagle (Forrest Goodluck), whose long black hair suggests his ethnic heritage as one of the Yanktonai people. “Yanktonai beliefs conflict with the Bible,” says Adam’s iceberg, listing the supposed roots of his sexual desires. The school’s stentorian headmaster, Lydia, yanks Adam’s hair into a rubber band early in the film, accusing him of another trait written on his iceberg: “hiding from God.” Late in the film (mild spoiler here), we see her shaving the flowing locks off his head, a development the movie sits with for just a moment before moving on.

But the shearing of Adam’s hair has quite a lot to do with miseducation. When those who were here before the Mayflower had been brutally decimated by the consequences of its arrival, Congress authorized the creation of boarding schools intended to strip Native American youth of any such traces of their heritage. These schools also engaged in conversion therapy, repressing not the students’ sexuality, but their culture. NPR’s Charla Bear reported on the schools in 2008, long after many of them were closed. She spoke to Bill Wright, a Pattwin Indian who was sent to Nevada’s Stewart Indian School in 1945, when he was 6 years old, and recalled instructors at the school “bathing him in kerosene and shaving his head.”

“Students at federal boarding schools were forbidden to express their culture—everything from wearing long hair to speaking even a single Indian word,” reported Bear. “Wright said he lost not only his language, but also his American Indian name.”

“I remember coming home and my grandma asked me to talk Indian to her and I said, ‘Grandma, I don’t understand you,’” Wright told Bear. “She said, ‘Then who are you?’”

These schools were championed by a man named Richard Henry Pratt, who would have been thought of by his counterparts as progressive by the standards of his day, the very picture of a well-meaning white liberal. The earliest reference to the word racism in the Oxford English Dictionary comes from a 1902 discussion with Pratt in which he inveighs against racial segregation. “Association of races and classes is necessary to destroy racism and classism,” Pratt said.

Pratt’s prescription for the ills of segregation was not cultural mixing. He had no interest in “Indians” commingling with whites. What he had in mind instead was cultural genocide. “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres,” he said. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

To Pratt, this was the only logical, even noble, conclusion. Only the culture of the whites was to be permitted to exist; all else was savagery. The silver lining he saw in the great evil of slavery, he said by way of example, was “the greatest blessing that ever came to the Negro race—seven millions of blacks from cannibalism in darkest Africa to citizenship in free and enlightened America.”

So every trace of the indigenous culture was to be destroyed, by force if necessary, but by miseducation if possible. A government report from decades later, combing through the grim wreckage of Pratt’s campaign, marveled at the teachers’ dedication to that task above all: “When asked to name the most important things the schools should do for the students, only about one-tenth of the teachers mentioned academic achievement as an important goal,” the report said. “Apparently, many of the teachers still see their role as that of ‘civilizing the native.’”

“When you control a man’s thinking,” Carter G. Woodson wrote in 1933, “you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his ‘proper place’ and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.”

The children’s native tongues were clipped from them, their hair was ripped from them, their clothes were stripped from them, and they were sent to live in the white culture, in hopes that they would find white tongues and hair and clothes. In many cases, they did not. “As a result,” the report found, “many return to the reservations disillusioned,” bereft of the great asset of their cultures.

Grandma, I don’t understand you, they would say. And their grandmothers would respond, Then who are you?

Never forget that a school can be a curse.

The nature of miseducation is viral; once infected, you run the risk of passing on your own miseducation to another. This means that all miseducation stories, Woodson’s included, are saddled with an unreliable narrator from the beginning. And few narrators are more compelling and challenging than Lauryn Hill.

In The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, the artist expounds gorgeously on the hard-won knowledge she earned on her ascent to the height of the music industry and into motherhood—lessons on love and money, fame and family, power and principles. Twenty years later, as Hill toured with these songs in 2018, the album still felt like a message out of time, as resonant as it ever was, despite the fact that Hill was just beginning her 20s when she made it. In the confidence of her flow, the lavish rasp of her alto, the iconic, unmistakable production choices, she sounds impossibly wise, wiser than most grown-ups could ever hope to be.

In the spring of 2018, Cardi B and Drake each released hit singles sampling “Ex Factor,” one of the album’s most splendidly crafted jewels. When Cardi performed her single, “Be Careful,” on Saturday Night Live in April, a zooming-out of the camera mid-song revealed to the audience watching at home that the singer was pregnant, to cheers from the studio audience. Cardi is just a few years older than Lauryn Hill was at the time of Miseducation’s release, when she too decided to become a mother. And like Hill, writes Joan Morgan in her book She Begat This: 20 Years of the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, Cardi was also facing “criticism from women who questioned the wisdom of having a child at a high point in her early career.” Such criticism had helped to fuel one of Hill’s most potent songs, “To Zion.”

The power of Hill’s love letter to the blessed son the world had told her not to have is palpable. But as Morgan notes, the song also had a striking political subtext. “In the ’90s black women were squeezed between competing narratives,” Morgan writes. “Mainstream feminism still championed the idea that women should be able to have it all. ‘It’ being career, marriage, great sex, kids, etc … The ’90s was the era of Waiting to Exhale. There was so much pressure for black women. The pressure to get chosen. The pressure not to be a statistic. The pressure to do it the ‘right’ way, all while well-publicized stats on drastic declines in marriage for black women constantly reminded us that having the option was increasingly a statistical improbability.”

Hill’s talent was unquestioned, and she was making some of the biggest-selling music in the country, yet she was told that having a child would derail her career. Against that backdrop, Morgan writes, “To Zion” was a powerfully subversive affirmation of a woman’s right to choose. “There are so many ways it could have gone left,” she writes. “Strongly evangelistic with distinctly gospel overtones, it could have been the perfect pro-life track and yet Hill beautifully and vulnerably created a vehicle that tenderly supports choice.”

But there were some choices Hill didn’t support. The irresistible catchiness of “Doo Wop (That Thing),” the most straightforwardly didactic song on the album, takes some of the edge off Hill’s moralizing. Yet that song, more than any other on the album, teases Miseducation’s central puzzle: How can we be sure the album itself is not a miseducation? “Look at where you be in,” she chides, “hair weaves like Europeans, fake nails done by Koreans.” Hill acknowledges in the song that she is not perfect—“Lauryn is only human”—but many have stepped in to ask the question implicit in her lyrics: What life lessons should we be taking from a song that’s gonna begrudge a girl a weave?

In light of the events in Hill’s life and career right after Miseducation, the question only grew stronger. The acclaim that surrounded the album gave way to years of litigation over compensation and credit. According to Touré’s 2003 Rolling Stone story about Hill, she grew increasingly alienated from many in her social circle in those years, seemingly in thrall to a spiritual adviser called Brother Anthony. In 2013, under apparent legal and financial duress, Hill dropped a surprise track—“Neurotic Society (Compulsory Mix)”—that touched off a controversy about gender expression and sexuality. The song was harder-edged and more staccato than anything else in her catalog, its lyrics a stream-of-consciousness assault on the fallen state of human affairs. Her queer fans struggled to know what to make of her references to “girl men,” “drag queens,” and “social transvestism.” Hill made clear that she wasn’t trying to be a public role model. “If I make music now, it will be to provide information to my own children,” she told Trace Magazine’s Claude Grunitzky in 2005. “If other people benefit from it, then so be it.”

Miseducation requires no lack of empathy or compassion. A genuine conviction about a person’s best interest offers no protection against leading that person astray. In his book, Woodson directed his most scathing criticisms at “highly educated Negroes,” victims of a system that made them contort themselves for its benefit, who’ve gone on to become the defenders and perpetrators of that same system.

“It may be of no importance to the race to boast today of many times as many ‘educated’ members as it had in 1865,” Woodson wrote. “If they are of the wrong kind the increase in numbers will be a disadvantage rather than an advantage. The only question which concerns us here is whether these ‘educated’ persons are actually equipped to face the ordeal before them or unconsciously contribute to their own undoing by perpetuating the regime of the oppressor.”

Between the songs on Hill’s Miseducation are interludes, recorded in Hill’s living room, in which the activist and educator Ras Baraka has a conversation with a group of kids about how they are learning to perceive the world. After “Lost Ones”—the album’s lyrical, danceable bullet to the heart of Hill’s former lover and collaborator, Wyclef Jean—Baraka is heard asking the kids to name a song about love.

“Love!” replies one of the boys in the room.

“There’s no song called ‘Love,’” Baraka responds.

“Yeah!” the boy exclaims. “It’s by Kirk Franklin!”

The song, Franklin’s gospel ode to 1 Corinthians 13, probably just hadn’t reached Baraka’s ears yet; it was from God’s Property, the hit album that was probably fresh on the charts when the classroom discussion was being taped. “The nights that I cry you love me,” Franklin’s choir sings. “When I should have died you love me / I'll never know why you love me.”

One of the girls in the class soon names “I Will Always Love You,” and the chat moves on. But I’ve always been struck by that young man, asked to name a love song, choosing one that rests on the mystery of God’s enduring love.

In the late ’90s, when Miseducation was recorded, Ras Baraka was an activist and educator in an occupied school district. The state of New Jersey had recently taken over control of Newark public schools. That was still the case in 2010, when Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg gave Newark $100 million to transform its education system. The gift, as Dale Russakoff recounts in her definitive book, The Prize, reflected a grand bargain between Zuckerberg and Chan, Newark’s then-mayor Cory Booker, and New Jersey’s then-governor Chris Christie. The three parties sought to demonstrate that with the right leadership, empowered by the state to put in place new, proven approaches to education, Newark’s schools could become a model for cities around the country in only five years. That aim, Russakoff argued, helped to doom the popularity of the group’s reforms among residents. “The language of national models,” she wrote, “left little room for attention to the unique problems of Newark, its schools, or its children.”

Baraka, raised in Newark by the city’s renowned black radical poet Amiri Baraka, knew well the power of a school to shape a society. And he was deeply attuned to the dangers of miseducation. A scene in the documentary series Brick City shows him addressing an auditorium of students after one of their classmates was shot. He beseeches them not to surrender to the climate of violence and poverty that surrounds them. “This is not normal,” he rages. “I want you to know it’s not normal. You live in this life like it’s normal. It is abnormal—to go to school, to talk about your friends dying, to not be able to walk home safely from school, to be jumped every other day, to fail everything, to live in squalor, to have people’s parents coming outside fighting with them in the middle of the street … And don’t take it like because it’s happening, that mean you tough. It only mean that you oppressed. And our job, override oppression?” He chuckles, darkly.

Baraka’s prominence and success as an educator helped catapult him onto the Newark city council, where he became the face of the opposition to Cory Booker’s education-reform agenda. The two men—Baraka a child of Newark, Booker a product of its suburb, Harrington Park—offered dueling diagnoses of the ills plaguing Newark’s students. To Booker, miseducation would mean living with public schools that had demonstrated little capacity to educate their children. To Baraka, it would mean fixating on public schools as the primary agents of that failure, rather than addressing the bog of poverty many of those students were mired in. They were both black men, abundantly gifted with the ebullience, intelligence, and passion that mark great politicians. Yet each presented a different vision of what it would mean to teach the city’s students to surrender. Again, the question presses: If miseducation is viral, who is there to trust?

In the title track of Miseducation, Lauryn provides her answer: Turn inward. On an album punctuated with irresistible beats, it would be easy for “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill,” a pure organ-and-strings gospel ballad, to feel like bland self-affirmation, an up-and-comer’s update on “The Greatest Love of All.” But because Hill invests the song with her richest and most expressive vocal runs, the lesson wields power. “Deep in my heart, the answer it was in me,” Hill sings, “And I made up my mind / to define my own destiny.” When miseducators abound, it stands to reason, one can only trust oneself.

The aftermath of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, the years of alienation and financial and legal struggle, demonstrated some of the risks of following only an inner compass. Navigating the folkways of human society requires something more: an education.

Carter G. Woodson had been an educator for more than three decades by the time he published The Mis-Education of the Negro. During his remarkable career as both a scholar and an educator, he accrued an extraordinarily varied catalog of the ways that education works, or doesn’t, across a vast range of cultural contexts.

Woodson was born to parents who had been enslaved. He grew up with little formal schooling, mining coal in his formative years in West Virginia. He entered high school at the age of 20, and sped through school to acquire his diploma. Just before Kentucky banned integrated schooling, Woodson studied at Berea College alongside white classmates from Appalachia. Next was the University of Chicago, then several years of teaching in the Philippines, then a six-month tour of the world’s education systems, from Malaysia to India to Egypt, Palestine, Greece, Italy, and France. He taught in D.C. public schools, sat on the faculty of Howard University, and along the way, earned a hard-won doctorate from Harvard.

What Woodson discovered in his career-long survey of the world’s school systems was that the education of African Americans was being conducted under the same blinkered premises that had governed Pratt’s boarding schools for Natives. They were being trained to fit into a white society, judged according to white parameters, and taught a white revision of their history. Their needs, environments, and experiences were systematically devalued, and when the knowledge they were fed proved un-useful to them, that failure was held up as a marker of their inherent deficiencies. It was conversion therapy in a different guise, its evils amplified by segregation.

Alongside this process of miseducation, however, Woodson saw other, more effective approaches. During his years in the Philippines, for example, he observed the failure of well-credentialed American educators—“men trained at institutions like Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Chicago”—to successfully teach Filipino students. But he marveled at the success of an unnamed “insurance man,” unstudied in the craft of teaching, who nonetheless “understood people.” At first, Woodson wrote, the man eschewed textbooks, “because those supplied were not adapted to the needs of the children.” Instead, “he talked about the objects around them,” helping them see their world as a classroom.

Today’s educators might label this culturally responsive pedagogy. But Woodson’s prescriptions ran deeper than the curricula taught in a school. If a school is devised purely as an escape route to a different world, he believed, then it will teach students only the information required to exist in that other world. The students will emerge knowing nothing about their environment except why and how to leave it, leaving them incapable of understanding it, much less improving it.

“Real education,” Woodson wrote, “means to inspire people to live more abundantly, to learn to begin with life as they find it and make it better.” It must help a person to see the surrounding world more clearly, and to find whatever opportunities lie in it for enrichment. “But can you expect teachers to revolutionize the social order for the good of the community?” he asked rhetorically. “Indeed we must expect this very thing. The educational system of a country is worthless unless it accomplishes this task.”

By this definition, Educated is an appropriate title for Tara Westover’s memoir, one of the most dazzling books of 2018. In many ways, Westover’s journey echoed Woodson’s own: a rural upbringing without formal schooling, an unlikely transition to college, and an even unlikelier ascent through some of the world’s premier institutions of higher learning. But while Woodson’s fixation is miseducation, Westover’s is the opposite—a study of what it means to construct one’s own mind.

The marketing of Westover’s book suggested a rags-to-riches tale. In less nuanced hands, it could easily have remained the familiar story of a remote, hardscrabble life, punctuated by misogyny and violence until fate and the indomitable human spirit permit a harrowing escape. That story is certainly there. Westover and several of her siblings were indeed kept out of sight of the government by their anti-statist parents, left to roam their father’s junkyard on a mountaintop in rural Idaho. Her childhood was indeed an atmosphere of constant physical peril, overwhelming paranoia, and isolation. An intensifying pattern of domestic abuse at the hands of her brother did indeed stalk her adolescence and young adulthood.

But Westover chooses instead to take a rarer approach: She narrates the process of learning to see the world around her—both the mountain and the classroom—more clearly. She makes sure her readers witness her mother growing into a successful small-business owner and managing a staff. She summons the stillness and majesty reserved for those who make their lives atop great heights. As her story progresses into the halls of academia, she marvels at the strangeness of that world, too.

Having been deprived of a formal education, Westover seeks to moor herself amid dueling accounts of history. “What a person knows about the past is limited, and will always be limited, to what they are told by others,” she reasons. So, like Woodson, she found herself drawn to the past. “I needed to understand how the great gatekeepers of history had come to terms with their own ignorance and partiality. I thought if I could accept that what they had written was not absolute but was the result of a biased process of conversation and revision, maybe I could reconcile myself with the fact that the history most people agreed upon was not the history I had been taught.”

But Westover comes to realize that even her own history could be revised or contested by others. She becomes attuned, in short, to the possibility of miseducation. Rather than turning inward, however, Westover chooses to broaden her knowledge of the world, believing that “the ability to evaluate many ideas, many histories, many points of view, was at the heart of what it means to self-create.”

Self-knowledge alone does not compose an education; some understanding of the world is necessary. To counter a miseducation, however, requires one more step: learning to recognize one’s inherent traits as gifts, rather than flaws.

My first glimpse of my own miseducation also came in history class, in seventh grade. All my life, I had attended Christian grade schools, led by Protestants, and despite the fact that I was Catholic, it wasn’t until that seventh-grade history class that I began to be taught that my Christianity was deficient. The textbooks we were using came from Bob Jones University, a deeply conservative Christian university in Greenville, South Carolina, which at the time still prohibited its students from engaging in interracial dating. The textbook lingered on the Protestant Reformation, and used a phrase I still vividly recall to describe the Catholic Church, my church, in that era: a tool of Satan.

I started nearly every school day of my life with Protestant Bible classes, Monday through Friday, the only exceptions being field trips or other school occasions. I went to Catholic catechetical classes on Wednesday nights, and Catholic Mass on Sundays. When I saw my church condemned in the harshest tones a Christian book could use, I began to learn a powerful fact: that the Bible could be read in multiple ways, and that I could not trust any person’s reading of it without making my own investigation. I was given a Catechism of the Catholic Church at my confirmation, and I would carry it around with me, so that as my classmates accosted me with questions about why I worshipped Mary or why I ate Jesus, I could look up what the Catholic Church actually believed, and point them to the verses in our King James Bible that those doctrines were built on. I nourished the debate between the Catholic beliefs I had inherited and the Protestant beliefs I was surrounded by, so that from their dispute, I could construct beliefs of my own.

This was a useful lesson to carry beyond Bible class and history class. It colored everything that I was taught. I still don’t remember why it was that my high-school principal, substitute-teaching my geography class for a day when our normal teacher was out, started talking about the Hamitic curse. I imagine we were studying Africa, or perhaps the Middle East, because what other explanation could there be for a teacher to suddenly begin musing on why black people all over the world seemed to have such difficult lives? Some scholars of the Bible, he told us, think that all blacks must be the descendants of Noah’s son Ham, cursed for all his generations by his father for witnessing him in a drunken stupor.

By that time in my miseducation, I’d had enough of my own glimpses of the system that I think I was able not to internalize the lesson. I was black, and I was Catholic, and I did not hate myself for either of those things. But there was one thing I hated in myself, and my miseducators used it to my detriment.

Senior year at my school always began with a class retreat. It was held at a distant, forested event facility that in my memory looks a bit like Cameron Post’s boarding school, God’s Promise. Our school’s headmaster accompanied us, and on the opening night of the trip, we sat in front of a bonfire to hear him deliver a lesson. For those of us moving on to the secular world, he said, senior year would be our final chance to put on the whole armor of God, every day, in front of teachers who could show us how to wear it right.

The world, our headmaster told us, had seduced many Christian men and women before us away from the path of God. And then he sprang the trap. “Some alumni of this school,” he said, “have even fallen into homosexuality.” I don’t know who I hated more at that moment—the headmaster for the reminder that acting on my sexuality was the lowest on a long list of mortal sins, or myself for the growing fear that I could not stop myself from committing it.

I knew well what my Catechism said—what it says to this day—about homosexuality. I had looked up these words more than any other, chasing, perhaps, a futile hope that they would rearrange themselves into some other configuration. Within Christianity, my sexuality made possible one oasis of doctrinal accord between the priests and the Protestants. To quote the Catechism: “Homosexuality refers to relations between men or between women who experience an exclusive or predominant sexual attraction toward persons of the same sex … Its psychological genesis remains largely unexplained. Basing itself on Sacred Scripture, which presents homosexual acts as acts of grave depravity, tradition has always declared that ‘homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered.’ They are contrary to the natural law. They close the sexual act to the gift of life. They do not proceed from a genuine affective and sexual complementarity. Under no circumstances can they be approved.”

This is the secret weapon of miseducation. As Woodson wrote, “When you control a man’s thinking, you do not have to worry about his actions.” For all the distance I had cultivated from my education, for all my skepticism of any one interpretation of the Bible, it took me years before I could hear anything but the words in my Catechism every time my sexuality tried to assert itself.

Even though it began as a religious institution and was named after a clergyman, my high-school teachers thought of Harvard as the very heart of secular society. When our high-school secretary found out I’d be matriculating there, she told me she’d be praying for me. “Thank you,” I said to her, “the classes will be tough.” “It’s so secular,” she replied, as though I hadn’t said a thing.

A year into college, the spell of my miseducation had worn off enough that I found myself taking courses on the Bible again—multiple ones, even though I had rarely experienced a day of schooling from first through 12th grade that didn’t begin with a lesson on that book. My most treasured Bible lessons didn’t come from my professors, but from our college chaplain, who gave Sunday lectures in Memorial Church, the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals, the legendary Peter J. Gomes. His very existence as a man like me—Christian like me, black like me, gay like me—leading moral and religious instruction at an institution like Harvard, was manna to me.

The way Gomes taught the Bible was a revelation. In his lessons, I saw the book as though for the first time. In high school, I had spent an entire semester of Bible class in a line-by-line reading of the book of Genesis. Yet over the years, I came to understand that I had never truly learned the lesson of the creation story that begins the book. “Its first moral tale,” as Gomes put it in The Good Book, his published collection of essays about the Bible, “is not about sex or even about disobedience. We might say that it is about a false trust in the benevolence of knowledge.” Gomes knew that a school can be a curse.

When Eve and Adam eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, they learn to be ashamed of their very bodies. They become so disgusted with their nakedness that they have to hide themselves from God. The terrible cost of this lesson, of learning to hate oneself, is the invention of sin, the root of all the evils in the world. In the Bible, Jesus arrives to redeem us from this lesson, bearing two great commandments, the second of which is this: Love thy neighbor as thyself. There is a precondition embedded in that commandment that all my years of Bible schooling never taught me: To follow it, one has to love oneself. A lesson so simple, it’s nearly impossible to teach.

It’s important to remember that a school can be a gift.

In 1889, a wealthy, white Catholic heiress named Catherine Mary Drexel felt a calling from God to dedicate her life and fortune to the uplift of black and Native Americans. She became a nun, taking the name of Sister Mary Katharine Drexel. During two years at a Pittsburgh novitiate, she learned how to lead a religious order. At the time, while many American orders worked in Native and African American communities, Drexel came to be convinced of the need for a new order exclusively dedicated to that purpose. And so in 1891, Mother Katharine Drexel founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People.

Drexel spent years working on reservations and in black communities throughout the United States, founding and supporting missions and schools across the country with her annual income from her family’s estate. She witnessed the pitfalls that could attend religious charity, especially in communities of color, and she tried carefully to avoid them.

Building schools for people of color was dangerous work. In Beaumont, Texas, for example, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament had to face down threats from the Ku Klux Klan. “We will not stand by while white priests consort with nigger wenches in the face of our families,” read the signs posted by the Klan outside the order’s church. “If people continue to come to this church, we will dynamite it.” But Mother Katharine and her sisters persisted in the face of these threats, creating missions from Washington, D.C., to St. Louis, Missouri, and beyond. When a bishop in Nashville, Tennessee, asked her to open a school for black Catholics in his city, Drexel agreed to open a school, but not just for Catholics. “Katharine Drexel stressed to him that her mission was to Indians and colored people, regardless of their religion, and that if he wanted her to open a school for black children in his diocese, it would have to be a school open to those of all religions,” Cheryl D. Hughes wrote in her biography of Drexel.

As Mother Katharine’s order grew, a need emerged for black teachers. And so Drexel and her sisters created a teachers college, in New Orleans. At the time, few women had college degrees, and many teachers didn’t. Katharine Drexel’s Xavier University, founded in 1925, was quietly revolutionary. “At a time when official Church teaching prescribed separate sex institutions for men and women, Xavier University was coeducational,” Hughes wrote. “While Xavier was indeed a Catholic coeducational university, it was never exclusively Catholic. Students of all faiths, or no faith, were accepted to Xavier.”

“The influence of Katharine Drexel and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament through Xavier University cannot be overstated,” Hughes wrote. “In 1987, 40 percent of the New Orleans public school teachers were Xavier graduates.” In 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized the late Katharine Drexel as a saint.

Xavier’s influence grew mightily during the tenure of Norman Francis. Francis, the first layperson and African American to lead the university, had grown up in a poor family in Lafayette, Louisiana, and attended Xavier as an undergraduate. He’d gone on to become the first black student admitted to Loyola University’s law school. He was drafted into the Army, and after he completed his military service in 1957, he received the call to be dean of men at Xavier.

In 1961, when the Freedom Riders needed refuge from white segregationists firebombing their buses, Dean Francis housed them at Xavier. He was appointed president of the university by the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in 1968, and would go on to become the longest-serving college president in the nation. After Hurricane Katrina battered New Orleans in late August 2005, Francis assembled his staff and announced that the university would reopen in five short months. “We came back on January 17,” he told Anitra Brown of The New Orleans Tribune. “We had 75 percent of the student body. We lost freshmen, but every class graduated on time—including the class of 2006, whose commencement speaker was a young U.S. senator from Illinois named Barack Obama.”

In 2015, the reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones went to New Orleans to profile Xavier for The New York Times Magazine. She described the pitfalls many black students face in college pre-med programs, and the system Xavier set up to avoid those pitfalls. Thanks to that level of care, Hannah-Jones wrote, Xavier “consistently produces more black students who apply to and then graduate from medical school than any other institution in the country. More than big state schools like Michigan or Florida. More than elite Ivies like Harvard and Yale. Xavier is also first in the nation in graduating black students with bachelor’s degrees in biology and physics. It is among the top four institutions graduating black pharmacists. It is third in the nation in black graduates who go on to earn doctorates in science and engineering.”

A school can be a gift.

July 2018 marked the beginning of the first semester at Akron’s I Promise public school, funded in part by a gift from the NBA legend LeBron James. The school builds on James’s years of philanthropy in his hometown of Akron, including a partnership with the University of Akron to cover tuition costs for some low-income students in the city. He offered free GED classes and tests to the parents of students in his programs, with a free laptop awaiting every parent who passed the class.

When he was in the eighth grade, the enormity of James’s athletic talent meant he had the pick of high schools in Akron. As his memoir tells it, James and his three friends decided to attend St. Vincent–St. Mary High School, a private school, because of a pact the four friends made to stay together, instead of the public school Buchtel, a launching pad for many of the city’s black athletes. “To many in Akron’s black community,” the memoir says, the choice to attend a mostly white Catholic school meant “we were now traitors who had sold out to the white establishment.”

That history heightens the significance of James’s gift to Akron Public Schools. Like the schools James attended from kindergarten to eighth grade, I Promise is a traditional district public school. Most of the money to create and support the school comes from Akron Public Schools. The grant from James covers some of the school’s start-up costs, but ultimately, James’s foundation will largely be supporting the lives and needs of students and their families beyond the classroom, securing them clothing, food, counseling, transportation, and full-ride scholarships to the University of Akron, while helping their parents earn GEDs, find work, and manage money. According to a five-year master plan obtained by The Atlantic, the I Promise school’s “homegrown” curriculum aims to pull students more fully into the world around them, immersing them in Akron’s “businesses, neighborhoods, organizations, history, and issues.”

“When people ask me why, why a school, that’s part of the reason why—because I know exactly what these 240 kids are going through,” James said to the crowd assembled for the school’s opening day. “I know the streets they walk. I know the trials and tribulations that they go through. I know the ups, the downs. I know everything that they dream about. I know all the nightmares that they have. Because I’ve been there. I know exactly what they’re going through. So they’re the reason why this school is here today.”

Will the I Promise School succeed? There are so many ways it can fail. Woodson’s book was written 85 years ago, yet so many of its cautions still pertain: Akron’s very hopes for the school could curse it. It could become more a symbol than a school, a formula for an ever-imminent “national model.” It could thrive, and become a cudgel against every school that lacks its advantages. The students could become objects of America’s twisted politics, victims of the enmity of a callous president toward their benefactor.

“Philosophers have long conceded,” Woodson wrote, “that every man has two educations: ‘that which is given to him, and the other that which he gives himself. Of the two kinds, the latter is by far the more desirable.’” So to those who imagine themselves as educators, he argued, what is needed is not leadership, but service. The “highly educated Negro” who would educate others of his race, Woodson said, must “fall in love with his own people, and begin to sacrifice for their uplift.” The purpose of a school, in other words, must be to help its students learn to appreciate the gifts within themselves, and discover how to help others with those gifts.

“If you understood who you are,” Ras Baraka once said, “you would understand that the world belongs to you. And you shouldn’t claim a piece of it, you should claim all of it. And when you begin to claim all of it, you fight for the whole of humanity. And when you fight for the whole of humanity, you help us become freer. And you begin to, in essence, change your immediate condition.”

That, in miniature, is the process of education: to love oneself enough to recognize in one’s own need an opportunity to serve another. To view the world with enough empathy and distance to see struggle that overlaps with one’s own, whether on a mountaintop junkyard in Idaho, a neighborhood in Akron, or a recording studio in New Jersey. To find the tools to ease that struggle, and wield them, at last, to change the world.

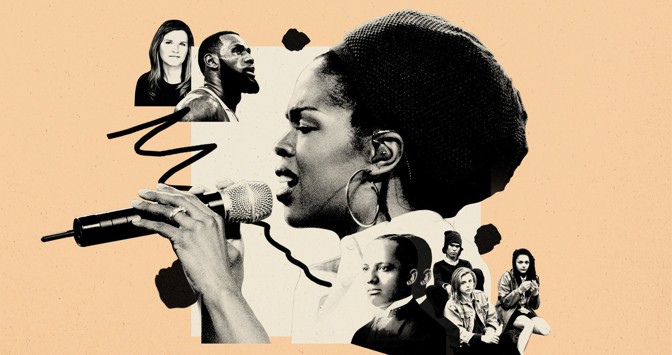

* Photo-collage images courtesy of Chris Lopez / Sony Music Archive / Getty / Marcio Jose Sanchez / AP / Filmrise / Penguin Books / Paul Stuart

If you have ever turned on your television on New Year’s Eve and felt even a little bit jealous of the partyers gathered in Times Square to watch the ball drop, I want you to remember one thing: A lot of those people are wearing diapers.

It has been widely reported that there is nowhere for New Year’s Eve revelers to use the bathroom in Times Square—no porta-potties, and don’t even think about trying to pop into the Disney Store and asking to use its restroom. So people urinate in the street, hold their kids over railings while they pee, dehydrate themselves all day, and wear adult diapers. Or multiple maxi pads, as one woman told Gothamist in 2015.

There’s a saying that how you spend New Year’s Eve is how you’re going to spend the rest of the year, which is patently ridiculous if taken literally, but even taken figuratively, spending New Year’s Eve soaking in your own urine, hip to hip with millions of other people, illuminated by the bright lights of 20-story ads for light beer or whatever, is a bit of an inauspicious start to the year.

And if Times Square is the top of the dial of New Year’s Eve unpleasantness, discomfort cranked up to 10, then the average experience of going out on December 31 is still likely a 5 or 6.

Standing in line for a bar has never been worth it, not once in the history of time. A really quick line to check IDs at the door is permissible, but that’s it. A stationary line extending down the sidewalk means the place is so packed that when you get to the front, the bouncer has to assess whether or not he can realistically shove one more sardine into that can. And once you make it in, you can expect to spend the night swimming upstream of a riptide of bodies to get to the bar, the bathroom, back to your friends, anywhere. If a night of shifting foot to foot in the 12 square inches of floor space you’ve carved for yourself sounds like fun, then going out on New Year’s Eve is going to deliver just the experience you were hoping for.

You will likely have to pay for the privilege, though. According to Ashley Bray, the editor of Bar Business Magazine, a trade publication for bars and nightclubs, most bars sell tickets for New Year’s Eve, even if they don’t usually charge a cover. Many will host a special event of some kind, with food, or a DJ, or a champagne toast, and it makes sense for bar owners to want an advance head count. But for the goer-outer, that means if you were hoping to stop by your favorite local bar on New Year’s Eve, there will be a price just to get in the door.

Those who would brave the cold on New Year’s Eve are likely well aware of these obstacles—I don’t think I’m exactly blowing the lid off anything here (but if you didn’t know about the diapers … now you know). It may be that some truly enjoy the experience of going out on December 31, and if so, Godspeed to you and drive safely. But I think it’s fair to say that New Year’s Eve is few people’s favorite holiday. Several tongue-in-cheek “holiday ranking” articles place it solidly in the middle of the pack, a survey by FiveThirtyEight ranked it fourth, and Conor Friedersdorf once railed against it in the esteemed pages of this very website. “A too expensive exercise in affected frenzy and anticlimax,” he called it.

And he’s right—but it doesn’t have to be. Both the frenzy and the anticlimax can be avoided by simply staying in. I genuinely look forward to New Year’s Eve every year, and that’s because my two best friends and I have designated it Our Holiday, and we always spend it together. The form of our celebration fluctuates—sometimes we dress up and cook ourselves a nice meal, sometimes we watch horrible-yet-incredible made-for-TV movies, and sometimes we hang out with my friend’s family and play a game of Celebrity. It’s always chill, never frenzied, and it can’t possibly be anticlimactic because the only expectation I’m placing on the evening is to spend some quality time with my closest friends.

The cultural pressure to go out on New Year’s Eve, or to strap on a diaper so you can see the ball drop in person, or to make the evening into an Event in some other way, stems from the undue weight society gives to a year’s end. It’s supposed to be a finale, followed by a fresh start. And as anyone who’s watched enough TV shows would know, they save all the juicy stuff for the finale. The revelations, the big party scenes, the long-awaited kiss between the romantic leads. So if you want your year to have a good finale, you’d better learn a big lesson, take yourself out to a party, and have someone to kiss at midnight. (The origins of the midnight New Year’s kiss tradition are murky, but it certainly seems that When Harry Met Sally poured fuel on its fire.)

“New Year’s Eve is a date that people usually remember,” says Gabriele Oettingen, a psychology professor at New York University and the author of Rethinking Positive Thinking. “People take it seriously, to conclude and to begin. And sometimes you don’t want to be alone, because you want to share in this kind of ending and be together with other people when you start over. So people seek company probably more than on any other normal day.

“The question really is,” she continues, “what company do you seek?” She suggests trying to divorce what you really want to do from what you feel expected to do, imagining how you would feel if you spent New Year’s Eve as you wished, identifying obstacles in the way—whether that’s FOMO or peer pressure or anything else—and then making a concrete plan for the holiday. This is a strategy she’s researched extensively called WOOP, which stands for “wish, outcome, obstacles, plan.”

It might seem a little silly to do a whole visualization technique just to figure out how to spend New Year’s Eve, but it’s worth asking yourself whether you’re making a to-do out of this particular rotation of the Earth just because you think you’ll feel guilty if you don’t. “It’s difficult to really do what you want to do and not to do what you don’t want to do,” Oettingen says. So this year, when the ball drops on New Year’s Rockin’ Eve with Ryan Seacrest and whoever else, spare a thought for those people wearing diapers in Times Square who might really, in their heart of hearts, rather be somewhere else.

The economy can only go down from here. The number of revelations from Robert Mueller can only go up.

But that doesn’t mean a Democratic candidate is a shoo-in for 2020—everyone thought Donald Trump faced too many hurdles to win in the first place, too. The Democrats who are about to launch presidential campaigns can tell themselves Trump looks weak now, but this could be just the midpoint in his reordering of American politics in his image.

Before any Democrats can get to Trump, though, they’ll have to get through the “Why not me?” primary—the next 14 months of scramble and mania, set against a primary-calendar shake-up that for the first time has delegate-heavy California and Texas both voting at the beginning of March, which will make it so candidates have to campaign for those millions of much more diverse votes in order to have a chance of locking up the nomination. The only thing that’s clear so far: The early polls being circulated will likely have as much relevance to the outcome of the race as learning Mandarin does to visiting Algeria.

Within weeks from now, the 2020 Democratic-primary race will be at full force. Here are 10 factors that will define it—and make it unlike any that have come before.

The pundit president